Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versión On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.18 no.3 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2222-3436/2015/V18N3A4

ARTICLES

Institutional forces and divestment performance of South African conglomerates: Case study evidence

David KingI; David ColdwellII; Tasneem JoosubIII; David McClellandIV

ICollege of Business, Iowa State University

IISchool of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

IIISchool of Accountancy, University of the Witwatersrand

IVSchool of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

ABSTRACT

The history of South Africa serves as a natural experiment in how a changing institutional environment impacts corporate structure. Based on institutional theory, we anticipate higher performance through emulating successful strategies or through restructuring consistent with mimetic isomorphism. Conversely, coercive isomorphism results from restructuring driven by regulation, and we anticipate that they are associated with lower performance. To examine these relationships, we consider divestment by South African firms over two periods, using mixed methods. We find tentative support for our predictions, and we outline implications for policymakers, as well as for management research and practice.

Key words: divestment, institutional theory, coercive and mimetic isomorphism, event analysis, case studies

1 Introduction

Acquisitions are more likely to occur in dynamic environments (see, e.g., Heeley, King & Covin, 2006). The competitive environment surrounding acquisitions has largely been excluded from research (Keil, Laamanen & McGrath, 2013). Further, acquisitions and divestment activity are related, as both involve the restructuring of firms (Capron, Mitchell & Swaminathan, 2001), but there is less research on divestment than acquisitions (Villalonga & McGahan, 2005; Xia & Li, 2013). Both acquisitions and divestment transfer control of corporate assets, and we define divestment as a firm adjusting its ownership and business profile by way of spin-off, unbundling, equity carve-out, split-up or unit sell-off (Brauer, 2006).

Understanding the rationale of, and performance implications for, corporate restructuring is fundamental to strategy. Available research largely focuses on performance implications, and meta-analyses show that acquisitions have an insignificant, but slightly negative, impact on stock performance (King et al., 2004), with stock market reactions to divestment announcements being generally significant and positive (Lee & Madhavan, 2010). For example, after ITT announced that the conglomerate would split into three parts, its stock price jumped 17 per cent (Hagerty & Chon, 2011). Still, the reactions to divestiture announcements are not always positive (Sanders, 2001), with spin-offs motivated by regulatory problems experiencing negative shareholder returns (Hite & Owers, 1983). We extend this research to examine the impact of changes to institutional environments on corporate structure and shareholder performance. We further explore the impact of divestment on shareholder returns using a small sample of South African firms.

Research recognises that firms are embedded in an institutional environment that directly (i.e. through regulations) and indirectly (i.e. through subsidies) influences firms (Capron & Guillen, 2009; Hillman, Zardkoohi & Bierman, 1999; Porter, 1980). However, there is little research that examines the impact of social movements (Schneiberg & Lounsbury, 2008) and government influence on firm-value (Firth, Gong & Shan, 2013). Specifically, in a comprehensive review of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) literature across disciplines, Haleblian and colleagues (2009:485) found no research that directly examined the impact of regulatory change on acquisition performance. Meanwhile, Porter (1980:29-30) contends that the analysis of a firm's environment is incomplete without considering government policy and trends that impact competition. By extension, the influence of institutional forces on corporate structuring decisions represents a research lacuna that needs to be addressed.

The goal of this research project is to begin to address this shortcoming by examining the performance impacts of the changing institutional environment of South Africa on corporate divestment. Focusing on South Africa offers the advantage of a single setting to control for institutional differences among nations at the same time that South Africa became more consistent in its compliance with international norms. South Africa has also experienced widespread social change that has impacted the lives of its people and the corporations serving them. The end of apartheid with democratic elections in 1994 and subsequent changes in government policy with the promulgation of the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) Act of 2003 represent clear shifts in the institutional environment that allow a natural experiment in order to examine both the removal and subsequent imposition of constraints on corporate structuring. The 72 days of events in 1994 that included strikes and police opening fire on crowds outline how close the country came to civil war (SouthAfrica.info, 2013). Following the peaceful transition to democracy, the BBBEE Act of 2003 was designed to address widespread disparity in economic wealth reflected in a poverty rate of 38 per cent in 2000 (World Bank, 2013).

While improvements have been made, progress remains uneven. In 2012, disenchantment with the African National Congress (ANC) government led to the return of mass protests and the most violent clashes between police and striking workers since the end of apartheid (McGroarty & Maylie, 2012). The experience of South Africa has relevance, as do the social movements in the Middle East, termed the "Arab Spring", that evolved when Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tansian fruit seller, set himself on fire after being harassed by police on 10 December 2010 (De Soto, 2013). Moreover, unrest in the Ukraine in 2014 led to the end of President Viktor Yamukovych's government (Herszenhorn, 2014). Social movements shape governments and, in turn, governments shape the institutional environment for business. Understanding the circumstances of South Africa offers insights on how social movements and resulting institutional environments influence corporate structure.

2 Theory and exploratory propositions

Multiple theories can be used to explain divestiture (Lee & Madhavan, 2010; Moschieri & Mair, 2008; Xia & Li, 2013). However, we focus on the institutional environment as influenced by social movements (Davis & Thompson, 1994). Discontent can reach sufficient levels such that it culminates in collective action which drives change in the political environment with a view to regaining legitimacy (Davis & Thompson, 1994; McAdam, 1982). Legitimatisation involves an implicit process that applies expectations of the surrounding society (Johnson, Dowd & Redgeway, 2006). This relates to institutional isomorphism or to social, economic and cultural processes that lead organisations to adopt similar structures through coercive, mimetic and normative processes (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983).

The three mechanisms overlap to some extent, but their general emphasis relates to political influence and to the problem of legitimacy (coercive), standard responses to uncertainty (mimetic) and professionalisation (normative; Mizruchi & Fein, 1999). More specifically, coercive isomorphism relates to formal and informal pressures as a result of the legal and cultural expectations of the society in which an organisation operates that influence organisational behaviour and structure. This also relates to regulative legitimacy that defines what is legal or procedurally acceptable (Scott, 1995). An example is that of government environmental regulations designed to reduce pollution (Porter & Van der Linde, 1995). Such regulations are relevant to changes in corporate structure, as indirect evidence suggests that regulations shift the bidder-target power relationship in acquisitions (Haleblian et al., 2009). Meanwhile, mimetic isomorphism results from organisations modelling themselves on other organisations when there is environmental uncertainty. This relates to the cognitive legitimacy of comparable organisations providing templates for what is acceptable (Scott, 1995). For example, uncertainty resulting from weak emerging-market institutions has resulted in the formation of diversified business groups across different nations (Carney et al, 2011; Khanna & Palepu, 2000). Finally, normative isomorphism and legitimacy result from professional networks and/or formal education (Scott, 1995).

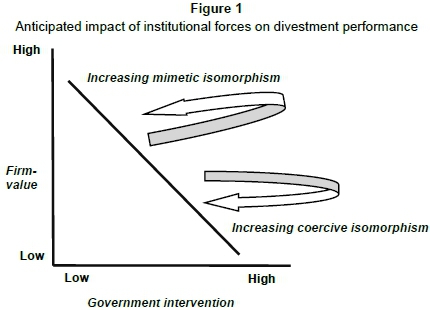

We hold that the institutional environment influences corporate-structure decisions through mimetic responses to uncertainly and regulatory (coercive) intervention, and we develop hypotheses within South Africa. In considering the impact of institutional forces on divestment, we anticipate that fewer (greater) restrictions on corporate structure will improve (lower) efficiency and firm-value (see Figure 1). The supporting logic behind these relationships is developed in the following sections for two time periods in South Africa's history.

3 Apartheid and post-apartheid period

The cultural environment of South Africa has influenced the corporate structure of domestic firms. Under apartheid, South Africa exhibited stark contrasts where racial classification determined socio-economic privilege. This led to a government state of emergency intended to suppress social unrest from 1984 to 1990 when negotiations for change began (Moller, 1998). This contributed to international sanctions that isolated South African corporations from international markets (Bhana, 2006; Kantor, 2001; Rossouw, 1997). Reduced competition enabled several South African firms to dominate the local market, with South African Breweries (SAB) commanding 98 per cent of the beer market (Bhana, 2000) and only six companies representing 80 per cent of the market capitalisation on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) by 1992 (Rossouw, 1997). During apartheid, and due to strict exchange controls and sanctions, South African corporations had few investment alternatives other than to acquire non-core business entities in South Africa (Hattingh, 2007; Rossouw, 1997). Since access to international markets was curtailed, conglomerates dominated the JSE (Castle & Kantor, 2000).

The dismantling of apartheid began in February 1990 when Nelson Mandela was released from prison. The reform process was endorsed in a whites-only referendum in 1992, and the first democratic elections were held in South Africa in April 1994. In 1994, South Africa exhibited among the worst national inequities in respect of income distribution, and that trend has persisted (Moller, 1998). However, democratic elections coincided with the end of sanctions, allowing South African corporations to rejoin the international business community and making divestment attractive (Bhana, 2004; Hattingh, 2007; Rossouw, 1997). The relief of having avoided civil war and the euphoria generated by Nelson Mandela's leadership were felt across South Africa. The promise of change was reinforced by the opening up of South Africa to international business and renewed foreign direct investment by Germany and the United States (US) that corresponded with a surge in M&A activity (Sapa, 2000; Radebe, 1998). At the same time, this period involved considerable uncertainty or conditions consistent with firms looking externally for cues on viable choices (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Geletkanycz & Hambrick, 1997).

South African corporations began unbundling previously acquired non-core businesses for reasons similar to those of their international counterparts. For example, the fourth merger wave occurred in the 1980s and it resulted in more specialised firms (Haleblian et al., 2009), and these divestments were recent, visible and successful or related to conditions with increased mimetic imitation (O'Neill, Pouder & Buchholtz, 1998). Another reason for its spread was the ability of South African corporations to receive a dual listing on an international stock exchange, something that sanctions restricted during apartheid (Bhana, 2000; Gostner, 2002; Walters & Prinsloo, 2002; Rossouw, 1997; Castle & Kantor, 2000), as South African corporations often had to unbundle in order to gain a foreign listing (De Jong, Rosenthal & Van Dijk, 2009). For example, AngloGold's listing on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in 1998 was a source of pride. The firm's CEO, Bobby Godsell, worked closely with the ANC government and he appointed members of previously underrepresented groups to leadership positions within the company in a precursor to what later became policy (AngloGold, 2007; NYSE, 2013). This reaction provided further motivation for other South African firms to initiate unbundling.

There were costs and benefits of a dual listing. On the one hand, there were the costs of restructuring operations. On the other, research indicated that the benefits of increased access to capital outweighed the costs (Bhana, 2000; Walters & Prinsloo, 2002). Additionally, divestment enabled South African firms to better compete in the new institutional environment by becoming more focused (Rossouw, 1997). Consistent with mimetic isomorphism, Hagel and Singer (2000) and Rossouw (1997) suggest that, as unbundling becomes more common, corporations are pressured to following suit and make a definitive decision about their core-business focus. For example, Hattingh (2007), Rossouw (1997), Kantor (2001) and Bhana (2006) found that, after 1994, political change in South Africa spurred on the divestment of non-core divisions, and, subsequently, conglomerate unbundling in South Africa became increasingly frequent (Correia et al., 2011).

While divestment involves costs (Hite & Owers, 1983), there are multiple reasons to expect performance improvement from divestment, as firms may diversify beyond the marginal benefits provided by related businesses and spin-offs may reduce information asymmetry and associated monitoring costs (Berger & Ofek, 1995; Lee & Madhavan, 2010). In a meta-analysis, business group formation was found to have a negative impact on firm-performance (Carney et al., 2011), suggesting that the unbundling of business groups creates value. In a less diversified firm, performance may improve as a result of greater group identification or social identity (cf. Huy, 2013; Kusstatscher & Cooper, 2005). There is also the anticipation that voluntary divestment is more likely to increase performance (Moschieri & Mair, 2008). Therefore, we propose:

Proposition 1: Divestment resulting from mimetic isomorphism behaviour increases shareholder value.

3.1 Period of government intervention

Black economic empowerment (BEE) provided further stimulus for the unbundling of South African conglomerates (Kantor, 2001; Correia et al., 2011). Conceived as a socio-economic process to bring about economic transformation by increasing the number of black people owning businesses, the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act 53 of 2003 (BEE Act) made the empowerment of previously disadvantaged groups an imperative (Mondi, 2009). This impacted multiple areas of business, with BEE scores considering ownership, management control, employee equity, and socio-economic development. It directly impacted corporate structure by enabling BEE points to be gained through ownership transfer of business assets (Bhana, 2006), and it represented a more coercive approach in the unbundling of South African businesses. It is also important to note that government pressure to restructure is not limited to South Africa. For example, upon realising the size of Merrill Lynch losses in 2008, Bank of America executives came under US government pressure to complete the acquisition (Fitzpatrick & Lublin, 2009). Additionally, government regulation of mining, including the imposition of windfall taxes by Australia and other governments, has reduced industry development (Kiernan, 2013).

Government pressure to further unbundle firms can be expected to result in lower performance, for several reasons. First and foremost, corporate unbundling was already occurring and it is reasonable to expect that firms' managers unbundled non-core activities that were likely to improve overall performance first. Additionally, coercion to sell business units likely results in lower prices. If motivated by obtaining BEE points, then buyers are restricted to qualifying groups, suggesting lower prices that are comparable with forced sales. For example, forced sales in bankruptcy result in an average 45 per cent price discount (Jory & Madura, 2009). Further, forced divestiture may suffer from a lack of planning that can hurt performance (Moschieri, 2011).

The lack of planning is evident from what happened to many South African divested businesses. For example, Anglo divested mining businesses following BEE, and one of the mines, Pamodzi 5, was closed due to the new owner lacking funds to maintain the mineshafts, leading to 200 former employees living in squalor in the firm's abandoned buildings (Mathews & Maqutu, 2013). Beneficiaries in other BEE transactions experienced similar problems, problems that were compounded by the 2008 financial crisis which hurt share prices and identified problems in divested firms to service debt due to low levels of initial capital (Mondi, 2009). Therefore, we put forward the following proposition:

Proposition 2: Divestment resulting from coercive isomorphic behaviour decreases shareholder value.

3.2 Methods

Divestitures require less public disclosure than acquisitions (Brauer & Wiersman, 2012), so we reviewed other published research and news archives to identify businesses divested by South African firms during two time periods: 1) during the dismantling of apartheid (1996-2002), and 2) at the time of government regulation by way of the BEE Act (2003-2011). We were able to identify 17 companies that divested businesses during the first period (1996-2002) and 25 companies that divested businesses during the second period (2003-2011) (see Appendix). The small sample size, incomplete disclosure for variables of interest, and the paucity of empirical data of rationale for actual firm-behaviour precluded traditional statistical analysis alone as a satisfactory method of analysis. For example, mimetic isomorphism for divestiture remained after the addition of government pressure to divest. Therefore, we concluded that an analysis of statistical data based on divestment by the selected firms into two main time periods was not sufficient that and a triangulation strategy using multiple forms of analysis together was needed (Creswell, 2003). This choice is also consistent with calls for more fine-grained analysis in divestment research (Moschieri & Mair, 2008). Based on news releases, we selected two companies from each period where mimetic and isomorphic forces could be more carefully compared through the adoption of a case study-type exploratory analysis. Yin (1994:13) defines a case study as "an empirical enquiry that: 1. Investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real life context, especially when, 2. The boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident".

The case study-approach helps to obtain data from real examples, as well as to determine commonalities in steps taken by companies to respond to a situation. Multiple cases were used to increase the external validity of the conclusions (Voss et al., 2002). In studying multiple cases, an important issue to consider is the selection of cases that enables replication. Yin (1994:46) states that case selection allows either the prediction of similar results (literal replication) or the production of contrasting results for predictable reasons (theoretical replication). Replication logic is used in this research, with each case selected on the basis of variables assumed to influence the degree of formalisation (Meredith, 1998). In this instance, all cases were selected on the basis of them being South African companies reacting to environmental changes that required managerial responses. Four cases were selected due to the availability of data that enabled the classification of a divestment event as the "ideal type" for mimetic or coercive isomorphism. The ideal type, originally developed by Max Weber, can be employed as a useful tool for comparative analysis and for the identification of ideal characteristics (Morrison, 2006). The ideal type, which is a construct used for data analysis and for systematic comparative analysis of historical data, was analysed on a case-by-case basis. The aim was to generate an ideally typical model consisting of the most prominent and important characteristics of a specific phenomenon. Before selecting ideal types, we identified 18 divestments by South African conglomerates in the first period, and 23 in the second period. Preliminary statistical analysis (see Appendix) showed that our sample and the available secondary data were not sufficient for cross-sectional analysis.

3.3 Performance

We measured performance of a divestment based on market reactions to divestment announcements. Share prices for selected firms were collected from 120 days prior to the event (90 days' estimation and 30 days of window) and a further 30 days after the event. There are 60 observations of share price values for each firm and day zero represents the day a divestment was announced. Thus observations constituting the estimation period are -120 to -30 with day -30 to day 30 used as the event window. In the market model, the normal returns for firm i on day t are calculated using the following formula: Rit = ai + ßi Rmt + εit where α and β are regression intercept and slope estimates, respectively, obtained from an ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression model, and by specifying the daily return as the dependent variable and the All-Share Index (ALSI) as the independent market proxy index. Alpha and β model parameters were captured for each firm and used to calculate the normal returns (returns that might have been expected had the divestment not occurred). The abnormal returns (AR) for each firm were then calculated by subtracting the normal returns from the actual returns for every day in the event period. This abnormal return was aggregated to produce a cumulative abnormal return (CAR) for each firm that represents the most common measure in divestment research (Moschieri & Mair, 2008).

3.4 Results

3.4.1 Period 1 (1996-2002)

Standard Bank and Growthpoint were identified as two firms that made divestments when the advent of democratic government led to the removal of restrictions on corporate structure. These two would serve as case studies for further analyses. The management decision to divest corresponded to "mimetic isomorphism" of successful international strategies (Afshar, Taffler & Sudarsanam, 1991) as revealed in the announcements of these two companies, and this was the main reason for their selection for investigation. South African corporations imitated unbundling occurring overseas at the time in which non-core businesses were disposed of as a means of generating better structure and deployment of capital to enhance shareholder value. Also, South African companies were attracted by the possibility of international listings, which had not been open to them before because of sanctions (Bhana, 2000).

With regard to Growthpoint, the divestment announcement stated that the rationale for the unbundling was as follows:

OK centre Ellisras is a share block company which lets the OK shopping centre located in Ellisras. The proceeds of the disposal will be utilized to reduce borrowings which were raised for the purpose of effecting the partial redemption of debentures, as set out in the circular to Growthpoint unit-holders dated 8 April 1997. (Growthpoint, 1997)

This announcement is consistent with the divestment strategy to reduce debt. Similarly, the statement by Standard Bank (Stanbic) indicated a continuation of a strategy to lower diversification:

The Stanbic unbundling is intended to achieve the following main objectives:

- To reduce the level of capital in Liberty Life to levels where returns on equity will be enhanced, while maintaining sufficient levels of capital for purposes of solvency and on-going business development.

- To continue the process of rationalizing the corporate structure of the Liberty Life group and by doing so, eliminating crossholdings and control structures.

- To further reduce the number of shareholder entry points into Stanbic and the Liberty Life group (The Stanbic-Liberty Life group). There are currently four companies, being Libsil, Liberty Life, Libhold and Stanbic within the Stanbic-Liberty Life group that are listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (The JSE).

- To unlock value for Libsil, Liberty Life and Libhold shareholders.

It is the view of the Boards of Directors of Libsil, Liberty Life and Libhold that shares of those companies have been trading on the JSE at discounts to their respective underlying values. Accordingly, the Stanbic unbundling is intended to assist in reducing that distortion and unlock value for shareholders. Shareholders should have benefit, after the implementation of the Stanbic unbundling, of greater investor flexibility with the ability to retain or dispose of their resultant Stanbic shares, in accordance with their investment policy or preferences. (Stanbic, 1999)

Both these statements for firm-divestment in Period 1 indicate divestment-involved business decisions consistent with decisions that increased value at other firms. For the subject firms, Figure 2a clearly shows that Growthpoint and Stanbic also experienced positive cumulative abnormal returns for 30 days following the announced divestments. While involving a limited sample, this provides tentative support for Proposition 1.

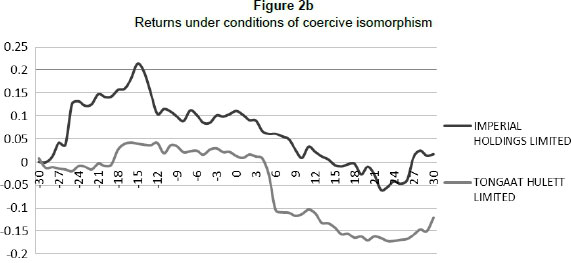

3.4.2 Period 2 (2003-2011)

Two companies, Tongaat Hulett and Imperial were selected for further analysis in Period 2, as they divested assets as a direct reaction to the BEE Act. The impact of BEE on firm-divestment is evidenced in the announcements made by these companies prior to unbundling. With regard to Tongaat Hulett, the divestment involved a 25 per cent BEE equity participation that received 99 per cent shareholder approval (Fin24, 2007). The corporate statement was as follows:

Further to the cautionary announcement dated 14 December 2006 regarding the proposed unbundling and listing on the JSE of Hulett Aluminium ("Hulamin") and the proposed Black Economic Empowerment transactions in respect of Tongaat-Hulett and Hulamin, shareholders of the company are advised that discussions are still in progress. Accordingly, shareholders of the Tongaat-Hulett Group are advised to continue exercising caution when dealing in the company's securities until a further announcement is made. (Tongaat Hulett Group, 2006; emphasis added)

With regard to Imperial, the cautionary announcement stated:

Diversified industrial group Imperial Holdings has concluded a Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) transaction in which it will sell a 7.25% stake in the company to Lereko Mobility in a deal worth R1.4bn. (Imperial Holdings Limited, 2007; emphasis added)

Both press releases indicate that conformance with the BEE Act represented a coercive influence behind each divestment. When separating the performance of firms that unbundled specifically due to BEE reasons, a decline in performance is indicated by Figure 2b. Both firms show a share price run-up prior to the divestment announcement that turned negative after the announcement. This provides tentative support for Proposition 2.

3.5 Supplemental analysis

We also compared the returns for selected firms (Standard Bank, Growthpoint, Imperial and Tongaat) for significant differences between the periods using Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests calculated for CARs for the 30-day period before the event and the 30-day period following the event. For Period 1 (1996-2002), the Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests revealed statistically significant increases in CARs for both Standard Bank and Growthpoint after divestment (z = -4.720, p < .001 and z = -4.762, p < 0.001, respectively) with large effect sizes (r = 0.612 and r = 0.618, respectively) in the first (early) period (1996-2002). The median CAR for Standard Bank increased from .078 before to .155 after the event. Similarly, the median CAR for Growthpoint increased from .024 before the event to .114 after the event. In Period 2 (2003-2011), the Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests showed significant decreases in CARs for both Imperial Holdings and Tongaat after their divestments (z = -4.782, p < .001 and -4.638, p < 0.001, respectively) with correspondingly large effect sizes (r = 0.62 and r = 0.60, respectively). The median CAR for Imperial Holdings decreased from .111 before the unbundling event to -.099 after the event. Also, Tongaat experienced a median fall from .021 before the BEE event, prompting unbundling to -.151 after the event. These results provide additional support for Propositions 1 and 2.

3.6 Discussion

Although efforts were made to procure reliable data on divestment activity by South African companies, the available observations and controls were not readily available to support large-sample statistical tests. However, an exploratory analysis of about 15 years of unbundling activity by South African firms was analysed for trends. As indicated earlier, this exploratory statistical analysis was supplemented with a mixed-methods approach that incorporated case study analyses.

The exploratory statistical analysis suggests that in Period 1 (1996-2002) when the democratic government was elected to power the general picture of gradual appreciation in ACARs (Average Cumulative Abnormal Returns) pre- and post-announcement of divestments following the lifting of apartheid restrictions supported a positive effect for mimetic isomorphism. While only the most tentative conclusions can be made regarding underlying causal factors at play, the supplementary case analysis of two companies also supports positive effects from corporate restructuring due to mimetic isomorphism. By and large, the transformation of South Africa from apartheid to a democratic government and the general removal of restrictions on corporate structure and corresponding mimetic effects of globalisation increased firm-value, or support Proposition 1

The Period 2 (2003-2011) exploratory statistical analysis examines the impact of BEE legislation or the coercive influence of divestment. The general trend of ACARs during this period is one of appreciation, although the causes of actual unbundling decisions by the firms concerned are largely undetermined. For example, other improvements, such as corporate governance (Abdo & Fisher, 2007) and continued mimetic forces, likely contributed to corporate restructuring. However, case analysis focusing on two companies that took direct action in response to the BEE Act provides a more definitive picture. The disclosures by the companies included in the case study support BEE as having a negative impact on firm-value. For both firms, negative CARs arose in the period after the decision to unbundle in order to accommodate the BEE Act. The additional analysis suggests that coercive intervention in corporate structures results in a loss of firm-value, or supports Proposition 2. Additional implications for research, policy and managers are discussed in the following subsections before identifying limitations as well as avenues for future research.

3.7 Research implications

While existing research has examined national institutions limiting organisational options (Dikova, Sahib & Witteloostuijin, 2010), we examine the impact of both the removal and imposition of restrictions on corporate restructuring. We find different aspects of a firm's institutional environment have divergent effects on corporate value. This goes beyond recent research that examines the institutional environment to determine whether it has moderating effects on diversification (Wan et al., 2011) and proceeds to consider whether the institutional environment may generate changes in corporate structure. The exploratory study findings indicate that isomorphism continues to apply in multinational settings and counters proposals that multinational firms decouple from institutional rules (Kostova, Roth & Dacin, 2008). We also establish that government influence as a factor behind corporate restructuring is an important consideration when research predominantly focuses on manager motivations (Martynova & Renneboog, 2008). Specifically, our research suggests that voluntary restructuring is likely to outperform involuntary restructuring. Further, our research suggests that factors provide impetus for political change and the institutional forces that affect firms or that firms are not immune to the effects of social movements. Specifically, the research suggests that emotions driving social movements may generate strategic change in corporations, and that this can help overcome legitimacy reinforcing the status quo (Johnson, Dowd & Ridgeway, 2006). This conclusion is consistent with research in South Africa demonstrating the changed expectations with regard to corporate governance changing the requirements for JSE-listed firms (Abdo & Fisher, 2007), and research by Bansal (2005) finding that institutional pressure increases sustainable development in firms with international experience.

3.8 Managerial implications

Our research reinforces the importance of management. With mimetic forces, managers are able to select the best options for divestment in order to improve performance, and, with government intervention, they can choose to divest portions of the firm that will have the least negative impact. However, the impact of a firm's institutional environment on its performance also suggests that managers need to consider strategies to influence their institutional environment (Hillman & Hitt, 1999; Weidenbaum, 1980). In China, foreign firms have confronted institutional uncertainty with relationship-building efforts with the government (Mondejar & Zhao, 2013), and this also appears to have occurred in South Africa. At a minimum, firms need to track potential impacts of government policy and then inform policymakers of potential implications (Weidenbaum, 1980). This suggests that managers may need to consider options for limiting government influence. Ironically, Beneish and colleagues (2008) suggest that diversification can protect firms from government regulation. While we observed increased divestment activity over time in South Africa resulting from the unbundling of conglomerates, it is possible other circumstances may drive increased diversification by firms.

3.9 Policy implications

Governments across the globe are experiencing change and are considering changes to economic policy. For example, the regulatory landscape continues to shift in Western countries following the 2008 debt crisis (Atkins, 2013), and, following the Arab Spring, Egypt and Tunisia are considering the integration of Islamic finance (Khalaf, 2013). Our exploratory findings lend tentative support to the position that government intervention through prescriptive legislation reduces firm-value, which thus supports the notion of increasing coercive isomorphism detrimentally influencing corporate structure and performance.

At the same time, the benefits obtained from coercive policies in South Africa were largely enjoyed by those with political connections, resulting in disillusionment with BEE - particularly among the poor (Amandla, 2012; Mondi, 2009). For example, African Rainbow Minerals obtained its first mine from AngloGold in a deal that largely benefited Patrice Motsepe, now the richest black South African, whose promises of building villages, schools and hospitals turned into broken dreams (Wild & Cohen, 2013). Additionally, judgments against political leaders' relatives who have achieved wealth remain unpaid, as the companies they ran went into bankruptcy. Consequently, over 700 workers who have two years of unpaid wages now live as beggars (Editor, 2012). The problems extend to alleged corruption. For example, new managers of Aurora Empowerment systems "vanished" with two months of wages (Sapa, 2010), and there have been instances of undue government influence in the awarding of contracts (Hofstatter & Afrika, 2013; Xulu & Marais, 2013).

These problems have triggered discontent with BEE policies and have brought about efforts to create more uniform policies in order to address economic inequality (Seekings & Nattrass, 2004). For example, unions have become more active, with 99 work stoppages in 2012, and with one labour leader highlighting the need to use increased political power to address economic disparities (Maylie, 2013). Implementing policy comes with costs and the benefits need to be commensurate with the price of implementation. An additional cost here is the need to consider policies to bail out struggling BEE companies (Mondi, 2009). For example, the Pamodzi Group that ran the previously mentioned mine subsequently went into liquidation (Sapa, 2012).

With this in mind, we do not make value judgements about the BEE Act and associated divestment, or about the benefits achieved. We also do not examine the impact of decreasing levels of government intervention, and there are reasons to suggest that uncertainty about policy could also have negative impacts. For example, corporate restructuring in South Africa may have been delayed until the BEE Act clarified the institutional environment (Wocke & Sing, 2013).

This suggests that mimetic forces for corporate restructuring were restrained by isomorphic uncertainty, leading to the conclusion that suboptimal government policy may be better than no government policy.

3.10 Limitations and future research

A primary limitation of our exploratory research is the small sample of observations available for our natural experiment with the changing institutional environment of South Africa. Examining institutional explanations for divestment was also hindered by divestitures lacking public-disclosure requirements (Brauer & Wiersman, 2012). The changes in South Africa were significant and research suggests that additional changes influenced the institutional environment (Mondi, 2009). For example, in parallel with the implementation of BEE, improvements in corporate governance were made with JSE-listed firms being required to comply with the 2002 King Committee Report's seven components of good corporate governance (Abdo & Fisher, 2007). This suggests another limitation, in that we only examined a single nation, when understanding the business-government relationship requires an understanding of institutional environments that vary by nation (Hillman & Keim, 1995). For example, high (US) or low (China) institutional development drives differences in M&A activity (Lin et al., 2009). Another limitation is that we do not examine differences in the quality of management, although we conclude that management makes a difference. In closing, our research reinforces the need to examine the impact of a firm's institutional environment and the consideration that different forces will have dissimilar impacts on firm-value. Future research might also use a mixed-methods approach where numerical data is scarce in order to combine statistical analyses with "ideal-type" case studies.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the editor, Professor Leon Oerlemans, for his expert suggestions in improving the paper.

References

ABDO, A. & FISHER, G. 2007. The impact of reported corporate governance disclosure on the financial performance of companies listed on the JSE. Investment Analysts Journal, 66:43-56. [ Links ]

AFSHAR, K.A., TAFFLER, R.J. & SUDARSANAM, P.S. 1991. The effect of corporate divestments on shareholder wealth: The UK experience. Journal of Banking and Finance, 16:115-135. [ Links ]

AMANDLA. 2012. Our wealth, our poison. Available at: http://www.amandla.org.za/amandla-magazine/124-amandla-issue-2627/1592-our-wealth-our-poison--by-amandla-correspondents [accessed 201402-18]. [ Links ]

ANGLOGOLD. 2007. Bobby Godsell retires as CEO at AngloGold Ashanti. Press Release: 31 July. Available at: http://www.anglogold.com/Additional/Press/2007/Bobby+Godsell+Retires+as+CEO+at+AngloGold+Ashanti.htm [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

ATKINS, R. 2013. With the volume down. Financial Times, 12 February:7. [ Links ]

BANSAL, P. 2005. Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic Management Journal, 26:197-218. [ Links ]

BENEISH, M., JANSEN, I., LEWIS, M., & STUART, N. 2008. Diversification to mitigate expropriation in the tobacco industry. Journal of Financial Economics, 89:136-157. [ Links ]

BERGER, P. & OFEK, E. 1995. Diversification's effect on firm value. Journal of Financial Economics, 37:39-65. [ Links ]

BHANA, N. 2000. Overseas listing by companies listed on the Johannesburg Securities Exchange and its impact on shareholder wealth. Investment Analyst Journal, 51:37-47. [ Links ]

BHANA, N. 2004. Performance of corporate restructuring through spin-offs: Evidence from JSE-listed corporations. Investment Analysts Journal, 60:5-5. [ Links ]

BHANA, N. 2006. The effect of corporate divestments on shareholder wealth: The South African experience. Investment Analysts Journal, 63:19-30. [ Links ]

BRAUER, M. 2006. What have we acquired and what should we acquire in divestiture research? A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 32:751-785. [ Links ]

BRAUER, M. & WIERSMAN, M. 2012. Industry divestiture waves: How a firm's position influences investor returns. Academy of Management Journal, 55:1472-1492. [ Links ]

CAPRON, L. & GUILLEN, M. 2009. National corporate governance institutions and post-acquisition target reorganization. Strategic Management Journal, 30:803-833. [ Links ]

CAPRON, L., MITCHELL, W. & SWAMINATHAN, A. 2001. Asset divestiture following horizontal acquisitions: A dynamic view. Strategic Management Journal, 22:817-844. [ Links ]

CARNEY, M., GEDAJLOVIC, E., HEUGENS, P. & VAN OOSTERHOUT, J. 2011. Business group affiliation, performance, context, and strategy: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 54: 437-460. [ Links ]

CASTLE, J. & KANTOR, B. 2000. Tracking stocks - an alternative to unbundling for the South Africa group. Investment Analysts Journal, 51:49-56. [ Links ]

CORREIA, C., FLYNN, D., ULIANA, E. & WORMALD, M. 2011. Financial Management. (7th ed.) Johannesburg: Juta. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J. 2003. Mixed methods procedures. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA:Sage:208-227. [ Links ]

DAVIS, G. & THOMPSON, T. 1994. A social movement perspective on corporate control. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39:141-173. [ Links ]

DE JONG, A., ROSENTHAL, L. & VAN DIJK, M.A. 2009. The risk and return of arbitrage in dual-listed companies. Review of Finance, 13(3):495-520. [ Links ]

DE SOTO, H. 2013. The economic roots of the Arab Spring. McKinsey & Company. Available at: http://voices.mckinseyonsociety.com/economic-roots-of-the-arab-spring/ [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

DIKOVA, D., SAHIB, P. & WITTELOOSTUIJIN, A. 2010. Cross-border acquisition abandonment and completion: The effect of institutional differences and organizational learning in the international business service industry. Journal of International Business Studies, 41:223-245. [ Links ]

DIMAGGIO, P. & POWELL, W. 1983. The Iron Cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48:147-160. [ Links ]

EDITOR. 2012. Aurora's Zuma must be held to account for mine debacle. Times Live. Available at: http://www.timeslive.co.za/opinion/editorials/2012/01/13/aurora-s-zuma-must-be-held-to-account-for-mine-debacle [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

FIN24. 2007. Tongaat Hulett posts R155m loss. Available at: http://www.fin24.com/Companies/Tongaat-Hulett-posts-R155m-loss-20070730 [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

FIRTH, M., GONG, S. & SHAN, L. 2013. Cost of government and firm value. Journal of Corporate Finance, 21:136-152. [ Links ]

FITZPATRICK, D. & LUBLIN, J. 2009. Bank of America chief resigns under pressure. Wall Street Journal. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB125434715693053835.html [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

GELETKANYCZ, M. & HAMBRICK, D. 1997. External ties of top executives: Implications for strategic choice and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42:654-681. [ Links ]

GROWTHPOINT. 1997. Cautionary announcement. Available at: http://whoswho.co.za/companyarticles/GRT?page=18&destination=company%252FGRT%252Fuser%252Fpress office [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

GOSTNER, K. 2002. An assessment of the economic impact of the primary listings by South African companies on the London Stock Exchange, 1997-2001. Business Map Foundation. Available at: http://www.fdi.net/documents/WorldBank/databases/busmap/sacompaniesonlse.htm [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

HAGEL III, J. & SINGER, M. 2000. Unbundling the corporation. Available at: http://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/Unbundlingthecorporation1069 [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

HAGERTY, J. & CHON, G. 2011. ITT plans breakup as bigness loses favor. Wall Street Journal 13 January. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704803604576077501374387900.html [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

HATTINGH, S. 2007. BHP Billiton and SAB: Outward capital movement and the international expansion of South African corporate giants. Available at: http://www.taxjustice.net/cms/upload/pdf/Ilrig0809South African giants.pdf [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

HALEBLIAN, J., DEVERS, C., McNAMARA, G., CARPENTER, M. & DAVISON, R. 2009. Taking stock of what we know about mergers and acquisitions: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 35:469-502. [ Links ]

HEELEY, M., KING D. & COVIN, J. 2006. R&D investment level and environment as predictors of firm acquisition. Journal of Management Studies, 43:1513-1536. [ Links ]

HERSZENHORN, D. 2014. Ukraine parliament moves swiftly to dismantle president's government. New York Times, 23 February. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/24/world/europe/ukraine.html?r=0 [accessed 2014-02-23]. [ Links ]

HILLMAN, A. & HITT, M. 1999. Corporate political strategy formulation: A model of approach, participation, and strategy decisions. Academy of Management Review, 24:825-842. [ Links ]

HILLMAN, A. & KEIM, G. 1995. International variation in the business-government interface: Institutional and organizational considerations. Academy of Management Review, 20:193-214. [ Links ]

HILLMAN, A., ZARDKOOHI, A. & BIERMAN, L. 1999. Corporate political strategies and firm performance: Indications of firm-specific benefits from personal service in the U.S. government. Strategic Management Journal, 20:67-81. [ Links ]

HITE, G. & OWERS, J. 1983. Security price reactions around corporate spin-off announcements. Journal of Financial Economics, 12:409-435. [ Links ]

HOFSTATTER, S. & AFRIKA, M. 2013. Embarrassed Sasol axes shady BEE partner. Times Live. Available at: http://www.timeslive.co.za/local/2013/08/04/embarrassed-sasol-axes-shady-bee-partner [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

HUY, Q. 2013. Emotions in strategic organization: Opportunities for impactful research. Strategic Organization, 10:240-247. [ Links ]

IMPERIAL HOLDINGS LIMITED. 2008. Available at: http://www.imperial.co.za/CMSFiles/File/Documents/Cautionary%20250208%20UPDATE%20v2.pdf [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

JOHNSON, C., DOWD, T. & RIDGEWAY, C. 2006. Legitimacy as a social process. Annual Review of Sociology, 32:53-78. [ Links ]

JORY, S. & MADURA, J. 2009. Acquisitions of bankrupt assets. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 49:748-759. [ Links ]

KANTOR, B. 2001. Adding value for shareholders in South Africa: An analysis of the Rembrandt restructuring. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 14:49-57. [ Links ]

KEIL, T., LAAMANEN, T. & McGRATH, R.G. 2013. Is a counterattack the best defense? Competitive dynamics through acquisitions. Long Range Planning, 46(3): 195-215. [ Links ]

KHALAF, R. 2013. Underfunded renaissance. Financial Times, 11 February:7. [ Links ]

KHANNA, T. & PALEPU, K. 2000. Is group affiliation profitable in emerging markets? An analysis of diversified Indian business groups. Journal of Finance, 55:867-891. [ Links ]

KIERNAN, P. 2013. Mining to politicians: Loosen grip. Wall Street Journal, 23 October:B8. [ Links ]

KING, D., DALTON, D., DAILY, C., & COVIN, J. 2004. Meta-analyses of post-acquisition performance: Indications of unidentified moderators. Strategic Management Journal, 25:187-200. [ Links ]

KOSTOVA, T., ROTH, K. & DACIN, M. 2008. Institutional theory in the study of multinational corporations: A critique and new directions. Academy of Management Review, 33:494-1006. [ Links ]

KUSSTATSCHER, V. & COOPER, C. 2005. Managing emotions in mergers and acquisitions. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

LEE, D. & MADHAVAN, R. 2010. Divestiture and firm performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 36:1345-1371. [ Links ]

LIN, Z., PENG, M., YANG, H. & SUN, S. 2009. How do networks and learning drive M&As? An institutional comparison between China and the United States. Strategic Management Journal, 30:113-1132. [ Links ]

LOCKETT, A. & WILD, A. 2013. A Penrosean theory of acquisitive growth. Business History, 55:790-817. [ Links ]

MARTYNOVA, M. & RENNEBOOG, L. 2008. A century of corporate takeovers: What have we learned and where do we stand. Journal of Banking and Finance, 32:2148-2177. [ Links ]

MATHEWS, C. & MAQUTU, A. 2013. Eking out a living. Financial Mail, 7 May. Available at: http://www.financialmail.co.za/fm/CoverStory/2013/05/02/eking-out-a-living [accessed 2014-02-18 2014. [ Links ]

MAYLIE, D. 2013. South Africa unionist sparks alarm. Wall Street Journal, 28 October:A9. [ Links ]

McADAM, D. 1982. Political process and the development of black insurgency 1930-1970. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

McGROARTY, P. & MAYLIE, D. 2012. South Africa falters as unrest spreads. Wall Street Journal, 11 October. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10000872396390444433504577649590455024910 [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

MEREDITH, J. 1998. Building operations management theory through case and field research. Journal of Operations Management, 16:441-454. [ Links ]

MIZRUCHI, M. & FEIN, L. 1999. The social construction of organization knowledge: A study of the uses of coercive, mimetic, and normative isomorphism. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44:653-683. [ Links ]

MOLLER, V. 1998. Quality of life in South Africa: Post-apartheid trends. Social Indicators Research, 43: 27-68. [ Links ]

MONDEJAR, R. & ZHAO, H. 2013. Antecedents to government relationship building and the institutional contingencies in a transition economy. Management International Review, 53:579-605. [ Links ]

MONDI, L. 2009. BEE is dead! Long live BEE. Transformation Audit:14-20. [ Links ]

MORRISON, K.L. 2006. Marx, Durkheim and Weber: Formations of modern social thought. (2nd ed.) London: Sage. [ Links ]

MOSCHIERI, C. 2011. The implementation and structuring of divestitures: The unit's perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 32:368-401. [ Links ]

MOSCHIERI, C. & MAIR, J. 2008. Research on corporate divestitures: A synthesis. Journal of Management and Organization, 14:399-422. [ Links ]

NYSE. 2013. Company profile. Available at: http://www.nyse.com/about/listed/au.html [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

O'NEILL, H.M., POUDER, R.W. & BUCHHOLTZ, A.K. 1998. Patterns in the diffusion of strategies across organizations: Insights from the innovation diffusion literature. Academy of Management Review, 23(1): 98-114. [ Links ]

PORTER, M. 1980. Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

PORTER, M. & VAN DER LINDE, C. 1995. Green and competitive. Harvard Business Review, Sept- Oct:120-134. [ Links ]

RADEBE, J. 1998. Public address, 13 November. Available at: http://www.info.gov.za/speeches/1998/98c235749811433.htm [accessed 2013-10-24]. [ Links ]

ROSSOUW, G. 1997. Unbundling the moral dispute about unbundling in South Africa. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(10):1019-1028. [ Links ]

SANDERS, W. 2001. Behavioral responses of CEOs to stock ownership and stock option pay. Academy of Management Journal, 44:477-492. [ Links ]

SAPA. 2000. German business confidence in SA doubles. News 24 archives, 17 August. Available at: http://www.news24.com/xArchive/Archive/German-business-confidence-in-SA-doubles-20000817 [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

SAPA. 2010. Aurora bosses disappear with worker wages. MoneyWeb, 6 April. Available at: http://www.moneyweb.co.za/moneyweb-mining/aurora-bosses-disappear-with-workers-wages [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

SAPA. 2012. Pamodzi: End in sight. Fin24. Available at: http://www.fin24.com/Companies/Mining/Pamodzi-End-in-sight-20120315 [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

SCHNEIBERG, M. & LOUNSBURY, M. 2008. Social movements and institutional analysis. In M. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin & R. Suddaby (eds), Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism. Los Angeles: Sage:650-672. [ Links ]

SCOTT, W. 1995. Institutions and organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

SEEKINGS, J. & NATTRASS, N. 2004. The post-apartheid distributional regime. CSSR Working Paper no. 76. [ Links ]

SHIMIZU, K. 2007. Prospect theory, behavioral theory, and the threat-rigidity thesis: Combinative effects on organizational decisions to divest formerly acquired units. Academy of Management Journal, 50:1495-1514. [ Links ]

SOULE, S., SWAMINATHAN, A. & TIHANYI, L. 2014. The diffusion of foreign divestment from Burma. Strategic Management Journal, 35:1032-1052. [ Links ]

SOUTHAFRICA.INFO. 2013. 72 days that shaped South Africa. Available at: http://www.southafrica.info/about/history/72days2.htm [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

STANBIC. 1999. Cautionary announcement. Available at: https://trade.imara.co/free/sens/dispnews.phtml?tdate=19990819075034&seq=1410&scheme=imaraco [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

TONGAAT HULETT GROUP. 2006. Media release. Available at: http://www.tongaat.com/downloads/THG4Press131206.pdf [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

VILLALONGA, B. & MCGAHAN, A. 2005. The choice among acquisitions, alliances, and divestitures. Strategic Management Journal, 26:1183-1208. [ Links ]

VOSS, C.A., TSIKRIKTSIS, N. & FROHLICH, M. 2002. Case study research in operations management. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 22(2):195-219. [ Links ]

WALTERS, S. & PRINSLOO, J. 2002. The impact of offshore listings on the South African economy. SA Reserve Bank Quarterly Bulletin, 3:60-71. [ Links ]

WAN, W., HOSKISSON, R., SHORT, J. & YIU, D. 2011. Resource based theory and corporate diversification: Accomplishments and opportunities. Journal of Management, 37:1335-1368. [ Links ]

WEIDENBAUM, M. 1980. Public policy: No longer a spectator sport for business. Journal of Business Strategy, 1:46-53. [ Links ]

WILD, F. & COHEN, M. 2013. Mandela's wealth-sharing dream fades in South Africa. Bloomberg. Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-07-22/mandela-s-wealth-sharing-dream-fades-in-south-africa.html [accessed 2013-10-24]. [ Links ]

WOCKE, A. & SING, L. 2013. Inward FDI in South Africa and its policy context. Available at: http://www.vcc.columbia.edu/files/vale/documents/SouthAfricaIFDI-May82013-FINAL.pdf [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

WORLD BANK. 2013. South Africa. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/country/south-africa [accessed 2014-02-18]. [ Links ]

XIA., J. & LI, S. 2013. The divestiture of acquired subunits: A resource dependence approach. Strategic Management Journal, 34:131-148. [ Links ]

XULU, L. & MARAIS, J. 2013. BEE deal "not forced" on Gold Fields. Business Times, 22 September:1. [ Links ]

YIN, R.K. 1994. Case study research (2nd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [ Links ]

Accepted: February 2015

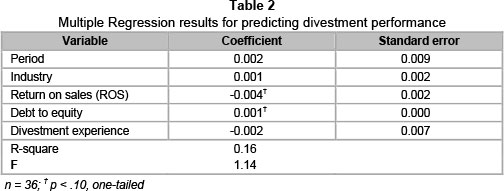

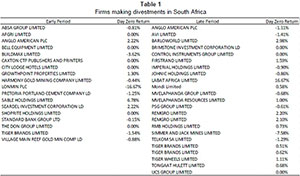

Appendix

As part of a preliminary analysis, we used the Day Zero Return as the dependent variable in a regression model. Our intent was to see whether available information could explain performance differences. We divided the sample into different periods using a dummy variable, with 0 signifying divestments in the early period and 1 signifying divestments in the later period. We also controlled for industry using manufacturing as the reference category (0), and separately identifying mining (1), financial (2), telecommunications (3), consumer products (4), hotels (5), and technology (6). We also controlled for a divesting firm's prior performance using return on sales (ROS) and debt capacity (debt-to-equity), and prior divestment experience using a count variable. These factors are considered relevant, as research suggests that firms divest to alleviate financial constraints and that prior divestment makes future divestment a more viable strategy (Shimizu, 2007; Soule, Swaminathan & Tihanyi, 2014) as a result of higher debt levels contributing to divestment activity (Lockett & Wild, 2013). In a regression analysis (see Table 2), lower firm-performance and higher firm-debt predicted divestment (p < .10; one-tailed tests). Other factors, including differences in time period, were not significant. We concluded that the insignificant results could be attributed to the small sample size and to time differences serving as a poor differentiator for the reason for divestment. For example, mimetic isomorphic forces did not diminish when coercive isomorphic forces resulting from BEE legislation appeared. As a result, we focused on case analysis where divestment fitted ideal types.