Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Yesterday and Today

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9003

versión impresa ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T no.5 Vanderbijlpark ene. 2010

ARTICLES

The value and role of cemeteries: designing a possible methodology for teaching heritage to history learners

Pieter Warnich

Dr. Potchefstroom Campus. North-West University. pieter.warnich@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Teaching heritage to History learners is imperative as an aid to help them discover their uniqueness but also their commonalities. A sense of heritage does not only contribute to a feeling of belonging and identity, but also promotes social cohesion, mutual understanding and unity in a multi-cultural, multi-national country. Due to its perceived value, heritage as a theme is recognised as one of the knowledge focuses for History as prescribed in the National Curriculum Statement. However, for various reasons, heritage does not receive the attention in the teaching and learning of History it deserves. By concentrating on the value and role of cemeteries, the purpose of this article is to provide History teachers with a step-by-step methodology in support of the effective teaching of heritage.

Keywords: History teaching and learning; Heritage; Cemeteries; History methodology; History education.

"We construct meanings from the heritage and we construct ourselves from it as well." (David Uzzell, 2009)

Introduction

Teaching about heritage links History learners to the historical reality of the world around them and the influence of the past on the present. Through heritage teaching, learners discover their uniqueness as well as their common ground, and in this manner it promotes social cohesion, mutual understandinand unity.1

Although many publications that investigate heritage as a phenomenon are the order of the day, scant attention is paid to the range of methods that can be utilised to investigate the varied dimensions of heritage, and how interpretations can be constructed from the scope and nature of the available data.2

The aim of this article is to investigate the role and value that cemeteries can play in designing a possible methodology for History teachers to teach at heritage sites where learners can learn firsthand. Cemeteries provide an enormous amount of concrete and credible data that can shed light on the social, economic and political status of a community or local area. To undertake a teaching and learning experience at a local heritage site is socially constructive by nature and therefore in accordance with the aims of the Outcomes-based Education (OBE) model.3 Based on enquiry and problem-solving activities, teaching and learning about heritage are activity-based and learner-centred. Learners become the active agents in their own learning when investigating gravestones as primary sources. When investigating heritage, learners will develop important skills that will aid them to remake the past and enable them to (re)define and identify future heritage. In this way on-site heritage studies can be seen as a dynamic process with future implications for lifelong learning.4

Heritage conceptualised

Heritage is a broad, multi- and interdisciplinary field of study that can be used in different contexts.5 When considering the roots of the word "heritage", it originates from the Greek word klerosomos, meaning to obtain by inheritance.6 The concept of heritage can thus be seen as something valued that is transmitted or handed down from one generation to the next for safekeeping. What one generation wants to retain and pass on to future generations can include various things, for example: monuments, buildings, sites, landscapes, indigenous knowledge systems, cultures, symbols, customs, traditions, languages, artefacts, architecture, spiritual practices, values, art, literature, music, oral traditions, etc.

Heritage can also be constructed when the past is interpreted for the creation and reinforcement of "new" group identities on which future expectations can be built.7 Thus, by its very nature, the concept of heritage values the past and is concerned with the manner through which the past is constructed in the present for the future.8

Today most people associate the concept heritage with two related sets of meanings. On the one hand it is linked with tangible sites and/or artefacts of historical interest that have been preserved for the nation.9 As such, Macdonald10 identifies heritage as a "physical proof" or "material testimony of identity". On the other hand, heritage can also be associated with a set of inherited shared values and collectives memories that are articulated in separate languages and through certain cultural activities and performances.11

From the aforementioned it is clear that heritage is more than just the representation of tangible physical remains. It can also manifest diverse intangible symbolic and spiritual meanings that are often grounded in the material and tangible remnants of the past. These meanings will unavoidably be influenced by an individual's attitudes and behaviour, which are normally based on personal perceptions and subjective sentiments with regard to collective social memories. When heritage is contextualised in this way, it is socio-psychological in nature, showing the concept's multi- and interdisciplinary nature.12 Apart from the sociological and psychological nature of heritage, it is also the meeting place for various other disciplines like history, geography anthropology, archaeology, architecture, art and tourism.13

However, it must be mentioned that the term "heritage" is not a totally new concept that made its appearance with the phasing in of the new education model of OBE in 1998.14 In fact, in the history curricula of before this time, the heritage aspect in the teaching and learning of history has often been addressed by the related term "local history".15 By means of "local history", learners were introduced to their immediate geographical surroundings where the history of, for example, street names and landmarks, a local church, a cultural movement, battle sites, forts or monuments was investigated.16 The goals of, for example, the 1985 history syllabus refer to the necessity of learners to develop a love not only for their "own culture, nation, community, party, etc", but also to have an "understanding and appreciation" for other cultures.17 Although the concept heritage represents a more holistic meaning than local history does, Jackson18 is rightly of the opinion that local history and heritage share a common platform and are therefore in essence inextricable linked to each other. The local history of a community within a particular geographical area ensures not only knowledge and insight regarding their own history, but it also co-determines their orientation with regard to the place and role that the community played in the national and even international history.19 The fact that local events often relate to national and world events brings learners to the realisation that a local community did not develop in isolation, but that in reality it forms part of the greater picture.20

Heritage and the National Curriculum Statement (NCS)

Unlike most European countries where the theme of heritage is not always recognised as an integrated part of the subject of history,21 in South Africa it is embedded in much of the core content that is prescribed in the NCS. Already in the Foundation Phase (Grades R-3) heritage is reflected in the knowledge focuses for History (as part of the learning area Social Sciences) where it is expected of learners to, amongst others, tell stories about their own lives and the lives of their families. These learners must also be able to share their social experiences, which are peculiar to their particular culture group's food, clothing, games, toys, music, dance and works of art. Besides this, knowledge must also be demonstrated regarding national symbols, places of historical interest and stories about different historical events that are being celebrated. Learners are also afforded the opportunity to do narratives on topics and personal possessions that they cherish.22

For the Intermediate Phase (Grades 4-6), much emphasis is placed on the history of the province, the district and local area. In this regard the concepts "heritage and identity" as such are also specified in the NCS for Grade 5 learners for the first time. Heritage furthermore also appears in the study that deals with the early South African societies and the role and influence that African societies had on South Africa. In this phase the learners are also encouraged to construct a school or community archive and to complete a project that is based on oral history.23

In the Senior Phase (Grades 7-9), heritage is, amongst others, reflected in the early hominid discoveries in South Africa, the development of man in Southern Africa and rock art as a communication medium of the hunter-gatherers. Other themes in the NCS that address heritage in some or other way are: The Dutch settlement, the Indian Ocean slave trade, slavery at the Cape, the conflict between the different races at the eastern and northern border of the Cape, the influence of industrialisation and British colonialism on South Africa, apartheid and the human rights struggle.24

For Grades 10-12, heritage as theme is taken a step further in that it is set as a fourth learning outcome in the NCS. In the assessment standards of the Grade 12 "heritage" learning outcome, reference is even made to "grave sites" as a heritage memorial. Learners in this Further Education and Training (FET) Band are further compelled to do a heritage investigation during each of these three grades. Together with six other tasks, the heritage investigation forms part and parcel of the learner's continuous and formative formal programme of assessment, which will contribute 25% of the learner's total end-of-the-year mark for History. Through this heritage investigation, the learners will engage in critical and reflexive thinking about problem-solving issues, ideologies and debates around heritage, public representations of the past and the conservation and appreciation of local and national heritage. The ways in which the past is memorialised in archaeology, oral history and different knowledge systems, and how it contributes to an understanding of heritage, will also be explored.25

Besides the fact that, in the assessment prescripts, History teachers are compelled to complete a heritage task with the Grade 10-12 learners, it would seem that heritage as theme does not receive the attention it ought to deserve in all the other grades. There are several reasons for this. One of the reasons is that learners cannot always afford it financially to undertake a trip to heritage sites. In some instances teachers also find it difficult to make sufficient time available to plan and execute excursions to heritage sites in an already overstretched curriculum. At many schools it is the poor quality or the total absence of proper source material that prevents teachers from teaching heritage effectively in the classroom. The distinctive ethnical cultures of the learners also make it difficult for some teachers to disclose sound understanding and knowledge of everyone's heritage in class.26 In order to teach heritage properly, it requires of teachers to have a reflective, critical, sensitive and imaginative disposition.27 This disposition is often curbed because teachers do not always dispose of proper training in the methodologies suitable to teach heritage. In this regard, a few Grade 10 History teachers expressed a wish during a survey in 2006 that they would like to receive more training in oral history, to teach heritage and assessment, heritage assignments and heritage site visiting.28

The value of local cemeteries as heritage sites

The value of researching local cemeteries is that it reveals the public face of the people of a community or local area. Gravestones can reveal an abundance of information on earlier inhabitants who played a role in a specific community or particular area. Important personal information of the deceased can be seen on gravestones, such as names and surnames, dates of birth and death, the reason of death, the trade and occupation and country of birth. Other data that gravestones further reveal is infant and child mortality rates, the size of families, the effects of epidemics and the impact of war, the name of the stonecutter, the types of stone used in the head and footstones, the nature of the epitaph, the types and styles of the carving and lettering and the motifs used for the tombstone design. These are all valuable primary and tangible source evidence that supports the learning and teaching process by adding on more information to the written word in textbooks and the teachers' oral explanations in class.29

The combination of the concrete outside world and the inside of a classroom leads to a more personal experience with the learning material. Learners will not only gain an awareness of the actual texture, size, shape and weight of the gravestones, but the information on the head and footstones will also help them to a better understanding of the past. Research in local cemeteries creates numerous opportunities for group and enquiry-based activities where learners will gain knowledge on how to collect and classify their own research information, how to handle absences in data and negotiate contradictions. In this process they will acquire and demonstrate valuable historical skills when analysing, interpreting, synthesising and evaluating the relevant data.30 All these skills will in the end significantly broaden the learners understanding of history as a discipline and allow them to see themselves as apprentice historians.31

The value of "doing" heritage in local cemeteries helps learners to become more aware of the contribution that each culture group made in the inception and development of their community. This awareness helps learners to develop a more inclusive and common sense of belonging with regard to the people in his/her particular community or local area. By realising the contribution that each culture group made to the community, it will further enable learners to evaluate the wider issues and affairs of the country's history with more knowledge and deeper insight.32

The value of local cemeteries as heritage sites furthermore lies in the fact that it exposes learners to history's interrelationship with oral history and other subject disciplines such as geology, geography, archaeology, genealogy and tourism.33 An interdisciplinary teaching and learning approach has, amongst others, the advantage that it can answer complex research questions by offering solutions that are not usually within the scope of one subject discipline. Other advantages are that it addresses broad issues, which in turn can give rise to new and wider perspectives that can be opened on a particular historical event.34

The planning and preparation for a visit to a local cemetery

Administrative and logistical

As for any excursion, thorough planning and preparation for a visit to a local cemetery determine the success thereof. In the first place there are certain administrative and logistical arrangements that must be made. This can concern matters such as:

• obtaining the necessary permission from the principal and the cemetery authorities (some cemetery grounds are closed for day visitors);

• the composition of an accurate register of all the learners that will partake in the visit;

• the duration of the visit for the information of the parents and colleagues;

• date and time of departure and arrival;

• clearance from parents on the ethical aspects when cemeteries are visited;

• the signing of indemnity forms by the parents;

• appropriate provision and support for learners with special needs;

• contact numbers for the school and parents to contact in case of emergency;

• the appropriate stationary and other equipment (including a first aid kid); and

• enough staff to accompany the learners during the visit.35

With regard to the last point above, the teacher in charge of the excursion can consider arranging the visit at that time of the year when his/her school is visited by student teachers. Some of these students can take over the teacher's classes at school while some of the others can act as facilitators during the excursion.

Teacher-learner

It is important that the visit to a cemetery is not just seen as a pleasure trip where no "work" will be done. Therefore, well planned structured activities are essential, which must be designed by the teacher and the learners before the time. These activities must entail more than merely the perfunctory observation by the learners, and the teacher giving a lecture-style presentation.36 The planned activities must rather pursue an interactive and learner-centred approach of the "do" of heritage where the teacher acts as facilitator of the learning action.

As a first step in the planning and preparation, it is essential that the teacher should make certain of the history of the particular region in which the local community sorts. This knowledge will not only provide the teacher with a total picture of the most important events, it will also enable him/her to distinguish what was peculiar or unique to the particular community and which events are shared with other communities on national level.37 As point of departure, this knowledge can then be used to orientate the learners prior to the visit in respect of the place and role that cemeteries play in the history of their community in the further disclosure or support of the already existing historical facts.

A second step in die teacher-learner planning and preparation is to formulate clear learning outcomes and assessment standards that need to be attained with the visit to the local cemetery. Once the teacher has decided who the assessment agent(s)38 is going to be, attention must also be paid to the design of the assessment criteria in order to assess the learning product. With the aid of the teacher the learners can also become co-involved in the design and writing of these assessment criteria, which will be focused on the attainment of the formulated learning outcomes. Where learners are actively involved in their own assessment, learning is normally more effective. It also improves motivation and leads to higher academic performance.39

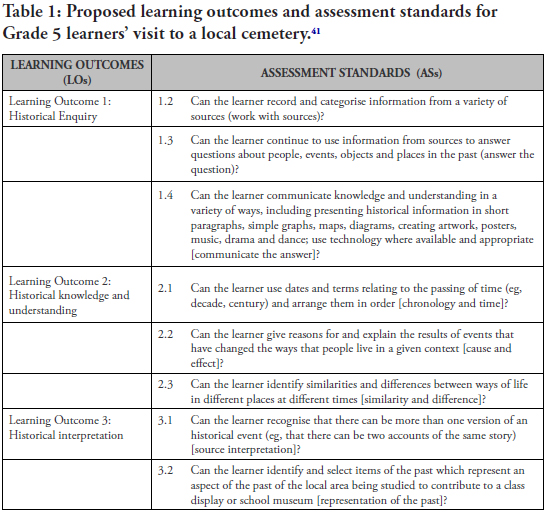

In the following example (See Table 1) the learning outcomes and assessment standards for Grade 5 learners are stated as contained in the NCS. Grade 5 constitutes part of the Intermediate Phase (Grades 4-6) where teachers are encouraged to, amongst others, place more emphasis on "the history of a local area" so that the connection or relation between "heritage and identity" can be clearly established.40

A possible methodology

As mentioned earlier, some of the reasons why teachers are not very keen on undertaking excursions to heritage sites are, amongst others, the amount of time spent on the administrative and logistical planning and preparation thereof as well as the financial implications that it brings about. Concerning the aforementioned, the paragraphs above indicate that in reality a visit to a cemetery does not require that much input. (See: "The planning and preparation for a visit to a local cemetery".)

A lack of financial resources should also not stand in the way of a visit to a cemetery. Instead of the learners reporting to school at the beginning of the school day, it can be arranged that all the learners meet at the particular cemetery. This arrangement will ensure sufficient time for the teacher and the learners to do the planned activities. Where practically possible and if time permits, an additional cemetery close by can also be visit; one that is older or which represents another culture group. At the end of the school day the learners can then be dismissed from the site instead of the school premises. When the site visit is arranged in this manner, it will limit financial expenses to the minimum and will also be the least disruptive where the school time table is concerned.

With the administrative and logistical arrangements that will not require too much time and effort, a next step for the teacher is to develop a particular method that will make it possible for the learners to research the information on the local cemetery. A method that could be followed is to design a cemetery worksheet. Both the teacher and the learners can be instrumental in the development and composition of this worksheet. Groups consisting of four learners each can then complete the worksheet after each group has been allocated a particular section of the cemetery. To make sure that time is not unnecessarily wasted during the visit, it is essential that the teacher, and where possible also the other staff that will act as facilitators, visit the particular cemetery before the time to demarcate each group's area. Before the excursion takes place, it is also important that the teacher should discuss the worksheet with the learners and facilitators so that everyone knows exactly what is expected of them during each activity.

When the worksheet for a visit to a cemetery is being designed, it should make provision for:

• Activities that are aimed at the attainment of the formulated learning outcomes;

• a systematic and clear layout with a high degree of technical care;

• a variety of activities that takes into consideration the level of development of the particular learners;

• open and close ended questions that will allow the learners to develop different historical skills;

• activities that make provision for the integration of the different subject disciplines;

• the assessment instrument together with the assessment criteria that are going to be applied;

• an opportunity for reflection for the learners at the end of the visit; and

• follow-up activities.42

The following is an example of what a worksheet for Grade 5 learners can look like for a visit to a cemetery.43 It can be adapted by the teacher, depending on the age and level of development of the learners.

The follow-up period

After the visit to a cemetery it is essential to do follow-up work. It contributes to a reinforcement and consolidation of the skills, ideas and information that were acquired during the visit.44 It is possible to divide or classify the follow-up period in three stages, namely the immediate, intermediate and long-term stage. Immediate follow up can be done while the learners are still at the cemetery or even the next day in the classroom. During this stage the learners should be encouraged to discuss with their classmates what they have experienced and seek answers to the problems they might have encountered. The teacher must also show interest in the learners' reactions by summarising the main findings of the different groups and at the same time also rectifying any misunderstandings that might exist.45 In this stage it is also important that the assessment criteria, which were designed by the teacher and learners prior to the excursion, now, be applied by the learners to assess each other in order to establish whether the formulated learning outcomes were attained. When groups assess each other, it has, amongst others, the advantage that it develops the learner's ability to function in a group where emphasis is placed on interpersonal and communicative skills. Reflective learning also occurs during group assessment and learners also adopt a more critical disposition towards their own learning. They accept more responsibility for their own learning by looking for ways to improve the learning efforts. This all contributes to them becoming lifelong learners.46

For the intermediate stage, the follow-up process can entail the composition of a class record of what the various groups have discovered. An opportunity can also be created for creative self-expression were learners can put together a general display of graphs, photographs and sketches accompanied by written texts, which will contribute to a total picture of the heritage visit. As a further motivation to produce high quality work, these efforts can be exhibited at a place in the school for all the learners to see.

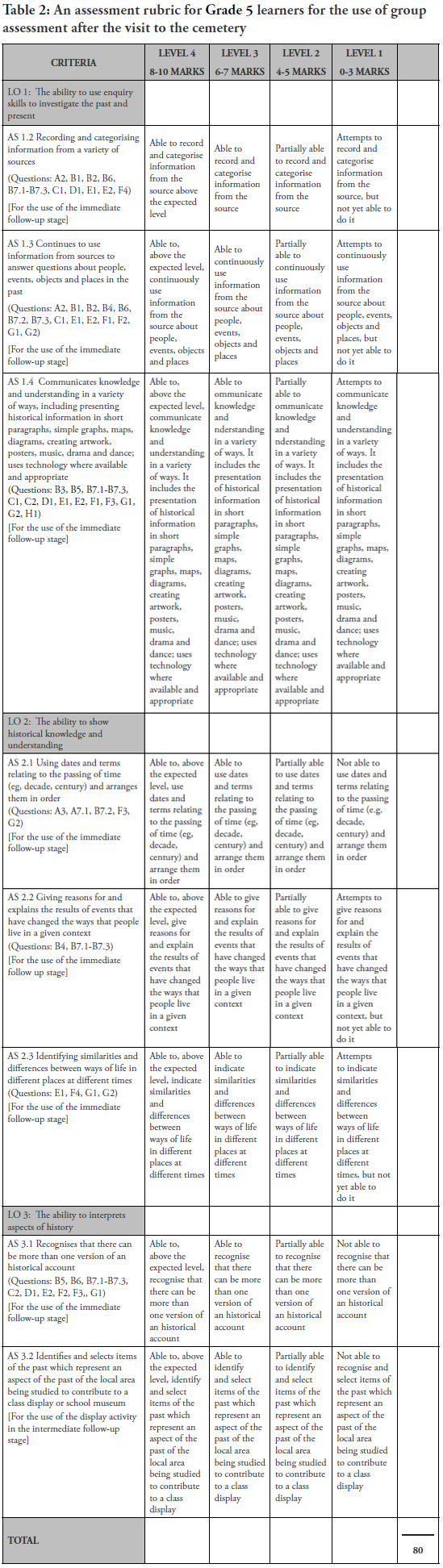

In the long-term stage the follow-up work can consist of further follow-up research projects, which will arise from the information already gathered and through which new knowledge will be generated.47 Table 2 is an example of a scoring rubric that the groups can use as an assessment instrument to assess each other during the immediate and intermediate follow-up stages.

Conclusion

The value of a visit to a heritage site like a local cemetery cannot be overstated. A well planned trip with proper instruction prior to the occurrence, followed by a methodology where learners are actively busy "to do" heritage, offer them insights and perspectives, which is not possible in the traditional setting of a classroom. By doing heritage, learners work like the historian because information is gathered, sifted or screened, arranged and interpreted.

When locally rooted, "heritage grows from the bottom up".48 It helps learners to remake their past by broadening and deepening their understanding not only of their own heritage, but also of that of other distinctive ethnical cultures. Research evidence proves that people first identify almost solely with their own heritage before identifying on a much larger scale with a broader multi heritage.49

By mutual understanding and by giving recognition to other culture groups' contributions, heritage becomes more inclusive and socially responsible. It helps to construct a shared past that in the end will contribute to a sense of pride that will eventually cherish the ideal of a common South African heritage and identity. Only then heritage will no longer be abused as a vehicle to strengthen the position of a dominant community or ruling party.50

1 T Copeland, "Heritage education and citizenship" (Paper, The Nostra Forum, the Hague, 1 October 2004),p.70 (available at: http://www.europanostra.org/UPLOADS/FILS/forum_heritage_education_proceedings.pdf, as accessed on 10 Jun. 2010); [ Links ] BA Vansledright, Historical study, the heritage curriculum, and educational research, Issues in Education, 4(2),1998pp.229-235. [ Links ]

2 MLS Sørensen & J Carman, "Introduction. Making the means transparent: Reasons and reflections", MLS Sørensen & J Carman (eds.), Heritage Studies: Methods and Approaches (London, Routledge, 2009),pp.3-10; [ Links ] ME Garden, "The heritage escape: Looking at heritage sites", MLS Sørensen & J Carman (eds.), Heritage Studies: Methods and Approaches,pp.270-292. [ Links ]

3 Compare BJJ Lombard, "Outcomes-Based Education in South Africa: A brief overview", L Meyer, K Lombard, P Warnich & C Wolhuter, Outcomes-Based assessment for South African teachers (Pretoria, Van Schaik Publishers, 2010),pp.1-29. [ Links ]

4 T Copeland, "Heritage and education: A European perspective" (Keynote speech at the Nostra Forum, the Hague, 1 October 2004), p.68 (available at: ttp://www.europanostra.org/UPLOADS/FILS/forum_heritage_education_proceedings.pdf, as accessed on 10 June 2010). [ Links ]

5 Compare RJ Pérez, JMC López, & DMF Listán, Heritage education: Exploring the conceptions of teachers and administrators from the perspective of experimental and social science teaching, Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(6), August 2010,pp.1319-1320; [ Links ] MLS Sørensen, "Between the lines and in the margins: Interviewing people about attitudes to heritage and identity", MLS Sørensen & J Carman (eds.), Heritage Studies: Methods and Approaches,pp.164-177. [ Links ]

6 J Strong, Enhanced Strong's Lexicon (Oak Harbour, WA, Logos Research Systems, Inc., 1995); [ Links ] S Zodhiates (ed.), The complete World Study Dictionary: New Testament (Chattanooga, TN: AMG Publishers, 1992),p.867; [ Links ] Renn, SD (ed.), Expository Dictionary of Bible words based on the Hebrew and Greek Texts: World studies for key English Bible words. (Massachusetts, Hendrickson Publishers, 2005),p.517. [ Links ]

7 U Sommer, "Methods used to investigate the use of the past in the formation of regional identities", MLS Sørensen & J Carman (eds.), Heritage Studies: Methods and Approaches,pp.103-120. [ Links ]

8 HA Soderland, "The history of heritage: A method in analysing legislative historiography", MLS Sørensen & J Carman (eds.), Heritage Studies: Methods and Approaches,pp.55-84. [ Links ]

9 RS Peckham, "The politics of heritage and public culture", RS Peckham (ed.), Rethinking heritage: Cultures and politics in Europe (London, IB Tauris, 2003),pp.1-13. [ Links ]

10 S Macdonald, Undesirable heritage: Fascist material culture and historical consciousness in Nuremberg, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 12(1),January 2006,p.11. [ Links ]

11 RS Peckham, "The politics of heritage and public culture", RS Peckham (ed.), Rethinking heritage: Cultures and politics in Europe,pp.1-13. [ Links ]

12 HY Park, Heritage tourism: Emotional journeys into nationhood, Annals of Tourism Research, 37(1),January 2010,p.117. [ Links ]

13 MLS Sørensen & J Carman, "Introduction. Making the means transparent: Reasons and reflections", MLS Sørensen & J Carman (eds.), Heritage Studies: Methods and Approaches, pp.3-10. [ Links ]

14 JD Jansen, Curriculum reform in South Africa: A critical analysis of Outcomes-Based Education [1], Cambridge Journal of Education, 28(3),1998,pp.321-332. [ Links ]

15 Especially the Standard 2 (Grade 4) syllabus made amply provision for the teaching of local history, see DJJ Coetzee, Plaaslike geskiedenis: Wat is dit en waarom is die aanbieding daarvan in skole wenslik?, Die Unie, 84(2),Augustus 1987,p.112. [ Links ]

16 Compare J Mathews, K Moodley, W Rheeder & M Wilkinson, Discovery History: A pupil-centred approach to History method (Cape Town, Maskew Millar Longman, 1992),p.88; [ Links ] WL Rheeder, The cemetery as a resource in the study of local history, Educamus, 37(8),October 1991,p.30. [ Links ]

17 ES van Eeden, Didactical guidelines for teaching history in a changing South Africa (Potchefstroom, Keurkopie, 1999),p.111. [ Links ]

18 A Jackson, Local and regional history as heritage: The heritage process and conceptualizing the purpose and practice of local historians." International Journal of Heritage Studies, 14(4),July 2008,pp.362-379. [ Links ]

19 C Jooste, Plaaslike geskiedenis as 'n genre vir sekondêre Geskiedenisonderrig met verwysing na spesifieke bronnemateriaal beskikbaar in Laudium, Yesterday and Today, May 2007,pp.206-208 [ Links ]

20 DJJ Coetzee, Plaaslike geskiedenis: Wat is dit en waarom is die aanbieding daarvan in skole wenslik?, Die Unie, 84(2),Augustus 1987,p.34. [ Links ]

21 Van Wijk, L Developments in heritage education in Europe: EUROCLIO'S enquiries compared, International Journal of Historical Teaching, Learning and Reform, 5(2),July 2005,p. 1. [ Links ]

22 Department of Education (DoE), Revised National Curriculum Statement Grades R-9 (Schools), policy, Social Sciences (Pretoria, Department of Education, 2002),pp.10-11. [ Links ]

23 DoE, Revised National Curriculum Statement Grades R-9 (Schools), policy, Social Sciences,pp.37-40. [ Links ]

24 DoE, Revised National Curriculum Statement Grades R-9 (Schools), policy, Social Sciences,pp.59-62; [ Links ] Also compare J Deacon, Heritage and African history, S Jeppie (ed.), Toward new histories for South Africa. On the place of the past in our present (Landsdowne, Juta Gariep, 2004),pp.121-125. [ Links ]

25 DoE, National Curriculum Statement Grades 10-12 (general), History (Pretoria, Department of Education, 2003),pp.14,22-23; [ Links ] DoE, National Curriculum Statement Grades 10-12 (general), Subject assessment guidelines, History (Pretoria, Department of Education, 2007),p.26. [ Links ]

26 The South African Society for History Teaching (SASHT), "Introductory statement for call for conference papers on the theme Heritage in the history curriculum: The how to of yours, mine and ours in a still divided community environment." Held on 24 and 25 September at the Golden Gate Highlands National Park in the Free State Province, 2010 (available at http://www.sashtw.org.za/, as accessed on 20 Sep. 2010). [ Links ]

27 MLS Sørensen & J Carman, "Introduction. Making the means transparent: Reasons and reflections", MLS Sørensen & J Carman (eds.), Heritage Studies: Methods and Approaches (London, Routledge, 2009),pp.3-10. [ Links ]

28 PG Warnich, "Uitkomsgebaseerde assessering van Geskiedenis in Graad 10", (Potchefstroom NWU, PhD., 2008),pp.440,445. [ Links ]

29 WB Stephens, Teaching local history (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1977),p.153; [ Links ] RL Stevens, Homespun: Teaching local history in grades 6-12 (Portsmouth, Heinemann),pp.12-15. [ Links ]

30 J Mathews, K Moodley, W Rheeder & M Wilkinson, Discovery History: A pupil-centred approach to History method (Cape Town, Maskew Millar Longman, 1992),pp.88-91; [ Links ] H. Ludlow, Using local history to apprentice undergraduate students into the practices of the historian, South African Historical Journal, 57,2007,p.208. [ Links ]

31 H Ludlow, Using local history to apprentice undergraduate students into the practices of the historian, South African Historical Journal, 57,2007,p.202. [ Links ]

32 Compare WB Stephens, Teaching local history (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1977),p.139. [ Links ]

33 Compare WB Stephens, Teaching local history, p. 138. [ Links ]

34 ES van Eeden, Didactical guidelines for teaching history in a changing South Africa,p.184. [ Links ]

35 DoE, Revised National Curriculum Statement Grades R-9 (Schools), Teacher's guide for development of learning programmes Social Sciences (Pretoria, Department of Education, 2003),pp.32-33; [ Links ] J Mathews, K Moodley, W Rheeder & M Wilkinson, Discovery History: A pupil-centred approach to History method (Cape Town, Maskew Millar Longman, 1992),pp.92-93. [ Links ]

36 DoE, National Curriculum Statement Grades R-9 (Schools), Teacher's guide for development of learning programmes, Social Sciences,p.33. [ Links ]

37 WB Stephens, Teaching local history,pp.34-35. [ Links ]

38 Assessment agents refer to those who are responsible for carrying out the assessment. Assessment agents who stand in the midst of the learning and teaching chain of events are the learner, the peer/friend, the group and the parents. See PG Warnich, "Uitkomsgebaseerde assessering van Geskiedenis in Graad 10", (Potchefstroom NWU, PhD, 2008),pp.136-145. [ Links ]

39 PG Warnich, "The planning of Outcomes-Based Assessment in South African schools", L Meyer, K Lombard, P Warnich & C Wolhuter, Outcomes-Bases assessment for South African teachers,p.105. [ Links ]

40 DoE, Revised National Curriculum Statement Grades R-9 (Schools), policy, Social Sciences,pp.38-39. [ Links ]

41 DoE, Revised National Curriculum Statement Grades R-9 (Schools), policy, Social Sciences,pp.43,45,47. [ Links ]

42 Compare DoE, Revised National Curriculum Statement Grades R-9 (Schools), Teacher's guide for development of learning programmes, Social Sciences,p.33; [ Links ] WB Stephens, Teaching local history,p.142. [ Links ]

43 RL Stevens , Homespun: Teaching local history in grades 6-12 (Portsmouth, Heinemann, 2001),pp.18-21; [ Links ] P Hughes, Local History (Warwickshire, Scholastic Ltd, 1997),pp.122-123; [ Links ] WL Rheeder, The cemetery as a resource in the study of local history, Educamus, 37(8),October 1991,pp.31-32; [ Links ] DJJ Coetzee, Plaaslike geskiedenis: Wat is dit en waarom is die aanbieding daarvan in skole wenslik?, Die Unie, 84(2),Augustus 1987,p. 113; [ Links ] FD Metcalf & MT Downey, Using local history in the classroom (Nashville, The American Association for state and local history, 1982),pp.114-117,255-262; [ Links ] J van Biljon (ed.), Local History, N.E.D. Bulletin, 39,1984,pp.23-27. [ Links ]

44 DoE, Revised National Curriculum Statement Grades R-9 (Schools), Teacher's guide for development of learning programmes, Social Sciences,p.33. [ Links ]

45 J Mathews, K Moodley, W Rheeder & M Wilkinson, Discovery History: A pupil-centred approach to History method (Cape Town, Maskew Millar Longman, 1992),pp.93-95; [ Links ] WB Stephens, Teaching local history,pp.155-157. [ Links ]

46 GP van Rheede van Oudtshoorn & D Hay, Group work in higher education: A mismanaged evil or a potential good?, South African Journal of Higher Education, 18(2),2004,p.131; [ Links ] S Chappuis & RJ Stiggins, Classroom assessment for learning, Educational Leadership, 60(1),September 2002,pp.40-43; [ Links ] W Cheng & M Warren, Making a difference: Using peers to assess individual student's contributions to a group project, Teaching in Higher Education, 5(2),April 2000,p.252. [ Links ]

47 J Mathews, K Moodley, W Rheeder & M Wilkinson, Discovery History: A pupil-centred approach to History method,p.94; [ Links ] WB Stephens, Teaching local history (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1977),pp.155-157. [ Links ]

48 J Deacon, "Heritage and African history", S Jeppie (ed.), Toward new histories for South Africa. On the place of the past in our present (Landsdowne, Juta Gariep, 2004),p.120. [ Links ]

49 T Copeland, "Heritage and education: A European perspective" (Keynote speech at the Nostra Forum, the Hague, 1 October 2004),p.21 (available at http://www.europanostra.org/UPLOADS/FILS/forum_heritage_education_proceedings.pdf, as accessed on 10 June 2010). [ Links ]

50 J Deacon, "Heritage and African history", S Jeppie (ed.), Toward new histories for South Africa. On the place of the past in our present,p.119. [ Links ]