Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Yesterday and Today

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9003

versão impressa ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T no.5 Vanderbijlpark Jan. 2010

ARTICLES

The value of open distance learning (ODL) in assisting History teachers with heritage investigation

Henriëtte J Lubbe

Ms. University of South Africa. Pretoria. lubbehj@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article highlights some of the challenges facing history teachers in designing and assessing heritage investigation projects in the Further Education and Training (FET) band and the need for teachers to be proactive in terms of their professional development. It also explores ways in which open distance learning (ODL) can address these challenges by providing guidance, encouragement, practical skills training and resource material, especially to those teachers who cannot take their learners to a museum or heritage site for material or logistical reasons. The article is anchored in a qualitative research methodology and reports on student feedback on the Short Course in School History Enrichment offered by the Department of History at the University of South Africa (Unisa) as well as ongoing inquiry into teacher experience of teaching heritage investigation. It also shares the author's personal reflections based on informal communication with course candidates and other teachers over a period of more than ten years. The article argues that ODL can play a significant role in history skills development at secondary school level in general and in enhancing the self-confidence and skills of teachers having to teach heritage investigation in particular. It also emphasises the value of informal partnerships between the ODL institution and role players in the heritage field and makes a plea for closer cooperation between academic historians, history teachers, the Department of Basic Education and the heritage sector.

Keywords: Heritage; History; Open distance learning; ODL; Unisa History Department; Short Course in School History Enrichment; Teacher training, FET; Museums; Heritage sites; Electronic resources.

Introduction

Teaching LO 4 (Heritage) was a stumbling block in my teaching of history. Registering for SCHE0161 served as an eye-opener. I am now able to conduct interviews, organise research portfolios, formulate questions, present data from interviews, identify unsung heroes and heritage sites in our locality which I think are undeclared. My Gr 12 results have also improved.2

This response from a histor y teacher who completed the Short Course in School History Enrichment offered by the History Department at the University of South Africa (Unisa) in 2010, succinctly captures the candidate's initial anxiety about not knowing quite how to handle heritage in the history classroom, his growing confidence and professional competence as a result of enrolling for skills development via open distance learning (ODL),3 and his ultimate triumph in achieving greatly enhanced learner performance. Far from being an isolated example, the views expressed in the quotation have been confirmed by qualitative research conducted in the Unisa History Department between 2009 and 2011, the findings of which are discussed in this article. The article highlights the main challenges facing history teachers having to teach heritage investigation in the Further Education and Training (FET) band and explores the value of ODL in empowering them to design and assess heritage projects more effectively and creatively. It shares some of the ODL techniques which have been employed by the Unisa History Department to achieve this objective and offers suggestions for closer cooperation between academic historians, education officials and heritage professionals in order to provide teachers with clearer guidance and additional resource material, especially in cases where a class visit to a museum or other heritage site is impossible. Finally, it emphasises the role of the individual teacher who has to take initiative and responsibility for his or her own professional development in order to remain motivated and provide learners with a memorable experience.

Challenges in teaching heritage investigation

Since the introduction of a compulsory heritage assignment in all three grades of the FET band (Grades 10 to 12) in 2008, heritage investigation has inspired some history teachers to teach the theme with creativity and passion4 but has generated much anxiety among others. With no specific training in the heritage field, a very full syllabus to be covered in limited time, inadequate guidance from subject specialists (facilitators), and little or no training by the Department of Education (DoE)5, many history teachers not only lack the time but also the confidence and skills to implement heritage investigation effectively in the classroom. Non-prescriptive DoE guidelines for heritage projects leave scope for teachers to be creative but also create uncertainty about the precise requirements in terms of format, length, assessment and ideological approach.6 Moreover, many teachers are not qualified assessors and therefore struggle with the design and application of assessment tools such as rubrics. This compromises effective assessment of heritage investigation projects.7 Too often, learners simply reproduce information supplied by their teacher or submit superficially researched assignments just so that a mark can be recorded. Worse still - in order to ensure good year marks, some teachers award inflated marks for assignments that have been plagiarised from the Internet while little or no real learning has taken place.8 Teachers who received their training during the era of apartheid and Bantu education have also been conditioned to think in terms of differences rather than commonalities between people. Believing that they are affirming previously neglected historical perspectives and promoting local history and heritage, they often reinforce divisions without guiding learners towards critical engagement with broader heritage issues and a sound understanding of the complexities of a common South African past.9 Here guidance from academic historians may provide clearer direction. However, many professional historians regard history and heritage as two different academic pursuits and are wary of heritage's association with a political agenda and the "commodification" of history which tends to oversimplify complex historical processes and debates in order to attract the tourist industry.10

Lack of resources such as computers, tape recorders and cameras, lack of access to the Internet, the distance from facilities such as museums, monuments, libraries and archives, as well as the financial status of parents who often cannot contribute financially towards a class visit to a heritage site, make the task of the history teacher having to teach heritage investigation even more challenging.11 The consequent heavy reliance on oral investigation has problems of its own, one of which is reluctance on the part of some community members to participate in heritage investigation projects.12

To complicate the matter even further, the DoE's draft Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) for history has recently confined heritage investigation to Grade 10, offering no clear guidelines with regard to content and methodology other than insisting on a research component aimed at teaching research skills.13 Although research skills are certainly lacking in many schools,14 and it therefore makes sense to include a compulsory research-based heritage investigation assignment in Grade 10 where the syllabus is not so full and teachers have more time to teach heritage thoroughly, one cannot help but fear that the CAPS document, if implemented unchanged, will eventually cause heritage to be completely sidelined in Grades 11 and 12.

It is against this backdrop that the Department of History at the University of South Africa (Unisa) decided to step in and assist history teachers via open distance learning (ODL) in teaching history and heritage more effectively and creatively.

The value of ODL in teacher training

The literature on open distance learning (ODL) indicates that universities across the world are increasingly offering teacher training programmes via ODL15 in order to address the shortage of qualified teachers and improve the qualifications of under-qualified educators.16 It also suggests that ODL can be effective in offering work-integrated learning17 and practical teacher training provided that students receive high quality tutorial materials and student support. ODL has proved to be effective in providing students with relevant knowledge, improving their professional competence, and enhancing emotional competencies such as taking responsibility for personal and professional development, emotional maturity, self-motivation, self-discipline, dedication and perseverance.18

Qualitative research conducted in the Unisa History Department during 2009 indicated that the Department's Short Course in School History Enrichment (SCHE016)19 - a non-formal short learning programme which functions as a "community engagement"20 project in terms of university policy and is aimed at supporting and empowering history and social science teachers through practical skills training21 - had been very effective over a period of ten years.22 Respondents23 found the tutorial material of the three syllabus-related course options24 accessible, learner-centred and of high quality.25 They also reported having developed a much more interactive, learner-centred approach to teaching and an improved ability to stimulate classroom debate, instil values and shape attitudes as a result of the course.26 Not only had they gained much needed resource material, but had also acquired fresh ideas to conduct group work, handle oral research and teach source-based and extended writing. They had also learnt to think more creatively, analyse and interpret historical sources more effectively, and implement a wider variety of assessment strategies.27 On a psychological level, both teachers and learners felt more empowered, more motivated and more self-confident as a result of the course,28 all of which translated into significantly enhanced pass rates.29 In view of the success and networking function of the Short Course, it presented itself as an ideal avenue to address emerging needs among history teachers.

Although the respondents (n=9030 with a response rate of 41,1%) had initially not been questioned on how they experienced teaching heritage investigation, some did make use of open-ended questions in the 2009 questionnaire to share the challenges they were facing in designing and assessing heritage projects.31

A similar need for assistance became apparent during informal conversations with Short Course candidates, tutors and education officials. This encouraged the Short Course coordinator to send out another questionnaire towards the end of 2010 to all the candidates (n=24) who had completed the Short Course during that year. In six semi-structured questions respondents were asked whether they regarded heritage investigation as important and why; how they went about teaching heritage in their classroom; how their learners responded to the heritage projects they were given; what obstacles they encountered in teaching heritage investigation; what kind of support they needed to teach heritage investigation more effectively, and if and how the Short Course had assisted them in teaching heritage efficiently.32 Unfortunately only two teachers responded to this questionnaire (response rate of 8,3%) which proved to be ill-timed as it was sent out at the end of the 2010 academic year to candidates who had already qualified.33 The same questionnaire was despatched again to these teachers earlier this year as well as to the 26 new registrations for 2011. Responses are expected only later this year and will be reported on in a future article.34

Student feedback that has been received so far indicates (but cannot be generalised as a result of sample size and response rate) that teachers regard heritage investigation as important because it teaches learners to discover their roots,35 promotes indigenous knowledge systems and helps South Africans to understand and respect different identities, cultures, traditions, languages and belief systems. Most favoured methods used to teach heritage investigation include group work, class debates around indigenous knowledge systems, the investigation of undeclared heritage sites close to where the learners live,36 and oral interviewing of community elders. Learner responses to these heritage investigation activities are reported to be very positive including a high level of participation, diligent transcription of oral interviews, careful organisation of research files complete with key question, planning, list of interviewing questions and transcribed answers, historical contextualisation and self-reflection.37 In terms of additional support required, the respondents need the DoE to consider history as a scarce skills subject, and to empower history teachers through resuscitation programmes, history workshops and in-service training. They would also like to be informed of historical associations and organisations which they can join.38 Finally, they request heritage-related didactical guidance on DVD,39 and suggest that more history teachers should receive assistance with heritage investigation via ODL like they did.40

But how can something as practical as heritage investigation be taught via distance?

Bridging distance in ODL

Open distance learning (ODL) - which is characterised by student-centred, flexible, integrated and technology enhanced learning41 - has the ability to narrow the physical and transactional distance between the student and the ODL institution through the use of multimedia42 such as audio cassette,43 radio,44 television,45 CD Rom, DVD,46 SMS technology, video conferencing, satellite broadcasts and the Internet. Studying through an ODL institution such as Unisa, for example, provides flexible part-time study opportunities to students in both the urban centres and rural areas of South Africa and abroad. Students can choose between receiving printed tutorial material and submitting assignments by mail, or downloading study material and submitting assignments electronically. Those who have access to the Internet can also share ideas and emotions with fellow students and lecturers by participating in online discussions via Unisa's learning management system, myUnisa.47

As a result of the relatively small size48 of the Short Course, its scattered student base, lack of human and financial resources in the Unisa History Department, and many students' lack of easy access to Internet facilities, sophisticated ODL techniques such as video conferencing, satellite and television broadcasts as well as Web2 applications and MXit49 are not yet viable in this short learning programme. For many of the same reasons face-to-face contact in the form of regular teacher training workshops, although ideal, is also not possible.50 The Short Course therefore relies mainly on a print-based mode of tuition which does not disadvantage any of its students.

What makes the course unique though is that academics in the History Department work together with practising teachers who are contracted to assist with course development, continuous updating of tutorial materials in order to keep up with syllabus and educational policy changes,51 and the assessment of the practical projects. This fruitful partnership ensures that course candidates receive appropriate didactical guidance, syllabus-related, National Curriculum Statement (NCS)-directed52 assignments for practical application in the classroom, and constructive feedback which assists candidates in expanding their knowledge, improving their teaching skills, building their confidence, enhancing their creativity and building the academic capacity of their learners - all of this while working full time and studying part-time towards a professional qualification.53

Although most of the study material and assessment tasks are print-based,54 the tone of written communication is always warm and personal in order to break the isolation which puts ODL students at a distinct disadvantage.55 Short Course candidates also have 24-hour access to the course coordinator via e-mail, SMS and cell phone every day of the week including weekends and public holidays. This has enabled the course coordinator to build close relationships with many history teachers, provide them with immediate didactical support and encouragement, and keep them focused and motivated.

Empowering teachers via ODL to teach heritage investigation

There are several ways in which the Unisa History Department strives to assist history teachers with heritage investigation:

Written assignments

In at least one assignment in Option A (History, Grades 11 and 12) and Option B (History, Grade 10) of the Short Course candidates are invited to develop a heritage investigation task appropriate for the grade they teach and based on a visit to any museum or heritage site of their choice. Even candidates enrolled for Option C (Social Sciences, Grades 8 and 9), are encouraged to structure a group work activity around any heritage theme.56 Candidates need to include all the relevant learning outcomes (LO's) and assessment standards (AS's), key question, instruction sheet where applicable, assessment criteria, marking rubric, historical sources they would use, questions they have set together with the mark allocation, and a well prepared memorandum. For additional credit, they are encouraged to include an example of a heritage project submitted by one of their learners and marked by the teacher as well as a self-assessment of how well the particular activity worked in practice. This can then assist the teacher to improve the activity for reuse the following year. Once assessed, each assignment is mailed back to the student together with comprehensive commentary by a tutor (assessor) with extensive teaching experience. The assessor's report offers constructive commentary on all aspects of the assignment, guides the student towards critical engagement with historical sources and provides guidance with regard to historical debates around heritage issues. Where necessary, the candidate also receives additional source material and a marking rubric which could be used to assess learners' heritage projects.57 Candidates who do not pass an assignment are allowed to rework and resubmit their work until they are successful. In this way every candidate benefits from formative assessment and a pass rate of more than 80% is achieved.58

In general, Short Course tutors encourage teachers to take their learners to a museum or heritage site if possible and to use heritage themes in a wide range of classroom activities including group work, oral investigation, research assignments, source-based and extended writing as well as heritage investigation projects. They also suggest to teachers that they focus on one heritage theme throughout the FET phase. The Grade 10 project would consist of a basic introduction to the concept of "heritage" and create an awareness of various types of heritage sites - archaeological, paleontological, cultural, historical and environmental. In Grades 11 and 12 the theme of choice could be explored in greater depth and ultimately linked to "nation building" which is a central theme in the FET history syllabi.59

Electronic resources

In addition to printed tutorial materials, various electronic products - in particular CD and DVD which have proved to be the most appropriate technology for the course60 - have been developed to ease the workload of teachers and provide them with creative ideas and additional didactical guidance and assistance. These electronic resources include the "First Aid for FET" and "Short Cuts to Teaching Social Science" CD's, the "Work Smarter Not Harder" DVD (which includes worksheets, resource material and a marking rubric for heritage projects that can be downloaded from an accompanying CD) and a new DVD on teaching heritage investigation which is currently in progress.61

In order to empower as many teachers as possible, these electronic resources have not been limited to Short Course candidates only but have been made available for sale to all history and social science teachers across South Africa.62

Group work on DVD

In one insert on the "Work Smarter, Not Harder" DVD, we show teachers visually how group work could be utilised in the classroom in order to engage learners in heritage investigation. Using the theme of Sarah Baartman as an example, the insert on the DVD illustrates how the teacher interacts with her learners while working in small groups; how she encourages the learners to think critically about issues relating to heritage, and how she guides the learners to complete a worksheet. The insert also shows how peer assessment is integrated into the assessment of learner performance during the activity.63

Video footage of a museum visit

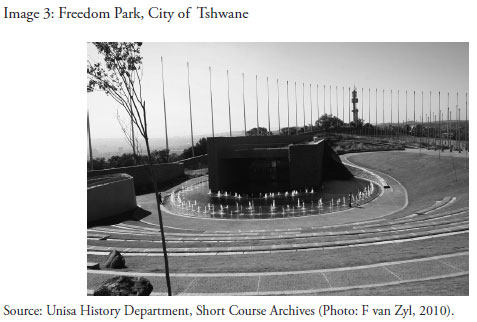

In another insert on the same DVD, the teacher who cannot bring his/her learners to Freedom Park in Tshwane/Pretoria, receives video footage of a teacher and her learners on a guided tour of Freedom Park.

The visual material covers the most significant heritage resources available at Freedom Park and captures portions of the tour guide's explanations and the teacher's interaction with her learners. Again, a downloadable worksheet provides a variety of resource material on Freedom Park and possible questions as a basis for a heritage investigation assignment. The worksheet also guides teachers towards building in progression from one grade to the next by setting higher level questions based on comparisons between Freedom Park and the neighbouring Voortrekker Monument.64

Digital photographs

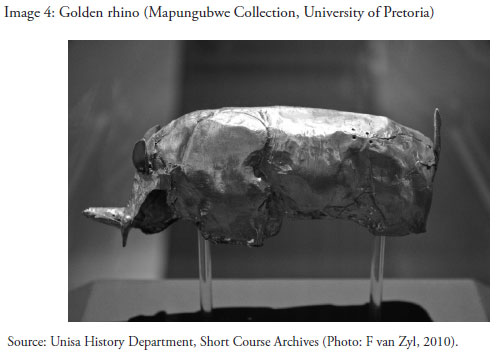

Another way of "bringing the heritage site to the teacher" should he/she not be able to take the learners on a heritage excursion, is to make photographs of museum or other heritage material available on CD or DVD. These photographs can then be shown in class and/or printed out as sources for a heritage investigation assignment. With the kind cooperation of the Mapungubwe Museum at the University of Pretoria, for example, a fascinating variety of artefacts from the Mapungubwe Collection have been photographed for inclusion on the new "Tips for Teaching Heritage" DVD.

The museum has also donated informative brochures which can be used as source material by teachers and learners who may never be able to visit the museum. These brochures will be made available to Short Course students registered for the 2011 academic year.

The brochures and photographs mentioned above constitute the core resource material for a ready-made Grade 10 heritage investigation assignment which can be downloaded from an accompanying CD. Teachers are also alerted to other reading material65 and Internet sources66 on Mapungubwe in order to convey the importance of consulting a wide variety of historical evidence. The example assignment comes complete with a key question, LO's and AS's, a wide variety of questions with mark allocation, marking rubric and memorandum, as well as sections on data handling and creating promotional material for the tourist industry. Moreover, the teacher using the example receives advice on how to tap into foundational knowledge acquired in Grade 6 and adapt the material for a Grade 11 or Grade 12 research assignment. This can be achieved by introducing comparisons with heritage sites such as Great Zimbabwe and Thulamela and by formulating more advanced questions that test higher level intellectual abilities.67

Filming museum resources

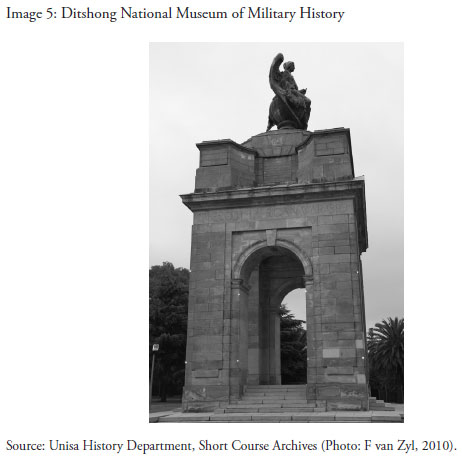

Making our own "movies" is yet another way in which the Short Course team offers teachers resources and fresh ideas for creative heritage investigation. The first of its kind deals with the impact of war on society and technological development and was shot at the Ditshong National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg towards the end of 2010. The story begins with visuals of the war memorial outside the main entrance to the museum with comment on how various communities commemorate the same historical event differently and how interpretations may change over time.

It then moves inside to a bust of General Smuts which can be used to make the viewer think critically about the role of powerful military and political leaders in world events. The film then explores the contribution of "ordinary" South Africans such as Job Maseko and Lucas Majozi and reflects on the lack of proper reward for black South African soldiers after World War II. It subsequently shows how their intense bitterness became part of the anti-apartheid struggle as reflected in the Mkhonto we Sizwe collection at the museum.

War also leads to technological development, and so the film depicts selected examples of old aeroplanes, rifles, armoured vehicles and military uniforms in order to illustrate technological development through time. In order to provide the teacher with sources which learners can study and re-study in class or at home after having watched the DVD, digital photographs of museum resources depicted in the film are also provided for download from the accompanying CD. In addition, an example assignment is provided in order to assist the teacher in designing appropriate heritage investigation assignments for different grades.68

Music, poetry and art

Apart from the more conventional written assignments discussed above, Short Course candidates are encouraged to construct heritage investigation projects around resistance music, poetry or art. They need to provide at least two examples of the selected art form and include an English translation where applicable - apart from, of course, meeting all the basic requirements for setting a heritage investigation assignment. Among the excellent contributions that were submitted during 2010 was a very original project structured around published69 protest poetry which aptly captures emotions during the 1976 student uprisings.70 Another student submitted liberation songs from the anti-apartheid struggle on CD together with his written assignment and used two of the songs to design an assignment on working with sources. This student later reshaped this assignment into a Grade 11 heritage investigation activity for additional credit.71 There is ample scope in this field to be creative and websites such as those of South African History Online and the Archival Platforms72 alert teachers to relevant sources and debates around, for example, the banning of struggle songs.73

For a more challenging approach to exploring heritage via resistance music, teachers are encouraged to introduce a comparative element by selecting protest music from across the racial and cultural divide. For example, Blondie Makhene's "Siyaya"74 could be combined with some of the late Lucky Dube's reggae lyrics75 and JPre's [John Pretorius] "Sekunjalo Ke Nako" ("Now is the Time"). JPre's song was first performed on the Grand Parade in Cape Town to celebrate Nelson Mandela's release from prison in 1990. It was subsequently used by the African National Congress at election rallies during the 1994 election campaign in the Western Cape, and was later reworked for performance during the 2010 Soccer World Cup.76 Learners may also find the social and political protest of Afrikaner rock musicians such as Johannes Kerkorrelen die GereformeerdeBlues Band77 during the late 1980s fascinating. Celebrated as liberators by the politically progressive section of the Afrikaner youth, but unable to change the racial attitudes of the majority of young Afrikaners,78 Kerkorrel and his band were rejected by the Afrikaner establishment for their "subversive" criticism of apartheid, military conscription and Afrikaner elitism. The band's music was prohibited from being aired by the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) and its "Voëlvry" ["outlawed"] tour of the country banned from most Afrikaans university campuses. Useful protest songs from their albums79 include "Sit dit af" ["Switch it off"], "Wat 'n vriend het ons in PW" ["What a friend do we have in PW"], "Barend vat ons geld" ["Barend takes our money"],80 and "Hou my vas korporaal"["Hold me tight corporal"],which reminds one of the political storm around the Bok van Blerk song, "De La Rey"81 and Jacob Zuma's Awuleth' Umshini Wami ["Bring me my machine gun"] not too long ago.82 Current rock groups such as the Afrikaans punk rock band Fokofpolisiekar ["F...off police car"]83 could also be included, not only because these names may be more familiar to the learners, but also because the material will enable the teacher to illustrate diverse perceptions of identity, the importance of historical context and historical change through time. If none of the above gets the learners excited, ANC Youth League president Julius Malema's singing in public of "dubul' ibhunu" ["Shoot/kill the farmer"] and the heated media and legal debate this has generated,84 certainly will.

SMS technology

Last but not least - we plan to show teachers on the "Tips for Teaching Heritage" DVD how a new generation of more technologically-minded history learners could be reached via the use of SMS technology. During a group work activity which will be video graphed, learners complete a crossword puzzle on a particular heritage theme and communicate with the teacher for instructions and clues via SMS.85

Conclusion

There can be no doubt that heritage investigation is an exciting tool for the teacher to bring history to life in the classroom. It also creates valuable opportunities for learners to discover their roots, learn about South Africa's complex past, develop healthy values, apply a wide variety of reading, critical thinking, analysis, research and writing skills, and develop a real passion for history. However, many teachers need further training and assistance in order to cope with the challenges they face in teaching heritage investigation. As has been pointed out in this article, open distance learning could be an effective way of conveying the didactical guidance and skills training needed for the design and assessment of heritage investigation projects throughout the FET phase. Short Course candidate Sindiswa Maluleke puts it in a nutshell:

In 2008 one of my learners presented a heritage project and was awarded second place in the Eastern Cape, then proceeded to national level which was quite a good achievement for a school in a rural area to be of the same standard as the schools with resources. In our district, which is Lady Frere, we are placed in the first position for history. In the Eastern Cape we are being recognised for history. I'm very glad that I enriched myself with the Short Course...it really built my capacity as a teacher.86

Ultimately, however, it is about leadership. Not only should academic historians and heritage professionals work together more closely and reach out to history teachers, but the DoE and subject specialists (facilitators) need to provide clearer guidance and support where necessary. History teachers also need to be proactive and take responsibility for their own professional development seeing that the link between good learner performance and inspirational, quality teaching is critical.87 It is therefore up to the teacher to remain inspired, to be creative, to empower him/herself with new knowledge and techniques, and to make every history lesson a memorable experience for both the teacher and the learner.

1 This refers to the Unisa Short Course in School History Enrichment which is offered by the Unisa History Department.

2 Department of History (hereafter DH), Short Course File (hereafter SCF) 5: Q2 - LJ Sekalo, Pretoria. The quotation has been edited slightly.

3 Unlike most international literature which refers to ODL as "open and distance learning", Unisa prefers the term "open distance learning". See JE Mitchell & AI le Roux, "Significant trends in ODL research, as reflected in Progressio", Progressio: South African Journal for Open and Distance Learning Practice, 32(1),2010,p.24,f(2).

4 Examples of excellent heritage projects designed by teachers enrolled for the Unisa Short Course in School History Enrichment include those of E Khosa (Malamulele) on the heritage impact of Mphambo High School; MM Sephuma (Raditshaba) on the Bahananwa and the Leboho chieftaincy; NV Sibawu (Thohoyandou) on the old Grahamstown gaol; V Rietbroek (Roodepoort) on creating a school museum; and LJ Sekalo (Pretoria) on the role of freedom songs as part of South Africa's heritage. See DH: SCF 7, items 1-5.

5 DH: SCF 2: Q29 - JA Peters, Phoenix; Q20 - MB Motsinoni, Ga-Kgapane; Q5 - B Da Silva, Escombe. A Unisa workshop for History teachers from Gauteng West District had to be cancelled as a result of lack of funding for history teacher training in the 2010/2011 DoE budget. See DH: SCF 4: SS Mmotlana (Gauteng Education Department) - H Lubbe (researcher), 1 April 2010.

6 See, for example, teacher despondency around the teaching of the Voortrekker Monument as heritage theme in a post-apartheid South Africa in C Kros, "Public history/heritage: translation, transgression, or more of the same?", African Studies, 69(1),April 2010,pp.63-77.

7 B Kompi, "Simplifying the assessment of heritage assignment" (Paper, South African Society for History Teaching (SASHT) Conference, Golden Gate, South Africa, 24 September 2010).

8 Interview with L Scott (Internal Moderator, Gauteng, Paper 2) and C O'Neil (Chief Examiner and Chief Assessor, Gauteng, Paper 2), Pretoria, 11 September 2010.

9 B Moreeng, "Exploring heritage in the classroom: towards debalkinising nation building" (Paper, SASHT Conference, Golden Gate, South Africa, 24-25 September 2010).

10 J Carruthers & S Krige, Heritage Studies: Only Study Guide for HSY306-Q (Pretoria, Unisa, 2004),pp.10-11.

11 DH: SCF 5: Q1 - LJ Sekalo, Pretoria; Q2 - A Mashamaite, Bochum.

12 DH: SCF 5: Q1 - LJ Sekalo, Pretoria.

13 Department of Basic Education (DoE), Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS ), 2010,pp.33-34.

14 Interview with L Scott and C O'Neil, Pretoria, 11 September 2010.

15 For more information on teacher training via ODL, see H Peraton (ed.), Distance Education for teacher training (New York, Routledge, 1993); P Murphy & A Zhiri (eds), Distance education in Anglophone Africa: experience with secondary education and teacher training (Washington DC, World Bank, 1992); R Neidorf, Teach beyond your reach: an instructor's guide to developing and running successful distance learning classes, workshops, training sessions and more (Medford, NJ, Information Today, c2006); C Vrasidas & GV Glass (eds), Online professional development for teachers (Greenwich, Conn., Information Age Publishers, c2004); D Hayes, In-service teacher development: international perspectives (Hertfordshire, Prentice Hall, 1997), HH Chikuya, "Teacher education within the context of open and distance learning in Zimbabwe: a case study" (Ph. D, Unisa, 2007); DR Bagwandeen, "A study of the provision of distance education for the upgrading and improvement of the qualifications of teachers in the province of Kwazulu-Natal" (D. Ed, Unisa, 1999).

16 P Marais, "Student teachers' experiences of teaching practice through ODL", Progressio, 32(2),2010,pp.181,184-185,197.

17 E du Plessis, "Students' experiences of work-integrated learning in teacher education", Progressio, 32(1),2010,pp.206-221.

18 P Marais, "Student teachers' experiences...", Progressio, 32(2),2010,pp.181,186,196-197.

19 The Unisa Short Course in School History Enrichment is accredited by SAQA and is offered at NQF Level 5.

20 For a critical reflection on the concept of "community" in community heritage projects, see E Waterton & L Smith, "The recognition and misrecognition of community heritage", International Journal of Heritage Studies,16(1-2),January-March 2010,pp.4-15; For debates around community engagement work in the heritage sector and community-heritage engagement as a means of control, see C Perkin, "Beyond the rhetoric: negotiating the politics and realising the potential of community-driven heritage engagement", International Journal of Heritage Studies, 16(1-2),January-March 2010,pp.107-122, and E Crooke, "The politics of community heritage: motivations, authority and control", International Journal of Heritage Studies, 16(1-2),January-March 2010,pp.16-29.

21 See Short Course in School History Enrichment promotional brochure; Unisa History Department website http://www.unisa.ac.za/Default.asp?Cmd=ViewContent&ContentID=157; DH: SCF 1: A Grundlingh (Chair of Department) - C Ware (Chairman of Coca-Cola, Africa), 12 May 1998.

22 For a detailed discussion of the research findings, see HJ Lubbe, "Life on the fringes: the role of the Unisa Short Course in School History Enrichment in empowering teachers", Historia, 55(1),2010,pp.125-140.

23 Respondents were given the choice between submitting their responses anonymously and providing their name. Except for one, all respondents chose the latter and gave permission to be quoted in publications flowing from the research.

24 Option A (History, Grades 11 & 12), Option B (History, Grade 10) and Option C (Social Sciences, Grades 8 & 9).

25 DH: SCF 2: Q20 - MB Motsinoni, Ga-Kgapane; Q7- ZA Gontsana, Mthatha; Q16 - SF Matsoku, Dendron; Q6 - DC Dube, Ekangala; Q10 - PD Leboea, Matatiele; Q11- MM Mailula, Polokwane; Q12 - LK Magagula, Sibuyile; Q13 - S Maluleke, Elliot; Q15 - VM Maphiri, Hamakuya; Q19 - NJ Mosetlhe, Taung Station, to mention but a few.

26 DH: SCF 2: Q1 - M Badat, Middelburg, Mpumalanga; Q25 - VH Ndlovu, Cato Ridge; Q27 - MZ Nkosi, Nongoma.

27 DH: SCF 2: Q10 - PD Leboea, Matatiele; Q12 - LK Magagula, Sibuyile; Q15 - VM Maphiri, Hamakuya; Q23 - T Mtshali, Kwangwanase.

28 DH: SCF 2: Q5 - B Da Silva, Escombe; Q10 - PD Leboea, Matatiele; Q11 - MM Mailula, Polokwane; Q29 - JA Peters, Phoenix; Q6 - DC Dube, Ekangala; Q24 - SL Mzila, Lady Frere; Q25 - VH Ndlovu, Cato Ridge; Q34 - TR Zindela, Dimbaza; SCF 3: M Badat, Middelburg, Mpumalanga, in a personal note (undated) included in an assignment.

29 SMS: NS Maxengana (student)/H Lubbe (researcher), December 2009 (69% improvement); DH: SCF 2: Q30 - ZB Poswa, Vanderbijlpark (between 60 % and 70 % improvement). Significantly improved pass rates were reported in a follow-up research project in 2010 when 12 of the 16 respondents (n=36; response rate 44,4%) reported significantly improved pass rates; the remaining 4 respondents either taught at schools where history had been phased out or worked in the heritage sector. See DH: SCF 12: items 1 to 16.

30 This refers to a convenience sample of 90 which represented all the teachers who had completed the Short Course between 2006 and 2009 and could be handled by only one researcher. Lack of human and financial resources made a quantitative analysis of the collected data impossible.

31 DH: SCF 2: Q24 - SL Mzila, Lady Frere; Q6 - DC Dube, Ekangala; Q21 - FS Motsoeneng, Three Rivers; Q36 - Anonymous; Q13 - S Maluleke, Elliot; Q9 - M Lancaster, Grahamstown.

32 DH: SCF 5: Student feedback (heritage), 2010.

33 The lecturer who invited student feedback on History I modules towards the end of 2010 reported a similar experience for probably the same reason.

34 DH: SCF 6: Student feedback (heritage), 2011.

35 DH: SCF 5: Q2 - A Mashamaite, Bochum.

36 DH: SCF 5: Q1 - LJ Sekalo, Pretoria.

37 DH: SCF 5: Q1 - LJ Sekalo, Pretoria; Q2 - A Mashamaite, Bochum.

38 DH: SCF 5: Q1 - LJ Sekalo, Pretoria.

39 DH: SCF 5: Q2 - A Mashamaite, Bochum.

40 DH: SCF 5: Q1 - LJ Sekalo, Pretoria; Q2 - A Mashamaite, Bochum.

41 TS van Eeden & JB Dewar, "Exploring evaluation practices in developing a distance educational DVD", Progressio, 32(2),2010,p.65.

42 See EO de Munnik, "Media-futurologie in afstandsonderrig", Progressio, 14(1),April 1992,pp.50-57; T Bates, Technology, open learning, and distance education (New York, Routledge, 1995); T Bates, Technology, e-learning and distance education (London & New York, Routledge, 2005); EO de Munnik, Listening and learning: a students' guide to the use of audio-print materials in distance education (Pretoria, Unisa, c1993).

43 See KL Harris, "To go on air or on tape?: the role of audio cassettes and radio broadcasts at Unisa", Progressio, 16(1),July 1994,pp.88-97; KP Quan-Baffour, "The introduction of audio cassettes in an integrated study package in solving the problems of adult distance education students in Lesotho (M. Ed, Unisa,1995).

44 See EO de Munnik, "Evaluating radio broadcasts", Progressio, 14(2),January 1992,pp.20-24.

45 See EO de Munnik, "Some ideas on the use of television in distance teaching", Progressio, 10(1),November 1988,pp.143-149; EO de Munnik, "First step towards educational broadcast television?", Progressio, 14(2),January 1992,pp.11-18.

46 For the advantages of video/DVD in practical skills training, see TS van Eeden & JB Dewar, "Exploring evaluation practices in developing a distance educational DVD", Progressio, 32(2),2010,p.67.

47 Use of myUnisa is currently characterised by "insufficient meaningful interaction" and a "lack of depth" in terms of e-learning. See B Mbatha & L Naidoo, "Problems hampering the collapse of distance in ODL", Progressio, 32(1),2010,pp.174-183.

48 In the first two years (1999 and 2000) the course attracted 120 and 90 enrolments respectively. Student numbers subsequently declined as a result of growing pressure on the historical discipline and the phasing out of history at many secondary schools across South Africa. However, course registrations remained relatively stable throughout the 2000s varying between 30 and 50 enrolments per year. See DH: Student statistics, 1995 to the present.

49 For more information on the advantages and disadvantages of MXit, see AA van Rooyen, "Integrating MXit into a distance education Accounting module", Progressio, 32(2),2010,pp.52-64.

50 HJ Lubbe, "Life on the fringes...", Historia, 55(1),2010,p.132.

51 For an overview of educational changes in South Africa after 1994, see DA Black, "Changing Perceptions of History Education in Black Secondary Schools with special reference to Mpumalanga, 1948-2008" (MA , Unisa, 2009), Chapter 5.

52 See National Curriculum Statement, Grades 10-12 (General), History (Pretoria, Department of Education, 2003); National Curriculum Statement, Grades 10-12: Subject Guidelines: History (Pretoria, Department of Education, 2008); Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS ) (Pretoria, Department of Basic Education, 2010).

53 HJ Lubbe, "Life on the fringes...", Historia, 55(1),2010,pp.130-1.

54 N Pereira, R Odendaal & H Lubbe (compilers), Practical Guide for History Teachers, Grades 11&12 (Pretoria, Unisa, 2007); N Pereira & H Lubbe (compilers), Practical Guide for History Teachers, Grade 10 (Pretoria, Unisa, 2008); R Odendaal, N Pereira & H Lubbe (compilers), Practical Guide for Social Science Teachers, Grades 8&9 (Pretoria, Unisa, 2008); Tutorial Letter 101for SCHE016 (Pretoria, Unisa, 2011).

55 For interesting arguments around the needs of more interpersonally oriented learners with an African cultural background, see M Qakisa-Makoe, "Reaching out: supporting black learners in distance education", Progressio, 27(1&2),2005,pp.44-61.

56 Tutorial Letter 101for SCHE016 (Option A), p.14; Tutorial Letter 101for SCHE016 (Option B), p.12; Tutorial Letter 101for SCHE016 (Option C), p.13.

57 See DH: SCF 8 (Assessor reports, 2010-2011).

58 DH: XMO Report for SCHE016, 2010.

59 DH: SCF 9 (Minutes of meetings with tutors): E-meeting with T Rossouw, 4 June 2010; meeting with J Moti and P Pillay, Laudium, Pretoria, 5 March 2011.

60 For critical reflections on the role of technology in ODL in view of huge disparities in terms of student access to technology, see JF Heydenrych & P Prinsloo, "Revisiting the five generations of distance education: quo vadis?", Progressio, 32(1),2010,pp.5,11,22-23; IM Ntshoe, "Realigning visions and missions of universities in a transbinary setting", Progressio, 32(1),2010,pp.27,39; MC Cant & CH Bothma, "The learning-technology conundrum: lecturers' perspectives", Progressio, 32(1),2010,pp.63,66-69; BT Mbatha & L Naidoo, "Problems hampering the collapse of distance in ODL", Progressio, 32(1),2010,p.182.

61 "First Aid for FET"(Pretoria, Unisa, 2007); "Short Cuts to Teaching Social Science" (Pretoria, Unisa, 2008); "Work Smarter Not Harder" (Pretoria, Unisa, 2008); "Tips for Teaching Heritage" (Pretoria, Unisa, forthcoming).

62 DH: SCF 10 (CD/DVD sales).

63 See "First Aid for FET" DVD and accompanying CD, insert 4.

64 See "First Aid for FET" DVD and accompanying CD, insert 5.

65 S Tiley, Mapungubwe: South Africa's Crown Jewels (Cape Town, Sunbird Publishing, 2004); TN Huffman, Mapungubwe: Ancient African Civilisation on the Limpopo (Johannesburg, Wits University Press, 2005).

66 See, for example, http://www.sahistory.org.za/pages/artsmediaculture/protest_art/archive/arch.htm; http://www.archivalplatform.org/, as accessed on 1 September 2010.

67 "Heritage investigation: Mapungubwe" designed by Short Course tutor T Rossouw, Crawford College, Pretoria, 2010.

68 See "Tips for Teaching Heritage" (Pretoria, Unisa, forthcoming); "Heritage investigation: Military Museum" designed by Short Course tutor T Rossouw, Crawford College, Pretoria, 2010.

69 KA Hlongwane, S Ndlovu & M Mutloatse (eds), Soweto '76 (Houghton, Mutloatse Arts Heritage Trust, 2006).

70 DH: SCF 7: V Rietbroek, Assignment 03 for SCHE016 (2010).

71 DH: SCF 7: J Sekalo, Assignments 03 and 07 for SCHE016 (2010).

72 See, for example, http://www.sahistory.org.za/pages/artsmediaculture/protest_art/archive/arch.htm; http://www.archivalplatform.org/, as accessed on 1 September 2010.

73 See http://www.archivalplatform.org/news/entry/criminalizing_struggle/, as accessed on 1 September 2010.

74 Blondie Makhene, "Amaqabane", Track 12 ("Siyaya").

75 Listen to Lucky Dube's "Think about the Children" (c. 1987/8), "Prisoner" (1989), "Captured Live" (1990), "House of Exile" (1991) and "Victims" (1993).

76 M Peters, "JPre looks to 2010, launches new album ["Listen Up"]", Cape Argus, 7 March 2009 (available at http://www.capeargus.co.za/index.php?fArticleId=4876735, as accessed on 20 July 2010).

77 Johannes Kerkorrel is the performing name of the late Ralph Rabie. "Kerkorrel" literally means "church organ" and "Gereformeerde" means "Reformed", referring to the Dutch Reformed Church.

78 A Grundlingh, "Skiet die (vul iets hier in)", Die Burger, 19 February 2011 (available at http://www.dieburger.com, as accessed on 14 April 2011).

79 Johannes Kerkorrel en die Gereformeerde Blues Band, "Eet Kreef" ["Eat Crayfish"], 1989; Various artists, "Voëlvry: Die Toer" ["Outlawed: The Tour"].

80 This refers to former Minister of Finance, Barend du Plessis, who used tax payers' money to finance the oppressive apartheid system.

81 See A Bezuidenhout, "From Voëlvry to De la Rey: Popular music, Afrikaner nationalism and lost irony" (available at http://www.litnet.co.za/cgi-bin/giga.cgi?cmd=print_article@news_id=11123&cause_id=163, as accessed on 26 August 2010); A Grundlingh, "Rocking the boat in South Africa? Voëlvry music and Afrikaans anti-apartheid social protest in the eighties", International Journal of African Historical Studies, 37(3), 2004, p. 483 ff; P Hopkins, Voëlvry: the movement that rocked South Africa (Cape Town, Zebra Press, 2006).

82 See E Gunner, "Jacob Zuma, the social body and the unruly power of song", African Affairs, 108(430),2009,pp.27-48.

83 Listen to albums such as "Lugsteuring"["Air Disturbance"](2004), "Monoloog in Stereo" ["Monologue in Stereo"] (2005), "Swanesang" ["Swan Song"] (2006) and "Antibiotika" ["Antibiotics"] (2008) and watch the documentary about the band entitled "Forgive them for they know not what they do" (2009).

84 See, for example, the statement by Advocate S Mancotywa (CEO of the National Heritage Council) in "National Heritage Council: criminalizing struggle songs is inconsiderate" (available at http://www.archivalplatform.org/news/entry/criminalizing_struggle/, as accessed on 1 September 2010); S Masondo, "ANC defends struggle songs", Sunday Times, 30 March 2010 and S Msomi, "It's time to sing 'Heal the Boer'", Sunday Times, 16 March 2010 (both available at http://www.timeslive.co.za, as accessed on 4 April 2011); R Azzakani, "Malema is onversetlik oor lied", Die Burger, 27 January 2011; J Botha, "Skiet die Boer is nes De la Rey", Die Burger, 25 February 2011; J Keogh, "Malema se lied 'nie uit die struggle'", Die Burger, 14 April 2011 (all available at http://www.dieburger.com, as accessed on 14 April 2011).

85 See "Tips for Teaching Heritage" (Pretoria, Unisa, forthcoming): Group work activity developed by R Odendaal, Johannesburg, 2011.

86 DH: Short Course File 4: Q5 - S Maluleke, Lady Frere.

87 See also R King, "Be passionate about history - marketing history to learners and parents", Yesterday&Today, Special Edition, 2006,pp.33-38.