Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.8 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2012

ARTICLES

Ghana, cocoa, colonialism and globalisation: introducing historiography

Helen Ludlow

School of Education University of the Witwatersrand helen.ludlow@wits.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The recently implemented curriculum for secondary History in South African schools - as set out in the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statements (CAPS, 2011) - presents no explicit statement of the view of history informing its construction. While it is clear that the development of historical skills is intrinsic to the stated intention of CAPS, this gap is problematic. This is because it leaves assumptions about the nature of history unaddressed. At the same time, historiography is difficult. This article asks whether, in tackling three CAPS sections of Ghanaian history - through the history of cocoa -learners could be introduced to historiography in a productive manner. It provides a sample narrative of Ghana's cocoa industry from the late 19th century onwards. It shows how the topic lends itself to an historiographical exploration which may be used to initiate learners into constructing their own narratives and in so doing, into engagement with historiographical issues.

Keywords: Ashanti; Gold Coast; Ghana; Cocoa; Colonialism; Globalisation; Historiography; Secondary history curriculum.

Historical thinking and secondary school history

This article represents some rather preliminary thoughts emerging from my engagement with future teachers of history; thoughts about whether there is a place for an explicit focus on historiography when teaching the secondary school History curriculum. Is there any value in secondary school students knowing that social history is different in essence from cultural history; that gender history is not just about adding on information about women, and that post-colonialism presents an essential view of western power as colonizing the mind? If so, how is that "knowledge" acquired in a way that does not simply confuse?

Before considering historiography, however, I would like to make a few more general points about teaching history. Thinking about history teaching leads to a consideration of the relationship that exists between sound content knowledge embedded in understanding of the processes of knowledge production, and sound methodology. The latter assumes an ability to transform an academic practice into schooled knowledge (Bernstein, 2000). The ability to make history teachable is both aided and complicated by the intervention of policy in the form of curriculum imperatives; in South Africa currently, the Content and Assessment Policy Statements (CAPS, 2011a, Social Sciences Senior Phase; 2011b, History).

There appears to be a wide recognition in teacher education circles that deep subject knowledge is necessary for effective teaching. But in addition to this, and over and above skilful techniques in the classroom, many educators are now being challenged to think about Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK). I watch with interest as my colleagues in the Wits School of Education Science and Mathematics subject areas explore the implications of notions of PCK. Lee Shulman describes PCK as "the particular form of content knowledge that embodie[s] the aspects of content most germane to its teachability", the "most powerful forms of representation" (http:// www.leeshulman.net). As I understand it, the educator identifies concepts crucial to the teaching of a topic, and spends time elaborating these through careful analogy or whatever is appropriate. Where, however, the sciences are able to narrow down the pedagogical content to a "make-or-break" central concept or key misconception in topics like the nature of light, the multiple, indefinable complexities of historical events or epochs make this impossible. So while detailed history content is important, the route to a deep knowledge of what history is about may be found through an engagement with the "epistemic tradition" of history. Through this, students can engage with the "forms, processes and structures of history" (Counsell, 2011: 207-217 as cited in Kallaway, 2012: 26). This is something that the work of a number of academics including Terry Hadyn, Tony Taylor, Sam Wineburg and Peter Seixas, on historical thinking, literacy and historical consciousness has begun to develop in some depth (Maposa & Wasserman, 2009).

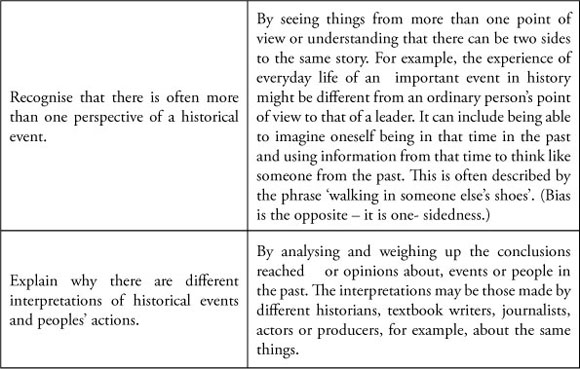

An examination of the "Skills and concepts of History" as set out in the CAPS documents (2011a: 11-12; 2011b: 12-13), shows that there is a strong correlation with what Seixas and others identify as the essential ingredients of historical thinking. (See Appendix 1: Seixas, History Thinking Project, point 5, https://historythinking/concepts). In the History CAPS for Grades 10-12 (2011b: 12), this is elaborated as learners having the skills to:

In the same curriculum document, under "Concepts", "multi-perspectivity" is presented as:

There are many ways of looking at the same thing. These perspectives may be the result of different points of view of people in the past according to their position in society, the different ways in which historians have written about them, and the different ways in which people today see the actions and behavior of people in the past (2011b: 13).

There can be no argument against the importance of developing the above skills and understanding, which includes looking at "the different ways in which historians have written about" the same thing. What I would like to present in this article, is a move from what could be narrow debates within a topic to a broader matter of interpretation  historiography. As Peter Kallaway (2012) notes in his discussion of CAPS, there is little within the policy documents that places the interpretation of the history that the CAPS contain within a wider historiographical framework. In Kallaway's view (2012: 26-29; 45), issues of race, nationality and a battle for human rights dominate the CAPS.

A dominant paradigm informing CAPS would thus be a form of social history that engages with economic power and subordination, inequity, racism and resistance. All of this, I would argue, is needed in a society still so palpably unequal. We do need a history of society and an historical consciousness that enables us to act (Eley, 2005; Seixas, 2009). The CAPS also embody a fairly traditional national history approach to political change. Finally, nods are made in the direction of the role of women (gender history), the role of the ordinary people (history from below), and representation and cultural practice (cultural history). The CAPS are not, however, inviting teachers and learners to engage directly with the matter of historiographical paradigms and, as the opening quotation suggests, creating a dialogue between different perspectives.

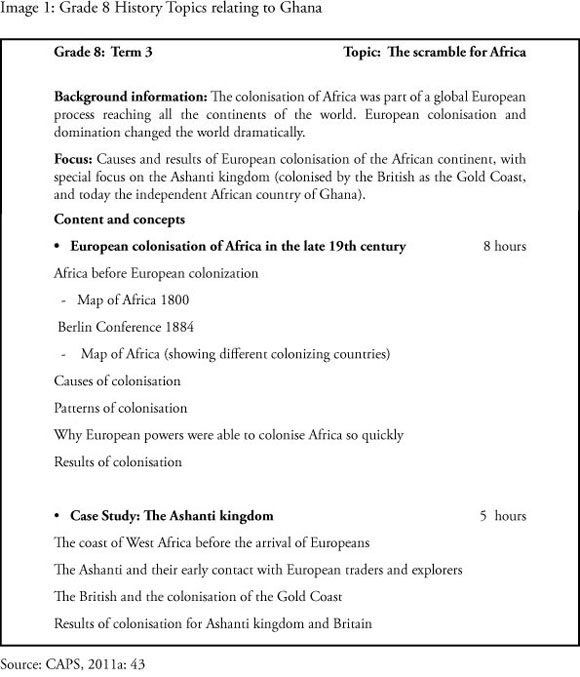

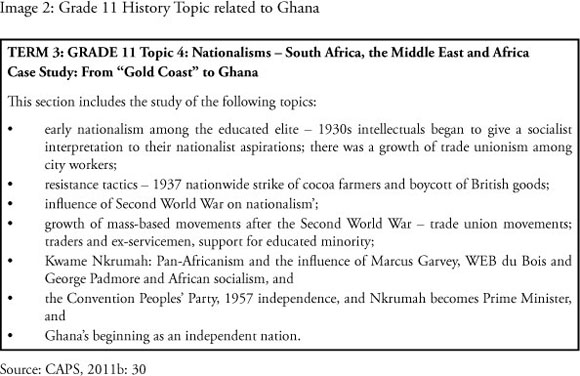

The purpose of the article is to provide a narrative through which it may be possible to explore historiographical issues. My focus is on Africa and I have selected three sections of the CAPS History curriculum dealing with Ghana (Images 1, 2 and 3 on pages 5, 10 & 11). The fascinating topic of cocoa is used as a way to enter into the content and key concepts of each curriculum section and, using for the most part well-known secondary texts, I construct a narrative of its history in Ghana. This does not pretend to be an exhaustive history and clearly it is my personal construction. The history of cocoa in Ghana is then used to introduce historiographical issues, essentially by asking the kinds of question that would emanate from historians who hold different views of history.

Ashanti, cocoa and colonialism Cocoa - early global connections

The cocoa tree, Theobroma cacao, is indigenous to the rainforests of central America. As far back as 600-400 BCE, societies in the Mayan area drank a bitter chocolate drink made from roasted cacao beans, spices and water. Cacao was seen as "a gift from the gods" and along with maize was believed to be the essence of life (Vail in Grivetti & Shapiro (eds), 2009: 4-10). Its consumption thus had strong religious and medicinal functions, while cacao was also used as currency (Grivetti & Shapiro (eds), 2009: xi).

It was through the 15th and 16th century voyages of exploration that Spanish conquistadors first encountered cacao in Central America and in 1528, Hernan Cortes first introduced it to Spain. Although it took the Spaniards some time to appreciate the charms of hot chocolate, a beverage very different from what we know today (Smith, Child & Rowlinson, 1990: 50-51), it was eventually produced in the seclusion of Spanish monasteries as a drink for the nobility (www.cadbury.com.au). At the same time the Portuguese created an important early global connection between Europe, Brazil and Africa through their voyages of exploration. They began large-scale cocoa production in Brazil which was to a large extent made possible by their acquisition of African slaves. In the 1820s, under the direction of the Portuguese crown, they also began to cultivate cocoa on the small Portuguese island possessions of Säo Tomé and Principe, off the coast of Africa in the Gulf of Guinea (Walker in Grivetti & Shapiro (eds), 2009: 547-550). It was probably from there that cocoa spread to Fernando Po, another nearby small island - initially Portuguese, later Spanish - and on to West Africa (Hallett, 1984). The Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors of the late 15th century were thus instrumental in creating transcontinental connections which resulted in a demand for cocoa in Europe which would be met increasingly in Africa.

By the 17th century the Spanish monopoly on chocolate was lost and knowledge of how to produce it spread to much of Europe. The social appeal of hot chocolate in England is evident in the emergence the chocolate houses, the forerunners of gentlemen's clubs, from 1657. Expensive because it was still processed manually, chocolate was a beverage for the elite who met to enjoy it (Gordon in Grivetti & Shapiro (eds.), 2009: 583-584).

Ashanti

The story of cocoa takes us to those sections of modern Ghana occupied by the Fante and other small coastal states and the interior Ashanti kingdom. West Africa had a long history of connection to trans-Saharan gold trade, and from the 15th century was drawn into trade with Europe; in gold and increasingly in slaves. The coastal states were most directly impacted by Portuguese, Dutch, and increasingly the British merchants (Ade Ajayi (ed) 2003: 265). To the north, the Ashanti kingdom had emerged from the mid-17th century, benefitting from access both to rich agricultural resources and gold, much of the labour for production of which was provided by a domestic slave trade (Iliffe, 1995: 143). By the late 1700s, with a bureaucracy based on merit and twenty subordinate tributary states, Ashanti was militarily powerful and one of the largest polities in West Africa. It reached its peak in the early 19th century, controlling most of modern Ghana. The golden stool and impressive golden regalia symbolized the power of the ruling asantehene (Ade Ajayi (ed), 2003: 264-265).

Colonialism

British traders had operated off what was to become known as the "Gold Coast" with little direct intervention by British authorities. After the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, however, it became the task of the British navy to enforce the embargo (Fage, 1979: 332). In so doing they began to negotiate treaties with African authorities, to force adherence and, finally in 1874, to subordinate the smaller coastal states in the interest of protecting trading interests there. When the Ashanti kingdom showed similar ambitions to expand its control southwards, the British invaded Ashanti in 1874 and burnt its capital (Ade Ajayi (ed), 2003: 266). British forces withdrew until a revival of Ashanti power and fear of competing French interests led Britain to proclaim a protectorate over all of modern Ghana in 1895/6. Initially avoiding outright war, the Ashanti nearly succeeded in driving out the British in 1900. But they ultimately failed and the empire was dismantled and a British protectorate over the Gold Coast established (Shillington, 1995: 309).

With the end of slavery came a growing concern amongst British traders to find "legitimate" commodities to trade and new markets for the products of the British industrial revolution. These included palm oil, ground nuts, cocoa and coffee, products in the 19th century which "were... most effectively produced and marketed ... by hosts of enterprising small men, who could respond freely and quickly to varying stimuli of work market forces" (Fage, 1979: 329). More cynically, other historians refer to the emergence of particular cash crops as introducing

dessert and beverage economies  economies which are based on crops like tea, coffee, sugar and cocoa for the dessert confectionaries of the Western world, while the African people themselves are short of such basic foods as grain, meat and root crops (M Owusu, in A Mazrui (ed), 2003: 317).

British colonial rule and cocoa arrived together. In 1879 a blacksmith, Tetteh Quarshie, took some cocoa seeds from Spanish Fernando Po home to the Gold Coast where, once planted, they flourished. By the 1890s, with the active support of the British administration, thousands of cocoa tree seedlings had been sold to local African farmers. From the Akwapim ridge, cocoa farmers migrated northwards into the relatively under-cultivated forest zone. There they bought land from local Akim chiefs and developed a thriving peasant-operated plantation system (Shillington, 1995: 337).

For these farmers, it took five years before the cocoa trees produced usable pods. Handpicked, the pods were then broken open with a baton so that the beans could be removed. These were covered in plantain leaves and left to ferment for three to nine days. They were then sundried for a week, usually on raised bamboo matting. At this stage the beans were packed and ready for sale (GlobaLink Africa Curriculum Project; www.cocoafederation.com) at coastal buying stations (Hallett, 1974: 330).

Iliffe notes that before the Second World War, colonial administrators "left the unfolding of economic affairs largely to private initiative". He sees the British authorities as similar to most colonial administrations at the time in contributing "only infrastructure, a legal system, and an appetite for taxation which drove their subjects into the cash economy" (1995: 202). This is not to deny that decisions about the location of infrastructure, land tenure policy and application of structures of indirect rule shaped the parameters of local initiatives, often adversely. An important decision that did benefit local producers, one made under local pressure, was not to allow the sale of "African" land to any Europeans and so the production of cocoa in the Gold Coast remained in African hands, mostly on smallholdings (Shillington, 1995: 347).

Why Cocoa?

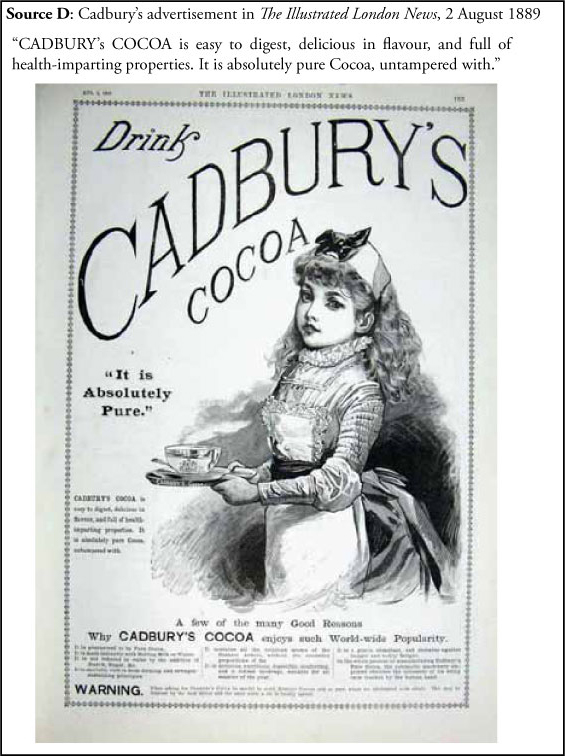

With industrialization in 19th century Europe and increasing commercialization of chocolate production came the "democratization" of chocolate. The mechanization of chocolate production became possible in the 19th century, beginning with the invention of new cocoa presses (by the Dutch in 1828, the British in 1866). This made chocolate in its various forms more affordable, and the emergence in Britain of Quaker companies  Fry's, Cadbury's and later Rowntrees - expanded the demand for West African cocoa. So, too, did the establishment of Hersheys in North America by 1900. The late 19th century and early 20th century saw Swiss chocolate manufacturers (such as Callier, Kohler and Nestlé) dominating the market after the invention in 1876 of milk chocolate by Daniel Peter (Gordon in Grivetti & Shapiro (eds.) 2009a: 576; 2009b: 587-591).

Cocoa and social change

"Cocoa is Ghana, Ghana is Cocoa" (Ghanaian saying, cited in Ryan, 2011:10).

By 1911, the Gold Coast was the world's greatest producer of cocoa (Iliffe, 1995: 203). As production spread northwards, the Ashanti chiefs also became cocoa producers and the Ashanti region became a dominant producer (Cocobod statistics of regional purchases for 1947-1957, http://www. cocobod.gh/weekly_purchases.php). In the 1920s, some 200 000 tons of cocoa was exported from the Gold Coast annually (Hallett, 1974: 328). The manufacturers of cocoa products did not generally go to the source themselves, but bought cocoa from European trading companies. Until the 1930s, these merchants depended on thousands of African brokers and sub-brokers "to bring the export crops to their buying stations" on the coast (Hallett, 1974: 330).

Cocoa production earned many farmers a measure of prosperity; this to be spent after taxes, on building of homes, infrastructure and on mission education (Shillington, 1995: 337). A number also formed co-operatives. Maxwell Owusu notes of African peasantries that "the extent of poverty and prosperity. at any given time has varied a great deal from country to country and from region to region" (in Mazrui (ed) 2003: 340). By the time of its independence as Ghana in 1957, the Gold Coast was regarded as one of the most prosperous colonies. Yet there was much that hindered the progress of rural producers in a country whose "economy became an extension of that of the colonizing power" (Adu Boahen (ed), 2003: 159). Firstly there was the dependence on external markets for cocoa, the prices for which lay outside of producers' control. Secondly there was a growing dependence on imported tools, the costs of which were also outside of producers' control (Shillington, 1995: 350).

The shift to cash crop production also changed social relations (Iliffe,1995: 216). Increasingly farming took place in nuclear family units rather than on communal farms belonging to the extended family. Individual wealth led to openings in government, education and politics (Ryan, 2011: 10 ). In time divisions emerged between rich and poor peasants and the use of seasonal migrant workers also became a common practice. Women, although still providing much of the labour, became more marginalized in decision making around the production and marketing of agricultural products. As foreign buyers, marketing boards and access to credit became more important, men were favoured as commercial partners (Owusu, in Mazrui (ed), 2003, 319320).

Space does not allow a fuller exploration of the vicissitudes of cocoa farming in Gold Coast during the colonial era, but the move to state regulation of marketing in response to peasant resistance is important. The strategy of holding back produce was used by farmers during World War I when prices fell sharply, and again in the 1930s during the world-wide depression (Adu Boahen (ed), 2003: 182). In 1937 the British colonial government undertook to buy all the cocoa from smallholders, formalizing this process through the West African Cocoa Control Board (Cocobod) in 1938. What was presented as a way of securing a reasonable price for farmers turned into a strategy for raising state revenue through buying low and selling high. While farmers were unable to negotiate prices, the big companies retained a strong influence over the Cocoa Board through quotas allocated by government, and John Cadbury was chair of the Board for some time (Lappé & Collins, 1977: 99-111).

In justification of its intervention, the state, especially after World War II, committed itself to a developmental programme. Revenue from taxes and cocoa sales were used for projects in transport, technical services and education (Fage, 1979: 417-420; Cooper, 2002: 67). According to Fage (1979: 418), "With the price of cocoa in the early 1950s ten or more times what it had been in the 1930s" all but £3million of the original £75 million cost of this development plan could be funded locally. In fact cocoa revenues from the Gold Coast were even used to prop up the Allied war effort.

Nationalization, globalization and cocoa

The harsh realities of post-war socio-economic conditions fueled mass support for Gold Coast African nationalist campaigns after World War II. The emergence of well-organised political parties and a charismatic leader in the person of Kwame Nkrumah assisted this. At the same time the British government recognized, in face of decolonization elsewhere in its empire, that they would have to move towards independence in Africa (Suret-Canale & Adu Boahen in Adu Boahen (ed.) 2003: 171).

Fred Cooper (2002: 67) notes that for Nkrumah, cocoa revenues raised by the Cocobod continued to be important for state development. On his ascent to power in 1957, the grip of Cocobod on pricing and marketing of cocoa remained firm, while political opposition from Ashanti cocoa farmers was crushed in the cause of national unity. At the same time little was done to sustain cocoa production when rapidly falling world cocoa prices added to discouragement. Nkrumah focused instead on prestigious construction programmes. These costly capital-intensive projects and his increasing despotism ultimately led to his downfall in a military coup in 1966. By this time, Cote d'Ivoire had overtaken Ghana, deeply in debt, as the world's premier producer of cocoa (Shillington, 1995: 413).

After 1966, Ghana experienced multiple changes in government and in economic policy. Seizing power in 1979, President Jerry Rawlings was in due course persuaded that cocoa was vital to securing foreign exchange and essential commodities (Ryan,2011: 19-20). His government thus came to embrace the policies associated with post-Cold War globalisation: democracy, structural adjustment guided by the World Bank and IMF, and a more liberalized economy (Cooper, 2002: 163). By 1995, the bloated Cocoa Board, whose executives made more out of cocoa than did the farmers, "employed roughly one-tenth of the 100,000 people it had employed a decade earlier. Farmers, newly motivated by rising prices began to plant cocoa. Production began to rise" (Ryan, 2011: 20).

Ghana was however unable to escape the pressures of operating in a competitive and fluctuating world cocoa market. This, as well as widespread poverty in the region, is probably why West African cocoa has recently become a human rights issue. The accusation that Ivorian and possibly Ghanaian cocoa farmers are cutting costs by using child labour has been the focus of a vigorous international campaign carried out on the internet, a most global form of communication. See, for example, the article, "Slavery in the Chocolate Industry", which alleges that the "farms of West Africa supply cocoa to international giants such as Hershey's, Mars and Nestlé -revealing the industry's direct connection to child labour, human trafficking and slavery" (www.Foodispower.org). Orla Ryan, likewise, in her recent book Chocolate nations: living and dying for cocoa in West Africa, alleges that, beyond the comforts of the confection, there are severe hardships for producers of which no consumer should be ignorant.

Historiographical possibilities raised by the history of cocoa

The application in the secondary school History classroom of the skills and concepts highlighted by CAPS above would lead to classroom debate on historical matters, but they might be in a context of major silences - a silence, for example, on the construction of power on the basis of gender, or the absence of non-western representations and voices in debates about the very people under discussion. There may be lost opportunities to grasp the potential of historical investigations of identity and ideas, and their intriguing representation in categories like dress, landscape, space and consumer items.1 The misconception that there is only one approach to history, albeit one with strong roots, could leave teachers and learners with a false sense of confidence that they know what history is and are in control of the "true" version.

I would like to picture a group of historians contemplating the above overview of the history of cocoa with particular reference to Ghana. And I would like to invite teachers and learners to sit in on their conversation. What are some of the questions the historians might raise about this narrative? For the cultural historian, it could be, "What is and was the meaning of chocolate for different groups of people at different times and places?" The gender historian would no doubt point out the very limited exploration of gender roles and identity, and might ask, "How can we overcome the silences in this very male history?" With their roots in Marxist class analysis, both the social and postcolonial historian would be happy with suggestions that the production of cocoa for global markets has been exploitative. The first might ask, though, "How can we discover more about the everyday life of peasant producers?" The latter could inquire, "What about the mental worlds of the colonized subjects? How do we understand these?" With this, the cultural historian would agree. The dependency theorist would ask for "more rigorous exposure of the exploitation of Ghana within the capitalist colonial and postcolonial systems of production". The Africanist might be celebrating the acknowledgement that Ashanti as evidence of a rich African history before colonialism, and ask, "Isn't the enterprise shown by Gold Coast peasant farmers a sign of African agency rather than passive exploitation?" Our post-modernist would decry the whole narrative as fictional and ask, "Whose story is this?"

For historiography to become a meaningful concept for learners, the teacher needs to be an informed mediator. 2 The task then becomes to raise issues and pose questions which help learners to see that historical accounts are not neutral and the work of historians can be fitted into certain paradigms. The paradigms themselves are obviously constructions and interpretations, but as the work of Laura Lee Downs (2010) shows, shifts in historiography are contextually based. African historians and woman historians, for example, have raised issues specific to contexts of exclusion.

It is probably over ambitious to attempt to do more than alert secondary school students to historiographical issues, but a process could begin with a conversation based on the text of this article. Questions such as the following could be posed:

Why do you think the historians are asking these particular questions?

What do their questions tell you about their own interests and concerns?

Can you suggest anything about the historians' backgrounds that could make them ask these questions?

Which questions interest you most?

How could you find out more about different schools of history?

These questions could be followed by engaging learners in articulating - orally or in writing - their own brief narratives from a particular historiographical position. I have included a couple of suggestions in Appendix 2. Ideally, over time, there would be opportunities for them to research more fully and then debate topics from particular standpoints. To begin to understand how and why historians write from different perspectives is probably, I would argue, more important than being totally correct about which historian fits into what school. The issue is to enlarge historical understanding.

References

Ade Ajayi, JF (ed.) 2003. UNESCO General history of Africa VI: Africa in the nineteenth century until the 1880s, abridged ed. Glosderry, South Africa: New Africa Books. [ Links ]

Adu Boahen, A (ed.) 2003. UNESCO General history of Africa VII: Africa under colonial domination 1880-1935, abridged ed. Glosderry, South Africa: New Africa Books. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B 1996, 2000. Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity, theory, research, critique. London: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Cooper, F 2002. Africa since 1940: The past of the present. Cambridge: CUP. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2011a. Curriculum and assessment policy statement, Social Sciences Senior Phase. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2011b. Curriculum and assessment policy statement, History. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Downs, LL 2010. Writing gender history 2nd ed. London & New York: Bloomsbury Academic. [ Links ]

Eley, G 2005. A crooked line: From cultural history to a history of society. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

Fage, JD 1979. A history of Africa. London: Hutchinson. [ Links ]

Gordon, BM 2009a. Chocolate in France: Evolution of a luxury product. In: Grivetti, L and Shapiro, H-Y(eds.) Chocolate: History, culture and heritage. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. [ Links ]

Gordon, BM 2009b. Commerce, colonies, and cacao: Chocolate in England from introduction to industrialization. In: Grivetti, L and Shapiro, H-Y (eds.) Chocolate: History, culture and heritage. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. [ Links ]

Hallett R 1974. Africa since 1875: A modern history, 2. London: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Iggers, GG & Wang, QE 2008. A global history of modern historiography. Harlow, England: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Iliffe, J 1995. Africans: The history of a continent. Cambridge: CUP. [ Links ]

Kallaway, P 2012. History in Senior Secondary School CAPS 2012 and beyond: A comment, Yesterday & Today (7): 23-62. [ Links ]

Lappé, FM & J Collins 1977. Food first: Beyond the myth of scarcity. New York: Random House. [ Links ]

Owusu, M 2003. Agriculture and rural development since 1935. In: Mazrui, AA (ed.)

UNESCO General history of Africa VIII: Africa since 1935, special ed. Glosderry, South Africa: New Africa Books.

Ryan, O 2011. Chocolate nations: Living and dying for cocoa in West Africa. London & New York: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Seixas, P 2008. Introduction to Historical Thinking. In: Panel on "What is the shape and place of historical thinking in high schools?" Association for Canadian Studies Conference, 24 October 2008. Available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=WpH-uEbT3ds. Accessed on 3 September 2012. [ Links ]

Seixas, P 2012. The Historical Thinking Project. Available at http://historicalthinking/ concepts. Accessed on 3 September 2012. [ Links ]

Shillington, K 1995. History of Africa, revised ed. London: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Shulman, L 2008. The work of Dr Lee Shulman. Available at http://www.leeshulman.net/ domains-pedagogical-content-knowledge.html. Accessed on 11 September 2012. [ Links ]

Smith, C, Child, J & Rowlinson, M 1990. Reshaping work: The Cadbury experience. Cambridge: CUP. [ Links ]

Stearns, P, Seixas, P & Wineburg, S 2000. Knowing, teaching and learning history: National and international perspectives. New York: NYU. [ Links ]

Vail, G 2009. Cacao use in Yucatan among the pre-Hispanic Maya. In: Grivetti, L and Shapiro, H-Y (eds.) Chocolate: History, culture and heritage. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. [ Links ]

Walker, T 2009. Establishing cacao plantation culture in the Atlantic world. In: Grivetti, L and Shapiro, H-Y (eds.)Chocolate: History, culture and heritage. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. [ Links ]

Wineburg, S 2001. Historical thinking and other unnatural acts. Philadelphia: Temple. [ Links ]

Electronic References

Discovering Chocolate. Available at http://cadbury.com.au/AboutChocolate/Discovering-Chocolate.aspx. Accessed on 8 November 2012. [ Links ]

Federation of Cocoa Commerce. An overview of cocoa production in Cote d'Ivoire and Ghana. Available at http://www.cocoafederation.com/education.produce.jsp. Accessed on 10 September 2012. [ Links ]

FoodIsPower.org. Slavery in the chocolate industry. The Food Empowerment Project. Available at http://www.foodispower.org/slaverychocolate.htm. Accessed on 11 May 2012. [ Links ]

Ghana Cocoa Board. Regional Cocoa Purchases. Available at http://www.cocobod.gh/weekly_purchases.php. Accessed on 10 September 2012. [ Links ]

GlobaLink-Africa Curriculum Project. Africa and globalisation. Available at http://www.globalisation-africa.org. Accessed on 25 May 2010. [ Links ]

Historiography is a continuous dialogue, always marked by new perspectives which enrich the understanding of the past but which themselves are replaced by other perspectives (Iggers & Wang, 2008: 329).

1 See for example F Trentmann (ed.), The Oxford handbook of the history of consumption (Oxford, OUP, 2012), the blurb for which claims: "The Handbook ... showcases the different ways in which recent historians have approached the subject, from cultural and economic history, to political history and technology studies, including areas where multidisciplinary approaches have been especially fruitful."

2 Three useful resources on historiography are G Eley, A crooked line: From cultural history to a history of society (Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 2005); GG Iggers & QE Wang, A global history of modern historiography (Harlow, England, Pearson Education, 2008); LL Downs, Writing gender history, 2nd ed. (London & New York, Bloomsbury Academic, 2010).

Appendix 1:

Key concepts for Historical Thinking: The Historical Thinking Project (http://historicalthinking/concepts)

1. Establish historical significance

2. Use primary source evidence

3. Identify continuity and change

4. Analyze cause and consequence

5. Take historical perspectives, and

6. Understand the ethical dimension of historical interpretations.

Appendix 2:

Activities related to Cocoa Production in Ghana through which to explore historiographical viewpoints

1. Using the Cadbury’s website (http://cadbury.com.au/AboutChocolate Discovering-Chocolate.aspx), write a short account which praises the enterprise and achievement of this family business. In this you should take a (liberal) position in which capitalist enterprise and free trade are supported.

2. Consult T. Walker 2009. Establishing cacao plantation culture in the Atlantic world. In: Chocolate: History, culture and heritage, ed. Grivetti, L and Shapiro, H-Y, 543-558. This can be accessed online. Use the information in this chapter to explain the early global connections between Brazilian and West African cocoa farming. Speak from the point of view of a historian whose interests are in promoting an understanding of the global connections of capital, and of how it has always been exploitative.

3. How do Source A and Source B below differ in explaining the emergence of the cocoa industry in Gold Coast? Can you suggest why Adu Boahen’s version is sees as “Africanist”?

Source A:

“Contrary to what colonial historians would have us believe, the peasant export sector in [West Africa] was established with little government initiative. Even the Gold Coast cocoa industry, of which the British were greatly proud, was essentially developed with local initiative. Starting from almost nothing in the early 1890s, by 1903 the famers had put over 17 000 ha under cocoa. By 1928 there were 364 000 ha of cocoa, and in 1934 the Gold Coast produced 40% of world output. Yet until this time the industry had benefited little from scientific research carried out in the country.”

A Adu Boahen (ed.)2003. UNESCO General history of Africa: Africa under colonial domination 1880-1935: 178.

Source B:

“Although the opinion is widespread in Portuguese popular historic literature that cacao was introduced into the tiny West African colonial islands of São Tomé and Príncipe - and subsequently the rest of Africa - by happenstance, as an ornamental plant and not as part of a deliberate commercial endeavor, the truth is plain in Portuguese colonial correspondence of the early 19th century. In fact, just a few years before Brazil won its independence (1823) ... the Portuguese monarchy ordered the transplant of cacao seedlings from Brazil to São Tomé and Príncipe.”

T Walker 2009. Establishing cacao plantation culture in the Atlantic world. In: Grivetti L & Shapiro, H-Y (eds.) Chocolate, culture and heritage: 549.

4. A concern of gender historians is to show how power relations affect women. Note this in the extract from Maxwell Owusu, Source C. Find the ways in which women have lost the control over farming which they had before the production of cash crops like cocoa in Gold Coast/Ghana became so important.

Source C:

“[A] major distortion in the legacy of colonial agriculture was the male bias. Much of traditional African agriculture had involved women. Indeed, women were often the majority of farmers in African societies. The colonial impact did not end the numerical preponderance of women, but it did contribute to their marginalization. In the traditional setting, women had considerable say in determining the value of commodities. With the coming of the cash economy, women could still be the main determinants of prices for the local market in the hustle and bustle of conventional bargaining and exchange. But a number of colonial changes helped to shift the balance in favour of the men .... One factor consisted precisely of the marketing boards [whose staff] were overwhelmingly male. ... [B]etween the producer and the consumer were [male dominated institutions which also] marginalized women...

A related aspect concerns the internationalization of African economies. The traditional local economies gave women considerable [ability to regulate] the processes of exchange. But as soon as African economies demanded distant contacts with buyers in Japan, Europe and the America, the boards of directors of African farms consisted overwhelmingly of men.

The modernization of agriculture has also increased the role of credit facilities for the purchase of seeds, fertilizers, equipment and for the construction of storage facilities. The expanding role of credit, in both the colonial and post-colonial periods, has often resulted in the expanding role of men. Partly because of indigenous constraints on women owning land, and partly because of more universal banking prejudices concerning the credit-worthiness of women, monetized agriculture in Africa has contributed to the marginalization of the female cultivator.

The very promotion of cash crops has helped the male bias in African agriculture. African women were often in control of the cultivation of yam, cassava and maize... On the balance, cash-crop cultivation has tilted the balance in favour of male labour.

What is at least as significant is the managerial shift in favour of men on issues of cash crops. Decision-making about traditional food production allowed for a much bigger female role than decision-making about cash crops. Production, processing, pricing and export functions in cash crops have basically been taken over by men.”

Maxwell Owusu (in A Mazrui (ed.)2003. Africa since 1935: 319-320).

5. Historians who write New Cultural history focus on how peoples’ ideas and identities are shown in how they represent themselves, what they value and through their practices.

5.1 What does Source D tell us about who Cadbury’s hoped to appeal to in the 1800s?

5.2 What does Source E tell us about what chocolate means to a young Ghanaian today?

(Remember that the cocoa he helped to produce could well go to Cadbury’s who still use Ghanaian cocoa for their products.)

Source E:

“For 16-year-old Alhassan Ali, work on a cocoa farm presented a chance to make a better life for himself. Encouraged by his mother, he left his home ... in northern Ghana in search of work when he was 14. ... ‘I was hungry, I wasn’t in school. I came on my own, nobody came for me.’... In the week before we met, Alhassan had just finished breaking cocoa pods and putting beans to dry on woven trays. He had no idea what these beans are used for and has never tasted chocolate. All he knows is that the government buys them.”

O Ryan 2011. Chocolate nations: Living and dying for cocoa in West Africa: 56-57.

6. Geoff Eley, in his book, A crooked line: From cultural history to a history of society, is concerned that historians should write history which tackles important social issues. Watch the film, “The Dark Side of Chocolate” directed by Roberto Romano. (It is accessible online). Discuss the place, if any, of this emotive documentary, in the history of cocoa in West Africa.