Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Yesterday and Today

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9003

versão impressa ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T no.14 Vanderbijlpark Dez. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2015/nl4a1

ARTICLES

Political economy of History textbook publishing during apartheid (1948-1994): Towards further historical enquiry into commercial imperatives

Ryota Nishino

Division of History University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji. nishino_r@usp.ac.rj

ABSTRACT

The provision of textbooks in apartheid South Africa (1948-1994), a source of controversy and media interest in recent years, is placed in historical perspective, with particular reference to History textbook production. Michael W Apple (1993) proposes an analytical framework of political economy to enable better understanding of the tensions behind textbook production and distribution. During apartheid bureaucratic structures and commercial imperatives gave rise to a conformist ethos that stifled innovation. The textbook approval and adoption processes led publishers into adopting strategies to ensure approval for and approval of their textbooks. To avoid friction with education departments, editors urged self-restraint on their writers and instructed them in how to write officially approvable manuscripts. While some authors were disappointed, most wrote to satisfy their publishers, often resorting to copying the content and style of previously-approved textbooks. Focusing on History textbooks as a field of publishing history, this study synthesises existing primary and secondary sources, further supplemented by interviews with former History textbook writers and editors.

Keywords: Textbook publishing; Textbook adoption; South Africa; History education; Apartheid

Introduction1

Amongst numerous education and curriculum issues, the textbook, History textbooks in particular, can evoke passionate discussion. Parents and policymakers have legitimate concerns about the best use of public funds for the teaching of History at primary and secondary school levels. This article focuses on South Africa during apartheid (1948-1994), which enacted a most blatant form of institutionalised racism and segregation. During apartheid South African History textbooks attracted both international and domestic criticism for their potential to shape the minds of the youth who would invoke a common historical narrative that legitimised the apartheid regime, be it overtly or subtly. For the majority of the pupils in apartheid South Africa, whether they are in an ethnic minority or majority group, History accumulated notoriety over decades. It was regarded as an exercise in rote-learning and as a conduit for state-sponsored indoctrination whose functions and purposes under apartheid included the strengthening and preservation of Afrikaner nationalism, white exclusivism, Christian National Education and Separate Development (Boyce, 1962; Auerbach, 1965; Cornevin, 1980; Dean, Hartmann & Katzen, 1983; Van den Berg & Buckland, 1983; Kallaway, 1984, 1993, 1995, 2002).

The end of apartheid presented educationists and curriculum designers with the eagerly awaited opportunity to overhaul the apartheid-era History curriculum, and for History textbooks to respond more wholesomely to the challenge of nation-building. Nearly ten years into a democratic South Africa, the National Department of Education accepted the realisation that a complete break from the apartheid-era History curriculum and teaching practices would not be immediately feasible or possible, advocating instead lessons to be learned by stakeholders from hindsight. In this context, in its progress report on the South African History Project, issued in 2003, the Department urged "history researchers and scholarly writers to engage in a combined effort to review, revise and rewrite outmoded apartheid-era school history texts" (Department of Education, 2003:6). In 2012, in a review of the most recent version of the "new" History curriculum, the Curriculum Assessment Policy Statement, an historian of South African education, Peter Kallaway, argued that historical research into apartheid-era History education is rapidly fading into the mists of time, while History educators have found themselves having to defend the viability of History in the post-apartheid era (Kallaway, 2012:26). In recent years, the provision of textbooks has been characterised by "crises" and "sagas" in the delay or non-delivery of textbooks in the Eastern Cape and Limpopo provinces. These issues would appear to undermine the recent reversal of the status of the textbook from a text to be transmitted unmediated to pupils, an approach which dominated ideas about historical knowledge during apartheid, to the constructivist approach advocated in Curriculum 2005 (Chisholm, 2012).

Research into textbook publication seems to be a burgeoning field. It has attracted wide interest from scholars of various disciplines such as textual analysis, studies on nationalism, and international relations (Hein & Selden, 2000; Barnard, 2003; Klerides, 2010; Repoussi & Tutiaux-Guillion, 2010). The social and cultural approach to education and education research that gained ground after the 1970s resulted in historians of education beginning to investigate the ways in which state-sanctioned national identity was transmitted through the History curriculum, the textbook and pedagogy (Phillips, 1998; Grosvenor, 1999). While these studies have been valuable in situating the production of textbooks in a socioeconomic and political context, more can be achieved to expand and enrich the study of the textbook by situating it in an historical context. If media coverage serves as a measure, a report on the apartheid-era textbook approval and provision practices suggests it is scarcely an issue that should be consigned to the dustbin of History (Whitaker, 2010). Historians of education would help advance the discipline if they examined more closely how textbooks were produced and circulated during apartheid. This article approaches the political economy of textbook publishing as a historical enquiry, and uses apartheid-era History textbooks as a case study. Future research may provide a more rounded picture of the complex educational bureaucracy and substantiate numerous anecdotes associated with the textbook publishing industry during apartheid. Contribution by researchers with sufficient command in multiple languages is particularly welcome.2

This article analyses the commercial imperatives that shaped the political and cultural ethos of textbook publishing during apartheid. In the 1980s Philip Altbach and Gail Kelly saw the textbook as a complex educational medium whose production demands co-ordination of the educational system, the national finances, the publishing industry and the public consciousness (Altbach & Kelly, 1988:6 in Chisholm, 2012:9). As a result of such arguments, questioning about who co-ordinates the delicate balance of interests involved in the process of textbook production has added additional fuel to the textbook debate. The educationist Michael W Apple conceived of textbook production as contestation between hegemonic and counter-hegemonic parties over pedagogy, content, the role of teachers and the administration of schools. Though the American and South African markets are different, Apple's political economy approach has merit for it regards the textbook as:

... not simply 'delivery systems' of facts'. They are at once the results of political, economic, and cultural activities, battles and compromises. [Textbooks] are conceived, designed, and authored by real people with real interests. They are published within the political and economic constraints of markets, resources and power. And what texts mean and how they are used are fought over by communities with distinctly different commitments and by teachers and students as well (Apple, 1993:46).

Apple's conceptualisation rests on his concern with the political economy of the textbook, and demands an understanding of the bureaucratic mechanisms that influence the ways in which the bureaucracy, the publishers and the writers operate. These demand an understanding of those processes and the power dynamics of various stakeholders that regulate the dissemination of historical knowledge and pedagogy. Apple's stress on "real people with real interests" is noteworthy for its reminder of the multiple influences that operate on and make up the political economy of the textbook. A case in point in South Africa is the syllabus revision of the early-1980s that gave way to a number of alternative textbooks to the long-selling series by established publishers. The Joint Matriculation Board, which administered private schools, adopted analytical and interpretive approaches to its History syllabus from the 1970s. In the mid-1980s, the Natal and the House of Delegates education departments revised their History syllabus, incorporating a similar pedagogical approach to that of the Joint Matriculation Board (Kallaway, 1995:13).

Two decades since democracy in South Africa the time is ripe for an analysis of disparate primary and secondary sources on the processes of History textbook publication. Ifhindsight can prove useful for the present and future, this article looks into an under-researched issue of the roles played by the bureaucratic regulations, and the responses by publishers and authors. Correspondence with the textbook writer and the doyen of Afrikaner historiography, Floors van Jaarsveld, serves as revealing examples of the publishers' commercial imperative.3 The publishers had to contend with commercial interests, which affected both their relationships with authors and the textbooks as final outcomes. Alternative textbooks published for "open" schools fall outside the purview of this article, although this is another field that could enrich the historical enquiry into South African History textbooks.4 It is hoped that the gaps in this article will point to a direction for future research.

South African History textbook publishing: Textbook industry profile

During the apartheid-era the South African publishing industry was dominated by educational publishing, which included school textbooks. For instance, the available data from 1990 show the domestic book trade to have grossed an estimated R431.5 million. Out of this total, the sales of educational publications brought in R344.4 million, or 77% of the total (Joubert, 1990:Appendix 1).

A distinct feature of the apartheid-era textbook industry was the domination of the market by white-owned publishers; "black" publishers of commercial significance were few. In her study of the South African publishing industry, Susan Joubert compiled a list of textbook titles adopted by the Department of Education and Training (DET) for its primary and secondary schools in 1990. Of the top ten publishers, the top three were Afrikaner publishers (Educum, a Perskor subsidiary, 20%; De Jager-Haum, 16.7%; and Via Afrika, a Nasionale per subsidiary, 14.3%) - their combined share was 51% of the total. The fourth and fifth largest were the non-Afrikaner companies such as Juta, and Shuter and Shooter at 10.5% and 9.1% respectively. These top five publishers accounted for over 70% of the total. The remainder was taken up by Maskew Miller (5.8%), Nasou (4.9%), Boekateljee (4.2%), Dynamic Books (2.0%), and Oxford University Press (1.7%) (Joubert, 1990:Appendix 4).5 Textbooks for black schools were typically published by subsidiaries of white companies. For instance, Via Afrika and Nasou, subsidiaries of the Afrikaner publishing house, Nasionale Pers, sold textbooks in the homelands and "independent" homelands of Bophuthatswana, Transkei, Ciskei and the Northern Transvaal. Thus, profits from textbooks sold to schools in the Homelands were channelled back into the parent publishing houses (Mpe & Seeber, 2001:21, note 19).

Despite these large sales figures, the textbook publishing industry was derided as "the Cinderella of publishing", being perceived as lacking the glamour of other realms of publishing (Diamond, 1991:60). The most attractive reward for the textbook publisher was the certainty of sales. Once a textbook title was adopted by an Education Department, the department would purchase a set number of the textbooks for its schools. Only then did the publisher know the size of orders and subsequent print-runs. In other areas of commercial publishing, the publishers typically speculate on how many copies could be sold and determine the volume in a print-run. In textbook publishing the de facto guaranteed sales eliminated the time-consuming and costly practice of collecting and disposing of remainders (McCallum, 1996:58-59). Furthermore, textbook sales were boosted by mandatory bilingual legislation that applied to all textbooks. During apartheid textbooks were not considered by education departments for commission and purchase unless they were available in both English and Afrikaans. Despite the costs and the time required for the translation, it potentially broadened the market to include both Afrikaans- and English-medium schools (Thompson, 1985:54).6

Another incentive for textbook publication was the schools' high demand for replacements. As a general pattern, schools would loan the textbooks to students free of charge on an annual basis. Education departments budgeted for a five-year textbook working life before needing replacement. Ensuring adequate maintenance and the return of the textbooks fell to the schools, which were permitted to order a limited number of replacement copies each year (Siebörger, 2006:242, note 11). This demand grew with the spread of the school boycotts across many townships during the 1980s. The increase in the theft and damage to textbooks coincided with the escalation of school boycotts. Textbooks were often not returned at the end of a school year. Even if they were returned, in whatever condition, many schools had poor storage facilities, which reduced the lifespan of textbooks or made them vulnerable to theft (Monyokolo, 1993:13-14,18). In the Johannesburg area alone, 280,000 copies, worth R7 million, were lost annually (Diamond, 1991:61). Thus, contrary to the accepted wisdom of free market principles, while the textbook market seemed lucrative, it was a market shaped and controlled by the powers and policies governing textbook approval and adoption.

Textbook approval process: "Don't rock the boat"

Apple's conceptualisation of the textbook as a reflection of market, resources and power raises questions about how textbooks were certified and adopted for use in schools during apartheid. Creating coherent historical narratives of the History of History textbooks awaits thorough treatment by researchers with competency in African languages and Afrikaans, as well as knowledge and experience of educational bureaucracy. These researchers may investigate the inner-workings of the Afrikaner-dominated and homeland education departments and supplement the gap in the available literature in the English language.

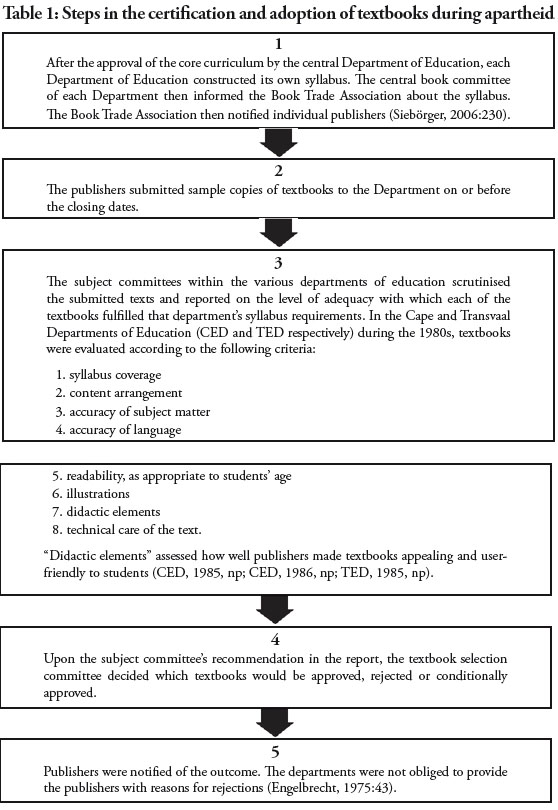

The general pattern and model ofthe textbook approval and adoption process in South Africa was not a centralised one: during apartheid the individual education departments conducted their own textbook approval. However, a few accounts suggest the textbook approval processes in these departments followed broadly the same five steps:

While the overall process can be generalised, variations across the different education departments presented practical issues to publishers. It was acknowledged that the Homelands tended to follow the procedures of the Department of Education and Training (DET), the department responsible for "black" students in "white provinces". The Transvaal and the Cape departments (TED and CED), together with the DET, were known to be the most controlling of the education departments (Kantey, 1992:11). Publishers were notified that the Cape and the Transvaal departments considered only bound page-proof copies (Engelbrecht, 1975:35; Joubert,1990:15; Kantey, 1992:11). This requirement presented a serious dilemma for textbook publishers. A letter written in February 1991 from a textbook publisher to one of the interviewees in this study who was involved in textbook production states, "Our very big problem is that [education] departments now require submission in page proof form. This, of course, entails a tremendous amount of work, including final art work". The failure to submit the manuscript on time resulted in the publishers' missing the selection round, reducing to waste the effort and expense already channelled into the production of their textbooks (Monteith, 1985:14; Moss, 1993:24; Mpe & Seeber, 2000:21; Siebörger, 2006:9-10).

Having the textbooks inspected and gaining the approval of the various education departments was only one step towards the eventual sales. Another crucial step was to have them put on to lists of approved textbooks. Just as there were differences in the levels of control in the approval process, the fragmented education bureaucracy - a manifestation of the ethnically-divided apartheid state machinery - gave rise to overlapping selection and adoption policies by education departments. Most education departments issued 'approved textbook' lists from which schools could choose. The DET limited the number of the texts on the list per course per Standard to six, the Transvaal department set its limit to three (Engelbrecht, 1975:31; Kantey, 1992:11-12). However, in the TED, there was no guarantee that this limit would always be observed (Engelbrecht, 1975:31). In one instance of readers for literature studies, out of 45 anthologies (also known as "readers") submitted to one education department, six titles went on to the list of adopted books (Joubert, 1990:15). It appears that not all education departments excluded teachers from the selection of textbooks. While the Cape and Natal provinces accorded more autonomy to teachers in evaluating textbooks, the Orange Free State allowed teachers to make recommendations but principals retained the right to choose the textbook (Engelbrecht, 1975:42-43). Since most Homeland authorities replicated the DET textbook lists, having their textbooks on the DET list was, for publishers, critical (Chernis, 1990:302; Monteith & Proctor, 1993:37; Moss, 1993:24).

Notwithstanding the differences, for much of the apartheid era the education departments conducted selection and approval of textbooks. Prima facie, this seems plausible considering that the textbooks are purchased from the tax revenue. The education departments informed the publishers of their decisions. Most manuscripts were approved on condition that specific changes were made. There was little opportunity for publishers and authors to challenge the departments' instructions for amendments. Publishers often found it confusing when a department announced a rejection but offered no reasons. The task of informing the writers of the outcomes of the approval fell to the publisher; the authors amended the text for resubmission (Kantey, 1992:12).

A few interviewees in this study, who had written textbooks during apartheid, admitted that they were initially naïve and unaware of the power dynamics of textbook publishing. They had initially perceived the textbook publishing industry as following a top-down model in which, to have the textbook approved, the publishers needed to comply with the Department's instructions. They saw this ethos as giving rise to a risk-averse and conservative outlook amongst the publishers and an ethos that stifled innovative approaches to presenting historical information. Soon they realised that the publishers were primarily interested in satisfying their financial motives rather than questioning the level of control the education departments were imposing on publishers. These authors found it frustrating and disheartening to see their editors discouraging and disapproving of their initiatives to include new historical content and innovative pedagogical approaches (Interviews 18 February 2004 & 20 February 2004).

Commercial constraint: Tender price

As Apple points out, the political economy of the textbook requires us to think about the available resources invested by the state in the provision of textbooks. From the 1960s, education departments purchased textbooks and stationery from the same channel of funds, thus placing further constraints on the costs of textbooks (Evans, 2002:193). An education department's textbook budget determined how many copies could be distributed to students, and effectively set the "tender price" or de facto price cap on each copy.

Textbook publishers at this time were acutely aware of the cost of textbooks and the implications for sales. In a letter dated 28 August 1959 to historian and History textbook author, Van Jaarsveld, his publisher advised him against publishing his textbook in two separate volumes because it would increase the cost and deter potential buyers:

The price difference between [rival publisher'] two and our one book is exactly 5/6 [five shillings and sixpence] [...] Our travellers [sales representatives] report daily that the schools dont have money and a price difference of more than 5/- [five shillings] will tip the scales. Then intrinsic value and quality no longer count for a headmaster. (Letter to Floors van Jaarsveld, 28 August 1959)

This letter underlines publishers' sensitivity to the financial concerns of schools and provides a glimpse of the conflict of desires and interests between the writer and the publisher.

We do not know whether the above is an isolated example of a conflict of interests, or one of many such interchanges over a number of years. Suffice to say that publishers' concerns with the cost of textbook production seemed to persist well into the late 1980s. Joubert's study provides an example from the late 1980s. Out of the textbook budgets in the DET, R5 was estimated as the "tender price" for a copy. This was deemed sufficient to support a textbook of 80 to 90 pages. The publishers needed to sell at least 20,000 copies to recover the production cost. Joubert contends that the price ceiling could have stymied the development of good-quality textbooks. The publishers opted for lower-quality paper and sacrificed visual aids to cut the production costs. In addition, they were unable to attract suitably-qualified and experienced authors to develop the textbooks. The textbook publishing industry became a game of bottom-line production rather than production aiming for higher quality (Joubert, 1990:15-16; Interviews 14 February 2004 and 18 February 2004).

Publishers' response 1: Collusion between publishers and education department officials

A review of these textbook approval and adoption processes clearly indicates that the education departments during apartheid assumed and ensured a monopoly in textbook approval and adoption policies and processes. Difficult to ignore in the various accounts - published, unpublished and anecdotal - are the allegations of secrecy on the part of the education departments regarding those policies and processes (Moss, 1993:25-28; Proctor & Monteith, 1993:32; Mpe & Seeber, 2002:18-23). These allegations take the form of criticism of the lack of accountability for decisions, and claim collusion between education department officials and the publishers. Although more investigation of this is required for full substantiation of these allegations, that of collusion stems from well-known connections between Afrikaner publishers, especially of newspapers, and National Party politicians. For instance, DF Malan, Prime Minister of South Africa from 1948 to 1954, had been the editor of a Nasionale Pers newspaper, Die Burger, from 1915 to 1924. Two prominent leaders of the National Party, and also Prime Ministers, HF Verwoerd and BJ Vorster, served on the Perskor Board of Directors (Mpe & Seeber, 2002:19-20; Giliomee, 2003:417, 550).

A former textbook writer relates long-standing rumours in the industry about department officials accepting offers to write textbooks, and their names appearing as authors despite their often negligible contributions. This kind of "patronage" on the part of publishers and education departments was said to put these textbooks in an advantageous position for manuscript approval and adoption by the Department (Interview 14 February 2004). Furthermore, syllabus committee members were often involved in writing textbooks before the final syllabus was completed, and were even receiving royalties of between 10% and 15%. These involvements flew in the face of the prohibition of department officials' participation in textbook writing (Kantey, 1992:11; Moss, 1993:28; Siebörger, 2006:239).

Dismissing such allegations as mere anecdotes may not be warranted. Persistent rumours of rampant corruption prompted President FW de Klerk to appoint a commission to investigate the DET in 1990. The four-part report, Kommissie van Ondersoek na Aangeleenthede Rakende die Department van Onderwys en Opleiding (Commission of Enquiry on Matters Concerning the Department of Education and Training), was released in 1992. Mareka Monyokolo confirms that de Klerk's report discusses the issues of corruption and malpractices in financial accounting and corrupt practices in textbook production and distribution in the DET (Monyokolo, 1993:35, note 13). However, only the Afrikaans edition of the report was available at the time of my own enquiry. This is an area that can be best pursued by researchers with a solid command of Afrikaans who, with an additional understanding of DET education policies, can reveal and interrogate the details of the report.

My research into the archives illuminates the practice of honorary authors dating back to as early as 1959, as shown in a letter from an editor at Voortrekkerpers to Van Jaarsveld:7

Natal is a province which is fast becoming densely populated and there is definitely a market for such a series of books [...] The Voortrekkerpers will be very happy if you would undertake the great task. Keeping in mind the huge amount of work you have already done, one hesitates to ask you. But we believe however that this too will be very rewarding for you.

Mr X [name altered] is our link with Natal. He is an inspector of education with great influence that means a tremendous amount to us. We therefore would like to mention at this stage that we would like his name on the book for obvious reasons [.] He also recommends that we should add the name of a pure-bred Englishman from Natal. He is at present busy trying to find such a person. If the Englishman and Mr X make a contribution we can give them a small royalty - if not, Voortrekkerpers will recompensate [sic] them for the use of their names (Letter to Floors van Jaarsveld, 1 September 1959).

The editor tries to persuade him to add the names of not one, but two, Departmental personnel for "obvious reasons" - selling his textbook in Natal. The editor requests him to agree to have their names on the book to boost the prospect of adoption and of sales. This is but one piece of correspondence with his publisher that Van Jaarsveld kept - most of which was in Afrikaans. I was unsuccessful in locating his reply to the editor but those proficient in Afrikaans may be able to do so because he kept carbon copies of his own letters.8

Publishers' response 2: Desperate measures for desperate times

Tight timeframes set by education departments presented authors and publishers with practical constraints on the developing of good-quality textbooks. The length of time considered sufficient to develop a textbook may vary from one author or publisher to another. By way of a guideline, in a study of textbook publication in the mid-1990s, Kate McCallum estimated that producing a high quality textbook would require at least three years from the beginning to the completion of the process. The steps she outlined involved preliminary market research, recruitment of authors, research into the contents and pedagogy of the subject area, design, drafting of manuscripts, editing, trialling in schools, final revision, submission for approval, printing, marketing and distribution (McCallum, 1996:58). The reality of textbook production during apartheid was very different. A letter sent by a publisher to another textbook author in 1984 communicated the deadline set by the Transvaal Education Department. The TED announced the submission dates for Standards 9 and 10 textbooks to the publisher: 28 February 1985 and 3 August 1985 respectively, the manuscripts to be available in both Afrikaans and English by that date. The letter was dated 31 October 1984. The letter ends by saying, "[a]s we have so little time it is absolutely imperative that we receive the manuscript as soon as possible". This is not an isolated example. As the table indicates, at this time the publishers typically began the writing process when they received syllabi from education departments. A former editor recalls that education departments at the time distributed syllabus documents to publishers only in the second half of 1984. The departments expected the new textbooks to be ready for submission in early 1985, allowing the publishers an unrealistic six months to complete manuscripts (Monteith, 1985:13). The tight timeframe was not peculiar to the 1980s. One interviewee recalled his first textbook project in the early 1970s. The writer remembered the whole writing process was "very rushed". He wrote a chapter on a period of History about which he as writer had no expert knowledge, and had in fact replaced another author who had opted out of the project (Interview 27 February 2004). It seems that the publishers simply forced their authors to meet the departmental deadlines, rather than requesting the education departments to extend them.

Time pressure, together with the commercial imperative, gave rise to plagiarism of textbooks. A former textbook writer and editor recalled textbook authors replicating existing textbooks. The rationale for this practice was that the authors were in effect denied time to write a new manuscript using original research. Simply following, and to a large extent replicating, textbooks that had already been approved and adopted by education departments was easier (Interview, 4 Dec. 2003). Studies by Merle Babrow and Leonard Thompson found that a textbook by C Fowler and GJJ Smit, New History for Senior History Certificate and Matriculation, closely followed works by the prominent historian in Settler historiography, George McCall Theal. Originally published in 1931, the textbook went through multiple revisions and editions until its discontinuation in 1974 (Babrow, 1962:63; Thompson, 1985:57-58).9Unlike scholarly works, textbooks do not typically list sources, nor are they required to do so. This loophole in the textbook writing conventions seemed to have aided and abetted the persistence of plagiarism over decades.

This trend persisted throughout the apartheid era and even into the early post-apartheid era. Using textual analysis, I interrogated the History textbook written by Settler historian George McCall Theal in 1891: Short History of South Africa 1486-1826: For the use of schools. I then compared Theal's textbook with 30 Standard 6 History textbooks published between 1945 and 1996.10 The comparative study focused on one of the most frequently discussed "border wars" - the Fifth Anglo-Xhosa War of 1818-1819. The analysis makes obvious the extent and significance of the influence of Theal's textbook and his narrative on the writing of apartheid-era History textbooks. Most of the textbooks analysed were consistent with Theal's version of the conflict in characterising the war as a clash between the two "races" - the British and the Xhosa - in which the Xhosa were in the wrong. From this it can be deduced that apartheid era textbooks reflected the government's official rhetoric of separate development in subtle ways. A handful of History textbooks published after the mid- to late-1970s condemned the British for meddling with the Xhosa people and attributed the war to cultural misunderstandings, the implications of this interpretation being that peace would have been maintained had the two groups remained separate. The textbooks that appeared in the late 1980s and the early 1990s laid the blame for the ongoing conflict on the white settlers and exposed the white settlers as relying on the Dutch and the Khoi reinforcements against the Xhosa. While these shifts may indicate the weakening hold of the apartheid regime on apartheid ideology, these textbooks continued to narrate the war according to Theal's framework of "racial conflict". This example underlines the government's continued role in the screening and adoption of textbooks even in its final years (Nishino, 2008:06.7-06.11). Only after the demise of apartheid did two History textbooks denounce the "racial conflict" model and offer a materialist interpretation of the war (Nishino, 2008:06.12).

Publishers' response 3: Self-censorship

The publishers responded to the commercial imperatives by reducing the possibility of their being rejected by the education departments. These responses took several forms of self-restraint, the most explicit being that of urging the textbook writers to exercise caution in their choice ofwords, warning that the textbook would not be published unless it gained departmental approval. It seems that the Afrikaner authors were also under pressure, even during the National Party's rule. Many South Africans who grew up during apartheid would remember Van Jaarsveld, not as a high priest of Afrikaner historiography as historians would, but as the author of numerous History textbooks. A publisher's editor wrote to the young Van Jaarsveld in April 1957 advising him to make several changes to his manuscript. The editor wrote: "The following sentence worries me [the editor]", singling out a sentence in his original manuscript: "In the stars the face of people could be read [...] Today we still fear the number 13. No hotel has a room 13".

The editor expresses his concern with this sentence: "We Christians do not believe in fate because it is a heathen [pagan] concept. Show the learners that Christians should not be so superstitious as to fear the number 13". The editor also focuses on his [the author's] description of the relationship between the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch Reformed Church. He writes: "Along with van Riebeeck the Dutch Reformed Church came to S.A. ... Under the [Dutch East India] Company only one church denomination was allowed, viz. the D.R. Church".

The editor comments on these two sentences:

Here we now again have to do with the name of the church. I think we should be careful. Ought we not steer around the whole matter? ... The Ref[ormed] Church contends that the Ref. Church was re-founded in 1859. My position becomes a bit thorny (Letter to Floors van Jaarsveld, 16 April 1957, National Archives Pretoria, Floors van Jaarsveld Collection, A.2055, underlining in the original).

The editor advises Van Jaarsveld to "be careful" and even to "steer around the whole matter" when dealing with van Riebeeck and the Dutch Reformed Church, the denomination perceived to be the bastion ofAfrikaner nationalism and the National Party, in the same breath. Indeed, the editor may well be pointing out that the Reformed Church (Hervormde) would concede to the Dutch Reformed Church (Nederduits Gereformeede) as the first church in South Africa.11 Yet, what seems to concern the editor is that, at face value, Van Jaarsveld's original text would draw criticism from education departments for it can create an impression that van Riebeeck placed the Dutch Reformed Church in a subordinate role.

These examples illustrate a publisher's in-house measure to avoid friction with the education departments and to avoid the risk of a costly rejection. However, the likelihood exists that the authors of textbooks would see such caution not only as an affront to their writing but as in-house censorship. This censorious and conservative trend seems to have persisted even in the last years of apartheid. The Department of Education and Culture (DEC), a national body for white provincial departments, sent a revealing explanatory letter in December 1988. Addressing a textbook author, the DEC expressed the view that "some aspects [of a manuscript] have been treated in a manner that is causing dissatisfaction to readers in a Christian Society, the principles of which are being upheld by the Department". It seems that religion was a sensitive concern for education departments in the context of maintaining the principles of the National Education Policy Act of 1967, which enshrined Christian National Education. As a result publishers came to rely on authors who were known to be sympathetic to Afrikaner nationalist historiography (Kros & Vadi, 1993:92-93; Proctor & Monteith, 1993:37).

Commercial imperatives tend to manifest in more subtle measures of self-restraint and censorship exercised by both the writers and the publishers. Editors during apartheid also developed a "feel" for selecting those writers who would cause least friction with the editors and other writers. A judicious publisher or editor would appoint a team of writers comprising an appropriate mix of subject specialists and teachers who had strong collegiality and commitment, and shared a common vision in History teaching and learning (Interviews 15 December 2003, 30 January 2004, 18 February 2004, 27 February 2004). In other cases, editors found it difficult to work with writers with little experience of writing school textbooks according to this model. The editors found it frustrating to work with authors who did not appreciate or possess the skills needed to write age-specific prose, and who were impervious to the editor's advice to modify the register of a text. Having to work with "slow writers" also made an editor's life difficult. If the deadlines were not met, the publishers would face the many ill consequences of missing the approval rounds (Interview 17 February 2004). While some authors found this kind of clash with the editors frustrating and disheartening, seasoned authors simply developed a co-operative approach to ensure that the textbooks would be published. As interviewees related, the seasoned editors had learned that the standards of checks varied. Some department personnel were more concerned with spelling and factual accuracy than with ideological references and implications. Thus both editors and writers developed a "gut feeling" for what department selection committees were looking for in a textbook. They learned what to write and what not to write to satisfy the departments, and used this knowledge to ensure that their textbooks would pass the approval test. What concerned the department selection committees most was whether the textbooks featured the contents prescribed in the syllabus, often in the same order as those in the syllabus documents. If a textbook featured contents not prescribed in the syllabus, the writer would feature these but in a "boxed text" to indicate extra content

Publishers' response 4: Self-withdrawal

If in-house editorial intervention is a manifestation of commercial imperatives affecting textbooks, withdrawal from an approval process is an escalation of the commercial imperative. The fragmented approval and adoption processes during apartheid made it possible for one textbook to be approved by one education department but rejected by another.

In this context the case of the History Alive series published by Shuter and Shooter is worth documenting. The series took advantage of the national syllabus revision of 1983, which yielded to a new orientation of History as an academic subject. In particular, the revised documents of 1985 in the Cape and Natal provinces recast History as "an academic discipline and [a set of] intellectual skills and perspectives" (Cape Education Department, 1985:191; Natal Education Department, 1985:2). The authors and editors of the History Alive series who were interviewed welcomed the syllabus revision and saw the revision as a fillip for new kinds of History textbooks. They expected the revision to encourage the all-important Matriculation examinations to shift the emphasis in History as a subject from rote-learning to the acquisition of analytical skills. It was further hoped that teachers would adapt their pedagogy and seek textbooks that catered to the needs of the revised syllabus (Interview 18 February 2004; Interview 27 February 2004).

The series had varied receptions from education departments. The Transvaal Education Department rejected History Alive for Standards 7, 8 and 9 without explanation, and approved the texts for the lower standards after changes were made. As of September 1987, this series was approved for use in white schools in Natal (Natal Education Department), and in Coloured (schools under the House of Representatives) and Indian schools (House of Delegates) (Business Day, 1987). The series was popular in private schools administered by the Joint Matriculation Board whose examination and pedagogical styles were compatible with History Alive. The series gained a reputation for its innovative pedagogical approaches, new contents that refuted age-old historical myths, and its inclusion of some "left-wing" historical interpretations (Interview 27 February 2004).

The 1987 approval round in the Transvaal stirred controversy amongst the education and publishing communities. For Standard 10 History, the Transvaal Education Department adopted History Standard Ten by CJ Joubert and JJ Britz and replaced AN Boyce's History for Standard Ten, which had been adopted by the TED for 25 years. The National Minister of Education at that time, Piet Claase, claimed that the Joubert and Britz textbook was the only title submitted for approval. However, it soon emerged that five textbooks had been submitted, including Boyce's. These developments incensed a sizeable portion of the Transvaal education community: the English-speaking teachers' union, the Transvaal High School History Teachers' Association (all English-speaking teachers) and the parents' lobby group (Nishino, 2011:57- 58).12

What did Shuter and Shooter do amidst the controversy? It was reported that they decided against submitting the manuscript of History Alive Standard 10 to the TED because they felt it was not worth risking its rejection (Business Day, 1987). In one sense, this decision indicates the publishers had exercised the ultimate form of control - self-withdrawal. In thus making a business decision to "cut the losses", the publisher knowingly avoided unnecessary strife and costs in dealing with the education departments that would almost certainly reject the manuscripts. Simultaneously, however, the teachers and parents groups, as well as the learners, in the Transvaal missed the opportunity to have the series as a teaching and learning resource. However, the series defied the rejection by the TED and continued to sell elsewhere, such as the House of Delegates Department that administered the "Indian" population. The publisher anticipated the imminent end of apartheid and commissioned a series for DET schools, Discovering History. This series retained the pedagogical orientation of its predecessor, but made its prose and tasks more accessible to students in DET schools (Interview 15 December 2003).

Conclusion

Following Apple's model of textbook production, this article hopes open scholarly enquiry on the commercial imperatives that faced the textbook publishers, editors and writers during apartheid will continue. The article has attempted to show how they responded to these market forces. This article does not intend to be the definitive or comprehensive account. From the evidence examined, textbook industry during apartheid offered a few significant profit incentives to publishers and the various education departments remained dominant in the textbook approval and adoption processes during the period. The lack of transparency that characterised the selection and approval processes bred persistent allegations of collusion, which continued to dog both publishers and the bureaucracy. The use of honorary authors, in-house screening before submission, and the selection of co-operative or "colluding" authors were among the strategies publishers and editors developed. Consistently rigid and tight timeframes not only stifled the development of textbooks of quality, but compelled writers to engage in de facto plagiarism of textbooks that had successful records in the selection and approval processes; the publishers acquiesced in and encouraged such practices. Combined with these constraints, the de facto price-caps on the textbooks gave rise to an additional commercial concern for textbook publishers and one that compromised the educational concerns of the pupils and teachers. The nature and extent of these constraints engendered an ethos that encouraged and rewarded conformity rather than innovation amongst publishers and authors. This said, innovation in officially-approved textbooks occurred after syllabus revision gave way to, and included, a revision of pedagogy. Nonetheless, further research on textbook production will deepen our understanding of textbook production.

References

Altbach, P & Kelly, G 1988. Textbooks and the third world: An overview. In: P Altbach & G Kelly eds.). Textbooks in the third world: Policy, content and context. New York and London: Garland Publishing. [ Links ]

Apple, MW 1993. Official knowledge: Democratic education in a conservative age. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Auerbach, FE 1965. The power of prejudice in South African education: An enquiry into History textbooks and syllabuses in the Transvaal high schools of South Africa. Cape Town: Balkema. [ Links ]

Babrow, M 1962. A critical assessment of the work of George McCall Theal. Unpublished MA dissertation, Cape Town: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Barnard, C 2003. Language, ideology, and Japanese History textbooks. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Business Day 1987. Publisher won't deal with TED, 25 September. [ Links ]

Boyce, AN 1962. The criticism of school history textbooks. Historia, 7(4):232-237. [ Links ]

The Cape Education Department, Departmental Book Committee (Secondary) 1985. Review Form. Peter Kallaway personal collection, Mayibuye Archives, Belville. The University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

The Cape Education Department 1985. Junior secondary course: Syllabus for History. The Education Gazette 84(4):190-199. [ Links ]

The Cape Education Department 1986. Departmental book committee (secondary) Review Form. August. [ Links ]

Chernis, R 1990. The past in service of the present: A study of the South African school history syllabuses and textbooks, 1839-1990. Unpublished D.Phil thesis. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Chisholm, L 2012. The textbook saga and corruption in education. South African Review of Education, 19(1):7-22. [ Links ]

Cornevin, M 1980. Apartheid: Power and historical falsification. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Department of Education (South Africa) 2003. South African history project, progress report 2001-2003: Incorporating the report of the history and archaeology panel to the minister of education (update 2003), 4. Pretoria: Department of Education. [ Links ]

Diamond, D 1991. Education publishing. In: South African Library (eds.). Book publishing in South Africa for the 1990s: Proceedings of a symposium held at the South African Library, Cape Town, 22-25 November, 1989. Cape Town: South African Library. [ Links ]

Engelbrecht, SWH 1975. The School textbook: A didactical-pedagogical study. Pretoria: South African Human Sciences Research Council, Institute of Education Research. [ Links ]

Evans, N 2002. "A textbook as cheap as a can of beer": Schoolbooks and public education in South Africa. In: N Evans & M Seeber (eds.). The politics of publishing in South Africa. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press. [ Links ]

Giliomee, H 2003. The Afrikaners: Biography of a people. London: Hurst & Company. [ Links ]

Grosvenor, I 1999. "'There's no place like home': Education and the making of national identity". History of Education, 28(3):235-250. [ Links ]

Hein, L & Selden, M 2000. The lessons of war, global power and social change. In: L Hein & M Selden (eds.). Censoring history: Citizenship and memory in Japan, Germany and the United States. Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe. [ Links ]

Holland, M 1993. General publishing in a textbook dominated market. In: S Kromberg, M Govender, N Birrell, & M Sibanyoni (eds.). Publishingfor democratic education. Johannesburg: South African Committee for Higher Education. [ Links ]

Joubert, SR 1990. Publishing in another South Africa: Problems and projections. Unpublished MPhil thesis. Stirling: University of Stirling. [ Links ]

Kallaway, P (ed.) 1984. Apartheid and education: The education of black South Africans. Johannesburg: Ravan Press. [ Links ]

Kallaway, P 1993. Historical discourses, racist mythology and education in twentieth-century South Africa. In: JA Mangan (ed.). The imperial curriculum: Racial images and education in the British colonial experience. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kallaway, P 1995. History education in a democratic South Africa. Teaching History, 78:11-16. [ Links ]

Kallaway, P 2002. Introduction. In: P Kallaway (ed.). The History of education under apartheid 1948-1994: "The doors of learning and culture shall be opened". Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Kallaway, P 2012. History in senior secondary school caps 2012 and beyond: A comment. Yesterday & Today, 7:23-62. [ Links ]

Kantey, M 1992. Book publishing in South Africa: A provisional sketch. Unpublished report for NEPI Curriculum Report. [ Links ]

Klerides, E 2010. Imagining the textbook: Textbooks as discourse and genre. Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society, 2(1):31-54. [ Links ]

Kros, C & Vadi, I 1993. "Towards a new history curriculum: Reform or reconceptualisation?" In: N Taylor (ed.). Inventing knowledge: Contests in curriculum construction. Cape Town: Maskew Millar Longman. [ Links ]

McCallum, K 1996. Educational publishing. In: B van Rooyen (ed.). How to get published in South Africa: A guide for authors, 2. Johannesburg: Southern Books. [ Links ]

Monteith, MA 1985. The making of schools' history textbooks in Natal. Unpublished conference paper presented at the 75th Anniversary of the University of Natal conference on the history of Natal andZululand,3, 2-4 July 1985, University of Natal (Durban). [ Links ]

Monyokolo, M 1993. Financing and provision of textbooks in South African black schools. Johannesburg: Education Policy Unit, University of the Witwatersrand and NECC. [ Links ]

Moss, G 1993. A critical overview ofeducational publishing. In: S Kromberg, M Govender, N Birrell & M Sibanyoni (eds.). Publishingfor democratic education. Johannesburg: South African Committee for Higher Education. [ Links ]

Mpe, P & Seeber, M 2000. The politics of book publishing in South Africa: A critical overview. In: N Evans & M Seeber (eds.). The politics of publishing in South Africa. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press. [ Links ]

Natal Education Department 1985. Syllabus for History lower grade Stds. 6-7. Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Nishino, R 2007. A comparative historical study of Japanese and South African school history textbooks ca. 1945-1995. Unpublished Ph.D thesis. Perth: University of Western Australia. [ Links ]

Nishino, R 2008. George McCall Theal and South African history textbooks: Enduring influence of settler historiography in descriptions of the Fifth "Frontier War" 1818-1819. In: P Limb (ed.). Orb and sceptre: Studies in British imperialism and its legacies, in honour of Norman Etherington. Melbourne: Monash University ePress. [ Links ]

Nishino, R 2011. Changing histories: Japanese and South African textbooks in comparison (1945-1995). Göttingen: V&R Unipress. [ Links ]

Phillips, R 1998. History teaching, nationhood and the state: A study in educational politics. London: Cassell. [ Links ]

Proctor, A & Monteith, M 1993. Textbooks, corruption and curricula. In: S Kromberg, M Govender, N Birrell & M Sibanyoni (eds.). Publishing for democratic education. Johannesburg: South African Committee for Higher Education. [ Links ]

Repoussi, M & Tutiaux-Guillon, N 2010. "New trends in History textbook research: Issues and methodologies towards a school historiography". Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society, 2(1):154-170. [ Links ]

Siebörger, R 2006. "The dynamics of History textbook production during South Africa's educational transformation". In: S Foster, & K Crawford (eds.). What Shall We Tell the Children? International Perspectives in School History Textbooks. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. [ Links ]

Thompson, L 1985. The political mythology of apartheid. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Transvaal Education Department (Sept. 1985). Comprehensive report. Pretoria. [ Links ]

Van den Berg, O & Buckland, P 1983. Beyond the History syllabus: Constraints and opportunities. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter. [ Links ]

Whitaker, M 2010. Textbook diplomacy, part 1. British Broadcasting Corporation. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p005x3w5. Accessed on 20 April 2015. [ Links ]

Interviews

4 December 2003: A former teacher of History, textbook writer and editor.

15 December 2003: A former school History teacher, later became a university lecturer.

30 January 2004: A former contributor to a History textbook.

14 February 2004: A former History teacher, and a university lecturer. A textbook writer at the time of interview.

17 February 2004: An editor in a publishing house.

18 February 2004: A former editor in a publishing house.

20 February 2004: A former History teacher and a textbook editor.

27 February 2004: Two former History teachers. Both taught at universities and wrote textbooks.

1 I am indebted to several readers who provided me with useful constructive criticism. My special thanks go to one reader and two anonymous reviewers of this journal. However, these readers remain beyond reproach. This article derives from my doctoral work at the University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia (Nishino, 2007). My field trip to South Africa between October 2003 and March 2004 was funded by the University of Western Australia Convocation Post Graduate Travel Award.

2 My first language is Japanese, and second is English. I do not know other languages.

3 Interviews with former textbook writers and editors were conducted between November 2003 and March 2004. To protect the identity of the interviewees the names will remain anonymous. All interviews were in English. I thank them for their largesse and time in agreeing to share their recollections, some of which were sensitive.

4 A challenge to state-approved textbooks emerged from the late 1970s when alternative textbooks promoted "struggle history" and targeted private and "open" schools. The projects tended to be small-scale projects because they were not dependent on government funding and catered only to a select clientele. The livelihoods of these alternative publishers often depended on the success or failure of a single book (Holland, 1993:110).

5 Joubert cites figures from DET Primary schools catalogue 1990 and DET secondary schools catalogue 1990.

6 African languages were not used as medium of instruction in secondary schools.

7 National Archives, Pretoria (NAP), Floors van Jaarsveld Collection, A, 2055. The letter was written in Afrikaans. I am indebted to the assistance of an anonymous translator for the English translation.

8 Afrikaner publishers had undergone mergers since the end of apartheid; personnel changes were common. I made repeated attempts to request interviews with (former) Afrikaner publishers and textbook editors, to no avail.

9 I thank an anonymous reader for advising me the end-point of the publication

10 The textbook was translated into Dutch in the same year and reprinted in 1891 as Korte Geschiedenis van Zuid- Afrika.

11 I benefit from the insight of an anonymous reviewer for this point.

12 The English-language newspapers reported the Transvaal textbook controversy extensively. See the reference section below for the list of articles I consulted.