Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versión On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.19 no.2 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2222-3436/2016/v19n2a2

ARTICLES

"I would rather have a decent job": Potential barriers preventing street-waste pickers from improving their socio-economic conditions1

Kotie ViljoenI; Phillip BlaauwII; Rinie SchenckIII

IDepartment of Economics and Econometrics, University of Johannesburg

IISchool of Economics, North-West University

IIIDepartment of Social Work, University of the Western Cape

ABSTRACT

As a result of the high levels of unemployment in South Africa, many unskilled people are forced to resort to a variety of income-generating activities in the informal economy. The activity of collecting and selling recyclables presents virtually no barriers to entry, making it a viable option. Very little research focusing on street-waste pickers has been undertaken, and, when it has been conducted, it has mostly taken the form of case studies. This paper reports the results of the first countrywide research into the potential barriers that prevent street-waste pickers from improving their socio-economic circumstances. The study used a mixed-method approach. Structured interviews were conducted between April 2011 and June 2012 with 914 street-waste pickers and 69 buy-back centres in 13 major cities across all nine provinces in South Africa. Low levels of schooling, limited language proficiency, uncertain and low levels of income, as well as limited access to basic social needs make it difficult for waste pickers to move upwards in the hierarchy of the informal economy. The unique set of socio-economic circumstances in which street-waste pickers operate in the various cities and towns in South Africa make the design of any possible policy interventions a complex one. Policymakers will have to take note of the interdependence of the barriers identified in this research. Failing to do so may cause policies that are aimed at supporting street-waste pickers to achieve the exact opposite, and, ironically, deprive these pickers of their livelihood.

Key words: informal economy, street-waste pickers, recycling

JEL: J46, O17

1 Introduction

A Colombian waste picker once said, "If we were any poorer, we'd be dead" (Ballve, 2008:1). Along with 1 per cent of the world's urban population, collecting and selling recyclable waste has become alternative informal employment for at least 37,000 people in South Africa (Langenhoven & Dyssel, 2007). Most of these people form part of the semi-skilled or unskilled portion of the labour force that is unable to find employment in South Africa's formal economy in the face of persistently high rates of unemployment (fluctuating between 24 and 26 per cent in the period 2009 to 2015). Their only alternative is to explore the possibilities of self-employment in the informal economy. The unemployed resort to different strategies to survive and informal economic activities, such as waste picking, are one of these strategies (Theron, 2010:1).

Waste pickers are broadly defined in the literature as small-scale, self-employed people who are mostly active in the urban informal economy (Hayami, Dikshit & Mishra, 2006:42; Schenck & Blaauw, 2011b). Theron (2010:1) confirms this, stating: "Most waste pickers have created their own jobs, and work for themselves: in other words they are self-employed." Waste is collected either for their own use or to sell (Samson, 2010) to higher-level traders and/or buy-back centres (BBCs) in order to earn a living. Waste is therefore a livelihood for the unemployed.

The terminology used to refer to people who collect and sell recyclable waste reflects and forms attitudes and perceptions regarding these people (Samson, 2010). They are referred to as "waste pickers", "scavengers", "waste recyclers", "garbage pickers" or, on a more positive note, as "waste salvagers" and "reclaimers" (Chvatal, 2010; Samson, 2010). We prefer the most commonly used term "waste pickers", as it describes the person's actions exactly. Most waste pickers in the informal economy earn a very low income for their work and effort, and their socio-economic conditions and working conditions remain appalling. Many also face chronic poverty despite their attempts to generate a livelihood in the informal economy (Masocha, 2006:839).

Attempts to earn a living in the informal economy are diverse. On the one hand, activities in the informal economy can be of a survivalist nature, such as day labouring or other casual, temporary or unpaid jobs, street trading, subsistence agriculture, or selling recyclable waste. The "informal sector" can also refer to the unofficial nature of business activities in order to avoid taxes or the effects of labour legislation.

The informal economy can furthermore be divided into upper-tier and lower-tier activities. The segmentation of the informal economy into a primary sector, or "upper tier", which is more organised and provides higher income-earning potential, and a secondary sector, or "lower tier", that is less organised and has a lower income-earning potential making the informal economy a complex phenomenon (Lehmann & Pignatti, 2007:3; Wills, 2009:2). Maloney (2004:1159) refers to the upper- and lower-tier activities as "voluntary entry" and "involuntary entry" into the informal economy, respectively.2 The upper-tier activities attract people who enter the informal economy voluntarily in the expectation that their earnings will be higher in the informal economy than in the formal economy (Fields, 1990:66; Günther & Launov, 2012:89). Entry into the lower-tier activities is involuntary and such activities are only performed by those who cannot find work in the formal labour market and who do not meet the capital and skills requirements for the activities of the upper-tier, self-employment informal economy (Günther & Launov, 2012:89).

The lower-tier activities are seen as the disadvantaged segment of the informal economy. Activities at this level involve the poor and include single street traders, micro-enterprises and subsistence farmers (Chen, 2012:8; Djankov, Lieberman, Mukherjee & Nenova, 2002:4; Launov & Günther, 2006:11 ; Viljoen, 2014). No aspirant jobseeker would like to perform these activities, as they do not generate sufficient income in order to reduce poverty (ESCAP, 2006:15; Fields, 1990:68; Gërxhani, 2004:268).

Barriers that push many of the unemployed into these lower-tier activities include relatively high start-up capital, labour relations issues, and the lack of basic financial-literacy skills. These barriers also prevent many from moving from the lower- to higher-tier activities in the informal economy (Fields, 1990:66; Günther & Launov, 2012:89; Wills, 2009:2). Such entry barriers also play a role in keeping the informal economy in South Africa relatively small in comparison with that of other developing countries (Heintz & Posel, 2008:27).

Previous research on waste pickers in South Africa focused mainly on the socio-economic position of waste pickers on dump sites (Chvatal, 2010; Samson, 2010; Theron, 2010). Samson (2010) found 19 studies conducted in South Africa on this subject, only five of which dealt with the street-waste pickers in different cities. Research on street-waste pickers in South Africa has, therefore, been confined to small-scale case studies (Langenhoven & Dyssel, 2007; McLean, 2000). Furthermore, the focus of previous research on the various barriers experienced by street-waste pickers was limited. Also, prior to the present study, no countrywide analysis of street-waste pickers had been conducted. We have attempted to fill this particular gap in the literature on both counts.

The aim of this research is to explore the nature of the barriers that may prevent street-waste pickers in South Africa from improving their socio-economic conditions.

We identified human-capital constraints, labour market characteristics, limited earning potential, and social aspects as possible barriers. The education levels of street-waste pickers, their language proficiency, as well as their previous full-time job experience were examined so as to explore the possible human-capital and labour market barriers. These are all aspects that may influence the street-waste pickers' likelihood of finding employment in the higher tier of the informal economy or in the formal labour market. The income earned by street-waste pickers was also analysed to determine whether it provides them with an opportunity to improve their socioeconomic conditions. The social background and conditions of street-waste pickers were investigated to observe the extent to which these serve as social barriers, preventing them from integrating and being part of the larger community in which they live.

The analysis presented in this paper is based on data collected from a sample of 914 street-waste pickers in South Africa, using a mixed-method research approach. The results of the research follow the discussion of the literature and research methodology presented in the next sections.

2 Literature review

The concept of the informal economy gained recognition in the literature with the seminal paper of Hart (1973). Various theoretical approaches have been used to study the informal economy since then. The Dualist Theory postulates that the informal economy can absorb the growing number of people who cannot find economic opportunities in the more productive and remunerative formal economy (Heintz & Jardine, 1998:32).

The informal economy features unregistered or unofficial small-scale or even subsistence enterprises, temporary employment and self-employed persons (Becker, 2004:13; Hart, 1973:68). Table 1 gives an overview, derived from the literature, of the characteristics of these subsistence and unofficial enterprises.

The subsistence enterprises or activities in the informal economy are also referred to as "lower-tier, informal-economy activities" (Fields, 1990:69). Activities in the lower tier are often characterised by low productivity, by income-earning opportunities that yield low wages, and by irregular working hours (Becker, 2004:13). There is agreement in the literature that income in the informal economy tends to decline as one moves closer to the subsistence or lower-tier activities (Wills, 2009:1).

Lower-tier activities are often the ones with few barriers, or even unrestricted entry (Fields, 1990:69). Waste picking also falls into this category. Waste picking as a subsistence activity is labour-intensive, requires no capital or start-up costs, no education or skills are needed, and the waste picker has a guaranteed buyer for the waste picked. The only requirements for the waste picker are the physical ability to pick waste, access to waste, and access to a buyer of waste - whether a buy-back centre (BBC)3, craftsmen, middlemen or informal waste collectors with their own transport, also referred to as "hawkers" (Viljoen, Schenck & Blaauw, 2012:21; Viljoen, 2014).

The low entry requirements make waste picking a feasible income-generating opportunity for the very poor and economically disadvantaged to earn cash income (Masocha, 2006:843). Street-waste picking is one of the means of subsistence for the poor who have no other income-generating options available to them (Carrasco, 2009:17; Ullah, 2008:10). Waste picking serves as a survivalist strategy, safety net and temporary substitute for social protection (Losby, Else, Kmgslow, Edgcomb, Malm & Kao, 2002:9).

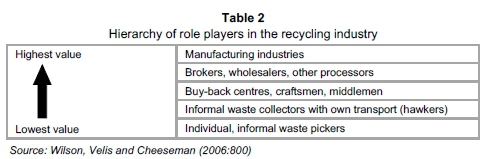

As a source of raw materials, these activities are also at the bottom end of the recycling industry's hierarchy (Ullah, 2008:2). The hierarchy of the role players in the recycling industry is illustrated in Table 2.

The level at which the informal recycling activities occur has an influence on the income earned, the working conditions, and the social status of the participants. People active at the lower end of the hierarchy are less organised, lack support networks, and add less value to the waste they collect. These influences increase their vulnerability to exploitation, which is reflected in the low incomes they earn (Wilson et al, 2006:801). Despite their contribution to the recycling of waste products, which benefits the community at large, the social and economic circumstances of street-waste pickers keep them on the margins of poverty.

According to the Sustainable Livelihood Approach, any person needs the capabilities to reap the benefits from economic opportunities in order to reduce their poverty and to provide them with economic security and social well-being (Krantz, 2001:10-11). These capabilities do not only entail the ability to earn an income, but also the capacity to consume and to earn assets. Authors such as Adato and Meinzen-Dick (2002:6), and Krantz (2001:10-11), categorise the main types of assets or capital as human, financial, natural and social capital, as well as access to information. A lack of capabilities will constrain the poor from seizing any opportunities that may lift them out of poverty.

Low levels of education, deficient language proficiency, and little previous experience in the formal economy may limit street-waste pickers' labour market mobility. As a result, it can be difficult for them to move away from the marginalised and lower-tier activities of the informal economy to higher-tier, informal or formal labour markets (Viljoen, 2014). The existence of social barriers may prevent street-waste pickers from acquiring social capital that will enable them to become part of the community, to be integrated into society, and to form part of the larger group. These barriers can also deprive them of the ability to build the trust and relationships needed to function efficiently (Adato & Meinzen-Dick, 2002:6; Krantz, 2001:10-11).

To improve their position, they need to move upwards in the hierarchy (Wilson et al., 2006:800), within the recycling industry, to other higher-tier, informal-economy activities or to the formal economy. A synthesis of the available literature suggests that, in low-tier activities such as waste picking, the informal economy offers its participants little opportunity to invest in human capital in order to increase their skills level. The implication is that, once in the informal economy, their chances of moving up the ladder are constantly diminishing (Suharto, 2002:116).

The literature on street-waste pickers in South Africa does not focus on the barriers that prevent them from improving their socio-economic conditions. This paper therefore reports on research conducted to fill this gap. Survey research among the waste pickers themselves is the only feasible option for achieving the research objective. The following sections describe the research methodology and present the results and analysis.

3 Research methodology: Survey of street-waste pickers in South Africa

3.1 Research type and strategy

In an ideal world, the research methodology would have required, at a minimum, data over two time periods, that is, panel data in order to determine if certain characteristics are correlated with the probability of transitioning into a hypothetical, improved socio-economic position. Given the fluid nature of this activity and the ethical requirement of anonymity, panel data is not a viable option. As an alternative, one would need some kind of comparison group to allow one to ascertain if certain identified characteristics are correlated with the probability of being a street-waste picker rather than doing anything else. The issue, however, is that the majority of street-waste pickers have not chosen this as a preferred occupation, but see it as a second-best alternative to formal employment.

Street-waste pickers are regarded as an "unknown population" and as a "hard-to-reach" research population in terms of their numbers and the difficulty of finding them owing to the nature of their work (Viljoen, 2014). These characteristics, coupled with the flexibility needed to accommodate the holistic nature of the research objectives, provided the rationale for using a mixed-method approach for this research. The mixed-method approach was used to mix quantitative and qualitative data in the collection and analysis stages in a single study (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2011:5). The results of the qualitative questions support the quantitative data and reflect the voice of the street-waste pickers.

Primary data were collected in two phases using a survey design in each phase. In the first phase, quantitative and qualitative data were collected concurrently from BBCs. The rationale for including the BBCs in the research was to obtain a more complete understanding of the street-waste pickers, of their activities in the recycling industry, and of factors that affect their socioeconomic conditions. Without the BBCs, the average waste picker cannot operate. The best places to find the street-waste pickers were at the BBCs where the street-waste pickers sell the waste that they have collected (Schenck & Blaauw, 2011a:419). Thus, data on the best place and best time to find the street-waste pickers were also collected from the BBCs. The data and information obtained from this data set informed the procedures that were to be followed in collecting data from the street-waste pickers. In the second phase, quantitative and qualitative data were collected concurrently from the street-waste pickers.

The quantitative and qualitative data sets obtained in both phases of the study were analysed separately and were integrated in the reporting and interpretation stage. The integration of these two data sets, coupled with the integration of the data and information obtained from the literature review and theoretical overview in the reporting and interpretation stage, enhanced the reliability of this study.

3.2 Survey instrument

A face-to-face survey approach was used to collect data and information on the socio-economic conditions of the street-waste pickers. Face-to-face surveys can be used effectively when members of the research population have limited literacy levels, such as is the case with street-waste pickers (Babbie & Mouton, 2011:249).

The survey instrument used by Schenck and Blaauw (2011a) formed the foundation for the design of the structured qualitative and quantitative questionnaire to be used for the collection of the data. Advice and input from Melanie Samson, an expert on research among women in the informal economy and on waste pickers in South Africa, as well as the input and advice of a statistician, were incorporated in the final version. The revised questionnaire was pilot-tested by the research team during their visits to the BBCs in the reconnaissance phase.

Owing to the lack of research on BBCs, a completely new questionnaire had to be designed to collect data from them. A thorough review of the existing literature on waste pickers and the limited information available on BBCs served as a starting point and informed the type of questions to be included in the questionnaire. To help shape the final questionnaires and to ensure the validity and adequacy of the research instruments, a pilot version of the two questionnaires was administered among street-waste pickers as well as among two BBC owners.

3.3 Sampling method

Street-waste picking is not officially recognised as an occupation and only estimates on the total number of street-waste pickers in South Africa are available. Some street-waste pickers also do not have a fixed address and sleep on the street or in the bushes. During the day, they move around the cities to collect waste, depending on the availability thereof.

The recycling industry as a whole is largely under-researched and no central or reliable database on the location of BBCs could be found. The research team visited all the envisaged cities in a recognisance effort to locate and visit all the BBCs. The BBCs were also not able to provide reliable estimates on the number of street-waste pickers who sell their waste to them owing to the nature of the street-waste pickers' visits to the BBCs. The street-waste pickers visit the BBCs at different times of the day and on different days of the week. In some cases, they visit the same BBC more than once on a particular day, or they visit more than one BBC on the same day.

Because no sampling frame is available for this research population, a non-probability sampling technique was used, as suggested by Bhattacherjee (2012:70), to collect data from both the BBCs and the street-waste pickers. The non-probability sampling technique used was snowball sampling, which is a respondent-assisted sampling method. All ethical considerations were strictly adhered to and ethical clearance was obtained before the research commenced.

3.4 Data collection

The results of the study are based on data collected from 914 street-waste pickers and 69 BBCs (excluding scrap-metal dealers) in 13 cities across all provinces in South Africa. The cities included all the provincial capitals as well as other important economic centres in each province. The data were collected between 19 April 2011 and 28 June 2012.

The next section provides insights into the human-capital, labour market, economic and social barriers that make it difficult for street-waste pickers to improve their socio-economic conditions.

4 Analysis and interpretation of results

4.1 Human-capital and labour market barriers

High levels of unemployment as well as structural changes in the form of lower demand for semiskilled and unskilled workers force many people in South Africa into the informal economy (Carrasco, 2009:17). Institutional failure is, however, not the only reason why street-waste pickers are unable to move upwards in the hierarchy of informal-economy activities. Certain inherent characteristics may also contribute to their inability to find employment in the formal or informal economy. These individualities relate to the street-waste pickers' level of human-capital development, which includes their highest education levels, language proficiency, and previous full-time work experience.

There are few job prospects for uneducated people (Fryer & Hepburn, 2010:6). An analysis of their educational levels reveals that only three street-waste pickers were on a level higher than Grade 12. An overwhelming majority (92.9 per cent) of the street-waste pickers had not completed their formal schooling. Only 44 per cent had some secondary schooling, with 48.5 per cent having more limited schooling or no schooling at all (see Figure 1).

The age groups 35-44 years and 45-54 years contained the largest proportions of street-waste pickers without any formal schooling, namely 19 per cent and 17 per cent, respectively (see Table 3).

Youth street-waste pickers between 14 and 34 years of age (the broad definition) had the highest school-attainment levels. They also constituted the age group within which the highest percentage of street-waste pickers had completed their secondary schooling. The high percentage of young people involved in waste picking is a reflection of the employment crisis, which takes a heavy toll on the youth in South Africa in general. Having completed secondary schooling is indeed no "meal ticket", but merely a "hunting licence", with no guarantee of finding a job. Low education levels make it even more difficult for the young street-waste pickers to compete for jobs.

The reasons why so many of the street-waste pickers left school early provide a qualitative perspective on their inability to acquire higher levels of human capital. Not completing school constitutes an important barrier in terms of future labour market involvement and limits the current and future accumulation of human capital that is important in order to compete in a labour market characterised by decreasing demand for unskilled labour.

The respondents were therefore asked in an open-ended qualitative question about the reasons why they had not been able to complete their schooling. Seven themes were identified. The majority (68 per cent) of the street-waste pickers left school early owing to financial difficulties, as indicated in Table 4.

Of concern is the fact that 17.9 per cent of those who left school because of poverty or financial problems had lost one parent, or both parents, and had no one to care for them. Poverty has a detrimental effect on the capability of an individual to obtain benefits from schooling (Fryer & Hepburn, 2010:6).

Reasons other than those of a financial nature that made young people leave school early included family-related issues, problems at school, behavioural issues, health, and age. Family-related issues were the second-most common reason for leaving school early (see Table 5).

When people are excluded from school, regardless of the reason, they are deprived of the literacy and numeracy skills that can be attained as a result of formal schooling (Berntson, 2008:26).

Without the basic skills mentioned above, it becomes difficult to find employment, whether in the formal or informal labour market, and any inability to properly communicate exacerbates the situation. The self-perceived language proficiency of the respondents shows that the majority (53.7 per cent) of the street-waste pickers could not understand English well and 56 per cent could not speak English well. The same trend was observed with Afrikaans, where 51.8 per cent of the street-waste pickers were not able to understand Afrikaans, and 53.7 per cent could not speak Afrikaans well (see Figure 2).

A comparison between language proficiency and age revealed that the majority of the street-waste pickers who could speak and understand English and Afrikaans well were in the older age categories (between 35 and 54 years). Table 6 shows that the largest percentage of street-waste pickers who could not speak and understand Afrikaans, English, or both, was in the youngest age categories, namely 14-24 years and 25-34 years.

The results could be an overestimation of street-waste pickers who were proficient in English and Afrikaans, because language proficiency was not evaluated and the self-assessment merely reflected the street-waste pickers' own perception of their level of proficiency. Notwithstanding this, it was clear that a lack of language proficiency can constitute a barrier for a third of the street-waste pickers in their possible attempts to find alternative employment.

This finding correlates well with the low levels of educational attainment, where only 24.5 per cent of the young street-waste pickers (14-34 years) had completed their secondary schooling. The implication is that younger street-waste pickers may find it even more difficult to compete for possible formal employment opportunities where language proficiency is critical, especially against the backdrop of an oversupply of unschooled labour in South Africa.

The level of human-capital development in terms of school-attainment levels, work experience, skills, and language proficiency are barriers that make it difficult for the street-waste pickers to find formal employment or more highly paid informal jobs. Consequently, their ability to improve their socio-economic conditions diminishes. According to standard labour market theory, education and training are two important factors of human-capital development and can improve a person's earnings (Berntson, 2008:26). High levels of human capital also enable people to initiate and use other productive assets (Adato & Meinzen-Dick, 2002:6; Krantz, 2001:10-11).

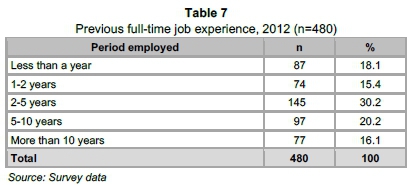

The lack of human-capital development and the effect thereof on the employability of the street-waste pickers are reflected in the analysis of their previous full-time work experience. Just more than half (52.4 per cent) of the street-waste pickers previously had a full-time job with benefits.4 These street-waste pickers also tend to be those with relatively better levels of education.5 Almost half of the respondents therefore lacked full-time work experience, which could also make them more vulnerable in the competition to find and get a full-time job. The majority of the street-waste pickers who previously had full-time jobs also did not have them for long periods of time, as indicated in Table 7.

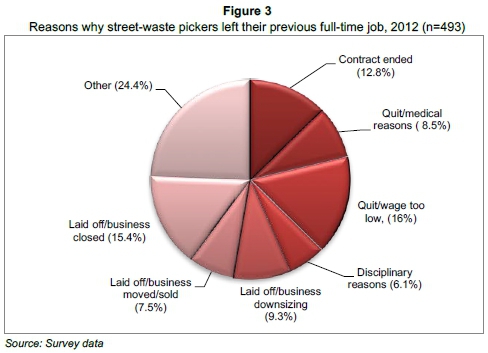

The street-waste pickers who had held their previous full-time work for longer periods were the older street-waste pickers who only picked waste to supplement their pension or old-age grants. The reasons they gave for leaving their last full-time work are presented in Figure 3 and relates to disciplinary actions, quitting of jobs, lay-offs and other reasons.

The responses to a qualitative question on whether the street-waste pickers were looking for, and would like to have a full-time job revealed that 85.7 per cent of the street-waste pickers were indeed looking for another job. More than a third (345) of the street-waste pickers indicated that they would take any job they could get. To them, street-waste picking was just a survival activity. Most street-waste pickers would have preferred to have full-time employment, as indicated by the excerpts that follow:

"I would rather have a decent job. "

"I want to find a job. "

"Not a good way of making a living. "

"I just want a good job. "

The responses of the street-waste pickers also implied that street-waste picking does not yield high levels of income. Low income can possibly constitute an economic barrier preventing street-waste pickers from improving their socio-economic conditions.

4.2 Income-earning opportunities as an economic barrier

The analysis of the income of street-waste pickers shows that their income was earned either on the day on which they had collected their waste or on a weekly basis. Most of the street-waste pickers (751 or 82 per cent) earned their income for a day's waste collected. Half of these street-waste pickers earned an income of R50 or below on a usual day. Another 25 per cent earned an income of between R51 and R85 on a usual day. The average income on a usual day was only R67.26, showing that the majority of street-waste pickers earned low incomes. The average income received for a usual week was R505.06, with half of the street-waste pickers getting only R300.

The global poverty measure of USD2.50 per day for a high middle-income country such as South Africa, discounted at the purchasing power parity exchange rate in 2012 of R5.69 (1RS, 2013:1), amounted to R14.23 per person per day. The USD2.50 per day poverty line represents the income necessary for one person, and not a whole household, to survive (McLean, 2000:20). On average, a street-waste picker had to support three people (excluding themselves). Therefore, the nominal income necessary for four persons amounted to R56.90, which is more than the median usual day income earned by the street-waste pickers. The income needed to support four people for a week in 2012 amounted to R398.30, which is also higher than the usual week median income of R300. The majority of the street-waste pickers therefore earned an income below the poverty line (see Figure 4).

The uncertainly about the street-waste pickers' income is another aspect that makes it difficult for them to improve their socio-economic conditions (Viljoen, 2014). The street-waste pickers' income differs from day to day. On some days, they might earn high incomes, and, on other days, they might earn low incomes, as reflected by the mean and median incomes received on a good and bad day or week as shown in Figure 4. It seems as if the street-waste pickers cannot be certain of the income they will be earning by collecting waste on any given day or in any particular week.

There were significant differences in the incomes earned on a usual, good and bad day and in a usual, good and bad week. Factors that influence the income are the type and value of the recyclable waste products available, the location (e.g. residential or business) where the waste is picked, the weather, the demand and supply of recyclable waste, the fluctuating prices received for recyclable waste products, the level of competition for recyclable waste products, and the type of equipment used to carry the waste (Viljoen, 2014). Exogenous factors such as the behaviour of people in the other "sectors" of the waste-producing and waste-removal "system", industrial action, and unforeseen holiday periods also play a role in this regard.

The street-waste pickers' low and uncertain income levels and their resultant inability to meet their basic needs were a real concern for them, as shown by their comments on this issue:

"The uncertainty of my income worries me. "

"Sometimes you don't make enough to buy food. "

The expenditure patterns of street-waste pickers showed that food was the major consumable item purchased. This comes as no surprise. Sen (1999) points out that, because their earnings are so low, the income of marginalised people such as waste pickers is mostly spent on food, that is, for survival purposes. The second-most products bought were cleaning materials and cigarettes, tobacco, snuff, or other items for smoking. Fewer street-waste pickers bought clothes, shoes and blankets (some of these items were salvaged from the waste they collected), or paid for transport and sources of energy. Only 26.2 per cent paid for the place where they slept and a mere 4.2 per cent incurred medical expenses. A large percentage (41.6 per cent) of the street-waste pickers also spent some of their money on alcoholic beverages such as beer, wine and spirits. These behavioural patterns are analogous with research findings that show that poor people spend a larger portion of their incomes on alcohol and tobacco than do richer people (Gangopadhyay & Wadhwa, 2004). Very few (4.7 per cent) paid school/college fees and only 4.2 per cent made contributions to a stokvel or burial society. Again, the literature confirms the inability of the poor to exercise consumption choices with potential future benefits (Banerjee & Duflo, 2007).

The income earned by the street-waste pickers was not enough to enable them to participate fully in their community. This finding echoes Furedy's (1990:10) observation that street-waste pickers are also inhibited by social barriers from translating their earnings into improved standards of living.

4.3 Social barriers

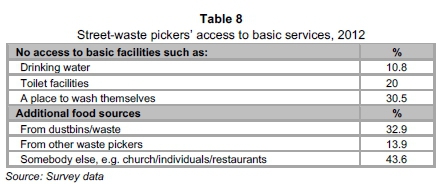

Indicators that contextualise the social conditions of street-waste pickers are access to resources that meet their basic human needs (like the type of structure or shelter where they usually sleep), access to food, and access to, or the availability of, other basic household services. A lack of means to fulfil these social needs inhibits the street-waste pickers' capability to be productive.

Figure 5 illustrates the type of structure or shelter where the street-waste pickers usually sleep.

The lack of proper housing and of a place to store their collected waste are serious problems among street-waste pickers. The street-waste pickers who slept on the street or in the veld or bush also lacked access to other basic household services such as drinking water, toilet facilities, cooking facilities and washing facilities. As one of the street-waste pickers put it:

"My concern is a place to live and a place to bath ... ."

Table 8 illustrates the situation.

The street-waste pickers expressed their gratitude for the food that they received. One of them said:

"I am thankful to all the people who bring food to us after hours. "

The above findings confirm that street-waste pickers are generally deprived of the social capital needed to become part of the community.

The reasons given by respondents for becoming street-waste pickers also show that these people are indeed marginalised. The single-most important reason given by 36.4 per cent of the street-waste pickers for becoming such pickers was that they had no other option. Another 14 per cent also said that they were doing the job because they could not find work. For 19.4 per cent, the motive for becoming street-waste pickers was to earn some income, and some indicated that they picked waste just to be able to buy food.

The human capital, labour market, and social barriers are interdependent and are collectively responsible for keeping street-waste pickers in the lower levels of the informal economy, with little hope of improving their socio-economic conditions.

5 Conclusion

High levels of unemployment and structural changes in the South African economy are forcing scores of low-skilled and unskilled people into the lower tiers of the informal economy. Collecting and selling recyclable waste is one of the activities people resort to in an effort to earn an income in the informal economy. Existing research on the activities and lives of waste pickers mostly focuses on the waste pickers working on municipal-dump sites and generally takes the form of small-scale case studies. Research on the obstacles facing the street-waste pickers is limited. Consequently, the aim of the research reported in this paper was to fill the gap by investigating the barriers standing in the way of the street-waste pickers improving their socio-economic situation. The barriers in question relate to the street-waste pickers' lack of human capital, labour market immobility, income earned, and the acquisition of social capital. A mixed-method research approach was used. A countrywide survey of 914 street-waste pickers and 69 BBCs in all nine provinces of South Africa formed the foundation of the analysis.

Deprived social and economic backgrounds played a significant role in preventing the majority of the street-waste pickers from completing their formal schooling. Their low levels of education, limited language proficiency, and lack of formal work experience impacts negatively on their labour market mobility and on their ability to compete for jobs.

The street-waste pickers face an economic barrier in the form of low and uncertain income earned. All the income variables analysed suggested that, given the number of their dependants, most street-waste pickers found themselves below the global poverty line appropriate for a high middle-income country like South Africa. Any form of planning for the future or attempts to improve their socio-economic situation therefore become extremely difficult if not impossible. From a social perspective, the prospects of improving their socio-economic conditions are also limited. Lack of proper housing, lack of access to basic services, and, in some instances, lack of food constitute a social barrier that seems almost insurmountable. Most street-waste pickers are caught in a poverty trap from which it is difficult to escape.

The human-capital, labour market, economic and social barriers are therefore dualistic in nature, as they do not only contribute to the street-waste pickers' poor socio-economic conditions, but may also keep them trapped in the lower tier of the informal economy. Interventions to address these barriers are needed in order to enable street-waste pickers to improve their position.

Any policy interventions will therefore have to address, almost simultaneously, the poverty, human-capital, economic, social and labour market barriers that make it inherently difficult for street-waste pickers to improve their socio-economic conditions. Interventions aimed at supporting street-waste pickers should not deprive them of their livelihood, meagre as it is. A blanket-type strategy is bound to fail.

The only feasible approach to achieve this awareness is to conduct in-depth studies at a microlevel into the social and economic lives of street-waste pickers. If this can be coupled with the use of a longitudinal approach and/or comparison group, it will contribute to an improved understanding of the topic at hand.

The research process was subject to the same limitations as experienced in all cross-sectional studies. Issues such as endogeneity make inferences in terms of causality difficult. However, the research reported on in this paper lays a suitable foundation for focused research initiatives in all towns and cities in South Africa. Waste pickers in South Africa share the same tribulations as those in Columbia. Pushing their trolleys, collecting their waste, and selling constitute the only alternative for many of South Africa's citizens. Indeed, they cannot afford to become any poorer.

References

ADATO, M. & MEINZEN-DICK, R. 2002. Assessing the impact of agricultural research on poverty using the sustainable livelihoods framework. Food, Consumption and Nutrition Division (FCND), Discussion paper number 128. [ Links ]

BABBIE, E. & MOUTON, J. 2011. The practice of social research. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

BALLVE, T. 2008. Waste picker: 21st century profession. Available at: http://newamericamedia.org/news/view [accessed May 2010]. [ Links ]

BANERJEE, A.V. & DUFLO, E. 2007. The economic lives of the poor. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1):141-167. [ Links ]

BECKER, K.F. 2004. The informal economy: Fact finding study. Valhallavagen, Stockholm: Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). [ Links ]

BERNTSON, E. 2008. Employability perceptions. Nature, determinants, and implications for health and well-being. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Stockholm University, Sweden. [ Links ]

BHATTACHERJEE, A. 2012. Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices. USF Open Access Textbooks Collection, Book 3. Available at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/oa_textbooks73 [accessed January 2013]. [ Links ]

CARRASCO, C.H. 2009. Waste pickers, scavengers or catadores: Conceptualizing "Asmare" as a comprehensive and health promoting community initiative in Brazil. Available at: http://www.bestpractices-healthpromotion.com/attachments/File/best-practices/Exemplary%20students%20papers/Christine_Carrasco_Assignment_1_resubmission_feedback.pdf [accessed March 2012]. [ Links ]

CHEN, M.A. 2012. The informal economy: Definitions, theories and policies. WIEGO working paper number 1, Women in Informal Employment, Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO). USA: Cambridge. [ Links ]

CHVATAL, J. 2010. A study of waste management policy implications for landfill waste salvagers in the Western Cape. Unpublished MA dissertation, University of Cape Town, South Africa. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. & PLANO-CLARK, V.L. 2011. Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.) Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

DJANKOV, S., LIEBERMAN, I., MUKHERJEE, J. & NENOVA, T. 2002. Going informal: Benefits and costs. Available at: http://www_csd_bg_news_bert_nenova_pdf [accessed February 2013]. [ Links ]

ESCAP (ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC). 2006. Poverty and the informal sector. Committee on Poverty Reduction, 29 November - 1 December 2006, Bangkok, United Nations Economic and Social Council. Available at: http://www.unescap.org/pdd/CPR/CPR2006/English/CPR3_1E.pdf [accessed March 2011]. [ Links ]

FIELDS, G.S. 1990. Labour market modelling and the urban informal sector: Theory and evidence. In: Turnham, D. & Salome, B. (eds.) The informal sector revisited. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). [ Links ]

FRYER, D. & HEPBURN, B. 2010. It's jobs, stupid! Social exclusion, education, and the informal sector in Grahamstown, Fort Beaufort and Duncan Village. Institute of Social and Economic Research, Rhodes University, Working paper series number 5. [ Links ]

FUREDY, C. 1990. Social aspects of solid waste recovery in Asian cities. Environmental Sanitation Reviews, 30(1):1-51. [ Links ]

GANGOPADHYAY, S. & WADHWA, W. 2004. Changing pattern of household consumption expenditure. New Delhi: Society for Economic Research & Financial Analysis. [ Links ]

GËRXHANI, K. 2004. The informal sector in developed and less developed countries: A literature survey. Public Choice, 120(3/4):267-300. [ Links ]

GÜNTHER, I. & LAUNOV, A. 2012. Informal employment in developing countries - opportunity or last resort? Journal of Development Economics, 97(1):88-98. [ Links ]

HART, K. 1973. Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 11(1):61-89. [ Links ]

HAYAMI, Y., DIKSHIT, A.K. & MISHRA, S.N. 2006. Waste pickers and collectors in Delhi: Poverty and environment in an urban informal sector. Journal of Development Studies, 42(1):41-69. [ Links ]

HEINTZ, J. & JARDINE, J. 1998. Poverty and economics in South Africa. National Labour and Economic Development Institute (NALEDI), Gauteng, South Africa, Briefing paper - occasional publications series number 3. [ Links ]

HEINTZ, J. & POSEL, D. 2008. Revisiting informal employment and segmentation in the South African labour market. South African Journal of Economics, 76(1):26-44. [ Links ]

HOUSE, W.J., GERRISHON K.I. & McCORMICK, D. 1993. Urban self-employment in Kenya: Panacea or viable strategy? World Development, 21(7):1205-1223. [ Links ]

IRS (INTERNAL REVENUE SERVICE). 2013. Yearly average currency exchange rates: Translating foreign currency into U.S. dollars. Available at: http://www.irs.gov/Individuals/International-Taxpayers/Yearly-Average-Currency-Exchange-Rates [accessed August 2013]. [ Links ]

KRANTZ, L. 2001. The sustainable livelihood approach to poverty reduction: An introduction. Valhallavagen, Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). [ Links ]

LANGENHOVEN, B. & DYSSEL, M. 2007. The recycling industry and subsistence waste collectors: A case study of Mitchell's Plain. Urban Forum, 18(1):114-132. [ Links ]

LAUNOV, A. & GÜNTHER, I. 2006. Competitive and segmented informal labor markets. Proceedings of the German Development Economics Conference, Berlin 2006/Verein für Socialpolitik, Research Committee Development Economics, Number 16. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/19843 [accessed October 2013]. [ Links ]

LEHMANN, H. & PIGNATTI, N. 2007. Informal employment relationships and labor market segmentation in transition economies: Evidence from Ukraine, Discussion paper no. 3269, Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). [ Links ]

LOSBY, J.L., ELSE, J.F., KINGSLOW, M.E., EDGCOMB, E.L., MALM, E.T. & KAO, V. 2002. Informal economy literature review. The Aspen Institute/FIELD, Washington, D.C. Available at: http://www.fieldus.org/li/pdf/InformalEconomy [accessed June 2012]. [ Links ]

MALONEY, W.F. 2004. Informality revisited. World Development, 32(7):1159-1178. [ Links ]

MASOCHA, M. 2006. Informal waste harvesting in Victoria Falls town, Zimbabwe: Socio-economic benefits. Habitat International, 30(4):838-848. [ Links ]

MCLEAN, M. 2000. Informal collection: A matter of survival amongst the urban vulnerable. Africanus, 30(2):8-26. [ Links ]

SAMSON, M. 2010. Reclaiming reusable and recyclable materials in Africa: A critical review of English literature. Johannesburg: WIEGO. [ Links ]

SCHENCK, C.J. & BLAAUW, P.F. 2011a. Living on what others throw away: An exploration of the socioeconomic circumstances of people selling recyclable waste. The Social Work Practitioner Researcher, 23(2):135-153. [ Links ]

SCHENCK, R. & BLAAUW, P.F. 2011b. The work and lives of street waste pickers in Pretoria - a case study of recycling in South Africa's urban informal economy. Urban Forum, 22(4):411-430. [ Links ]

SEN, A. 1999. Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

SUHARTO, E. 2002. Human development and the urban informal sector in Bandung, Indonesia: The poverty issue. New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, 4(2):115-133. [ Links ]

THERON, J. 2010. Options for organising waste pickers in South Africa. Available at: http://www.wiego.org/publications/Orgamzing_Waste_Pickers_S_Africa.pdf [accessed April 2012]. [ Links ]

ULLAH, M.S. 2008. Self-employed proletarians in an informal economy: The case of waste pickers of Dhaka city. Available at: http://excludedvoices.wordpress.com/2010/08/21/self-employed-proletarians-in-an-informal-economy-the-case-of-waste-pickers-of-dhaka-city/ [accessed January 2011]. [ Links ]

VILJOEN, J.M.M. 2014. Economic and social aspects of street waste pickers in South Africa. Unpublished PhD (Economics), University of Johannesburg. Available at: https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za/ [accessed December 2014]. [ Links ]

VILJOEN, J.M.M., SCHENCK, C.J. & BLAAUW, P.F. 2012. The role and linkages of buy-back centres in the recycling industry: Pretoria and Bloemfontein. Acta Commercii, 12(1):1-12. [ Links ]

WILLS, G. 2009. South Africa's informal economy: A statistical profile. Women in informal employment, globalizing and organizing (WIEGO), Urban policies research report number. 7. Available at: http://www.inclusivecities.org/research/RR7_Wills.PDF [accessed November 2012]. [ Links ]

WILSON, D.C., VELIS, C. & CHEESEMAN, C. 2006. Role of informal sector recycling in waste management in developing countries. Habitat International, 30(4):797-808. [ Links ]

Accepted: November 2015

1 The authors wish to thank the anonymous referees of Economic Research Southern Africa (ERSA) and of the South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences (SAJEMS) for their helpful comments on earlier versions of the paper. The authors also wish to acknowledge ERSA for financial assistance with this research. All errors and omissions remain our own.

2 Ease of entry into the lower-tier activities also differs. For small manufacturing industries, small retail stores, and backyard industries, the capital and start-up capital varies. The larger operations that require higher levels of skills need more startup capital than the smaller operations, which require lower-skilled labour (House, Gerrishon & McCormick, 1993:1213). The entry requirements for domestic workers, single street traders, day labourers and waste pickers also differ to some extent. See Viljoen (2014) for a detailed exposition of this aspect.

3 Viljoen et al. (2012) define BBCs as depots where waste collectors can sell their recyclable waste. Buy-back centres (BBCs) fulfil an important role in facilitating the recycling potential of waste pickers in the informal economy. The BBCs, in turn, sell these waste products to other larger BBCs or directly to recycling companies (Viljoen et al., 2012).

4 See Appendix 1 for a detailed exposition of the nature and types of jobs held by street-waste pickers on a full-time basis.

5 See Appendix 2 for the levels of education of street-waste pickers who had a full-time job previously.