Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versão On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.18 no.1 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2222-3436/2015/v18n1a3

ARTICLES

Employee well-being, intention to leave and perceived employability: A psychological contract approach

Leoni van der Vaart; Bennie Linde; Leon de Beer; Marike Cockeran

WorkWell Research Unit, North-West University

ABSTRACT

Employability emerged as a "new psychological contract" that may have beneficial effects on both individual and organisational outcomes. The study set out to investigate the relationship between perceived employability and employee well-being on the one hand and perceived employability and employees' intention to leave on the other. The role of the state of the psychological contract, in terms of retaining employable employees while improving their well-being, was also investigated. Cross-sectional data were obtained from employees representing various organisations (N = 246). Contrary to expectations, structural equation modelling (SEM) indicated no significant relationship between perceived employability and well-being. Perceived employability was a significant predictor of employees' intention to leave the organisation. Results also indicated that the state of the psychological contract does not moderate the relationship between perceived employability and employee well-being and their intention to leave, respectively. The study stresses the importance of fulfilling promises made to employees ensuring that promises are fair and continuing to fulfil promises. The importance of interventions on individual-level, to enhance well-being in the workplace, is also emphasised.

Key words: employability, employee well-being, intention to leave, psychological contract

1 Introduction

Lately there has been renewed interest in employability research and appreciation of its importance for the well-being of the individual as well as the success of the organisation (Fugate, Kinicki & Ashforth, 2004; Van Dam,2004; Wittekind, Raeder & Grote, 2010).Employability is a concept that emerged in the 1990s in response to employees' perceptions that they cannot count on their employer to ensure job security (Baruch, 2001). Job security is being replaced with employability security, which means that employees derive security from being employable (Forrier & Sels, 2003 a). According to Elman and O'Rand (2002) and De Grip, Van Loo and Sanders (2004), highly employable employees are likely to be top performers. This paradox raises the question of how organisations can reduce the likelihood of undesirable turnover whilst utilising employ-ability to boost employee well-being and organisational performance (De Cuyper, Van der Heiden & De Witte, 2011). The psychological contract may provide an answer to the above question. De Cuyper, Van der Heijden et al. (2011) argue that employability will relate to favourable individual and organisational outcomes, if employees perceive their psychological contracts to be fair. They base this assumption on the notion of "contract replicability". Ng and Feldman (2008) demonstrated that employees will remain with a particular organisation if they believe that the psychological contract will not be replicated in another organisation and those employees will simultaneously experience more job and life satisfaction.

Despite the increased interest in employability, there are currently still several gaps in research. Rothwell, Jewell and Hardie (2009) place the emphasis on what employability actually means to employees in the context of their experiences, their aspirations and their perceptions of their ability to compete in the external labour market. De Cuyper, Van der Heijden et al. (2011) and Nauta, Van Vianen, Van der Heijden, Van Dam and Willemsen (2009) are of the opinion that very few empirical studies have proved the relationship between employability and intention to leave. Berntson and Marklund (2007) also point out that little research has been carried out with a specific focus on the influence of employability on employee health and well-being -this is confirmed by De Cuyper, Bernhard-Oetell, Berntson, De Witte and Alarco (2008) as well as De Cuyper, Mauno, Kinnunen and Mákikangas (2011). This study also aims to extend previous research by De Cuyper, Van der Heijden et al. (2011), in which only psychological contract entitlements (promises) were investigated, in other words psychological contract content, by focusing on the state of the psychological contract. Guest (1998) describes the state of the psychological contract as an important precursor of employee behaviour and attitudes, beyond the variance explained by the content of the psychological contract.

2 Literature review

2.1 Perceived employability, employee well-being and intention to leave

Employability is defined by Van der Heijde and Van der Heijden (2006:453) as "the continuous fulfilling, acquiring, or creating of work through the optimal use of one's competences". Perceived employability is defined as an employee's perception of the possibility of finding a new and similar job (Berntson, Sverke & Marklund, 2006; Berntson & Marklund, 2007) with the current employer or another organisation (De Cuyper, Van der Heijden et al., 2011). This definition is consistent with more general definitions and it reflects a more subjective approach in that it focuses on the employee's perception (De Cuyper, Van der Heijden et al., 2011). During periods of major organisational change, the employee's perception of employability matters more than the objective employability (Berntson et al., 2006). Employability should lead to good health, if an employee perceives him- or herself as mobile within or outside the current organisation. It enables employees to move around in order to find a better work environment and, even if they do not change jobs, it gives them a sense of being able to cope with current circumstances; a privilege that low-employability employees may nothave (Berntson & Marklund, 2007).

Employability is also indicative of the new psychological contract that exists between employees and employers (Hallier, 2009). Highly employable employees feel that they are capable of dealing with current and future developments, including the changes in the psychological contract, and this is likely to enhance their well-being (De Cuyper et al., 2008). Employee well-being refers to the physical, mental and emotional well-being of employees and assumes that a positive evaluation of one's work experience is conducive to one's well-being (Cartwright & Cooper,2009; Currie, 2003). Guest, Isaksson and DeWitte (2010) used indicators of satisfaction at work and in life, mental health (irritation, anxiety and depression) and work-life balance to measure work-related well-being as an outcome variable in their psychological contract research. Although employability can be beneficial to the organisation, the positive relationship between employability and intention to leave remains a concern for the employer.

According to Larson and Fukami (1985), perceived ease of movement is seen as a core predictor of actual turnover. De Cuyper et al.(2008) and Fugate et al. (2004) confirm thatperceived ease of movement- by implication perceived employability - motivate employees to explore alternative employment options, which is considered the first step towards forming an intention to leave. An employee's intention to leave the organisation is a strong predictor of actual turnover (Vandenberg & Nelson, 1999). In a work environment characterised by feelings of insecurity, employees may feel that their employers cannot guarantee them on-going employment and they may consequently take charge of the situation by making themselves more employable. They therefore no longer feel any loyalty towards the organisation and would leave the organisation in pursuit of better opportunities, since they feel they cannot rely on the employer (Benson, 2006; De Cuyper & De Witte, 2008). If employees believe they can leave the organisation without substantial losses they are more inclined to resign (De Cuyper, Mauno et al., 2011). Researchers have found a positive relationship between perceived employability and intention to leave (Berntson, Näswall & Sverke, 2010; De Cuyper, Van der Heijden et al., 2011), but De Cuyper, Mauno et al. (2011) point out that this relationship has been found to be weak overall.

2.2 The role of the psychological contract in retaining highly employable employees

Coyle-Shapiro and Neuman (2004) and Rousseau (2001) maintain that employability management implies a new mutual psychological contract; a responsibility that Van der Heijden and Bakker (2011) ascribe to both employees and employers. Employees regard employability as a promise by the employer (Craig, Kimberly & Bouchikhi,2002; Waterman, Waterman & Collard, 1994).A promise made by the employer is generally referred to as the content of the psychological contract (CIPD, 2006; Rousseau, 1995). Therefore, employees perceive it as a fulfilment of the psychological contract if employability is enhanced by the employer and, in turn, they will be loyal to the organisation (De Cuyper, Van der Heijden et al., 2011). According to the Social Exchange Theory (SET), individuals will establish and maintain a relationship, if they perceive this relationship to be mutually beneficial. Individuals therefore enter into a relationship where they expect benefits to be exchanged irrespective of normative obligations (Zafirovsky, 2005).

Ng and Feldman (2008) found that employees experienced an enhanced desire to stay in an organisation with which they believe they have a contract that cannot be replicated in another organisation. De Cuyper, Van der Heijden et al. (2011) conclude that the interaction between perceived employability and psychological contract entitlements is significant for job and life satisfaction in the event of few entitlements. They did not find the interaction effect to be significant for turnover intention. This study focuses on the state of the psychological contract and expands the concept of psychological contract content. The state of the psychological contract has broadened the psychological contract construct to include the core elements (trust and fairness) of the traditional employment relationship and focuses less on the promises made and more on delivery (Guest & Conway, 2004). Studies focusing on the evaluation of the state of the psychological contract contribute to explanatory research rather than descriptive research enabling researchers to predict certain variables related to employees' attitudes, behaviour and well-being (Gracia, Silla, Peiró & Fortes-Ferreira, 2007).

3 Study objective and hypotheses

The objective of this paper was to investigate the relationship between the state of the psychological contract (as perceived by the employee), perceived employability, employee well-being and intention to leave; and to determine whether the psychological contract (as perceived by the employee) and perceived employability interact in such a way that perceived employability relates positively to employee well-being and negatively to intention to leave under the conditions of fulfilment, trust and fairness among employees.

The following hypotheses were set for this study, based on the discussion above:

Hypothesis 1a: There is a positive relationship between perceived employability and employee well-being.

Hypothesis 1b: There is a positive relationship between perceived employability and intention to leave.

Hypothesis 2a: State of the psychological contract moderates the relationship between the perceived employability and employee well-being.

Hypothesis 2b: State of the psychological contract moderates the relationship between the perceived employability and employee's intention to leave.

4 Method

4.1 Research design and participants

This study follows a quantitative, cross-sectional research approach. Primary data collection was performed and data was analysed by means of a correlational approach. A convenience sample of respondents was used (N = 246). The majority of the respondents were male (n = 151; 61 per cent). Forty four percent (n = 108) of the respondents had a higher educational background (i.e. education beyond secondary school level) and 37 per cent (n = 91) were in possession of Grade 12 certificates (i.e. education at secondary school level). Most participants were employed on permanent contracts (n = 229; 93 per cent). The mean age of the participants was 39 years (SD = 10.54) and their mean organisational tenure was eight years (SD = 9.04). The participants ranged from entry-level employees to top management. Tabachnick and Fidell (2013) state that a sample size of between 200 and 300 can be perceived as "fair" for structural equation modelling.

The data for the study was obtained through a combination of multi-stage non-probability sampling techniques, namely convenience and snowball sampling. During the first stage participants who were easiest to reach were asked to complete the questionnaire. Participants were then asked to identify other relevant members of the working population who were able to participate in the study (Olckers, Buys& Grobler, 2010; Welman, Kruger & Mitchell,2005). The method was repeated until a representative sample of participants had completed the questionnaire. The convenience sample consisted of 66 per cent (n = 163) respondents from a cable manufacturing organisation and the snowball sample consisted of 34 per cent (n = 83) respondents from various industries in the province of Gauteng in South Africa. These employees represented the automotive, engineering, education, finance, media, metals and mining, nursing, police and retail industries.

4.2 Measuring instruments

Three measure of the PSYCONES questionnaire were used to evaluate the state of the psychological contract, employee well-being and intention to leave. The psychological contract measure was developed for thepurpose of the PSYCONES project (De Cuyper, Van Der Heijden & De Witte, 2011),based on factor analyses of earlier instruments (Isaksson et al., 2003). The assumption of tau equivalence (required for alpha coefficients) is violated when latent variables scores are calculated, therefore reliabilities (ω) for the scales were computed by means of composite (omega) reliabilities (Raykov, 2009; Wang & Wang, 2012). According to the 0.70 guideline of Wang and Wang (2012), all the constructs were reliable.

Psychological contract

To determine whether employees had a positive perception of their psychological contract, three aspects of the psychological contract were evaluated: content (employer and employee obligations), perceived fulfillment and the state of the psychological contract. Regarding employer obligations, three dimensions are covered by the scale, namely transactional aspects, career prospects and opportunity to influence decision-making. Linde and Schalk (2008) established that these three dimensions can be grouped into one factor through exploratory factor analysis. Employer obligations were measured by means of 15 items (e.g. "Has your organisation promised or made a commitment to provide you with interesting work"). The items are scored on a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 = "No" to 5 = "Yes, and promise fully kept". The omega reliability for the scale was acceptable (ω = 0.93).

Employee obligations (one dimension) were measured using 16 items (e.g. "Have you promised or committed yourself to show loyalty to the organisation"). The items are scored on a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 = "No" to 5 = "Yes, and promise fully kept". The omega reliability for the scale was acceptable (ω =0.86). Referring to both employer obligations and employee obligations, "No" (0) and "Yes" (1-5) refer to the measurement of the content of the psychological contract. The scale from 1-5 refers to the fulfilment of the psychological contract, after the content of the psychological contract has been established. In this paper we refer to the state of the psychological contract, which includes the fulfilment and state of the psychological contract. Therefore, the items which refer to an exclusion of the contents ("No") were not included in the statistical analyses. The items that were used to measure the state of the psychological contract were based on the trust in management and justice. State of the psychological contract was evaluated using seven items (e.g. "Do you feel you are fairly paid for the work you do"). The items are scored on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = "not at all" to 5 = "totally". The omega reliability for the scale was acceptable (ω = 0.91).

Intention to leave

Intention to leave was measured using four items (e.g. "These days, I often feel like quitting"). The items are scored on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = "strongly disagree" to 5 = "strongly agree". The omega reliability for the scale was acceptable (ω = 0.72).

Employee well-being

Employee well-being was measured on five scales: job satisfaction, satisfaction with life, mood (positive and negative affective well-being), positive work-home interference, and irritation. Job satisfaction was measured using four items (e.g. "I find enjoyment in my work"). The items are scored on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = "strongly disagree" to 5 = "strongly agree". The omega reliability for the scale was acceptable (ω = 0.76). Satisfaction with life is measured using six items (e.g. "How satisfied do you currently feel about your life in general"). The items are scored on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = "very dissatisfied" to 7 = "very satisfied". The omega reliability for the scale was acceptable (ω =0.84).

For affective well-being, two dimensions are covered by the scale, namely work-related depression and work-related anxiety. Affective well-being was measured using 10 items ("In the past few weeks, how often have you felt uneasy regarding your work"). The items are scored on a five-point frequency-rating scale ranging from 1 = "rarely or never" to 5 = "very often or always". The omega reliability for the scales was 0.83 for positive affect and 0.80 for negative affect). Positive work-home interference was measured using three items (e.g. "How often does it happen that you manage your time at home more efficiently as a result of the way you do your job"). The items are scored on a five-point frequency-rating scale ranging from 1 = "rarely or never" to 5 = "very often or always". The omega reliability for the scale was acceptable (ω = 0.81). Irritation was measured using eight items (e.g. "I get angry quickly"). The items are scored on a five-point frequency-rating scale ranging from 1 = "strongly disagree" to 5 = "strongly agree". The omega reliability for the scale was acceptable (ω = 0.86).

Perceived employability

Perceived employability was measured using four items developed by De Witte (1992). It has been applied successfully in different employment settings and countries (Guest et al., 2010). Respondents rate their agreement with the following items: "I am optimistic that I would find another job, if I looked for one", "I will easily find another job if I lose this job", "I could easily switch to another employer, if I wanted to", and "I am confident that I could quickly get a similar job". All the items are rated on a five-point frequency-rating scale ranging from 1 = "strongly disagree" to 5 ="strongly agree". The omega reliability for the scale was acceptable (ω = 0.85).

4.3 Statistical analysis

To investigate the current research Mplus 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012) was used. Mplus has the ability to implement the maximum likelihood robust version (MLR) in latent variable modelling which is robust against non-normality of data (presents more accurate standard errors). The level for statistical significance was set at the 95 percent level (p<0.05). Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were used to specify the relationships between the variables. Effect sizes were used to determine the practical significance of the results (Steyn, 2002). Cutoff points of r>0.30 (medium effect) and r>0.50 (large effect) were set for determining the practical significance of the correlation coefficients (Cohen, 1977). Kline (2010) suggests a two-step model building approach to structural equation modelling (SEM). Firstly, in order to test the factorial validity of the measurement model confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was implemented. The measurement model was validated by obtaining estimates of the parameters of the models and by determining whether the model itself provides a good fit to the data (Byrne, 2010). It is important to note that competing measurement models could not be tested as with MLR estimation, only nested models can be tested against each other and the chi-square and fit indices cannot be used to compare models in the regular way.

The structural model was evaluated next by adding the regression relationships in line with the hypotheses. The following indices were used to assess the model fit: Root Means Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), incremental fit indices, including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). CFI and TLI values higher than 0.90 are considered acceptable. RMSEA values lower than 0.08 indicate acceptable fit between the model and the data (Hair, Black, Babin & Andersen, 2010). To investigate the potential interaction effect of employability and state of the psychological contract on well-being and intention to leave, the XWITH function was used in Mplus to create the moderating variables; and well-being and intention to leave was then regressed on this interaction term. Furthermore, to investigate the indirect effect of well-being between employability and intention to leave and between state of the psychological contract and intention to leave, bootstrapping was used with a request for 5000 resampling draws.

5 Results

5.1 Measurement model

An initial model, which used all of the observed indicators to estimate a second-order latent variable for well-being in an overall measurement model, did not fit the data well. Therefore, a second model with the well-being construct was estimated using parcels of its theoretical constructs, i.e. job satisfaction, irritation, positive home-work interference, satisfaction with life and affect (positive and negative affect). Positive and negative affect had to be split from a general parcel as parcelling can only be accurately used if one is sure of the unidimensionality of the items. If they were clustered together this would violate that assumption. This was done similarly for the employee and employer obligation constructs. All reversed items were reversed coded to ensure accuracy of the parcels. Perceived employability and intention to leave were estimated by their corresponding observed indicators. This resulted in a good fitting model: X2 = 675.131 (df = 396, p<0.001), SRMR = 0.06, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.92, and TLI = 0.92.

5.2 Structural model

Correlations between the constructs are reported in Table 1.

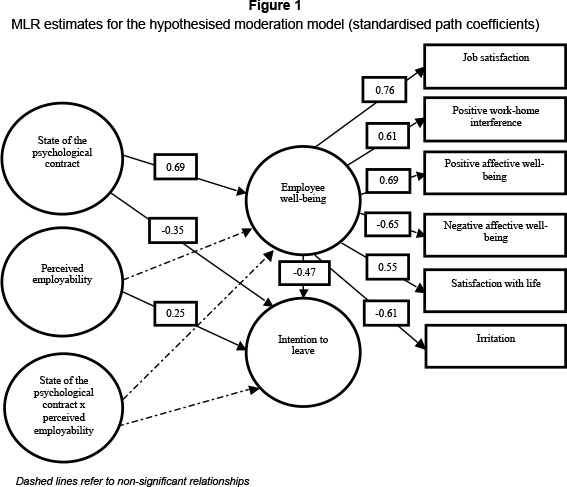

The structural model, as depicted in Figure 1, evaluated the hypothesised regressions and whether the state of the psychological contract moderated the relationship between perceived employability and employee well-being and intention to leave, respectively. The hypothesised model, as depicted in Figure 1, provided an adequate fit to the data, SRMR =0.06, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.92, and TLI = 0.92.

Table 2 shows the standardised regression coefficients estimated by Mplus for the structural model.

The first hypothesis was concerned with possible principal effects of perceived employability. The moderation model indicated that contrary to Hypothesis 1a, perceived employ-ability did not help to predict employee well-being (β = -0.01, p>0.05), rejecting the hypothesis. Perceived employability was found to significantly predict intention to leave (β = 0.24, p<0.001) consistent with Hypothesis 1b. Finally, the interaction term between perceived employability and the state of the psychological contract did not significantly predict employee well-being (β = 0.01, p>0.05) or intention to leave (β = -0.12, p>0.05).

Hypotheses 2a and 2b were not supported. The indirect effect of the state of the psychological contract was evaluated using bootstrapping to construct two-sided bias-corrected 95 per cent confidence intervals (CIs). Regarding the indirect effects, the 95 per cent CIs for intention to leave did not include zero. The state of the psychological contract impacts intention to leave via well-being. A substantial amount of variation in the model is explained by the relationships depicted in the model. The model accounts for 63 per cent of the variance in intention to leave and 46 per cent of the variance in employee well-being, providing more empirical support for the model's fit.

6 Discussion

6.1 Main findings

Various researchers have indicated the need for exploring the consequences of employ-ability for both employees and the organisation (De Cuyper et al., 2008; Fugate et al., 2004; Wittekind et al., 2010). Therefore, the aim of this research was to investigate the predictive ability of perceived employability in terms of employee well-being and intention to leave. According to De Cuyper et al. (2008), the conditions under which moderation mechanisms occur should also be explored. The second aim of the research was to determine whether the psychological contract and perceived employability interact in such a way that perceived employability relates positively to employee well-being and negatively to intention to leave under the conditions of fulfilment, trust and fairness amongst employees. The researchers expanded on previous research by evaluating a comprehensive structural equation model which provides simultaneous testing of the complicated relationship between perceived employability, employee well-being and intention to leave as well as the state of the psychological contract.

Contrary to what was expected, structural equation modelling indicated that perceived employability is not significantly related to employee well-being. Silla, De Cuyper, Gracia, Peiró and De Witte (2009) also found that perceived employability was not significantly related to employee well-being (psychological distress and life satisfaction). De Cuyper, Van der Heijden et al. (2011) also concluded that perceived employability is not significantly related to job satisfaction. A possible explanation for this is that employees still rely on "traditional" job security (Silla et al., 2009), as was confirmed by the statistically significant relationship in the structural model between the state of the psychological contract and employee well-being. The majority of the participants were permanent workers and according to Millward and Brewerton (2000), permanent employees differ from temporary workers in their view of the psychological contract. De Cuyper and De Witte (2006, 2007) are of the opinion that permanent workers still expect a secure job in return for loyalty whereas job insecurity is the norm for temporary workers. In other words, perceived employability may predict employee well-being in the case of "boundaryless careers" (Forrier & Sels, 2003b; Kluytmans & Ott,1999; Rajan, 1997), which is more likely to be the reality for temporary employees. The human capital theory postulates that employ-ability may be one way for individuals to improve their attractiveness to potential employers (Berntson et al., 2006), and may serve as a coping mechanism for temporary employees. However, De Cuyper, Van der Heijden et al. (2011) state that employee well-being may depend on conditions that are currently specific to the job and may not be dependent on what employees believe about their future job opportunities or issues related to the career, the labour market or their potential.

Structural equation modelling confirmed the positive relationship between perceived employability and an employee's intention to leave the organisation. Previous studies also found a significant positive relationship (De Cuper, Van der Heijden et al., 2011). Van Vianen, Feij, Krausz and Taris (2003) describe push and pull as the two motives for leaving an organisation. The results confirmed that perceived employability serves as a pull factor. However, the structural model also indicated that employee well-being is a better predictor of employees' intention to leave than perceived employability. Interventions should focus on improving employees' well-being. This is important in view of the positive influence of well-being on performance and turnover (Page & Vella-Brodrick, 2009). One way of achieving this is through various positive psychology interventions (Seligman, Steen, Park & Peterson, 2005). The findings did not align with Hypothesis 2 either. The state of the psychological contract did not moderate (a) the relationship between perceived employability and employee well-being and (b) the relationship between perceived employability and employees' intention to leave. The inability of the state of the psychological contract to moderate the relationship between perceived employability and employee well-being might be ascribed to the absence of a significant relationship between perceived employability and employee well-being, for possible reasons that were explained earlier.

The absence of a moderating effect on the state of the psychological contract between perceived employability and employees' intention to leave suggests that perceived ease of movement will increase employees' intention to leave, regardless of the nature of the relationship between the employer and employee. This conclusion, is too simplistic, however. Results indicated that the psychological contract is an important factor in an employee's intention to leave, and that it operates indirectly through employee well-being. In the current study, the state of the psychological contract significantly predicted employee well-being. This confirms previous findings by both Gracia et al. (2007) and Parzefall and Hakanen (2008). In turn, in line with previous studies (Page & Vella-Brodrick, 2009) employee well-being significantly predicted employees' intention to leave.

Baruch (2001) stresses that organisations should provide their people with employability but also commitment. He also warns that an exclusive focus on employability might create a lose-win situation where employable (talented) employees will leave the organisation for more attractive alternatives. Kalshoven and Boon (2012) also maintain that HR practices that encourage employee involvement and commitment will improve employee well-being. The current study supports this notion by demonstrating why it is important to ensure the positive evaluation of the psychological contract. Ensuring that employees' psychological contracts are fair, and that organisations continue to fulfill them, is an important mechanism by which human resource departments improve employee well-being in order to retain employees. Conway and Briner (2009) emphasise the fact that organisations shape employees' psychological contract in three ways: through their human agents, such as managers, who communicate messages to the employees; through policies and practices (especially human resources practices); and through employment contracts. According to Handley, Sturdy, Fincham and Clark (2006), managers can improve trust by providing recognition, by being sensitive to subordinates' needs and concerns and by creating effective communication channels. Special attention should be paid to the way managers communicate messages as well as to the content of these messages.

7 Limitations and recommendations

Several limitations of this study should be taken into account when the current results are interpreted. Possibly the most limiting factor in this study was the cross-sectional design; by implication no causal inferences may be drawn. Self-report surveys from employees were the only source of information about predictor and outcome variables. Common method variance in which correlations between predictors and outcome variables are inflated is a likely consequence when only one source is used to obtain data (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee & Podsakoff, 2003). In this study, employees' perception regarding concepts like state of the psychological contract, employee well-being and intention to leave were evaluated and therefore self-reports are deemed appropriate for measuring these concepts(Rousseau, 1995; Freese & Schalk, 2008). As aresult of the relatively small sample size, the geographic restriction of the study population and the sampling procedure, there are possible limitations to the generalisability of the findings. However, the aim of the study was to establish relationships between the variables under study and not to generalise findings.

Demographic variables were not included as control variables in the regression analysis. This presents a serious limitation, as other dispositional factors may relate to employee well-being and intention to leave, such as level of education or income, age or race. The majority of participants in the sample have not obtained a post-school qualification. Berntson et al. (2006) found a positive relationship between educational level and perceived employability and because the majority of the participants were not highly employable according to objective standards, the relationships may appear weaker and/or not significant. The variance explained by perceived employability was quite low for intention to leave. The study measured perceived employability and intention to leave by means of a small number of items. According to Silla et al. (2009), this may restrict the sample variation, with the result that a small percentage of variance is explained.

A promising route for future research would be to explore the role of employability as a moderator. Researchers have begun to investigate the role of perceived employability as moderator between job stressors and well-being (Bussing, 1999; Mohr, 2000; Silla et al., 2009). In view of the positive relationship between perceived employability and intention to leave, future studies should investigate other factors that may moderate the relationship. De Cuyper, Mauno et al. (2011) concluded the relationship between perceived employability and intention to leave is indirect and that it is important to investigate further moderators and/or mediators. The hypothesised relationships may also be different in a sample of temporary workers, owing to differences in psychological contracts as discussed above. Job insecurity -which is believed to be an integral part of temporary employment - suggests that perceived employability may be more important for these individuals and for their well-being (De Cuyper, Notelaers & De Witte, 2009; De Cuyper, De Witte, Kinnunen & Nätti, 2010).

Future research could focus on examining the relationship between the variables in a sample of temporary workers, with permanent employees as a reference group. Contract preferences are reported to be an even more important predictor of employees' reactions than contract type (Connelly & Gallagher, 2004; Isaksson & Bellagh, 2002). According to Kinnunen, Mákikangas, Mauno, Siponen & Nätti (2011), contract preferences refer to whether an employee's temporary employment is voluntary or involuntary. They also believe that employees occupying temporary positions involuntarily want to be employed permanently by an organisation and therefore their psychological contract may be similar to those of permanent employees (Kinnunen et al., 2011). Future research could investigate the model proposed in this study by taking into account contract type (permanent or temporary) and preferences (voluntary or involuntary) when comparing groups.

References

BARUCH, Y. 2001. Employability: A substitute for loyalty? Human Resource Development International, 4(4):543-566. [ Links ]

BENSON, G.S. 2006. Employee development, commitment and intention to turnover: A test of "employability" policies in action. Human Resource Management Journal, 16(2):173-192. [ Links ]

BERNTSON, E. & MARKLUND, S. 2007. The relationship between perceived employability and subsequent health. Work & Stress, 21(3):279-292. [ Links ]

BERNTSON, E., NÀSWALL, K. & SVERKE, M. 2010. The moderating role of employability in the association between job insecurity and exit, voice, loyalty and neglect. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 32(2):215-230. [ Links ]

BERNTSON, E., SVERKE, M. & MARKLUND, S. 2006. Predicting perceived employability: Human capital or labour market opportunities? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 27(2):223-244. [ Links ]

BÜSSING, A. 1999. Can control at work and social support moderate psychological consequences of job insecurity? Results from a quasi-experimental study in the steel industry. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(2):219-242. [ Links ]

BYRNE, B.M. 2010. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming (2nd ed.) Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

CARTWRIGHT, S. & COOPER, G.L. (eds.) 2009. The Oxford handbook of organizational well-being. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

CIPD. 2006. Psychological contracts across employment situations: Final report. Available at: http://cordis.europa.eu/documents/documentlibrary/100123961EN6.pdf [accessed 2011-04-02]. [ Links ]

COHEN, D. 1977. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (rev. ed.) Orlando: Academic Press. [ Links ]

CONNELLY, C.E. & GALLAGHER, D.G. 2004. Emerging trends in contingent work research. Journal of Management, 30(6):959-983. [ Links ]

CONWAY, N. & BRINER, R.B. 2009. Fifty years of psychological contract research: What do we know and what are the main challenges. In G.P. Hodgkinson & J.K. Ford (eds.) International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, (24:71-130). West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

COYLE-SHAPIRO, J.A.M. & NEUMAN, J.H. 2004. The psychological contract and individual differences: The role of exchange and creditor ideologies. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64:150-164. [ Links ]

CRAIG, E., KIMBERLY, J. & BOUCHIKHI, H. 2002. Can loyalty be leased? Harvard Business Review, 80(9):24. [ Links ]

CURRIE, D. 2003. Managing employee well-being. London: Spiro Press. [ Links ]

DE CUYPER, N., BERNHARD-OETELL, C., BERNTSON, E., DE WITTE, H. & ALARCO, B. 2008. Employability and employees' well-being: Mediation by job insecurity. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57(3) 488-509. [ Links ]

DE CUYPER, N. & DE WITTE, H. 2006. The impact of job insecurity and contract type on attitudes, well-being and behavioural reports: A psychological contract perspective. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79(3):395-409. [ Links ]

DE CUYPER, N. & DE WITTE, H. 2007. Job insecurity in temporary versus permanent workers: Associations with well-being, attitudes and behaviour. Work & Stress, 21(1):65-84. [ Links ]

DE CUYPER, N. & DE WITTE, H. 2008. Job insecurity and employability among temporary workers: A theoretical approach based on the psychological contract. In K. Naswall, J. Hellgren& M. Sverke (eds.) The individual in the changing working life, (88-107). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

DE CUYPER, N., DE WITTE, H., KINNUNEN, U. & NÀTTI, J. 2010. Job insecurity and employability and well-being among Finnish temporary and permanent employees. International Studies of Management & Organization, 40(1):57-73. [ Links ]

DE CUYPER, N., MAUNO, S., KINNUNEN, U. & MÀKIKANGAS, A. 2011. The role of job resources in the relation between perceived employability and turnover intention: A prospective two-sample study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 78:253-263. [ Links ]

DE CUYPER, N., NOTELAERS, G. & DE WITTE, H. 2009. Job insecurity and employability in fixed-term contractors, agency workers, and permanent workers: Associations with job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(2):193-205. [ Links ]

DE CUYPER, N., VAN DER HEIJDEN, B.I.J.M. & DE WITTE, H. 2011. Associations between perceived employability, employee well-being, and its contribution to organisational success: A matter of psychological contracts? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(7):1486-1503. [ Links ]

DE GRIP, A., VAN LOO, J. & SANDERS, J. 2004. The industry employability index: Taking account of supply and demand characteristics. International Labour Review, 143(3):211-233. [ Links ]

DE WITTE, H. 1992. Langdurigwerklozen: Tussenoptimisten en teruggetrokkenen [The long-term unemployed: Between optimism and resignation]. [ Links ] Leuven: HIVA.

ELMAN, C. & O'RAND, A.M. 2002. Perceived job insecurity and entry into work-related education and training among adult workers. Social Science Research, 31:49-76. [ Links ]

FORRIER, A. & SELS, L. 2003a. Temporary employment and employability: Training opportunities and efforts of temporary and permanent employees in Belgium. Work, Employment and Society, 17(4):641-666. [ Links ]

FORRIER, A. & SELS, L. 2003b. The concept employability: A complex mosaic. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, 3(2):102-124. [ Links ]

FUGATE, M., KINICKI, A.J. & ASHFORTH, B.E. 2004. Employability: A psychosocial construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65:14-38. [ Links ]

FREESE, C. & SCHALK, R. 2008. How to measure the psychological contract? A critical criteria-based review of measures. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(2):269-286. [ Links ]

GRACIA, F.J., SILLA, I., PEIRÓ, J.M. & FORTES-FERREIRA, L. 2007. The state of the psychological contract and its relation to employees' psychological health. Psychology in Spain, 11(1):33-41. [ Links ]

GUEST, D.E. 1998. Is the psychological contract worth taking seriously? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19:649-664. [ Links ]

GUEST, D.E. & CONWAY, N. 2004. Employee well-being and the psychological contract: A report for the CIPD. London: CIPD. [ Links ]

GUEST, D.E., ISAKSSON, K. & DE WITTE, H. 2010. Employment contracts, psychological contracts and worker well-being: An international study. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

HAIR, J.F., BLACK, W.C., BABIN, B.J. & ANDERSEN, R.E. 2010. Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. [ Links ]

HALLIER, J. 2009. Rhetoric but whose reality? The influence of employability messages on employee mobility tactics and work group identification. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(4):846-868. [ Links ]

HANDLEY, K., STURDY, A., FINCHAM, R. & CLARK, T. 2006. Within and beyond communities of practice: Making sense of learning through participation, identity and practice. Journal of Management Studies, 43(3):641-653. [ Links ]

ISAKSSON, K. & BELLAGH, K. 2002. Health problems and quitting among female "temps". European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 11(1):27-45. [ Links ]

ISAKSSON, K., BERNHARD, C., CLAES, R., DE WITTE, H., GUEST, D., KRAUSZ, M., MOHR, G., PEIRÓ, J.M. & SCHALK, R. 2003. Employment contracts and psychological contracts in Europe: Results from a pilot study. Available at: http://www.ekhist.uu.se/Saltsa/Saltsa_pdf/2003_6_Empl.contracts_Rep2003_01.pdf [accessed 2011-05-05]. [ Links ]

KALSHOVEN, K. & BOON, C.T. 2012. Ethical leadership, employee well-being, and helping: The moderating role of human resource management. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 11(1):60-68. [ Links ]

KINNUNEN, U., MÄKIKANGAS, A., MAUNO, S., SIPONEN, K. & NÄTTI, J. 2011. Perceived employability: Investigating outcomes among involuntary and voluntary temporary employees compared to permanent employees. Career Development International, 16(2):140-160. [ Links ]

KLINE, R.B. 2010. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3nd ed.) New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

KLUYTMANS, F. & OTT, M. 1999. Management of employability in the Netherlands. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(2):261-272. [ Links ]

LARSON, E.W. & FUKAMI, C.V. 1985. Employee absenteeism: The role of ease of movement. Academy of Management Journal, 28(2):464-471. [ Links ]

LINDE, B.J. & SCHALK, M.J.D. 2008. Influence of pre-merger employment relations and individual characteristics on the psychological contract. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(2):305-320. [ Links ]

MILLWARD, L.J. & BREWERTON, P.M. 2000. Psychological contracts: Employee relations for the twenty-first century. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (eds.) International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, (15:1-61). West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

MOHR, G.B. 2000. The changing significance of different stressors after the announcement of bankruptcy: A longitudinal investigation with special emphasis on job insecurity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(3):337-359. [ Links ]

MUTHÉN, L.K. & MUTHÉN, B.O. 1998-2012. Mplus user's guide (6th ed.) Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [ Links ]

NAUTA, A., VAN VIANEN, A., VAN DER HEIJDEN, B., VAN DAM, K. & WILLEMSEN, M. 2009. Understanding the factors that promote employability orientation: The impact of employability culture, career satisfaction, and role breadth self-efficacy. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82:233251. [ Links ]

NG, T.W.H. & FELDMAN, D.C. 2008. Can you get a better deal elsewhere? The effects of psychological contract replicability on organizational commitment over time. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73:268-277. [ Links ]

OLCKERS, C., BUYS, M.A. & GROBLER, S. 2010. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Multi-Dimensional Emotional Empathy Scale in the South-African context. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(1), Art.#856. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajipv36i1.856 [accessed 2012-06-10]. [ Links ]

PARZEFALL, M. & HAKANEN, J. 2008. Psychological contract and its motivational and health-enhancing properties. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(1):4-21. [ Links ]

PAGE, K.M. & VELLA-BRODRICK, D.A. 2009. The "what", "why" and "how" of employee well-being: A new model. Social Indicators Research, 90:441-458. [ Links ]

PODSAKOFF, P.M., MACKENZIE, S.B., LEE, J.Y. & PODSAKOFF, N.P. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5):879-903. [ Links ]

RAJAN, A. 1997. Employability in the finance sector: Rhetoric vs. reality. Human Resource Management Journal, 7(1):67-78. [ Links ]

RAYKOV, T. 2009. Evaluation of scale reliability for unidimensional measures using latent variable modeling. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 42(3):223-232. [ Links ]

ROTHWELL, A., JEWELL, S. & HARDIE, M. 2009. Self-perceived employability: Investigating the responses of post-graduate students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75:152-161. [ Links ]

ROUSSEAU, D.M. 1995. Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

ROUSSEAU, D.M. 2001. Schema, promise and mutuality: The building blocks of the psychological contract. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 74:511-541. [ Links ]

SELIGMAN, M.E.P., STEEN, T.A., PARK, N. & PETERSON, C. 2005. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5):410-421. [ Links ]

SILLA, I., DE CUYPER, N., GRACIA, F.J., PEIRÓ, J.M. & DE WITTE, H. 2009. Job insecurity and well-being: Moderation by employability. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10:739-751. [ Links ]

STEYN, H.S. 2002. Practically significant relationships between two variables. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 28(3):10-15. [ Links ]

TABACHNICK, B.G. & FIDELL, L.S. 2013. Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.) Needham Heights: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

VAN DAM, K. 2004. Antecedents and consequences of the employability orientation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 13(1):29-51. [ Links ]

VANDENBERG, R.J. & NELSON, J.B. 1999. Disaggregating the motives underlying turnover intentions: When do intentions predict turnover behavior? Human Relations, 52(10):1313-1336. [ Links ]

VAN DER HEIJDE, C.M. & VAN DER HEIJDEN, B.I.J.M. 2006. A competence-based and multidimensional operationalization and measurement of employability. Human Resource Management, 45(3):449-476. [ Links ]

VAN DER HEIJDEN, B.I.J.M. & BAKKER, A.B. 2011. Toward a mediation model of employability enhancement: A study of employee-supervisor pairs in the building sector. The Career Development Quarterly, 59:232-248. [ Links ]

VAN VIANEN, A.E.M., FEIJ, J.A., KRAUSZ, M. & TARIS, R. 2003. Personality factors and adult attachment affecting job mobility. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 11(4):253-264. [ Links ]

WANG, J. & WANG, X. 2012. Structural equation modeling: Applications using Mplus. West Sussex: Wiley. [ Links ]

WATERMAN, R.H., WATERMAN, J.A. & COLLARD, B.A. 1994. Toward a career resilient workforce. Harvard Business Review, 72(4):87-95. [ Links ]

WELMAN, C. KRUGER, F. & MITCHELL, B. 2005. Research methodology (3nd ed.) Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

WITTEKIND, A., RAEDER, S. & GROTE, G. 2010. A longitudinal study of determinants of perceived employability. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31:566-586. [ Links ]

ZAFIROVSKI, M. 2005. Social exchange theory under scrutiny: A positive critique of its economic-behaviorist formulations. Electronic Journal of Sociology:1-40. [ Links ]

Accepted: August 2014