Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versão On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.17 no.5 Pretoria 2014

ARTICLES

A review of factors affecting the attractiveness of Angola to private equity (PE) investments

Estefania JoverI; Chipo MlamboII

IMcKinsey & Company, Luanda, Angola

IIGraduate School of Business, University of Cape Town

ABSTRACT

Angola's attractiveness to PE investors and the potential to increase PE investments in the country are explored. Primary data were collected using a survey of 18 PE funds that invest or have considered investing in Angola, followed by 10 expert interviews to gain deeper insight into the country's institutional and economic environment, and its potential for PE investments. It is found that most PE funds are attracted to Angola by its rapid economic growth and high potential returns. The country is also vastly undersupplied, and many key economic sectors are fast developing, presenting exciting opportunities for investors. Nevertheless, PE in Angola remains limited, mainly owing to the difficulty of doing business in Angola, and owing particularly to the unfavourable regulatory environment. There is no regulation or process when it comes to the registration of PE funds in Angola, and any new regulation that applies to foreign investments is marred by unnecessary red tape, making it difficult for the investment to enter the market. Only two funds are authorised to operate in Angola: Fundo de Investimento Privado de Angola (FIPA), and BESA Activ. Streamlining regulation is critical to increasing PE flows to Angola in order to advance the country's economic and social objectives.

Key words: private equity, Angola, regulation, investors, emerging markets

1 Introduction

Private equity (PE) is an important source of capital, and has a largely positive impact on private-sector growth (International Finance Corporation (IFC), 2009; 2010; 2011). This applies particularly in the context of emerging markets, where financial markets are still under-developed. Buyout returns in these markets are driven largely by growth and efficiency, rather than by leverage or multiple expansions (IFC, 2010). According to Makhene (2009), measuring the impact of PE on emerging markets is important because of its implications for international development. PE transactions span different geographical areas and influence productivity, employment, corporate governance, management practices, and the broader economy (see, e.g., Cumming, Wright & Siegel, 2007; Wright, Gilligan & Amess, 2009; Wood & Wright, 2009). Nevertheless, PE has received little attention in the financial press and academic literature (Banerjee, 2008; Jenkinson, 2009; Lerner, 2008; Robinson & Sensoy, 2011). This gap in the research on PE is particularly true of emerging markets (Wright, Pruthi & Lockett, 2005; Groh, 2009; Meuleman & Wright, 2011). This therefore limits our understanding of the impact of PE on private-sector development in emerging economies.

At the aggregate level, PE investment in emerging markets has increased almost sevenfold in recent years, rising from US$ 7 to 48 billion between 2004 and 2008 (Emerging Markets Private Equity Association (EMPEA), 2011). However, as a share of the global deal value, it only increased from 3.8 per cent to 13.5 per cent, which is still a very small share (EMPEA, 2011). Moreover, the distribution is skewed towards a few selected markets, with the whole of Sub-Saharan Africa accounting for only 2 per cent (US$635 million) of the total emerging market PE investment in 2010, while Asia took up 64 per cent (EMPEA, 2011). PE activity peaked at an average of US$740 billion in 2007, but slid to an average of US$105 billion in 2009 (EMPEA, 2011).

While the frontier African markets currently receive a small fraction of the total emerging market PE investments, the region registered one of the fastest growth rates among emerging markets in 2010 (EMPEA, 2011). Angola, for example, reported an annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate of over 13.9 per cent between 2005 and 2010, and a sharp decline in inflation from over 100 per cent per annum in 2002, to about 13 per cent since 2006 (International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2011). Angola's enormous progress in economic growth in the nine years, since the end of its 27-year long civil war has been driven largely by the substantial expansion of its crude-oil production and export capacity, bolstered by high international oil prices, and political stability and peace (McKinsey, 2010). Oil prices rose from less than US$20 to more than US$145 a barrel in 2008 (McKinsey, 2010).

The economic growth in Angola notwithstanding, its government is facing increasing pressure to diversify and re-structure the economy away from oil into more labourintensive sectors. The economy is currently heavily dependent on oil revenues, with these accounting for nearly 80 per cent of government revenue, 90 per cent of exports and 47 per cent of the country's GDP (African Development Bank (ADB), 2013). This makes the economy vulnerable to oil price shocks (ADB, 2013). Against this backdrop, PE could provide the capital, expertise and experience that are critical to supporting private-sector-led expansion and growth in the country. This would, in turn, help generate new employment opportunities, facilitate poverty reduction, and support the country's diversification efforts.

Given the importance of PE investments, an array of factors makes a country conducive to these investments. These factors are high GDP growth rates (Bain & Company, 2010; Meerkatt & Liechtenstein, 2010; IFC, 2010); the protection of property and ownership rights (La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Schleifer, Vishny, 2000; Acemoglu & Johnson, 2005; Groh & Liechtenstein, 2011; Meerkatt & Liechtenstein, 2010); good corporate governance (Jensen, 1989; Kaplan, 1989; La Porta et al., 2000; Cumming et al., 2007; Leslie & Oyer, 2009; Groh & Liechtenstein, 2011; Wright et al., 2009; Wood & Wright, 2009); regulation and harmonisation (Mauro, 1995; Lerner, Sorensen & Stromberg, 2009; Cumming & Johan, 2007); transparency (Cumming & Johan, 2007); the absence of barriers to free trade (Lerner et al., 2009); the absence of corruption (Mauro,1995; Lerner et al., 2009); low or favourable taxation (Gompers & Lerner, 1998; Meerkatt & Liechtenstein, 2010); large deal flow (Groh, 2009); access to viable investments (Wright et al., 2005); academic and industrial research and development (R&D) (Gompers & Lerner, 1998); the maturity of the PE market (Groh, 2009); better accounting standards (Cumming, Schmidt & Walz, 2010); and reasonable government intervention (Lerner, 2002; Brander, Du & Hellmann, 2010).

Nothing has been published on these factors in the Angolan context, and this pioneering study accordingly investigates, basing the investigation on a survey and interviews, how the Angolan market ranks on these measures/ indicators. In this way, Angola's attractiveness to PE investors is explored, as is also its potential for increasing PE investments in the country. While the country's market appeal and operational challenges and risks to PE investment are considered, the results, analysis and discussion are founded on a major theme derived from the data, the regulatory environment.

Before detailing the research methodology, the measures/indicators listed above are briefly reviewed.

2 Literature review - factors promoting PE investments

Superior GDP growth is a key trend attracting PE investors to emerging markets (Meerkatt & Liechtenstein, 2010). Superior and sustained GDP growth permits PE firms to invest primarily in companies linked to domestic rather than export markets (IFC, 2010).

Property rights institutions,1 in particular the protection of shareholders and creditors by the legal system, positively influence long-run economic growth, investment and financial development (Acemoglu & Johnson, 2005). With a strong legal system, PE firms can contract at a distance, knowing that their contracts will be enforced (Meerkatt & Liechtenstein, 2010), and that banks can confidently provide debt capital.

Regulation and harmonisation affect investment volume and portfolio allocations, particularly when transparency is lacking (Cumming & Johan, 2007). Barriers to free trade, greater complexity in establishing new entities, and increased corruption are associated with fewer leveraged buyouts (Lerner et al., 2009; Mauro, 1995). A weaker regulatory environment increases the costs associated with managing funds in emerging countries, and makes it difficult to apply due diligence.

Taxation also affects the attractiveness of countries for PE investments (Meerkatt & Liechtenstein, 2010). For example, in their study of the United States over a period of 25 years, Gompers and Lerner (1998) show that the capital gains tax influences PE activity -with lower tax rates leading to a greater quantity of capital raised.

According to Groh (2009), particular regions become attractive to investors only if the deal flow is large enough, and the transaction volumes and expected payoffs justify the increased management costs. Although access to debt finance is often regarded as a driver of PE activity, in emerging markets where financial markets are still under-developed, the emphasis appears to be on growth (Banerjee, 2008; IFC, 2010) and the development of equity markets (Lerner et al., 2009) rather than on the provision of debt or financial gearing.

Access to viable investments is another important determinant of the attractiveness of a regional market to PE investments. Meuleman and Wright (2011) find that in emerging markets PE firms are more likely to rely on local partners through cross-border syndication to gain knowledge about the institutional environment. The viable investments are identified by using valuation models that are relatively homogeneous across countries and are driven to a large extent by fund type and focus (Smolarski, Wilner & Yang, 2011). According to Fraser-Sampson (2010), four factors, namely earnings, multiples, leverage and timing, should work together to create value for the investor.

Gompers and Lerner (1998) find that academic and industrial (R&D) expenditure is significantly related to venture capital activity. In addition, the maturity of the PE market, as reflected in the number of players and supporting institutions, may attract investors (Groh, 2009). As PE funds deliver a good performance and build a reputation, they are likely to raise follow-on funds with greater ease. This is because returns from these funds are persistent, and exceed those of first-time funds (Kaplan & Schoar, 2005).

Informational asymmetries can lead to market failure, in that some potentially valuable transactions might fail to take place, resulting in a shortage of entrepreneurial finance (Cumming et al., 2010). Although some of these asymmetries can be mitigated with the use of better accounting standards, leading to faster deal origination (Cumming et al., 2010), there is a rationale for government intervention to fill the void. Governments may be helpful in providing certain kinds of support, such as financial support, but may become less useful when they have actual control over business decisions (Brander et al., 2010).

3 Research methodology

Both qualitative and quantitative data-collection methods and analyses were used to provide a richer contextual basis for interpreting the results (Kaplan & Duchon, 1988). Secondary data were obtained from a number of sources, including country and government reports, relevant Angolan laws, sector studies, local media articles, published statistics, macroeconomic data and forecasts, accounting statements of Angolan companies, peer-reviewed journal articles, and the internet. Last, but not least, a review of the Angolan regulatory environment was important for the findings to be put into context.

Primary data were collected in October 2011, using a survey questionnaire and interviews. In the questionnaire design phase, exploratory interviews were conducted with two industry experts2 in order to confirm the measures/indicators used, and to gain new insights into the questionnaire design. Before launching the survey, a pilot test was conducted to ensure that the questions were clear and practical. The questionnaire was then administered online to local and international PE investors with a local presence or interest in Angola. Although the responses were treated with anonymity, a list of potential respondents was compiled prior to completing the questionnaire and an identifier was assigned to each respondent to ensure that only the target audience participated in the survey and for tracking purposes during the data collection phase.

Some 78 PE firms were invited to participate, 34 of which were identified in consultation with experts and our own knowledge of the Angolan market. The remaining 44 are registered members of the South African Venture Capital & Private Equity Association (SAVCA).

The questionnaire was organised in three sections:

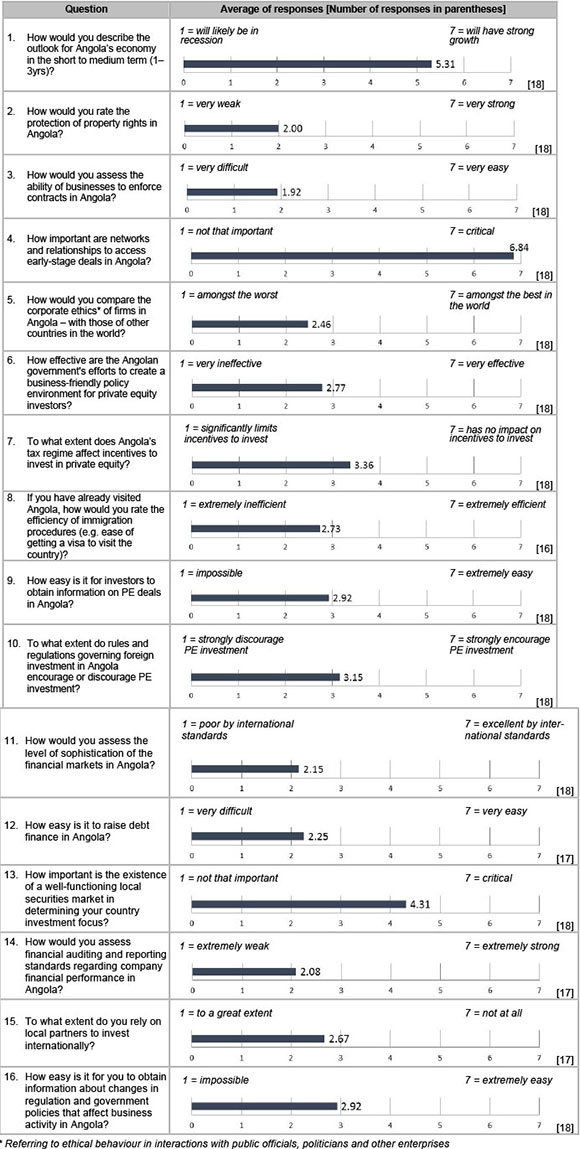

1) First, in order to gauge the temperament of the Angolan investment climate, respondents were asked 16 specific questions, to which they were required to respond on a 7-point Likert scale (see Appendix 1). These questions related broadly to all the measures/indicators listed and discussed in the literature review section.

2) Secondly, respondents were asked to indicate what they considered to be the five most attractive features of the Angolan market, from the most attractive (given a score of 5) - to the least attractive (given a score of 1).

3) Lastly, respondents were asked to select the five major deterrents to PE investment in Angola, from the most problematic (given a score of 5) to the least problematic (given a score of 1).

The objective of the latter two sections was to understand the main drivers and barriers to PE investments in Angola, as experienced by the PE funds, and to build on the data sourced from the first section of the questionnaire.

The last stage of the research process consisted of 10 expert, semi-structured face-to-face interviews with relevant public-sector officials and private-sector agents in Angola. The informant interviewees included local PE funds, financial service providers with an Angolan presence, Angolan legal experts, development finance institutions and government officials, particularly policy-makers. This diverse profile of target interviewees helped ensure that different perspectives and points of view were captured. Questions were mostly open-ended, allowing the interviewees to explain and build on their responses, and were customised according to the experience and expertise of the interviewee and the objective of the meeting.

In accordance with Angolan government protocol, meeting-request letters with public-sector officials were hand-delivered to the appropriate ministry or agency. These letters were written in Portuguese, the official language of Angola. A follow-up phone call to the appropriate secretarial/administration department was made where necessary. Each interview was tape-recorded and subsequently transcribed. The research demanded a thorough understanding and exploration of the data, in order to enable its coding according to predefined themes, such as taxation and barriers, as discussed in the literature review section of the study. In line with similar studies (e.g. Groh, 2009; Van Deventer & Mlambo, 2009), the categorisation and rearrangement of the data formed a key component of the data-analysis process (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2009). Figure 1 gives an overview of the methodological process of the study.

4 Results, analysis and discussion

Eighteen of the 78 PE firms to whom the survey was sent responded, of whom eight were SAVCA members. The response rate of 23 per cent was low, but it was deemed acceptable considering the size and maturity of the Angolan PE market. Of the 18 respondents, 16 were investing only in emerging markets, while the remaining two were seeking opportunities in both developed and emerging markets. In terms of regional focus, 14 invested solely in Africa, two operated in Latin America and Africa, and the remaining two were focusing generally on emerging markets, irrespective of the region. Only seven respondents reported having direct exposure to the Angolan market, three reported having indirect exposure, and the remaining eight currently had no exposure.

4.1 Angola's market appeal

The respondents viewed Angola as an attract-tive destination for PE investments because of the country's high growth (receiving 20.2 per cent of scores), access to viable investments (receiving 15.6 per cent of scores), the competitive advantage of local companies (13.6 per cent of scores), and the availability of natural resources (12.8 per cent of scores), as shown in Figure 2. When it came to Angola's outlook on going forward, the respondents were of the opinion that Angola was likely to grow strongly in the short to medium term. This is indicated by an average score of 5.31 out of a possible 7, on the Likert scale question pertaining to outlook in Appendix 1. The responses varied by between one and two standard deviations from the mean.

From the interviews, it was generally reported that many sectors of the Angolan economy are still undersupplied. In fact, this presents a unique investment opportunity, especially given that opportunities in developed markets are currently constrained (Banerjee, 2008). In addition, the lack of competitive pressures in Angola enables companies to charge higher premiums and thus increase investor returns. However, in line with Allen and Song (2002) and Granovetter (2005), the survey respondents overwhelmingly believed that networks and relationships are crucial to accessing deals in Angola. This is indicated by an average score of 6.84 out of a possible 7 on the Likert scale for Question 4 in Appendix 1.

With the new liquefied natural gas (LNG) facility being the single largest investment ever made in Angola (US$9 billion), the oil and gas sector is still the most developed sector in the Angolan economy. However, investors are looking to other, less saturated and undersupplied sectors like agriculture for untapped opportunities (interview). Once a major exporter of products, like coffee and cotton, and selfsufficient in most foods, Angola today is a net importer of consumable goods. This is in addition to having the sixteenth-largest agricultural potential in the world, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (African Development Bank, 2011), with fertile soils, a favourable climate, and rich water resources.

Opportunities also exist in the mining sector, which is currently dominated by diamond and petroleum production, as well as an abundance of other minerals like gold, barite, iron, copper, cobalt, granite and marble. With improvements in rail and road networks and the improved investor protection under the newly-approved Mining Law No 31/11 of September 23, 2011,3, 4 mining opportunities are opening up, and investor interest in the sector is reawakening. For example, the Angolan PE fund, Fundo de Investimento Privado de Angola (FIPA) is expected to invest in the expansion and growth of the newly-established mining companies (interview).

Other sectors of interest include breweries, cement, industry and telecommunications. However, some interviewees expressed concern that certain sectors were, in practice, closed to foreign investment, and that there was a lack of transparency in the granting of licences and permits, despite the importance of transparency in PE deals (Cumming & Johan, 2007). On the other hand, the local banking sector has seen phenomenal growth within the past decade (Banco de Fomento Angolano (BFA), 2011). A law was passed that requires international oil companies to channel their payments through the domestic banking system, which was previously deemed incapable of handling these transactions. This new vote of confidence in local banks is expected to result in a capital boost to the local banking sector of around US$10 billion (Reuters, 2011).

Many interviewees also expressed a keen interest in the new public-private partnership (PPP) framework under development. The surge of modern distribution centres like Shoprite, and the growing presence of large industrial groups (e.g. Coca Cola, Nestli and SAB Miller), is adding to Angola's attractiveness as far as investment opportunities are concerned.

4.2 Operational challenges and risks to PE investment

The respondents reported poor accounting and reporting standards, followed by weak investor protection, as being the most important deterrents to PE investment in Angola (see Figure 3). The two factors have been cited in the literature as being important in PE allocation decisions (Groh & Liechtenstein, 2011; La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Schleifer & Vishny, 1998). Thus, improving accounting standards could help build the much-needed investor trust, by mitigating information asymmetries (Cumming et al., 2010) - particularly given that Angola is characterised by high corruption and a lack of transparency. Angola is ranked at the bottom of the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index (168 out of 178 countries).

Corruption and the use of clientele make it difficult to attract foreign equity capital (Lerner et al., 2009; Mauro, 1995). However, contacts are paramount in identifying PE investment opportunities and moving projects forward in Angola, as this interviewee points out:

They [PE funds/financial institutions] will look at the shareholding structure of the project and they will ask me: what is this person bringing to the table? Is it expertise? No. Is he providing finance? No. They are right to ask these questions; but if I do not have this person, I will not get the licence that I need to do the project in the first place.

In this regard, foreign companies are often encouraged to partner with Angolan companies, many of which turn out to be front organisations for government officials (Global Advice Network, 2011). While bad opportunities can be 'served on a golden plate' in Angola, the interesting opportunities are not easily accessible while acting ethically (interview). This makes it particularly hard to engage PE capital, because PE funds have to do everything by the book (interview).

Contrary to the opinions of Groh (2009) and Leeds and Sunderland (2003) respectively, small deal volumes and the absence of a market for public securities were not considered key factors that were discouraging PE investors from increasing their allocations to Angola (see Figure 3). Given that small-deal volumes are associated with high transaction costs, investors presumably expect to earn sufficiently high returns to compensate for these transaction costs. The low importance attached to a market for public securities (Figure 3) could suggest that PE investors are confident that they can exit their investments by other means. Arguably, given the poor accounting and contract enforcement standards, a public securities market may not be useful.

Despite the importance attached to taxation in PE deals (Gompers & Lerner, 1998; Meerkatt & Liechtenstein, 2010), the survey respondents did not rank taxation as a key deterrent to investing in Angola. However, some interviewees indicated that the tax rate was too high to make PE investments feasible, particularly given the returns that foreign investors would demand, in order to take on the investment risk. According to one interviewee:

Why does a foreign investor want to take on Angolan risk? 40 per cent return? This is after tax. The tax rate is 35 per cent. And then you have your admin fees on top of that. So you are looking for an 80 per cent return project. Have you found that project? If so, let me know, because I am still looking.

However, the Director of a major pan-African Investment Bank provided an argument counter to this view. In his experience, investors demand closer to a 30 per cent return if they are to invest in Angola, not 40 per cent. He also observed that the Angolan corporate tax is not dissimilar to that found in other countries, and hence is not a particular disadvantage in the Angolan PE market.5 Moreover, the Angolan government offers tax exemptions and fiscal incentives that can decrease the tax bill and hence improve the profitability of companies and the feasibility of investments. However, the approval process to obtain these exemptions and incentives in Angola is mired in red tape. In this regard, a review of the Angolan regulatory environment will be insightful.

4.3 The Angolan regulatory environment

The Government of Angola (GOA) has a number of pieces of legislation pertaining to private investments and the regulation of financial markets in the country (GOA, 2003a; 2003b; 2005a; 2005b; and 2011). One important piece of Angolan legislation is the Financial Institutions Law No 13/05 of September 30, 2005, which establishes the basic principles for regulating the Angolan financial market. This law distinguishes banking from non-banking institutions, and assigns regulatory authority to appropriate government bodies (see Figure 4).

A second piece of legislation is the Securities Law No. 12/05 of September 23, 2005, which regulates the trading of all securities in Angola. This law is under the control and supervision of the Capital Market Commission, the Comissdo do Mercaco de Capitals (CMC), an autonomous entity within the Ministry of Finance. The CMC regulates, approves and supervises all PE activities in Angola. In December 2011, two funds were authorised by the CMC to operate in Angola: FIPA and BESA Activ. The latter is a real-estate fund, managed by Banco Espiritu Santo Angola (BESA), a subsidiary of Banco Espiritu Santo (BES), a Portuguese bank.

The first of the two funds, FIPA, is a Lxembourg-registered fund and so far is the only PE fund exclusively dedicated to investing in Angola. In July 2011, it reported commitments of US$39 million (short of the fund's initial target of US$100 million). It is an initiative of Banco Angolano de Investimentos (BAI), an Angolan bank partly owned by Sonangol and Norfund. Other subscribers include the European Investment Bank, the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation, and the Danish State Investment Fund. FIPA is managed by Angolan Capital Partners, an Angola-registered company (Giletti, 2011) based in Luanda. However, because of its foreign registration, FIPA is subject to the regulation that applies to foreign entities/investments under Angolan law.

Foreign investments in Angola are regulated and approved by the Angolan Agency for Private Investment (ANIP), which was created in 2003 to support private-sector development. ANIP is responsible for implementing and enforcing the new Private Investment Law No 19/11 of May 2011, which regulates and sets out the procedures for the approval of private investments. Whereas the old law set the minimum investment at US$50,000 for nationals and US$100,000 for foreigners,6 the new law sets the minimum investment at US$1 million. This means that ANIP can process only investments at or above this threshold, and smaller investments will have to be processed through other channels. However, by investing through alternative channels, an investor will forego the attractive fiscal and tax incentives granted by ANIP, and will have difficulty in repatriating profits out of Angola.

Even where the PE transaction meets the US$1 million minimum requirement for approval by ANIP, any subsequent PE investment into the investee company requires a new ANIP approval and any changes in the investee's shareholding structure require ANIP approval. By December 2011, no investment had been approved under the new law and process. In the best-case scenario, it would take about 145 days to process an investment application through ANIP (Figure 5). This excludes the time spent gathering the information and documents requested (which include a technical, economic and financial feasibility study), and the time required to obtain a commercial licence, which is applicable to businesses intending to perform commercial activities.

4.3.1 Challenges with the regulatory environment

There was consensus among the interviewees that the ANIP approval process is burdensome, expensive and time-consuming. It significantly increases transaction costs for would-be investors. According to the law firms consulted, the fact that ANIP shut down for a few months in 2011 to discuss the new law led to serious delays in many investment projects. Numerous applications submitted before this closure had to be re-submitted under the new law and process. This completely disregarded the impact of the cost on investors. Many interviewees stated that ANIP did not have the technical capability in-house to adequately evaluate the required feasibility and environ-mental studies.

In theory, a locally-registered fund would not require ANIP approval. Therefore, local PE funds should therefore greatly simplify and accelerate the PE deal-making process, and would eliminate the US$1 million minimum required for ANIP approval. However, for foreign investors to repatriate profits, ANIP approval and the US$1 million cannot be avoided. Nevertheless, only a once-off approval at registration would be required, and would not have to be repeated each time the fund intends to complete a transaction. BESA Activ (the second fund registered with the CMC) benefits from a preferential arrangement with the Central Bank, Banco Nacional de Angola (BNA), which allows it to transfer capital in and out of the country without ANIP's approval (interview). Unfortunately, information on the requirements and eligibility criteria for such an arrangement could not be accessed.

5 Conclusion

The study explores the factors that attract and/or deter PE investments in Angola. It was found that most PE funds are attracted to Angola first and foremost by its high economic growth and high potential returns. Other attractions, in order of importance, include access to viable investments, the competitive advantage of local companies, the availability of natural resources, the quality of management teams, government support programmes, access to networks and the size of the domestic market. The country is also vastly undersupplied, and many key economic sectors are fast developing, which presents an array of exciting opportunities for investors. However, networks and relationships are very important in accessing early-stage deals in Angola.

A number of deterrents to PE investment in Angola were also cited. These are, in order of importance, poor or extremely weak accounting and reporting standards, weak investor and property rights protection, difficulty for businesses in enforcing contracts, red tape, political risk, the absence of reliable or experienced partners, corruption and the worst-in-the-world corporate ethics, the low quality of business plans, difficulty in obtaining information on deal flows, difficulty in accessing debt finance, few supporting institutions such as banks and accounting firms, an unfavourable tax environment, poor and almost non-existent public securities markets, and small deal volumes. Respondents also felt that the current Angolan regulatory environment discourages PE investment and the government's effort to create a business-friendly policy environment is rather ineffective. Even simple things such as immigration procedures were reported to be extremely inefficient.

As can be observed from the above discussion, the deterrents outweigh the attract-tions. Thus PE in Angola remains limited, owing not necessarily to the lack of investor interest, but to the difficulty of doing business in the country, particularly in relation to the unfavourable regulatory environment. Thus streamlining regulation is seen as critical to increasing PE flows to Angola, and to advancing Angola's economic and social objectives.

A comparative study of the regulation in Angola with that of other countries could provide valuable information on how regulation could be designed to promote PE investment more effectively. This represents an important area for future research. Current regulation pertinent to PE investment could, for example, be analysed and compared with similar regulation currently in place in South Africa, which is the main destination for PE flows in Sub-Saharan Africa. The lessons learned from a broader study would be invaluable to other African countries where PE investors are currently deterred by regulatory weaknesses.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the financial support provided by the National Research Foundation (NRF) in developing this manuscript for publication. Any opinion, findings, conclusions and/or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and not of the NRF. We also thank Dr David Barraclough for editing the manuscript to improve its readability. Without his assistance publication would not have been possible.

References

ACEMOGLU, D. & JOHNSON, S. 2005. Unbundling institutions. Journal of Political Economy, 113(5): 949-995. [ Links ]

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK. 2011. Angola 2011-2015 Country Strategy Paper and 2010 Country Portfolio Performance Review. Tunisia. Available at: http://www.afdb.org/en/documents/document/angola-2011-2015-country-strategy-paper-2010-country-portfolio-performance-review-23223/ [accessed 2011-1007]. [ Links ]

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK. 2013. Angola economic outlook. Available at: http://www.afdb.org/en/countries/southern-africa/angola/angola-economic-outlook [accessed 2013-12-13]. [ Links ]

ALLEN, F. & SONG, W. 2002. Venture capital and corporate governance. Philadelphia: Wharton School. Available at: http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/papers/1115.pdf [accessed 2011-10-07]. [ Links ]

BAIN & COMPANY. (2010). Global private equity report. Available at: http://www.bain.com/Images/Global_PE_Report_2010_PR.pdf [accessed 2011-10-07]. [ Links ]

BANERJEE, A. 2008. Private equity in developing nations. Journal of Asset Management, 9(2):158-170. [ Links ]

BFA. 2011. A presentation at Angola: Africa 's Emerging Capital Market Giant Conference, London, 8 November 2011. [ Links ]

BRANDER, J., DU, Q. & HELLMANN, T. 2010. Governments as venture capitalists: Striking the right balance. In: J. Lerner (ed.) Globalization of alternative investments: The global economic impact ofprivate equity report. Working papers, 3, 25=37, Geneva: World Economic Forum. Available at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_IV_PrivateEquity_Report_2010.pdf [accessed 2011-10-07]. [ Links ]

CUMMING, D. & JOHAN, S. 2007. Regulatory harmonization and the development of private equity markets. Journal of Banking and Finance, 31:3218-3250. [ Links ]

CUMMING, D., SCHMIDT, D. & WALZ, U. 2010. Legality and venture capital governance around the world. Journal of Business Venturing, 25: 54-72. [ Links ]

CUMMING, D., WRIGHT, M. & SIEGEL, D.S. 2007. Private equity, leveraged buyouts and governance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 13(4):439-460. [ Links ]

EMPEA. 2011. Industry statistics. Available at: http://www.empea.org/research/data-and-statistics/full-year-2011-em-pe-industry-statistics [accessed 2011-10-07] [ Links ]

FRASER-SAMPSON, G. 2010. Private equity as an asset class. West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

GILETTI, T. 2011. Fundo de Investimento Privado (FIPA). Promotion and development of Angola's financial system. Venture capital and private equity in Angola. Presentation given at: 'Angola: Africa 's Emerging Capital Markets Giant' conference, 8 November 2011, London. [ Links ]

GLOBAL ADVICE NETWORK. 2011. Business anti-corruption portal. Available at: http://www.business-anti-corruption.com/ [accessed 2011-10-07]. [ Links ]

GOMPERS, P. & LERNER, J. 1998. What drives venture fundraising? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Microeconomics (July 1998):149-192. [ Links ]

GOVERNMENT OF ANGOLA. 2003a. Angolan Private Investment Promotion Law, No. 14/03, July 18, 2003. [ Links ]

GOVERNMENT OF ANGOLA. 2003b. Fiscal and Custom Incentives for Private Investment Law, No. 17/03, July 25, 2003. [ Links ]

GOVERNMENT OF ANGOLA. 2005a. Financial Institutions Law, No. 13/05, September 30, 2005. [ Links ]

GOVERNMENT OF ANGOLA. 2005b. Securities Law, No. 12/05, September 23, 2005. [ Links ]

GOVERNMENT OF ANGOLA. 2011. New Private Investment Law, No. 19/11, May 20, 2011. [ Links ]

GRANOVETTER, M. 2005. The impact of social structure on economic outcomes. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(1):33-50. [ Links ]

GROH, A. & LIECHTENSTEIN, H. 2011. International allocation determinants of institutional investments in venture capital and private equity limited partnerships, International Journal of Banking, Accounting and Finance, 3(2-3):176-206 [ Links ]

GROH, A.P. 2009. Private equity in emerging markets. IESE Business School Working Paper, No 779, Navarra. Available at: http://www.iese.edu/research/pdfs/di-0779-e.pdf [accessed 2011-10-07]. [ Links ]

IFC. 2009. The case for emerging market private equity. Available at: http://newgrowthfund.com/article_IFC.pdf [accessed 2011-10-07]. [ Links ]

IFC. 2010. IFC's experience in emerging markets private equity. Emerging Markets Private Equity Association, 6(1):6-9. [ Links ]

IFC. 2011. The case for emerging market private equity. Available at: http://www1.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/0b26b7004bc30d86a2b5e71be6561834 /EM_PE_Sharing_IFCs_Experience_v9_February2011.pdf?MOD=AJPERES [accessed 2011-10-07]. [ Links ]

IMF. 2011. Data and statistics: World economic outlook database. Available at: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/01/weodata/index.aspx [accessed 2011-10-07]. [ Links ]

JENKINSON, T. 2009. Private equity. Said Business School, Oxford University and CEPR. [ Links ]

JENSEN, M. 1989. The eclipse of the public corporation. Harvard Business Review (September-October), 61-74. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.201.9573&rep=rep1&type=pdf [accessed 2011-10-07] [ Links ]

KAPLAN, B. & DUCHON, D. 1988. Combining qualitative and quantitative methods. In: Information systems research: A case study, Management Information Systems Quarterly, 12(4):571-587. [ Links ]

KAPLAN, S. N. 1989. The effects of management buyouts on operating performance and value. Journal of Financial Economics, 24:217-254. [ Links ]

KAPLAN, S.N. & SCHOAR, A. 2005. Private equity returns: Persistence of capital flows. Journal of Finance, 60:1791-1823. [ Links ]

LA PORTA, R., LOPEZ-DE-SILANES, F., SCHLEIFER, A. & VISHNY, R. 2000. Investor protection and corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics, 58:3-27. [ Links ]

LA PORTA, R., LOPEZ-DE-SILANES, F., SCHLEIFER, A. & VISHNY, R. 1998. Law and finance.Journal of Political Economy, 106:1113-1155. [ Links ]

LEEDS, R. & SUNDERLAND, J. 2003. Private equity investing in emerging markets. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 15(4):8-16. [ Links ]

LERNER, J. 2002. When bureaucrats meet entrepreneurs: The design of effective 'public venture capital' programmes. The Economic Journal, 112:F73-F74. [ Links ]

LERNER, J. 2008. Globalization of alternative investments: The global impact of private equity report, Working papers 1, World Economic Forum. Available at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_IV_PrivateEquity_Report_2008.pdf [accessed 2011-10-07]. [ Links ]

LERNER, J., SORENSEN, M. & STROMBERG, P. 2009. What drives private equity activity and success globally? In: J. Lerner (ed.) The globalization of alternative investments. The global economic impact of private equity report, Working papers, 2:63-76, World Economic Forum. [ Links ]

LESLIE, P. & OYER, P. 2009. Managerial incentives and value creation: Evidence from private equity. Stanford University. Available at: http://www.stanford.edu/~pleslie/private%20equity.pdf [accessed 2011-10-07]. [ Links ]

MAKHENE, M. 2009. Alternative growth: The impact of emerging market private equity on economic development. Neumann Business Review, Spring: 17-47. [ Links ]

MAURO, P. 1995. Corruption and growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110:681-712. [ Links ]

MCKINSEY. 2010. Lions on the move: The progress and potential of African economies. The McKinsey Global Institute. Available at: http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/africa/lions_on_the_move. [ Links ] [accessed 2011-10-07].

MEERKATT, H. & LIECHTENSTEIN, H. 2010. New markets, new rules: Will emerging markets reshape private equity? Boston Consulting Group and IESE Business School. Available at: http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/9c197b8049bdb99b960cd6a8c6a8312a/BCG%2B New%2BMarkets%2BNew%2BRules%2BNov%2B10.pdf?MOD=AJPERES [accessed 2011-10-07]. [ Links ]

MEULEMAN, M. & WRIGHT, M. 2011. Cross-border private equity syndication: Institutional context learning. Journal of Business Venturing, 26:35-48. [ Links ]

NORTH, D. 1990. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

REUTERS. 2011. Angola passes law to force oil firms to use local banks. Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/11/10/angola-banks-idUSL5E7MA2FF20111110 [accessed 2011-10-07]. [ Links ]

ROBINSON, D.T. & SENSOY, B.A. 2011. Private equity in the 21st century: Liquidity, cash flows and performance 1984-2010, Fisher College of Business, Working Paper Series. Available at: https://fisher.osu.edu/blogs/efa2011/files/FIE_2_1.pdf [accessed 2011-10-07]. [ Links ]

SAUNDERS, M., LEWIS, P. & THORNHILL, A. 2009. Research methods for business students, (5th ed.) Essex: FT Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

SMOLARSKI, J., WILNER, N. & YANG, W. 2011. The use of financial information by private equity funds in evaluating new investments. Review of Accounting and Finance, 10(1):46-68. [ Links ]

VAN DEVENTER, B. & MLAMBO, C. 2009. Factors influencing venture capitalists' project financing decisions in South Africa. South African Journal of Business Management, 40(1):33-41. [ Links ]

WOOD, G. & WRIGHT, M. 2009. Private equity: A review and synthesis. International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(4):361-380. [ Links ]

WORLD BANK. 2012. Doing business report. The World Bank. Available at: http://www.doingbusiness.org/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2012 [accessed 2013-12-13]. [ Links ]

WRIGHT, M., GILLIGAN, J. & AMESS, K. 2009. The economic impact of private equity: What we know and what we would like to know. Venture Capital, 11:1-21. [ Links ]

WRIGHT, M., PRUTHI, S. & LOCKETT, A. 2005. International venture capital research: From crosscountry comparisons to crossing borders. International Journal of Management Review, 7(3):135-165. [ Links ]

Accepted: May 2014

Endnotes

1 Institutions are broadly defined as the "rules of the game" that structure the political, economic and social interactions supporting the effective functioning of market economies, by ensuring that economic transactions do not incur undue costs or risks (North, 1990).

2 One is a reputable individual with a significant number of years of experience in the industry and the other is an academic active in research on the topic.

3 The new mining law came into effect on 23 December, 2011. Under the new law: 1) the holders of mining titles are entitled to the commercial right of the product of exploration (Article 188); 2) state involvement is still demanded, but set at a minimum of 10% (Article 11).

4 The Mining Law 1/92 of January 17 1992, failed to provide such protection. The diamond sector was regulated by Diamond Law No. 16/94 of October 17, 1994.

5 The corporate tax rate in Angola was recently lowered from 35% to 30%.

6 In practice, a US$ 200 million threshold was often applied to foreign investment.

Appendix 1

Perceptions about the Angolan investment climate

[A summary of survey results emphasising key areas of concern for investors. Each bar represents the average response on the Likert scale, with the numbers of valid responses per question given in parentheses]