Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Yesterday and Today

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9003

versão impressa ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T no.11 Vanderbijlpark Jan. 2014

ARTICLES

Writing and contextualising local history. A historical narrative of the Wellington Horticultural Society (Coloured)

Francois J Cleophas

Department of Sport Science, Stellenbosch University fcleophas@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to enhance local history as a focus area in a Higher Education (HE) teaching context. This article documenteda case study of thepractice of flower growing as a recreational-competitive activity. A historical narrative was thus constructed around the Wellington Horticulture Society (Coloured), henceforth referred to as the (WHS). The founding of the WHS coincided with the emergence of cultural organisations in Wellington. Furthermore, it was part of a social development, known as garden culture. By using documentary evidence, previous research material and an oral historical account, a narrative of the WHS was created, emphasising aspects, such as competition, family history and garden culture. This research identified social and political dilemmas associated with the WHS.

Keywords: Competition; Family; Historical thinking; Gardern Culture; Local history.

Introductiory remarks

This research used local context for developing undergraduate material for course work in history at a Higher Education (HE) level. Local history (LH), using themes in recreation, remains an undervalued area of teaching. However by utilising LH in the curriculum, an opportunity is created where students can: "... relate to past trends, inclusive of a local community experience within a personal worldview of ideas and beliefs..." (Van Eeden, 2013:37). It is possible for students to construct a LH narrative that is a "good story" that (a) is built on facts, (b) convey meaning to those facts, and (c) use facts as evidence that supports a narrative. A "good story" is a narrative created with connections between facts that turn incoherent chronicles into meanigful discourses (Hammarlund, 2012:119). A research question was thus devised: How can narrative writing assist undergaduate students develop historical thinking? Historical thinking concepts is described in terms of The Canadian Benchmarks of Historical Thinking Project conducted by the University of British Columbia's Centre for the Study of Historical Consciousness. This project categorised historical thinking into six concepts: (a) historical significance, (b) evidence, (c) continuity and change, (d) cause and consequence, (e) historical perspectives, and (f) moral dimension (Peck & Seixas, 2008:1017, 1024). These concepts will be clarified in the conclusion, using examples from the narrative.The findings of this investigation will be included in a Sport History module, SW 362 at the Stellenbosch University as a LH assignment (See Appendix). The assignment will be assessed by means of a rubric adapted from the work of Van Eeden (2013:46).

Research methodology

During the 19th and 20th centuries, the idea that the nuclear, monogamous and patriarchal family structure was the basic cell of society was shared throughout Europe (Martin-Fugier & Perrot, 1990:100). This was evident in the WHS and Reggie Maurice (2013) comments: "The WHS members were involved because their parents were [and] ... there were always teenagers taking part in the activities" (R Maurice, 16 November 2013). Therefore, this research foregrounded family's involvement in the WHS. Attention was therefore directed to Albert Maurice, Daniel Retief and especially the Small Family, since they impacted on the evolution of the WHS and were prominent in the social life of early 20th century Wellington.

A qualitative research design was used that relied on retrieving primary and secondary documents (archival material, books, electronic communication, newspaper reports and oral testimonies) for evidence. The findings were presented in thematic form that does not conform to the commonly used chronological presentation often found in historical works. An oral testimony of Reggie Maurice, son of a founder member of the WHS, was pivotal in the data-collection process.

Superficial "racial" categories (African, Coloured and White) were presented with first letter capitals. The reasoning behind this include a response to the gradual normalisation of South African society in the post-Apartheid period and partly in recognition of the WHS that identified itself as Coloured (Adhikari, 2006:xv). In the following sections, social-political developments that influenced the WHS during the early 20th century will be presented. Reference will be made to the impact of club culture and competiveness on early 20th century Cape society and garden culture as a distinct middle class value. Next, the early 20th century political organisation, the African Political (later People's) Organisation (APO), will be overviewed. This is followed by a historical overview of the WHS and it's social features. Albert Maurice and the Small family will then be placed under microscopic investigation as regards their contribution to the WHS. Finally, the study will be concluded by answering to the six concepts of historical thinking as outlined in the The Canadian Benchmarks of Historical Thinking Project.

Background of events leading to the WHS

The post - South African War (1899-1902) period was characterised by increasing statutory racism against Coloured people. For example, in 1905, the Cape Parliament promulgated the School Board Act, which introduced compulsory education for White children only (Adhikari, 1993:21). At the same time, White privilege encouraged racial exclusivity within Coloured communities by heightening their group consciousness. This group consciousness became a central feature of organised cultural organisations (Cleophas & Van der Merwe, 2011:124-140).

According to the historian, Mohammed Adhikari, clubs and societies in Coloured communities during the early 20th century, expressed their identity by taking pride in their proximity to Western culture (Adhikari, 2002:32). This was done to gain respectability, and what was termed "civilisation" in society. To be respectable and civilised meant being morally upright, financially independent, industrious, honest and exhibit self-control (Badham, 1985:79). For many early 20th century Coloured leaders, respectability and civilsation also meant "high culture", which was a determining factor for distinguishing between "civilised" and "barbarous" peoples. They viewed the ability to be efficient in esoteric procedures and constituting the arts to exacting standards, as proof of their ability of reaching "high culture" (Adhikari, 1993:166). In elite circles in England, a well-kept garden that was cherished by it's owner, provided requisite means for "high culture" (Molyneux, 1890:Introduction).

Many early 20th century politicians promoted these values, along with what they called, sensible recreation (Bickford-Smith, Van Heyningen & Worden,1999:43). One sensible recreation activity was flower growing in well-kept gardens. Flowers played an important part in the social lives of early 20th century Wellingtonians. The mission schools in Wellington (Pauw Gedenk Dutch Reformed, St Albans English Church and the African Methodist Episcopal Mission Schools) organised athletic competitions amongst themselves where the winners received flowers (R Maurice, 16 November 2013).

Sensible recreation, in the form of gardening, was based on three notions that formed part of English civilisation values. The first notion refers to a hallmark that hard work brings success. Therefore, a newspaper columnist could write (Clarion, 1919b:16):

No matter how large or small or how barren and bare your piece of ground may be, by quiet persistence and industry, you may quickly transform it into idealistic floral palaces. Even the stoep, with the aid of a few old tins and the manufacture of a flower stand or two, can be turned into a veritable garden of Eden.

The planting of chrysanthemums appealed to the petty bourgeoisie because of the immense effort required to grow them. FW Allerton (1949:v,xi), a scientific expert on chrysanthemums stated that it was only after several false starts that this flower became established in England in 1790. Reggie Maurice recalled that chrysanthemums plants grew well when individual attention was given: "You can't just plonk it in a tin... what I remember they had rows of paraffin tins and the plants were nurtured individually to get a champion bloom. You couldn't get a mosquito to come and milk the bloom." (R Maurice, 16 November 2013).

The second notion was that of communal assistance to "one's own kind". This is evident from the same columnist's words: "A great number of my readers will be unable to go in for all the varieties of seeds that I may enumerate from time to time, so a good plan is for several friends to work in conjunction" (Clarion, 1919c:10).

The third notion was that, gardening had to fit in with the age of science and modernity. Therefore, the columnist suggessted that the gardener studies his plants so effectively that he would make every plant a winner (Clarion, 1919d:10). Reggie Maurice stated that chrysanthemum growers in Wellington had reached the position where they could hybridise their plants (R Maurice, 16 November 2013). Sensible recreation also centred on family life, which was the basis of social life at the Cape (Van der Ross, 2007:28).

From the late 19th century onwards, more mission school educated Coloured men displayed an active interest in politics, both at municipal and legislative levels (Van der Ross, 1975:6). Many of them registered as voters. When this right was granted in 1853, it was restricted to British subject males, over the age of 21 who earned at least £50 a year, or who owned fixed property worth at least £25 (Van der Ross, 1986:9). The Cape Parliament, however, feared the increasing number of Africans who became eligible voters and responded by raising the franchise qualifications, first in 1887 then in 1892, for "uncivilised" Africans and poor and illiterate Coloureds and Whites (Thompson, 1949:7). Against this backdrop the WHS organised a competition in 1917 in Wellington, Cape Province for the social upliftment of the Coloureds.

Social-political developments in Wellington during the early 20th century

The early 20th century Coloured community in the town of Wellington were largely middle class and led reasonably comfortable lives. Many of them had franchise qualifications. The town was also an educational centre from where a few 20th century public personalities could trace their ancestry. These include Hadjie Abdurahman, the father of the African Political Organisation (APO) president, Dr Abdullah Abdurahman, "... the pioneer of modern education for the Cape Moslems" (APO, 1920a:11; Clarion, 1920:10). Another public figure with historical connections to Wellington was the non-racial sport activist, Dennis Brutus, whose father, Francis, was an active member of the Wellington branch of the APO in 1909 (APO, 1909a:2, 1909b:2, 1912b:5; T Brutus, 9 September 2013).

In 1920, the local APO branch proposed that one of its members, Abe Desmore, who was later elected president of the Negro Education Club at Columbia University and published a book on the Cape Corps, be nominated to stand as candidate in the provincial elections of 1920 (APO, 1920b:9; Sun, 1935a:6). This intellectual capital was accompanied by economic and social prosperity brought about largely by the opening of the Cape Town - Wellington railway line in 1863 (Cape of Good Hope, 1862:8). A few business-minded Coloured people opened a co-operative butchery in 1911 where the share prices doubled by 1915 (APO, 1915a:3). In 1916, a pork factory was opened (Serfontein, 1998:22). According to Reggie Maurice, who grew up in Wellington in the 1930s, the presence of the brandy distillery

(Sedgwick and Company), Cape Government Railways, Coaton and Louw Tanning Company, Jordan shoe factory, Mrs Ball's Chutney and various government departments, meant there were employed industrial workers who developed into a skilled Coloured middle class (R Maurice, 16 November 2013). This class had social confidence and tried to resist paternalistic attitudes displayed by White farmers towards Coloured labourers. It was common for White farmers to hold a religious service for Coloured servants every Sunday, be it by the farmer, his wife or daughter (Paarl Post, 1921b:6). This middle class also had more free time available for leisure pursuits unlike rural peasants who were often too tired after a day's work on the farm (Paarl Post, 1916:2).

Some Wellington leaders started clubs and societies around notions of respectability, class and racial identity. These clubs and societies distanced themselves from Africans and lower class Coloureds who were regular visitors in upper Pentz Street, commonly known as Kantienstraat (Shebeen Street). However, when these club leaders implemented an upliftment theme, they were aware that they were not allowed to ". go too far . for a club by becoming too respectable may cease to exist (Rigby & Russel, 1908:23). Therefore, political leaders, such as Desmore, encouraged his listeners to follow a path of upliftment and pursue personal advancement rather than direct political confrontation (Clarion, 1919g:7).

Desmore emphasised industrial rather than agricultural development. In the Western Cape, agricultural development was controlled by White farmers. Therefore, the Coloured elite in Stellenbosch organised themselves into the Stellenbosch (Coloured) Horticultural and Industrial Society (Sun, 1935b:1; 1935c:2). Hence, Coloured intellectuals found themselves being treated ambivalently by White society. In contrast to the negative stereotypical attitude displayed towards African people by Whites, Coloured people, who were perceived as "civilised", were treated with a measure of empathy (Gerwel, 1983:4).

False political promises were made to Coloureds by White leaders about placing them on an equality with Europeans (De Burger, 1925:7). Coloured leaders therefore advocated social upliftment in order to prove themselves worthy of equality with Whites. Many of these leaders saw clubs, competition and culture as the best vehicles for this upliftment theme. If gardening was to become part of this upliftment theme, it had to be made part of competition culture, prevalent in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In England, cottage gardens were often considered an unconscious display of the gardeners' ability, which was tested at the village show (Bird & Lloyd, 1990:13).

Moving from floral shows to horticultural societies

The period mid-19th to early 20th century in the Cape Colony and Cape Province was characterised by an increasing emphasis on a theme of advancing civilisation through societies or clubs. Therefore, a Cape of Good Hope Agricultural Society (CGHAS) was established in 1831 (Cape of Good Hope Agricultural Society, 1853:1). When social clubs and societies such as the CGHAS were initially formed, they had certain primary functions, of which two are of interest to this study: to codify rules and to organise competition (Maclean, 2013:1691). By 1913 and after the First World War, there were physical training and choir competitions organised by the education department and church agencies for mission schools (APO, 1913c:4; 1913d:4; 1921:11). Competitions allowed individuals from marginalised communities to attain success and experience feelings of achievement. In 1938 for example, A. Moses, won the champion bloom division and eight other divisions in the WHS competition (Sun, 1938b:4). The WHS also pursued 'high culture' and John Abrahamse, a Wellington school principal, stated that the WHS must " ... cultivate an aesthetic sense in our people ..." (Sun, 1932:4). The petty bourgeoisie who pursued this "high culture" realised it required effort, and the Sun reporter remarked in 1933: "When one considers the immense amount of preparation and detail such a function demands, one cannot help but praise the laudable efforts of this small band of untiring workers who strive for the cultural upliftment of their kin" (Sun, 1933:5).

Hard work was considered worthwhile by Coloured leaders because it brought praise from influential individuals. When the Premier Poultry and Horticultural Society (Coloured) held its ninth annual competition in Paarl, the resident magistrate and the Master of Ceremonies showered adulations on the participants. The magistrate proclaimed it was the best show he had ever seen, while the Master of Ceremonies went to great lengths lamenting on how Coloured people are on the same cultural level as Whites (Sun, 1937:11).

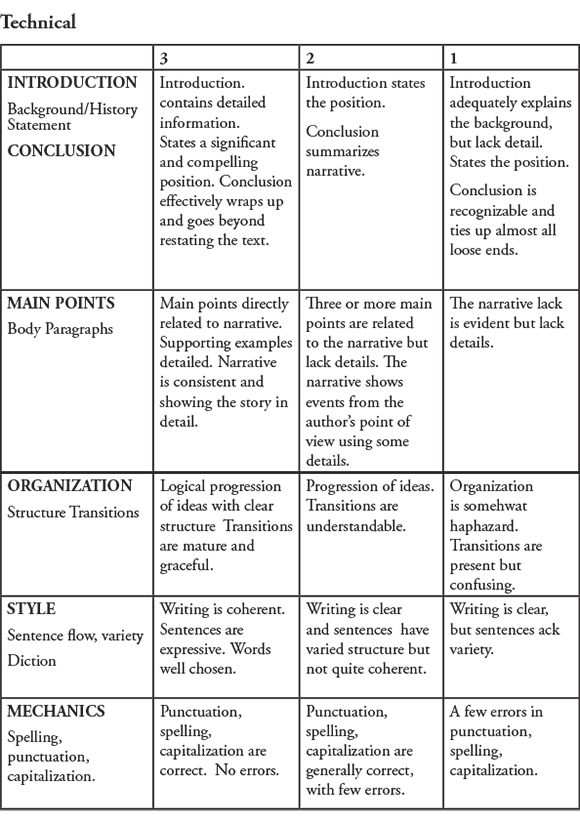

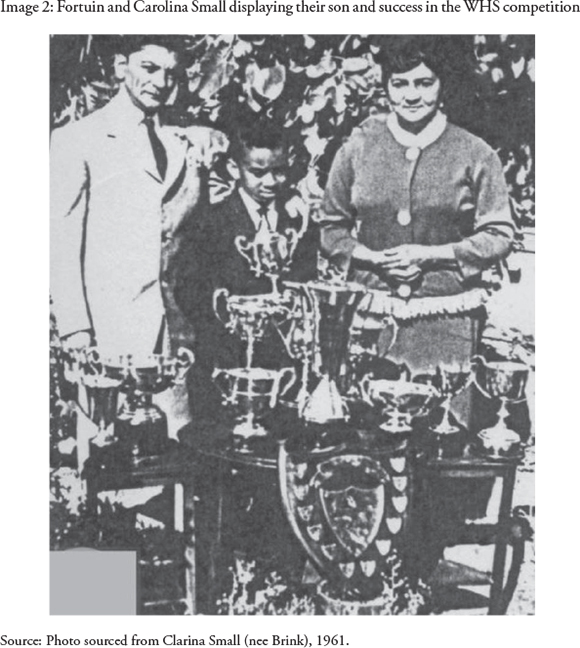

RJ du Toit, a United Party parliamentarian, speaking in his capacity as president of the Pinelands Horticultural Society (PHS), demonstrated how horticultural societies teach people to love that which is beautiful (Sun, 1938a:6). Coloured political leaders supported this idea of "beautiful living" and J Brink, an APO branch official, stated that the aim of the APO was to uplift the Coloured race (APO, 1914b:4). A further trait of "high culture" was public dress, an aspect that remained part of the WHS's throughout the 20th century. (see Images 1 and 2 below).

Role of Daniel (Dan) Retief

Social clubs had influential individuals as patrons or honorary presidents and Senator Daniel (Dan) Retief was elected as president of the WHS in 1917 (Wellington Horticultural Society, 1997:3). A brief biographical sketch of Dan Retief will show how the virtues of "high culture" often transcended some of the artificial racial boundaries between Afrikaner and Coloured identity where both groups bought into a post-Victorian practice called garden culture. Daniel Retief (born on 21 March 1861 and deceased on 20 May 1944) was a prominent public figure in Cape society. He was educated at the South African College in Cape Town, owned farmlands in Wellington and Van Rhynsdorp, was a member of the Provincial Council, and a founder member, and later chairman, of the South African Dry Fruit Company. He also had shares in the Wellington Fruit Growers Limited, South African Dried Fruit Company and Ko-operatiewe Wynbouers Vereniging (Retief, 1988:156; Western Cape Archives and Records Services, MOOC 6/9/10930/92313). Socially, he belonged to the upper echelons of Cape society and was recognised by the ruling elite as an achiever (Donaldson, 1916:283).

Many Coloured clubs and societies owed their existence to sympathetic White liberal minded individuals, such as Sir David Harris and Cecil John Rhodes (Odendaal, 2003:78-79). In Wellington, Retief represented this trend and Reggie Maurice remembered him as follows (R Maurice, 16 November 2013):

There was a chap in Wellington who was the only sponsor of this, he was a senator of the United Party, Dan Retief... he had a wine farm... I can remember a large patch of chrysanthemums on his farm... my father and I used to go there now and again... my father didn't drink so you saw one man with a cup of tea ... but there was an amicable relationship between them . he presented one or two trophies to the WHS.

Despite the historical prominence of his family in Afrikaner society, he was sympathetic towards some social causes in the Coloured community. In 1917 he was instrumental in convincing the Wellington Town Council to accept the offer of Rev Andrew Murray, from the Dutch Reformed Mission Church (Coloured), to purchase Church property in exchange for developing some tennis courts (Western Cape Archives and Records Services, 1917:198). Retief also contributed to the promotion of gardening societies. He opened the Wellington Tuinbouw Genootskap (Wellington Gardening Society) display in 1917, and welcomed the Cape Town mayor, Harry Hands to the competition on Wednesday 25th April in the Wellington Town Hall (De Burger, 1917a:2; Paarl Post, 1917a:6).

Gardening society members were gardeners or florists whose interest in plants was for decorative rather than culinary or medicinal value. In England gardeners formed specialist societies and held competitions, often at public houses that included "merry festivities", hence the term, "florist feasts" (Bird & Lloyd, 1990:14). A similar tend developed at the Cape where florist shows reflected the "merry activities". When the Groot Drakenstein floral show was held in Franschoek (1911), it was loaded with British symbols such as Maypole dancing, military regiment bands and sanctified by a minister of religion (Paarl Post, 1911c:3). The analysis will now show how these "florist feasts" evolved into socities and became avenues for a petty bourgeoisie class to claim cultural space for themselves.

Garden culture as a distinct middle class value

From the mid-19th century, middle class homes in England were designed exclusively for domestic living and the idea spread to the colonies. Comfortable homes with gardens were an important part of this development (Hall, 1990:72). A visitor to Wellington reported that most Coloured inhabitants there own their own comfortable homes and a few even luxuious (S.A. Spectator, 1902:2). These homeowners were comparable to the 19th century cottage gentry who maintained gardens, not because of the necessity to grow vegetables and fruit, but to adopt a comfortable lifestyle that displayed opulence.

This was in contrast to the peasants who lived a subsistence lifestyle, and who had little interest in flowers and preferred meat and, when he could get to it, vegetables (Bird & Lloyd, 1990:9,10). The gardens of rural peasants in the Cape Colony, such as in Constantia, supplyed basic food needs and did not display opulence. A writer with historical roots in Constantia, Richard van der Ross, wrote that, in the early 20th century, this area was one where children took part in keeping the vegetable garden, in tending the chickens, collecting eggs, feeding the donkey and pigs, collecting cow dung for smearing the floors (Van der Ross, 2008:29,46). Elsewhere it was reported that poorer Coloured folk, sell flowers and heath in Cape Town and the Karoo (Cape Register, 1898:21; 1899:27). The WHS members did not grow flowers for these purposes, but rather to display their middle class status. Reggie Maurice commented (R Maurice, 16 November 2013):

There was a divide [amongst Wellington's Coloured community] but it was not an engineered one, it was one, which was common to every group ... [therefore] the WHS was a town activity, an urban activity. They would not grow [chrysanthemums] on the farms because they would not have the money, fertilizers and time.

In 1907 a Cape philantropist, Richard Stuttaford, was introduced to the Garden City Association of Great Britain whose principles were based on Gardern Cities of tommorrow, the work of the British urban planner, Ebenezer Howard. Ten years later, a garden city was established in Welwyn, England which became a model for Richard Stuttaford's future vision for Cape gardens (Garden Cities, 1972:11-12). It was in this climate of environmental conscioiusness that organised politics was introduced and operated in Wellington.

Early 20th century political organisation in Wellington

The APO started a Wellington branch in March 1909 and although men controlled clubs and societies, women gradually entered public life and in 1914 the Wellington branch of the APO suggested the founding of a women's branch for the 25 females who wanted to join the organisation (APO, 1909d:3; 1914c:11). Although APO membership in Wellington was inconsistent and paid up members decreased from 125 to 25 between 1909 and 1913, the organisation impacted on social life in the Coloured community and controlled most of the organised social activities of the elite (APO, 1913a:3). The Wellington branch and its neighbours, Paarl and Worcester, were made up of a generation of politically minded men with ideas that differed from previous generations. These ideas included the channelling of community efforts and political differences through clubs and societies. When the Wellington branch hosted a meeting with neighbouring branches in 1909, a speaker advised those in attendance that there was a need to submerge petty differences which may exist among them. It was not reported what he meant by "petty differences" but they were impatient with the political "lethargy" of the previous generation that caused a "slow growth of civilisation and education amongst Coloured people" (APO, 1909d:2,3). Members of the Wellington branch were politically conservative and some supported the racist National Party (APO, 1915b:5). Some emphasised that Coloured people were closely associated with White history and distanced themselves from indigenous culture. One member, Francis Brutus, argued that the ". history of the education of children from European descent dated from 1652 whilst that of the Coloured race only goes as far back as the dawn of the 19th century" (APO, 1909b:2). Through this assimilationist approach, the APO secured facilities for sport and recreation from the Wellington Council. (APO, 1909c:3). By 1917 there were a considerable number of Coloureds in Wellington who qualified for the voters' roll. It was from this group that the membership of the WHS (Coloured) came, as will be shown in the following sections.

Historical background ofthe Wellington Horticultural Society (Coloured)

A Wellington Tuinbouw Genootschap (WTG) (Wellington Horticultural Society), made up of Whites, celebrated its sixth annual spring show in 1917, meaning it organised it's first competition in 1911 as a "floral feast" or "show" (Paarl Post, 1911a:5; Paarl Post, 1917e:6). Other similar shows, for Whites, existed in Paarl and Worcester (Paarl Post, 1916b:2; Paarl Post, 1917a:3; 1917c:5; 1917d:5). Although the emphasis was on chrysanthemum displays, competition items such as "flowers for funeral purposes", "floral arrangements for the dining table" and "floral arrangements for the bride's table" were also included (Paarl Post, 1917b:3).

When a wild flower show was held on 3 October 1917 in Cape Town City Hall, entries were received from Wellington (Cape Times, 1917:8). The WHS however used the chrysanthemum flower for its competitions and the Cape Town mayor stated that Wellington had "become known as the home of the chrysanthemum" (Paarl Post, 1917a:6). Chrysanthemums were cultivated in China more than 3000 years ago (Machin & Searle, 1968:19). From Britain, it spread to the Cape Colony. It is uncertain when the chrysanthemum plant reached the Cape but evidence suggest that it may have been there by the 1860s. This is based on a newspaper report of 1862 about a Cape of Good Hope Agricultural Society that displayed other Chinese plants, namely primroses, at it's displays (Cape Argus, 1862:3). A Japanese influence in chrysanthemum competitions was however evident at horticultural shows in the Cape (Cape Town Railway Amateur Horticultural Society, 1912:10; Sun, 1935e:5; 1935f:6). By 1935, chrysanthemum competitions had spread as far as Carnarvon in the Northern Cape (Sun, 1935g:7).

Chrysanthemums were not amongst the blooms sold by Cape flower sellers. In the late 19th century, the media reported that: "... heath and flowers, gathered from the mountain slopes, are sold by Coloured folk in the city from six pence to one shilling per bunch" (Cape Register, 1899:27). They also worked with calendulas, daffodils, dahlias, dodecceasm, lilies, statice, roses and violets (Van der Ross, 2008:47).

The Sun reports that the WHS was established in 1916, with Albert Maurice as secretary, although the official version of the society states that five men (from Front and Park Street) met in 1917 to form the Society (Sun, 1932:4; Wellington Horticultural Society, 1997:12). According to Reggie Maurice, the WHS promoted a theme of social upliftment for lower class Coloureds by projecting images of "respectability" amongst the middle class (R Maurice, 16 November 2013):

Wellington was a peculiar place. We had a street called Kantienstraat... by 10h00 am it was literally carpeted with drunkards. My parents faithfully went there and tried to do something about it ... my mother was involved with the I.O.T.T. ... my sister still is.

At the time, Front and Park Streets were the residential areas of the upper echelons of Wellington's Coloured community and many were included in the voters' roll (Cape of Good Hope, 1905:94). These officials were young Coloured men who held more radical ideas than their parents. Reggie Maurice stated boldly that his grandparents and great-grand parents were regarded by the younger generation as "sell-outs" (R Maurice, 16 November 2013). However, they could pursue a social upliftment theme only to a certain level because the Union Prime Minister, General Jan Smuts, vowed to make South Africa a "White man's country" (Benson, 1969:35). This also affected social clubs of Coloured people at community level, forcing them to strive after "Whiteness" and at least one member of the WHS (Coloured) was registered as "European" while his father was listed as Coloured (Province of Cape of Good Hope, 1929:48).

The first competition of the WHS (Coloured) was held on Thursday 26 April 1917, in the Dutch Reformed Mission School, the day after the WTG held their show. The founding of the WHS also paralleled an upsurge of Afrikaner nationalist activities in Wellington. The newspaper reported how a certain C Kriel from Blauwvlei, had shown a film about Voortrekker and Afrikaner history during the same week (Burger, 1917b:3). By 1935, the WHS held its competition on the first Saturday of May, a tradition that exists up to the present (Sun, 1935d:2).

Occasionally the media reported on the activities of the WHS, and the Cape Times reported that one of the cultivators, Jonas Makatie, was "a wizard grower" (Wellington Horticultural Society, 1997:12). Makatie, who lived in Joubert Street, was also a part of Wellington's Coloured elite (Cape of Good Hope, 1905:110). Initially the WHS held Spring Shows in addition to the Autumn Shows, but these were discontinued (Wellington Horticultural Society, 1997:12).

Chrysanthemum competitions among Coloured people were not restricted to Wellington, and in 1919 a Sea Point Chrysanthemum Society (Coloured) held its first event on 24 April in the Sea Point Town Hall in aid of the Cape Corps Gifts and Comforts Committee (Clarion, 1919a:3). One of the organisers, Wepener, explained why a Coloured society was formed (Clarion,

1919a:3):

...for many years many of the [coloured] members had been competing in the local shows. Last year they were debarred from doing so and this year, when it was found they would not be allowed to compete. they tried to organise a show themselves in no spirit of opposition.

Sylvester Sam[p]son, the first champion bloom winner of the WHS, participated in the Sea Point Chrysanthemum Society's competition and won the 12-bloom division (Clarion, 1919a:3). The WHS possibly followed the same political path of "no spirit of opposition" to social racism preferring to subtly raising protest voices at championship displays. Reggie Maurice explained this situation as follows (R Maurice, 16 November 2013):

The WHS was started purely for social reasons, to keep the people occupied, that was what my father told me ... There was a dearth of opportunities for self-betterment .so the WHS gave them something to come home to after work . they did not speak politics there, except occasionally in the opening address ...they kept their association with Dan Retief out ofthe way and you had to sit and listen to the sins of this government... .

The WHS introduced a home industries section and in 1933 a poultry competition was added (Sun, 1933:5). There was often a prescence of mayors who invariably commended the participants. In 1933, the Mayor of Ceres, opened the competition proceedings with the words ". some of you are absolutely genii in flower artistry" (Sun, 1933:5). This dependence on White support was because Coloured clubs and societies could not act independently from sympathetic Whites. When the Gleemore Horticultural Society (GHS) hosted its chrysanthemum show in 1938, the chairman, remarked that if certain Whites had not come to the financial assistance of the Society, the show could not have been staged. The GHS therefore relied on the assistance of the Pinelands Horticultural Society (PHS), a White organisation, and invited its chairman, F Gardener, to open the show in Gleemore (Sun, 1938a:6).

Social features ofthe WHS

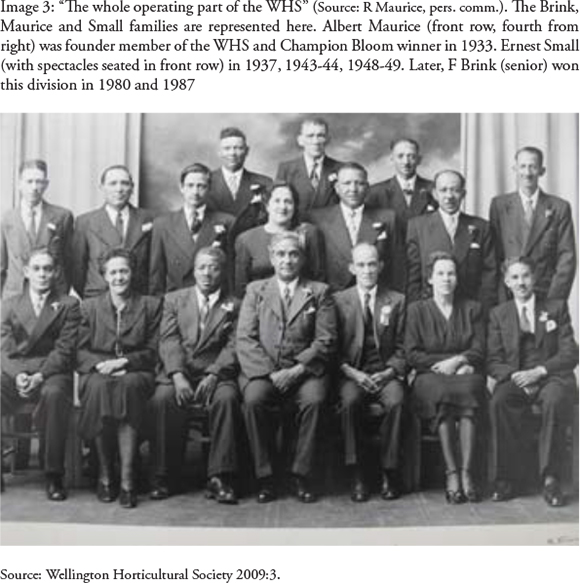

The WHS was controlled by "distinguished" members of society who were visible in multiple organisations. This is best illustrated by a newspaper report in 1933 that stated there was " ... a small but distinguished gathering of Coloureds and Europeans" (Sun, 1933:5). In clubs and societies, families often formed the core of the activities. Reggie Maurice therefore says: "... the Small family was always quite prominent in the society.... and the Brink sisters too..." (R Maurice, 16 November 2013). See Image 3 below:

The WHS offered people a social outlet and the Sun reported on a competition in 1932 in typical media style reporting of the pre-World War Two era where women's dress and decorative colour schemes were accentuated (Sun, 1932:4):

The WHS celebrated its 16th anniversary in the form of a social in the Unity Hall on 2 September. The hall was tastefully decorated with foliage and flowers. The many ladies present, all dressed in different colours, completed a colourful picture that was pleasing to the eye ... A little dancing brought a pleasant evening to a close. The music was provided by the Wellington String Band.

Salient features of "high culture" included sobriety and public decency. One of the earliest events organised by the Wellington branch of the APO on 1 June 1909, was a public debate on the subject: "Is drinking beneficial to the community?" (APO, 1909a:2). This substantiates the purpose of Sylvester Samson's, WHS champion in 1917, presidency of the Wellington Independent Friendly Society (WIFS), an organisation that promoted abstinence from alcohol (Smit, 2002). In 1909, the premises of the WIFS also served as the venue for the APO public meetings (APO, 1909c:3).

Coloured organisations did not have equal access to municipal facilities in Wellington and were subjected to the prejudices of the White community when applying for the use of these amenities. They often found that their traditional support in Town Councils were ineffective. In June 1917 the Meltons Cricket Club (Coloured) was refused permission to use the Town Hall for its dance. The reason for this refusal was: "White residents of the community have resolved that it was best not to go in for any public dancing, in view of the many casualties taking place. Under these circumstances the Council decided not to let the hall for such purposes" (Western Cape Archives and Records Services, 1917:183). The Coloured community therefore had, at times, to rely on leaders from their own ranks, with a reputation that matched the Daniel Retief's of the day, to take the lead in social matters. It is believed that it was the association between Albert Maurice and Retief that led to the formation of the WHS. Maurice, the first secretary, was described by Retief as a man who quietly and unostentatiously has gone on through the years, trying to make the shows an ever greater success (Sun, 1938b:4).

Albert Maurice and the WHS

One of the WHS founder members was Albert Vincent Maurice, principal at the Wellington African Methodist Episcopal (AME) school for more than 25 years, a founder member of a Teachers' League of South Africa (TLSA) Wellington branch, which was established there in 1923 and was on the voters' roll (Clarion, 1919e:8; Sun, 1932:4; 1936:5; Adhikari, 1993:51; Educational Journal, 1925: 6; 1926:15; Province of Cape of Good Hope, 1929:40. Maurice won the Champion Bloom in 1933, while his wife won the JJ Isaacs trophy in the home industry division (Sun, 1933:5). He was the grandson of Moorghem and Allutchemo Maurice, a Mauritian born immigrant (Western Cape Archives and Records Services, MOOC 6/9/836/2603). Morgan Maurice, a property owner, lived and died in Rosebank, Cape Town (Western Cape Archives and Records Services, MOOC 6/9/3825/28635). The Maurice family from Rosebank was part of the few literate elite in early 20th century Cape Town and Dorothea Maurice and James Maurice (Albert's siblings) won literary competitions organised by the APO in 1912 and 1913 respectively (APO, 1912c:2). Their brother, Sydney, was president of the Teachers' League of South Africa in 1921 and principal of the Trafalgar Public School (Paarl Post, 1921a:6).

From 1 March 1894, an agricultural show was held under the auspices of the Western Province Agricultural Society on land (in close proximity of Rosebank) donated by Cecil Rhodes (Serfontein, 1998:95-96). This might have shaped Albert Maurice's ideas on the potential value of horticultural shows. Albert Maurice arrived in Wellington in 1911 and Reggie Maurice remembered his parents as follows (R Maurice, 16 November 2013):

My father wasn't a great sportsman but he belonged to every flippin organisation that was in Wellington. My mother was involved in all kinds of things ... at least five days a week... She was an Abrahamse, sister of John Abrahamse, principal of the English Church School ...always doing social work, she ran the Nursing Society ... all kinds of little Societies ... women's rights ... and those kind of things ... in those days quite advanced positions to take.

Albert Maurice was involved in a host of organisations. He was player, official and Union delegate for the Roslins Rugby Football Club, captain of the Meltons Cricket Club, a founding member of the Allies Lawn Tennis Club and a few other community initiatives, that included serving on the local Wellington branch of the Governor-General's Fund (Clarion, 1919f:3; Sun, 1936:5). The game of tennis was especially used by the early Coloured leadership to display a badge of respectability as part of their upliftment theme. Reggie Maurice explained (R Maurice, 16 November 2013):

My father and his colleagues . like Sampson . spent a lot of time with tennis. They thought they could crack open the social structures ... because people saw themselves as inferior . there was a whole lot of blacks in his tennis team . you wont see that situation today ... 20 blacks in a lawn tennis team ... You see it was a one-on-one game so you could excel ... so tennis was his game of choice and he spent a lot of time on that. .

Albert Maurice was also part of a committee responsible for arranging the Wellington United Choir annual reception in the English Church Schoolroom (APO, 1913c:4). His brother, Sydney, was one of a few coloured graduates with a BA degree who was appointed principal of the Paarl Congregational Mission School in 1913 (APO, 1913b:4). Albert's brother-in law was John Abrahamse, principal of the English Mission School (R Maurice, 16 November 2013).

Communities in the Cape Province were affected by the establishment of the Coloured Advisory Council (CAC) in February 1943, which later evolved as the Coloured Affairs Department (CAD). A movement, the anti-Coloured Affairs Department (anti-CAD), emerged that opposed the CAD. Albert Maurice sympathised with the Anti-CAD Movement and Non-European Unity Movement (NEUM) (R Maurice, 16 November 2013). Because he was part of Wellington's very small middle class, he interacted socially with the Small family (R Maurice, 16 November 2013).

Contributions of the Small family

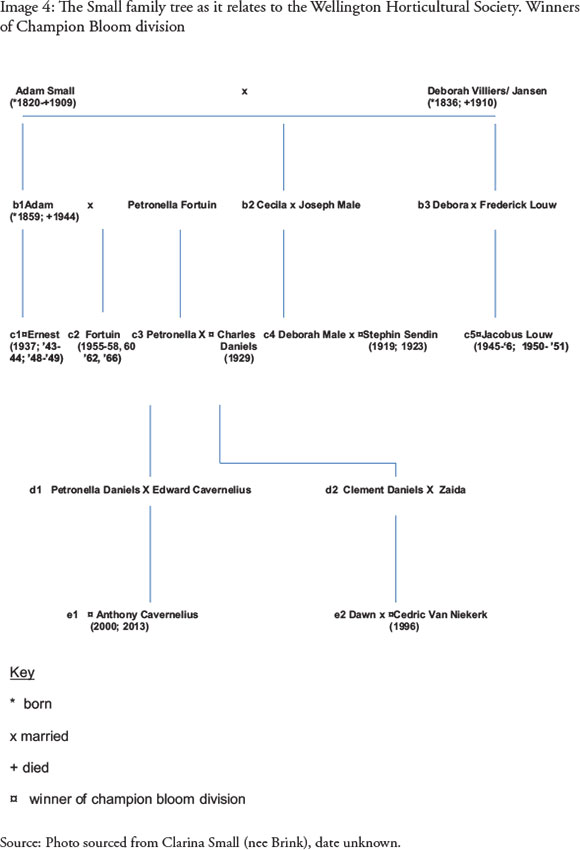

As mentioned previously, the Small family was prominent in community affairs in Wellington and between 1912 and 1914, a certain A. Small served on the Executive (APO, 1912a:3; 1913e:12; 1914c:11). In 1928 Lysa Small was secretary of the TLSA branch in 1928 (Educational Journal, 1928:13). There was also a historical intimacy between the WHS, competition and the Small family. This family can trace their history in the Wellington Uniting Reformed Church back to 29 December 1856 when the 35 year-old (Adam) Piet Small (1820-1909) married the 20 year-old Debora Maria Petronella Janse alias (de) Villers (1836-1910) in Wellington (Wellington Uniting Reformed Church, 1856). A possibility exists that they may be connected to Adam ('bastard') and Sella Smal(l) that stayed on the farm of Petrus Hauptfleisch in the Stellenbosch district in 1825 (Western Cape Archives and Records Services, 1825). An overview of the list of WHS champions, reveals a family heritage starting with the children of Adam Small (1820-1909) and ending with his great-great grandchild, Anthony Cavernelius. (See Image 4 below). The Small family also participated in other divisions of the WHS besides the chrysanthemum competition. In 1938, for example Ernest Small, who owned property at 13 Terrace Street, was the winner of the poultry (Sun, 1938c:4).

This family, was part of the early 20th century educated elite and organised themselves socially around dominant social cultural values. Some of them were addressed as "oom" and "ounooi" by their relatives. In 1919 the winner of the competition was Stephen Jakobus (oom Faan) Sendin. His social position was reflective of some Small family members of the time. He was married to a granddaughter (Deborah Male) of "ou-nooi" (De) Villers (1836 - 1910) and was a wagon maker on the 1927 voters' roll (Union of South Africa, 1927:41; Wellington Horticultural Society, 1997:3). Some Small family members formed marriage alliances with other WHS members, one such case being that between Fransina Small and Charles Daniels who was on the Wellington voters' roll (Union of South Africa, 1927:38). The Brink and Small families also formed a marriage alliance (See Image 5 below). A few of the family became teachers and in 1914 the APO mentioned that Roslyn (Slain) Petronella Small, sister of Ernest and Fortuin, obtained a teacher's certificate from the local mission school (APO, 1914a:4).

The Small family purchased fixed property on 6 August 1897 at 13 Terrace Street, Wellington (Cape Town Deeds Office, 1897 - T.6532; Western Cape Archives and Records Services, DOC 4/1/543). Both Adam Small (born 1820) and his wife died in this house in 1909 and 1910 respectively (Western Cape Archives and Records Services, MOOC 6/9/628/2465; 6/9/648/2003). In 1910, the property was sub-divided between two of their children, Adam Small (born 7 September 1859) and Cecila Male, neé Small (mother-in-law of Stephen "oom Faan" Sendin) (Western Cape Government, 1910:T.9297, T9298). They too died at 13 Terrace Street, Wellington.

It is possible that the family rented property nearby Terrace Street in 1878 since there was an Adam Small of present-day nearby Pentz Street on the voters' roll that year (Cape of Good Hope, 1878). Adam Small (born on 7 September 1859), father of Ernest and Fortuin, resided in the house in 1905 and was on the voters' roll (Cape of Good Hope, 1905:122). The house at Terrace Street displayed symbols of garden culture and was even named 'Ferndale' because of the ferns displayed on the stoep (M Cleophas, pers. comm.). Jacobus Louw, the 1945 and 1946 and again 1950 and 1951 winner of the champion bloom division was a cousin of Ernest and Fortuin Small, and also resided nearby in Terrace Street.

The family house in Terrace Street A was declared, "located in a White Group Area" in 1960, and Ernest Small unwillingly sold the property to the Wellington Municipality (Western Cape Archives and Records Services, DOC 4/1/543). Ernest Small's daughter remarked that the "improvements" (the new owners claim) to the house were really just changes -they sacrificed the intrinsic charm of the house and garden (Cleophas, 2012:28). Their lifestyle of an established 20th century middle class family with a cottage garden that reflected their social expectations, was destroyed by this forced removal under the Group Areas Act of 1950. By so doing the Small family's middle class, village homeowner, expectations were ruptured and may be described in the words of Bird and Llyod (1990:10):

Although the chief difference between a cottage garden and an allotment is permanence, the cottager was frequently under threat of expulsion of the landlord ... However if the village homeowner was conscientious he was able to continue in his original cottage for generations.

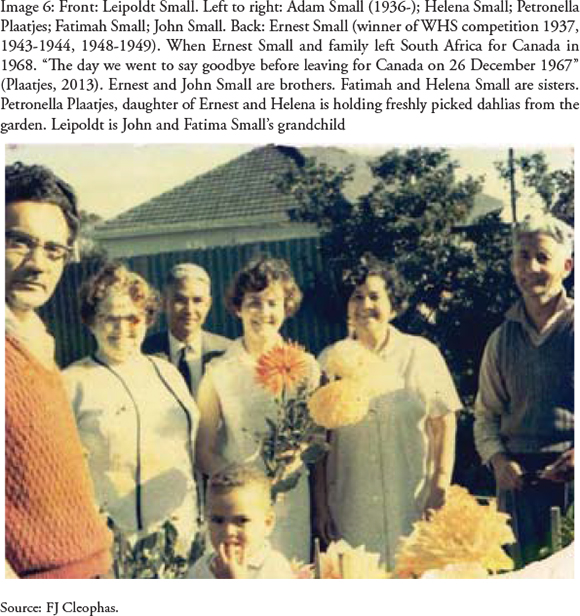

However, the cultivation of flowers remained a central feature of this family's activities in the 20th century and when Ernest Small emigrated to Canada in 1968, flowers formed an integral part of the farewell occasion. See Image 6 below:

Conclusion

This study is concluded by answering the research question: "How can narrative writing assist undergaduate students develop historical thinking?" Possibilities will be explored in terms of six concepts of historical thinking:

Historical significance

This aspect refers to historical data that results in change (the event had deep consequences, for many people, over a long period of time) and is revealing (the event sheds light on enduring or emerging issues in history and contemporary life or was important at some stage in history within the collective memory of groups). Significant topics might meet either of these criteria but not necessarily both (Peck & Seixas, 2008:1027).

The historical significance of the WHS is that it existed for nearly a century and it's members were visible in other organisations in the Cape Province. They were drawn from families who made inroads in post-colonial society but were stunted because of racist laws and policies. The descendants of the early WHS members thus have a legacy theme around which to construct a family history. It was also shown how the WHS used political strategies of compromise to advance their cause of social upliftment.

Evidence

This study used a wide range of evidence that included archival material, academic literature, books, memory recollection, newspapers and visual material. The framers of the Canadian Benchmarks of Historical Thinking Project emphasized the importance of being selective when using evidence (Seixas, nd). Therefore this research used evidence that was close to the topic under investigation.

Continuity and change

This aspect of historical thinking seeks answers for the question: "What has changed and what has remained over time"? (Seixas, nd). It was shown how flower growing remained a central feature in the family life of the Small family.

Cause and consequence

The concept of cause and consequence helps historians understand how and why certain conditions and actions led to others (Seixas, nd). The narrative of the WHS showed how the town experienced economic, social and intellectual prosperity during the early 20th century. Community leaders incorporated elements of family and competition into a garden culture, which became an integral part of middle class values, and in turn formed part of a "high culture". This went hand-in-hand with property ownership in suburbs and villages. Floral feasts, such as in Paarl (1911) allowed villagers, to display forms of village nationalism by raising objections to flowers outside villages being displayed at their local show (Paarl Post, 1911b:6) These developments laid the foundation that led to the establishment of the WHS. With time, the WHS developed into an organisation emphasising linkages between competition, class, community and family.

In this milieu, Coloured people organised clubs and societies around ideas of respectability that emphasised class and race identity. They were however marginalised from existing White clubs and societies and thus advocated social upliftment to prove their worthiness of attaining full political and social rights. At the same time, they expressed their racial identity by priding themselves in their closeness to Western culture. Ethnicity also implied practicing sensible recreation along the lines of respectability and being civilised. One sensible recreation activity for middle class Wellingtonians was flower growing in well-maintained gardens and entering them in competitions.

Historical perspectives

The CBHP explains the developing ofhistorical perspectives as understanding the "past as a foreign country" with different social, cultural, intellectual and emotional contexts that shaped people's lives and actions (Seixas, nd). This research showed how 20th century clubs and social institutions were centered around families. It was also shown how organisers of clubs and societies were visible in multiple organisations. The WHS was started during a period where family values and garden culture where seen as symbols of progress. These no longer hold the same sway during the 21st century. The 21st century is characterised by cyber technology, where very little (such as the chrysanthamum) remains foreign, the practice of competitions is largely organised by franchises and not clubs, garden culture is a rarity and the notions of family life are changing.

Moral dimension

This concept deals with how historians interpret and write about the past. It also relates to how different interpretations of the past reflect different moral stances today (Seixas, nd). Therefore, a contextualizing of a historical narrative of the WHS was necessary. The WHS was established during a time when racism against Coloured people intensified. Those leaders who emerged were religous men who voiced opposition against racism by actions what the saw as civilised and respectful. Such actions included the establishment of clubs and societies, such as the WHS.

References

Adhikari, M 1993. "Let us live for our children": The Teachers League of South Africa, 19131940. Cape Town: Buchu Books. [ Links ]

Adhikari, M 2002. Hope, fear, shame, frustration: continuity and change in the expression of Coloured identity in white supremacist South Africa, 1910-1994. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Adhikari, M 2006. Not White enough, not Black enough. Racial identity in the South African Coloured community. Cape Town: Double Storey. [ Links ]

Allerton, F 1949. Chrysanthemums for amateur and market grower. London: Faber and Faber. [ Links ]

APO (African Political Organisation), 5 June 1909a.

APO (African Political Organisation), 5 July 1909b.

APO (African Political Organisation), 31 July 1909c.

APO (African Political Organisation), 28 August 1909d.

APO (African Political Organisation), 24 August 1912a.

APO (African Political Organisation), 24 August 1912b.

APO (African Political Organisation), 21 December 1912c.

APO (African Political Organisation), 22 February 1913a.

APO (African Political Organisation), 8 March 1913b.

APO (African Political Organisation), 8 March 1913c.

APO (African Political Organisation), 3 May 1913d.

APO (African Political Organisation), 23 August 1913e.

APO (African Political Organisation), 20 December 1913f.

APO (African Political Organisation), 21 February 1914a.

APO (African Political Organisation), 30 May 1914b.

APO (African Political Organisation), 19 September 1914c.

APO (African Political Organisation), 29 May 1915a.

APO (African Political Organisation), 16 October 1915b.

APO (African People's Organisation), 24 July 1920a.

APO (African People's Organisation), 21 August 1920b.

APO (African People's Organisation), 14 May 1921.

Badham, A 1985. St. Mary's Anglican church as a window on turn-of-the-century Woodstock. Unpublished honours thesis. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Benson, M 1969. South Africa: The struggle for a birthright. Brentwood, Essex: Minerva. [ Links ]

Bickford-Smith, V, Van Heyningen, E & Worden, N 1999. Cape Town in the twentieth century. Cape Town: David Phillip. [ Links ]

Bird, R & Lloyd, C 1990. The cottage garden. London: Dorling Kindersley. [ Links ]

Booth, D 2005. The field. Truth and fiction in sport history. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Brutus, T 2013. Personal telephonic conversation with the son of Dennis Brutus, 9 September. [ Links ]

Burger, De 26 April 1917a.

Burger, De 28 April 1917b.

Burger, De 15 April 1925.

Cape Argus, 2 September 1862.

Cape of Good Hope 1878. List of persons residing in the electoral division of Paarl, whose names have been registered in July 1878 as qualified to vote in the election of members for the parliament of this colony. Cape Town: Saul Solomon. [ Links ]

Cape of Good Hope 1905. Voters' lists residing in the fiscal division of Paarl. Field-cornetcy, 5. Wellington. Cape Town: Government. [ Links ]

Cape of Good Hope Agricultural Society 1853. Annual Report, 1852. Cape Town: Saul Solomon. [ Links ]

Cape of Good Hope Agricultural Society 1862. Annual report for 1861 and 1862. Cape Town: Saul Solomon. [ Links ]

Cape Register, The 1898. Selling flowers in the Karoo, Christmas number. [ Links ]

Cape Register, The 1899. A flower seller, Christmas number. [ Links ]

Cape Times , The 1 October 1917.

Cape Town Deeds Office 1897. T.6532, 4 August.

CapeTown Railway Amateur Horticultural Society 1912. Schedule ofAnnual Chrysanthemum Show. Saturday April 20th 1912. [ Links ]

Clarion, The 26 April 1919a.

Clarion, The 8 May 1919b.

Clarion, The 10 May 1919c.

Clarion, The 17 May 1919d.

Clarion, The 28 June 1919e.

Clarion, The 24 December 1919f.

Clarion, The 13 December 1919g.

Clarion, The 24 July 1920.

Cleophas, FJ Private collection of photographs.

Cleophas, FJ 2012. Adam Small: familie geskiedenisse, aanlope en vroeër invloede. Tydskrif vir Letterkunde, 49(1):19-39. [ Links ]

Cleophas, FJ & Van der Merwe, FJG 2011. Contradictions and responses in the South African sport colour bar with special reference to the Western Cape. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance (AJPHERD), 17(1):124-140. [ Links ]

Donaldson, K 1916. South African Who's Who. Social and business. An illustrated biographical sketchbook of South Africans and South African businesses. Cape Town: K. Donaldson. [ Links ]

Educational Journal, The 1925. Branch branching. January-March 7(77):6.

Educational Journal, The 1926. Branch Reports. January-March 7(80):14-15.

Educational Journal, The 1928. Branch reports. August 7(88):10-14.

Firth, B (2013). "Powerful knowledge" in any history textbook? An analysis of two South African textbooks in the pursuit of powerful knoweldge. Unpublished M Ed thesis. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Garden Cities, 1972. Fifty years of housing. 1922-1972. The story of Gardern Cities. Pinelands, Cape Town: Gardern Cities. [ Links ]

Gerwel, GJ 1983. Literatuur en Apartheid. Kasselsvlei: Kampen. [ Links ]

Hall, C 1990. The sweet delights of home. In: M Perrot (ed). A history of private life. From the fires ofthe revolution to the Great War (47-96). Cambridge, MA: Harvard. [ Links ]

Hammerland, KG 2012. Promoting procedurla knowledge in history education. In: Ludvigsson, D. (ed.). Enhancing Student Learning in History: Perspectives on university history teaching (pp.117-130). Uppsala: Uppsala University. [ Links ]

Lewis, G 1987. Between the wire and the wall. A history of South African "Coloured" politics. New York: St. Martin's. [ Links ]

Machin, BJ & Searle, SA 1968. Chrysanthemums the year round. London: Blanford. [ Links ]

Maclean, M 2013. A gap but not an absence. Clubs and sports historiography. The International Journal ofthe History of Sport. 30(14): 1687-1698. [ Links ]

Martin-Fugier, A & Perrot, M 1990.The actors. In: M Perrot (ed). A history of private life. From the fires of the revolution to the Great War (95-260). Cambridge, MA: Harvard. [ Links ]

Maurice, R Private collection. [ Links ]

Molyneux, E 1890. Chrysanthemums and their culture. London: Edwin Molyneux. [ Links ]

Odendaal, A 2003. The story of an African game. Black cricketers and the unmasking of one of cricket's greatest myths, South Africa, 1850-2003. Cape Town: David Philip. [ Links ]

Paarl Post, 4 November 1911a.

Paarl Post, 11 November 1911b.

Paarl Post, 18 November 1911c.

Paarl Post, 22 April 1916a.

Paarl Post, 29 April 1916b.

Paarl Post, 28 April 1917a.

Paarl Post, 5 May 1917b.

Paarl Post, 13 May 1917c.

Paarl Post, 13 May 1917d.

Paarl Post, 6 October 1917e.

Paarl Post, 25 June 1921a.

Paarl Post, 16 July 1921b.

Peck, C & Seixas, P 2008. Benchmarks of historical thinking: First steps. Canadian Journal of Education, 31(4): 1015-1038. [ Links ]

Personal interview, M Cleophas (granddaughter of Adam Small, 1859-1944)/F Cleophas (Researcher), 21 August 2013. [ Links ]

Personal interview, R Maurice (son of Albert Maurice)/F Cleophas (Researcher), 16 November 2013. [ Links ]

Province of the Cape of Good Hope 1929. Voters' list. Electoral division of Paarl. Government: Pretoria. [ Links ]

Retief, PJ 1988. Die Retief familie in Suid-Afrika. Pretoria: PJ Retief. [ Links ]

Rigby, LM & Russel, CEB 1908. Working Lads Clubs. London: Macmillan. [ Links ]

S.A. Spectator, 1902. A trip to Wellington, 6 December. [ Links ]

Serfontein, J 1998. Kaapseskou van Paddock na Rosebank en Goodwood. Goodwood: Nasionaal. [ Links ]

Sexias, P nd. Teacher notes: Benchmarks of historical thinking. A framework for assessment in Canada. Available at: http://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/cur/socstud/foundation_gr8/tns/tn1.pdf. Accessed on 22 May 2014. [ Links ]

Smit, E 2002. Die geskiedenis van Wellington en distrik tot die jaar 2000. Wellington: CD-Rom. [ Links ]

Sun, The 16 September 1932.

Sun, The 12 May 1933.

Sun, The 5 April 1935a.

Sun, The 19 April 1935b.

Sun, The 3 May 1935c.

Sun, The 3 May 1935d.

Sun, The 3 May 1935e.

Sun, The 3 May 1935f.

Sun, The 24 May 1935g.

Sun, The 28 August 1936.

Sun, The 7 May 1937.

Sun, The 13 May 1938a.

Sun, The 13 May 1938b.

Sun, The 13 May 1938c.

Thompson, LM 1949. The Cape Coloured franchise. Johannesburg: South African Institute of Race Relations. [ Links ]

Union of South Africa 1927. Province of the Cape of Good Hope. Voters' list, 1927. Electoral division of Paarl. Cape Town: Cape Times. [ Links ]

Van Eeden, E 2013. Informing history students/learners regarding an understanding and experiencing of South Africa's colonial past from a regional/local context. Yesterday & Today, 10:25-47. [ Links ]

Van der Ross, RE 1975. The founding of the African People's Organisation in Cape Town in 1903 and the role of Dr Abdurahman. Pasadena, CA: California Institute of Technology. [ Links ]

Van der Ross, RE 1986. The rise and decline of Apartheid. A study of political movements among the Coloured people of South Africa, 1880-1985. Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Van der Ross, RE 2007. Buy my flowers! The story of Strawberry Lane, Constantia. Cape Town: Ampersand. [ Links ]

Van der Ross, RE 2008. The Black countess. A biography. Cape Town: Ampersand. [ Links ]

Wellington Horticultural Society 1997. Annual Flower Show Brochure. May. [ Links ]

Wellington Uniting Reformed Church 1856. Marriage register, No. 1705 29 December. [ Links ]

Western Cape Archives and Records Services 1825. Muster roll for Stellenbosch. J. 279, 25 May. [ Links ]

Western Cape Archives and Records Services 1917. 3 Wel 1/1/1/5a, Minutes of meeting of the Wellington Town Council held on 5 June. [ Links ]

Western Cape Archives and Records Services, DOC 4/1/543, no.3452.

Western Cape Archives and Records Services, MOOC 6/9/10930/92313.

Western Cape Archives and Records Services, MOOC 6/9/3825/28635.

Western Cape Archives and Records Services, MOOC 6/9/628/2465.

Western Cape Archives and Records Services, MOOC 6/9/648/2003.

Western Cape Archives and Records Services, MOOC 6/9/836/2603.

Western Cape Government 1910. Deeds Office, T.9297 and T.9298 of 22 December.

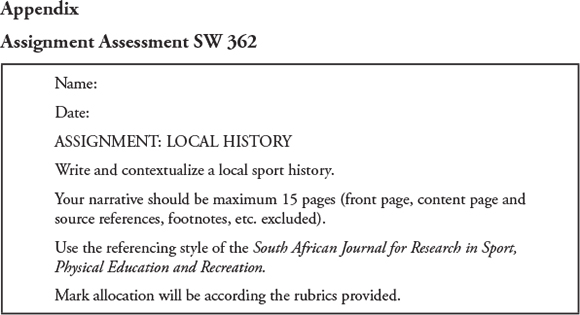

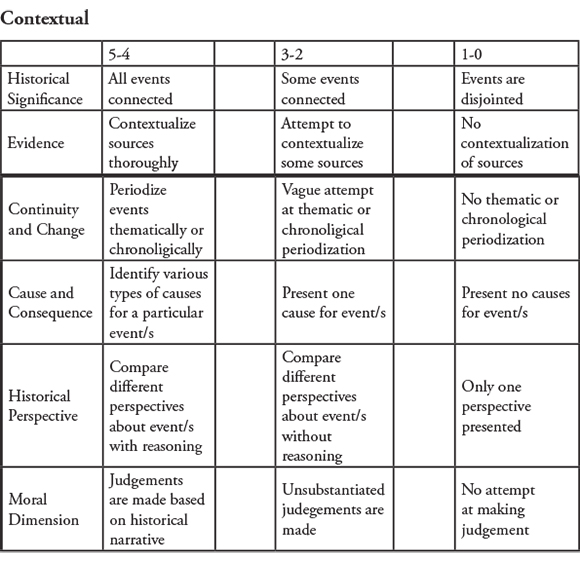

Appendix