Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

On-line version ISSN 2222-3436

Print version ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.18 n.2 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2222-3436/2015/v18n2a1

ARTICLES

Effects of intellectual capital on qualitative and quantitative performance: Evidence from Turkey

Gökhan ÖzerI; Ercan ErgunI; Osman YilmazII

IGebze Institute of Technology, Turkey

IIMersin Metropolitan Municipality, Turkey

ABSTRACT

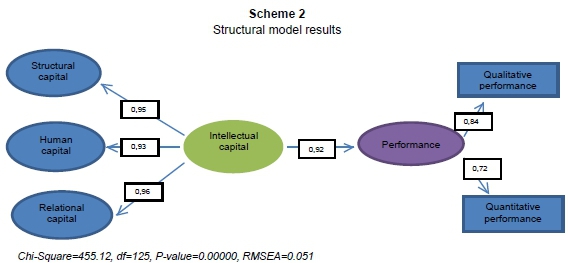

Intellectual capital is among the new, advanced management notions developed to overcome the inadequacy of previous administrations, to adapt to new situations and forge ahead of the competition. Intellectual capital means the information, experience and skills that offer advantage in competition and reveal the values existing within the structure of an enterprise. These values also exist in the relationship between the enterprise and the environment and with the employees. Although some research studies on intellectual capital (IC) have been conducted, to date no research has been carried out on the effects of IC on qualitative and quantitative organizational performance. For this reason, IC and its effects on firm performance (both qualitative and quantitative) were evaluated in this study. Following the evaluation of the intellectual capital and its sub-elements, the differentiation of the sub-elements is made. Then the reliability and validity of these sub-factors are calculated. The intellectual capital model has been tested by the structural equality model (SEM). According to research results, IC explains 92 per cent of a firm's performance. The effect of IC on qualitative performance is 0,84, while on quantitative performance it is 0,72. RC impresses qualitative performance with coefficient 0,94, quantitative performance with coefficient 0,60; HC impresses qualitative performance with coefficient 0,92, quantitative performance with coefficient 0,54 less; SC impresses qualitative performance with coefficient 0,90, quantitative performance with coefficient 0,53. According to the results of the research, IC affects both the qualitative and the quantitative performance of firms by supplying extensive knowledge to the managers.

Key words: intellectual capital (IC), relational capital (RC), structural capital (SC), human capital (HC), quantitative performance, qualitative performance

1 Introduction

As a result of changes in the transition to an information society, as well as changes in management, customers, competition, market structures and organizational sense, the classic paradigms of the concept of governance have changed, and IC has become a highly valued aspect of business (Edvinsson, 2002). Even though the importance of IC has been identified, there is no unified discourse on the issue in the literature.

Opinions on the definition of IC vary. Data is not available in sufficient detail on the elements and measurement of IC studies that demonstrate the effects of the mutual interaction of the elements of capital on an entity's performance. In the model presented by Bontis et al., it is recommended that the main dimensions of the sub-dimensions for each of the classifications, with indicators for each sub-dimension, should be developed (Bontis, Keow, Chua & Stanley, 2000).

In this study, we define, within the framework of the literature review, three main dimensions of intellectual capital: human capital (HC), structural capital (SC) and relational capital (RC). After a discussion of each component of IC as a whole, we present the individual sub-factors. We then calculate the reliability and validity of these sub-factors. We also test the effects of the IC model, as well as the effects of sub-factors on quantitative and qualitative performance by analyzing the structural equation model (SEM) and the structure of intellectual capital.

For this purpose, the sub-factors of intellectual capital and its elements, and the sub-factors of the scale of performance were identified by means of a study questionnaire conducted for business owners and managers in Turkey. In the context of structural capital, organizational culture, corporate image and brand, information technology, R&D and innovation, intellectual property, management philosophy and process factors were evaluated. In terms of human capital, technical knowledge and skills, the motivation of employees working in an innovative atmosphere and social capital factors were evaluated. In the context of relational capital, customer relationships, supplier relationships, network partners, relations, investor/public relations and public affairs were evaluated.

The impact on the overall performance was measured by evaluating the effects of intellectual capital on performance (Akpinar, 2003). When measuring the performance by enterprises, qualitative and quantitative performance decompositions and relevant studies are recommended (Ergün, 2003).

In this study, IC reviews were conducted via SC, RC and HC. Their effects on quantitative and qualitative performance were investigated both separately and together.

Studies on the effect of sub-components and the interaction of these components and on quantitative and qualitative performance will contribute to the literature and will be a source for future studies.

Finally, the effects of the IC components and sub-factors on the quantitative and qualitative performance of enterprises were examined, and recommendations were made to researchers and practitioners in line with the results presented.

2 Literature review

The first definition of IC as it relates to these assets was offered by Thomas A. Stewart in a 1991 Fortune article entitled 'Brainpower'. According to this definition, IC constitutes all of the data or information which provides a competitive advantage for a firm (Stewart, 1991).

Leif Edvinsson, known as the first professional intellectual capital manager and another pioneer on the subject, defines IC as knowledge that can be turned into an asset (Edvinsson, 1997).

In drawing attention to the dynamics of the concept of intellectual capital, Nick Bontis also stated that "rather than being a static entity, IC is a concept creating added value in economic and social aspects when it is applied to a firm's necessaries" (Bontis, 1998). In this context, it can be emphasized that a company's intangible and invisible assets can created a very significant difference to the organizational functioning and results, equal to those of tangible assets, and sometimes even more (Bontis, 1999).

As a result of these studies, different models and concepts related to IC have emerged. Consensus was reached on the components of IC, which, although intangible, deliver positive financial results related to the human input (Bontis, 2001).

In order to assess IC in the strictest sense, knowing the components comprising IC helps in understanding its nature (Huang, Luther & Tayles, 2007). Researchers have studied these definitions and classifications at length (Brooking, 1996; Edvinsson, 1997; Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Sveiby, 1998). Further, in order to better identify and analyze IC, researchers have developed several IC models (Bontis et al., 2000).

IC is regarded as one of the most important knowledge-based strategic assets for firms (Rehman, Rehman & Zagid, 2011). In this study, within the framework of the literature review, we define three basic dimensions of the components of IC as HC, SC and RC, according to consensus.

2.1 Structural capital

Structure is a ompany's skeleton, a concept that was created to enable firms to conduct business more effectively and more successfully (Nordstrom & Ridderstrále, 2000). IC was established and developed according to the concept of SC. If the content is weak, it is unable to provide comparative advantage for the company (Bontis, 1998).

SC includes mechanisms and structures inside the organisation. Some researchers have defined SC as every component of the organisation which supports workers' working hours and is left in the workplace after work (Edvinsson & Malone, 1997). The presence of SC is in question in cases where the business structure provides comparative advantages to the company (Kursunmaden, 2007).

The other elements of IC can be utilised via SC. Even in cases when HC and RC are high, if the structural condition is unstisfactory, it will be impossible to deliver the necessary sustainable performance. IC cannot be evaluated on these components alone. SC transforms employees' knowledge and that in relations into explicit knowledge for the company and provides permanence to the firm (Akpinar, 2003; García-Álvarez, Mariz-Pérez & Álvarez, 2011; Seetharaman, Low & Saravanan, 2004).

SC is the encoded and institutionalised form of organisational culture, organisational philosophy, business processes, intellectual properties, R&D and the innovativeness of organisational information and ability (Maditinos, Chatzoudes, Tsairidis & Theriou, 2011). Bontis et al. (2000) maintain that SC includes systems, procedures, databases, copyrights, patents, structural mechanisms, rules, policies and other important issues necessary for managers to make important decisions.

2.2 Human capital

Human capital was ignored after the industrial revolution, as productivity was the only important organisational goal. This approach was first suggested by Taylor, after whom it is named. After the unionisation of workers, it was abandoned in favor of the human relations approach. The rise of this argument was owing to the fact that productivity has meaning as long as there are consumers. However, the approach did not give due value to HC (Mehralian, Rajabzadeh, Sadeh & Rasekh, 2012; Bruggen, Vergauwen & Dao, 2009; Selemi, Ashour & Bontis, 2007).

Following the development of communication technologies and social networks, as well as changes in the market-place, HC was recognised as more important than the other capital components of organisations. This revolution in the understanding of HC resulted in a great deal of research, much of which concluded that HC directly affects firm performance. HC is the ability to derive the best results from company employees, with their knowledge, skills, and experience (Bontis, 1998). HC is the source, store and limiting factor of information, and the source of creativity. New products can be developed only through HC (Moon & Kym, 2006; Muzaffar, 2011; OECD, 2007; Sveiby, 2001). HC is an element which depends on employee skills like technical knowledge and skill, motivation, innovativeness, adaptation and social capital (Chen, Cheng & Hwang, 2005).

2.3 Relational capital

Embedded knowledge and value in a company's relations and the development of the company's relations within its environment constitute its RC. This knowledge and value, as an element of IC, consists of mutual attachment and satisfaction in the relations resulting from long-term connections (Saint-Onge, 1998; Bontis, 1999; Bontis et al., 2000; Yang, Wang, Wong & Lai, 2008). The relations that encompass RC are: market, customers, suppliers, trade associations, community, partnerships and competitors (Bontis et al., 2000).

Although RC is the most distinct features of intellectual capital, it is generally one of the most poorly managed of intellectual assets (Stewart, 1991). It includes all the relation-ships with external stakeholders and organisations. These relationships are: market, customers, suppliers, trade associations, com-munity, partnerships and competitors (Bontis et al., 2000; Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005; Liao, Huang & Hsu, 2010; Kim & Kumar, 2009).

3 Research methodology

Intellectual capital, by its very nature, is difficult to measure and record (Marr, 2004). IC is measured in two ways: management and components (Luthy, 1998). To measure on the basis of elements requires, respectively: a) determining the true scope of the sub-dimensions of intellectual capital; and b) improving the categorisation of the sub-dimensions of intellectual capital, HC, SC and RC, and the sub-dimensions for each.

The balanced use of both quantitative and qualitative performance measures has become a necessity for enterprises, and it will be helpful for organisations in transmitting information to stakeholders (Bilgen, 2001). Using these two approaches, data can be obtained pertaining to IC performance and its sub-factors to identify strengths and weaknesses. The quantitative and qualitative performance of IC can be compared with that of similar firms (Moon & Kym, 2006).

It is advisable to use a Likert-type scale to measure IC (Bontis, 1998). In this case, a Quintet Likert scale was used to measure the questions. A comprehensive survey, including a knowledge form, IC components (structural capital, human capital and relational capital), qualitative performance and quantitative performance inventories, has been developed in a study based on the literature review (Bontis, 1998; Bontis, 2001; Brooking, 1996; Dzinkowski, 2000; Edvinsson, 1997; Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Marr, 2004; Marr, 2005; Moon & Kym, 2006; Petty & Guthrie, 2000; Roos & Roos, 1997; Sullivan, 2000; Sveiby, 1998; Wang & Chang, 2005) and in accordance with Turkish firms.

Regarding IC and its sub-factors, even under similar circumstances, the entity has shown better performance characteristics. A performance evaluation for both a quantitative and a qualitative evaluation is needed. In our study, we examined the individual and overall effects of SC, RC and HC, which are the sub-dimensions of IC, on qualitative and quantitative performance.

To be able to carry out a performance evaluation, both quantitative and qualitative evaluations are needed. The performance scale has been adopted from Yilmaz, Alpkan & Ergun (2005).

In the analysis section of this study, a structural equation modeling analysis was conducted as follows: a) A structural model of the relationships between variables, which determined the theoretical basis for establishment of the model; b) A path diagram of relationship arm coefficients was determined; c) Harmonisation of statistics on the goodness of the model were examined; d) The structural model results were interpreted. Prior to this analysis, factor analysis and factor analysis with implicit structures also have to be controlled (Mulaik & Millsap, 2000).

In our study, by adhering to this process, after evaluating IC and its sub-factors, a separation of the sub-factors was specifically carried out. After this, the IC model and structural equation model (SEM) were tested by calculating the reliability and validity of these sub-factors. The 8:51 LISREL package program was used during the analysis. With the idea that all the companies in Turkey were included in the sample, a simple random sampling method was adopted.

According to this method, each element has the same probability of being included in the sample (Arikan, 2004). The weight of each element is therefore the same as all the others.

A survey method was chosen as a method of data collection on the Internet, and a Google docs survey was augmented by the application of this subject.

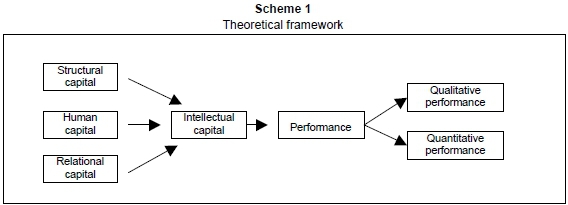

A total of 1,050 firms in different sectors were covered in the study. The theoretical framework of the research is outlined in Scheme 1.

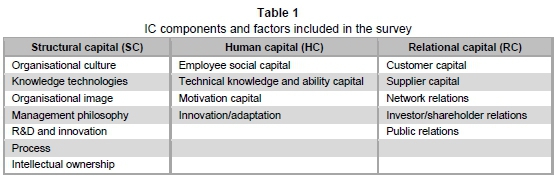

As shown in the scheme, it was assumed that SC, HC and RC constitute IC, and IC has effects on both the qualitative and quantitative performance of the firms. Inventories included in the survey and their relevance to components of IC are provided in Table 1.

4 Limitations and assumptions

This research is included in studies of the components of IC (relational capital, structural capital and human capital).

Research: Because of time restrictions, economic constraints and research limitations, this research was conducted under the following conditions:

Constraints in terms of subject: There are numerous ways of measuring and reporting on intellectual capital. In this study, we used the survey method, which reports on the "basis of the components of intellectual capital".

Constraints in terms of time: This study was conducted from 2009 to 2012, with the survey measuring perceptions of the data during this period.

Constraints in application: Since the questionnaires for this study were dealt with on the Internet, they could be applicable only to chambers of industry and commerce and the managers of member firms who have e-mail addresses. As set out in the Methodology section, our study contains some limitations, and the results should be evaluated in this context. Although the research was made with all the scales and in all the Turkish sectors, no further analysis was carried out in this study. For this reason, the results should be considered general, not industrial.

At the sectoral level, analysis of the effects of IC and its sub-elements on quantitative and qualitative performance and the effects of IC sectoral variations can be demonstrated. The differences in sectoral emphasis on the elements of IC can be seen. In an analysis categorising according to the business scale, emphasis analysis can be carried out determining whether or not the effects of IC and its sub-elements on the qualitative and quantitative performance show changes, and determine whether there is any variation.

This research involved business managers and enterprise owners. As IC is associated with all internal and external elements of the company, the study can be expanded by applying it to all internal and external stakeholders of enterprises.

This was implemented in various Turkish sectors using different scales. In this respect, the study presents the overall level of intellectual capital. Considering that information can be collected anywhere in the information society and knowledge management culture, the collected data is assumed to be in compliance with regulation.

5 Findings and results

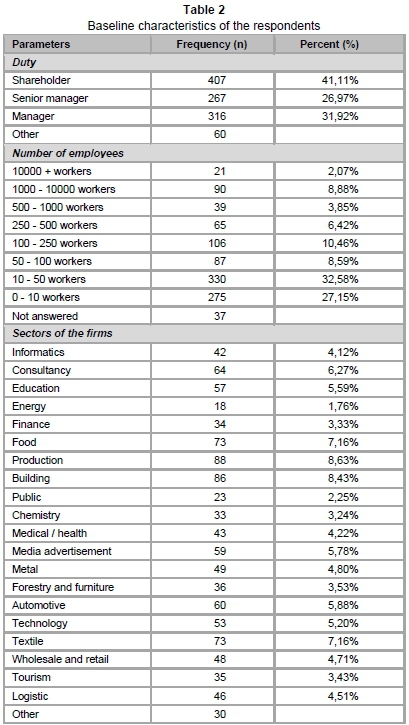

Structural equation modeling was used to examine data gathered as part of the research. The baseline characteristics of the respondents were examined by Frequency Analysis. The participants' duty, the number of employers and firm sectors covered in the survey are provided in Table 2.

According to the table, it can be argued that a sample of the research is sufficient to demonstrate the current economic state of Turkey. Rates of firm sectors and firm size (based on number of employees according to enterprise surveys) were in accordance with the Turkish macro-economic structure.

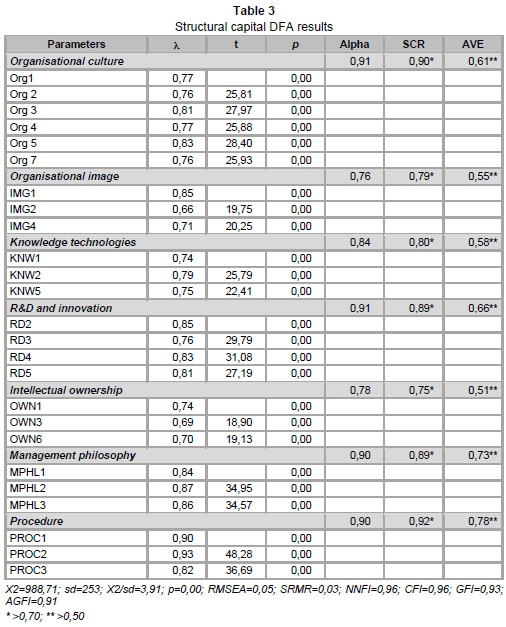

DFA analysis results of the data for SC are provided in Table 3.

Table 3 shows that SC accordance with the model is significant, and other indices (RMSEA=0,05; SRMR=0,03; NNFI=0,96; CFI=0,96; GFI=0,93; AGFI=0,91) support the model.

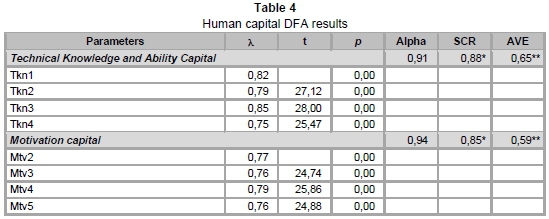

Human capital DFA results are provided in Table 4.

Similar to SCM, the human capital model (HCM) is also suitable, and other indices (RMSEA=0,07; SRMR=0,05; NNFI=0,95; CFI=0,97; GFI=0,96; AGFI=0,93) support the current model. There are four factors and 12 observed parameters for the given factors.

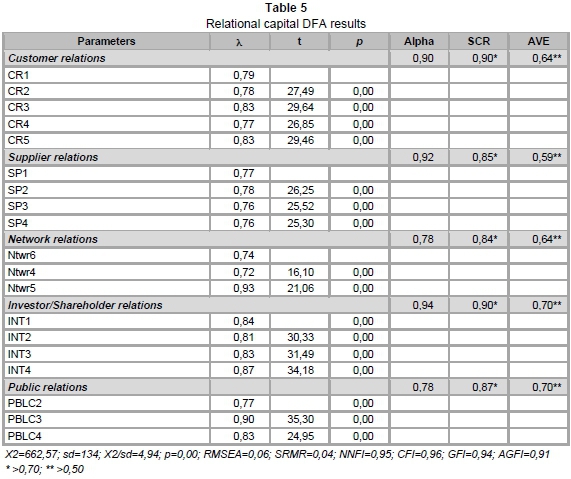

Relational capital DFA results are provided in Table 5.

The relational capital model (RCM) is also suitable, and other indices (RMSEA=0,06; SRMR=0,04; NNFI=0,95; CFI=0,96; GFI=0,94; AGFI=0,91) support it. There are five factors and 19 observed parameters for the given factors.

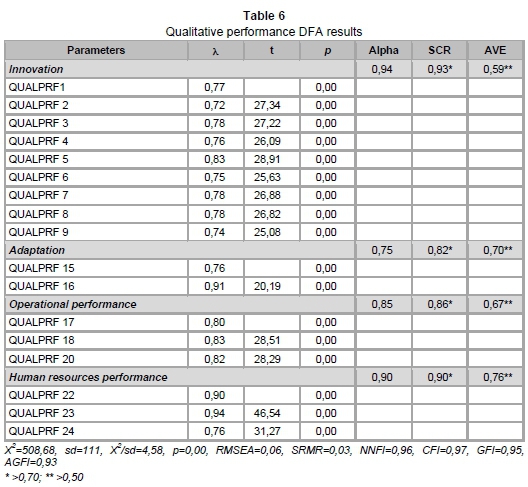

Qualitative performance DFA results are provided in Table 6.

The qualitative performance model (QLPM) is suitable, and other indices (RMSEA=0,06,SRMR=0,03, NNFI=0,96, CFI=0,97, GFI=0,95, AGFI=0,93) support it. There are four factors and17 observed parameters for the given factors.

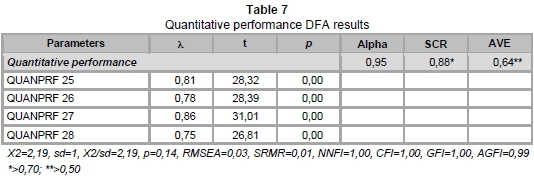

Quantitative performance DFA results are provided in Table 7.

The quantitative performance model (QNPM) is suitable, and other indices (RMSEA=0,03, SRMR=0,01, NNFI=1,00, CFI=1,00, GFI=1,00, AGFI=0,99) support the current version. There is one factor and four observed parameters for the given factor. Structural model results of the research are provided in the Scheme below.

Results show that the correlation effects of components of the IC with itself are RC (r=0,96), SC (r=0,95) and HC (r=0,93), respectively. The correlation effect of IC with qualitative performance (r=0,84) is higher than with quantitative performance (0,72).

6 Conclusion

With the information and explanatory text presented above, IC and its factors and the sub-dimensions of these factors can be identified, and the research model developed for relationships between factors of IC. The quantitative and qualitative performance by companies is a reliable, valid and available model based on YEM tests.

As a result of factor analysis made to identify dimensions of intellectual capital, it has been demonstrated that factor distributions range in accordance with the literature. As a result of the confirmatory factor analysis conducted, it has been demonstrated that IC is divided into three meaningful factors: SC, RC and HC. By measuring for the detection of the sub-dimensions of these three factors, what affects IC, and the level of the effects has been defined. HC constitutes IC with a coefficient of 0,93; SC with a coefficient of 0,95; and RC with a coefficient of 0,93.

Following the review of more detailed findings related to the results obtained, it has been demonstrated that SC is classified as a) corporate image and brand; b) intellectual property; c) information technologies; d) management philosophy; e) process, system and procedure; f) R&D and innovativeness; and g) organisational culture.

When we detail RC, one of three factors constituting intellectual capital, it has been demonstrated that RC is classified as a) customer care; b) supplier relations; c) network partner relations; d) investor/partner relations; and e) public relations.

When we detail HC, one of three factors constituting intellectual capital, it has been demonstrated that HC is classified as a) know-how and skill capital; b) motivation capital; c) innovativeness/adaptation capital; and d) employee social capital.

IC affects company performance positively. The IC variable explains that there is a 92 percent variance in firm performance. Organisational activity is crucial for intellectual capital. Organisational activity includes both qualitative and quantitative data. It has been demonstrated that the effect of qualitative performance is 0,84, while the effect of quantitative performance is 0,72. When we look at the effects of factors of IC on performance quantitatively and qualitatively, the most important is RC. It is demonstrated that the second most important factor is HC, and thethird is SC.

RC affects qualitative performance with a coefficient of 0,94 and quantitative performance with a coefficient of 0,60. HC affects qualitative performance with a coefficient of 0,92, and quantitative performance with a coefficient of 0,54. SC affects qualitative performance with a coefficient of 0,90 quantitative performance with a coefficient of 0.53.

When we look at all the dimensions together, RC becomes prominent as the most significant factor, with HC second. In terms of sub-dimensions, corporate image and brand become prominent as the most significant factor, R&D and innovativeness follow, and employee motivation is third.

The results of the study demonstrate that IC and its components have positive effects on both the qualitative and quantitative performance by firms. On the other hand, it could be argued that the effect of IC is more dominant in qualitative performance. In the research, qualitative performance refers to innovation performance, adaptation performance, operational performance and human resources performance. However, quantitative performance is measured in the firms' financial performance. It can therefore be assumed that the effects of IC and its components can be seen more prominently in a firm's qualitative performance.

References

AKPINAR, S. 2003. Entelektüel sermayenin işletmelerin performansi üzerindeki etkileri. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Kocaeli: T.C. Gebze Yüksek Teknoloji Enstitüsü Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü [ Links ].

ARIKAN, R. 2004. Araştirma teknikleri ve rapor hazirlama. Ankara: Asil Yayin. [ Links ]

BILGEN, B. 2001. Performans ölfme sistemlerinin incelenmesi. II. Ulusal Üretim Arajtirmalari Sempozyumu. Istanbul: Istanbul Teknik Üniversitesi Işletme Fakültesi. [ Links ]

BONTÍS, N. 1998. Intellectual capital: An exploratory study that develops, measures and models. Journal of Management History, 36(2):63-76. [ Links ]

BONTIS, N. 1999. Managing organizational knowledge by diagnosing intellectual capital: Framing and advancing the state of the field. International Journal of Technology Management, 18(5):433-462. [ Links ]

BONTIS, N. 2001. Assessing knowledge assets: A review of the models used to measure intellectual capital. International Journal of Management Reviews, 3(1):41-60. [ Links ]

BONTIS, N., KEOW, C., CHUA, W. & STANLEY, R. 2000. Intellectual capital and business performance in Malaysian industries. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1(1):85-100. [ Links ]

BROOKING, A. 1996. Intellectual capital. London: International Thompson Business Press. [ Links ]

BRUGGEN, A., VERGAUWEN, P. & DAO, M. 2009. Determinants of intellectual capital disclosure: Evidence from Australia. Management Decision, 47(2):233-245. [ Links ]

CHEN, M.C., CHENG, S.J. & HWANG, Y. 2005. An empirical Investigation of the relationship between intellectual capital and firms' market value and financial performance. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 6(2):159-176. [ Links ]

DZfNKOWSKi, R. 2000. The measurement and management of intellectual capital: An introduction. Management Accounting, 78(2):32-36. [ Links ]

EDVÍNSSON, L. 1997. Developing intellectual capital at Skandia. Long Range Planning, 30(3):366-373. [ Links ]

EDVÍNSSON, L. 2002. Corporate longitude. London: Financial Times Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

EDVÍNSSON, L. & MALONE, M.S. 1997. Intellectual capital: The proven way to establish your company's real value by finding its hidden brainpower. Harper Business, New York. [ Links ]

ERGÜN, E. 2003. Işletmelerdeki külturel ózelliklerin órgüt performansina etkisi uzerine bir uygulama. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Kocaeli: T.C. Gebze Yüksek Teknoloji Enstitüsü Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü [ Links ].

GARCÍA-ÁLVAREZ, M.T., MARfZ-PÉREZ, R.M. & ÁLVAREZ, M.T. 2011. Structural capital management: A guide for indicators. International Journal of Management & Information Systems (IJMIS), 15(3):41-52. [ Links ]

HUANG, C.C., LUTHER, R & TAYLES, M. 2007. An evidence-based taxonomy of intellectual capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 8(3):386-408. [ Links ]

KIM, D.Y. & KUMAR, V. 2009. A framework for prioritization of intellectual capital indicators in R&D. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 10(2):277-293. [ Links ]

KURŞUNMADEN, F. 2007. Değer mühendisliği açisindan işletmelerdeki entelektüel sermaye unsurlarinin analizi. Journal of Azerbaijani Studies, 10(3-4):40-58. [ Links ]

LÌAO, P.J., HUANG, C.H. & HSU, K.H. 2010. Indicators and standards for measuring intellectual capital of companies in the emerging industry: Exemplified by biopharmaceutical companies. International Journal of Services and Standards, 6(3-4):231-235. [ Links ]

LUTHY, D.H. 1998. Intellectual capital and its measurement. In Proceedings of The Asia Pacific Interdisciplinary Research in Accounting Conference (APIRA), Osaka, Japan, August:16-17. [ Links ]

MADÍTÍNOS, D., CHATZOUDES, D., TSAÍRÍDÍS, C. & THERÍOU, G. 2011. The impact of intellectual capital on firms' market value and financial performance. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 12(1):132-151. [ Links ]

MARR, B. 2004. Measuring and benchmarking intellectual capital. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 11(6):559-570. [ Links ]

MARR, B. 2005. Strategic management of intangible value drivers. Handbook of Business Strategy, 6(1):147-54. [ Links ]

MEHRALlAN, G.H., RAJABZADEH, A., SADEH, M.R. & RASEKH, H.R. 2012. Intellectual capital and corporate performance in the Iranian pharmaceutical industry. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 13(1):138-158. [ Links ]

MOON, Y.J. & KYM, H.G. 2006. A model for the value of intellectual capital. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 23(3):253-269. [ Links ]

MULAÌK, S.A. & MlLLSAP, R.E. 2000. Doing the four-step right. Structural Equation Modeling, 7(1): 36-73. [ Links ]

MUZAFFAR, H. 2011. Dinamik çevrede girişimci odaklilik, dinamik kabiliyetler ve işletme performansi arasindaki ilişki. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Ankara: Ankara Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü [ Links ].

NORDSTRÖM, K.A. & RÍDDERSTRÁLE, J. 2002. Funky business: Talent makes capital dance. London: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

OECD. 2007. OECD Insights human capital: How what you know shapes your life. Paris: OECD. [ Links ]

PETTY, R. & GUTHRlE, J. 2000. Intellectual capital literature review: Measurement, reporting and management. Journal of Intellectual Capital 1(2):155-176. [ Links ]

REHMAN, W., REHMAN, C.A. & ZAGÍD, A. 2011. Intellectual capital performance and its impact on corporate performance: An empirical evidence from the Modaraba sector of Pakistan. Australian Journal of Business and Management Research, 1(5):8-16. [ Links ]

ROOS, G. & ROOS, J. 1997. Measuring your company's intellectual performance. Long Range Planning, 30(3):413-426. [ Links ]

SAÌNT-ONGE, H. 1998. How knowledge management adds critical value to distribution channel management. Journal of Systemic Knowledge Management. [ Links ]

SEETHARAMAN, A., LOW, K.L.T. & SARAVANAN, A.S. 2004. Comparative justification on intellectual capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 5(4):522-539. [ Links ]

SELEMÍ, A., ASHOUR, A. & BONTIS, N. 2007. Human capital and organizational performance: A study of Egyptian software companies. Management Decision, 45(4):789-801. [ Links ]

STEWART, T.A. 1991. Brainpower. Fortune, 123. [ Links ]

SUBRAMANÍAM, M. & YOUNDT, M.A. 2005. The influence of intellectual capital on the types of innovative capabilities. Academy of Management Journal, 48(3):450-463. [ Links ]

SULLÍVAN, P.H. 2000. Value driven intellectual capital: How to convert intangible corporate assets into market value. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [ Links ]

SVElBY, K.E. 1998. Measuring intangibles and intellectual capital: An emerging standard. Available at: http://www.sveiby.com/articles/EmergingStandard.Html [accessed 2012-05-12]. [ Links ]

SVEÍBY, K.E. 2001. A knowledge-based theory of the firm to guide strategy formulation. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 2(4):344-358. [ Links ]

WANG, W.Y. & CHANG, C. 2005. Intellectual capital and performance in causal models: Evidence from the information technology industry in Taiwan. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 6(2):222-236. [ Links ]

YANG, J., WANG, J., WONG, C.W. & LAl, K.H. 2008. Relational stability and alliance performance in supply chain. Omega, 36(4):600-608. [ Links ]

YILMAZ, C., ALPKAN, L. & ERGUN, E. 2005. Cultural determinants of customer- and learning-oriented value systems and their joint effects on firm performance. Journal of Business Research, 58:1340-1352. [ Links ]

Accepted: October 2014