Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versão On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.19 no.4 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2222-3436/2016/v19n4a4

ARTICLES

Antecedents to transformational community engagement in South Africa

Lauren Stirling; Anthony Wilson-Prangley; Gillian Hamilton; Johan Olivier

Gordon Institute of Business Science, University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

Firms face increasing societal pressures to act responsibly towards stakeholders, and community engagement is a key element of this response. While Bowen, Newenham-Kahindi and Herremans (2010) have found that community engagement strategies fall into the transactional, transitional and transformational categories, more research is needed. Nineteen semi-structured interviews were conducted with CSR practitioners, community beneficiaries and external experts across three companies from different sectors and geographically-associated South African communities.

Barriers to and enablers of transformational community engagement are identified and compared with points made in the literature. Prominent barriers identified include community expectation; the internal capacity of the company to engage properly with communities; and, according to a new finding in the literature, community educational levels. The most prominent enabler of engagement was relationship-building. Companies with dedicated CSR practitioners are able to engage more in the community. Regulatory dynamics are found to largely determine the differences across sectors. But there is the risk that engagement is symbolic rather than substantive. Eleven higher-order antecedents to transformational community engagement are then identified. A newly developed firm-oriented decision-making model is proposed for moderating these antecedents. The findings in the community and national context provide granular insight into an African operating environment.

Key words: strategy, community engagement, corporate social responsibility, stakeholder

JEL: M14, O35, 43

1 Introduction

Across many of Africa's emerging economies, including South Africa, the combination of the growing power of corporations and the developmental needs of the country have resulted in increasing expectations from both governments and society for companies to play a role in socioeconomic development (Edward & Tallontire, 2009; Halme & Laurila, 2009). In addition to the response to societal pressure, there is evidence that becoming more socially responsive could have a business return and could contribute to the competitive success of corporations (Moir, 2001; Wood, 1991; Porter & Kramer, 2006). Consequently, corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the imperative to contribute to socio-economic development have become increasingly important aspects of corporate strategy.

This strategic approach to CSR requires companies to understand and respond to a large, diverse set of stakeholders, such as consumers, employees, investors, governments, the environment a nd communities (Hildebrand, Sen & Bhattacharya, 2011; Vilke, 2011). Communities are key stakeholders and community engagement is a crucial component of stakeholder relations management, contributing as it does to the effectiveness of CSR (Bowen, 2007).

Bowen et al. (2010) outline a continuum of strategies that could be employed in community engagement, including transactional, transitional and transformational community engagement. At one end of the continuum is the most commonly-practised, philanthropically-based transactional engagement. At the other end is transformational engagement, a more proactive, participatory approach that involves developing partnerships and supportive leadership roles for communities, allowing the attainment of outcomes that may never have been reached before. Few companies are currently engaged in transformational community engagement despite its benefits.

Further, there has been little research into how firms could engage communities in transformational ways (Bowen, et al., 2010; Esteves & Barclay, 2011). This may be partly owing to the pressure to 'publish or perish', whereby getting good data on transformational engagement requires in-depth studies which are lengthier than studies on transactional or transitional engagement.

Ditlev-Simonsen (2010) calls for a better understanding of how companies put CSR into practice. In South Africa, as a consequence of disparities associated with Apartheid, as well as the mounting discontent with the provision of state services, communities are becoming increasingly confrontational, as seen in the thousands of service delivery protests that have taken place (Saba & van der Merwe, 2013) particularly in the case of the Marikana uprising (Chapple & Barnett, 2012). Companies ought to address the communities, as they have an obligation to assist in the country's development. Transformational community engagement seeks to 'change society' rather than simply 'giving back'. Considering the above issues, there is significant potential in this. If the antecedents to transformational community engagement were understood, then firms could focus their attention on moderating them and developing better outcomes.

Addressing the gap in existing research and the needs of business and society, this research aims to understand the antecedents that strengthen or weaken transformational community engagement in geographically-defined communities. It builds on the theoretical work of Bowen et al. (2010), with particular emphasis on the importance of the national context and the legal drivers of community engagement. Many of the findings here focus on the relationship interface between firms and communities. As such, there are some important findings for practitioners in the CSR and firm strategy fields.

Three research questions were explored. The questions were considered from an internal stakeholder (company employee) perspective and from an external stakeholder (community member and other interested third party) perspective. The first two were used in interviews to arrive at an understanding of the interviewees' perspectives on what weakens or strengthens transformational community engagement. These were:

1 What are the barriers to transformational community engagement?

2 What are the enablers of transformational community engagement?

While barriers and enablers can sometimes be seen as 'different sides of the same coin', following Hertzberg's two-factor theory of motivation, what motivates is not always simply the opposite of what demotivates (Robbins & Judge, 2015).

A further question was:

3 What are the antecedents to transformational community engagement and how could they be moderated?

In order to answer this question, higher-level themes were developed by pulling together lower-level barriers and enablers. This allowed for further appropriate simplification, so that the final model could be developed.

2 Literature review

2.1 Corporate social responsibility critiques

CSR is a broad field. It has been poorly defined and is consequently approached in different ways by those engaging with it, depending on their context. There is no universally accepted definition of CSR. Matten and Moon (2008) simplify this complex field by stating that CSR is a means of ensuring that companies are operating in a socially responsible manner as far as society is concerned. The role and relevance of corporate social responsibility has evolved considerably over time (Hildebrand et al., 2011). When CSR was initially discussed in the 1950s, the focus was on defining it (Carroll, 1991). However, from the 1980s onwards, there was a shift from defining CSR to attempting to measure its impact using frameworks and models to guide the creation of CSR strategies. More recently, companies have begun to realise that CSR activities could have a positive impact on financial returns (Williams, 2014) although evidence in South Africa is contradictory (Gladysek & Chipeta, 2010; Turyakira, Venter & Smith, 2014).

CSR has become a strategic imperative but it has been criticised for being corporate 'green-wash' and a cover for 'business as usual' (Littlewood, 2014). Critiques of CSR are aimed mostly at the philanthropic or charitable giving approaches, especially when these gestures fail to make a meaningful impact (Hamann, 2006). Additionally, the critics of CSR claim that it reduces social innovation and communities' ability to plan for the long term (Tracey et al., 2005). A further criticism is that businesses call themselves good citizens on the strength of their philanthropic offerings, despite the negative consequences of their business operations (Hamann, 2006). A further concern about the effectiveness of CSR programmes relates to companies' motives. The instrumental 'business-case' approach, particularly when CSR is voluntary, results in companies making choices based on the 'business-case' rationale, i.e. whatever will increase their long-term profitability (Esteves & Barclay, 2011; Littlewood, 2014). This could undermine what is best for society. There is some evidence that more substantive engagement with society (through, for example, transformational community engagement) results in the community's needs and resources being fully integrated into the firm's decision-making process (Gordon, Schirmer, Lockwood, Vanclay & Hanson, 2013).

2.2 Corporate social responsibility in South Africa

The contextual case for CSR in South Africa is motivated by a range of social challenges and inequalities brought about by the Apartheid regime (Hamann, 2004) and the emergence of new social problems. Tragic events, such as the uprising in Marikana in October 2012, are a result of these issues (Chapple & Barnett, 2012). Over and above social imperatives, CSR in South Africa has been legislated (Arya & Bassi, 2011; Hamann, 2006) through the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment scorecards (Hinson & Ndhlovu, 2011; DTI, 2007). This has been both hailed as proactive and forward-thinking and criticised for benefiting only a certain elite (Hamann, 2006; Patel & Graham, 2012; Ponte, Roberts & Van Sittert, 2007). Concern has been raised that it is becoming a tick-box exercise simply to meet measurement targets, losing the 'spirit' of the certification (Ponte et al., 2007). Development challenges in the community context and the state-mandated participation in CSR activities have resulted in the need for a different approach (Hamann, 2006). These contextual issues influence the dynamics of CSR and provide a theoretically useful domain in which to explore how community engagement occurs.

2.3 The community as a stakeholder

Companies are increasingly aware that they are no longer accountable to shareholders alone, and, in fact, have a myriad groups/individuals that could affect the successful running of a business (Freeman et al., 2004) . Carroll and Buchholtz (2008), as cited in Vilke (2011), note that the concept of 'society' in the CSR context is not fully recognised, so a stakeholder approach is necessary when developing a CSR strategy. Hildebrand et al. (2011) note that: 'At the heart of the strategic approach to CSR are the groups that have, or claim, ownership, rights, or interests in a corporation and its activities, past, present, or future' (Vallaster, Lindgreen & Maon, 2012). These include customers, suppliers, employees, investors, the communities in which they operate and the extent to which they care for the environment.

The focus of this research is on the last-mentioned stakeholder group: the community. Lee & Newby define community as a group of citizens drawn together by shared geography, interaction or identity (as cited in Bowen et al., 2010). This research focuses on the geographical community affected by a company owing to their proximity to its operations and specifically the geographic communities in which there is additional interaction with the company operations. Shaw (2007) argues that such localised CSR initiatives are more likely to be relevant and effective.

2.4 Community engagement

For this study, community engagement is defined as an activity that forms part of a corporation's wider stakeholder management programme and is part of the CSR activities related to a specific community of people (Bowen et al., 2010). Community engagement consists of a number of activities ranging from one-way information to the public, to two-way collaboration (Gordon et al., 2013). Community engagement potentially provides benefits for both the company and the community, with the company gaining legitimacy and managing social risk and the community gaining access to skills interventions, capacity-building, and improvements to social problems (Bowen et al., 2010; Gordon et al., 2013). In resource-reliant communities, such as mining towns, community engagement is a method of helping decrease dependency on the company and driving self-sufficiency (Littlewood, 2014).

A detailed analysis of over 200 academic, practitioner and knowledge sources by Bowen et al. (2010) was undertaken to determine how and why firms and the community benefit from community engagement strategies, and when different community engagement strategies are appropriate, resulting in what is defined as the 'continuum of community engagement'. A typology of three engagement strategies has been developed, viz. transactional, transitional and transformational engagement. The character of these strategies is detailed in Table 1 below.

Bowen et al. (2010) define the three forms of community engagement. Transactional engagement is based on 'giving-back' through community investment and information. 'Giving back' can include philanthropic donations and employee volunteering. It relies on one-way communication where interaction is occasional and the process and decision-making are controlled by the firm.

Transformational engagement is a synergistic process that aims at 'changing society' through joint decision-making and shared sense-making. Projects are managed by both the firm and respective communities, and community leadership is involved in the decision-making. Through the shared processes, outcomes are achieved that were unattainable without the community. Transformational engagement involves high levels of trust and relies on authentic dialogue, with frequent interactions amongst a more limited group of partners. Several case-based studies have been conducted on the effectiveness of various types of community programmes requiring 'transformational' engagement. These include Community enterprises in the UK (Tracey et al., 2005) and Corporate-community partnerships (Esteves & Barclay, 2011) in the Australian minerals sector.

Transitional engagement is an intermediate form of engagement between transactional and transformational forms in which engagement is substantive but synergy is not achieved. Like transformational engagement, it is characterised by two-way communication and higher levels of community involvement. The control of resources remains with the firm, but 'bridges are built' with communities. This form of engagement lacks the joint decision-making and shared sense-making of truly transformational engagement.

There are a number of observed complexities in the scholarship relating to community engagement. For example companies are often unsure as to what community engagement strategies are appropriate and what benefits they may provide (Bowen et al., 2010). If the benefits are not clear and shared, then effective adoption is not likely to be possible (Gordon, 2012). This is further intensified because many of the benefits are long-term and tend to be intangible. Frynas (2008) indicates that the approach used for consultation and the capacity of the firm to engage in this manner will affect the outcomes. Tracey et al. (2005) argue that we cannot assume that communities are homogeneous, and that power relations are often ignored, resulting in the 'community view' being that of the most powerful group. Esteves and Barclay (2011) note that, in order to have a corporate-community partnership, firms need to have a formal partnership agreement in place as well as the capacity for partnering.

In order to advance the field, a variety of antecedents that enable more transformational engagement have been researched and described. These include sharing the vision and strategy (Esteves & Barclay, 2011; Littlewood, 2014), commitment from key people (Vilke, 2011), identifying obstacles and agreeing on negotiable positions (Esteves & Barclay, 2011), being inclusive and building trust (Gordon et al., 2013), having an in-depth understanding of communities and the challenges they face (Littlewood, 2014), using national legislation to support efforts (Bowen et al., 2010) and developing long-term solutions that build capacity (Trarcey et al., 2005). Community members also need to feel involved in transparent decision-making (Littlewood, 2014), while relationships should be formed on the basis of mutual advantage (Tracey et al., 2005).

There has been a call for further research on these issues and for the elaboration of the antecedents in a diversity of contexts. This research seeks to identify the antecedents of transformational community engagement amongst three diverse sectors and companies in South Africa. It seeks specifically to identify practices that shift engagement strategies from transactional to transformational approaches.

3 Research approach

Three sectors were selected because they presented potentially different operating contexts. The research focussed on three companies and associated communities, one in each sector. This allowed for the triangulation of the findings when commonalities and differences emerged in the different contexts.

A wide range of companies was initially selected from the Johannesburg Stock Exchange's (JSE) Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) Index. The SRI Index ranks companies according to their performance against a set of triple bottom line measurement criteria, including 'community relations' and 'stakeholder engagement' (JSE, 2011). This list of suitable companies was further narrowed through an analysis of their annual reports. Shortlisting was done by means of scrutinising disclosures in the reports. Selected companies had to fulfil three requirements, including whether:

• their operations affected a 'geographic' community;

• they listed 'community' as a stakeholder; and

• community engagement was discussed in their sustainability reporting.

Three companies were then selected by virtue of the researchers' judgment being indicative (rather than unusual) in the broader sector in which they operated. These were from the mining, food production, and hotels/leisure industries. Sectoral differences were both anticipated and desired, as they illustrated common and different antecedent issues across different contexts.

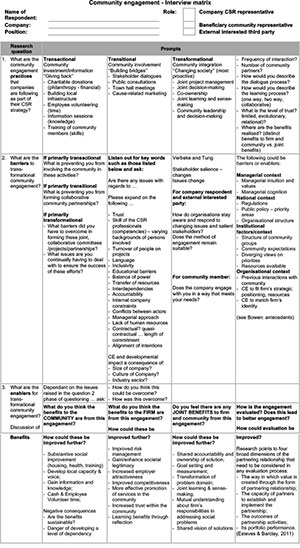

Despite significant research into the field of CSR, much less is known about community engagement. Research is needed on the emerging market and African contexts. But the work of Bowen et al. (2010) has advanced the field. A mixed deductive and inductive approach was followed. Based on work by Bowen et al. (2010), a semi-structured interview guide was deductively developed founded on the three types of community engagement (transactional, transitional and transformational). This is shown in Appendix 1.

After the interviews had taken place, transcripts were inductively coded in order to discern the emergent themes in an open and unbiased way. Barriers to and enablers of transformational community engagement were identified. This qualitative approach was underpinned by purposive sampling (Yin, 2003; Saunders & Lewis, 2012) . This approach aligns with recent research in this area (Esteves & Barclay, 2011; Gordon et al., 2013; Tracey et al., 2005).

Sixteen of the interviewees included company employees and community members from the geographical community in close proximity to the company. These were selected through snowball sampling. Snowball sampling is appropriate in cases like this, when access requires a degree of trust and there are limited numbers of respondents (Atkinson & Flint, 2001). In the companies studied the method also allowed for a cross section of interviewees from the companies and communities concerned. In addition to the interviews cited above, three experts on socioeconomic development or CSR were interviewed.

The interview method was face-to-face in all but three of the nineteen cases (when phone interviews had to be conducted). Each respondent was given an informed consent letter that included a concise and clear description of the purpose, scope and intended outcomes of the research. Ethical clearance was obtained through the university process. Community members interviewed were at times limited in their responses because of language differences, and, in two cases, a translator was necessary. Interpreter bias may have occurred but this was managed through a process in which all the interviews were supplemented with secondary data from the annual reports and policy documents of these companies.

The 19 interviews, ranging in length from 30 minutes to an hour, were recorded and transcribed. Copies of the interview transcripts were sent back to the respondents to allow them to check for accuracy and ensure the validity of the data. Data analysis involved selecting, simplifying, and transforming the data, using Atlas-ti, where interviews were initially coded for key words. Codes were grouped into sub-themes and then the final themes were presented. The data analysis process followed the model outlined by Miles and Huberman (1984), which consists of data reduction, data display and a conclusion, drawing and verification. Key issues, commonalities and divergences were noted. The barriers and enablers were found to occur in three locations:

• inside the firm, which we labelled the organizational context;

• internal to the community, which we labelled the community context;

• in the overlapping relationship between the firm and the community, which we labelled the relationship context.

Barriers and enablers were positioned in one of the three contexts in accordance with the judgment of the research team.

In response to research question three, the barriers and enablers were further refined and higherorder themes were developed. This process led to a merging of the barrier and enabler categories as joint 'antecedents' to community engagement. A final model was then developed that stimulated discussion on how firms could moderate these antecedents.

The main limitations of this study are associated with the snowball method of sampling and the limited number of companies selected. While snowball sampling has advantages, there is the risk of a biased representative voice owing to selection bias associated with the subjective referral from early interviews. This was managed by triangulating the views across the different interviews and the companies. Because three companies and their associated communities were studied, the inferences from this study should be considered with caution. It can be understood as a contribution to debates, but future studies should include more sectors across different countries. In terms of the number of interviews, there were only four respondents for the mining company and six for each of the others. However, by interviewing CSI specialists, community representatives and interested external parties, the research aimed to minimise interviewee bias and obtain a balanced view of current practices.

4 Findings

4.1 Interviewee description and cross-sector differences

The interviews (Table 2) were with a heterogeneous group of nineteen stakeholders involved in community engagement across the three companies and, for the experts, in broader CSR issues.

An overview of the policies, management and drivers for CSR, and the resultant practices across each of the companies interviewed are discussed below. Given that they span three sectors, varying internal and external factors influencing practice are present.

In the metals and mining sector, stakeholder engagement is formally legislated. In order to obtain and retain a licence to operate, the state requires mines to develop, submit and implement Social and Labour Plans (SLPs), and comply with the guidance and funding targets set out in the Mining Charter (MC) of 2010. Community engagement is listed in the mining company's report as both a material issue and a risk. The company studied has a dedicated department that focuses on community engagement, which ranges from philanthropic CSI donations and projects through to collaborating and partnering with local municipalities in a transformational way in the form of joint decision-making on the development of the area.

The food production company interviewed operates in close relationships with the farming communities that provide the raw crops for processing in the various mills around the country. The communities on which they geographically make an impact are the farming community and the communities around the mills. Community engagement is focused on the supply chain and relates particularly to South Africa's food security. Corporate philanthropy is not as prescriptively legislated as mining. Consequently, CSR occurs at a local level in a more transactional manner through requests brought to the company or through marketing initiatives that build the brand. Corporate philanthropy is overseen from head office, but smaller donations are managed by HR at the individual operations in response to requests.

The hotel and leisure company interviewed invests in and manages businesses in the hotel, resorts and gaming industries both in South Africa and internationally. Engagement with community-based groups is focused on the on-going support of enterprise development, charities and social action organisations, while philanthropic contributions are focused on projects relating to health and welfare, education and community development. In some instances, the business units have a manager dedicated to community engagement, and in others this portfolio is an additional job. The legislative requirements of the company's gaming licence require that money is spent within the province of the registering gaming board. This becomes an issue, as in some cases the business unit is located on the boundary of two provinces and the communities on its doorstep are not in the licence-providing province.

Table 3 gives an overview of how the company reports define community engagement. In practice, the three companies exhibited a range of engagement practices with all three engaging in transactional projects, and all attempting to involve the community in some way for transitional engagement. There were only a few cases of real transformational engagement, which were mostly in the mining company through its interaction with the local municipality.

4.2 Barriers to transformational community engagement

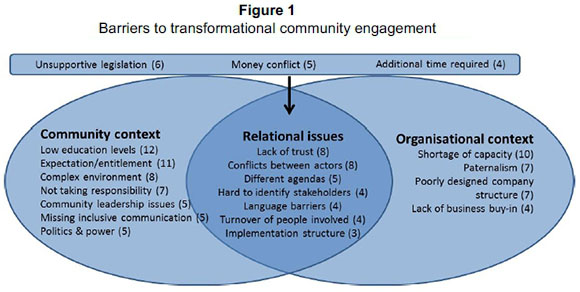

The respondents from the three companies, and the experts interviewed, listed twenty-one categories of barriers to transformational engagement, each reflecting the complex nature of CSR work. These were grouped according to three contexts within which the barriers lie and included the community context (seven barriers), the corporate context (four barriers), the relational context (seven barriers) and three cross-cutting barriers. Relational barriers refer to the barriers that were at the intersection of the company and community relationship. Figure 1 below illustrates the barriers.

The most frequently cited barrier between companies and the communities relates to the educational levels of the community members. This included levels of literacy and the lack of formal education, the inability to read instructions or engage with someone with higher levels of understanding, and lacking the appropriate skills to carry out projects.

HL3: Another thing that comes in, some communities don't know how to read, so you cannot by all means send them materials and tell them to read them. So you've got to be personally, physically training them, those are some of the challenges.

In the Southern African context, with a history of developmental aid and social grants, there is a perception that communities expect to be assisted and receive hand-outs. Eleven of the nineteen interviewees noted that the notions of expectation or entitlement hinder their efforts to develop joint projects. Contradicting this, one respondent raised the point that the 'entitlement' argument is both patronising and paternalistic.

Exp3: I mean I have my own personal view that the entitlement sort of argument around entitlement [sic] is quite a patronising and colonial approach, well, paternalistic approach, to development.

Of all the organisational context barriers, company capacity is mentioned most often across all the companies and by all three experts. Capacity relates to not having the internal human and/or financial resources and the requisite skills to manage engagement and CSR, as well as to monitor and evaluate the impact of the engagement. The lack of experience on the part of CSR practitioners, or people with the CSR profile, adds to this capacity issue.

MM1: Yes it can be very difficult if not managed properly, that's why we need specific skills on the portfolios for socio-economic development.

4.3 Enablers of transformational community engagement

Results from the interviews reveal that there are fifteen different enablers to transformational community engagement. Many of the frequently-cited enablers are within the organisations' sphere of influence. These are listed in Figure 2.

Among the enablers cited for transformational community engagement, intimate involvement was highlighted. This entails becoming closely involved in the community and the project so as to understand the role players, the context and the personal hierarchies and capabilities of the stakeholders involved.

HL2: We have for example within my committee; we have one of the guys who actually sits in the community committee, as a committee member. We have two other members who are also leaders within their community. It's just an eye opener that the information they are able to bring in terms of the needs that come from the various communities, it just opens our eyes.

In order to have transformational community engagement, respondents across the companies state that the engagement has to be designed with a long-term, sustainable focus, with several respondents stating the old adage of 'teach a man to fish', thus promoting giving a hand-up rather than a hand-out. Short-term projects are necessary and useful in building community trust and acceptance. However, once this has been achieved, long-term sustainable projects are necessary for developmental impact.

The organisation has to ensure community involvement. Companies need to understand that communities know what they want and what they need to spend their money on, and that the company ought to respect people's decision-making when it comes to their own lives.

Exp3: It's the community needs [sic] to drive the project themselves, they are engaged else it's never going to work.

5 Discussion

5.1 Comparison of barriers found in research and literature

Table 4 outlines the barriers identified and the associated literature.

A few issues are noted. Many of the barriers identified in the interviews have previously been noted in other case studies, some more prominently than others. The least prominent barriers in the literature relate to educational barriers, language barriers, money conflict, the turnover of people involved and issues related to the effectiveness of the community leader/liaison. Although these are not unique to South Africa, they are, in all likelihood, exacerbated by the developing world context, cultural diversity, high Gini coefficient and the history of segregated education. Many of these undocumented barriers exist in the community context. These findings extend the work by Bowen et al. (2010).

5.2 Comparison of enablers found in research and literature

Table 5 outlines the enablers found and the literature.

The attitude and approach to engagement taken by the organisation are key to its success. Many of the enablers are within the company's sphere of influence, highlighting the role of managerial perception by Bowen et al. (2010) and Reyers, Gouws & Blignaut (2011). For example, ethics could influence the direction of community engagement (Coldwell, 2010) but should be understood in its African context (Murove, 2005). According to the respondents, if transformational engagement is to take place, there has to be buy-in from the organisation and the development of a dedicated CSR department, with the necessary human and resource capacity to enable effective engagement in the complex community environment. As discussed in the above section, Sharp (2006) notes that we need more experts and fewer staff members with varied portfolios and CSR as an additional job, to enable this to happen (Sharp, 2006).

Esteves and Barclay's (2011) findings are further supported by this study, i.e. that organisations need system/process clarity and monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. The findings also support Littlewood's (2013) argument for genuine community involvement, where the community gains buy-in and alignment with the company.

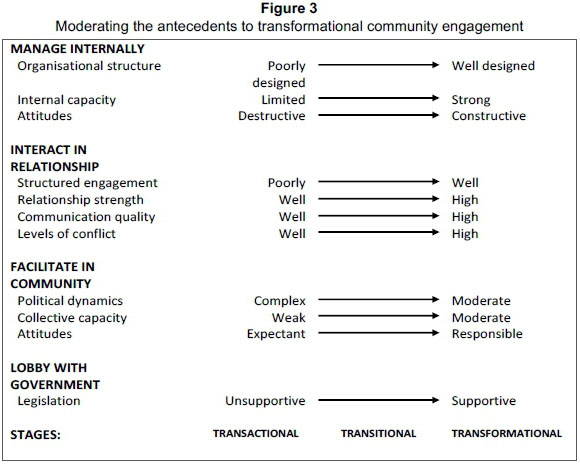

6 Moderating the antecedent to transformational community engagement

We were influenced by the Collaborative Value Creation framework (Austin & Seitanidi, 2012a; Austin & Seitanidi, 2012b) as a response to the call for a common and more precise vocabulary. This framework is built around a spectrum for Collaborative Value Creation in the context of cross-sector collaboration between business and non-profit organisations. They see four phases of engagement, ranging from Philanthropic to Transformational. The spectrum includes a range of variables that assist in understanding the levels of engagement. In a way similar to that in which they develop their framework, we developed our own spectrum based on the higher-order set of antecedents described below.

The language of barriers and enablers was useful in the interview process (as interviewees could easily conceptualise a response) and identified issues aligned to an extent with the literature (as detailed above). An enabler is not always the inverse of a barrier but it is evident that some of the barriers and enablers to transformational community engagement can be seen as 'two sides of the same coin'. For example, 'lack of trust' is a barrier and 'trust and relationship development', an enabler. Question three therefore focussed on identifying a more conceptually-clear set of higher order antecedents to transformational community engagement.

A final coding process merged the barriers and enablers into a set of antecedents to transformational community engagement. This was done by combining the lists and removing duplicate issues. Then connected barriers and enablers were merged into higher-level themes wherever possible. For example, the barriers of 'missing inclusive communication' and 'language barriers' were merged with enablers of 'communication', 'sharing the vision/benefits' and 'understanding what the community wants/needs' into a new higher-order label of 'Communication Quality'.

These higher-order labels are then illustrated on a spectrum with transactional community engagement at one end, transitional community engagement in the middle and transformational community engagement at the other end. Antecedents are placed on the spectrum with different levels. For example, in the case of 'Communication Quality', this can vary from low to high.

Finally, the eleven high-level antecedents were reorganised into a more logical flow for management decision-making, with a proposed four areas for managerial involvement based on the previously identified company context, relationship context, community context and the broader context. A final model is presented for managerial decision-making. This model is illustrated in figure 3 below and is described thereafter.

6.1 Manage internally

Firms have direct control over their own organisations. There are three antecedents to transformational community engagement that need to be managed in the company context. The first relates to the organizational structure. Clarity regarding systems and processes for community engagement are essential (Bowen et al, 2010). A dedicated CSR department can ensure that focussed capability exists and that relationships on the company side can be maintained. The metals and mining company, with its dedicated CSR department, listed fewer barriers than did the other companies and the experts. With a capacitated CSR department, the challenges of internal capacity and destructive attitudes were reduced and relationships with the community were strengthened (for example, by overcoming language barriers).

Secondly, substantive internal capacity is needed. This includes the capacity to handle communication, the capacity to partner, and the capacity to handle the monitoring and evaluation of progress. This is well documented in the literature (Esteves & Barclay, 2011). It also allows the dynamics that show up in relationships with the community to be managed (such as those in the Interact in Relationship and Facilitate in Community contexts). Thirdly, the attitude of company management is crucial and can range from destructive attitudes to constructive, committed and respectful attitudes. Particularly destructive attitudes that must be avoided include paternalism (Tracey et al, 2005) as well as a lack of commitment to buy-in. Buy-in can be built by more specifically outlining the benefits (Gordon, 2012).

6.2 Interact in relationship

Firms have less control in their relationships with the community but they still engage directly and can influence the results in what we previously labelled as the relational context. Here, there is an opportunity to influence four antecedents to transformational community engagement. Many of these issues that interact and merge into one another are generally of an interpersonal nature. First, engagements need to be structured well, for example by focusing on specific projects together and by ensuring continuity of participants from firm and community sides. Formal agreements can enable progress (Esteves & Barclay, 2011). Secondly relationships need to be strengthened and trust has to be built. Trust appeared as both a barrier (in its absence) and an enabler (in its presence) to transformational community engagement and is prominent and crucial. Intimate involvement allows for in-depth understanding (Littlewood, 2013). Thirdly, the quality of communication can be managed by focusing on understanding needs (Littlewood, 2013) and sharing visions (Gordon et al., 2013). Language skills are essential, as communication is often complicated by language barriers. Finally, conflict can be expected because of the different agendas (Bowen et al., 2010), miscommunication and varying attitudes. The level of conflict has to be maintained at moderate levels.

6.3 Facilitate in community

Firms cannot control events and dynamics among community members. However, they can facilitate and indirectly nurture the key dynamics that could help the firm move from transactional to transformational community engagement. There are three antecedents in the community context with which firms need to work. None of these antecedents is easy to moderate, because firms have only indirect influence over them.

Firms can help to build the collective capacity of communities from weak to moderate in terms of the ability to engage with company initiatives. Communities in the context of South Africa will always struggle with the capacity to engage but these struggles could be reduced. Broader low educational levels have to be raised and specific skills must be taught so that community members can engage productively. The significance of educational levels is a new finding and is not evident in the existing literature.

Then firms need to nudge community attitudes from the expectant and entitled towards a sense of shared responsibility and willingness to work together (Bowen et al., 2010). False hope and dependence should not be created in the communities, but there should rather be a realistic set of expectations. Finally, communities are prone to internal political conflict and tension among the leaders. Western CSR does not take into account conflicts between local actors (Jeppesen & Lund-Thompson, 2010). Firms should avoid further complicating the existing generally high levels of social and political complexity in communities. An awareness of key political dynamics is essential.

6.4 Lobby with Government

Firms have even less control over the development of legislation. But evidence from these findings shows the crucial importance of legislation as either a supportive enabler or an unsupportive barrier to transformational community engagement. For example, the hotel and leisure company said that the requirements of their gaming licence is a barrier, as it restricts the area of their CSR expenditure to the province of issue, not to the most salient geographical communities affected by the operations owing to proximity - and where they need to build legitimacy. The metals and mining company listed legislation, such as the requirements of the mining charter, as an enabler, because it clarifies the expectations of how the mine should contribute to the local community, thus reducing issues like business buy-in and stakeholder identification. Concern is raised around tick-box exercises (Hamann, 2006; Hinson & Ndhlovu, 2011) but we find that voluntary CSR is not sufficient to bring about a move to transformational community engagement (Bowen et al., 2010).

7 Conclusion

Addressing the call by Bowen et al. (2010), this paper provides a granular insight into stakeholders' views on community engagement practices in three different firms and communities from three different sectors in South Africa.

Barriers and enablers to transformational community engagement are first identified. These are then compared with the literature and some particular issues emerge in the context studied. The prominent barriers to community engagement include community members' educational levels; community expectation; and the internal capacity of the company to properly engage with communities. The most prominent enabler of engagement was relationship-building, as companies with dedicated CSR practitioners are able to become more engaged with the community.

Then eleven higher-order antecedents of transformational community engagement are identified. These are placed on a spectrum and a newly-developed model for moderating these antecedents to transformational community engagement is proposed. This decision-making model is presented to aid company managers. It is argued that firms can moderate these variables to shift the levels of community engagement from transactional to transitional and then transformational levels.

While Bowen et al. (2010) focus mostly on managerial perception, the evidence here is that capacity (or capability) is at least as important, if not more important than perception. Transitional and transformational engagement in South Africa seems to owe largely to the enabling pressure of the legal and institutional environment. This further confirms the findings by Bowen et al. (2010) on national context. If policy-makers want to see business play a greater role in development, they should consider how best to legislate for CSR. But Bowen et al. (2010) are correct in identifying the risk in this process where symbolic rather than substantive engagement occurs.

The overall view of the interviewees was that community engagement by South African companies is still primarily transactional in nature, despite their believing that transformational engagement is beneficial in normative and instrumental terms. These findings support Lee's (2011) institutional and stakeholder theory to explain how firms choose their CSR strategy. Further research linking the different forms of community engagement with company competitiveness is needed, especially that linking more closely with African and South African cases (Turyakira, Venter & Smith, 2014).

References

ARYA, B. & BASSI, B. 2011. Corporate social responsibility and broad-based black economic empowerment legislation in South Africa: Codes of good practice. Business & Society, 50(4): 674-695. [ Links ]

ATKINSON, R. & FLINT, J. 2001. Accessing hidden and hard-to-reach populations: Snowball research strategies. Social Research Update, 33(1):1-4. [ Links ]

AUSTIN, J.E. & SEITANIDI, M.M. 2012a. Collaborative value creation: a review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses: Part I. Value creation spectrum and collaboration stages. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(5):726-758. [ Links ]

AUSTIN, J.E. & SEITANIDI, M.M. 2012b. Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses. Part 2: Partnership processes and outcomes. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(6):929-968. [ Links ]

BOWEN, F. 2007. Corporate social strategy: Competing views from two theories of the firm. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(1):97-113. [ Links ]

BOWEN, F., NEWENHAM-KAHINDI, A. & HERREMANS, I. 2010. When suits meet roots: The antecedents and consequences of community engagement strategy. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(2):297-318. doi:10.1007/s10551-009-0360-1. [ Links ]

CAROLL, A. B. 1991. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business horizons, 34(4):39-48. [ Links ]

CHAPPLE, I. & BARNETT, E. 2012, September 14. What's behind South Africa's mine violence? CNN. Online News. http://www.cnn.com/2012/08/17/world/africa/marikana-south-africa-mine-shootings [accessed June 2015]. [ Links ]

COLDWELL, D. 2010. A road to organisational perdition? Business ethics and corporate social responsibility. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 13(2):190-202. [ Links ]

DITLEV-SIMONSEN, C. 2010. From corporate social responsibility awareness to action? Social Responsibility Journal, 6(3):452-468. [ Links ]

DTI. 2007. February 9. Broad-based black economic empowerment codes of good practice. Department of Trade and Industry. http://www.thedti.gov.za/economic_empowerment/bee_main_codes.jsp [accessed June 2015]. [ Links ]

EDWARD, P. & TALLONTIRE, A. 2009. Business and development-towards re-politicisation. Journal of International Development, 21(6):819-833. doi:10.1002/jid.1614. [ Links ]

ESTEVES, A.M. & BARCLAY, M.A. 2011. New approaches to evaluating the performance of corporate-community partnerships: A case study from the minerals sector. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(2):189-202. [ Links ]

FREEMAN, R.E., WICKS, A. C. & PARMAR, B. 2004. Stakeholder theory and "The corporate objective revisited". Organization Science, 15(3):364-369. [ Links ]

FRYNAS, J.G. 2008. Corporate social responsibility and international development: Critical assessment. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 16(4):274-281. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8683.2008.00691.x. [ Links ]

GLADYSEK, O. & CHIPETA, C. 2010. The impact of socially responsible investment index constituent announcements on firm price: Evidence from the JSE. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 15:429-439. [ Links ]

GORDON, M. 2012. Improving social outcomes in sustainable forest management: Community engagement and commitment to corporate social responsibility by Australian forest companies. http://eprints.utas.edu.au/16734/2/whole-Gordon-thesis-ex-pub-mat.pdf [accessed December 2014]. [ Links ]

GORDON, M., SCHIRMER, J., LOCKWOOD, M., VANCLAY, F. & HANSON, D. 2013. Being good neighbours: Current practices, barriers, and opportunities for community engagement in Australian plantation forestry. Land Use Policy, 34(0):62-71. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.02.005. [ Links ]

HALME, M. & LAURILA, J. 2009. Philanthropy, integration or innovation? Exploring the financial and societal outcomes of different types of corporate responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(3):325-339. [ Links ]

HAMANN, R. 2004. Corporate social responsibility, partnerships, and institutional change: The case of mining companies in South Africa. In Natural Resources Forum, 28:278-290. [ Links ]

HAMANN, R. 2006. Can business make decisive contributions to development? Towards a research agenda on corporate citizenship and beyond. Development Southern Africa, 23(2):175-195. doi:10.1080/03768350600707587. [ Links ]

HILDEBRAND, D., SEN, S. & BHATTACHARYA.C. 2011. Corporate social responsibility: a corporate marketing perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 45(9/10):1353-1364. [ Links ]

HINSON, R., & NDHLOVU,T. 2011. Conceptualising corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate social investment (CSR): The South African context. Social Responsibility Journal, 7(3):332-346. doi:10.1108/17471111111154491. [ Links ]

JEPPESEN, S. & LUND-THOMSEN, P. 2010. Special issue on "New perspectives on business, development, and society research." Journal of Business Ethics, 93(2):139-142. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0557-3 [ Links ]

JSE. 2011. Johannesburg stock exchange SRI index: Background and selection criteria 2011. JSE and EIRIS. http://www.jse.co.za/About-Us/SRI/Criteria.aspx [accessed June 2015]. [ Links ]

LEE, M.D. 2011. Configuration of external influences: The combined effects of institutions and stakeholders on corporate social responsibility strategies. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(2):281-298. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-0814-0 [ Links ]

LITTLEWOOD, D. 2013. "Cursed" communities? Corporate social responsibility (CSR), company towns and the mining industry in Namibia. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(1):39-63. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-1649-7. [ Links ]

MATTEN, D. & MOON, J. 2008. "Implicit" and "explicit" CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 35(2):404-424. [ Links ]

MILES, M.B. & HUBERMAN, A.M. 1984. Drawing valid meaning from qualitative data: Toward a shared craft. Educational Researcher, 13(5):20-30. [ Links ]

MITCHELL, R.K., AGLE, B.R. & WOOD, D.J. 1997. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: defining the principle of who and what really counts. The Academy of Management Review, 22(4): 853-886. [ Links ]

MOIR, L. 2001. What do we mean by corporate social responsibility? Corporate Governance, 1(2):16-22. [ Links ]

MUROVE, M.F. 2005. The voice from the periphery: Towards an African ethics beyond the western heritage. SAJEMS, 8(3). [ Links ]

PATEL, L. & GRAHAM, L. 2012. How broad-based is broad-based black economic empowerment? Development Southern Africa, 29(2):193-207. [ Links ]

PONTE, S., ROBERTS, S. & VAN SITTERT, L. 2007. "Black economic empowerment", Business and the state in South Africa. Development and Change, 38(5):933-955. [ Links ]

PORTER, M. & KRAMER, M. 2006. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and crporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 78-93. [ Links ]

REYERS, M., GOUWS, D. & BLIGNAUT, J. 2011. An exploratory study of motivations driving corporate investment in voluntary climate change mitigation in South Africa. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 14:92-108. [ Links ]

ROBBINS, S.P. & JUDGE, T.A. 2015. Organizational behaviour. (16th ed.) Boston: Pearson. [ Links ]

SABA, A., & VAN DER MERVE, J. 2013. January 22. Revealed - the true scale of SA service delivery protests. Media24 Investigations. Online News. http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/SA-has-a-protest-every-two-days-20130121 [accessed November 2016] [ Links ]

SAUNDERS, M. & LEWIS, P. 2012. Doing research in business and management: An essential guide to planning your project. (1st ed.) London: Pearson Education Limited. [ Links ]

SHARP, J. 2006. Corporate social responsibility and development: an anthropological perspective. Development Southern Africa, 23(2):213-222. doi:10.1080/03768350600707892. [ Links ]

SHAW, H. 2007. The role of CSR in re-empowering local communities. Social Responsibility Journal, 3(2):11-2. [ Links ]

TRACEY, P., PHILLIPS, N. & HAUGH, H. 2005. Beyond philanthropy: community enterprise as a basis for corporate citizenship. Journal of Business Ethics, 58(4):327-344. doi:10.1007/s10551-004-6944-x. [ Links ]

TURYAKIRA, P., VENTER, E. & SMITH, E. 2014. The impact of corporate social responsibility factors on the competitiveness of small and medium-sized enterprises. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 17(1):157-172. [ Links ]

VALLASTER, C., LINDGREEN, A. & MAON, F. 2012. Strategically leveraging corporate social responsibility:a corporate branding perspective. California Management Review, 54(3):34-60. [ Links ]

VERBEKE, A. & TUNG, V. 2013. The future of stakeholder management theory: A temporal perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(3):529-543. [ Links ]

VILKE, R. 2011. CSR development problems in Lithuania: evaluation of promoting and hindering factors. Social Responsibility Journal, 7(4) :604-621. [ Links ]

WILLIAMS, B. 2014. Changing the face of corporate social responsibility. http://www.prsa.org/Intelligence/Tactics/Articles/view/10593/1091/Changing _the_Face_of_Corporate_Social_Responsibility[accessed July 2014]. [ Links ]

WOOD, D. 1991. Corporate social performance revisited. Academy of Management Review, 16:691-718. [ Links ]

YIN, R.K. 2003. Case study research: Design and methods (Vol. 5). Sage. 2. [ Links ]

Accepted: April 2016

Appendix 1: Interview questionnaire matrix