Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versão On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.17 no.5 Pretoria 2014

ARTICLES

Ethical business practices in the Eastern Cape automotive industry

Hendrik R LloydI; Michelle R MeyII; Koman RamalingumII

ISchool of Economics, Development Studies & Tourism, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

IISchool of Industrial Psychology and Human Resource Management, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

ABSTRACT

High profile scandals have brought about a renewed interest in business ethics and, in particular, in understanding the factors that promote ethical behaviour. Business ethics is about identifying and implementing values, rules and standards of conduct for guiding morally right behaviour in an organisation's interaction with its stakeholders. Against this background a quantitative analysis of the ethical practices of 46 companies operating in the Eastern Cape automotive industry was conducted to determine the extent to which ethics-related interventions contributed to establishing and maintaining an ethical organisational environment. A structured online questionnaire was used to collect the data. The data collected was subjected to extensive statistical analyses, including Cronbach Alpha coefficients and item total correlations, and various descriptive statistics were included as a quantitative summary of the data. A constant reference value for the study was also calculated to allow inferences regarding the significance of the tested variables to the study. The results revealed that the organisations in the sample are highly ethical due to the presence of ethics-related interventions, including a code of ethics, committed leadership, adherence to internal and external governance requirements, compliance with legislation and encouragement and disclosure of unethical behaviour. In light of the high number of ethical scandals internationally, this study will add to the empirical body of business ethics research, as it provides organisations with a framework to establish and maintain an ethical business environment.

Key words: business ethics; automotive industry; South Africa; Eastern Cape Province

1 Introduction

Corporate indiscretion, wrongdoing and corruption are frequently the subject of international media attention. Well-known companies such as Enron and Tyco in the United States and Parmalat and Vivendi in Europe have been plagued by corporate scandals resulting in liquidation of corporate assets, the demise of once powerful brands and extensive litigation (Fombrun & Foss, 2004). 'Ethics in South Africa - or rather the lack thereof - has likewise been in the news, from collusion and price fixing findings by the South African Competition Commission to corruption cases in the public sector' (Schoeman, 2012a:65).

Fraud cases reported in South African organisations increased by 67 per cent, from 33 000 to 55 300, during the six year period from 1986 to 1992 (Van Zyl & Lazenby, 1999). More recently, the MTN Group was slapped with a $4.2 billion lawsuit by Turkish cell phone company, Turkcell, around allegations of bribery and corruption (Anon, 2013). Such corporate scandals and financial disasters have threatened not only the position of many senior managers but also the financial survival of the companies over which they preside (Knights & O'Leary, 2005:359). Scandals such as those referred to above have raised the profile of and brought renewed interest to business ethics - specifically the need for a better understanding of the factors that promote ethical behaviour. While conventional wisdom suggests that unethical behaviour is the result of a few 'bad apples', there is mounting evidence that, in addition to personal values, the organisational environment plays a critical role in encouraging ethical conduct (Rossouw & Van Vuuren, 2013; Zona, Minoja & Coda, 2013).

Against this background, a study was conducted to determine the extent to which ethics- related interventions contributed to establishing and maintaining an ethical organisational environment. As such, the study comprised a quantitative analysis of the ethical practices of companies operating in South Africa's Eastern Cape Province automotive industry. A structured online questionnaire, based on the literature reviewed including a study conducted by Mey (2004), was used to collect the data. This paper reports on the ethical practices and interventions identified in the literature and based on the empirical findings from the study. It concludes with recommendations for improving the ethical environment and conduct within organisations, in keeping with international best practice and governance and legislative requirements.

The review of the literature follows.

2 Literature survey

2.1 Defining business ethics

According to Lewis (1985:381) 'business ethics is rules, standards, codes or principles which provide guidelines for morally right behavior and truthfulness in specific situations'. According to Rossouw and Van Vuuren (2010:5) 'Business ethics is about identifying and implementing standards of conduct in and for business that will ensure that the interests of stakeholders are respected. Business ethics is about a conception of what is good (values and standards) that guides the business (self) in its interaction with others (stakeholders)'. Business ethics refers to the ability to differentiate right from wrong and to choose to do what is right in terms of actions and decisions (Zgheib, 2005). The decisions involve taking actions which might benefit or harm various stakeholders, whether they are shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers or the broader society within which the organisation operates (Gandz & Hayes, 1988:657). Business ethics applies to employees, management and the organisation as a whole; therefore it can be personal or institutional in nature (Gruble, 2011; Pattan, 1984). At a macro level, business ethics is concerned with the role of business in society and its moral and legal obligation to abide by the law, while at a corporate level it relates to ethical issues facing individual corporate entities when formulating and implementing strategies, and, at the individual level, it involves the values, behaviour and actions of individuals within organisations (Fieser, n.d.; Josephson, 2012).

When implementing business ethics, companies can adopt either a stockholder/ shareholder-focused or stakeholder-focused approach (Freeman, 2001; Freeman & Reed, 1983). In the case of a shareholder-focused approach, the attention is on the interests of the owners and the emphasis is on generating profit. In the stakeholder-focused approach, companies act and decide with the interests of all stakeholders in mind, including employees, customers, suppliers and the broader community. The ethical expectations that society has of modern corporations has shifted and changed in recent times, and corporations are increasingly being regarded as integral and key players in the wellbeing of society (Rossouw & Van Vuuren, 2013:99). This is especially relevant in the South African context where new corporate codes of conduct legislation such as the King Report on Corporate Governance 2009 place an even greater burden on an organisation's board of directors and senior management to take all stakeholders into account when making ethical decisions (Barnard, 2012:10). Furthermore, there is growing recognition, supported by research, that good ethics can have a positive economic impact on the performance of firms and that 'good ethics is good business' (Joyner & Payne, 2002:297). Companies that commit to ethical behaviour toward their stakeholders or emphasise compliance with their code of conduct perform better financially than those that do not (Chauhan & Chauhan 2002, in Barnard, 2012; Verschoor, 1998). 'Many organi sations acknowledge that the preservation of corporate reputation, respect for ethically discerning consumers and the protection of company assets against fraud and corruption, result in investor confidence and good business' (Van Vuuren, 2002:21). Additionally, being seen to be ethical can have the following advantages for the organisation: improved brand and business awareness and recognition, easier access to capital, lower cost of capital and new sources of finance from ethical investors, enhanced employee commitment and customer loyalty, and the recruitment of top talent for employees and the board (Riley, 2012; Schoeman, 2012b). Thus the benefits of creating an ethical organisation outweigh potential disadvantages such as: higher costs of utilising 'ethical' supply chain partners rather than those that offer the lowest prices and higher overheads incurred in training, communicating and monitoring of ethical policy (Riley, 2012).

2.2 Components of ethical organisations

If the organisational environment is important in promoting ethical conduct or if 'organizations are social actors responsible for the ethical and unethical behaviours oftheir employees' as proposed by Victor and Cullen (1988), then what constitutes an ethical organisation, and how can such an organisation be created? According to Van Vuuren (2002:22), 'an ethical organisation is one that has a strong ethical value orientation, lives those values, and practices them when engaging with all internal and external stakeholders'. Van Vuuren (2002) further proposes a three-levelled strategy for ethics to become truly engrained into an organisation's culture, namely the formulation of an ethics management system at a strategic level, the design of systems for strategy implementation and finally the application of ethical principles in the daily activities of every employee. In addition, Mayer (2011) proposes three key components of the ethical environment that work together to promote ethical behaviour: ethical leadership, ethical practices and an ethical climate. Ethical leaders set the tone for how employees behave in organisations by conducting themselves in a moral manner, and by taking decisions that are fair and in the best interest of their employees and other stakeholders, a view shared by Granger (2011), and Robbins and Judge (2009). Leaders are also expected to discipline employees who violate ethical standards. Ethical practices are actions or activities related to ethics that are repeated and recognisable in organisations; they refer to what organisations actually do. According to Mayer (2011), research demonstrates that there are six critical organisational practices relating to ethics: 'recruitment and selection', 'orientation and training', 'policies and codes', 'reward and punishment systems', 'accountability and responsibility' and 'decision-making.' An ethical climate is created when there exists a general perception among employees that the organisation is ethical. Creating an organisational context that promotes ethical conduct is reliant on having policies and procedures in place with regard to acceptable behaviour and standards. In addition, Robbins & Judge (2009) include the importance of communicating ethical expectations, over and above having the necessary policies and codes. Furthermore, a key finding of the 2005 National Business Ethics Survey, conducted by the Ethics Resource Centre, was that an ethics communication strategy was not enough to create desired outcomes and that employees needed to see their superiors and peers demonstrate ethical behaviour in the work they do and the decisions they take (Seligson & Choi, 2006:2). Of importance, also, is for organisations to make ethics a conscious management focus, and to monitor and manage it. Measurement of ethics through regular ethics audits will assist an organisation to identify and timeously address ethical 'hot spots'.

Therefore, and in accordance with the aforementioned components of ethical organisations, several key elements have been identified as being necessary for an ethical environment to prevail, as outlined below.

2.2.1 Elements of an ethical environment

Creating an ethical organisation starts with top management's commitment to ethics (Lloyd & Mey, 2010; Van Vuuren, 2002). 'Starting with the CEO, senior managers must continually demonstrate the company's core values and reinforce standards of behaviour' (Archer, 2008:32). Top management commitment should be followed by the appointment of an ethics manager or officer to create and maintain an ethical organisational culture and to effectively manage corporate ethics (Van Vuuren, 2002). One of the main responsibilities of an ethics manager is to ensure that the organisation has a strong code of ethics that applies to all employees, has been prepared by both managers and employees (Archer, 2008) and includes issues that relate to all the organisation's stakeholders. The ethics manager would be responsible, also, for co-ordinating the orientation and training on ethical standards, as well as for driving the communication efforts of the organisation with respect to reinforcing the company's standards of behaviour. In addition, the Ethics Resource Centre (ERC) has adopted the following key elements, based on the Federal Sentencing Guidelines for Organisations, as being necessary for an ethical environment to prevail (ERC, 2012): a specific office, telephone line, email address or website for advice about workplace ethics issues; a means for an employee to report confidentially or anonymously violations of ethics standards; evaluation of ethical conduct as part of regular performance appraisals and discipline for employees who violate ethics standards, a view supported by Archer (2008:36): 'establishing standards of behaviour without being prepared to discipline will not promote compliance'. Furthermore, Lloyd & Mey (2010) argue that an ethics focused reward system is critical to institutionalising ethical behaviour.

Corporate ethics and standards of conduct are matters of governance; however, having an ethical organisational environment not only depends on internally developed policies and interventions, but is also determined by the external governance requirements and the legislative context. This is discussed in the following section.

2.3 External governance mechanisms

Creating and maintaining a positive ethical environment has been recognised as an important aspect of corporate governance (Elango, Paul, Kundu & Paudel, 2010). Corporate governance refers to the framework of rules and practices by which a board of directors ensures accountability, fairness and transparency in an organisation's relationship with all its stakeholders (shareholders, customers, management, employees, government and the community) (BusinessDictionary.com, n.d.).

2.3.1 King Reports I, II and III

In South Africa, the corporate governance landscape has been transformed and shaped largely by the King Reports. King I, issued in 1994, incorporated a code of corporate practice and conduct that went beyond the corporation and its financial matters, taking into account the organisation's impact on the larger community (Institute of Directors Southern Africa, 2009).

In 2002, King II proposed that organisational strategy development necessitates a sound understanding of social and environmental responsibility, sustainability, stakeholder engagement and the Triple Bottom Line, as well as identifying seven principles of good corporate governance, including transparency, accountability, fairness and social responsibility. King II further recommends that every organisation should report at least annually on the nature and extent of its social, trans-formation, ethical (development of a Code of Ethics), safety, health and environmental management policies and practices, while stakeholder reporting is also important (Institute of Directors Southern Africa, 2009).

The third King report, launched in response to the Companies Act No. 71 of 2008, recognises ethics as a central feature of corporate governance and calls for ethical leadership and effective management of companies' ethics. The King III report specifically recommends assessment, monitoring, reporting and disclosure of an organisation's ethical performance (Institute of Directors Southern Africa, 2009).

Effective and ethical corporate governance, as outlined in the King reports, is significant for reducing costs caused by unethical conduct and essential for the long-term sustainability and success of businesses operating in South Africa.

2.4 Legislative environment

2.4.1 Social and ethics committee

Against the backdrop of the King reports, Section 72 (4) of the Companies Act No.71 of 2008 makes provision for a social and ethics committee. Every state-owned company, listed public company and any other company that scored 500 public interest points in any two of the previous five years (based on the number of employees, annual turnover and third party liability) must have established a social and ethics committee by 1 May 2012. The commit-tee is appointed by the board and is required to report to the board on areas of 'social and economic development', 'good corporate citizen- ship', 'impact of companies activities and products or services on communities', 'consumer relationships' and 'labour and employment' (Companies Act 71 of 2008).

Managing ethics and reporting on ethics are now legal requirements in terms of the new Companies Act. The choice for companies, however, is whether the social and ethics committee will translate into a ticking-the-box compliance exercise or whether it will result in companies' elevating their social and ethical obligations to a strategic board level.

2.4.2 Protected Disclosures A ct No. 26 of2000

Before turning to the Protected Disclosures Act, it is necessary to briefly outline the concept of whistleblowing as a tool to root out corruption and unethical behaviour in organisations. Whistleblowing refers to the disclosure of illegal, unethical or harmful practices in the workplace to parties inside or outside the organisation who might take action (Bainbridge, 2013; Miethe & Rothschild, 1994). The disclosure of such information is regarded as being in the public interest.

The Protected Disclosures Act No. 26 of 2000 is an initiative by the South African government to create an environment that facilitates the disclosure of information and to protect whistleblowers from harassment and victimisation (Protected Disclosures Act 26 of 2000). The latter is especially important given the country's political and cultural history. Due to the potential risks for individual whistleblowers, it is imperative that organisations create an environment that protects and incentivises disclosures of unethical or illegal behaviour.

2.5 Recent studies

An overview of the literature would not be complete without looking briefly at recent studies in business ethics.

2.5.1 Eth ics Resource Centre national business ethics survey of Fortune 500 companies

In the survey conducted in June 2012, involving 2172 employees from American companies with the highest annual revenue, the ERC found that ethics programmes of Fortune 500 companies are comprehensive and effective and ethical commitment is strong in comparison to other American companies. Fortune 500 companies face a higher risk of stress and misconduct than other companies. Reporting of misconduct is also higher at these companies with employees preferring to report internally but going outside if the company does not respond. The survey further demonstrates a need to improve reward systems so that good conduct is rewarded and unethical behaviour is penalised.

2.5.2 Eth ics Institute of South Africa (EISA) - South African Corporate Ethics Indicator (SACEI)

In comparison, the study by EISA conducted in 2009 had the following key findings: most South African companies have a Code of Ethics, however, it is not sufficiently communicated to employees; ethics management structures and processes need further enhancement; scepticism exists among employees regarding ethical leadership and the resilience of the ethical environment within companies to withstand ethical compromise and, also, that employees are dissatisfied with responses they receive from their companies when they speak up about unethical behaviour. The recom-menddations of the study include the following: the need to improve communication and training on Codes of Ethics as well as ethics policies and management of ethics; and the need for leaders to set the tone by visibly and audibly committing themselves to the company's ethical standards. The study also calls for companies to make ethical behaviour part of their identity and to demonstrate to staff members that reports of risky behaviour are appreciated and taken seriously (Irwin, 2011).

The reports on the ERC and SACEI studies illustrate trends in business ethics and identify strategies for promoting ethical practices in organisations.

This literature study has highlighted certain variables that are critical to establish and maintain an ethical organisational environment. These variables include organisational ethics interventions, elements and characteristics of an ethical organisational environment, ethics standards, infrastructure and practices, principles of good corporate governance, and whistleblowing.

An overview of the research design employed in this study follows, and includes discussion of the following: research methods, sampling, the research instrument, data collection, analysis procedures, and the validity and reliability of the research.

3 Research design

3.1 Purpose of study

The aim of the study was to determine the degree to which ethics related interventions contribute to establishing and maintaining an ethical organisational environment within organisations operating in the Eastern Cape automotive industry. The study focused on the key aspects of business ethics, ethical corporate governance, the legislative environment and organisational values, and their link with ethical behaviour. Following the analysis of the internal ethical environments of organisations in the sample, the article focuses on the key findings of the study with regard to strategies and interventions for improving ethical behaviour.

3.2 Hypotheses

This led the researchers to develop a research question:

To what extent do ethics-related interventions contribute to establishing and maintaining an ethical organisational environment?

Based on the research question, the following hypotheses were constructed and tested:

H1: Organisations in the automotive industry cluster are highly ethical.

H1A: Organisations in the automotive industry cluster have the required infrastructure in place to support an ethical environment.

H1B: Organisations in the automotive industry cluster display high levels of good governance.

H1C: Organisations in the automotive industry encourage the disclosure of unethical behaviour.

Tables corresponding to each of the hypotheses are used to present and analyse the results of the study.

3.3 Research methodology

A quantitative approach was selected as it is objective and relatively simple to administer, it offers a speedy method for data collection and it allows for the data collected to be specific and measurable.

3.4 Measuring instrument

A structured, closed-ended questionnaire was used to collect the data. The questionnaire measured the variables highlighted in the literature reviewed as being critical for establishing and maintaining an ethical organisational environment. It comprised three sections: Section A - Biographical Information; Section B - Business Ethics, and Section C - Organisational Values. The data on organisational values are not reported on in this article. A Likert-type rating scale with an unequal 1 - 5 agreement format was selected for sections B and C of the questionnaire. The instrument was based on the questionnaire prepared by Mey (2004) when conducting a study involving companies in the automotive industry cluster in the Eastern Cape. In addition, it was revised and improved upon according to the literature that was reviewed. With respect to the section on 'business ethics', the first 20 questions related to the following: 'ethics-related standards, infra-structure and practices or culture', which included questions on the person/s responsible for ethics in the organisation, code of ethics, ethics training, ethics audits and commitment to business ethics. These were followed by 26 questions on 'ethical issues pertaining to staff' (including working conditions, recruitment and selection, discrimination, gifts, gratuities and entertainment and social media) 'customers' (including fair pricing and aftersales service), 'shareholders' (including protection of investment), 'suppliers' (including settling of bills and bribery) and 'societal' issues which included questions on environmental protection and sponsorship and donations. The final 50 questions in Section B concentrated on external governance issues, most notably the King Reports I, II and III, and legislation relating to the establishment of a Social and Ethics Committee, and the Protected Disclosures Act and its implications for whistleblowing.

An online questionnaire was selected to increase the response rate. The questionnaire was published on the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University's (NMMU) web survey site which respondents could access electronically via a link provided in the email that was sent to them. To encourage honesty, it was emphasised that the data collected would be treated confidentially and that the respondents would not be personally identifiable.

As the study involved human subjects, ethical clearance was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee (Human) (REC-H) of the NMMU prior to the commencement of the study. Additionally, respondents were requested in the cover letter to report any ethical concerns or issues to the chairperson or secretary of the REC-H.

3.5 Data collection

Primary data was collected by means of a questionnaire while secondary data sources comprised books, journals and electronic databases.

A closed-ended questionnaire was used as this is less time consuming for the individual completing it. A pilot study was conducted among 17 companies operating in the Eastern Cape automotive industry, out of which ten individuals responsible for business ethics and organisational values within their companies responded to the questionnaire. Feedback from the pilot study was incorporated into the questionnaire before it was more widely disseminated.

3.6 Sampling method

The target population for the study comprised 178 companies involved in the Eastern Cape automotive industry that were listed as members of the Automotive Industry Development Centre (AIDC) and/or the Nelson Mandela Bay Business Chamber (NMBBC). However, due to closures, mergers and acquisitions, the population for the study was reduced to 100 companies, all of which were sampled. Therefore, the cover letter and the link to the questionnaire were mailed electronically to 100 companies, including those that had participated in the pilot study. The units of analysis for the study were individuals, one from each company (Chief Executive Officers, Directors, Human Resource professionals and Line Managers) who were responsible for business ethics and organisational values in their companies.

Following the dissemination of the initial email, weekly follow-ups with the companies were done by telephone and email. The final response rate for the study was 46 per cent, which is regarded as acceptable for an email study and particularly one that utilised data collection from organisations (Baruch & Holtom, 2008; Nulty, 2008). Furthermore, the researchers found no reason to doubt that the responses obtained were representative of the population. Due to the lack of access to information regarding the demographic information of the companies, no comparison to average demographics of the population could be made.

3.7 Data analysis

Statistica Version 10 and SPSS Version 20 software packages were used to do the analysis of the data. The respondents' responses were numbered from 1 to 46 while the questions were labelled according to their appearance on the questionnaire. The data collected was subjected to extensive statistical analyses, including Cronbach Alpha coefficients and various descriptive statistics, in particular, means and standard deviations in order to provide a quantitative summary of the sample. With a specific calculated constant reference value, the significance of the tested variables to the study could be inferred.

3.8 Validity and reliability of the research

Validity was ensured by reviewing literature relating to the research as well as through the use of an appropriate questionnaire generated from aspects highlighted in the literature reviewed.

In order to ensure the reliability of the questions asked in the questionnaire, they were designed to be as simple as possible and understandable for the intended sample. In addition, all respondents were required to answer the same questions.

4 Data analysis and interpretation of results

4.1 Introduction

Through the identified supporting factors and Cronbach Alpha values attached to each supporting factor, the reliability of the study was verified. The response rate for the study of 46 per cent was regarded as acceptable for an email study, and particularly for one that utilised data collection from organisations (Baruch & Holtom, 2008; Nulty, 2008). Despite the small size of the sample of 46, an extensive analysis was conducted to assist the research process to make meaningful deductions and to emphasise that the study was mainly exploratory in nature. Due to the small sample and the large number of relevant individual items identified (linked to the identified supporting factors), an item reliability analysis was pursued. The results of the calculated Cronbach Alphas and the ensuing statistical tests are given in the tables below to illustrate the internal reliability and the consistency of the tested constructs of the analysis.

4.2 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 illustrates the reliability of the measure of the various factors that were identified as supporting structures to the development of an ethical organisational environment; this is reflected by the high Cronbach Alpha value and is, furthermore, supported by mainly high individual item total correlations. Furthermore, this is supported by the relatively high total mean scores attached to each of the identified supporting factors.

4.3 Descriptive statistics and item reliability analysis

Table 2 reflects the individual items collectively labelled ethics interventions, and it forms part of the broader hypothesis dealing with infrastructure to support ethics interventions.

The factor as identified in Table 2 is related to the hypothesis dealing with infrastructure to support ethical behaviour (Hypothesis H1A).

Table 3 expounds the individual items dealing with the elements of an ethical organisational environment and is also linked with Hypo-thesis H1A, dealing with required infra-structure to support an ethical environment which correlates better with the ethics interventions factor as reflected in Table 2.

Table 4 reflects the individual items dealing with the characteristics of an ethical organisational environment (Hypothesis H1A).

In testing the H1A hypothesis, the mean values of all the individual items relating to the hypothesis ranged between the categories of high to very high on the selected rating scale (see Tables 2, 3, 4).

This is supported by the majority of the in individual total item correlations, as reflected Tables 2, 3, 4.

Note 1:

In terms of the item dealing with ethics coordination being the responsibility of top management, it was hypothesised that if more than 75 per cent of the sample respondents agreed with this statement, then it would be logical to argue that the Eastern Cape automotive industry cluster views the function of coordinating the ethics as being the responsibility of top management. Therefore

Ho:π = 0.75

H1:π > 0.75

Given the results from the statistical test, with a Z score of 1.86 and a resulting p-value of 0.0314, it becomes clear that a significantly larger proportion of respondents (more than 75 per cent of the sample) agreed that coordinating ethics is the responsibility of the top management.

These items labelled as ethics standards, infrastructure and practices deals with the relevance and implementation of the Code of Ethics, as a tool for creating a more ethical organisational culture.

Table 6 reflects the items labelled as principles of good corporate governance used by respondents in the Eastern Cape automotive industry cluster.

These items and the identified factor are linked to Hypothesis H1B. In testing this hypothesis, the mean value of each of the individual items ranks high on the selected rating scale. The same applies to the item total correlation values which indicate support towards this hypothesis.

The individual item labelled as whistleblowing is related to Hypothesis H1C. This hypothesis is also in part supported by high individual item-total correlation values, except in the case of the organisation offering incentives to people reporting illegal behaviour and the organisation making changes to corporate governance following complaints. In the latter case, this factor correlates more optimally with the principles of good governance (see Table 6).

4.4 Statistical tests

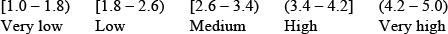

The selected rating scale used in this study is derived from a five-point rating with differing discrete intervals as is reflected below:

The mathematical parentheses used indicate 'value included' in the case of a square bracket and 'value excluded' in the case of a round bracket. By using this scale, a more accurate reflection and rating mechanism is generated either to support or not to support the stated hypotheses of the study.

The statistical tests in Table 8 indicate that the calculated mean value (4.12) for 'Ethics interventions' is significantly larger than the reference constant value of 3.4. It is also indicated that the result is statistically significant as is reflected in the respective tand p-value as expounded in Table 8. The practical significance of the individual items dealing with ethics interventions is also substantiated by the very high Cohen's d-value of 1.04.

The calculated mean value of 4.5 for 'Elements of an ethical organisational environment' is significantly larger than the reference constant value of 3.4. This is supported by the relevant t- and p-values. The practical significance of the combined items dealing with elements of an ethical organisation's environment is also underpinned by the exceptionally high Cohen's d-value of 1.88.

The individual items dealing with the 'Characteristics of an ethical organisational environment' has a mean value of 4.22 (see Table 8), which also measures on the high to very high range of the measuring scale. In all the aforementioned cases, the majority of the individual mean values support the average mean values of the various factors. This result is supported by the relevant t- and p-values. The practical significance of this factor is also high at 1.42.

The statistical tests indicate that the calculated mean value (4.04) for 'Ethics standards, infrastructure and practices' is significantly larger than the constant reference value of 3.4. It is also indicated that the results are statistically significant as is reflected in the respective t- and p-values shown in Table 8.

The practical significance of the combined items called ethics standards, infrastructure and practices are also substantiated by the Cohen's d-value of 0.68, which places it at medium strength.

It can therefore be stated that the hypothesis dealing with infrastructure requirements to support an ethical environment is supported by the data, revealing that organisations in the automotive industry cluster have the required infrastructure in place to support an ethical environment.

The statistical data indicates that the calculated mean value (3.96) for 'Principles of good governance' is significantly larger than the reference constant on the selected rating scale. It is further indicated that the results are statistically significant as is reflected in the respective t- and p-values. Cohen's d-value also reflects the practical significance of the result and in this case the practical significance is between medium (0.5) and high (0.8).

It can therefore be stated that the hypothesis dealing with principles of good governance is supported by the data, revealing that organisations in the automotive industry cluster display high levels of good governance.

The statistical analysis of Table 8, furthermore, indicates that the calculated mean value of 3.69 for 'Whistleblowing' is larger than the constant reference value of 3.4.

It is also shown in T able 8 that the result is statistically significant due to the respective tand p-values. On the other hand, Cohen's d-value is low at 0.3 indicating a low practical significance of the result (0.2 being low and 0.5 being medium on the Cohen's d-scale).

The hypothesis dealing with the disclosure of unlawful behaviour in the automotive industry is supported by the data, indicating that organisations in the automotive industry cluster encourage the disclosure of unlawful conduct via whistleblowing.

5 Recommendations

The results of the study support the primary hypothesis that organisations in the automotive industry cluster are highly ethical. This may be attributed to, and further encouraged by, six areas of policy and practice.

5.1 Ethics-related standards, infrastructure and practices

Eighty-five per cent of organisations have a person responsible for ethics, fifty-six per cent have a Code of Ethics in place and a further 11 per cent responded that one was being implemented. More than 85 per cent of the respondents reported that the leadership and management of their organisations were committed to ethical business objectives and practices and the majority of organisations had clear policies and guidelines regarding acceptable ethical behaviour for all stakeholders (employees, customers, suppliers and share-holders).

5.2 High levels of corporate governance

More than 70 per cent of respondents indicated that their organisations displayed the principles of good governance, namely: discipline, transparency, independence, accountability, responsibility, fairness and social responsibility.

5.3 Encouragement of the disclosure of unethical behaviour

Eighty-five per cent of respondents stated that their organisations encouraged and recognised the disclosure of unlawful acts, wrongdoings and deviant behaviour.

While the ethical conduct of the organisations in the sample is commendable, the following improvements are recommended:

5.4 Training and communication

As only 35 per cent of the respondents' organisations currently provide training in business ethics, this is an area that warrants attention. It is recommended that training and communication include ethics related company policies and codes, such as the Code of Ethics, and legal provisions, such as those pertaining to whistleblower protection, as identified by Irwin (2011).

5.4 Ethics audits

Seventy-one per cent of companies did not conduct ethics audits to assess the ethical environment. If ethics is not being measured, it cannot be managed. Regular ethics audits to identify potential 'hot spots' are therefore highly recommended.

5.5 Ethics focused rewards

While a high percentage of respondents (85 per cent) indicated that their organisation encouraged the disclosure of unethical behaviour, only 26 per cent of the respondents' organisations offered incentives to those that report unethical or unlawful practices. Fifty-six per cent of respondents agreed that their organisations offered support and protection over and above legal provisions. Offering rewards, financial and otherwise, will incenti-vise more employees to come forward especially if this is backed up by a sound knowledge of the protection afforded to them legally and by the organisation.

5.6 Social and ethics committee

A Social and Ethics Committee, as provided for by the Companies Act No. 71 of 2008, was present in about 30 per cent of the organisations. This needs to be addressed as it is not only a legal requirement, but affords organisations the opportunity to elevate social and ethical obligations to a strategic board level.

6 Limitations of the study

A possible limitation of the study is that the sample size of 46, while being adequate for statistical analysis, may restrict the ability to generalise the findings beyond the related hypotheses. Also, all 46 respondents were drawn from the automotive industry in the Eastern Cape. Further research with a larger sample size, across different sectors and geographical areas, would add value and improve the generalisability of this research.

7 Conclusion

Corporate indiscretion, wrongdoing and corruption are frequently the subject of international media attention, with unethical business practices creating undesirable and expensive problems for organisations. Highprofile scandals have brought about a renewed interest in business ethics and, in particular, in understanding the factors that promote ethical behaviour. Against this background, the present study was conducted to measure and analyse the ethical practices of organisations operating in the Eastern Cape automotive industry. The results of the study reveal that the organisations in the sample are in fact highly ethical. In keeping with international best practice, the study also validates the presence of ethics-related interventions, such as a Code of Ethics, committed leadership, clear policies and codes for stakeholders, and encouragement of the disclosure of unethical behaviour. These factors contribute to establishing and maintaining an ethical organisational environment.

References

ANONYMOUS, 2013. MTN slapped with $4.2bn Turkcell lawsuit. Mail & Guardian, 27 November 2013. Available at: http://mg.co.za/article/2013-11-27-turkcell-takes-mtn-to-court-for-losses-incurred [accessed 2014-03-10]. [ Links ]

ARCHER, D. 2008. Ensuring an ethical organisation. CMA Management, November 2008:32-36. [ Links ]

BAINBRIDGE, R. 2007. Whistleblower definition. Available at: http://ezinearticles.com/?Whistleblower-Definition&id=410263 [accessed 2013-03-15]. [ Links ]

BARNARD, L.D. 2012. Assessing some aspects of managerial ethics within the South African business environment. Master's in Business Administration mini dissertation. North-West University. [ Links ]

BARUCH, Y. & HOLTOM, B.C. 2008. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Human Relations, 61(8): 1139-1160. Available at: http://www18.georgetown.edu/data/people/bch6/publication-39527.pdf [accessed 2014-03-10]. [ Links ]

BUSINESSDICTIONARY.COM. Available at: http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/corporate-governance.html [accessed 2012-10-09]. [ Links ]

CHAUHAN, D. & CHAUHAN, S.P. 2002. Ethical dilemmas faced by managers: some real life cases. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 37(3):370-385. [ Links ]

COMPANIES ACT 71 OF 2008. Available at: http://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/acts/2008-071amended.pdf [accessed 2014- 03-10]. [ Links ]

ELANGO, B., PAUL K., KUNDU, K.S. & PAUDEL, S.K. 2010. Organizational ethics, individual ethics and ethical intentions in international decision making. Journal of Business Ethics [e-journal], [ Links ] 97:543-561. Available through: EBSCOhost database academic search premier [accessed 2012-09-10].

ETHICS RESOURCE CENTRE [ERC]. 2012. National business ethics survey of fortune 500 employees. Available at: http://www.ethics.org/nbes/ [accessed 2012-10-10]. [ Links ]

FIESER, J. n.d. Business ethics. 2012. Available at: http://rio.mhs.narotama.ac.id/2012/01/02/tugas-personal-business-ethics-by-james-fieser/ [accessed 2012-10-10]. [ Links ]

FOMBRUN, C. & FOSS, C. 2004. Business ethics: Corporate responses to scandal. Corporate Reputation Review, 7(3):284-288. [ Links ]

FREEMAN, R.E. & REED, D.L. 1983. Stockholders and stakeholders: A new perspective on corporate governance. California Management Review, 25(3):88-106. [ Links ]

FREEMAN, R.E. 2001. Stakeholder theory of the modern corporation. Available at: http://academic.udayton.edu/lawrenceulrich/Stakeholder%20Theory.pdf [accessed 2014- 03-10]. [ Links ]

GANDZ, J. & HAYES, N. 1988. Teaching business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 7:657-669. [ Links ]

GRANGER, D. 2011. 5 Steps to building an ethical culture. Available at: http://blog.rogerscorp.com/2011/08/02/5-steps-to-building-an-ethical-culture/ [accessed 2013-03-05]. [ Links ]

GRUBLE, C. 2011. Defining business ethics. Business Ethics Review. Available at: http://businessethicsreview.wordpress.com/2011/06/21/defining-business-ethics/ [accessed 2013-03-05]. [ Links ]

INSTITUTE OF DIRECTORS SOUTHERN AFRICA. 2009. King code of governance for South Africa 2009. Available at: http://www.ecgi.org/codes/documents/king3.pdf [accessed 2012-10-10]. [ Links ]

IRWIN, J. 2011. Doing business in South Africa: An overview of ethical aspects. Available at: http://www.ibe.org.uk/userfiles/op4%20final.pdf [accessed 2012-10-09]. [ Links ]

JOSEPHSON, M. 2012. Business ethics insight: The three levels of ethical issues in business. Available at: http://josephsoninstitute.org/business/blog/2012/07/business-ethics-insight-the-three-levels-of-ethical-issues-in-business/ [accessed 2013-03-05]. [ Links ]

JOYNER.B.E. & PAYNE, D. 2002. Evolution and implementation: A study of values, business ethics and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 41:297-311. [ Links ]

KNIGHTS, D. & O'LEARY, M. 2005. Reflecting on corporate scandals: The failure of ethical leadership. Business Ethics: A European Review, 14(4):359-366. [ Links ]

LEWIS, P.V. 1985. Defining 'business ethics': Like nailing jello to the wall. Journal of Business Ethics, 4: 377-383. [ Links ]

LLOYD, H. & MEY, M.R. 2010. An ethics model to develop an ethical organisation. South African Journal of Human Resources Management, 8(1):1-12. Available at: http://www.sajhrm.co.za/index.php/sajhrm/article/view/218/252 [accessed 2012-10-10]. [ Links ]

MAYER, D.M. 2011. How can we create ethical organizations? Available at: http://www.centreforpos.org/2011/07/how-can-we-create-ethical-organizations/ [accessed 2012-10-09]. [ Links ]

MEY, M.R. 2004. The development of a human resource model that supports the establishment of an ethical organisational culture. Doctor Technologiae thesis, Port Elizabeth Technikon. [ Links ]

MIETHE, T.D. & ROTHSCHILD, J. 1994. Whistleblowing and the control of organizational misconduct. Sociological Inquiry, 64(3):322-347. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1994.tb00395.x/abstract [accessed 2014-03-10]. [ Links ]

NULTY, D.D. 2008. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(3):301-314. Available at: http://www.uaf.edu/files/uafgov/fsadmin-nulty5-19-10.pdf [accessed 2014-03-12]. [ Links ]

PATTAN, J.E. 1984. The business of ethics and the ethics of business. Journal of Business Ethics [e-journal], [ Links ] 3:1-19. Available through: EBSCOhost database academic search premier [accessed 2012-09-10].

PROTECTED DISCLOSURES ACT 26 OF 2000. Available at: http://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/acts/2000-026.pdf [accessed 2014-03-11]. [ Links ]

RILEY, J. 2012. Business ethics in practice. Available at: http://www.tutor2u.net/business/gcse/external_environment_business_ethics_in_practice.html [accessed 2012-10-09]. [ Links ]

ROBBINS, S.P. & JUDGE, T.A. 2009.Organizational behaviour (13th ed.) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. [ Links ]

ROSSOUW, D. & VAN VUUREN, L. 2010. Business ethics (4th ed.) Southern Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

ROSSOUW, D. & VAN VUUREN, L. 2013. Business ethics (5th ed.) Southern Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

SCHOEMAN, C. 2012a. How ethical is South Africa? Ethical Living. Available at: http://www.ethicsmonitor.co.za/Articles/064-065.pdf [accessed 2012-10-10]. [ Links ]

SCHOEMAN, C. 2012b. Good ethics makes good business sense. HR Future, May 2012:38. Available at: http://www.ethicsmonitor.co.za/Articles/GoodEthics.pdf [accessed 2012-10-10]. [ Links ]

SELIGSON, A.L. & CHOI, L. 2006. Critical elements of an organizational ethical culture. Ethics Resource Centre Research Report. Available at: http://www.workingvalues.com/Dec06WorkingValuesWhtPpr.pdf [accessed 2014-03-11]. [ Links ]

VAN VUUREN, L.J. 2002. Institutionalising business ethics: a multi-level strategy. Management Dynamics, 11(2):21-27. Available at: http://reference.sabinet.co.za/document/EJC69643 [accessed 2014-03-11]. [ Links ]

VAN ZYL, E. & LAZENBY, K. 1999. Ethical behaviour in the South African organisational context: Essential and workable. Journal of Business Ethics, 21:15-22. [ Links ]

VERSCHOOR, C.C. 1998. A study of the link between a corporation's financial performance and its commitment to ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 17:1509-1516. [ Links ]

VICTOR, B. & CULLEN, J.B. 1988. The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(1):101-125. [ Links ]

ZGHEIB, P.W. 2005. Managerial ethics: An empirical study of business students in the American University of Beirut. Journal of Business Ethics, 61:69-78. [ Links ]

ZONA, F., MINOJA, M. & CODA, V. 2013. Antecedents of corporate scandals: CEOs' personal traits, stakeholders' cohesion, managerial fraud and imbalanced corporate strategy. Journal of Business Ethics, 113: 265-283. [ Links ]

Accepted: May 2014