Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.8 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2012

ARTICLES

Running a history programme outside the classroom. a case study of athletics at Zonnebloem College

Francois J Cleophas

Senior Lecturer Stellenbosch University fcleophas@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Sport history has been neglected, even ignored, in South African classroom and pedagogy debates. Despite, a large reservoir of South African sport history literature of a formal and informal nature being available for teachers, other historical areas of concern are usually focussed on. This study attempts to break this mould and offer history teachers an opportunity for creating pedagogical opportunities outside the formal history curriculum. In order to achieve this, a history of athletics at the Zonnebloem College during the 19th and early 20th centuries was researched. A brief literature overview of previous research on Zonnebloem history is presented as background material. The study is then introduced with a historical oversight of school athletics in 19th century England. Next, the historical development of sport during the 19th century at Zonnebloem is explored. The crux of the historical account hones in on the history of athletics at Zonnebloem during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Finally, the article is concluded by presenting teachers with pedagogical opportunities outside the classroom through the interrogation of historical sources, all of which are taken from the Zonnebloem historical narrative.

Keywords: Athletics; Colonial education; Muscular Christianity; Pedagogical opportunities; Zonnebloem College; Sport history.

Background

In order to proceed with the act of history study, it is important to know what interpretations have been presented in the past by the major scholars in the field.1 A cursory literature overview shows there are patches of formal history research that hones in on Zonnebloem College. In 1975 Janet Hodgson received a Masters degree from the University of Cape Town, for a thesis, "A history of Zonnebloem College, 1858 to 1870. A study of church and society". This two volume, 667 paged work, makes reference to cricket and one athletic meeting for Zonnebloem Old Boys held at St. Marks Institute in the Eastern Cape.2 Twelve years later, Hodgson's article, Kid gloves and cricket on the Kei appeared in Religion in Southern Africa. This article details the historical development of events surrounding an Old Zonnebloem Boy's reunion at St Mark's institute in the Eastern Cape in 1869 where athletic events were organised as part of the celebrations.3 Hodgson's work on Zonnebloem cricket was repeated in Andre Odendaal's ground-breaking book, The story of an African game, released in 2003, that detailed the history and experiences of black African cricketers.4 In 2009, Francois Cleophas received a PhD from Stellenbosch University for a dissertation, Physical education and physical culture in the Coloured community of the Western Cape, 1837-1966 where he included the historical development of physical education at Zonnebloem in his work.5 Because the focus of these works was not athletics, the authors either ignored or treated the subject as supplementary evidence for a broader research topic.

Although athletics at Zonnebloem and all other mission institutions never reached the attention of mainstream (White) sport, these athletes were "talked about in a manner where their names lingered in a school a few years after they have left, like your all-rounder, your sprinter and miler and high jumper...".6 In order to gain historical insight into the practice of athletic participation at Zonnebloem College, it is useful to "identify the overarching issues which . need to be considered in interpreting historical change, such as the political, social and economic forces and processes, or the context that needs to be understood".7 Since the nature of the above mentioned research works do not allow for an in depth historical analysis of sport at Zonnebloem, there is a need to place such a focus at the core of inquiry.

Introduction

Toward the end of the eighteenth century a missionary revival in Europe corresponded with merchants and manufacturers looking for new markets in Africa and the rest of the world. They often used moral or Christian arguments to justify taking over Africa and other parts of the world.8 By the middle to late 19th century, it was expected from the loyal, brave and active aristocratic young British man to portray a public image of sport participation as a good alternative to gambling and alcohol abuse or "riotous living".9 British education opinion makers such as Matthew Arnold reasoned that the sons of the working class would benefit more by gymnastics than games.10 Therefore, when a gymnastic club was started in the Eastern Cape in 1867, it prompted an editorial that stated: "... athletic sports undoubtedly beneficial for gymnastics... ".11

However, at the time, cricket was the great game throughout the motherland and colonies of the empire. Football was played when the weather was too bad for cricket and tended to be a loosely organised activity within schools.12 Athletic meetings were thus considered not as important as cricket and football.13 When a former Zonnebloem student remembered with great sadness the football and cricket he left behind, he said nothing about athletics.14

A common feature of elite 19th century English schools was self-imposed isolation from community sport. For example, in 1858 the principal of Winchester, Dr. George Moberly, refused the cricket team permission to play a match in the town because of "the dangers to their morals".15 Athletics however had a presence in English schools, based on this isolation principle, from at least 1837 when Rugby School instituted its "fearsome cross country, Crick run" and soon afterwards several other public schools introduced athletics into their sport curricular. The universities followed suit and in 1850 Exeter College Athletic Club was formed in Oxford.16 The South African Olympian, Bevil Rudd, who studied at Oxford University states: "Before the formation of the Achilles Club in 1920 all our energies and enthusiasm were concentrated on the Oxford and Cambridge Sports....17 Nobody was particularly encouraged to enter for the national championships, or other big meetings, and very few did. we rarely met or matched ourselves against the great and more experienced athletes from other clubs. athletes followed a training course "preceded by the taking of emetics and purgatives to dislodge the obnoxious crudities in the body... the whole scheme was Spartan-violent and disagreeable".18 Some of these students ended up serving the Empire in the outlaying colonies, including the Cape Colony's educational institutions like Zonnebloem College in Cape Town.

Zonnebloem College and sport

A major driving force behind the establishment of Zonnebloem College was Governor George Grey who, at a time of increased tension at the eastern frontier, is recorded as saying:19

Mission stations were less costly than armies. Education and industry would do more to ward off fresh rebellion than European troops...the frontier wars had already cost too much in valuable lives and money. At present Great Britain is at war with Russia, if another frontier war broke out, it might be difficult to find enough men to quell it.

The Zonnebloem College was established in February 1858 at Bishop Gray's home20 in Claremont, Cape Town but moved to the Zonnebloem estate near District Six on 4 January 1860.21 This site was chosen because it "was within reach of the highest civilisation in South Africa and yet separated from the contamination of the Town".22 Between 1858 and 1913 Zonnebloem had a non-racial student population, coming from Baleya, Barotse, Bechuana, Coloured, Fingo, Gcaleka, Marolong, Matabeli, Mosutho, Pondomiso and White communities.23 These boys were cricketers rather than athletes.24

At the turn of the 20th century, the Zonnebloem's staff was completely made up of Oxford or Cambridge graduates, with the exception of one. In 1901, the Teacher Training School staff consisted of: William H Parkhurst (Jesus College, Oxford); FP Macirone (St John's College, Oxford); G Ingham (Morton College, Oxford); A Hopkins (Jesus College, Cambridge), WL Castley and Henry Kilili Poswayo.25 Poswayo, a South African born teacher, left for England in June 1904 to continue his education at the St Augustine College in Canterbury, England, where sport was part of the curriculum.26

From early in its history, the Zonnebloem authorities tried to mould the students into a disciplined class of subjects who were loyal to the British Empire. These students were taught the objective of acquiring good conduct, being obedient, attentive and willing to learn.27 According to the historian, Janet Hodgson, introducing games was used as a means to achieve these objectives, for the boys at least.28 She refers to a report, written in 1859, a part of which read:29

So intent are they, the boys, on the pursuit of knowledge that they can scarcely be persuaded to employ their play hours otherwise than in learning lessons and in teaching one another; and probably it will be found as necessary for a time to provide them with systematic instructions in boys games as in any other department of learning.

Drilling was introduced into the curriculum; but it was the only discipline to which some of the older boys did not yield to quite so cheerfully. It was suggested that their reluctance was more likely due to their not understanding the object of the exercise, rather than from any dislike of it; and that being so tractable, they would soon become reconciled to this activity.

Many of the Zonnebloem students internalised values of Victorian decency and conduct as a counter measure to prevailing 19th century racism. Municipalities outside Cape Town did not hesitate to use social misconduct as an excuse to segregate sport provision, favouring Whites. In Stellenbosch report was made in 1880 about "improper scenes occurring on Adderley Square such as fighting and using obscene language between the Europeans and Coloured boys playing football and other games." Segregation was soon to follow where students from the Victoria College Cricket Club and pupils of Stellenbosch Gymnasium were allowed to play on the "Square while Coloured schoolboys had to play their sport on the "Flats".30 Fifteen years prior to these developments, the Zonnebloem boys were taken on a visit to Stellenbosch where colonial race consciousness reared its head in the broader community and in sport. According to the boys' accounts, their cricketing equipment was considered to be an essential part of their baggage when they embarked on their journey by train and a highlight of their holiday was engaging the local Stellenbosch village boys in a game. The only Africans that most members of the farming community would have encountered in the normal course of their day would have been slaves. It is clear from a composition written by one of the boys, Walter Monde, that the arrival of a large party of well-dressed black schoolboys caused a sensation in the "dorp". He wrote:31

We arrived in Stellenbosch about one O'clock; and... ...after we had our dinner,we went outside, and Stellenbosch people were very anxious to see us; great many of them went out from their houses to look at us; and it seemed to us that they never saw people (meaning Africans) bfore,... we came back and saw ... young men that were playing ...cricket our favoured game and they kindly asked us if some of us would play, and we were very much obliged to them and some of us played with them, and when play was finished their Captain came and asked if we would like to have a match with them, we said yes we would try.

The first pupils from the Eastern Cape were hostages for peace, many having family relations with Robben Island political prisoners. The pupils led a sheltered life and had little association with the outside world.32 Regular sport games at Zonnebloem, with outside bodies, therefore never became a common feature. Rather, the boys' physical needs were catered for, besides cricket, by regular walks in the mountains of Cape Town.

Zonnebloem students and athletics during the 19th century

Walking

Although mid-19th century Capetonians had access to a horse drawn tram service they had no sophisticated public transport system.33 The Zonnebloem boys and those charged with their care were mostly dependent on a pedestrian mode of transport. However, exercise walking was known to Capetonians in the 1850's and an Englishman, W.H. Thompson, presumably walked from the telegraph office to Simons Town in three hours and 35 minutes for a monetary reward of 100 pounds.34

Table Mountain and its surrounding area provided 19th century Zonnebloem students, staff and those associated with the College opportunities for recreational walking.35 On 20th April 1858, Rev. Lightfoot visited the 'Zonnebloem' boys36 at Bishopscourt and "had a beautiful walk... among the evergreen groves" and on 15th May he "went up Table Mountain with Mr. Ogilvie37 ... we started about 8 o' clock and returned about half past four...".38

The boys were free to explore the surrounding mountainside on Sunday afternoons, accompanied by their teachers. A favourite outing was the climb to the Blockhouse. Perched as it was, in a strategic position on a prominent knoll, it commanded a view of sea and city, mountain and plain. The water flow from the mountain became very erratic in summer, and so a cement catchment was constructed, the water being stored for domestic use. Later on, a small swimming pool was built alongside, for the boys.39

In 1859, George Mandyoli Maqoma and Boy Duke of Wellington Tshatshu, two Zonnebloem students, were sent to study under the tutelage of a parish priest at Nuneaton in Warickshire. Two years later, four more pupils, Edward Dumisweni Maqoma, Jeremiah Libopuoa Mosoeshoe, Samuel Lefulere Moroka and Arthur Waka Toyise were selected to attend St Augustine's College at Cantebury. In 1866, three more Zonnebloem pupils were sent, one being Nathaniel Mhala.40 Sport was part of the curriculum at St Augustine's and when Lightfoot attended there in 1855, his experience of "being able to speak learnedly on ... sport.. .stood him in good stead".41 Lightfoot's favourite pastime at St. Augustine's was walking and with "three or four exceptions not a day passed without him going for a walk".42 It was during this time period that formal athletics in England was taking shape.

Competitive athletics

The year, 1862, is presented by historians as a benchmark for the advent of modern athletics in the British Empire. That year, the West London Rowing Club presented its first athletics meeting with the Liverpool Athletics Club organizing an Olympic Festival in the same year. Of historical interest is that in addition to the ordinary running and walking events, high-jump, long jump, pole-vault, cricket ball throwing, discus, boxing, wrestling, fencing and gymnastics featured on the programme.43 Some of these events featured in athletic meetings organised by Zonnebloem boys in the early 20th century.

Most of the early Zonnebloem graduates were placed in the district of St. Mark's Mission Station in Independent Kaffraria, Eastern Cape.44 St. Mark's Mission Station was started in 1855, near present day Queenstown on the White Kei River, by Rev. H.T. Waters.45 Gray's suggestion of an Old Zonnebloem Boys reunion to be held at St Mark's Mission was implemented from 3 to 5 November 1869 and sport activities were organised for each of the three days. These included events similar to the West London Rowing Club's programme: 100 and 200 yard foot races, throwing a 25 pound weight, long jump and throwing the cricket ball. Edmund Sandile threw the ball farthest, Arthur Toise won the long jump and Stephen Mnyakama won the 100 and 200 yards foot races as well as the 25 pound weight throw.46 This was a departure from the more common form of sport where the colonists would let a fat smeared pig loose for any interested 'Hottentot' to be taken home.47 On the other hand there was a prevailing Puritan atmosphere at the frontier that was represented by the Rev. Morgan who "interfered with the amusement of the people... officially visiting families and advised those who danced to abstain from partaking of the Sacrament". It is not certain, whose idea it was to include athletic events as part of the reunion celebrations since the Bishop Gray was not specific about the details: "I thought that in many ways it would do good for all the Zonnebloem boys that have left to meet, and hold partly a social and partly a religious Conference".48

The St Mark's meeting preceded the first attempt to involve the general public in athletics in Cape Town in 1873. A prominent figure in the organisation of this meeting was the Anglican Dean, Reverend Charles William Barnett-Clarke. The Dean would have known Zonnebloem well since the boys went to the St George's Cathedral, where he presided, for church services.49

Zonnebloem students and athletics during the years, 1900 - 1908

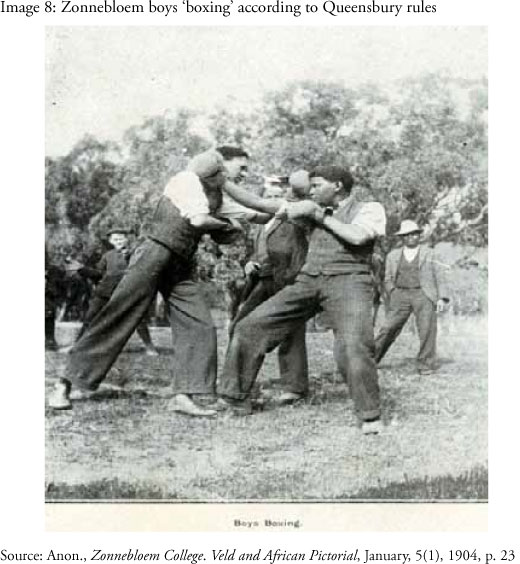

Although attendance at Zonnebloem College represented a measure of status, the facilities of the school division, at the turn of the 20th century, was not conducive to learning. When Oscar Hine joined the staff in 1904, "he taught some sixty boys single-handed in a small and miserable classroom".50 Shortly after his appointment, the College Magazine reported that "... in the matter of athletics, the College is a little less backward than formerly".51 Zonnebloem deliberately strove after high standards of performance in all aspects of school-life, including the extra-mural curriculum. This attitude lingered after the period under review. A political activist, Richard Dudley, remembers how Zonnebloem students 'thrashed' Livingstone High School in a school sponsored debate in the early 1930's.52 However, Zonnebloem, like most educational institutions during the early 20th century, was conscious of a civilisation theme that promoted decency and respectability. The sport of boxing at Zonnebloem was therefore allowed according to the Queensbury rather than the London (barefist) rules. At the same time some African boys still continued playing their indigenous games: Seloka (Bechuana); Insema (Matebele) and Karete (Basuto) (Zonnebloem College Magazine.53

At the turn of the 20th century, all learners had access to the ample sport facilities that the school advertised:54

A large portion of the College Grounds is devoted to the purpose of cricket, football and healthy recreation, in which all members of the Institution are required to take part. An enclosed swimming bath is also provided for the use of students.

The warden, William Parkhurst, elaborated on the habit of "stewing or loafing amongst the bigger fellows, i.e. pouring over a book or lolling in a classroom or at the foot of a tree in recreation hours, always with a schoolbook".55 This, he claimed, resulted in the tendency at Zonnebloem to give way to headaches, catarrh and physical laziness. There was a situation amongst students where they are "not found enjoying a rousing healthy game on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons but strolling with backs like capital D's... with the intricacies of English spelling, the names of rivers flowing into the Mediterranean, or the dates and causes of the many 'Kafir' wars".56 The ideal student was however one described in a poem, most likely by Rev. Musselwhite, presented on a Zonnebloem Speech day:57

An Ideal

O listen, brothers, to my rhyme;

I sing a song of olden time When ev'ry boy at school, they say, Was excellent at work and play. Ahl Nowadays, (the truth is sad!) This cant be said of every lad, For some are good and some are bad,

And some of them are in between; Yes, some  you know the sort I mean  Yes, some are in between. There was a jolly schoolboy once, At lessons he was not a dunce, In manly games he led the school, He never, never, broke a rule; Remembered all that he was taught, And always did just what he ought. In fact this boy would now be thought A very rare phenomenon. In fact a perfect paragon, A rare phenomenon.

Of prizes he possessed a score, And every term he added more,

He'd trophies of the playing field; His team would always win the shield; He'd find cube roots, run, jump or swim; It made no difference to him, For he was sound in head and limb; He'd brain, and he had muscles too. He'd brain  so (more or less) have you  He'd brain and muscle too.

When someone said "I pray you tell How 'tis you always do so well?"

He answered very modestly "Don't make me out a prodigy! For all can do what I have done, The secret is an open one, Just stick to what you've once begun And do your best  your level best." (Good sense, though slangily expressed) "Just do your level best."

By then an extra-mural sport programme was underway at Zonnebloem and the College Magazine called for healthy games that will "duly exercise the body and with it the brain, which will be better able to do its work".58 When Hine joined the staff as the manual work teacher, he was also charged with supervising the "out of doors matters generally".59 He brought with him an experience of British public schooling received at Manchester Grammar School and sport was gradually introduced on a formal basis.60 The clergyman was a carrier of Muscular Christianity values that centred around the idea of a "well-knit" body as model for a well-formed mind that harmonised as a basis for spiritual health with external principles of growth and order.61 It was believed that this could be achieved through an education system that produced manliness, courage, patriotism, moral character and team spirit. It was the acceptance of these notions that contributed to an increased interest in school sport and physical education in the last half of the 19th century.62 The public school came to be regarded not only as a conservatory for learning manliness, but also the home of games. Over time games and British manliness became synonymous.63 With his passing, on 16 May 1943, the College paid tribute to him in the following way:64

Thirty-nine years ago a young man, born in Jersey and educated at Manchester Grammar School joined the staff of Zonnebloem College, first as assistant master and for the last 12years as warden, devoted all his life and energies to the spiritual and educational work of that institution... a man of prayer, of quiet, unobtrusive, service, never pushing himself forward into the public eye, but to be quietly efficient and carefully accurate in all his work.

However, the College authorities continued expressing concern about the low motivation for sport participation among the boys and stated: "Football will be extinct because of a lack of interest in the game and a love of books... The students in general fail to understand the importance of exercises in maintaining good health".65

The first recorded 20th century athletic meeting of the Zonnebloem College was held on 3 September 1904 (see Table 1). A report of this meeting in the Quarterly Magazine shows to what extent British culture had infiltrated Black elite society. Here Mrs. Parkhurst, the warden's wife, presented the prizes and was herself presented with a bouquet. An athlete, Daniel Moshesh, presented it and the programme was:66

... followed by hearty and approving applauds. A musical programme was performed under the directorship of Michael Gaboutloeloe, who led the Bechuana choir in amusing the onlookers with choruses and comic items. The warden urged the boys to keep up their athletics and congratulated them on their great success that day. Afterwards, George van der Hoven and Joseph Moshesh were each presented with a gold-nibbed fountain pen for the trouble they had taken in arranging the sports. "God save the King" brought the evening to a close.

The manner of reporting athletic events at Zonnebloem, during the early years of the 20th century, reflects Victorian era descriptive sport writing that provides great detail about the weather and spectators and always presenting a positive picture of the day:67

... unfortunately the weather was unfavourable and (the meeting) had to be postponed. This delay was however a good omen in itself... It seemed as if the boys were not to have their sports, for rain and wind greeted the early birds on the two following Saturday mornings, which meant that the sports could not be held on either of those two days. Training was now in full swing, and on the following Saturday the sports were really held. A committee of five was elected by the whole school, who through the combined efforts made the sports a great success, so much so, that some numbers of boys were disappointed they had not entered for some events... the purchasing of prizes was left to Mr. Ames, who managed to produce out of professor Bosco's silk hat a large variety of very useful articles eg. fountain pens, clocks, ink bottles, a football, ink stands, belts, tennis shirts and a host of other articles too numerous to mention.

In 1905 a swimming race, diving competition, throwing the cricket ball and kicking the football were added to the existing athletic programme.68 On 23 December 1907 Zonnebloem athletes competed outside the school in a Cape Town Gala Sports Day at the Green Point Track (see Table 2). This meeting reflected a 19th century rural festival (rustic sports) atmosphere that included, besides the standard running and jumping events included three-legged and obstacle races. It is also the first mention of a Zonnebloem athlete, Paul Heneke, competing in a hurdles event.69 Some of these pupils, like Harold Cressy and Paul Heneke became school principals and took the values of Zonnebloem sport with them.70

Cressy and Heneke both became principals of the Trafalgar High School in Cape Town and served on the executive of the Teachers' League of South Africa (TLSA). The TLSA organised the first inter-school athletic meeting for Coloured children in 1916 at the Green Point Track in 1916, known as the Alexander Cup Sports Competition.75 When the Trafalgar High School Wieners Day Sports meeting was launched in 1933 at the Green Point Track, ten schools, four athletic clubs and the Old Trafalgar students entered teams in the competition.76

Employing Zonnebloem's athletic history as a pedagogical opportunity

One of the general aims of the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) History Further, Education and Training (FET) band for grades 10 -12 is "Acknowledging the rich history and heritage of this country as important contributors to nurturing the values contained in the constitution".77 Practical considerations negate the possibilities of Zonnebloem's athletic history complying with this aim within the confines of a classroom but it opens pedagogical opportunities for school history societies taking students on excursions. Such pedagogical opportunities should be underpinned by historical thinking concepts of: historical significance, using primary evidence, identifying continuity and change, analysing cause and consequence, taking historical perspectives into account and understanding moral dimensions of historical interpretations.78 The following questions, aimed at grade ten learners and based on images and extracts in the text above, are based on these concepts and serve as initiators for pedagogical opportunities.

Answer the following questions based on visual images of Zonnebloem's sport history:

Image 1

How does this image reflect Hodgson's statement that the site for Zonnebloem College was chosen because it "was within reach of the highest civilisation in South Africa and yet separated from the contamination of the Town"?

What aspects of the photograph suggest an English character?

The staff at Zonnebloem College in the 19th century promoted English culture through sport. What sport codes do you associate with 19th century England?

Image 2

What suggests that Zonnebloem offered its pupils a classical education?

Image 3

Describe the facilities available for drilling at Zonnebloem at the turn of the 20th century.

Image 4

What evidence exist that Zonnebloem had a swimming pool in the 19th century.

Images 5 and 6

Refer to Lightfoot's diary and use his entries to construct a timeline that shows the places he walked in Cape Town.

What indications are there that the Zonnebloem boys emulated Lightfoot?

Use the pencil sketch of Lightfoot and contrast it with a competitive road walker in the 21st century.

Image 7

What differences would there be between an athletic meeting held in 1869 at St Mark's Institution and Zonnebloem Nest in 2013?

Image 8

Do you think boxing was taken up seriously at Zonnebloem? Use the image to substantiate your answer?

Image 9

What aspects of the image represent the values of Muscular Christianity?

Image 10

If Harold Cressy would organise an athletic meeting, what educational institution, other than Zonnebloem, would he use as a model? What would this entail?

Answer the following questions based on extracts from Zonnebloem's history

Extract 1

" Gray's suggestion of an Old Zonnebloem Boys reunion to be held at St Mark's Mission was implemented from 3 to 5 November 1869".

In which way was the athletic meeting at this reunion different from a 21st century school athletic day?

Extract 2

... unfortunately the weather was unfavourable and (the meeting) had to be postponed. This delay was however a good omen in itself... It seemed as if the boys were not to have their sports, for rain and wind greeted the early birds on the two following Saturday mornings, which meant that the sports could not be held on either of those two days. Training was now in full swing, and on the following Saturday the sports were really held. A committee of five was elected by the whole school, who through the combined efforts made the sports a great success, so much so, that some numbers of boys were disappointed they had not entered for some events... the purchasing of prizes was left to Mr. Ames, who managed to produce out of professor Bosco's silk hat a large variety of very useful articles eg. fountain pens, clocks, ink bottles, a football, ink stands, belts, tennis shirts and a host of other articles too numerous to mention.

Anon., "The College Sports", Zonnebloem College. Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist 2(10), 1904, pp. 16-17.

How does the report show that this athletic meeting was successful?

Complete the following exercise:

The following is a blank entry form for an athletic meeting in 2013. Use the result sheet of the 1904 Zonnebloem meeting (Table 1) and identify suitable athletes, under the age of 18, to participate in the events on the form.

What events are different in the 1904 programme (Table 1) to the one in 1907 (Table 2)?

Conclusion

This paper has attempted to present history teachers with pedagogical opportunities outside the formal curriculum. It started identifying previous interpretations by recognised scholars in the field. Next, a knowledge base in the field of English sport history was presented that enables the teacher to proceed with a Zonnebloem case study. This was followed by identifying the historical development of recreational walking and competitive athletics at Zonnebloem. Finally the study was concluded with a pedagogical exercise for grade ten learners. All of this leads to possibilities for running a history programme outside the classroom. This could include agitating for a declaration of heritage sites (Zonnebloem College, St Mark's Institution and Table Mountain walking routes) and extra-mural classroom activities for a History Society (tours, archival visits and exhibition projects). There are also possibilities for student interaction between present day Cambridge, Oxford and Zonnebloem students.

~~1P Kallaway, "History in Senior Secondary School CAPS and beyond: A comment", Yesterday & Today, 7, July 2012, p. 30.

2 JKH Hodgson, "A history of Zonnebloem College", 1858-1870. A study in church and society", Vol. 1 & 2 (MA, UCT, 1975), pp. 164, 453-455, 538.

3 JKH Hodgson. "Kid gloves and cricket on the Kei", Religon in Southern Africa, 8(2), July 1987, p. 75.

4 A Odendaal, " The story of an African game. Black cricketers and the unmasking of one of cricket's greatest myths, South Africa, 1850-2003" (Cape Town, David Philip, 2003), pp. 24-27.

5 FJ Cleophas, Physical education and physical culture in the Coloured community of the Western Cape, 1837-1966 (Unpublished Phd dissertation, Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch University, 2009), pp. 83-92.

6 E Mphahlele, Down Second Avenue (London, Faber and Faber, 1959), p. 129. [ Links ]

7 P Kallaway, "History in Senior Secondary School..." Yesterday & Today, 7, July 2012, p. 30.

8 P Christie, The right to learn (Braamfontein, Ravan, 1985), p. 63.

9 H Spencer, Education. Intellectual, moral and physical (London, Williams & Norgate, 1911), p. 79.

10 PC Mclntosch, Sport in society (London, C.A. Watts, 1963), p. 75.

~~ 11 DV Coghlan, The development of athletics in South Africa (Unpublished Phd dissertation, Grahamstown, Rhodes University, 1986), p. 90.

12 P Dobson, Rugby at SACS (Cape Town, SACS, 1996), p. 11.

13 In 1905 the College Magazine carried an article, entitled, 'Athletics' that delt with football. Anon., "Athletics", Zonnebloem College. Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist 3(13) 1905, pp. 28-29.

14 Anon., "Thoughts on leaving Zonnebloem", Zonnebloem College. Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist 4(17) 1906, pp. 30-33.

15 PC McIntosch (Physical education in England since 1800, 1968), p. 46.

16 Anon., The encyclopedia of sports (London, Marshall Cavendish,1969), p. 27.

17 The Oxford and Cambridge cricket matches began in 1827 and the first boat race was held two years later (P.C. McIntosch, Sport and society (London, C.A. Watts, 1963), p. 66.

18 BGD Rudd, "Introduction", BGD Rudd, Athletics. The Achilles Club (London, JM Dent, 1938), pp. 3-4.

19 Anon., "Reminiscences of Bishop Gray", Zonnebloem College Magazine. Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist 3 (12), 1905, pp. 15-16.

20 The 'Kaffir' College, as it was known, formed part of Gray's funeral procession in September 1872 (HP Barnett-Clarke, "The life and times of Thomas Fothergill Lightfoot, Archdeacon of Cape Town (London, Simpkin & Marshall, 1908), p. 166.

21 JKH Hodgson, "A history of Zonnebloem College"..., pp. 1 ,253.

22 JKH Hodgson, "A history of Zonnebloem College"..., pp. 1, 251-252.

23 University of Cape Town Manuscripts and Archives Division. Zonnebloem papers, BC 636 D1.3 & F Cullis, The story of Zonnebloem, 1958. The Rev. Lightfoot, who visited the College in 1858 referred to the boys as Coloured children; HP Barnett-Clarke, " The life and times of Thomas Fothergill Lightfoot... p. 73.

24 JKH Hodgson, "A history of Zonnebloem College"..., p. 453.

25 Anon., "Native College, Zonnebloem", The South African Spectator, 24 August 1901, p. 1.

26 Anon., "Visitors", Zonnebloem College. Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist, 2(9), 1904, p. 17; JKH Hodgson, "A history of Zonnebloem College"... p. 558; Anon., "Native College. Zonnebloem", The South African Spectator, 24 August 1901, p. 1.

27 JKH Hodgson, "A history of Zonnebloem College"..., p. 223.

28 JKH Hodgson, "A history of Zonnebloem College"..., pp. 296-299.

29 JKH Hodgson, "A history of Zonnebloem College"., p. 223.

30 DH Craven & P Jordaan, Met die Maties op die rugbyveld, 1880-1955 (Kaapstad, Nasionale Boekhandel, 1955), pp. 31-32.

31 JKH Hodgson, "A history of Zonnebloem College"., pp. 453-456.

32 JKH Hodgson, Princess Emma (Craighall, AD Donker, 1987), p. 53.

33 B Johnston and D Stuart-Findlay, The motorist's paradise. Early motoring in and around Cape Town (St. James, RH Johnston and DM Stuart-Findlay, 2007), p. 3.

34 FJG Van der Merwe, Sportgeskiedenis. n Handleiding vir Suid-Afrikaanse studente (Stellenbosch, FJG, 1999), p. 219.

35 See FJG Van der Merwe, "A historical overview of Table Mountain as an icon for recreation in South Africa", African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 8(8) April 2002, pp. 94-105.

36 Lightfoot was influenced by Gray's "high character and personality" to take up missionary work in South Africa; HP Barnett-Clarke, "The life and times of Thomas Fothergill Lightfoot"..., pp. 13-14.

37 This is George Ogilvie, who was principal of St George's Grammar School at the time, became principal of the well known Bishops School in 1861 where he took boys on excursions; P Dobson, Bishops rugby. A history (Cape Town, Don Nelson, 1990), pp. 15-16.

38 Although Lightfoot smoked cigars, he abstained from getting drunk, maybe more so out of moral persuasion than for health reasons. On at least two occasions, while he was archdeacon, he "took home" intoxicated men; HP Barnett-Clarke, "The life and times of Thomas Fothergill Lightfoot"... pp. 8, 73, 80.

39 JKH Hodgson, "A history of Zonnebloem College"., p. 260.

40 JKH Hodgson, "Kid gloves and cricket on the Kei", Religon in Southern Africa, 8(2), July 1987, p. 68.

41 HP Barnett-Clarke, "The life and times ofThomas Fothergill Lighfoot..., p. 18.

42 HP Barnett-Clarke, "The life and times ofThomas Fothergill Lighfoot..., p. 21.

43 FJG Van der Merwe, Sporthistory. A textbook for South African students (Stellenbosch, FJG 2007), pp. 92, 100101.

44 JKH Hodgson, "Kid gloves and cricket" , Religon in Southern Africa, 8(2), July 1987, p. 71.

45 FR Baudert & T Keegan, Moravians in the Eastern Cape, 1828-1928. Four accounts of Moravian mission work on the Eastern Cape frontier (Cape Town, Van Riebeck Society, 2004), p. 48.

46 JKH Hodgson, "A history of Zonnebloem College"., pp. 534, 538.

47 CFJ Muller, Die oorsprong van die groot trek (Cape Town, Tafelberg, 1974), p. 166.

48 JKH Hodgson, "A history of Zonnebloem College"., p. 534.

49 JKH Hodgson, "A history of Zonnebloem College"., p. 264.

50 Anon., "Oscar Charles Hine.", 1944, p. 5.

51 Anon., "Editorial", Zonnebloem College. Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist 2(10), 1904, p. 2.

52 A Wieder, Teacher and comrade. Richard Dudley and the fight for democracy in South Africa (New York, State University of New York, 2008), p. 27

53 Anon., "Native games", Zonnebloem College. (Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist 2(11), 1905, pp. 12-14.

54 Anon., "Native College Zonnebloem", Zonnebloem Native College prospectus, 1904, p. 3.

55 Anon., "More play needed", Zonnebbem College. Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist 2(8), 1904, p. 14.

56 Anon., "More play needed"., p. 14.

57 Anon., "An ideal", Zonnebbem College Magazine. Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist 3(12), 1905, p. 13; Anon., "Speech Day", Zonnebloem College. Programme, 30 October 1913, p. 1.

58 Anon., "More play needed...", 1904, p. 14.

59 Anon., "Editorial", Zonnebloem College. Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist 2(8), 1904, p. 2.

60 Anon., "Native College Zonnebloem"..., 1904, p. 3;. Anon., "Oscar Charles Hine", Zonnebloem College Magazine, 1944, p. 5.

61 B Haley, " The healthy body and Victorian culture" (Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University, 1978), p. 4.

62 D Siedentop, Introduction to physical education, fitness and sport (Mountain View, Mayfield 1990), p. 69.

63 B Haley, "The healthy body and Victorian culture..", p. 168.

64 Anon., "Oscar Charles Hine"..., p. 5.

65 Anon., "Draft programme for the athletic sports", Zonnebloem College. (Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist3(13) 1905, pp. 28-29.

66 Anon., "Athletics", Zonnebbem College. Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist 2(9) 1904, pp.10, 16-17; Anon., "The College Sports", Zonnebbem College. (Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist 2(10), 1904, pp. 16-17.

67 Anon., "The College Sports"..., 2(10), 1904, p. 16.

68 Anon., "Draft programme for the athletic sports.", 3(13) 1905, pp. 28-29.

69 Anon., "Cape Town Gala Sports", Zonnebloem College. Quarterly Magazine and Journal of the Association of St. John Baptist, 5(28), 1908, p. 82.

70 M Adhikari, Against the current, p. 32. Cressy was one of the first people, regarded as Coloured, to obtain the BA degree, while Heneke was one of the first to obtain the MA degree (A Venter, Coloured. A profile of two million South Africans, Cape Town, 1974), p. 71.

71 Anon., "Athletics", Zonnebloem College, 2(9), p. 17; Anon., "The College Sports...", p. 16.

72 The first names were obtained from the Western Cape Education Department Education Conservation Centre in Aliwal Road, Wynberg.

73 See M Adhikari, Against the current. A biography of Harold Cressy, 1889-1916 (Cape Town, Juta, 2000).

74 Anon., "Cape Town Gala Sports...", 5(28), 1908, p. 82.

75 Anon., "Roll up, school", Educational Journal, 3(18), 1917, p. 2.

76 Sun The, Anon., "Old Trafalgarians and inter-school sport", 6 October 1933, p. 1.

77 Department of Basic Education. Republic of South Africa. Curriculum and assessment policy statement. (CAPS).History FET. Grades 10 - 12. Final.

78 P Seixas, "Teacher notes: Benchmarks of historical thinking. A framework for assessment in Canada" (Unpublished paper, University of British Columbia, Centre for the study of historical consciousness, n.d.), pp. 1-2.