Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

On-line version ISSN 2222-3436

Print version ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.18 n.4 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2222-3436/2015/V18N4A9

ARTICLES

Justice perceptions of performance management practices in a company in the chemical industry

Thanasagree GovenderI; Anton GroblerI; Yvonne T JoubertII

IGraduate School for Business Leadership, University of South Africa

IIDepartment of Human Resource Management, University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

The sustainability of corporations globally is becoming increasingly problematic. Combined with the unique challenges of an operating entity, this could potentially expose the profitability of sustainable businesses on a daily basis. The purpose of this study is to evaluate employees' justice perceptions of performance management practices in a company in the chemical industry. The population includes all the employees in the chemical industry that was used in this study. A total of 140 questionnaires were issued to all the employees in an organisation which had undergone a performance appraisal and 102 respondents completed the surveys, giving a response rate of 72 per cent. A cross-sectional survey design was used in this study. The justice perceptions were measured according to an existing framework developed by Thurston and McNall (2010). The framework is founded on a hypothesised four-factor model constructed according to theories on organisational justice. The employees of the organisation in the chemical sector were involved in this study. Descriptive statistical analyses were used to measure perceptions of justice based on theories on organisational justice. The measuring instrument used was based on recognised models and theories. The study supports the construct validity of the measuring instrument and the reliability of the scales used. The justice constructs were used to identify specific items in the performance management practice that required improvement. The implications of the results are that continual interventions are required if employee commitment and productivity levels are to improve, resulting in a positive impact on business performance. Significant differences in perceptions by demographic groups were reported and discussed. This study explored the importance of understanding justice perceptions of performance management practices as an enabler for sustained business performance. Further, the study confirmed that justice perceptions have a direct impact on both the organisational climate and employee morale.

Key words: performance management, performance management practices, performance appraisal

1 Introduction

The survival of businesses in the 21st century depends largely on organisational climate. The organisational competencies and capabilities that steered companies to success in the past will almost certainly not guarantee any success going forward. Managers are charged with delivering higher economic returns, improving productivity and reducing cost. However, performance management could help steer an organisation towards an environment that has a competitive advantage. The introduction of formal performance systems, mainly in the form of performance appraisals, has become a key aspect of organisational strategy and with performance appraisal now finding its place in organisational objectives, employee perceptions of justice have grown in importance (Rowland & Hall, 2012).

Organisational justice is central to understanding employee perceptions and reactions to the performance management process (Palaiologos, Papazekos & Panayotopoulou, 2011). There is substantial research that examines the impact of organisational justice perceptions on employee attitudes and the role and effectiveness of managers (Geeta, Pooja & Renu, 2011; Colquitt & Rodell, 2011; Wang, Liao, Xia & Chang, 2010). With performance management being viewed as one of the most important human resources systems (Blume, Baldin & Rubin, 2009; Ikramullah, Shah, Hassan, Zaman & Khan, 2011; Tuytens & Devos, 2012), any negative attitude towards the system arising from employee perceptions is seen as causing conflict and unhappiness (Thurston & McNall, 2010). This results in lower employee productivity and may ultimately determine the success or failure of the organisation (Ikramullah, et al., 2011).

Research on performance appraisals has traditionally focused on a measurement-centred approach (job performance measurement, appraisal formatting and rater bias) whereas currently the focus is on a more context-centred approach (motivational, communication, social process with interaction between the employees and supervisors and employees and organisations) (Zheng, Zhang & Li, 2012). It has been argued that for an appraisal process to be considered fair, there should be employee involvement in the development and participation of the appraisal system, as this results in trust and conveys a sense of ownership in the process (Tuytens & Devos, 2012), especially as procedures continue to develop over time (Payne, Horner, Boswell, Schroeder & Stine-Cheyne, 2009). According to Tuytens and Devos (2012), employees' behaviour is influenced by perceptions of justice that may explain reactions to the appraisal procedures and processes.

Justice trajectories will be used to evaluate past performance experiences contributing to justice theories and the validity in explaining employee behaviours and attitudes. The purpose of this study is to evaluate employees' justice perceptions of performance management practices of a company in the chemical sector.

2 Theoretical models of justice

Ethical models indicate that Aristotle believed that justice involved people receiving that which they deserved with outcomes of utilitarianism/fairness towards happiness. Stakeholder theory or the concept of the "sustaining corporation" also makes a positive contribution to human well-being. Deontological models regard rightness to be crucial and justice to be a reward in itself. Utilitarianism models quote the significance of environmental organisational culture on fair treatment and recognition (Rowland & Hall, 2012).

The "fairness heuristic theory" uses time to explain how just judgments develop. According to this theory, individuals use ongoing exchanges with supervisors, procedures and outcomes to create just judgments in order to decide whether organisations are fair (Hausknecht, Sturman & Roberson, 2011). Fairness heuristics are created during a "judgmental phase" based on accessible information which individuals then use as a guide for their subsequent behaviours (Hausknecht, Sturman & Roberson, 2011; Colquitt & Rodell, 2011). Perceptions are re-evaluated according to new information received or changes in the work environment. Research has supported this trend, as justice perceptions change across time, and the extent and direction of change varies, not only within a person but between individuals. as well, highlighting the dynamic perceptions of justice (Hausknecht et al., 2011). Employees' perceptions of performance management practices are thus of fundamental importance (Farndale, Hope-Hailey & Kelliher, 2011; Tuytens & Devos, 2012) and can be explained with the help of organisational justice theories.

3 Organisational justice theories

Organisational justice is concerned with the fair allocation of the organisation's resources, the fairness of the systems and processes according to which decisions are made, and the fairness of interpersonal treatment (Rowland & Hall, 2012). It is a useful concept whereby the outcomes and processes can be examined and it explains why employees retaliate against inequitable outcomes or inappropriate processes and interactions (Al-Zu'bi, 2010). Moreover, it forms a central part of the psychological contract and the employee's effort (Rowland & Hall, 2012; Thurston & McNall, 2010).

According to Thurston and McNall (2010), the literature on organisational justice provides a strong structure for understanding an employee's perception of performance appraisals. Organisational justice is grounded in social exchange theory, which makes two basic assumptions about human behaviour: (1) social relationships, which are the exchange processes whereby people make contributions, in return for which they expect certain outcomes, and (2) individuals evaluate the fairness of these exchanges using information gained through social interactions (Thurston & McNall, 2010). The theory further states that, besides the economic exchange relationship that results, a social exchange relationship with the company is formed (Wang et al., 2010). Earlier research by Rowland and Hall (2012) also proposes that organisational justice is established to determine the values of justice in social interaction, not necessarily just in organisations. Earlier research using meta-analysis supports four distinct justice constructs of procedural, distributive, interpersonal and informational justice (Thurston & McNall, 2010).

Three types of justice emerge from the literature relating to employees' perceptions, namely: distributive and procedural justice being the traditional two types, with the recently-introduced interactional justice as the third (Tuytens & Devos, 2012; Wang & Nayir, 2010; Wang, et al., 2010). Distributive justice refers to the justice of the outcomes of a decision process, while procedural justice relates to the justice of the process itself. Interactional justice encompasses the quality of interpersonal treatment an employee receives from the supervisor of a procedure during performance appraisal (Tuytens & Devos, 2012; Al-Zu'bi, 2010). There is some discussion as to whether or not interactional justice should be seen as an element of procedural justice (Tuytens & Devos, 2012). However, Rowland and Hall (2012) report that recently there has been a theoretical separation within procedural justice leading to a third category of justice, that of interactional justice. Interactional justice has, at times, been divided into interpersonal justice, which refers to the way people are treated, and informational justice, which informs people about distribution outcomes and procedures that have been followed (Rowland & Hall, 2012; Day, 2011; Al-Zu'bi, 2010; Colquitt & Rodell, 2011).

Distributive justice refers to the perceived fairness of the outcomes of a decision involving two or more parties (Aggarwal-Gupta & Kumar, 2010). A fair exchange in which each employee receives an outcome proportionate to his/her contribution to the exchange is defined by the equity principle (Aggarwal-Gupta & Kumar, 2010). An employee can condition the quality and quantity of work by using the equity theory if he/she perceives the outcome/input ratio to be unjust (Wang, et al., 2010). Empirical studies have found that underpaid employees reduce their contribution to decrease their performance and likewise increase their performance to increase their contribution when they are overpaid (Wang et al., 2010). Employees compare their own input contribution versus outcome ratios with those of others (Rowland & Hall, 2012). When distributive justice is perceived to be favourable, it results in employees using a more cooperative conflict management style when interacting with their managers (Geeta et al., 2011). The equity theory provides a theoretical explanation for the effect of distributive justice on performance (Wang, et al. 2010:662).

The second theoretical base for distributive justice is the relative deprivation theory, in which the fairness of the distribution is viewed through comparisons with others and perceived injustice if they have received less. This theory is based on the upward comparison made by people lower in the organisation (Aggarwal-Gupta & Kumar, 2010). Procedural justice results from the perceived fairness of policies, procedures, process and decision control, and the application of rules, demonstrating that the organisation values its employees' and managements' trustworthiness (Day, 2011; Aggarwal-Gupta & Kumar, 2010). Procedural justice is achieved when procedures are unbiased, applied consistently, are based on accurate information applicable with righteous standards and there is a process to review poor decisions (Day, 2011; Aggarwal-Gupta & Kumar, 2010). If the process is considered fair, then the decisions that are made will be more acceptable (Wang & Nayir, 2010). Most of the work carried out on procedural justice has focused on employees' perceptions of how they were treated by the supervisors and companies, with limited research on the influence of the managers' role in procedural justice (Wang & Nayir, 2010). Procedural justice was found to be a key factor for effective organisational change efforts, while the employee perception of procedural justice leads to a stronger level of organisational commitment and job satisfaction (Geeta et al., 2011). According to Al-Zu'bi (2010), the emphasis has slowly shifted to procedural justice, as procedures are used to determine outcomes and are more influential than the outcome itself.

Thurston and McNall (2010) point out that interactional justice consisted of interpersonal justice (the quality of the treatment received by the ratee) and information justice (procedural explanations of why something has happened). These dimensions had unique effects on interpersonal and informational justice. Regarding interactional justice and agent-system theory, Day (2011) points out that little research has been carried out on how interpersonal and informational justice relate to important outcomes. The agent-system model proposes that interpersonal and informational justice are associated with "agent-referenced outcomes" where outcomes are found in an "agent", usually the supervisor. The supervisor thus has control over the outcome decision, such as in determining performance ratings, job satisfaction and organisational citizenship behaviours (Day, 2011; Al-Zu'bi, 2010).

In this study, organisational justice, which is based on Thurston and McNall's (2010) hypothesised four-dimensional justice models of procedural justice, distributive justice, interpersonal justice and informational justice, will be used. This model was the most comprehensive of all the models found in the literature. As performance management practices are an interactive process involving the employees and the managers, where the outcome is influenced mainly by the manager, understanding the dynamics at play and the employees' perceptions of the interaction will provide insight into the employee's reaction.

4 Performance management practices and organisational justice

According to Kondrasuk (2011), performance appraisal has more influence on individual careers and work lives than any other management process. Performance appraisal is also recognised as one of the most important human resource practices (Tuytens & Devos, 2012). Performance appraisal is a complex process requiring the supervisor to make subjective judgments on an employee's performance. This is in comparison with an objective assessment based on the quantifiable aspects of job performance (Brown, Hyatt & Benson, 2010). According to Jawahar (2007), the effectiveness and viability of the appraisal systems are determined by reactions to the appraisal, as well as the appraisal process, with unfavourable reactions impairing the most carefully built appraisal system. Because objective measures are available for only a limited number of jobs, dependence on evaluative judgments continues (Murphy, 2008). There has been limited progress in improving the assessment of performance from the performance appraisals (Murphy, 2008) to numerous rating scale formats, identifying specific types of rating errors, rater training to systems developed to provide feedback from employees, peers, other managers and maybe customers as well to provide a wider perspective on performance (Murphy, 2008; Rowland & Hall, 2012). There has also been a shift away from subjective assessments towards a collaborative approach, involving setting of objectives and analysing developmental needs (Rowland & Hall, 2012).

Research has shown that justice perceptions affect employees' behaviour (thinking, feeling and behaving) (Farndale et al., 2011). This perception is important for the perceived effectiveness and usefulness for users and it may predict reactions to performance management practices, in particular the performance appraisal system within the organisation (Tuytens & Devos, 2012). Thus, alignment of the performance appraisal system with employees' perceptions of fair appraisal is likely to increase appraisal acceptance and success (Chen & Eldridge, 2010).

According to Simmons (2008), organisations are reliant on employee contribution and commitment for the effective operation of their organisation and they can also negate performance enhancement initiatives. An effective performance system requires managers who are aware of the systems and who can implement it (Baird, Schoch & Chen, 2012). Therefore, managers play a key role in ensuring that the process and the outcome from the performance management process are seen as fair. Fairness perceptions of performance management practices have implications both for the employees and for the organisation (Ikramullah et al., 2011). Engaging in effective performance management practices can lead to improved organisational performance, and can contribute to important outcomes such as improved employee involvement, commitment and motivation (Ikramullah et al., 2011; Baird et al., 2012). Variables pertaining to fairness include having a supervisor who is familiar with the process, processes that allow employees the opportunity to seek clarification on feedback, change ratings that are perceived to be unfair and satisfaction with performance objectives and feedback (Farndale et al., 2011; Ikramullah, et al., 2011).

Jawahar (2007) analysed the influence of fairness perceptions on satisfaction with the components of the appraisal process by looking at selected appraisal reactions as well as the type of justice perceptions that reflected the appraisal reactions. The results from this model showed that distributive justice influenced satisfaction with performance ratings, and procedural justice influenced satisfaction with the appraisal system. Both distributive and procedural justice had more influence on satisfaction with appraisal feedback than components of interactional justice perceptions (Jawahar, 2007). His study was the first to imply that satisfaction with the system might influence satisfaction with feedback. Jawahar (2007) reported that the implications for practice highlighted the ratees' fairness perception with appraisal process satisfaction, the need to have procedures based on accurate information and a process for appealing.

Palaiologus et al. (2011) examined organisational justice and employee satisfaction in performance appraisal. The findings showed that the administrative purposes of performance appraisal were related to distributive justice and procedural justice, while the developmental purpose was related to interactional justice. The appraisal process was found to be positively related to the three justice dimensions and the relationship with procedural justice was stronger (Palaiologos et al., 2011). They observed that the employees felt that the performance appraisal process was fair when there was a clear criterion of evaluation that was known and understood by all the employees. The results showed a strong correlation between rating satisfaction and both distributive and procedural justice with rating satisfaction positively related to distributive justice (Palaiologos et al., 2011). This finding contradicts the research by Jawahar (2007), which showed that rating satisfaction is related only to distributive justice. The research also indicated that the supervisor's role played a significant part in the interactional justice, as they seem to be the basis of the satisfaction that employees receive through the performance appraisal system and thus the importance of appraiser training (Palaiologos et al., 2011). The relationship between interactional justice and feedback satisfaction was not confirmed, but a positive relationship was found between procedural justice and feedback satisfaction, confirming the research by Jawahar (2007).

Leader-member exchange (LMX) is a social exchange construct between organisational justice and the employee's work performance with the organisation's (or supervisor's) input in the relationship (Wang et al., 2010). A study was undertaken by Wang et al. (2010) on the impact of organisational justice on work performance. The results showed that when organisational commitment and LMX were used as mediators, the three justice dimensions generally did not have a direct effect on all work performance and that only interactional justice had a weak relationship with task performance. The direct relationship found in previous research was attributed to the use of incorrect mediators (Wang et al., 2010). With regard to the employee-supervisor relationship, performance may be related to interactional justice, where Chinese people tend to place more emphasis on interpersonal relationships, morality and emotion (Wang et al., 2010). The research suggests that employees who feel fairly treated had a positive effect on the organisation (Wang et al., 2010). The limitation of this research was that self-report data was used and that cultural factors influence attitudes and behaviours and thus need to be taken into consideration.

Ikramullah et al. (2011) studied the fairness perceptions of a performance appraisal system in two public sector organisations in Pakistan. Self-reporting questionnaires were distributed and 261 employees responded to the survey. The four justice dimensions were evaluated. The results showed that the employees perceived their appraisal process as fair as determined by the four justice dimensions (Ikramullah, et al., 2011). The findings also showed that the employees agreed (perceived as fair) with all the items of distributive justice and interpersonal justice (Ikramullah et al., 2011). Since these relate to outcome decisions and treatment by the supervisor, it is possible that supervisors who rate high do so to prevent conflict and tension between both parties, which may also be based on personal matters (like/dislike) (Ikramullah et al. , 2011). Responses from procedural justice for "setting performance targets" showed that employees neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement and showed inconsistency when setting the targets. This impacts on performance, as employees were not clear as to their targets (Ikramullah et al., 2011). A similar finding was made with "seeking appeal", where there was no process in place for employees to address their concerns with their supervisor during the review process (Ikramullah et al., 2011). The study showed where the discrepancies were in the system and how interpersonal relationships can affect the ratings. This study showed support for the four justice dimensions.

5 Research methodology

5.1 Purpose of research

The purpose of this research was to measure justice perceptions of performance management practices, using a theoretical foundation drawn from organisational justice theories to examine and recommend corrective actions and procedures to enhance the process and the ultimate success of the system in use.

5.2 Research objectives

The objective of this research was to examine the performance management practices in a company in the chemical industry, by identifying the prevalence of current performance management practices, using justice perception theories.

5.3 Research design

A cross-sectional quantitative survey design (Shaughnessy & Zechmeister, 1997) using primary data was used in this study. Primary data allows for the collection of data from the original source, although it is time consuming and sometimes costly. This design allows for the description of the population at a specific time and can, therefore, indicate the justice perceptions of performance management. This design is also suited to the development and validation of questionnaires (Shaughnessy & Zechmeister, 1997). The quantitative approach allows for the conceptualisation of constructs in accordance with specific measuring instruments and the utilisation of such instruments in the measurement of the constructs in a controlled and systematic manner (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000). In addition, the use of a quantitative approach adds to the reliability of the study as a fixed procedure is followed and can therefore be replicated (TerreBlanche, Durrheim & Painter, 2006).

5.4 Research procedure

Written clearance to conduct the research was obtained from the participating organisation. The target population included all the employees in the selected organisation. The employees were requested to participate in the research voluntarily by completing the questionnaires. All the employees were issued with the questionnaire and were requested to complete it, based on their most recent performance appraisal. A covering letter accompanied each questionnaire, stating the purpose of the research, guaranteeing the protection of their identity as this was an anonymous survey, and guaranteeing the confidentially of the information. The completed questionnaires were kept in a secure place. The raw data was captured and converted to a Statistica statistical package dataset.

A total of 140 questionnaires were issued to all the employees in the organisation who had undergone a performance appraisal. To assist with the collection of the completed questionnaires, a representative from each region was nominated by the manager of that region to arrange for the questionnaires to be sent by courier to the researcher. This was with the exception of one region where individuals personally delivered the completed questionnaires to the researcher. Completed surveys were received from 102 respondents, giving a response rate of 72 per cent, which is regarded as sufficient to ensure reliable data from the research study.

5.5 Measuring instrument

The format of the research undertaken by Thurston and McNall (2010) was followed to test and measure justice perceptions in the organisation according to the four justice dimensions of procedural justice, distributive justice, interpersonal justice and informational justice. The rationale for using a model was twofold: it ensured that all the relevant organisational areas were covered (French & Bell, 1984:199). According to authors such as Clark and Watson (1995), if an instrument development is modelled on recognised models and theories, the construct validity of the instrument improves. Furnham (1997) mentions the use of theoretical and conceptual models as a requirement for any scientific measurement. Fifty items formed the basis for the research to measure justice perceptions. The items were conceptualised from organisational justice and performance literature and from empirical research on justice perceptions and legal considerations in performance appraisal cases (Thurston & McNall, 2010). These items were sorted to create ten performance appraisal perceptual constructs based on the four justice dimensions of procedural, distributive, interpersonal and informational perceptions.

5.6 Reliability

The scale and sorting of the items were carried out by five subject matter experts who had experience as raters and who rated for completeness and sentence clarity (Thurston & McNall, 2010). The testing of inter-rater reliability was carried out on all 50 items with non-conformances clarified to achieve 100 per cent agreement (Thurston & McNall, 2010). Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated for each construct to determine scale reliability with alpha = 0.70 being the normal limits acceptable for decisions affecting groups (Thurston & McNall, 2010). The Cronbach alpha coefficient as reported by Thurston and McNall (2010) for each of the constructs ranged from a high of 0.93 to a low of 0.68. The construct "providing feedback" had the highest alpha coefficient of 0.93, and the construct "ratings not based on politics" had the lowest alpha coefficient value. The results for the constructs are reported in brackets. The ten performance appraisal perceptual constructs were "ratings not based on politics" (0.68), "setting criteria" (0.80), "seeking appeals" (0.86), "ratings based on equity" (0.87), "clarifying expectations" (0.87), "explaining and justifying decisions" (0.88), "assigning raters" (0.90), "raters show respect" (0.91), "raters show sensitivity" (0.92) and "providing feedback" (0.93).

5.7 Data analysis and technique

The statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistica statistical package. Descriptive statistics (e.g. means, skewness, standard deviation and kurtosis) were used to analyse the data. Pearson product-moment correlations were calculated to assess the direction and strength of the relationships between the variables. In order to counter the probability of a type I error, and the significance value was set at the 95 per cent confidence interval level (p < 0.05).

Cronbach's alpha coefficients and inter-item correlations were used to assess the internal consistency of the measuring instrument (Clark & Watson, 1995). Coefficient alpha conveys important information on the proportion of variance contained in a scale, while the inter-item correlation is an important index for supplying supplementary information about a scale. Inter-item correlations and confirmative factor analysis were used to determine the validity of the instrument.

T-tests and one-way analyses of variance were used to determine differences between the subgroups of the population. Post hoc tests (Sheffe) for variance width were carried out to determine whether groups differed significantly from each other if analyses of variance (ANOVA) are applied (Hair, Anderson, Tatham & Black, 1998). A cut-off point of 0.50 (medium effect) (Cohen, 1988) was set for the practical significance of differences between means. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were used to specify the relationships between the variables. A cut-off point of 0.30 (medium effect) (Cohen, 1988; Steyn, 1999) was set for the practical significance of correlation coefficients.

6 Research results

6.1 Profile of the respondents

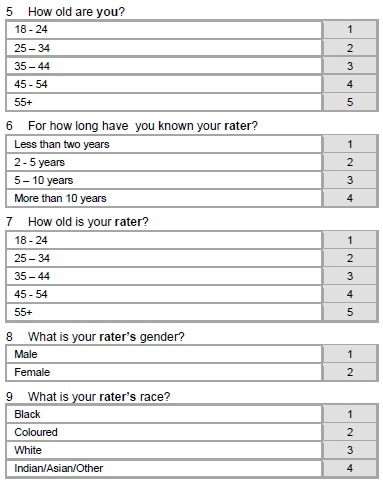

Completed surveys were received from 102 respondents, giving a response rate of 72 per cent. Of the respondents, 56 per cent were male, 60 per cent had more than 5 years of service in the organisation and 45 per cent were Black, 13 per cent were Coloured, 5 per cent Indian and 37 per cent White. The largest age groups were between the ages of 25 and 34 years and between 35 and 44 years, each with 33 per cent, with only 3 per cent of the respondents falling within the 18 to 24 year-old group and 24 per cent of the respondents falling within the 45 to 54 year-old group. Only 7 per cent of the respondents fell within the 55+ year-old group. A comparison the return rate to the demographics of the organisation showed that only 55 per cent of the Black race group responded, with a >95 per cent return rate from the other race groups. Employees were grouped according to their work functions and categorised into three departments. Those employees employed in the customer service department consisted of the organisation's internal and external sales people, employees grouped into the administration staff category were employees from the finance department, the IT department and general administration, while employees grouped into the supply chain category were employed in the warehouse. All the departments were well represented considering the number of people employed in the department by the organisation.

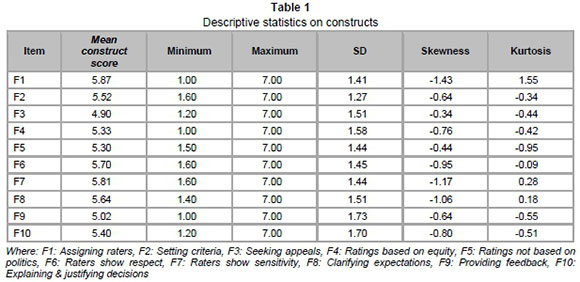

6.2 Descriptive statistics on constructs

An overall score was calculated for each construct based on grouping together the items that made up the construct (Thurston & McNall, 2010). The overall mean item score, the minimum, maximum, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis statistics for each construct are presented in Table 1. Only those items identified as falling outside of the critical values of 2.00 for skewness and 7.00 for kurtosis will be identified and discussed (West, Finch & Curran, 1995).

For procedural justice, which contained the constructs "assigning raters" (standard deviation, SD=1.41), "setting criteria" (SD=1.27) and "seeking appeals" (SD=1.57), the mean scores ranged from a high of 5.87 to a low of 4.90, indicating that respondents agreed the most with the construct of "assigning raters" and the least with "seeking appeals". This construct also had the highest mean score of all the constructs. The respondents scored a minimum value of 1.00 for "assigning raters" to a maximum of 7.00 for all the constructs in this justice dimension. For distributive justice, the constructs "ratings based on equity" (SD=1.58) and "ratings not based on politics" (SD=1.44) made up this justice dimension. The respondents rated both constructs similarly with mean scores of 5.33 and 5.30 respectively, showing that they agreed to the same extent with both constructs. "Ratings based on equity" had the lowest minimum score of 1.00, while both constructs had a maximum of 7.00. For interpersonal justice, the constructs "raters show respect" (SD=1.45) and "raters show sensitivity" (SD=1.44), the respondents' scoring suggested higher agreement with both constructs, as the mean scores were 5.70 and 5.81 respectively. This was supported by minimum values obtained of 1.6 for both constructs and both having a maximum of 7.00. The informational justice dimension consisted of "clarifying expectations" (SD=1.51), "providing feedback" (SD=1.73) and "explaining and justifying decisions" (SD=1.70). The construct "clarifying expectations" had the highest mean score of 5.64 of all the scales with "providing feedback" having the lowest mean score of 5.02. "Providing feedback" had the lowest minimum score of all the scales, with all three scales scoring a maximum of 7.00.

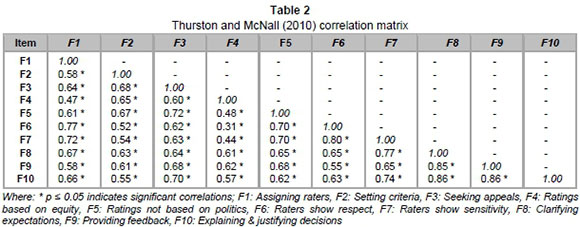

6.3 Correlation analysis

The correlation between the factors of the measuring instruments is reported in Table 2.

Table 2 reports that, if 0.5 is used as the cut-off point for medium effects (Cohen, 1998), then "assigning raters" has a positive relationship with "setting criteria" (0.58), "rating based on equity" (0.47), "seeking appeals" (0.64), "ratings not based on equity" (0.61), "raters show respect" (0.77), "raters show sensitivity" (0.72), "clarifying expectations" (0.67), "providing feedback" (0.58) and "justifying and explaining decisions" (0.66). "Setting criteria" has a positive relationship with "seeking appeals" (0.68), "ratings based on equity" (0.65), "ratings not based on politics" (0.67), "raters show respect" (0.52), "raters show sensitivity" (0.54), "clarifying expectations" (0.63), "providing feedback" (0.61) and "justifying and explaining decisions" (0.55). "Seeking appeals" has a positive relationship with "ratings based on equity" (0.60), "ratings not based on politics" (0.72), "raters show respect" (0.62), "raters show sensitivity" (0.63), "clarifying expectations" (0.64), "providing feedback" (0.68) and "justifying and explaining decisions" (0.70).

Ratings based on equity has a positive relationship with "ratings not based on politics" (0.48), "raters show respect" (0.31), "raters show sensitivity" (0.44), "clarifying expectations" (0.61), "providing feedback" (0.62) and "justifying and explaining decisions" (0.57). "Ratings not based on politics" has a positive relationship with "raters show respect" (0.70), "raters show sensitivity" (0.70), "clarifying expectations" (0.65), "providing feedback" (0.68) and "justifying and explaining decisions" (0.62). "Raters show respect" has a positive relationship with "raters show sensitivity" (0.80), "clarifying expectations" (0.65), "providing feedback" (0.55) and "justifying and explaining decisions" (0.63). "Raters show sensitivity" has a positive relationship with "clarifying expectations" (0.77), "providing feedback" (0.65) and "justifying and explaining decisions" (0.74). "Clarifying expectations" has a positive relationship with "providing feedback" (0.85) and "justifying and explaining decisions" (0.86).

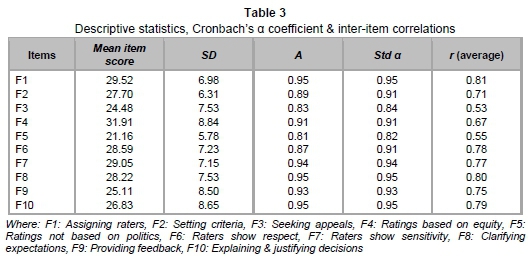

6.4 Descriptive statistics, Cronbach's α coefficient and inter-item correlations

Cronbach's alpha, which estimates test-score reliability from a single test administration based on test items internal to the test, is also referred to as an internal-consistency coefficient (Webb et al., 2006). This was used to determine how closely related the ten constructs are to one another. The results are presented in Table 3.

The mean item score indicates the level of agreement according to a seven-point Likert scale. With the exception of the construct "ratings not based on politics", where respondents recorded the lowest mean score of 21.16, the respondents agreed with the statements in the questionnaire.

The analysis returned two coefficients, raw and standardised alpha, where raw is based on item correlation and standardised is based on item covariance. Usually, the higher the alpha, the more reliable the test, with 0.7 and above being acceptable (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). The alpha and standardised alpha for "assigning raters" were 0.95 and 0.95 respectively, "setting criteria" were 0.89 and 0.91 respectively, "seeking appeals" were 0.83 and 0.84 respectively, "ratings on equity" were 0.91 and 0.91 respectively, "ratings not based on politics" were 0.81 and 0.82 respectively, "raters show respect" were 0.87 and 0.91 respectively, "raters show sensitivity" were 0.94 and 0.94 respectively, "clarifying expectations" were 0.95 and 0.95 respectively, "providing feedback" were 0.93 and 0.93 respectively and "justifying and explaining decisions" were 0,95 and 0.95 respectively. All reported values for the constructs had values of >0.8, indicating a high internal consistency of the items making up the construct of the scale.

6.5 Analyses of variance between groups

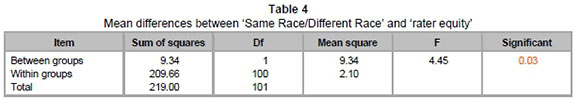

In order to determine whether there were significant differences between demographic variables and variables of constructs, post hoc tests (Sheffe) for variance width were carried out to determine whether groups differed significantly from one another if analyses of variance were applied. The results of the analysis of variance are shown in Table 4, for "same/different race groups" the independent variable and "ratings based on equity" as the dependent variable.

The results of the analyses of variance indicated that there was a significant difference between the groups (p=0.03) if "same/different race groups" was used as the grouping variable and the factor "ratings based on equity" as the dependent variable.

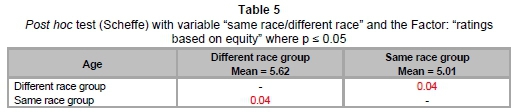

In Table 5, the results of the post hoc test (Sheffe) are reported. Only significant results are reported.

The model fit is significant for respondents from the "same/different race groups" and for the factor "ratings based on equity", as p < 0.05. The results show that the model variance of 9.34 between groups is considerably higher than within groups (2.10). A significant difference was identified between the different race groups with a mean average score of 5.62 and the same race groups with a mean score of 5.01.

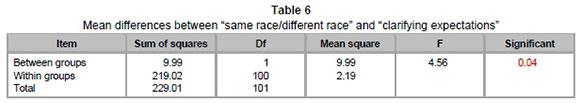

The results of the analysis of variance are shown in Table 6 for "same/different race groups" (the independent variable) and "clarifying expectations" as the dependent variable.

The analyses of variance indicated that there is a significant difference between the groups (p=0.03) if "same/different race groups" is used as the grouping variable and the factor, "clarifying expectations" as the dependent variable.

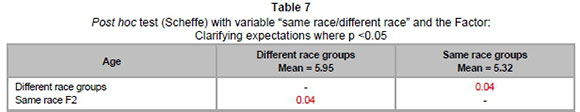

In Table 7, the results of the post hoc test (Sheffe) are reported. Only significant results are reported.

The model fit is significant for respondents from the "same/different race groups" and for the factor "clarifying expectations", as p < 0.05. The results show that the model variance of 9.99 between groups is considerably higher than within groups (2.19). A significant difference was identified between the different race groups with a mean average score of 5.95 and the same race groups with a mean score of 5.32.

7 Discussion of results

Past research has shown that employees use their experience and interaction with their managers to determine whether they are being treated fairly or not. These perceptions affect their behaviour in the organisation, ultimately influencing the attainment of the strategic goals of the organisation. The literature review revealed that the appraisal process is related to the social environment under which the employee operates (Zheng et al., 2012; Marjani & Ardahaey, 2012), and that the system in place cannot be blamed if there is no management commitment to make the process work (Chen & Eldridge, 2010). Without set objectives, employees have no clear direction as to what to achieve, which makes the appraisal process biased, creating negative perceptions of the process (Ikramullah et al., 2011). It also highlights the influence managers have on employees' perceptions (Heslin & VandeWalle, 2009), the role of raters and rater accountability (Payne et al., 2009), for employees to be able to seek the justification of decisions (Thurston & McNall, 2010) and how favourable perceptions lead to employees' positive outlook and organisational commitment (Pulakos & O'Leary, 2011). The results from the study show that, overall, the respondents viewed the performance management process positively. On average, the perceptions of performance management practices for all ten scales were greater than 4, the neutral point of the scale.

The results from this research for scale reliability were compared with those obtained by Thurston and McNall (2010). The analysis showed that the reliability of all ten scales in this research reflected an α >0.8, indicating a high internal consistency of the items in the scale. The results complemented the results obtained by Thurston and McNall (2010) where they reported that nine scales exceeded the normal limits of α = 0.7; the scale measuring "absence of politics" had an internal consistency measure of α = 0.68 which is the minimal acceptable level (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). This scale also had a lowest value of α = 0.82, followed by "seeking appeals" with α = 0.84.

The ten constructs provided a foundation in helping to understand the attitudes and perceptions of the respondents regarding the performance management systems. As Thurston and McNall (2010) pointed out, the constructs demonstrated good psychometric properties for the items making up the constructs and confirmed that the operational definitions of the construct correlate with other constructs in predictable ways. The findings from the study for the analysis of variance indicate that respondents within the 18 - 24-year old age group scored the "assigning of raters" slightly above neutral, the actual score being 4.33, indicating that perhaps management needs to review the assignment of raters to this group or the approach used by the raters for this group of respondents.

The results of the analysis of variance for "age of rater" and the "rater explaining and justifying decisions" showed that respondents within the 45 - 54-year old group had a score of 4.33, indicating that this group felt that the raters did not adequately explain and/or justify their decisions. Research in social psychology indicates that younger and older employees have different expectations regarding work and this may impact on their work performance. Older employees are likely to focus on procedural justice, as they focus on feelings of personal importance, and younger employees emphasise distributive justice owing to their need for economic security and success (Nasurdin & Khuan, 2011). The results of the analysis of variance for respondents from the different departments and setting criteria showed that the Customer Service Department was most satisfied with the construct of setting criteria, scoring a mean average of 6.03. This department is responsible for sales so careful attention is possibly given to the criteria set for this department with incentives that motivate this team to achieve higher performance. The analysis of variance for respondents from the different race groups and ratings based on equity showed that the Black race group was most satisfied, scoring a mean average of 5.80, while the White race group and Indian race group scored slightly above 4, the neutral point of the scale, with 4.73 and 4.64 respectively. These results were confirmed when analysis between rater/ratee and same/different race group for ratings based on equity showed that there were variations in ratings.

A similar observation was made between rater/ratee, same/different race and clarifying expectation, where the same race group reported a lower mean average score, compared to the different race groups that reported a higher mean average score. The overall results of this study therefore confirm the previous work done by Thurston and McNall (2010) regarding the four justice dimensions, the scales making up the ten constructs and the internal consistency of the items within the scale.

8 Conclusion

The results of this study have confirmed the study undertaken by Thurston and McNall (2010) where the ten constructs (assigning raters, setting criteria, seeking appeals, ratings based on equity, ratings not based on politics, raters show respect, raters show sensitivity, clarifying expectations, providing feedback and explaining and justifying decisions) demonstrated good psychometric properties for the items making up the constructs. The measuring instrument used was modelled on recognised models and theories, and this study contributes to it by improving the construct validity of the instrument (Clark & Watson, 1995). The analysis showed that the reliability of all ten scales in this research had α >0.8, indicating a high internal consistency of the items in the scale. The study also verifies the research by Ikramullah et al. (2011), St-Onge, Morin, Bellehumeur & Dupius (2009), and Tuytens and Devos (2012), in that employee justice perceptions relating to performance management practices may be explained using organisational justice theories according to the four justice dimensions of procedural, distributive, interactional and informational justice. If employees are more motivated when they perceive their performance appraisals as fair and trustworthy (Froydis, Marnburg & Furunes, 2010; Chen & Eldridge, 2010; Davila & Elvira, 2009; Day, 2011) then ensuring the processes and ensuring that the outcomes from the process are seen as fair can lead to improved organisational performance (Ikramullah et al., 2011).

The findings of the study contribute valuable new knowledge to the field of psychology and may be used by human resource management to implement procedures that will fully engage all concerned in performance management practices. Performance appraisal is no longer viewed simplistically as a means of recording and reporting an employee's performance but is seen as a more strategic and holistic approach to linking the organisation's strategic plan with individual performance (Chen & Eldridge, 2010).

9 Recommendations

This is the first study undertaken at this organisation to determine employees' perceptions of its performance management practices. A standardised performance appraisal system is used throughout the organisation that is fully supported by the senior management team. The success of the process and procedures in place depends on having a fully integrated system that all employees can trust and whereby their contributions are seen and acted upon in a fair and transparent manner. A formal process allowing employees to seek appeals should be implemented that will help improve justice perceptions as well as relations between employees and managers. Secondly, the organisation must ensure that all the employees are treated fairly by their managers during the appraisal process and that the managers are seen as being sensitive and willing to make time to ensure employees' concerns are properly addressed. Employees in the customer service department were most satisfied with their setting criteria compared to the other departments, implying that management should follow a similar example for the other two departments. Management should also ensure that the employees have the necessary skills, resources, knowledge and understanding so they can develop a sense of adequacy, self-confidence and competency. Processes and systems that are regarded favourably by employees will result in positive perceptions of the organisational climate, and help create a sense of harmony and a willingness in all employees to work in a reciprocal fashion to the benefit of all.

10 Limitations and suggestions for future study

The study has the following limitations which should be taken into account. The organisation studied is a private entity operating within the chemical industry sector and may be associated with certain unique characteristics, such as having a workforce that is not unionised. Therefore the findings may not be generalised to public organisations or industries outside this sector. Extending the sample size as well as incorporating other sectors would further help support the four justice dimensions and make-up of the constructs.

Because a cross-sectional design was employed, no causal relationship between the variables could be determined over a period of time. The causal relationship was interpreted at a specific point in time and not over a period. The study methodology employed a questionnaire and hence required self-reporting. As self-reported data may be subjected to common method bias owing to the measurement method (Chen & Eldridge 2011), alternate methods should be employed, such as interviews and/or mixed method research or the data should be verified using objective criteria. Extending the study to other companies or other industry sectors, using a sampling strategy could result in better representation, allowing for more accurate and generalised deductions to be made.

This study only evaluated the responses from the employees' perspective, thereby restricting the identification of other variables that may have influenced the performance outcome, for example, input from the raters. Since trust has been found to affect the way employees respond to performance management, future research should include this dimension as a way of explaining performance outcomes. Since raters are accountable to the employees they rate and to their supervisor, future research should include rater feedback and accountability, to allow insight into the performance management process. Moreover, justice perceptions reach further into the organisation and do not stop at organisational and individual level, and may also be associated with the co-worker relationship, which may be another dimension for future study.

References

AGGARWAL-GUPTA, M. & KUMAR, R. 2010. Look who's talking! Impact of communication relationship satisfaction on justice perceptions. Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers, 35(3):55-65. [ Links ]

AL-ZU'BI, H.A. 2010. A study of relationship between organisational justice and job satisfaction. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(12):102-110. [ Links ]

BAIRD, K., SCHOCH, H.M. & CHEN, Q. 2012. Performance management system effectiveness in Australian local government. Pacific Accounting Review, 24(2):161-185. [ Links ]

BLUME, B.D., BALDWIN, T.T. & RUBIN, R.S. 2009. Reactions to different types of forced distribution performance evaluation systems. Journal of Business Psychology, 24:77-91. [ Links ]

BROWN, M., HYATT, D. & BENSON, J. 2010. Consequences of the performance appraisal experience. Personnel Review, 39(2):375-396. [ Links ]

CHEN, J. & ELDRIDGE, D. 2010. Are "standardized performance appraisal practices" really preferred? A case study in China. Chinese Management Studies, 4(3):244-257. [ Links ]

CLARK, L.A. & WATSON, D. 1995. Construct validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7:309-319. [ Links ]

COHEN, J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.) Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum & Associates. [ Links ]

COLQUITT, J.A. & RODELL, J.B. 2011. Justice, trust, trustworthiness: A longitudinal analysis integrating three theoretical perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, (6):1183-1206. [ Links ]

DAY, N.E. 2011. Perceived pay communication, justice and pay satisfaction. Employee Relations, 33(5): 476-497. [ Links ]

DAVILA, A. & ELVIRA, M.M. 2009. Psychological contracts and performance management in Mexico. International Journal of Manpower, 28(5):384-402. [ Links ]

FARNDALE, E., HOPE-HAILEY, V. & KELLIHER, C. 2011. High commitment performance management: The roles of justice and trust. Personnel Review, 40(1):1-20. [ Links ]

FRENCH, W.L. & BELL, C.H. 1984. Organizational development: Behavioral science interventions for organizational improvement (3rd ed.) Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

FROYDIS F, MARNBURG, E. & FURUNES, T. 2010. Employees' perceptions of justice in performance appraisals. Nursing Management - UK, 17(2):30-34. [ Links ]

FURNHAM, A. 1997. The psychology of work behaviour. Howe: Psychology Press. [ Links ]

GEETA, R., POOJA, G. & RENU, R. 2011. Effect of justice perception on managerial effectiveness. IUP Journal of Organisational Behavior, 10(2):7-20. [ Links ]

HAIR, F.F., ANDERSON, R.E., TATHAM, R.L. & BLACK, W.C. 1998. Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

HAUSKNECHT, J.P., STURMAN, M.C. & ROBERSON, Q.M. 2011. Justice as a dynamic construct: Effects of individual trajectories on distal work outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4):872-880. [ Links ]

HESLIN, P.A. & VANDEWALLE, D. 2009. Performance appraisal procedural justice: The role of a manager's implicit person theory. Journal of Management, 37: 1-25. [ Links ]

IKRAMULLAH, M., SHAH, B., UL HASSAN, F.S., ZAMAN, T. & KHAN, H. 2011. Fairness perceptions of performance appraisal system: An empirical study of civil servants in district Dera Ismail Khan, Pakistan. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(21):92-100. [ Links ]

JAWAHAR, I.M. 2007. The influence of perceptions of fairness on performance appraisal reactions. Journal of Labor Research, 28(4):735-754. [ Links ]

KERLINGER, F.N. & LEE, H.B. 2000. Foundations of behavioural research (4th ed.) USA: Harcourt College Publishers. Fort Worth, Texas. [ Links ]

KONDRASUK, J.N. 2011. So what would an ideal performance appraisal look like? Journal of Applied Business and Economics, 12(1):57-71. [ Links ]

MARJANI, A.B. & ARDAHAEY, F.T. 2012. The relationship between organisational structure and organisational justice. Journal of Asian Social Science, 8(4):124-130. [ Links ]

MURPHY, K.R. 2008. Explaining the weak relationship between job performance and ratings of job performance. Industrial and Organisational Psychology, 1:148-160. [ Links ]

NASURDIN, A.M. & KHUAN, S.L. 2011. Organisation justice, age and performance connection in Malaysia. International Journal of Commerce & Management, 21(3):273-290. [ Links ]

NUNNALLY, J. C. & BERNSTEIN, I. H. 1994. Psychometric theory (3rd ed.) NY: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

PALAIOLOGOS, A., PAPAZEKOS, P. & PANAYOTOPOULO, L. 2011. Organisational justice & employee satisfaction in performance appraisal. Journal of European Industrial Training, 35(8):826-840. [ Links ]

PAYNE, S.C., HORNER, M. T., BOSWELL, W.R., SCHROEDER, A.N. & STINE-CHEYNE, K.J. 2009. Comparison of online and traditional performance appraisal systems. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(6):526-544. [ Links ]

PULAKOS, E.D. & O'LEARY, R.S. 2011. Why is performance management broken? Industrial and Organisational Psychology, 4:146-164. [ Links ]

ROWLAND, C.A. & HALL, R.D. 2012. Organisational justice and performance: Is appraisal fair? EuroMed Journal of Business, 7(3):280-293. [ Links ]

SHAUGHNESSY, J.J. & ZECHMEISTER, E.B. 1997. Research methods in psychology (4th ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

SIMMONS, S. 2008. Employee significance within stakeholder-accountable performance management systems. The TMQ Journal, 20(5):463-475. [ Links ]

STEYN, H.S. 1999. Praktiese betekenisvolheid. Die gebruik van effekgroottes. Wetenskaplike Bydraes -Reeks B: Natuurwetenskappe Nr. 117. Potchefstroom: PU vir CHO. [ Links ]

ST-ONGE, S., MORIN, D., BELLEHUMEUR, M. & DUPIUS, F. 2009. Managers' motivation to evaluate subordinate performance, qualitative research in organisations and management. An International Journal, 4(3):273-293. [ Links ]

TERREBLANCHE, M., DURRHEIM, K. & PAINTER, D. 2006. Research in practice: applied methods for the social sciences (2nd ed.) Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

THURSTON J.R, P.W. & MCNALL, L. 2010. Justice perceptions of performance appraisal practices. Journal of Management Psychology, 25(3):201-228. [ Links ]

TUYTENS, M. & DEVOS, G. 2012. Importance of system and leadership in performance appraisal. Personnel Review, 41(6):756-776. [ Links ]

WANG, K.Y. & NAYIR, D.Z. 2010. Procedural justice, participation and power distance: Information sharing in Chinese firms. Management Research Review, 33(1):66-78. [ Links ]

WANG, X., LIAO, J., XIA, D. & CHANG, T. 2010. The impact of organisational justice on work performance: Mediating effects of organisational commitment and leader-member exchange. International Journal of Manpower, 31(6):660-677. [ Links ]

WEBB, N.M., SHAVELSON, R.J. & HAERTEL, E.H. 2006. Handbook of statistics. [online], Vol 26. Elsevier B.V. Available at: <http://www.stanford.edu/dept/SUSE/SEAL/Reports_Papers/ReliabCoefsGTheoryHdbk.pdf> [accessed 2012-12-28]. [ Links ]

WEST, S.G., FINCH, J.F. & CURRAN, P.J. 1995. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. Published an R.H. Hoyle (ed.) Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 65-75). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

ZHENG, W., ZHANG, M. & LI, H. 2012. Performance appraisal process and organisational citizenship behavior. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(7):732-752. [ Links ]

Accepted: July 2015

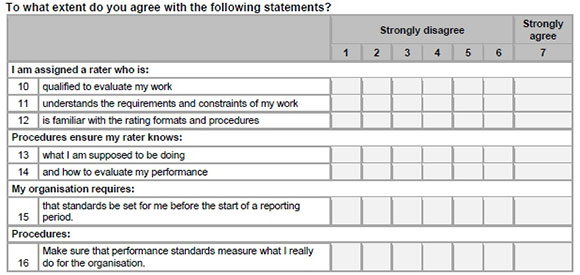

Appendix 1: Questionnaire

Introduction:

Thank you for taking the time to answer this questionnaire. This questionnaire forms part of a thesis that will contribute towards UNISA's MBL degree. The research is focused on performance management practices in the Chemical industry environment. Data is being collected with the aim of customising a tool that will be able to track and identity issues within the systems and processes that are employed.

Results obtained from the survey will be kept confidential and neither the respondent's name nor the organisation's name will be given to any 3rd party. In keeping with this, no contact details, such as name, phone number or email address is required on the enclosed questionnaire.

Please answer the following questions by marking the appropriate box:

Below is a series of questions relating to various aspects of performance appraisal. Each question has seven (7) possible answers. Please mark the number which best expresses the extent to which the statement is applicable to you. Note that numbers 1 and 7 are the extreme answers, while number 4 means that both statements are equally applicable to you. If the words under 1 are right for you, draw a cross (x) over number 1; if the words under 7 are right for you, draw a cross (x) over number 7. If you feel differently, cross (x) the number which best expresses your feeling. Please give only one answer to each question.