Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.15 Vanderbijlpark Jul. 2016

HANDS-ON ARTICLES

A systematic method for dealing with source-based questions

Simon Haw

Retired History subject advisor of the KwaZulu-Natal Education Department simonhaw@telkomsa.net

ABSTRACT

This article is intended to help both learners and teachers get to grip with the source material used in examination and tests by providing a systematic way in which to analyse them for such factors as usefulness, reliability and validity. The various factors inherent in source analysis are arranged into a table, called the source matrix. To help learners and teachers further two examples are given of how the matrix could be used to analyse the source material provided. While such detailed analysis will never be required in tests and examination, it should nevertheless prevent the sort of meaningless answers which currently appear in many tests and examinations.

Keywords: Sources; Analysis, Usefulness; Reliability; Provenance; Validity; Bias; Typicality; Relevance

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to work towards a systematic approach to answering some of the more complex source-based questions which you might come across in examinations and tests. For instance, if you are asked about the usefulness of a source or perhaps asked to compare two different sources using usefulness as a criterion, what should you be looking for? Other criteria that will be also handled in this article are: relevance, reliability and bias.

Some general remarks about sources

Sources take many different forms: from artefacts (objects made by humans e.g. clothing, medicines, vehicles etc.), visual sources such as paintings and photographs, to documents which run the whole gamut from various forms of published sources such as government reports or newspapers to unpublished sources such as private letters, diaries etc.

The focus of this article will tend to fall most strongly on documentary sources, although the criteria are applicable to all forms of sources. Sources fall into the categories of primary, secondary and tertiary. Primary sources are those produced by individuals or groups directly involved in the events being studied. However, it is not always easy to determine the degree to which something is a first-hand account so treat documents like contemporary newspaper accounts as primary sources. Secondary sources are usually the products of historians, journalists, students or writers who make use of the available primary sources as well as secondary sources to construct a view of the historical event or period they are dealing with. The book entitled The Concentration Camps of the Anglo-Boer War A Social History by Elizabeth van Heyningen (2013) is a secondary source. Tertiary sources are usually broad surveys which rely almost entirely on secondary sources. The Collins History of the World in the twentieth century by JAS Grenville (1994) is an example of a tertiary source.

Sources contain two important elements, namely facts and opinions. Although obviously important to historians, facts, provided they are accurate and/or not startlingly new, are less interesting to historians than opinions, because it is here that one can get a sense of what different individuals or groups thought about the events that were taking place around them. They also provide important clues as to what motivated a person or people to act in a certain way. Interestingly, even the most factual of sources in a sense contains an element of opinion as the person who produced the source has to decide which facts are important enough to be included and which should be left out, and a whole range of interesting factors often lie behind these decisions.

Using the Source Matrix

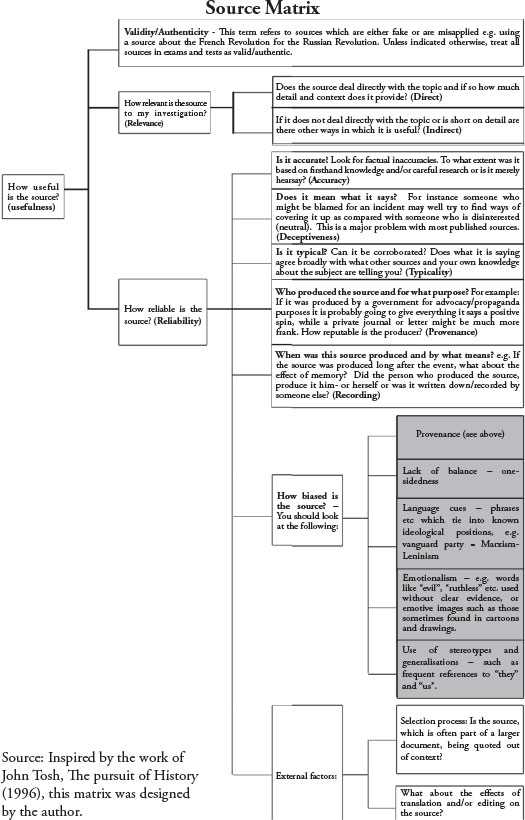

On the next page appears the Source Matrix, which it is hoped will give you a systematic way of approaching sources. Basically it works like this:

• If you are asked about the usefulness of a source for a certain task, what should you look at? The matrix suggests that you should look at three factors: validity, relevance and reliability and it provides you with the questions you should ask to evaluate these factors.

• If you are asked about the reliability of a source for a certain task what should you look at? Once again the matrix provides you with specific questions to ask about the source to reach a reasoned judgement. The same is true of bias, which is treated as a sub-section of reliability.

Have a good look at the Source Matrix and then we will use it to examine specific examples of sources to show you how it works.

The application of the Source Matrix

Now that you have had a chance to look at the Source Matrix, let's apply it to some concrete examples. Our first example applies to a source on the Cold War.

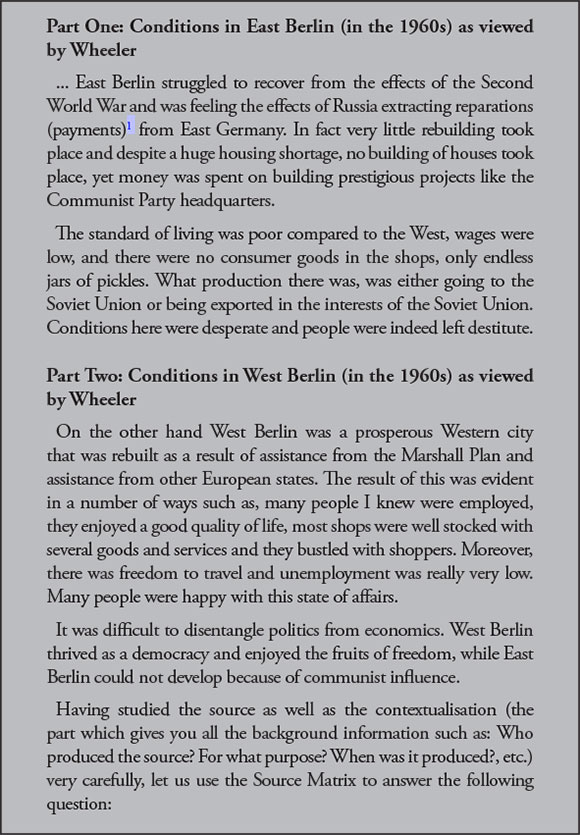

The Key Question is: What factors led to the building of the Berlin Wall?

The source we are using was used in the November 2008, Paper 1. However, it was never properly contextualised in this paper. We were told only that it resulted from an interview of Charles Wheeler, a West Berlin citizen, and that it appeared on the website: www.gwu.edu/nsarchiv/coldwar/interviews (Do not try and use this link as it will not work in its present form, although the site still exists). This really did not supply enough information for those writing the exam to make informed judgments on the source. The contextualisation actually provides wrong information as it says that Wheeler was commenting on Berlin in the 1960s when in fact he was talking about Berlin in the early 1950s at the time of the Berlin Riots. Here then is the full background to this source:

The document comes from the National Security Archives at the George Washington University. This independent archives and research institution was set up in 1985 to make available and study declassified American documents relating to events such as the Cold War. The Wheeler interview was part of a project to document the Cold War by means of oral history interviews with individuals who were involved in various ways. Wheeler was the BBC's German correspondent based in West Berlin in the early 1950s. The interview was made with Wheeler in May 1996. The main focus of the interview of which only a small part is reproduced in the source was the Berlin Riots of 1953. An important point that Wheeler makes in an earlier part of the interview is that, as a foreign correspondent, he was not allowed to visit East Berlin.

Having given you the background here is the source that consits of two parts:

How useful would this source be for a historian studying the factors which led to the building of the Berlin Wall?

Validity - As you will see from the matrix, the examiners are not likely to give you a bogus source, although, as we have seen, they may contextualise it wrongly, so you do not need to concern yourself with this particular aspect of source criticism. In fact in this particular case, because Charlie Wheeler is describing the situation in the early 1950s, this source is invalid for the 1960s.

Relevance - This source would receive a fairly high score on this criterion because, although it does not deal directly with the Berlin Wall, it certainly gives insight into the factors which may have contributed to its building, which is the main focus of the question you have been asked.

However, it should be borne in mind that Wheeler is commenting on the situation in East and West Berlin in 1953 - there were almost certainly some changes between 1953 and the building of the Wall in 1961. One of the changes was that the Soviet Union was no longer directly involved in the running of its East German satellite. This is clearly shown by the fact that Stalin's Soviet Union was directly involved in imposing the blockade in 1948 but had no direct involvement in the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961, which was erected by the East German government of Walter Ulbricht.

This was very convenient for Khrushchev as, even though the Wall broke several treaty terms, he could claim that the Soviet Union had nothing to do with it, although there is evidence that he suggested the idea to Ulbricht.

Reliability - The following factors should all be taken into account when judging reliability:

Accuracy: There is no evidence of any wrong facts and as the BBC correspondent in West Berlin Wheeler's business would have been finding out as much as he could about the situation.

However, we know from reading the contextualisation that Wheeler, as a foreign correspondent, was not allowed to enter East Berlin. This means that his information on conditions in that part of the city would have had to come mainly from Germans who either worked in West Berlin but lived in East Berlin or refugees who had fled from the Eastern sector. The likelihood would therefore be that most of his sources would view developments in East Berlin in a negative light.

Deceptiveness: As this interview occurred after the conclusion of the Cold War, there would be no reason for Charlie Wheeler to be deceptive in any way. In other words the source means what it says.

Typicality: As learners, the only way we can test whether this source is typical is to compare it with the other sources we have been given in the exercise and with our own knowledge. Judged in this way, it appears to present a similar and therefore typical view of the situation in the two Berlins found in most other sources. In other words the other sources available to us appear to corroborate (agree with) what is being said in this source.

Provenance and Purpose: The main things we can say about provenance is that Charlie Wheeler was English; he was working for the BBC and was living in West Berlin. His access to East Berlin would therefore have been nonexistent and he is likely to have approached the situation from the perspective of a supporter of the West. These are indeed factors which might affect the reliability of what he is saying. However, as this was not a propaganda piece, and was recorded after the Cold War had ended, there is no evidence that he has made any deliberate attempt to distort the information he provides. Furthermore, both the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and the George Washington University can be regarded as reputable sources with high standards of scholarship.

Recording constraints: In this case Wheeler is being interviewed about events which had taken place 44 years earlier. Unless he kept a journal to which he was referring, of which there is no evidence in the transcript of the interview, distortions may have crept in because of the long period involved. Memory even in the short term can be the cause of considerable distortion.

Furthermore, this testimony was obtained using an oral history interview technique; this might further confound the reliability of the testimony. On the other hand as a seasoned journalist his job would probably have made him a more careful observer than someone in a different line of work.

Bias: Although this is certainly written from the perspective of a supporter of the West - a factor which needs to be kept in mind - it does not exhibit particularly strong signs of bias. Let's quickly look at the various bias indicators:

• Provenance and purpose: See above.

• Lack of balance: Although he states that conditions in West Berlin were much better than those in East Berlin, he does provide the political context for these differing situations. Soviet Union extracting reparations versus the Marshall Plan and deliberate Western reconstruction.

• Language cues: There are some signs of anti-communism but not very strongly expressed.

• Emotionalism: The language appears balanced and is not very emotional. Look for lots of adjectives such as evil East German government, enlightened Western powers etc.

• Use of stereotypes and generalisations: Only to a limited degree. There is some attempt to qualify statements such as "Many people were happy with this state of affairs" rather than "Everybody was happy with this state of affairs".

External factors: A significant distorting factor is that this is a very short extract from a reasonably long interview. However, more importantly the original contextualisation as supplied to candidates in the November 2008 examination suggests that this interview was recorded at the time of the events being described and that it provides a view of conditions in the 1960s, when in fact it dealt exclusively with the 1953 Berlin Riots - the period immediately after the death of Stalin. These points regarding other distorting factors, however, would not feature in your answer as they have not been provided to you in the original contextualisation of the source.

• As you can see from the foregoing, you could spend hundreds of words just deciding the degree of usefulness of a source. So how would you go about answering the original question about the usefulness of this source for understanding factors leading to the building of the Berlin Wall? We suggest that your answer should contain the following points:

• The source provides useful details about the different lifestyles in West and East Berlin (relevance).

• It is worth noting that Wheeler was talking about the situation in Berlin in 1953, while the focus in the question is on 1961 - much can change in eight years (relevance).

• The descriptions of lifestyles in the two Berlins are supported by other sources and by my own knowledge (accuracy, deceptiveness, typicality).

• A degree of bias needs to be taken into account as the author was a BBC correspondent living in West Berlin, who was not allowed access to East Berlin (provenance).

• However, as this was recorded after the Cold War, no ideological purpose would be served by giving a strongly biased account.

• Further cautions are that this source is based on oral testimony taken 44 years after the event - memory lapses/distortions should be kept in mind.

If you are asked about how reliable you think this source is, you would leave out the first two bullets concerning relevance - all the others would apply, however.

Let us look at a source which contrasts very strongly with the first source. The following source is the front page story which appeared in Die Vaderland (The Fatherland), a Johannesburg-based Afrikaans language newspaper, the day after the Women's March on August 9, 1956. As was the case with virtually all mainstream Afrikaans-language papers, Die Vaderland was strongly in favour of the National Party government that had come to power in 1948.

Key Question: What happened during the Women's March of 1956?

The question is: How useful would the following source be for someone trying to find out what happened during the Women's March of 1956?

Translated out of the Afrikaans the main headline and front page article reads as follow:

Do their Parents know where they are?

It is very clear that these white children in the photos do not know what is happening.

Do their parents know that they were taken by their non-white oppassers (child minders) to the demonstration at the Union Buildings?

When we took this photograph the little boy was very close to tears. The non-white on the right of the photo took off her shoe and gave it to him to comfort him as shown in the photograph.

Validity: The source is valid.

Relevance: The report contains no details as to who was involved, how many were involved, what their demands were, what happened on the day of the march. Therefore for the particular question being asked it is almost entirely irrelevant.

Reliability

Accuracy: It is not an accurate account of what happened during the Women's Day March as it focuses on the irresponsibility of the black minders in having taken their young white charges to such an event to the complete exclusion of everything else. It therefore gives a distorted impression of the March.

Deceptiveness: This is slightly tricky in that the writer of this article definitely meant what he says. However, the article deceives the reader as to the true nature of the Women's March.

Typicality: This newspaper article is not at all typical of accounts of the Women's March. All the other accounts focus on who was there, how many were there, and what happened. Well-disposed mainstream papers like the Rand Daily Mail emphasised the impressive discipline shown by the women.

Provenance: This source is taken from a newspaper, which is a strong supporter of the apartheid government. The purpose of the writer would tend therefore to be to belittle any opposition to government policy and support government policy very strongly.

Recording: This is a contemporary, primary source. It was produced by journalists sent to cover the Women's March for the paper. Consequently there are unlikely to be any problems related to memory distortions over time.

Bias: This is a very biased source. Let us look at why this is the case:

• Provenance :See above

• Lack of balance / one-sidedness: The reporter picks out one or two instances where white children were present at the March and tries to blow this up into a major feature of the March. Furthermore the evidence he or she advances for what he or she is saying is very weak. For instance, we do not know whether the minders had permission to take the children to the Union Buildings or not, and we have to rely on the journalist that the little boy was upset as this is not obvious from the photograph.

• Language cues: Nothing much to comment on in the case of language.

• Emotionalism: This appears to be very strong. The image of "poor little white children" being exposed to danger by the people who are looking after them is calculated to tug at the heartstrings of the readers. This idea is emphasised by the notion that the little white boy was near to tears.

• Stereotypes and generalisation: Strong stereotyping of black women as ignorant, irresponsible servants. A degree of generalisation - as one is meant to assume that this sort of "irresponsible" behaviour was widespread.

External Factors: The fact that the article has been translated from the original Afrikaans may be a distorting factor. However, the original has been published alongside the translation.

So how might you answer a question about the usefulness of this source to someone trying to find out what happened during the Women's March. Here are some of the main points which should be in your answer:

• Relevance is very low as the source contains no details about the Women's March other than that there were a few white children there, apparently with their minders.

• The source gives such a narrow view of the event that it can be described as inaccurate and not typical (in other words the information it gives is not supported by other sources and seems to focus on one detail of the gathering that was not typical of the March as a whole).

• The source was produced by a journalist working for an Afrikaans-language, National party newspaper which strongly supported apartheid and white domination (Provenance).

• Because of the provenance, the source is very biased. This is shown by such things as the emotional tone of the source and by the use of stereotypes.

A question asking about reliability would focus on the last three points.

Note that if the question had been about the attitude of National Party supporters or the National Party press to the Women's March, this source would have been both more useful and more reliable. This shows that a lot of the characteristics of sources discussed in this guide depend on the particular question which is being asked (context).

All the foregoing is about answering source-based questions, but the points made in this connection have strong implications for examiners setting these types of questions and/or for moderators and others assessing whether the question is a good question or not.

The following points can be deduced from what has been said about answering these types of questions:

• Wherever possible use primary sources rather than secondary ones.

• If secondary sources are used, they must be thoroughly referenced giving such details as author, publisher, place of publication and date and, where relevant, specific details about the author. This will prevent the use of extracts from David Irving's book without reference to the extremely controversial nature of his views.

• Very careful consideration needs to be given to the language level in sources. Try to choose sources which are written in accessible English with due consideration given to the fact that these sources are going to have to be translated.

• Thorough contextualisation is of enormous importance in the case of primary sources as is clearly demonstrated by the first example used in this paper. Without this contextualisation it will be difficult, if not impossible for the candidate to make any meaningful comments about factors such as usefulness and reliability.

• The category "usefulness" was created largely because the usefulness of a source is not always readily apparent. Since the post-modern stress on textual analysis, there has been as much concentration on the unintended significance of sources as there has been on what the person who produced the source intended to say. Marc Bloch, one of the founders of the Annales school of History refers to this as "the evidence of witnesses in spite of themselves" (as cited in Tosh,2015:75)and regards these unwitting revelations as being of great significance to the historian.

• Wherever possible, the question should be unambiguous in its phrasing and there should be a clear answer so that examiners are not forced to fall back on the "any other response" type of entry in the marking memorandum.

• It needs to be clearly acknowledged that full source analysis is beyond the scope and competence of the vast majority of learners. Furthermore, most teachers have not had the training to make them confident practitioners in this field. It is important therefore, that our ambitions are scaled down to accord with the reality of the situation. As teachers of History, we would like to get across to our learners the fact that sources can almost never be taken at face value. It is this critical stance towards information and opinions which makes History so valuable in creating the sort of critical thinkers which a modern democracy requires.

• At present, too much of the questioning in History amounts to little more than comprehending the sources provided.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article has been to provide a systematic way of analysing a source in terms of factors such as reliability, bias, usefulness and validity. This should assist both the candidate writing a test or examination and the teacher setting the questions to arrive at meaningful questions and answers. Clearly the sort of exam question where virtually any answer, including the most vague and generalised, is regarded as acceptable has little educational purpose and hopefully this article will contribute to preventing this unfortunate tendency.

References

Ellis, P, Haw, S, Karumbidza, B, Macallister, P, Middlebrook, T, Olivier, P & Rogers, A 2012. History learner's book. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter. [ Links ]

Grenville, JAS 1994. Collins history ofthe word in the twentieth century. London: HarperCollins. [ Links ]

Tosh, J 1996. The pursuit of history. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Tosh, J 2015. The pursuit of history: Aims, methods and new directions in the study of history (6). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Van Heyningen, E 2013. The concentration camps of the Anglo Boer War: A social history. Johannesburg and Cape Town: Jacana Media. [ Links ]

1 The bracketed phrases appeared in the 2008 History paper.