Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.14 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2015/nl4a5

ARTICLES

The role of history textbooks in promoting historical thinking in South African classrooms

Daniel RamorokaI; Alta EngelbrechtII

IFaculty of Education, Humanities Education University of Pretoria Ramoroka.d@dbe.gov.za

IIFaculty of Education, Humanities Education University of Pretoria Alta.Engelbrecht@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article focuses on the analysis of three textbooks that are based on the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS), a revised curriculum from the National Curriculum Statement which was implemented in 2008. The article uses one element of a historical thinking framework, the analysis of primary sources, to evaluate the textbooks. In the analysis of primary sources the three heuristics distilled by Wineburg (2001) such as sourcing, corroborating and contextualizing are used to evaluate the utilisation of the primary sources in the three textbooks. According to the findings of this article, the writing of the three textbooks is still framed in an outdated mode of textbooks' writing in a dominant narrative style, influenced by Ranke's scientific paradigm or realism. The three textbooks have many primary sources that are poorly contextualized and which inhibit the implementation of sourcing, corroborating and contextualizing heuristics. Although, some primary sources are contextualized, source-based questions are not reflecting most of the elements of sourcing, corroborating and contextualizing heuristics. Instead, they are mostly focused on the information on the source which is influenced by the authors' conventional epistemological beliefs about school history as a compendium of facts. This poor contextualization of sources impacted negatively on the analysis of primary sources by learners as part and parcel of "doing history" in the classroom.

Keywords: Sourcing; Corroboration; Contextualisation; Realism; Epistemological belief; "Doing History"

Introduction

This article articulates a source-based approach in the writing of textbooks in South Africa and evaluates the extent to which textbooks reflect one of the critical elements of historical thinking and the notion of "doing history" which is in keeping with the knowledge construction pedagogical approach advocated by social and cultural constructivists. "Doing history" in history classrooms implies a teaching strategy that enables the teachers and learners to reflect on the sophisticated knowledge of the discipline. According to White, one of the literary theorists, history can be used to provide the theoretical arguments that justify the instrumentalisation of historical memory by nationalist elites in their sometimes genocidal struggles with their opponents (Cited in Moses, 2005:311). The historians such as White, Nietzsche and Seixas (Stearns, Seixas & Wineburg, 2000; Cited in Moses, 2005:11) have accommodated the need for collective memory or best stories of the nation but have also cautioned against the abuse of history to alienate other nationalities. In South Africa it is critical that curriculum developers and textbook writers should keep the balance between the "best story" which is the "road to democracy" and elements of historical thinking such as the analysis of primary sources. It is therefore necessary for the learners to be engaged in the cognitive analysis of sources in order to ascertain facts about the past and to establish what actually happened. This article focuses on the analysis of primary sources and uses the three heuristics, "sourcing", "corroborating" and "contextualising" in order to evaluate the authenticity and trustworthiness of sources as historical sources. The article also utilises the three heuristics to evaluate the variety of sources and source-based questions on these three textbooks to ascertain whether questions posed require learners to analyse sources by the reflecting on the elements of historical knowledge construction such as "sourcing", "corroborating" and "contextualising" (Wineburg, 2001; Seixas & Morton, 2013).

Research problem

Textbooks writers in South Africa are in a dilemma: they should reflect the "best story" of the struggle such as the road to democracy and the role played by the ruling party in the struggle against apartheid and yet they are expected to reflect elements of historical thinking such as analysis of primary sources and other disciplinary skills. In addition, if they focus on the activities that relate to knowledge construction, they would be delaying learners because the examination question papers are assessing the superficial knowledge of the sources and compromise critical aspects of sources such as the sourcing heuristics (Standardised National Question Paper, 2014). Therefore, the struggle of teaching historical thinking would be won, if textbook writers strike a balance between prescribed content and historical thinking or "doing history". The analysis of primary sources to reflect historical thinking or the notion of "doing history" is critical because according to Seixas and Morton (2013), primary sources are the raw materials for the construction of historical knowledge and therefore it is necessary that textbooks provide learners with the opportunity of the reading and analysing of primary sources.

Research question

The question driving this article is as follows: To what extent are prescribed text books reflecting elements of historical thinking such as the analysis of primary sources? The formulation of this question is encouraged by the call by history education experts (Wineburg, 2001; Morton & Seixas, 2013) who prioritised the use of primary sources in the teaching of history. The shift from the transmission model of teaching to construction of historical knowledge in the classroom was influenced by the new learning theorists by the socio-cultural constructivists who considered the transmission model as inadequate in the teaching of the elements of historical thinking (Gallimore & Tharp, 1988; Bain, 2008). The construction of the theoretical framework to analyse sources was encouraged by the new learning theory which inspires historians to ensure that learners and teachers reflect the sophisticated knowledge of the discipline in the class rather than regurgitate the narrative constructed by historians (Morton & Seixas, 2013).

Methodology

The qualitative paradigm is epitomised by the interpretive strand to research and focuses on understanding, interpretation, and social meaning. This is considered an appropriate design for this research. Thematic analysis has been used for the encoding of qualitative information (Boyatzis,1998) and a conceptual framework of historical thinking has been used to analyse data which would be based on the analysis of three prescribed textbooks. Three main textbooks that are prescribed and that comply with the requirement of CAPS have been selected for this study. The following textbooks were analysed, namely Via Africa History Grade 12 (Grove, Manenzhe, Proctor, Vale & Weldon, 2013) and Focus History Grade 12 (Fernandez, Wills, Mc-Mahon, Pienaar, Seleti & Jacobs, 2013), Spot On History Grade 12 (Dugmore, Friedman, Minter & Nicol, 2013).

Wineburg (2001), an educational psychologist and historian, has contributed immensely to developing a framework for engaging young learners in the cognitive process of analysing sources. He, along with other experts such as Seixas and Morton (2013) and Reisman (2012), advocate the use of primary sources in the classroom in order to engage learners in the sophisticated process of producing historical knowledge. In responding to this new approach, Wineburg (1999) identifies in historians an epistemological orientation toward texts that regard them as human constructions, who probably can and should be interrogated (Reisman, 2012). Wineburg distilled three heuristics namely "sourcing", "corroborating" and contextualizing in order to engage students in the cognitive analysis of sources. This framework by Wineburg is designed to engage learners in the epistemological analysis of text to enable them to think critically and historically about primary sources. Learners are therefore encouraged to "read like historians".

The cognitive analysis of the sources focuses on the theme of the Vietnam War 1968 to 1969. The reason for the choice of the theme is that sources that are used in this theme are mostly primary sources or secondary sources which are autobiographies of the participants in the war. This theme demonstrates the power of primary sources when listening to the emotions of those who participated in the war compared to a historian who represented the events through the eye of the eye-witness or participant and therefore it is primary sources that provide an accurate insight into what actually happened during the Vietnam War. Although twenty-five sources were analysed, only fourteen were evaluated in detail across the three textbooks in order to provide empirical evidence about the use of primary sources in the representation of the Vietnam War. Wineburg (Cited in Mayer, 1999) has likened the historian's work to that of a necromancer. Wineburg emphasises that "good historians bring back the dead, get them to talk with one another, and leave us with the yarn" (Cited in Mayer, 1999:66). In support of his perspective, Wineburg, argues that "by using primary documents such as diaries, letters, newspaper accounts, and oral interviews, students hear the arguments put forth by historic actors and directly experience the tensions and inner motives which lie at the heart of a given narrative" (Cited in Mayer, 1999:66).

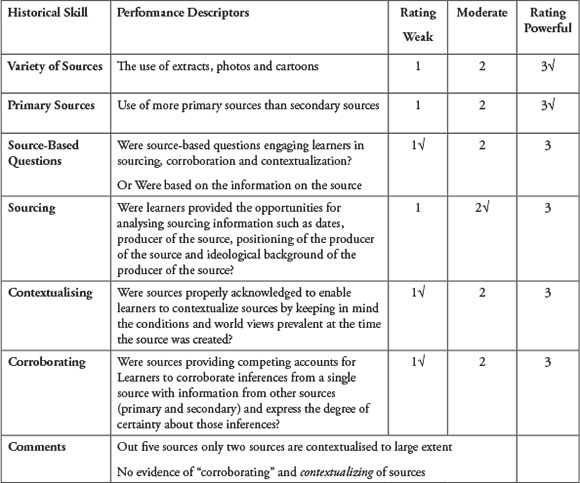

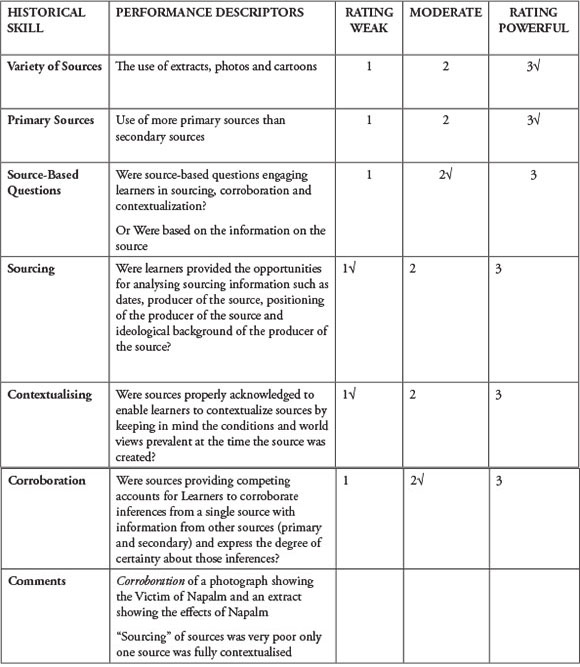

An instrument containing the framework of historical thinking, developed by Seixas and Morton (2013) and Wineburg (2001) was designed to evaluate the three textbooks. The instrument comprises three heuristics and various forms of sources. The items were divided into three categories, variety of sources, primary sources, source-based questions, "sourcing", corroboration and contextualization and the criteria is divided into three levels, namely, weak, moderate and powerful use of elements of primary sources (Refer to Annexure A).

Interrater-reliability has been utilised in this study in order to promote the credibility, dependability and trustworthiness of the findings. A subject specialist who majored in history and who possesses extensive teaching and moderation experience in the subject at national level was used to apply the criteria of evaluation on the three textbooks. The specialist was briefed by the researchers in terms of the criteria as articulated by Seixas and Morton (2013) and Wineburg (2001) and he used the same instrument to judge the textbooks. His scores were used to corroborate the scores of the researchers to promote the reliability of the outcomes.

Literature review

In this section four studies will analysed which are based on the three heuristics developed by Wineburg. Two of the studies are from international research and are based on the analysis of primary and secondary sources. The studies are conducted by Wineburg (2001) and Mayer (1999). The other two studies are based on the South African context and are focused on the analysis of sources and source based questions in Grade 10 textbooks and school-based examination question papers developed across three schools in KwaZulu-Natal.

Utilising the three heuristics that he has developed, namely, "sourcing", "corroborating" and "contextualising", Wineburg (2001) compared eight historians and eight high school students, using a "think aloud" strategy to evaluate their cognitive thinking when working with sources. Wineburg (2001) notes that historians identified a document's subtext or hidden message by considering it as both a rhetorical artefact and as a human instrument. Wineburg (2001) explains the meaning of the subtext by indicating that the subtext is not the literal text but the text of hidden and latent meaning. For a historian to be able to identify the subtext, he needs the background knowledge or factual knowledge of the period outlined by the source. Students on the other hand failed to identify a subtext. Another paradox between historians and high school students related to beliefs about the texts and the conception of the primary documents. Whereas historians considered information about the text, such as who wrote the text and at what time, to be very important; students focused on the information in the text. Reading texts seemed to be a process of gathering information for students, with texts serving as bearers of this information. On the other hand, historians seemed to view texts as social exchanges to be understood, puzzled about regarding the intentions of the author, and situated in a social context. Historians also managed to use corroboration heuristic influenced by their epistemological beliefs about the nature of historical evidence (Van Boxtel etal., 2007). For historians, corroboration was indispensable because every account was seen as reflecting a particular point of view while students focused on issues of bias. In addition, the students gave more importance to textbooks, whereas the experts ranked primary sources higher (Van Boxtel et al., 2007; Wineburg, 2001).

Mayer (1999) is an education expert who utilises the cognitive framework of analysing historical sources developed by Wineburg. The study is about two primary documents, namely, a diary written by David Golighdy Harris, a middle-level white planter from South Carolina and the second source is a record of testimony given in the U.S. Senate by Henry Adams, a freed slave and African-American activist living in Louisiana. According to Mayer (1999) these particular documents were written in the second half of the nineteenth century and represent two opposing perspectives on the events occurring during the era of reconstruction. Students begin the process by considering the documents themselves and the documents' authors in order to identify aspects of sourcing heuristic. Later students were asked to reconstruct the basic message of each author and then examine similarities and differences in the messages in order to corroborate the information in the two sources. Although the documents were coming from diametrically opposing vantages, there are indeed issues that Adams and Harris agreed upon. Both observed and reported violence against the freed slaves. Both noted that the freed slaves did not trust their former owners and finally, both discussed the fact that the freed slaves had a tendency to run away from the plantations on which they had previously worked (Mayer, 1999:68). There are also disagreements and Mayer asks questions as to what needs to be done if there are differences identified during the process of corroboration: What do historians do when documents present differing perspectives? What should students do? To make sense of differing perspectives contained in primary documents, Mayer argues, historians employ a third heuristic: contextualizing. That is, they place documents within the frame of a particular time. The contextual knowledge students bring to the documents will aid them in reconciling differences between the two reports and ultimately aid in generating an overall account (Mayer, 1999:68).

Waller (2009), a master's degree student at the University of KwaZulu-Natal explored Grade 10 textbooks in a dissertation entitled "How does historical literacy manifest itself in South African Grade 10 textbooks?". The purpose of the study was to identify and explain historical literacy and its various forms in Grade 10 textbooks. She used a conceptual toolkit developed from the theories of Taylor, Wineburg and Lee as conceptual framework that includes amongst others, knowing and understanding historical events, historians' craft, narratives of the past, historical concepts, empathy and so on. She evaluated the preface, three purposive activities and the jacket cover of the three Grade 10 textbooks namely, New Generation Textbook 10, Looking into the Past and Marking History Grade 10 and compared these with textbooks written prior to 1994 (Waller, 2009). Seven textbooks writers were interviewed on the role of school history. The research under the heading historical craft focuses on the three heuristics such as "sourcing", "corroborating" and contextualizing which are used by historians to analyse sources. In her attempt to outline the cognitive analysis of sources through the use of the three heuristics, Waller (2009) does not provide evidence for the existence of "sourcing" in textbooks and the importance ofprimary sources has not yet been emphasised in historical literacy because primary sources are also a manifestation of the most reliable information because the producers of the sources are either participants or eye witnesses. The heuristics of corroboration, although thoroughly explained, was addressed in a superficial manner and there was no indication whether primary sources were corroborated with other primary sources or secondary sources because without this process the historical literacy would be considered to be unreliable.

Bertram (2008) is another author who evaluated activities that relate to the implementation of the National Curriculum Statement. She used the learning outcomes and assessment standards in order to evaluate the assessment tasks and tests from three sampled schools in KwaZulu-Natal namely, Enthabeni High School (rural school with African learners), Lincoln High (in a middle class white suburb and learners mostly whites) and North High (with Indian staff and a majority Black and few Indian learners). The schools selected performed between 80% and 100%. She analysed tests that were set by each school as well as the exemplar set by the then Department of Education. She evaluated 72 sources and according to her, the sources were fully referenced because learners were given the name, the occupation of the writer, the purpose for which the source was produced and the date on which it was produced. According to her findings level one questions requiring simple extraction of information were endemic across the schools. The strength of the research was that the author managed to use "sourcing" information in order to judge the effective use of sources. The shortcoming of this study is that there was no evidence of the use of "corroborating" and contextualizing. There is no mention of comparisons across the sources, be they primary sources or secondary sources. The author arrived at an inference that "doing history" compromises "knowing history". The "knowing history" perspective is anathema to a social and cultural constructivism which advocates knowing through doing. As Von Glasersfeld himself says, "knowledge is the result of an individual subject's constructive activity, not a commodity that somehow resides outside the knower and can be conveyed or instilled by diligent perception or linguistic communication" (Von Glasersfeld, 1990:37).

The four studies provide evidence of how the three heuristics were utilised in the analysis of primary and secondary sources. In the first study, the students had to identify the sub-text and rank documents in terms of their trustworthiness and in the second study, the students were required to identify the sourcing heuristics and apply the corroboration and contextualizing heuristics. Contextualizing was utilised to make sense of the differences in documents and this can be done by exploring the ideologies that were at play during the production of the sources. The two studies emphasise the importance of primary sources as authentic sources in the reconstruction of historical knowledge. The third and fourth studies that are based in South Africa were more focused on the "sourcing" heuristic and there was limited evidence of the use of corroboration and contextualization heuristics.

Conceptual framework

There are two epistemological stances or beliefs in the construction of historical knowledge, namely, a conservative realism and radical deconstructionist or relativist. Conservative realism advocates a scientific approach that conceptualized the discipline in terms of its ability to represent the knowable past. The radical deconstructionist on the other hand posits that reality is constructed. Ginzburg (Cited in Neumann, 2010:491), one of the historians, warns that the focus on history as "representation" leads to "a general rejection of the possibility of analysing the relationships between these representations and the reality they depict or represent; this is dismissed as an unforgivable instance of naive positivism. He is supported by Neumann and VanSledright. In his work with fifth-grade students, VanSledright (Cited in Neumann, 2010:491) uses a less radical epistemology. Although influenced by a deconstructionist epistemological stance Neumann recommends a radical realism as a compromise between the two paradoxical pools, conservative realism and radical deconstructionist perspectives. According to Neumann, critical realism rejects the possibility of "objectivity" as naïve and instead recognises that an interpretation is never free from the reader's presuppositions and is subject to revision, but simultaneously insists that an interpretation can bear an adequate correspondence to the past. Critical realists assume further that the identity of the author and the historical context in which the author originally composed a text are relevant in determining meaning. Cautious, critical reading of texts does potentially yield an accurate, though tentative reconstruction of the past. The critical realism is congruent with the framework of the cognitive analysis of sources (Neumann, 2010:491). Critical realism as the epistemological stance that offers a balanced reading of sources was followed when dealing with sources in this article.

A conceptual framework for historical thinking has been conceptualized by Seixas and Morton (2013) in a book entitled the "Big six concepts of historical thinking". According to Seixas and Morton, historical thinking is a creative process that historians go through to interpret the evidence of the past and generate the stories of history. Historians use primary sources as evidence and ultimately the foundation for all claims in history are the traces left over from the times in which past events occurred; marking a historical claim that others can justifiably believe, then, requires finding, selecting, contextualizing, interpreting and corroborating sources for an historical argument (Morton & Seixas, 2013). This article will focus on one of the critical elements of historical thinking - the analysis of primary sources and would use the cognitive evaluation of sources designed by Wineburg (2001) as a conceptual framework. The cognitive analysis of primary sources is critical and demonstrates a sophisticated nature of the discipline of history that should be reflected in the classroom and therefore learners should be engaged in this rigorous process of constructing historical knowledge (Morton & Seixas, 2013, 2013). The cognitive analysis process comprises three heuristics distilled by Wineburg (2001) and supported by Seixas and Morton (2013), namely, "Sourcing", Collaborating and Contextualizing and these would be used to evaluate the use of sources in these three textbooks.

It is critical to explain the three heuristics in detail because these would be used as criteria to judge the trustworthiness of the sources. "Sourcing" according to Seixas and Morton (2013) is the first step in analysing any source. "Sourcing" begins with straightforward queries: When was this written? Who wrote this? What were his or her positions? Many accomplished students will move on to difficult questions to answer: Towards what was the author's attitude? It involves inferring from the source the author's or creators' purposes, values and world view, either consciously or unconsciously (Seixas & Morton, 2013).

Contextualizing the documents encourages historians and students to analyse sources by considering the perspective of the time and the society in which they were created (Seixas & Morton, 2013). The context can assist historians or students to understand their situation and interpret their words accurately. The following questions can assist the students to contextualize sources: What was going on in this society at the time the picture was taken that might help students interpret the photograph? A source should be analysed in relation to the context of its historical setting: the conditions and worldviews prevalent at the time in question (Morton & Seixas, 2013).

Corroboration, according to Wineburg (2001), is the general skill of checking facts or interpretations from a particular document against other, independent sources. Corroboration involves directly comparing the information from the various sources to identify which important statements are agreed on, which are uniquely mentioned, and which are discrepant. Students must be able to handle the multiple documents, to assess whether they reinforce each other and also where and why they contradict each other (Morton & Seixas, 2013). Often, however, information is not corroborated, and as a result the student may judge information to be tentative until corroborating information is located (Wineburg, 2001).

Findings on the analysis of textbooks

Discussions on the findings based on the Vietnam War 1968 - 1969

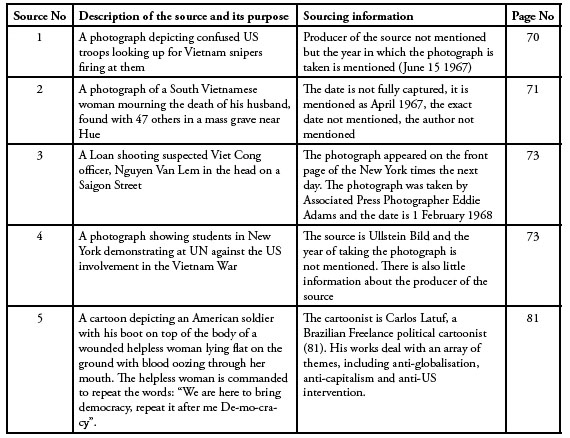

The tables below attempt to analyse four to five sources in textbooks in terms of their sourcing information as well as the message that is communicated by the sources. Photographs, cartoons and extracts have been described and the messages they are communicating have been recorded on the table. The page numbers in which the sources are located in the textbooks are indicated on the tables. Sources are named as sources 1 to 5 in each table. However, these sources are named differently in different textbooks. Some of the extracts will be reflected word for word from the textbooks in order to demonstrate the inability of the authors of the textbooks to utilise the "sourcing", corroboration as well as contextualization heuristics. The researchers will also provide examples of how some of the sources could have been used in order to reflect "sourcing", corroboration and contextualization.

Table 1: Via Africa History

This table indicates elements of sourcing as well as the description of the information on the sources, numbering of sources as well as the page numbers where these sources can be located in Via Africa History textbook.

These photographs that are used in Via Africa textbook are suitable for effectively teaching historical skills such as analysis of primary sources because they provoke emotions and come from a participant or eye-witness. However, what is rather disquieting is that these sources have not been identified as sources and there are no activities relating to these photographs, instead the authors grouped six cartoons as sources 1 to 6 in which the source-based questions are based. Photographs are primary sources and a cartoon is an opinion by the cartoonist and the person drawing it and is mostly not a participant or eye witness and can easily be classified as secondary source. The six cartoons that are being used are mostly anti-Americans and there is no balanced perspective. The authors should have used a combination of cartoons and photographs in the chapter as well as extracts of speeches of American leaders which would be biased towards America. What is the purpose of having photographs that were not used in activities to corroborate the narrative constructed by the authors with the cartoons or other primary sources produced by eye-witnesses?

Another challenge about the photographs is that the producers of the sources are not mentioned and the absence of this information leads to speculation about the author and his or her ideological affiliation. The absence of the period in which the photographs were taken undermines them as primary sources and as authentic photographs depicting an accurate picture of what happened during the Vietnam War. There are many questions that can be asked. What was the positioning of the photographer during the war? What was the photographer's intention in taking these photographs that demonstrate cruelty of the Americans troops in Vietnam? Was the photographer a South Vietnamese, North Vietnamese or an American? What is clear is that these photographs demonstrate anti-American sentiments. Why are these photographs not showing the American soldiers making progress during the course of the war? Is it because some Americans sympathised with the Vietnamese or fellow soldiers who were suffering in Vietnam or was the photographer a communist who wanted to expose the cruelty ofthe Americans troops? The information about the producer of the sources is critical in order for historians, learners and teachers to understand the purpose of the source and what the source is doing (Wineburg, 2001). It seems that these sources were influencing people against America during the war.

Source 5 has more information about the author of the cartoon who is a Brazilian with an anti-capitalist political perspective and it is clear he was against the US and against capitalism and the message on the cartoon mocks the United States. This cartoon depicts an American soldier with his boot on top of the body of a helpless and wounded woman lying flat on the ground and commanding her to say the words "we are here to bring democracy" and asking the woman to repeat the word "De-Mo-Cra-Cy". The only information lacking, is the date on which the cartoon was drawn and the newspaper in which it was published. This weakness is endemic in all six cartoons used in this chapter (Grove et al., 2013:80). The period is important because it may provide the information about whether the cartoon was a protest against the attack on Vietnam in order to provoke people against the war or after the war in order to shame the Americans.

The source- based questions posed on these cartoons are as follows: What is the message of the cartoonist? Is the message biased? Provide evidence from the source to substantiate your view. Explain the usefulness of the sources to historians studying the war. These are simple questions, not challenging and they would not enable learners to reflect on the sophisticated nature of the discipline.

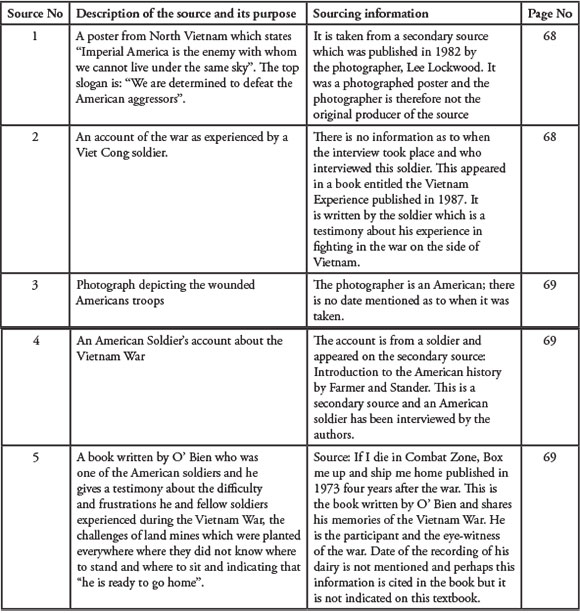

Table 2: Spot On History

This table indicates elements of sourcing as well as the description of the information on the sources, numbering of sources as well as the page numbers where these sources can be located in Spot On History.

Source 1 is a poster but it was photographed and the photographer is not the primary producer of the source because the composer of the poster appears to be the Viet Cong. The message clearly shows that the poster was developed by the Vietnamese who wanted to encourage people to rise against the American attack. The poster must have been issued during the war. The absence of critical information leads to this type of speculation (Morton & Seixas, 2013). Source 2 is a primary source, namely, Vietnam Experience written by a Vietnamese soldier. Although it was written by the participant, the exact date on which the soldier wrote the information is not mentioned and what is stated is only the date in which the book was published. If the book was written based on memories and the soldier did not keep a diary, some information may be distorted and exaggerated to present the Americans in a bad light because the writer was a Vietnamese soldier. A photograph of the wounded American troops was taken by an American whose intention might be to expose the suffering of the American troops in Vietnam in order to encourage the American citizens to protest against the war as it is endangering its own soldiers in pursuit of the so-called democracy. Source 4, is a secondary source: Introduction to the American History and the account by the soldier is an extract from the secondary source but the information is relevant and can be used to corroborate other sources. Source 5 is written by an American soldier who participated in the war and the title is very emotional - If I die in Combat Zone, Box me up and ship me home. This title relates to the message about the agony suffered by American troops. It is necessary to ask the following questions: When was the source written? Did the soldier keep a diary of the war as it unfolded or were memories recollected after the war? It is common place that some soldiers do keep a war diary. How accurate are these sources that were written by participants but published long after the war?

It is necessary to establish the reliability of information about the war and testimonies of the soldiers that wrote about the war need to be corroborated. Two of the three sources will be used as an example of the corroboration which was missed by authors of Spot On History:

Source 1 (Labelled in the book as Source B): An account of the war as experienced by a Viet Cong soldier:

Because we were weaker than the Americans, not even as armed as the North Vietnamese soldiers, we had to be patient and use our intelligence. We laid traps, ambushes, using simple deadly weapons - sticks smeared with excrement, arrows tripped off by the unwary soldiers. His automatic rifle and grenade would keep us in firepower for weeks. The Americans were well armed and clumsy, they had firepower that we feared, so we stayed hidden and out of range. They were elephants, especially when moving through the jungle. We moved in cells of three, lightly armed but traveling silently and quickly. If we wounded or killed only one of theirs and lived to fight another day, it was a victory. Like the drop of water that wears away the stone we would wear away the American army (Dugmore et al., 2013:69).

Source 2 (labelled in the textbook as Source E): Tim O' Bien served in the Vietnam War. His book entitled, If I die in a Combat Zone Box me and Ship me home, is an intense personal account of his time of duty from 1968 to 1969 during the war:

You look ahead a few paces and wonder what your legs will resemble if there is more to the earth in that spot. Will the pain be unbearable? Will you scream or fall silent? ... Once in a while we would talk seriously about mines. "It's more than the fear of death that chews on your mind; one soldier, nineteen years old, eight months in the field, said- It's an absurd combination of certainty and uncertainty: The certainty that you're walking in mine fields, walking past the things day after day, uncertain of your every movement, of which to shift your weight, of where to sit down. There are so many the VC can do it. I'm ready to go home (Cited in Dugmore et al., 2013:69).

Source 3 (labelled in the textbook as Source D): An account of the war experienced by an American soldier:

American troops have been told we were defending a free democracy. What I found was a military dictatorship rife with corruption and venality (greed) and repression. The premier of South Vietnam openly admires Hitler. Buddist priests who partitioned for peace were jailed or shoot down in the street. Extract from: Introduction to the American History, 2002, Author Farmer and Stander (Cited in Dugmore et al., 2013:69).

A careful analysis of the three sources is that two of them are books written by participants and source 3 is a secondary source where the American soldier's account was recorded. Between the three sources, which source can be corroborated? Sources 1 and 2 by soldiers from Viet Cong and America can be corroborated. Although from diametrically different vantage points, there are similarities between the two sources. Both sources confirm that the American troops were traumatised by traps and mines, both agree that Americans troops were being killed slowly and both confirm that Viet Cong were winning the war. There are minor differences; the Viet Cong soldier mentions traps while the Americans express agony and fear of being wounded by the traps and to reconcile the two sources background information about the American strengths in aerial bombardment and Vietnamese strengths in Guerrilla War tactics can assist to reconcile the two minor differences identified. Both sources are primary sources and it is very effective to corroborate two primary sources as demonstrated by Mayer's (1999) study of the two primary sources developed from different perspectives. However, the author of Spot on History did not corroborate the two sources but attempted to corroborate Source 2 and Source 3 labelled in the book as sources B and D respectively. In an attempt to ask the question based on two sources, the following question was asked: Both sources A and B are eye witness accounts of the war experienced in Vietnam. How reliable are both sources as accounts of the Vietnam War? The corroboration is that both were Americans troops and both were unhappy about their roles in the Vietnam War and there is some form of corroboration. However, the question is not asking for corroboration or comparison but requires the students to indicate whether they are reliable or not. The learners would indicate that both soldiers were participants in the war and the information provided should be reliable. The question requiring corroboration should have been framed in this fashion: In what ways is Source B supporting the information in source D? However, sources B and D are not related except for the fact that they were testimonies by two American soldiers but are focused on different subjects: one on the regime of South Vietnam and another on the war and it is difficult to employ contextualization heuristic if sources that are being compared are not reflecting the same event.

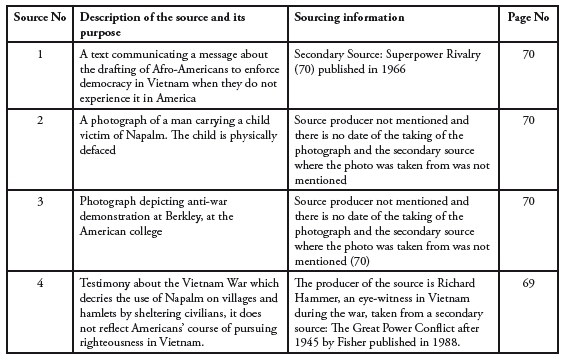

Table 3: Focus History

This table indicates elements of "sourcing" as well as the description of the information on the sources, numbering of sources as well as the page numbers where these sources can be located in Focus History.

The analysis of the information shows that information from primary sources such as testimonies of participants and photographs demonstrated a high level of emotions which are not found in secondary sources. Source 1 is from a secondary source: Superpower Rivalry and the extract message is encouraging Afro-American citizens to be drafted into the army. Source 2 is a photograph which is emotional because it shows a child who has been deformed by Napalm. The sourcing information about the photograph is lacking and it is, therefore, an obstacle to be used for corroboration and contextualization because sources that are used for these heuristics must have been produced simultaneously. Source 3 is a photograph depicting anti-war protests by students and the photographer and the period in which the photograph was taken are not mentioned. Source 4 is a secondary source but written through the eye of an eye witness of the Vietnam War, Richard Hammer who is featured in a book entitled The (Great Power Conflict after 1945 written by Fisher. In the source Richard Hammer, criticises the use of Napalm by the American troops. Source 2 and Source 4 can be corroborated because both address the issue of Napalm. The only challenge is that "sourcing" information about the producer of Source 2 is lacking and therefore it can be dismissed as unreliable.

The following extract is an example to demonstrate how sources could be used to employ corroboration heuristic: Source 4 (labelled in the textbook as Source F): Richard Hammer, an eye-witness in Vietnam during the war, comments on American policies:

One does not use napalm on villages and hamlets sheltering civilians ... If one is attempting to persuade these people of the rightness of one's cause. One does not blast hamlets to dust with high explosives from jet planes in the sky without warning - if one is attempting to woo the people living there to the goodness of one's cause ... One does not defoliate (destroy vegetation in) a country and deform its people with chemicals if one is attempting to persuade them of the enemy's evil nature. (Fisher, The great power conflict after 1945, Cheltenham: Tanley Thomas, 1998:60) (Cited in Fernandez et al., 2013:69).

Source 1 (labelled Source A in the textbook): An extract from the statement of a civil rights group in the civil rights movement and war in Vietnam, 1966:

We maintain that our country's cry of 'preserve freedom in the world is a hypocritical mask... 16% of the draftees from this country are negroes called on to preserve 'democracy' which does not exist for them at home (J Brooman & S Judges, superpower rivalry, Harlow: Longman, 1994:28) (Cited in Fernandez et al., 2013:70).

The two sources are secondary sources, source 4 featured an eye-witness and not a participant and it is difficult to locate the role of this witness. For example, who is Richard Hammer? What was his role or position during the war? Is Hammer an American, British or Russian? The absence of "sourcing" information leads to speculation. Source 1 is a secondary source and members of civil rights movement were against the war and were fighting for the rights of the Afro-Americans. It is difficult to corroborate secondary sources and it is necessary that more primary sources should be used by textbooks' writers in order to engage learners in the analysis of sources.

Summary of the findings

Variety of sources

a. Authors of the Spot On History textbooks have used a variety of sources from primary sources to secondary sources and have also used extracts, cartoons and photographs and these primary sources are made available to the learners' teachers to construct historical knowledge in the classroom. Focus History used mostly secondary sources although there was a quotation made by an eye-witness. This was not adequate in demonstrating sufficient use of primary sources. Via Africa History on the other hand uses sources such as cartoons and photographs that reflect the events and there is limited use of extracts from the soldiers and eye witnesses.

b. There is evidence of the use of primary sources across the three textbooks eventhough these sources do not reflect all the characteristics of primary sources or "sourcing" heuristics. Spot On History uses primary sources that were better contextualized compared to Focus History and Via Africa History.

c. The three textbooks used testimonies of the participants or soldiers and eyewitnesses in sources which demonstrated some characteristics of primary sources.

d. Spot On History uses testimonies of both the Vietcong and American soldiers which were useful in providing a balanced perspective.

e. There was a limited use of photographs. The three textbooks prefer to use cartoons and extracts and photographs have been used only by Focus History in one instance.

Source-based questions

a. Spot On History and Focus History use a variety of sources and activities and questions were asked on the variety of sources. However, Via Africa History uses six cartoons and ignored photographs in the source-based exercises and the textbook was deficient in the use of extracts from participants and eyewitnesses.

b. The questions posed by Spot On History in the comparisons of sources between the two testimonies did not accurately address the corroboration heuristic and the authors missed an opportunity of "corroborating" evidence between the testimonies of two soldiers from Viet Cong and US perspectives. The two testimonies should have corroborated effectively because the American soldier laments the agony of fighting in the Vietnam War while the Viet Cong soldier articulates the effectiveness of the traps and there is irony in the two sources, Viet Cong soldiers were celebrating the victory and the Americans were lamenting the loss. The contrast should have encouraged the authors to use contextualization heuristic in order to defuse this tension as demonstrated by Mayer (1999). These types of sources are useful because they are coming from opposing perspectives and there is agreement and disagreement between them.

Sourcing heuristics

a. All three textbooks do not reflect all the characteristics of "sourcing" such as the name of the producer of the source and the date in which the source was produced. Some mentioned the year in which the photograph was taken but not the exact date.

b. There was an attempt by Spot On History in the four sources analysed to provide the information about the producer of the source, the date of the source and the position of the producer of the source but this was not widespread in other sources. For example the three accounts by soldiers who participated in the war, the information about the name (Soldiers), position (Vietnam soldier or US soldier) were provided and so two elements were complied with but there were no dates in which the sources were produced because the dates mentioned are for publication of the books written by the two soldiers from different vantage points.

c. Focus History, was very deficient in its presentation of photographs without the photographer and the date in which they were published and this is evident in the photograph of the child who was a victim of Napalm and two other photographs that are based on the Vietnam War (Fernandez et al., 2013:70). However, the extract used on Napalm was better contextualised.

Corroboration and contextualization

a. Among the three books only Focus History posed an activity that relates to corroboration between a photograph showing the child wounded by Napalm and an extract from an eye-witness decrying the effects of Napalm on innocent civilians. The shortcomings of these sources are that the photograph was not properly contextualized, because the name of the photographer and the date on which it was taken are not mentioned.

b. There was no evidence of contextualizing because of the lack of the date in which sources were produced. The date is essential in providing the background of the period when events were taking place. Another obstacle was the comparison between sources that are not focused on the same event as evidenced in the Spot On History about the source which focuses on the regime and another focusing on the war. Spot On History also missed an opportunity to engage in corroboration and contextualisation because the sources selected by the authors were suitable for these two heuristics.

c. Via Afrika History demonstrated no evidence about corroboration and contextualisation and the sources selected in the Vietnam theme were also not suitable for the engagement of learners in the two heuristics.

Epistemological beliefs

The analysis of the sources across the three textbooks on the Vietnam War reveals an epistemological belief of authors who wrote the textbooks. There seems to be a conception about history as a compendium of historical facts or a mere listing of events and this is evident in the manner in which the authors dealt with sources where the focus was on the information on the source rather than the producer of sources. It is a concept which has influenced the writing of history in the past about knowing historical facts as opposed to constructing historical knowledge. For a shift to take place there is a need for a change in the epistemological belief by authors of textbooks to accommodate a critical realism which embodies both elements of realism and relativism.

There has been a shift in the writing of textbooks with the inclusion of a source-based approach but the deficiency in the accommodating primary sources with all the "sourcing" information clearly shows that sources are just treated as another form of narrative or story which contain facts that need to be assimilated and therefore the constructive perspective which is congruent with "doing history" in the classroom has been undermined by the three textbooks on this theme of Vietnam War.

Conclusion

In conclusion the analysis of the three textbooks clearly shows that they are still framed in an outdated mode of writing textbooks even though all three contain sources and source-based questions. With special focus on the theme on the Vietnam War, regarding the use of sources and primary sources in Spot On History were better contextualized than other sources and the authors of this textbook also used a variety of primary and secondary sources which include cartoons, testimonies of soldiers who participated in war on both sides of Vietnam and US. The sources attempt to provide a balanced perspective about the war. There were opportunities for corroboration and contextualization of sources but opportunity was not utilised by the authors. With regard to Focus History, photographs were poorly contextualized and only extracts from secondary sources were properly contextualized and there were limited primary sources used by this textbook and this is considered an obstacle to the construction of historical knowledge. The Via Afrika History contained suitable photographs which contained some sourcing information but these were not used in the source based activities, instead cartoons were used in the analysis of sources.

What is common across the three textbooks is that there was more attention focused on the information on the sources and questions were based on comprehension of the information on sources rather than on the "sourcing" heuristics about who produced the source and when the source was produced.

This was caused by the epistemological belief of authors about history as a corpus of historical facts rather than the manifestation of historical thinking skills and therefore sources are merely seen as another collection of facts. There was also limited evidence of the use of corroboration and contextualization heuristics across the three textbooks. It is recommended that the Department of Basic Education should introduce the cognitive framework in analysing sources which should be embedded in its curriculum documents as well as in textbooks. DBE should encourage textbooks' writers to develop resource packs that contain primary sources that are fully contextualized in order to complement the textbooks that appear to be deficient in dealing with primary sources.

References

Barton, KC & Levstik, LS 2004. Teaching History for the common good. Mahwah, NJ: bLawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Bertram, C 2008. 'Doing history?': Assessment in history classrooms at a time of curriculum reform. Journal of Education, 45:155-177. [ Links ]

Black, DA 2014. Indoctrination to indifference? Perceptions of South Africa secondary school History education with special reference to Mpumalanga, 1960-1912. Unpublished Ph.D thesis. Pretoria: Unisa. [ Links ]

Bottaro, J, Visser, P & Worden, N 2013. In search of History Grade 11, Learners book. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Boyatzis, R 1998. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Britt, MA & Anglinskas, C 2002. Improving students' ability to identify and use source Information. Cognition and Instruction, 20(4):485-522. [ Links ]

Bruner, JS 1986. Vygotsky: A historical and conceptual perspective. In: JV Wertsch (ed.). Culture, communication and cognition: Vygotskian perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2012. Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statements. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2014. Standardised national question papers. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Dugmore, C, Friedman, M, Minter, L & Nicol, T 2013. Spot On History Grade 12, Learners book. Gauteng: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Dryden, S 1999. Mirror of a nation in transition: History teachers and students in Cape Town schools. Unpublished M.Ed dissertation. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Engelbrecht, A 2008. Role reversal in history textbooks after apartheid. South African Journal of Education, 28(4):519-541. [ Links ]

Fernandez, M, Wills, L, McMahon, P, Pienaar, S, Seleti, Y & Jacobs, M 2013. Focus History Grade 12, Learners book. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Gaventa, J & Cornwall, A 2006. Power and knowledge. In: P Reason & H Bradbury (eds.). Handbook of action research. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Grove, S, Manenzhe, J, Proctor, A, Vale, P & Weldon, G 2013. Via Africa History Grade 12. Cape Town: Via Afrika Publishers. [ Links ]

Kallaway, P 1993. History of education in a democratic South Africa, Yesterday & Today, 26:10-18. [ Links ]

Mayer, RH 1999. OAH Magazine of History, The progressive era, 13(3):66-72. [ Links ]

Moses, AD 2005. The public role of History, Hayden White, traumatic nationalism, and the public role of History. History and Theory, 44:311-332. [ Links ]

Neumann, DC 2010. What is the text doing? Preparing pre-service teachers to teach primary sources effectively, society of History education, The History Teacher, 4:489-311. [ Links ]

Reisman, A 2012. Reading like a historian: A document-based History curriculum intervention in urban high schools. Los Angeles: Routledge. [ Links ]

Siebörger, R 2005. The dynamics of History textbook production during South Africa's educational transformation. In: K Crawford & S Foster (eds.). What shall we tell the childen? International perspectives on school History textbooks. Greenwich: Information Age Publishing. [ Links ]

Seixas, P & Morton, T 2013. The big six historical thinking concepts. Nelson Education: Toronto. [ Links ]

Seixas, P 1993. The community of inquiry as a basis for knowledge and learning: The case of History. American Educational Research Journal, 30(2):305-324. [ Links ]

Stearns, PN, Seixas, P & Wineburg, S 2000. Knowing, teaching and learning history: National and international perspectives. New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Tharp, G & Gallimore, R 1988. Rousing minds to life: Teaching, learning, and schooling in social context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Van Drie, J & Van Boxtel, C 2007. Historical reasoning: Towards a framework for analyzing students' reasoning about the past, Educational Psychology Review, 20(2):87-110. [ Links ]

Von Glasersfeld, E 1990. An explosion of constructivism: Why some like it radical. In: RB Davis, CA Maher, & N Noddings (eds.). Constructivist views on the teaching and learning of Mathematics. JRME Monograph, Virginia, NCTM. [ Links ]

Vygotsky, LS 1978. Mind in society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Waller, BJ 2009. How does historical literacy manifest itself in South African grade 10 history textbooks? Unpublished M.Ed dissertation. Pinetown: University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Wineburg, S 1999. Historical thinking and other unnatural acts, Phi Delta Kappan, 80:488-99. [ Links ]

Wineburg, S 2001. Historical thinking and other unnatural acts: Charting the future of teaching the past. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [ Links ]

Yilmaz, K 2006. Social Studies teachers' conceptions on history and pedagogical orientations towards teaching history. M.Ed dissertation. Athens: University of Georgia. [ Links ]

Annexure A: Criteria used to evaluation the four textbooks

Focus History

Rating Scale

Spot On History

Rating Scale

Via Africa History

Rating Scale