Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.12 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2014

ARTICLES

The American Indian Civil Rights Movement: A case study in Civil Society Protest

Kevin A Garcia1

Michael Mount Waldorf School kgarcia@michaelmount.co.za / kagrc73@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) of 2012 focuses on certain aspects of the social upheaval the US experienced during the 1960s and 1970s. Under the heading of "Civil society protests of the 1950s to the 1970s", grade 12 learners examine the American Civil Rights and Black Power movements, the Women's movement, and the various peace movements, of that period. However, most South African educators and students are unfamiliar with another, similar movement of the same time period, the American Indian people's movement for civil rights. Some familiarity with this movement and its historical background may offer the classroom teacher an opportunity for the enrichment of historical study and learning. Knowledge of this movement can provide a broader context for the topics specified by CAPS. The history of the Native American peoples is often neglected in the study of US history. Just as the history of the African people of South Africa has become central to a complete understanding of the development of this country, so a renaissance in the study of American Indian history has become important in history teaching and learning in the United States. In particular American race relations issues are better understood in a context of black-white-Indian issues than in terms of a simple black-white bi-polarity. Furthermore, such awareness introduces the possibility for conducting comparative historical analysis in the South African classroom.

This paper first establishes the historical background of19th century white-Indian relations. This was a period of intermittent warfare, followed by treaty-making and the confinement of Indian people to reservations. From the 1880s onward, these reservations were all but destroyed by new government policy through the Dawes Act. The 20th century was a period of changed and changing government policy toward the Indian population. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 partially revived Indian tribal life. However, after the Second World War, further damage to tribal life was caused by the policy of the termination of relations between the government and the tribes. This led to the growing militancy of Indian response, in the 1960s and 1970s. The American Indian Movement (AIM) and other Indian organisations confronted the state and Federal governments, in Indian country and beyond, on reservations and in the US Supreme Court. These confrontations (from the late 1950s to the early 1970s) precisely coincide with the time period specified in CAPS. By the end of this period, the American public image of the Indian peoples had begun to change and a general awareness of Indian problems and issues began to express itself.

Keywords: Civil Rights; Civil Society; Native Americans; (Tribal) Reservations; Self-government; Sovereignty; Assimilation; Activism (Activist).

Interaction between the Native American peoples, and settlers from Europe and their descendants, constituting the white majority of the US population, is often an important but neglected theme in the study of American history. For example, American Indian activist and historian, Vine Deloria, Jr (Yankton Dakota) pointed out during the (1992) quincentennial of Columbus's first voyage to the western hemisphere, that what was "missing in this celebration (was)...the indigenous people" (Nabokov, 1991:XVII).

The national Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS), of 2012, places the study of the US Civil Rights Movement (Black Freedom Movement) in the South African Grade 12 programme of study. This essay will provide a brief examination ofAmerican Indian people's efforts to achieve a greater measure of civil rights with-in, and alongside of, the larger American society. With this further context of American race relations, the South African educator may have the opportunity to somewhat re-orient the study of the 1960s and 1970s, a period of upheaval across the US.

Pre-twentieth century white-Indian relations2

The North American Indian struggle for civil rights can be said to have commenced with the arrival of the Spanish under Christopher Columbus in 1492. Columbus captured as many as two dozen Taino Indians and took them with him, when he returned to Spain (Brown, 1971: 2; Sale, 1991: 122). Sustained interaction between native peoples and English-speaking settlers began in 1607 with the settlement of the colony of Jamestown, in Virginia. Although some of this early contact was characterised by co-operation and mutual support, conflict and open warfare commenced as early as 1610 (Brown, 1971:3-4; Sale, 1991:275, 278) and dominated the period leading up to American independence, in the war of 1775-1783 (Brown, 1971:chapter one; Calloway, 2012:chapters three and four).

The first US treaty with native peoples (the Treaty of Fort Pitt) was concluded in 1778 and created a defensive alliance between the new nation and the Delaware Indian people of Pennsylvania (Calloway, 2012:226). Subsequent treaties generally concluded episodes of open hostility between the American government (or the white settlers) and Indian peoples. Such episodes were usually struggles for control of land. The treaties concluding them usually included land cessions by the native peoples concerned (Nabokov, 1991:117121; Calloway, 2012:286-287). Often, these treaties would be followed by a new outbreak of hostilities as white settlers overflowed the boundaries previously agreed to. This would then be followed by new negotiations and agreements, further reducing Indian control over land. This period lasted until the US Congress ceased to negotiate further Indian treaties in 1871 on the one hand, and until open warfare ended with the "Battle" (or Massacre) of Wounded Knee in 1890, on the other.

During most of the nineteenth-century, US government policy toward the Indian population continued to include a mixture of, forced removal, open warfare, treaty-making, and confinement to reservations. This process was summed up by Buffalo Chief (Cheyenne), in 1867, "You [the US government representatives at the Medicine Lodge Treaty conference] give us presents, and then take our land. That produces war" (Nabokov, 1991:117).

The most notorious example of forced Indian removal was the result of the Treaty of New Echota in 1835. The agreement of some tribal leaders led to the so-called "Trail of Tears" of 1837-1838, the expulsion ("the drive-away" as some Indians called it, (Nabokov, 1991:149)) of the Cherokee from the south-eastern US to the Indian Territory, west of the Mississippi River, during which about a quarter of the population died of sickness or exposure (Brown, 1971:5-6; Calloway, 2012:291).3

Warfare on the Great Plains included a well-known series of wars against the Sioux nations (Dakota and Lakota). These began with "Little Crow's War" in 1862 and included the Battle of the Little Big Horn (or Greasy Grass). This was the so-called "Custer's Last Stand", in which an entire detachment of Federal troops, under the command of US general George Custer, were killed to a man, by a large mixed Indian force of Cheyenne and Sioux. This period of warfare on the plains finally ended in the "battle" at Wounded Knee, South Dakota in 1890. Conflict during this period was punctuated by treaty-making, notably by the Medicine Lodge Treaty with the Indians of the southern Plains in 1867 and the Treaty of Fort Laramie 1868, with the Sioux of the northern Plains (Calloway, 2012:345, 369-384; Brown, 1971:chapters three, six, 12, 18, 19).

In the south-western desert, warfare with the Apache Indians finally ended with the surrender of the great Chiricahua war chief Geronimo in 1886 (Calloway, 2012:351). However, this was after the US Congress ended the policy of treaty-making with the Indian nations and so no treaty with the Apache was ever signed. They were simply assigned to reservations (Brown, 1971:chapters nine, 17).

In each of these cases, Indians were isolated from the white majority of the American people and confined to their designated reservations. The native way of life was viewed as too different and endangered to expect it would long survive in direct competition with the larger, developing (white) American society (Nabokov, 1991:147-148; Calloway, 2012:286-288). Reservation life was viewed by many whites as the only hope for the preservation of the Indian people's traditional ways of life.

However, government policy shifted in the closing decades of the century. From the 1870s onward, the US Federal government gave up the policy of isolation of the various Indian nations on tribal reservations and moved toward the assimilation of Indian peoples into the culture, society and economy of the white majority.

One part of this effort involved the establishment of Indian boarding schools across the US. The purpose of these schools was to inculcate white culture and language in the younger generation of Indians and to create a generation of "Americanized" Indians. Away from their families and off the tribal reservations, Indian children were punished for the use of their mother tongue and learned the ways and means of finding their path through the world which the white man had created (Anderson, 2007:44-46, 51-53; Nabokov, 1991:213-217).4

This assimilation effort was supported by the passage of the Severalty Act (the Dawes Allotment Act) in 1887. The premise of this act was that the various Indian reservations should be broken up, communal land tenure would be ended, and the land distributed to individual small-holdings. This would encourage the Indian people dwelling there-in to take up settled farming in the manner of the whites, and to give up hunting, as their primary means of sustenance. This Act resulted in a drastic reduction in the amount of Indian-held land and the increased dependence of many Indian people, on government subsidies of various kinds, as promised in the various treaties (Calloway, 2012:420-423; Nabokov, 1991:232-237).

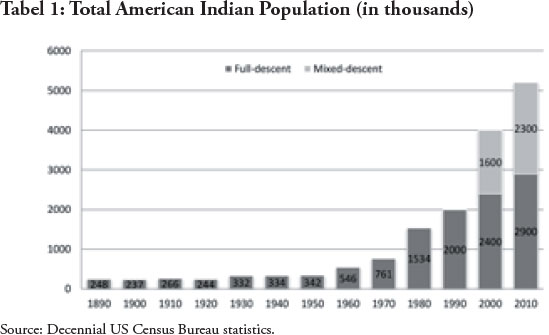

Under these pressures, the Indian population of the US steadily declined. The pre-Columbian native population of North America has been variously estimated at between two and ten million (or more) people. It reached its lowest point in 1900 when approximately 237 000 US inhabitants were identified as Indians (Nabokov, 1991:4).

During the twentieth century, this population was to experience a remarkable recovery.

The twentieth century

This, approximately fifty year long, process of assimilation culminated in the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. This act granted full US citizenship to that portion of the Indian population which had not already received it (through military service or as a result of the Dawes Act land allotments). However, as was the case for Black Americans living in the Jim Crow southern states, at this same time, federal promises of the right to vote could not always be put into practice as state governments often prevented the practical application of these rights (Calloway, 2012:446-447).

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, Indian reservation life was renewed in some ways; by the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. The purpose of this Act was to restore an element of self-government to the various reservation populations. It provided for the re-establishment of limited tribal self-government, to be conducted along European lines with written constitutions and elected councils, etc. (Calloway, 2012:487, 488491). Although this controversial measure was rejected by some (on the grounds that it was imposed by the government in Washington and that it was contrary to Indian tribal traditions of government), (Burnette & Koster, 2012:516-520), its acceptance by most tribes meant that control of most reservations was taken out of the hands of Washington-appointed (and often corrupt) Indian Bureau agents (Nabokov, 1991:324-329).

Following the Second World War, national Indian policy shifted again. Washington sought to "terminate" its official relations with the Indian nations and thus its formal role in Indian affairs. Various explanations have been given for this decision. The new commissioner of Indian affairs, in 1950, Dillon S. Myer, had supervised the detention camps which housed Japanese and Japanese-Americans, during the Second World War. These camps had been likened by many, to the German concentration camp system. Myer then came to see the Indian tribal reservations as a form of "concentration camp" which ought to be done away with (Nabokov, 1991:334). The reservations were seen, by others, as places which refused to adapt to (or rather conform to) the so-called "American Way of Life", which was under Cold War threat from the Soviet Union (Calloway, 2012:495-496). Either way, the reservation came to be seen as an anomaly in the American cultural landscape and as something to be done away with. Termination agreements were sought with tribes which were thought to be capable of sustaining themselves. Their reservations ceased to exist as independent legal entities and they were subsumed into the states in which they were located (Calloway, 2012:496-498; Nabokov, 1991:344-347).

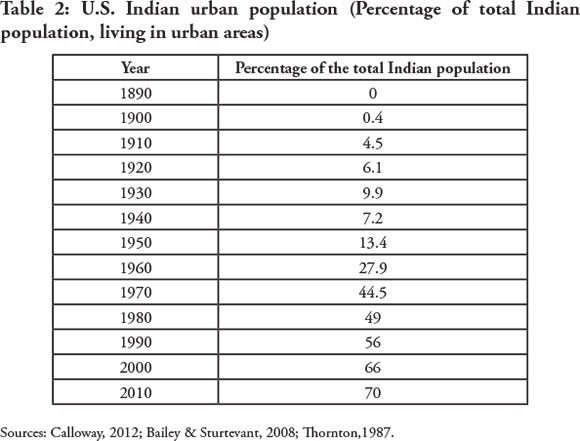

Related to this was the policy of voluntary re-location. Beginning in 1948, the US Federal government attempted to encourage the voluntary, subsidised transfer of as many American Indian people as possible, from their reservations to urban centres, primarily in the Western part of the US. In this way, the reservations would be gradually de-populated and their people would enter the mainstream of American urban life. Large numbers of Indians moved to cities such as St. Louis, Chicago and Denver, at least temporarily, in the pursuit of employment and a new way of life. However, some of these, disappointed with sub-standard housing conditions and the menial labour jobs available to unskilled workers from rural areas, eventually returned to their traditional reservation homes (Nabokov, 1991:348-351).

The New Activism of the 1960s and 1970s

The 1960s were a period of rejection of the status quo in Indian country as elsewhere.

In June of 1961, the American Indian Chicago Conference drew representatives from 90 tribes and bands. The result was a Declaration of Indian Purpose, sent to the new US president, John F Kennedy. This Declaration contained proposals for new legislation in areas such as economic development, health, welfare, housing, education, and law enforcement. The fundamental principle which underlay these proposals was that of self-determination for the American Indian peoples. The Indian peoples' way of life and culture was to be preserved from absorption by the dominant white American culture (Declaration of Indian Purpose, 1961:4).5

Later that same year, the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC) was established, under the leadership of, among others, Mel Thom, a young Paiute and Clyde Warrior (Ponca). The Council was born out of the frustration of youth delegates to the Chicago conference, over the perceived conservatism of the older representatives there. In its earliest period, the Council was particularly concerned to struggle alongside north-western tribes, to preserve fishing rights. It developed a particular interest in environmental issues from that point onward. The Council later supported Martin Luther King's Poor People's Campaign in 1968. Warrior, who is often compared to Malcolm X, participated in the March on Washington in 1963 and was the NIYC representative at Martin Luther King's anti-Viet Nam War march in Chicago in March of 1967 (Fluharty, 2011). Also in 1967, he presented an Indian view of poverty when, testifying before a Presidential Commission, he said that today the Indian peoples "are not free-free in the most basic sense of the word.. .we do not make choices. Our choices are made for us; we are the poor" (Warrior, 1967:529).

This younger generation of activists distrusted the older generation of tribal leaders, many of whom owed their positions to the structures established by the IRA of 1934 and to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in Washington. Condemned as "Uncle Tomahawks", this older generation of Indian leadership were often, as much seen to be the objects of confrontation, as were the Washington-based officials (Calloway, 2012:527).

The early effort to challenge the white power structure, by the NIYC, came in 1964. They supported the Nisqually and Puyallup Indians as the tribal leaders attempted to re-claim fishing rights along the Columbia and Nisqually Rivers, in the state of Washington, in the American north-west. These rights were guaranteed by the Medicine Creek Treaty of 1853. However, the state game and fishery officials of Washington sought to impose state laws on the tribal members. This challenge achieved a great deal of publicity (particularly as a result of the participation of the actor, Marlon Brando) through a series of "fish-ins" during which they defied state laws controlling fishing in these rivers (NIYC History; Nabokov, 1991:359, 362-363). Arrests followed, as did some prison sentences, but the local leaders also achieved some court victories (McCloud, 1991:362-366; Calloway, 2012:508). In the Boldt decision of 1974, the US District court upheld tribal fishing rights as originally established by treaty. Environmental damage had already reduced the practical effect of this decision, however.

In 1968, US President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Indian Civil Rights Act. This Act was passed in response to revelations of abuses by tribal governments, as raised in US Congressional hearings. The central elements of this Act were intended to apply most of the provisions of the US Bill of Rights of 1791, to American Indian tribe members. Because tribal governments had been recognized via treaties between the US federal government and tribal leaders, courts often held that Bill of Rights provisions did not apply on the reservations under tribal jurisdiction. The Act guaranteed that certain rights as freedom of speech of the press, and of assembly, the right of the accused to be represented by an attorney in criminal cases, protection against "cruel and unusual punishment", and most fundamentally, the right to "equal protection under the law" all would be available to those on, as well as off, the reservation (Northwest Justice Project, 2012:1). The effect of the Act was later somewhat diluted by the US Supreme Court decision Santa Clara Pueblo vs. Martinez of 1978, which limited US Federal court oversight of tribal courts.6

Nineteen sixty-eight also marked the beginning of the most militant Indian Rights Organisation, the American Indian Movement (AIM), led by Russell Means (Ogallala Lakota) and Dennis Banks (Anishinaabe). Advocates of "Red Power", Means and Banks, along with other AIM leaders such as Vernon and Clyde Bellecourt (Chippewa) became the most generally well known American Indian activist leaders of the 1960s and 1970s, as they borrowed various strategies from the Black Power Movement (Bellecourt, 1973:372376). In particular, AIM adopted the Black Panther Party tactic of street patrols. In radio equipped cars, they shadowed police vehicles in Indian urban neighbourhoods. They then monitored the treatment of Native youths arrested by the police, in an effort to curb incidents of excessive force in such arrests.

The 1960s ended with what was probably the most dramatic demonstration of the new Indian activist trend, the illegal occupation of the former federal prison on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay (Fortunate Eagle, 1991:367370). This occupation lasted from November 1969 until the removal of the last protestors, by US marshals, in June 1971. During that period, a changing series of both Indian leaders and participants, and government negotiators were involved. During the occupation, the group on the island issued a "Proclamation to the Great White Father and to All 'His' People" (Calloway, 2012:532).

The next decade included several note-worthy demonstrations and other public activities, all intended to bring the needs and demands of the native community before the larger American public.

In 1970, in November, on Thanksgiving Day, at the site of the supposed "first thanksgiving", Plymouth, Massachusetts, Indian activists declared a "National Day of Mourning".

In the autumn of 1972, leaders organised a "Trail of Broken Treaties" to bring together native participants from different parts of the US, to converge on the national capital in Washington. This march led to the unplanned, six-day occupation of the headquarters building of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the presentation of the planned list of demands, the "Twenty Points". In this document, AIM and other activists called for the abolition of the BIA, the review of all treaties, greater protection for Indian culture and a renewed commitment by the Federal government to the restoration of Indian community life, socially and economically (Calloway, 2012:548).

In 1973, the Ogallala Sioux (Lakota) nation declared its independence from the US in an attempt to re-assert national sovereignty. Before that year was out, the US government was confronted with the most direct challenge to its authority since the end of the military period of US-Indian relations in 1890. Traditional leaders engaged in a challenge to the administration of tribal council president, Richard Wilson. They enlisted the support of AIM who arrived at the Pine Ridge reservation along with about two hundred supporters. They met a force of US federal marshals and FBI agents at Wounded Knee. The resultant stand-off lasted more than two months. Enormous press coverage was generated, but at the cost of several wounded, and two dead Indian activists (Calloway, 2012:550-551; Crow Dog, 1991:573-575). The end of the siege was finally negotiated after the intervention of a US Senator, and the disputed Wilson tribal administration was later brought to an end (Nabokov, 1991:362).

Issues of women's liberation entered the Indian rights movement as they did the Black freedom movement and the anti-war movement of the same period. In 1974, Women of All Red Nations (WARN) was established. This was partly in response to a degree of marginalisation experienced by Indian women who were part of AIM. Leaders such as Janet McCloud were involved in issues from the north-west Indian fishing rights campaign to the renewal of native spirituality (Trahant, 1999). They took up several issues of particular interest to Indian women, including the sterilisations of native women by the Indian Health Service. This practice was a hold-over from the much earlier era of eugenics activity, but did not entirely end on the reservations, until the 1970s (Johansen, 2011).

Conclusion

One might ask, how did it happen that this American Indian movement for civil rights arose at the same time as the American Black Freedom and other similar movements? It is to be expected that a certain synergy developed amongst the many activist movements of that era, during the 1960s and 1970s in the US. These different movements learned from one another, borrowing tactics and taking advantage of the increasing opportunities for mutual support. The exposure offered by electronic media such as television, made the struggles of women, black Americans and anti-war activists common knowledge in Indian country and beyond. However, American Indian peoples endured unique pressures in post-war America. The disintegration of tribal and reservation life generated first by land allotment, and then by tribal termination, caused the rapid deterioration of many tribal bonds. This was added to the larger social pressure of American society, from which Native Americans were not immune or even isolated. Thus, the question is not, why there was an Indian civil rights struggle in the 1960s and 1970s, but why did it take so long to surface?

The American Indian Civil Rights movement and its historical background are of some relevance to grade 11 learners and their teachers. The study of race and racist thinking in the 19th century may be opened up by an examination of some aspects of the treatment ofAmerican native peoples by the US Federal government. This would be worthy of a further study.

However, this movement has most direct relevance to those in Grade 12 and their instructors. The CAPS document particularly points to the Black Freedom Movement, the Women's movement and the peace movements as the specific, examinable sub-topics under Civil Society Protest.

The American Indian movement will provide the classroom teacher with useful points of comparison to the Black struggle for civil rights. As has been seen, there are some direct points of contact between these movements. Some individual Indian leaders sought to participate, as Indian leaders, in the larger struggles of the 1960s and 1970s, as led by such figures as Martin Luther King, Jr. Others consciously copied the tactics of groups like the Black Panthers. Indian women, like African American women at the same time, began to wrestle with their dual identities as women, and as members of a minority group within a larger, discriminatory society.

It is also worthwhile to address the question of the disparity of response, by the larger American society toward the black freedom struggle, and the seemingly parallel efforts of Native Americans. For several years, the white majority of the US was caught up by the black struggle for social equality, with millions riveted by the images on the nightly television news reports. The Indian Civil Rights Movement never received the support of such a mass audience, however.

This difference may flow from a number of sources. Perhaps the Indian movement's lack of charismatic leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr. or Malcolm X helped to diminish its public profile. Clyde Warrior, for instance, died of alcohol abuse while still in his twenties. Some others, such as Russell Means, moved off the national stage into tribal politics at least for a time. Of course this raises the question, did the lack of media attention itself prevent the rise of such a leader to public prominence? Were such leaders present, but ignored by the mass media; what came first, the media attention, or the leader?

Then there was always a great disparity of numbers between the two campaigns. During the 1960s, black Americans were approximately 10 percent of the total US population. Most white Americans came into contact with some black people, on a daily basis. The 1963 March on Washington numbered nearly a quarter of a million participants (Kenworthy, 1963:12) while the Trail of Broken Treaties caravan counted only about 500 participants in Washington, in 1972. As has been seen, the American Indian population represented less than one half of one percent during the 1960s. Relatively few whites ever saw an American Indian person beyond a few western states (or apart from a movie theatre, or on television, in a cowboy western). Did the black American liberation struggle represent the efforts of a people who seemed more "real" and known to the majority of Americans, while the Indians seemed more distant and perhaps "fictional"?

Finally, were the two movements different in a way which made the black liberation struggle seem less threatening? At the beginning of their struggle, African American leaders recognised their status as the directors of the movement of a definite minority within American society. They sought cooperation and support, by appealing to the collective conscience of the white majority. This was to change for many white Americans, after the violence of the late 1960s. However, many Indian leaders tended to be more confrontational, from earlier on. They may have been drawing on a centuries' long collective memory of armed struggle by Indian polities and sovereignties against white power structures in North America. As one Indian leader said, "Indian people are nations, not minorities" (Calloway, 2012:640). In their approach to the dominant American society, they insisted on being recognised as such.

References

American Indian Chicago Conference 1961. "Declaration of Indian Purpose". Available at http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED030518.pdf. Accessed on 10 November 2014. [ Links ]

Anderson, L 2007. Carlisle vs. Army. New York: Random House. [ Links ]

Bailey, GA and Sturtevant, WC 2008. Indians in contemporary society. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. [ Links ]

Bellecourt, V 1973. "Birth of AIM". In: P Nabokov, 1991. Native American testimony: A Chronicle of Native-White relations from prophesy to the present, 1492-1992. New York: Viking. [ Links ]

Brown, D 1971. Bury my heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian history of the American west. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [ Links ]

Burnette, R & Koster, J 1974. "A blueprint for elected tyranny". The road to Wounded Knee. New York: Bantam Books. In: CG Calloway, 2012. First peoples: A documentary survey of American Indian history. Boston, New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. [ Links ]

Calloway, CG 2012. First peoples: A documentary survey of American Indian history. Boston, New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. [ Links ]

Childers, EB 1882. "Responsive and resistant students". In: P Nabokov, 1991. Native American testimony: A chronicle of Native-White relations from prophesy to the present, 1492- 1992. New York: Viking. [ Links ]

Crow Dog, M 1991. "I would rather have my baby at Wounded Knee" (with Richard Erdoes) Lakota Woman. New York: Harper Perennial. In: CG Calloway, 2012. First peoples: A documentary survey of American Indian history. Boston, New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. [ Links ]

Deloria, Jr, V 1991. "Forward". In: P Nabokov, 1991. Native American testimony: A Chronicle of Native-White relations from prophesy to the present, 1492-1992. New York: Viking. [ Links ]

Fluharty, S 2011. "Warrior, Clyde", ABC-Clio History and the Headlines. Available at http://www.historyandtheheadlines.abc-clio.com/ContentPages/ContentPage.aspxPentryId=1171993¤tSection=1161468. Accessed on 21 September 2014. [ Links ]

Fortunate Eagle, A (Red Lake Chippewa) 1991. "Invading Alcatraz". In: P Nabokov, 1991. Native American testimony: A chronicle of Native-White relations from prophesy to the present, 1492-1992. New York: Viking. [ Links ]

Iron Shell (Brule Sioux) 1868. "We want you to take away the forts from the country'. In: CG Calloway, 2012. First peoples: A documentary survey of American Indian history. Boston, New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. [ Links ]

Johansen, BE 2011. "Women of All Red Nations", ABC-Clio History and the Headlines Available at http://www.historyandtheheadlines.abc-clio.com/ContentPages/ContentPage.aspx?entryId=1172002. Accessed on 17 October 2014. [ Links ]

Kenworthy, EW 1963. "200, 000 March for civil rights in orderly Washington rally; President sees gain for Negro", The New York Times, August 29, 1963. In: Reporting civil rights: Part two, American journalism 1963-1973. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Library of America. [ Links ]

Lone, W 1972. "Responsive and resistant students". In: P Nabokov, 1991. Native American testimony: A chronicle of Native-White relations from prophesy to the present, 14921992. New York: Viking. [ Links ]

Mankiller, W 1993. "Returning the balance" (with Michael Wallis), Mankiller: A chief and her people. New York: St. Martin's Press. In: CG Calloway, 2012. First peoples: A documentary survey of American Indian history. Boston, New York: Bedford/ St. Martin's. [ Links ]

McCloud, L (Tulalip) 1971. "The new Indian wars". In: P Nabokov, 1991. Native American testimony: A chronicle of Native-White relations from prophesy to the present, 14921992. New York: Viking. [ Links ]

Nabokov, P 1991. Native American testimony: A chronicle of Native-White relations from prophesy to the present, 1492- 1992. New York: Viking. [ Links ]

National Indian Youth Council. "NIYC History". Available at: http://www.niyc-alb.org/history.htm. Accessed on 10 November 2014. [ Links ]

Northwest Justice Project 2012. "Indian Civil Rights Act". Available at http://www.washingtonlawhelp.org/files/C9D2EA3F-0350-D9AF-ACAE-BF37E9BC9FFA/attachments/3928DFFE-A03E-7661-F42B-BDFE2C910E91/9202en.pdf. Accessed 12 September 2014. [ Links ]

One Horn (Miniconjou) 1868. "This is our land, and yet you blame us for fighting for it". In: CG Calloway, 2012. First peoples: A documentary survey of American Indian history. Boston, New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. [ Links ]

Sale, K 1991. The conquest of paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columbian exchange. London: Hodder & Stoughton. [ Links ]

Thornton, R 1987. American Indian holocaust and survival: A population history since 1492. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. [ Links ]

Trahant, M 1999. "The center of everything-native leader Janet McCloud..." The Seattle Times, July 4, 1999. Available at http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19990704&slug=2969841. Accessed on 20 November 2014. [ Links ]

Warrior, C 1967. "We are not free", The president's National Advisory Commission on rural poverty. In: CG Calloway, 2012. First peoples: A documentary survey of American Indian history. Boston, New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. [ Links ]

1 I would like to thank the Gilder-Lehrman Institute of New York City, for selection as one of the participants in the seminar, "Native American History", held at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire (USA), during August 2014. Professor Colin G Calloway, of the College, conducted this seminar and authored the main seminar text. Maura Wynne, the Assistant Principal, Social Studies, at Sheepshead Bay (NY) High School, was the seminar master teacher. Mrs Trish Godlonton, the deputy administrator of Michael Mount Waldorf School has provided me with an academic home, and the opportunity to participate in the SASHT conference at the University of the Witwatersrand, October 2014, where the original version of this paper was first presented.

2 The use of the term "Indian" is not without controversy. In some parts of the United States it is being supplanted by the term "Native American". However, particularly in the American West, it is still the accepted term amongst indigenous people themselves (Calloway, 2012: 11).

3 The Cherokee were one of the so-called "Five Civilized Tribes" of the south-eastern US. They were called this because of their success in adopting European agricultural practices and other adaptations to white culture. Despite this, the US state of Georgia insisted upon, and got, their expulsion to the Indian Territory, west of the Mississippi River. Their overland trek, to this new home, resulted in the deaths of up to 25% of the tribal population (Brown, 1971:7).

4 One Indian student account records how "We were told never to talk Indian and if caught, we got a strapping with a leather belt" (Lone Wolf [Blackfoot], 1972:218). On the other hand, the father of one student at the famous Carlisle Indian School for boarders, was quoted as saying "Here are people trying to teach you. You must try to learn and when you come back home your people will be glad to see you and what you learn will be a benefit to them" (EB Childers, Creek, 1882:219).

5 It is worth noting that the Declaration begins with a "pledge" of loyalty to the American democratic form of government and a rejection of "any alien form of government... (or) ideology". This is clearly a Cold War era statement of the rejection of Soviet communism (Declaration of Indian Purpose, 1961: inside front cover).

6 Gale Encyclopedia of US History 2006, "Indian Civil Rights Act" (available at http://www.answers.com/topic/indian-civil-rights-act, as accessed on 20 November 2014).