Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versão On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.18 no.4 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2222-3436/2015/V18N4A11

ARTICLES

Relationship intention and satisfaction following service recovery: The mediating role of perceptions of service recovery in the cell phone industry

Liezl-Marié Kruger; Pierre Mostert; Leon Tielman de Beer

WorkWell: Research Unit for Economic and Management Sciences, North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus

ABSTRACT

In an industry characterised by fierce competition, cell phone network providers find it increasingly difficult to retain their customers after service failure. It is therefore essential for cell phone network providers to offer effective service recovery when they attempt to restore customer satisfaction following service failure. As it has been argued that relationships between customers and service providers should be considered a key determinant of the service recovery required to restore post-recovery attitudes and behavioural intentions, the purpose of this study was to determine the relationships between South African cell phone customers' relationship intentions, their perceptions of service recovery and their satisfaction following service recovery. Personal in-home interviews were conducted to collect data from 605 cell phone customers residing in the Johannesburg metropolitan area. In addition to the significant positive relationships found between cell phone users' relationship intentions, perceived service recovery and satisfaction after service recovery, this study found that perceived service recovery played a mediating role in the relationship between relationship intention and satisfaction following service recovery. The study concludes that, although a direct relationship exists between relationship intention and satisfaction following service recovery, perceived service recovery plays an additional indirect complementary role in this relationship. It is recommended that, in addition to focusing their relationship efforts on customers with relationship intentions, cell phone network providers also offer positively perceived service recovery to these customers, as this would lead to greater satisfaction following service recovery.

Key words: relationship intention, perceived service recovery, satisfaction after service recovery, service failure, service recovery, cell phone industry

1 Introduction

In a service environment where service failures are unavoidable and occur often (Bateson & Hoffman, 2011:352-353; Egan, 2011:149), service providers face the challenge of trying to maintain customer relationships by attempting to provide quality service delivery (Nikbin, Ismail, Marimuthu & Abu-Jarad, 2011:19; Tsarenko & Tojib, 2011:383, 391). Service providers' efforts first to avoid and then to recover from service failures become apparent when the possibly negative consequences of service failures were considered. These include customers displaying lingering anger, resentment and hostility, spreading negative word-of-mouth, complaining, switching to competitors or even retaliating in some way (Tsarenko & Tojib, 2011:382). Service providers therefore apply service recovery strategies when service failures occur by trying to restore customers' satisfaction (Huang, 2011:513; Robinson, Neeley & Williamson, 2011:96; Van Vaerenbergh, De Keyser & Larivière, 2014:47).

Previous research has considered a number of influences on customer satisfaction following service recovery, including perceived justice (Andreassen, 2000:165; McCullough, Berry & Yadav, 2000:132; Tax & Brown, 1998:87; Wen & Chi, 2013:319), expectations of service recovery (Andreassen, 2000:165) and the relationship between customers and the service provider (Holloway, Wang & Beatty, 2009:386; Mattila, 2004:144; Long-Tolbert & Gammoh, 2012:398).

It has been argued that the relationship between a customer and the service provider in particular should be considered a key determinant of the service recovery required to restore post-recovery attitudes and behavioural intentions (DeWitt & Brady, 2003:202-203; Forrester & Maute, 2001:10; Kaltcheva, Winsor & Parasuraman, 2013:526; Singh & Sirdeshmukh, 2000:163). This supports the view that service providers should focus their efforts on customers with relationship intentions, as their willingness to forgive the service provider when service failures occur is a reflection of the kind of behaviour that will sustain the relationship (Kumar, Bohling & Ladda, 2003:670).

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationships between customers' relationship intentions, their perceptions of service recovery and their satisfaction following service recovery in the South African cell phone industry. This industry was chosen for a number of reasons. First, despite South Africa being one of the fastest-growing cell phone users in the world (Mbendi, 2011; Rainbow Nation, 2011), the market is characterised by fierce competition, with estimates indicating that the available market for new customers is less than 20 per cent and is shrinking (Van Niekerk, 2012:101). Secondly, with the introduction of number portability, which enables customers to move relatively easily between network providers (Seo, Ranganathan & Babad, 2008:182, 195) in conjunction with cell phone network providers' inability to differentiate themselves (Haenlein & Kaplan, 2012:467), it is becoming increasingly difficult for cell phone network providers to retain their customers. Thirdly, although the core and peripheral services offered are usually under the cell phone service providers' control, service failures in this industry are common (Independent Communication Authority of South Africa, ICASA, 2012:28), which impacts negatively on customer retention (Robinson et al., 2011:90). Finally, even entering into contracts with customers does not ensure their retention by a cell phone network provider, as customers will be bound only for the length of time covered in the contractual agreement (Malhotra & Malhotra, 2013:21; Seo et al., 2008:194). This highlights the difficulty experienced by cell phone network providers in establishing switching barriers to block the attractiveness of competitors' alternatives or to reduce customers' intentions to switch (Chang, Tsai & Hsu, 2013:383).

This article is structured as follows: after reviewing the relevant literature, the authors set out the problem statement, the purpose, the hypotheses and the conceptual model formulated for the study. Next, the methodology to be followed is discussed, before the authors present the results, the discussion and the recommendations. The article concludes with a statement on the limitations of the study, together with recommendations for future research.

2 Literature review

2.1 Service failure

The term service failure refers to a situation where a service provider fails to meet customers' service needs and expectations (Tsai, Yang & Cheng, 2014:140). Over time, customers are sure to experience service failures in any service environment (Harrison-Walker, 2012:115; Tax & Brown, 1998:87), with the result that customers' expectations of service delivery are not met (Berry & Parasuraman, 1997:65; Komunda & Osarenkhoe, 2012:83). Yi and Lee (2005:8-9) established that customers consider a service failure relating to the core service, for example, the disconnection of their cell phone service, as a more serious problem than peripheral service failures, such as the unavailability of their caller identification.

A service failure can be classified as either an outcome failure or a process failure. Outcome failures refer to those failures relating to the core service offering, implying that the service provider is not offering the basic service required to perform the core service (Smith & Bolton, 2002:10; Smith, Bolton & Wagner, 1999:358). Process failures on the other hand refer to failures directly attributed to the actions of service employees while delivering the service (Smith & Bolton, 2002:10). While outcome service failures affect customers' economic resources, process service failures affect their social resources (Chan & Wan, 2008:88-89). Regardless of the type of service failure that customers experience, it is essential for service providers to rectify these failures by restoring and maintaining their customer relationships (Chang et al., 2013:377; Tax & Brown, 1998:87). Further, service failures impact negatively on long-term profitability (Robinson et al., 2011:90).

2.2 Service recovery

Service recovery refers to the steps service providers take after a service failure in an attempt to reverse customers' loss (Fang, Luo & Jiang, 2013:344; Kau & Loh, 2006:102). Offering satisfactory service recovery is important, as it initially relieves customers' sense of betrayal (Van Vaerenbergh et al., 2014:47). Secondly, it enables service providers to regain their customers' trust (Du, Fan & Feng, 2010:585).

Previous research considered customers' perception of justice (fairness) as the primary antecedent to their satisfaction following the service recovery efforts (McCullough et al., 2000:132; Smith et al., 1999:369; Tax & Brown, 1998:80-81; Tax, Brown & Chandrashekaran, 1998:72-73; Wen & Chi, 2013:319). Tax and Brown (1998:80-81) identified three dimensions influencing customer satisfaction with service recovery, namely, procedural justice, interactional justice and distributive justice. Procedural justice refers to the perceived fairness of the process and the provider's policies for dealing with service failures. Interactional justice considers the perceived fairness of the way in which the customer is treated during the service recovery, and distributive justice involves the perceived fairness of the outcome of the service recovery (Mattila, 2001:584).

Service recovery strategies can be either tangible or intangible. Tangible service recovery, which usually takes the form of compensation of some kind, is used in an attempt to compensate customers for the service failure (Bateson & Hoffman, 2011:368-369). Compensatory recovery typically includes offering customers discounts, free merchandise, refunds, coupons and other economic incentives in an effort to counteract the inequity caused by a service failure (Fang et al., 2013:343; Smith et al., 1999:359). Although service providers may think that customers have to be compensated following a service failure, research has established that service providers do not necessarily have to offer a refund following a service failure (Blodgett, Hill & Tax, 1997:202). Customer satisfaction after service recovery can, in fact, be restored by a simple apology or proactive response (Smith et al., 1999:369) or by offering an explanation giving adequate and truthful information about the service failure (Wang & Mattila, 2011:434). Fang et al. (2013:343) concur, finding that apologising and explaining the reason for a service failure may, in fact, be a more effective and appropriate service recovery strategy. However, Wirtz and Mattila (2004:161) suggest that both interactional and procedural justice are necessary for restoring customer satisfaction through service recovery in the absence of compensation. Seawright, Detienne, Bernhisel and Larson (2008:266) concur, arguing that combining service recovery strategies in the form of tangible compensation with communication (such as an apology or explanation) is the most effective way of achieving customer satisfaction after service recovery. However, it is important for service providers to realise that, whatever the service recovery strategy implemented, positively perceived service recovery is essential if customer satisfaction is to be restored (Bitner, 1990:79; Huang, 2011:513; Tax & Brown, 1998:87; Wen & Chi, 2013:320).

2.3 Customer satisfaction

For the purpose of this study, customer satisfaction can be defined as customers' positive perceptions after consuming a service (Bolton & Christopher, 2014:17; Oliver, 1980:460). Churchill and Surprenant (1982:491) advocate that, when studying customer satisfaction, the expectancy disconfirmation theory should be considered. According to this paradigm, customer expectations determine zones of tolerance for service delivery. This is conceived as the gap between customers' expectations of the level of service they would like to receive and the level of service they are willing to accept (Zeithaml, Berry & Parasuraman, 1993:6). Whenever customers' expectations of service delivery are not met, and service delivery falls outside their zones of tolerance, service failures occur (Berry & Parasuraman, 1997:65; Komunda & Osarenkhoe, 2012:83). The importance of ensuring customer satisfaction following service recovery becomes apparent with the realisation that this could foster greater trust in the service provider, lead to favourable brand attitudes, and positively influence customers' word-of-mouth (Fang et al., 2013:353; Wen & Chi, 2013:319), their loyalty, commitment and retention (Kau & Loh, 2006:108).

Customer satisfaction can be determined for a specific service encounter (i.e. transaction-specific satisfaction), or following a number of service encounters (i.e. cumulative satisfaction) (Bloemer & De Ruyter, 1999:318; Homburg & Giering, 2001:45; Yu & Dean, 2001:235). While transaction-specific satisfaction provides insight into a specific service encounter, cumulative satisfaction is a barometer of customers' satisfaction with a service provider's perceived past, current and future performance (Anderson, Fornell & Lehmann, 1994:54). Cumulative satisfaction therefore takes into account the (nonlinear) chronology of interactions between customers and service providers (Fournier & Mick, 1999:15). Regardless of the way in which customer satisfaction is determined, it should be noted that satisfying customers must be a priority for service providers, as satisfied customers have a higher lifetime value for the providers. This lifetime value takes the form of spreading positive word-of-mouth, cooperating with, and becoming relationship partners with their service providers (Dorai & Varshney, 2012:407). For this reason, customer satisfaction can be regarded as a prerequisite for entering into long-term relationships with customers (Kim, Ok & Canter, 2012:59), strengthening customer loyalty and retaining customers (Cant & Erdis, 2012:938).

2.4 Relationship intention

When considering relationship marketing from the customers' perspective, it becomes clear that the relationship they decide to form with their service providers may differ in respect of degree of temporality, intensity, commitment and affect (Zayer & Neier, 2011:100). While some customers see exchanges as transactions and therefore do not want to form a relationship with a service provider, others may become active partners in a relationship with a service provider (Beetles & Harris, 2010:353, 354; Hess, Story & Danes, 2011:22; Kumar et al., 2003:669; Petruzzellis, 2010:625). Relationship intention can be defined as a customer's intention to build a relationship with a service provider (Kumar et al., 2003:669). Service providers should therefore form relationships with those customers who wish to become active partners (i.e. customers showing relationship intention), as they are less expensive to serve, they spread positive word-of-mouth opinions and are willing to pay premium prices. This translates into increased profitability during the lifetime of the relationship (Kumar et al., 2003:673). Ha and Jang (2009:320) believe that, in addition to these benefits, customers with relationship intentions are unlikely to change their patronage behaviour, even where there is a service failure. Kumar et al. (2003:669) propose that five sub constructs should be considered when measuring customers' relationship intentions: involvement, expectations, fear of losing the relationship, feedback and forgiveness.

2.4.1 Involvement

Zaichowsky (1985:342) defined involvement as "the perceived relevance of an object to an individual based on inherent needs, values and interests". From the perspective of relationship intention, Kumar et al. (2003:670) think of customer involvement as the extent to which a customer engages in relationship activities without obligation or coercion. Accordingly, Kumar et al. (2003:670) believe that customers with relationship intentions are emotionally involved with their service providers. When customers take an interest in the service providers they support, they become involved as partners in the relationship (Solomon, 2005:26-28), which results in their identifying with the organisation (Kumar et al., 2003:670) and experiencing increased satisfaction with their decision to support a specific service provider (Dagger & David, 2012:450).

When experiencing a service failure, involved customers would probably want to be part of the service recovery solution (Varki & Wong, 2003:89). This can be attributed to customers usually being more emotionally involved in the service recovery than they would be in routine service delivery (Fang et al., 2013:342). Because these customers place greater value on the service providers' service recovery strategies than less involved customers do (Camra-Fierro, Melero-Polo & Sese, 2014:15), it is self-evident that service providers attempt to satisfy involved customers by means of service recovery strategies. They benefit from this, as involved customers not only provide suggestions for improving the services, but also recommend the service provider through positive word-of-mouth reports (Camra-Fierro et al., 2014:16).

2.4.2 Expectations

Expectations can be seen as the standard of service customers use as a yardstick for evaluating their perceived experiences, leading to satisfaction judgements (Oliver, 1980:460; Zeithaml et al., 1993:1). Expectations therefore reflect what customers hope service delivery will entail (Churchill & Suprenant, 1982:492; Kim et al., 2012:60-61). Kumar et al. (2003:670) argue that, by cherishing higher expectations of the service provider, customers show greater concern, and accordingly care more for the service provider. Customers with higher expectations are therefore believed to have higher levels of relationship intention (Kumar et al., 2003:670).

The role played by the relationships established between customers and service providers when forming expectations of service recovery is unclear because there are conflicting research results. While Kim et al. (2012:74) argue that customers in established relationships with service providers have higher expectations of service recovery, Hess, Ganesan and Klein (2003:140) found that, when they expect the relationship with the service provider to continue, customers lower their expectations of service recovery, which results in increased satisfaction following recovery. More research into the influence of customer relationships on customers' service recovery expectations is therefore needed.

2.4.3 Fear of relationship loss

Customers prefer to continue relationships with service providers on account of the benefits they reap from such relationships, including confidence, special treatment and social benefits (Gwinner, Gremler & Bitner, 1998:109-110). Confidence benefits depend on customers having faith in the service provider's trustworthiness, having fewer perceptions of anxiety and risk, and knowing what to expect (Gwinner et al., 1998:109-110). Offering confidence benefits is particularly valuable, as these are the most important relational benefits customers want to experience when building relationships with service providers (Gwinner et al., 1998:109-110). This becomes clear when considering that confidence benefits increase customers' relational response behaviour, such as word-of-mouth, satisfaction and loyalty (Kinard & Capella, 2006:365).

The special treatment benefits customers hope to gain from their organisational relationships include reduced prices or special services (Hennig-Thurau, Gwinner & Gremler, 2002:242). Finally, social benefits, such as recognition by employees and developing a friendship with a specific service provider through repeated satisfactory interactions over time (Gwinner et al., 1998:109-110), forge bonds between customers and service providers (Homburg, Giering & Menon, 2003:44; Liang & Wang, 2006:123; Spake & Megehee, 2010:316, 319-320).

Concern that they may lose the benefits they receive, and thus the relationship with service providers, distinguishes customers with high relationship intentions from those with low relationship intentions (Kumar et al., 2003:670).

2.4.4 Feedback

Obtaining feedback from customers is one of the most effective means by which service providers can gain insights relating to actual service delivery, service quality and customer satisfaction (Egan, 2011:131). Customer feedback is valuable to service providers, as it facilitates improvement in service provision (Caemmerer & Wilson, 2010:305; Egan, 2011:131). Further, customer feedback informs service providers about service failures, thereby providing the necessary opportunity for service recovery and preventing a recurrence of the specific service failure (Fang et al., 2013:342-343; Lin, Wang & Chang, 2011:529-530; Wirtz, Tambyah & Mattila, 2010:380). Although every customer can give service providers feedback, Kumar et al. (2003:670) believe that it is specifically those customers with relationship intentions who give both positive (such as expressing gratitude or compliments) and negative (i.e. complaints) feedback without expecting a return or a reward. This view is supported by Hedrick, Beverland and Minahan (2007:70) and Tsarenko and Tojib (2011:382), who explain that customers, instead of ending their relationship, provide feedback to service providers when expectations are not met in an attempt to restore the relationship.

2.4.5 Forgiveness

Customers' willingness to forgive service providers becomes evident only when they experience a service failure (Strelan & Covic, 2006:1077). Despite being used as a coping strategy when there is a service failure (Tsarenko & Tojib, 2011:381, 387), customers may be reluctant to forgive service providers, possibly fearing that forgiving a transgression reflects condoning the service provider's behaviour (Stone, 2002:78). Kumar et al. (2003:670) therefore contend that customers with relationship intentions ascribe more value to their relationships with service providers than to unmet expectations (i.e. service failures) and thus choose to forgive them. A number of researchers support this opinion. For example, Karremans and Aarts (2007:910) explain that forgiveness is more likely to take place when the offender is a partner in a close relationship, whereas Chung and Beverland (2006:98) found that forgiveness makes it easier to restore the relationship with an offending relationship partner rather than terminating it. In addition, when they cast off their negative feelings by forgiving their service providers, customers can pursue ways of restoring the relationship with the service provider (Hedrick et al., 2007:70; McCullough, Fincham & Tsang, 2003:540; Tsarenko & Tojib, 2011:382).

3 Problem statement, purpose, hypotheses and conceptual framework

According to the expectancy disconfirmation theory, customers' satisfaction with service delivery is determined by comparing their expectations with the disconfirmation experienced during actual service delivery (Churchill & Surprenant, 1982:491). When service providers fail to meet their customers' expectations during service delivery, service failures (negative disconfirmation) are experienced as a consequent unequal exchange. Service providers therefore attempt to restore customer satisfaction (Huang, 2011:513) by eliminating the perceived inequality by means of service recovery (Fang et al., 2013:344; Kau & Loh, 2006:102).

It has been argued that the relationships between customers and service providers should be considered a key determinant of service recovery, which is required if post-recovery attitudes and behavioural intentions are to be restored (DeWitt & Brady, 2003:202-203; Forrester & Maute, 2001:10; Kaltcheva et al., 2013:526; Singh & Sirdeshmukh, 2000:163). It has further been suggested that it is possible to ensure customer satisfaction by means of service recovery without compensation (Blodgett et al., 1997:202), seeing that customer satisfaction following service recovery can be restored by offering a simple apology or an explanation, and providing adequate and truthful information about the service failure (Fang et al., 2013:343; Smith et al., 1999:369; Wang & Mattila, 2011:434). This study will accordingly consider the influence of service recovery that excludes compensation on satisfaction following service recovery.

In summary, it is believed that customers' relationship intentions will result in behaviour that will uphold the relationship when service failures occur (Kumar et al., 2003:670) and that perceived service recovery will influence satisfaction following the service recovery (Bitner, 1990:79; Huang, 2011:513; Tax & Brown, 1998:87; Wen & Chi, 2013:320).

This research is important because, despite significant advances in service failure and recovery research, there are still considered to be gaps in the literature (DeWitt, Nguyen & Marshall, 2008:270). In particular, DeWitt et al. (2008:270) express the opinion that, by determining possible mediators in service failure and recovery research, service providers can better design and deliver service recovery strategies. This research will accordingly set out to determine the relationships between cell phone customers' relationship intentions, their perceptions of service recovery and their satisfaction following service recovery. The following alternative hypotheses were formulated to support the purpose of the study:

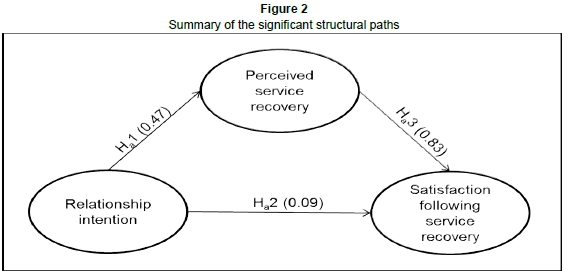

Ha1: There is a significant positive relationship between cell phone users' relationship intentions and perceived service recovery.

Ha2: There is a significant positive relationship between cell phone users' relationship intentions and their satisfaction following service recovery.

Ha3: There is a significant positive relationship between cell phone users' perceptions of service recovery and their satisfaction following service recovery.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between cell phone users' relationship intentions, perceived service recovery and satisfaction following service recovery.

4 Methodology

4.1 Research design, study population, data collection and sampling procedure

Like other studies which have investigated perceived service recovery and satisfaction following service recovery by using scenarios (Holloway et al., 2009:390; Huang, 2011:514; Karande, Magnini & Tam, 2007:187; Lin & Lin, 2011:191; Smith et al., 1999:362), this study used a quantitative research design. The study population spanned gender, population and age groups, as it comprised residents living in the Johannesburg Metropolitan area, 18 years or older, who have used a cell phone network provider for at least three years. Owing to the lack of a sampling frame, and the need to explain the scenarios used in the questionnaire (Bradley, 2007:128), non-probability convenience sampling was used to collect data by means of personal, in-home interviews conducted by 36 trained fieldworkers. Before data collection commenced, the authors obtained ethical clearance for the research project from their academic institution. The fieldworkers approached prospective respondents between 11 and 24 October 2012 at their place of residence according to a predetermined gender, population and age quota (based on the fieldworker's perception of the practicality of approaching prospective respondents for assigned quotas) to ensure a demographically diverse sample for this study. This process, however, did not result in an equal distribution of respondents according to set quotas.

4.2 Questionnaire design

The questionnaire used in the study consisted of four sections and began with a preamble explaining the respondents' rights, the purpose of the study and the screening questions. Before completing a questionnaire, respondents consented to participate voluntarily in the study without receiving any form of remuneration. The first section obtained classification and the respondents' cell phone patronage information. The second section measured respondents' relationship intentions by means of the scale proposed by Kruger and Mostert (2012:45), as it has proved to be valid and reliable for measuring relationship intention in South African service settings. The anchors of the Likert-type scale measuring relationship intention were 1 = no, definitely not, and 5 = yes, definitely.

The third section of the questionnaire presented respondents with a service failure scenario followed by a service recovery scenario. Using scenarios in service failure and recovery research is ethically and practically advantageous (Kim & Ulgado, 2012:161; Long-Tolbert & Gammoh, 2012:399; Van Vaerenbergh et al., 2014:58), as service failure and recovery do not have to be intentionally imparted to customers in order to examine their reactions, and the biases resulting from customers' recall of events are eliminated when using scenarios (Smith et al., 1999:362).

The decision was made to use a billing error as a service failure scenario, because this is widely prevalent in the cellular industry, both internationally (Chang et al., 2013:374) and nationally (ICASA, 2012:28). Respondents would regard a billing error by their cell phone network providers as realistic and conceivable. The service failure scenario read as follows:

After signing a contract with your cell phone network provider for 150 free minutes to any cell phone number during office hours, you receive your bill and see that you have in fact been charged for all the calls you made during office hours and not just for the calls exceeding the 150 minute frame.

Considerations for the service recovery scenario presented to respondents centred on the notions that combining the service recovery strategies would contribute to more effective service recovery (Tax & Brown, 1998:80-81; Wen & Chi, 2013:319) and that tangible service recovery strategies increase customer satisfaction (Bateson & Hoffman, 2011:368-369). As this study specifically considered the effects of relationship intention and perceived service recovery on satisfaction after service recovery, the service recovery scenario combined restorative and apologetic strategies, but excluded tangible service recovery strategies (in the form of compensation) so as to control for the influence of such strategies. The service recovery scenario presented asked respondents how they would feel 'if, in addition to rectifying the problem so that it would not occur in future, the cell phone network provider acknowledged the problem, apologised and explained why the problem had occurred'.

Perceived service recovery was measured by combining items adapted from Holloway et al. (2009:390), Huang (2011:514), Lin et al. (2011:522-523) and McCullough et al. (2000:127). Satisfaction after service recovery was measured by means of items adopted from Lin and Lin (2011:191). Both perceived service recovery and satisfaction after service recovery were rated on a five-point unlabelled Likert-type scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. The final section of the questionnaire captured respondents' demographic information.

Before the questionnaire was fielded, it was pretested with 27 respondents from the study population to identify and correct any potential problems respondents might have experienced when completing the questionnaire (Zikmund & Babin, 2010:61-62). No problems were identified during the pretesting and the respondents who participated in the pre-test did not take part in the main study.

4.3 Data analysis

A total of 605 usable questionnaires were obtained. Statistical processing was done with SPSS Version 21 and Mplus 7.11. Descriptive statistics, as well as the reliability and construct validity of measurement scales used in the study, were determined. A confidence level of 95 per cent was set for statistical significance throughout the data analyses. The probability of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis was thus 5 per cent (Aaker, Kumar, Leone & Day, 2013:426; Hair, Wolfinbarger Celsi, Oritinau & Bush, 2013:147; Malhotra, 2010:491).

To examine the covariance between relationship intention, perceived service recovery and satisfaction after service recovery, structural equation modelling (SEM) was used. Besides it being an appropriate statistical technique for testing theory (Babin & Svensson, 2012:320; Westland, 2010:11), the decision to use SEM was supported by similar service recovery research using the same method (Holloway et al., 2009:391; Huang, 2011:513; Robinson et al., 2011:94). The questionnaire items used for measuring the constructs of this study were used as the observed variables in the analyses. Therefore, item parcelling methods were not implemented. The 5-point Likert-type scales were used in the study for the observed variables (questionnaire items) that were considered categorical. The construct relationship intention was estimated as a second-order construct with the five underlying first-order dimensions (i.e. involvement, expectations, fear of relationship loss, feedback and forgiveness) being the first-order constructs. Relationship intention, a second-order latent variable, can therefore be presented as the captured common variance of the five underlying dimensions of relationship intention, as discussed in the literature review. The constructs of perceived service recovery and satisfaction after service recovery were proposed as first-order constructs with their observed indicators. Mplus 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2013) was chosen for the SEM analyses owing to its ability to estimate the model based on the categorical nature of the data. In Mplus, the default estimators used for model estimation that contain categorical indicators are the mean and variance-adjusted weighted least-square method (WLSMV) (Kline, 2011:181; Muthén, Du Toit & Spisic, 1997:23-25).

The fit indices considered for this study included the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Van de Schoot, Lugtig & Hox, 2012:487-488). The CFI is used for assessing the fit of the proposed model relative to the null or independence model, which assumes no relationships in the data. Values of 0.95 or greater are considered acceptable (Meyers, Gamst & Guarino, 2006:608; Van de Schoot et al., 2012:487). The TLI is an incremental fit measure for which a value of 0.90 or greater is recommended (Blunch, 2008:115; Van de Schoot et al., 2012:487). The RMSEA is an absolute fit measure (determining the degree to which the research model, measurement and structural models predict the observed covariance or correlation matrix). The RMSEA attempts to correct for the tendency of the chi-square statistic to reject any specified model with a sufficiently large sample (Blunch, 2008:116). The RMSEA is the discrepancy measured in terms of the population per degree of freedom (Hair, Anderson, Tatham & Black, 1998:654, 656). A RMSEA value ranging up to 0.08 is considered indicative of a good fit (Hair et al., 1998:654, 656; Meyers et al., 2006:608; Van de Schoot et al., 2012:488).

To investigate the potential mediating effect in the research model, bootstrapping resampling was implemented to resample 5 000 times from the data in order to generate indirect effects at the 95 per cent level of confidence (Rucker, Preacher, Tormala & Petty, 2011:362-363). Further, as the potential mediating effect is in a simple mediation model, the kappa-squared (κ2) effect size could be calculated in order to provide a descriptive label for the mediating effect (Preacher & Kelley, 2011:106). The κ2should be interpreted as for squared correlation (R2) coefficients (Preacher & Kelly, 2011:107): small effect (κ2 > 0.01); medium effect (κ2 > 0.09); and large effect (κ2 >0.25).

5 Results

5.1 Respondents' profile

Both females (53.7 per cent) and males (46.3 per cent) participated in this study. Considering respondents' population group, 33.5 per cent of the respondents were black African, 28.3 per cent were white, 21.2 per cent were Asian/Indian and 17.0 per cent were coloured. Most of the respondents used Vodacom (43 per cent) or MTN (34.4 per cent) as their cell phone network provider. Fewer respondents used Cell C (16.5 per cent), Telkom Mobile (3.3 per cent) or Virgin Mobile (2.8 per cent) as their cell phone network provider. Slightly more than half of the respondents had contracts with their cell phone network providers (52.2 per cent).

5.2 Reliability

The assessment of the reliability of a scale concerns the extent to which it would reproduce the same or similar results if the study were repeated (Hair et al., 2013:165). To determine the internal consistency reliability of relationship intention, perceived service recovery and satisfaction following service recovery scales used in this study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient and coefficient omega values were calculated. Cronbach's alpha coefficient values are calculated from the average of all the possible ways of splitting the scale items and the resultant split-half coefficients (Malhotra, 2010:319). Conversely, coefficient omega uses both the item factor loading and the uniqueness (calculated by adding the true influences, the systematic errors and the measurement errors) to estimate reliability (Padilla & Divers, 2013:78). Both alpha and omega reliabilities are generally considered acceptable at equal to or greater than 0.70 (§imsek & Tekeli, 2014:436).

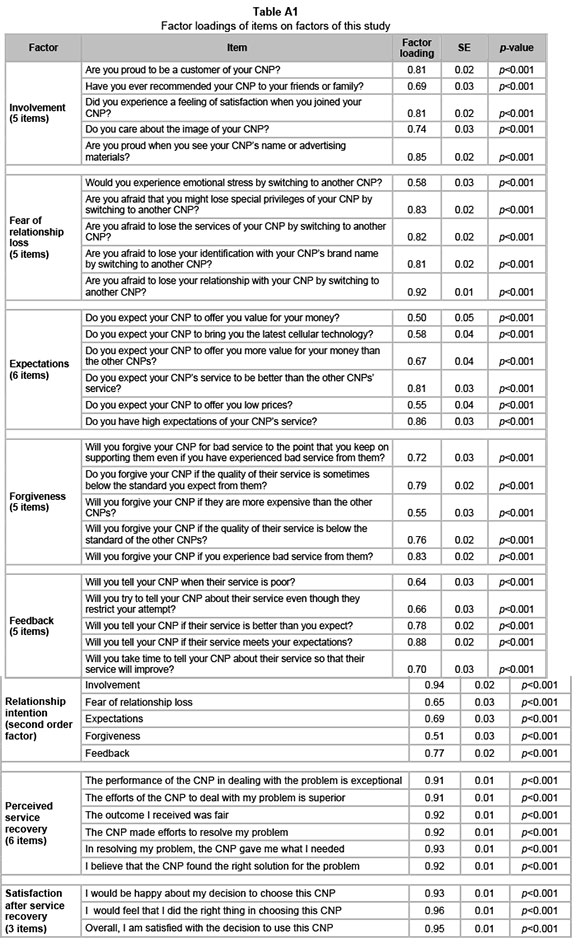

Table 1 presents the Cronbach's alpha coefficient values (or), the omega values (ω) and the mean scores for the constructs of this study.

Table 1 indicates that all the scales used in the study had Cronbach's alpha and omega coefficient values above the generally accepted guideline of 0.70. For this reason, the scales were considered reliable by the respondents who participated in this study.

The overall mean scores for respondents' relationship intentions (mean = 3.60), perceived service recovery (mean = 4.26), and satisfaction after service recovery (mean = 4.15) were all above the midpoint of the scales used. It could therefore be concluded that the majority of the respondents participating in this study tended to have higher relationship intentions towards their cell phone network providers, they perceived the service recovery positively and were satisfied with the service recovery.

5.3 Respondents' relationship intentions, perceived service recovery and satisfaction after service recovery

The relationships between respondents' relationship intentions, perceived service recovery and satisfaction following service recovery were investigated using structural equation modelling (SEM) methods. After the hypothesised model had been specified, all the indicator variables were specified as categorical data in Mplus. The variable relationship intention was considered a second-order construct in which its dimensions of involvement, expectations, fear of relationship loss, feedback and forgiveness were treated as reflective first-order constructs, while perceived service recovery and satisfaction after service recovery were proposed as first-order constructs. Service recovery is abbreviated as SR in the following tables.

5.3.1 Correlation matrix

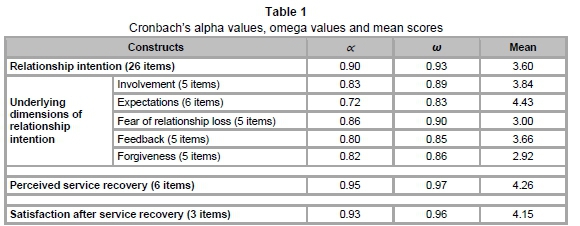

The correlation matrix of the latent variables is presented in Table 2.

In Table 2, it can be seen that all the correlations were both positive and statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level. A large positive correlation between perceived service recovery and satisfaction after service recovery (r = 0.88) was found. Some degree of multicollinearity in the structural model should be noted, which indicates that the variables were highly correlated (Malhotra, 2010:586). However, Tabachnick and Fidell (2013:90) argue that multicollinearity occurs at correlations of 0.90 and higher. Further, the variance inflation factor (VIF) value, indicating multicollinearity above 10 and considered a concern above 5 (Allen & Bennett, 2010:186), was 1.21 for perceived service recovery and that for satisfaction was 4.35.

5.3.2 Validity by considering fit indices

The measurement model was found to fit the data acceptably. The CFI (0.97) and TLI (0.97) indicated a good model fit, which was confirmed by the RMSEA (0.06). The good model fit and the positive significant loadings of all the items on the variables therefore confirm good convergent validity.

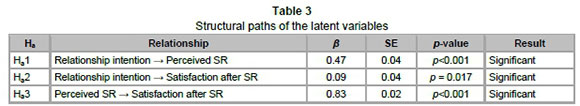

Involvement was measured by means of five items that loaded onto the intended factor at a statistically significant level (p<0.001). Factor loadings varied between 0.69 and 0.85, while standard errors (SE) varied between 0.02 and 0.03. Expectations were measured by means of six items that loaded onto the intended factor at a statistically significant level (p<0.001). The factor loadings varied between 0.50 and 0.86, and the standard errors (SE) varied between 0.03 and 0.05. Fear of relationship loss was measured by means of five items that loaded onto the intended factor at a statistically significant level (p<0.001). Factor loadings varied between 0.58 and 0.92, and standard errors (SE) varied between 0.01 and 0.03. Feedback was measured by means of five items that loaded onto the intended factor at a statistically significant level (p<0.001). Factor loadings varied between 0.64 and 0.88, and standard errors (SE) varied between 0.02 and 0.03. Forgiveness was measured by means of five items that loaded onto the intended factor at a statistically significant level (p<0.001). Factor loadings varied between 0.55 and 0.83, and standard errors (SE) varied between 0.02 and 0.03.

With regard to relationship intention as a second-order construct, the five first-order constructs (involvement, expectations, fear of relationship loss, feedback and forgiveness) all loaded onto the second-order variable at a statistically significant level (p<0.001). Factor loadings varied between 0.51 and 0.94, and standard errors (SE) varied between 0.02 and 0.03. Perceived service recovery was measured by means of six items that loaded onto the intended factor at a statistically significant level (p<0.001). Factor loadings varied between 0.91 and 0.93, and the standard errors (SE) for all items were 0.01. Satisfaction after service recovery was measured by means of three items that loaded onto the intended factor at a statistically significant level (p<0.001). The factor loadings varied between 0.93 and 0.95, and the standard errors (SE) for all items were 0.01.

The results of the confirmatory factor analysis thus indicated that all the items loaded onto each intended factor at a statistically significant level (p<0.001). The factor loadings varied between 0.50 and 0.95 and the standard errors (SE) varied between 0.01 and 0.05 for all the items. The factor loadings for all the items on the relevant factors are presented in Table A1 (see Annexure A). The structural paths were then added to the model. For the structural model, the CFI (0.95) and TLI (0.94) again indicated a good model fit, which was confirmed by the RMSEA (0.08).

5.3.3 Structural paths

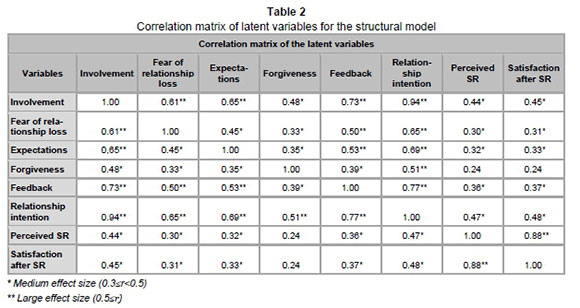

Table 3 presents the structural paths of the latent variables for the model in terms of the hypotheses (Ha), the path coefficients (β), the standard error (SE), the statistical significance at the 0.05 level (p-value), and the result.

In Table 3, it is evident that all the structural paths hypothesised in the research model were statistically significant. For this reason, Ha1, which states that there is a significantly positive relationship between cell phone users' relationship intentions and perceived service recovery, is accepted. Ha2, which states that there is a significant positive relationship between cell phone users' relationship intentions and satisfaction after the service recovery, is therefore accepted, as is Ha3, which states that there is a significant positive relationship between cell phone users' perceptions of service recovery and satisfaction after service recovery. Figure 2 presents a summary of the significant structural paths.

The results of bootstrapping resampling revealed a significant indirect effect between relationship intention and satisfaction through perceived service recovery: 0.39 (95 per cent CI [0.31, 0.47]. This result provides evidence of the mediating effect. To communicate the practical effect size of the mediating effect, the κ2value was calculated and found to be 0.47, resulting in a large effect. Moreover, as the direct path from relationship intention to satisfaction with service recovery was also significant, the mediation model could be classified as a complementary mediation model (Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, 2010:200), which is analogous to the classical claim of partial mediation (a significant indirect and direct relationship).

6 Discussion and recommendations

According to the expectancy disconfirmation theory, customers determine their satisfaction with service delivery by comparing their expectations with the disconfirmation experienced during service delivery (Churchill & Surprenant, 1982:491). When service providers fail to meet their customers' service delivery expectations, service failures (negative disconfirmation) are experienced, resulting in an unequal exchange. Service providers therefore attempt to restore customer satisfaction (Huang, 2011:513) by eliminating the perceived inequality by means of service recovery (Fang et al., 2013:344; Kau & Loh, 2006:102).

The purpose of this study was to determine customers' relationship intentions as well as their perceptions of the effect of service recovery on customer satisfaction following the recovery. The aim of this study was derived from the conviction that customers' relationship intentions would result in behaviour that would uphold their relationships when service failures occur (Kumar et al., 2003:670), and that perceived service recovery influences customer satisfaction following service recovery (Bitner, 1990:79; Huang, 2011:513; Tax & Brown, 1998:87; Wen & Chi, 2013:320).

Previous research suggests that the relationships between customers and service providers should be considered a key determinant of the service recovery required to restore post-recovery attitudes and behaviour (DeWitt & Brady, 2003:202-203; Forrester & Maute, 2001:10; Kaltcheva et al. 2013:526; Singh & Sirdeshmukh, 2000:163). The results of this study support this view, as a significant positive relationship was found between cell phone users' relationship intentions and perceived service recovery. This finding further supports Kumar et al.'s (2003:670) argument that customers with relationship intentions will exhibit behaviour that will uphold the relationship when service failures occur. In support of the suggestion by Camra-Fierro et al. (2014:16) that service providers should adapt their service recovery strategies according to the nature of the relationship with their customers, it can be recommended that cell phone network providers identify and focus their relationship marketing efforts on customers with relationship intentions based on the sub constructs of relationship intention (involvement, expectations, fear of relationship loss, feedback and forgiveness). The identified customers could hold higher (more positive) service recovery perceptions, providing the opportunity for cell phone network providers to adapt service recovery strategies according to customers' relationship intentions.

Further, the results of this study found a significant positive relationship between cell phone users' relationship intentions and satisfaction after service recovery. This finding could possibly stem from the notion that customers with relationship intentions are likely to ascribe more value to their relationships with their service providers than to unmet expectations and therefore choose to forgive their service providers (Kumar et al., 2003:670). Also, customers in a close relationship with their service providers are more likely to forgive a service failure (Karremans & Aarts, 2007:910), as forgiveness facilitates the restoration of the relationship with an offending relationship partner, rather than terminating it (Chung & Beverland, 2006:98). The fact that a positive relationship was found between customers' relationship intentions and their satisfaction after service recovery supports Ha and Jang's (2009:326) view that procedural justice, such as restorative and apologetic service recovery efforts, may be the most useful when dealing with customers with strong relationships. Cell phone network providers may therefore find that customers with relationship intentions are more satisfied following service recovery than those without relationship intentions, thereby reinforcing the recommendation to focus specifically on customers with relationship intentions.

This study determined respondents' satisfaction following service recovery by offering a service recovery scenario combining restorative and apologetic strategies, but excluding tangible service recovery strategies (in the form of compensation). From the findings it could be concluded that there is a significant positive relationship between cell phone users' perceptions of service recovery and satisfaction after service recovery. This finding supports the literature in two ways. First, there is the exclusion of any form of compensation from the service recovery scenario. This finding supports previous research in that service providers do not necessarily have to offer any form of compensation following a service failure, as customer satisfaction after service recovery can be restored by offering an apology or an explanation providing adequate and truthful information about the service failure (Blodgett et al., 1997:202; Smith et al., 1999:369; Wang & Mattila, 2011:434). Secondly, the positive relationship between cell phone users' perceptions of service recovery and their satisfaction after service recovery support the literature suggesting that positively perceived service recovery is essential to restoring customer satisfaction (Bitner, 1990:79; Huang, 2011:513; Tax & Brown, 1998:87; Wen & Chi, 2013:320). It can therefore be recommended that, as advocated by Camra-Fierro et al. (2014:16), cell phone network providers should always invest resources in service recovery strategies. In particular, it can be recommended that, instead of offering some form of compensation as a service recovery strategy, cell phone network providers apologise for the service failure, explain why it occurred, and rectify the problem so that it will not occur again in future.

Finally, this study found that perceived service recovery plays a mediating role in the relationship between relationship intention and satisfaction following service recovery. Thus, although there is a direct relationship between relationship intention and satisfaction following service recovery, perceived service recovery plays an additional indirect complementary role in this relationship. Previous studies suggest that the influence of the relationship between customers and their service providers (Holloway et al., 2009:386; Long-Tolbert & Gammoh, 2012:398; Mattila, 2004:144;), as well as positively perceived service recovery (Bitner, 1990:79; Huang, 2011:513; Tax & Brown, 1998:87; Wen & Chi, 2013:320) are essential to restoring customer satisfaction following service recovery. Despite these findings, previous studies did not consider the influence of both customer relationships (i.e. relationship intention) and perceived service recovery on satisfaction following service recovery. The findings from this study therefore offer a unique contribution insofar as it has been established that, over and above the other relationships that were uncovered, perceived service recovery acts as the mediator between customers' relationships (in the form of relationship intentions) and satisfaction with service recovery. It can therefore be recommended that cell phone network providers, as well as other service providers with similar customers, understand the importance of offering effective service recovery to customers who display relationship intentions. Despite Kumar et al.'s (2003:670) suggestion that customers with relationship intentions will forgive service providers for the occasional service failure, findings from this study show that service providers should err on the side of caution by offering positively perceived service recovery to customers with relationship intentions. Doing so would lead to greater satisfaction following service recovery.

7 Limitations and future research

A number of limitations to the study should be noted. Owing to the use of non-probability convenience sampling, the findings of the study cannot be generalised beyond the study population and the geographical area where it was conducted. Also, although they are commonly used in service failure research (Kim & Ulgado, 2012:161; Long-Tolbert & Gammoh, 2012:399; Van Vaerenbergh et al., 2014:58), service failure and service recovery scenarios prevent generalisation of the findings, as other scenarios (or actual real-life service failure and recovery recollections) could have returned different findings.

Future research could consider the influence of customers' relationship intentions on different service failure and service recovery scenarios. Specifically, future research could consider the influence of relationship intention on core service as well as peripheral service failures by including a study of different degrees of seriousness of each type of failure. The influence of relationship intention on procedural justice, interactional justice and distributive justice could also be investigated. Further, research should cover brand equity, which enhances satisfaction following service recovery (Huang, 2011:514), expectations of service recovery (Bhandari, Tsarenko & Polonsky, 2007:181) and the type of service failure (Smith et al., 1999:369) which may influence satisfaction after service recovery. Finally, future research could expand the model proposed in this study by including other relationship-related outcomes, such as customer loyalty and retention.

References

AAKER, D.A., KUMAR, V., LEONE, R.P. & DAY, G.S. 2013. Marketing research (11th ed.) Danvers, M.A.: Wiley. [ Links ]

ALLEN, P. & BENNETT, K. 2010. PASW statistics by SPSS: A practical guide, version 18.0. Australia: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

ANDERSON, E.W., FORNELL, C. & LEHMANN, D.R. 1994. Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: findings from Sweden. Journal of Marketing, 58:53-66, July. [ Links ]

ANDREASSEN, T.W. 2000. Antecedents to satisfaction with service recovery. European Journal of Marketing, 34(1/2):156-175. [ Links ]

BABIN, B.J. & SVENSSON, G. 2012. Structural equation modelling in social science research: Issues of validity and reliability in the research process. European Business Review, 24(4):320-330. [ Links ]

BATESON, J.E.G. & HOFFMAN, K.D. 2011. Services marketing (4th int. ed.) Canada: South-Western Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

BEETLES, A.C. & HARRIS, L.C. 2010. The role of intimacy in service relationships: An exploration. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(5):347-358. [ Links ]

BERRY, L.L. & PARASURAMAN, A. 1997. Listening to the customer - the concept of a service-quality information system. Sloan Management Review, 38(3):65-76, Spring. [ Links ]

BHANDARI, M.S., TSARENKO, Y. & POLONSKY, M.J. 2007. A proposed multi-dimensional approach to evaluating service recovery. Journal of Services Marketing, 21(3):174-185. [ Links ]

BITNER, M.J. 1990. Evaluating service encounters: The effects of physical surroundings on employee responses. Journal of Marketing, 54:69-82, April. [ Links ]

BLODGETT, J.G., HILL, D.J. & TAX, S.S. 1997. The effects of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice on postcomplaint behavior. Journal of Retailing, 73(2):185-210. [ Links ]

BLOEMER, J. & DE RUYTER, K. 1999. Customer loyalty in high and low involvement service settings: The moderating impact of positive emotions. Journal of Marketing Management, 15:315-330. [ Links ]

BLUNCH, N.J. 2008. Introduction to structural equation modelling using SPSS and AMOS. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

BOLTON, R.N. & CHRISTOPHER, R.M. 2014. Building long-term relationships between service organizations and customers. Published in Rust, R.T. & Huang M. (eds.) Handbook of Service Marketing Research. Cheltenham, UK: Elgar:11-36. [ Links ]

BRADLEY, N. 2007. Marketing research: Tools and techniques. New York, N.J.: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

CAEMMERER, B. & WILSON, A. 2010. Customer feedback mechanisms and organisational learning in service operations. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 30(3):288-311. [ Links ]

CANT, M.C. & ERDIS, C. 2012. Incorporating customer service expectations in the restaurant industry: The guide to survival. The Journal of Applied Business Research, 28(5):931-942, Sept./Oct. [ Links ]

CAMRA-FIERRO, J., MELERO-POLO, I. & SESE, J. 2014. Does the nature of the relationship matter? An analysis of the roles of loyalty and involvement in service recovery processes. Service Business: 1-24, Jan. [ Links ]

CHAN, H. & WAN, L.C. 2008. Consumer responses to service failures: A resource preference model of cultural influences. Journal of International Marketing, 16(1):72-97. [ Links ]

CHANG, H.C., TSAI, Y.C. & HSU, S.Y. 2013. The effects of relationship-destroying factors on customer relationships: Relationship recovery as the moderator. Contemporary Management Research, 9(4):369-388. [ Links ]

CHUNG, E. & BEVERLAND, M. 2006. An exploration of consumer forgiveness following marketer transgressions. Advances in Consumer Research, 33:98-99. [ Links ]

CHURCHILL, G.A., & SURPRENANT, C. 1982. An investigation into the determinants of customer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(4):491-504, Special issue on causal modeling, Nov. [ Links ]

DAGGER, T.S. & DAVID, M.E. 2012. Uncovering the real effect of switching costs on the satisfaction-loyalty association: The critical role of involvement and relationship benefits. European Journal of Marketing, 46(3/4):447-468. [ Links ]

DEWITT, T. & BRADY, M.K. 2003. Rethinking service recovery strategies: The effect of rapport on consumer responses to service failures. Journal of Service Research, 6(2):193-207. [ Links ]

DEWITT, T., NGUYEN, D.T. & MARSHALL, R. 2008. Exploring customer loyalty following service recovery: The mediating effects of trust and emotions. Journal of Service Research, 10(3):269-281. [ Links ]

DORAI, S. & VARSHNEY, S. 2012. A multistage behavioural and temporal analysis of CPV in RM. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 27(5):403-411. [ Links ]

DU, J., FAN, X. & FENG, T. 2010. An experimental investigation of the role of face in service failure and recovery encounters. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 27(7):584-593. [ Links ]

EGAN. J. 2011. Relationship marketing: Exploring relational strategies in marketing (4th ed.) Harlow: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

FANG, Z., LUO, X. & JIANG, M. 2013. Quantifying the dynamic effects of service recovery on customer satisfaction: Evidence from Chinese mobile phone markets. Journal of Service Research, 16(3):341-355. [ Links ]

FORRESTER, W.R. & MAUTE, M.F. 2001. The impact of relationship satisfaction on attributions, emotions, and behaviour following service failure. The Journal of Applied Business Research, 17(1):1-14. [ Links ]

FOURNIER, S. & MICK, D.G. 1999. Rediscovering satisfaction. Journal of Marketing, 63(4):5-23. [ Links ]

GWINNER, K.P., GREMLER, D.D. & BITNER, M.J. 1998. Relational benefits in services industries: The customer's perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26(2):101-114. [ Links ]

HA, J. & JANG, S.S. 2009. Perceived justice in service recovery and behavioral intentions: The role of relationship quality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28:319-327. [ Links ]

HAENLEIN, M. & KAPLAN, A.M. 2012. The impact of unprofitable customer abandonment on current customers' exit, voice, and loyalty intentions: An empirical analysis. Journal of Services Marketing, 26(6):458-470. [ Links ]

HAIR, J.F., ANDERSON, R.E., TATHAM, R.L. & BLACK, W.C. 1998. Multivariate data analysis (5th int. ed.) Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

HAIR, J.F., WOLFINBARGER CELSI, M., ORITINAU, D.J. & BUSH, R.P. 2013. Essentials of marketing research (3rd int. ed.) New York, N.Y.: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

HARRISON-WALKER, L.J. 2012. The role of cause and effect in service failure. Journal of Services Marketing, 26(2):115-123. [ Links ]

HEDRICK, N., BEVERLAND, M. & MINAHAN, S. 2007. An exploration of relational customers' response to service failure. Journal of Services Marketing, 21(1):64-72. [ Links ]

HENNIG-THURAU, T., GWINNER, K.P. & GREMLER, D.D. 2002. Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. Journal of Service Research, 4(3):230-247. [ Links ]

HESS, R.L., GANESAN, G. & KLEIN, N.M. 2003. Service failure and recovery: The impact of relationship factors on customer satisfaction. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(2):127-145. [ Links ]

HESS,J., STORY, J. & DANES, J. 2011. A three-stage model of consumer relationship investment. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 20(1):14-26. [ Links ]

HOLLOWAY, B.B., WANG, S. & BEATTY, S.E. 2009. Betrayal? Relationship quality implications in service recovery. Journal of Services Marketing, 23(6):385-396. [ Links ]

HOMBURG, C. & GIERING, A. 2001. Personal characteristics as moderators of the relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty - an empirical analysis. Psychology & Marketing, 18(1):43-66. [ Links ]

HOMBURG, C., GIERING, A. & MENON, A. 2003. Relationship characteristics as moderators of the satisfaction-loyalty link: Finding in a business-to-business context. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 10(3):35-62. [ Links ]

HUANG, M.H. 2011. Re-examining the effect of service recovery: The moderating role of brand equity. Journal of Services Marketing, 25(7):509-516. [ Links ]

INDEPENDENT COMMUNICATIONS AUTHORITY OF SOUTH AFRICA (ICASA). 2012. Strategic plan for the fiscal years 2013-2017. Available at: http://www.icasa.org.za/Portals/0/Regulations/AnnualReports/StrategicPlan13-17/SPlan1317.pdf [accessed 2013-03-18]. [ Links ]

KALTCHEVA, V.D., WINSOR, R.D. & PARASURAMAN, A. 2013. Do customer relationships mitigate or amplify failure responses? Journal of Business Research, 66:525-532. [ Links ]

KARANDE, K., MAGNINI, V.P. & TAM, L. 2007. Recovery voice and satisfaction after service failure: An experimental investigation of mediating and moderating factors, Journal of Service Research, 10(2):197-2013. [ Links ]

KARREMANS, J.C. & AARTS, H. 2007. The role of automaticity in determining the inclination to forgive close others. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43:902-917. [ Links ]

KAU, A.K. & LOH, E.W.Y. 2006. The effects of service recovery on consumer satisfaction: A comparison between complainants and non-complainants. Journal of Services Marketing, 20(2):101-111. [ Links ]

KIM, W., OK, C. & CANTER, D.D. 2012. Moderating role of a priori customer-firm relationship in service recovery situations. The Service Industries Journal, 32(1):59-82, Jan. [ Links ]

KIM, N. & ULGADO, F.M. 2012. The effect of on-the-spot versus delayed compensation: The moderating role of failure severity. Journal of Services Marketing, 26(3):158-167. [ Links ]

KINARD, B.R. & CAPELLA, M.L. 2006. Relationship marketing: The influence of consumer involvement on perceived service benefits. Journal of Services Marketing, 20(6):359-368. [ Links ]

KLINE, R.B. 2011. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.) New York, N.Y.: Guilford. [ Links ]

KOMUNDA, M. & OSARENKHOE, A. 2012. Remedy or cure for service failure? Effects of service recovery on customer satisfaction and loyalty. Business Process Management Journal, 18(1):82-103. [ Links ]

KRUGER, L. & MOSTERT, P.G. 2012. Young adults' relationship intentions towards their cell phone network operators. South African Journal of Business Management, 43(2):15-23. [ Links ]

KUMAR, V., BOHLING, T.R. & LADDA, R.N. 2003. Antecedents and consequences of relationship intention: Implications for transaction and relationship marketing. Industrial Marketing Management, 32(8):667-676. [ Links ]

LIANG, C.J. & WANG, W.H. 2006. The behavioural sequence of the financial services industry in Taiwan: Service quality, relationship quality and behavioural loyalty. Service Industries Journal, 26(2):119-145. [ Links ]

LIN, J.S.C. & LIN, C.Y. 2011. What makes service employees and customers smile? Antecedents and consequences of the employees' affective delivery in the service encounter. Journal of Service Management, 22(2):183-201. [ Links ]

LIN, H.H., WANG, Y.S. & CHANG, L.K. 2011. Consumer responses to online retailers' service recovery after a service failure. Managing Service Quality, 21(5):511-534. [ Links ]

LONG-TOLBERT, S.J. & GAMMOH, B.S. 2012. In good and bad times: The interpersonal nature of brand love in service relationships. Journal of Service Marketing, 26(6):391-402. [ Links ]

MALHOTRA, N.K. 2010. Marketing research: An applied orientation (6th global ed.) Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson. [ Links ]

MALHOTRA, A. & MALHOTRA, C.K. 2013. Exploring switching behavior of US mobile service customers. Journal of Services Marketing, 27(1):13-24. [ Links ]

MATTILA, A.S. 2001. The effectiveness of service recovery. Journal of Services Marketing, 15(7):583-596. [ Links ]

MATTILA, A.S. 2004. The impact of service failures on customer loyalty: The moderating role of affective commitment. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 15(2):134-149. [ Links ]

MBENDI. 2011. Communications and infrastructure. Available at: http://www.mbendi.com/land/af/sa/p0005.htm - 30 [accessed 2012-03-08]. [ Links ]

MCCULLOUGH, M.A., BERRY, L.L. & YADAV, M.S. 2000. An empirical investigation of customer satisfaction after service failure and recovery. Journal of Service Research, 3(2):121-137. [ Links ]

MCCULLOUGH, M.E., FINCHAM, F.D. & TSANG, J.A. 2003. Forgiveness, forbearance and time: The temporal unfolding of transgression-related interpersonal motivations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3):540-557. [ Links ]

MEYERS, L.S., GAMST, G. & GUARINO, A.J. 2006. Applied multivariate research: Design and interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

MUTHÉN, B.O., DU TOIT, S.H.C. & SPISIC, D. 1997. Robust inference using weighted least squares and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes. Available at: http://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/muthn/articles/Article_075.pdf [accessed 2013-07-04]. [ Links ]

MUTHÉN, L.K. & MUTHÉN, B.O. 1998-2013. Mplus for Windows 7.11, Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA. Available at: http://www.statmodel.com. [ Links ]

NIKBIN, D., ISMAIL, I., MARIMUTHU, M. & ABU-JARAD, I.Y. 2011. The impact of firm reputation on customers' responses to service failure: The role of failure attributions. Business Strategy Series, 12(1):19-29. [ Links ]

OLIVER, R.L. 1980. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4):460-469. [ Links ]

PADILLA, M.A. & DIVERS, J. 2013. Bootstrap interval estimation of reliability via Cronbach Omega. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, 12(1):78-89. [ Links ]

PETRUZZELLIS, L. 2010. Mobile phone choice: Technology versus marketing. The brand effect in the Italian market. European Journal of Marketing, 44(5):610-634. [ Links ]

PREACHER, K. J. & KELLEY, K. 2011. Effect sizes measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods, 16(2):93-115. [ Links ]

RAINBOW NATION. 2011. Relocating to South Africa - Communication companies. Available at: http://www.rainbownation.com/services/southafrica/communications.asp [accessed 2011-01-07]. [ Links ]

ROBINSON, L., NEELEY, S.E. & WILLIAMSON, K. 2011. Implementing service recovery through customer relationship management: Identifying the antecedents. Journal of Service Marketing, 25(2):90-100. [ Links ]

RUCKER, D. D., PREACHER, K. J., TORMALA, Z. L. & PETTY, R. E. 2011. Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5/6:359-371. [ Links ]

SEAWRIGHT, K.K., DETIENNE, K.B., BERNHISEL, M.P. & LARSON, C.L.H. 2008. An empirical examination of service recovery design. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 26(3):253-274. [ Links ]

SEO, D., RANGANATHAN, C. & BABAD, Y. 2008. Two-level model of customer retention in the US mobile telecommunications service market. Telecommunications Policy, 32:182-196. [ Links ]

SIMSEK, G.G. & TEKELI, F.N. 2014. Understanding the antecedents of customer loyalty by applying structural equation modeling. Published in Akkucuk, U. (ed.) Handbook of research on developing sustainable value in economics, finance, and marketing. Hershey, PA: IGI Global:420-445. [ Links ]

SINGH, J. & SIRDESHMUKH, D. 2000. Agency and trust mechanisms in consumer satisfaction and loyalty judgments. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1):150-167. [ Links ]

SMITH, A.K. & BOLTON, R.N. 2002. The effect of consumers' emotional responses to service failures on their recovery effort evaluations and satisfaction judgments, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(1):5-23. [ Links ]

SMITH, A.K., BOLTON, R.N. & WAGNER, J. 1999. A model of consumer satisfaction with service encounters involving failure and recovery. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(3):356-372, Aug. [ Links ]

SOLOMON, M.R. 2005. Transfer of power: The hunter gets captured by the game. Marketing Research, 17(1):26-31. [ Links ]

SPAKE, D.F. & MEGEHEE, C.M. 2010. Consumer sociability and service provider expertise influence on service relationship success. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(4):314-324. [ Links ]

SPSS Inc. 2013. SPSS® 21.0 for Windows, release 21.0.0, Copyright© by SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois. Available at: http://www.spss.com. [ Links ]

STRELAN, P. & COVIC, T. 2006. A review of forgiveness process models and a coping framework to guide future research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(10):1059-1085. [ Links ]

STONE, M. 2002. Forgiveness in the workplace. Industrial and Commercial Training, 34(7):278-286. [ Links ]

TABACHNICK, B.G. & FIDELL, L.S. 2013 Using multivariate statistics (6th int. ed.) Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson. [ Links ]

TAX, S.S. & BROWN, S.W. 1998. Recovering and learning from service failure. Sloan Management Review, 49(1):75-88. [ Links ]

TAX, S.S., BROWN, S.W. & CHANDRASHEKARAN, M. 1998. Customer evaluations of service complaint experiences: Implications for relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 62:60-76. [ Links ]

TSAI, C., YANG, Y. & CHENG, Y. 2014. Does relationship matter? - Customers' response to service failure. Managing Service Quality, 24(2):139-159. [ Links ]

TSARENKO, Y. & TOJIB, D.R. 2011. A transactional model of forgiveness in the service failure context: A customer-driven approach. Journal of Services Marketing, 25(5):381-392. [ Links ]

VAN DE SCHOOT, R., LUGTIG, P. & HOX, J. 2012. A checklist for testing measurement invariance. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(4):486-492. [ Links ]

VAN NIEKERK, L. 2012. South Africa yearbook 2011/12 - Communications. Available at: http://www.gcis.gov.za/sites/www.gcis.gov.za/files/docs/resourcecentre/yearbook2011/10_Communications.pdf [accessed 2013-03-18]. [ Links ]

VAN VAERENBERGH, Y., DE KEYSER, A. & LARIVIÈRE, B. 2014. Customer intentions to invoke service guarantees: Do excellence in service recovery, type of guarantee and cultural orientation matter? Managing Service Quality, 24(1):45-62. [ Links ]

VARKI, S. & WONG, S. 2003. Consumer involvement in relationship marketing of services. Journal of Service Research, 6(1):83-91. [ Links ]

WANG, C. & MATTILA, A.S. 2011. A cross-cultural comparison of perceived informational fairness with service failure explanations. Journal of Services Marketing, 75(6):429-439. [ Links ]

WEN, B. & CHI, C.G. 2013. Examine the cognitive and affective antecedents to service recovery satisfaction: A field study of delayed airline passengers. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(3):306-327. [ Links ]

WESTLAND, J.C. 2010. Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 9(6):476-487. [ Links ]

WIRTZ, J. & MATTILA, A.S. 2004. Consumer responses to compensation, speed of recovery and apology after a service failure. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 15(2):150-166. [ Links ]

WIRTZ, J., TAMBYAH, S.K. & MATTILA, A.S. 2010. Organizational learning from customer feedback received by service employees: A social capital perspective. Journal of Service Management, 21(3):363-387. [ Links ]

YI, Y. & LEE, J. 2005. An empirical study on the customer responses to service recovery in the context of service failure. Seoul Journal of Business, 11(1):1-17. [ Links ]

YU, Y.T. & DEAN, A. 2001. The contribution of emotional satisfaction to consumer loyalty. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 12(3):234-250. [ Links ]

ZAICHOWSKY, J.L. 1985. Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(December). [ Links ]

ZAYER, L.T. & NEIER, S. 2011. An exploration of men's brand relationships. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 14(1):83-104. [ Links ]

ZHAO, X., LYNCH, J. G., & CHEN, Q. 2010. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2):197-206. [ Links ]

ZIKMUND, W.G. & BABIN, B.J. 2010. Exploring marketing research (10th ed.) Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western. [ Links ]

ZEITHAML, V.A., BERRY, L.L. & PARASURAMAN, A. 1993. The nature and determinants of customer expectations of service. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 21(1):1-12. [ Links ]

Accepted: September 2015

Annexure A: Factor loadings of items on factors of this study

Factor loadings of all items on the relevant factor are presented in Table A1. Table A1 presents the factors, the items used for measuring the factors, the factor loading, the standard error (SE) and the significance level (p-value). Cell phone network provider is abbreviated as CNP in Table A1.