Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versión On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.17 no.4 Pretoria abr. 2014

The dimensions of brand romance as predictors of brand loyalty among cell phone users

Danie Petzer; Pierre Mostert; Liezl-Marie Kruger; Stefanie Kuhn

WorkWell: Research Unit for Economic and Management Sciences, North-West University

ABSTRACT

In a competitive cell phone industry where consumers have a wide variety of cell phone brands to choose from, it is imperative for marketers to foster brand loyalty in order to establish enduring consumer-brand relationships. Nurturing brand romance has been suggested to marketers to cultivate emotional attachments between consumers and brands so as to increase brand loyalty. This study focussed on determining the extent to which the three underlying dimensions of brand romance, namely pleasure, arousal and dominance predict brand loyalty among cell phone users in the North West province. In total 371 respondents participated in the study. Results indicate that with respect to brand romance, respondents' current cell phone brands generate brand pleasure and brand arousal, but that these brands are not dominant in their minds. Although respondents participating in the study did not exhibit strong levels of brand loyalty towards their current cell phone brands, the three underlying dimensions of brand romance are statistically significant predictors of brand loyalty

Key words: brand romance, brand arousal, brand pleasure, brand dominance, brand loyalty, cell phone industry, cell phone brands

1 Introduction

It has been argued that consumers' emotions result in the formation of emotional attachments with brands (Round & Roper, 2012: 941), which in turn fosters long-term relationships with these brands (Long-Tolbert & Gammoh, 2012:391). Studying consumer emotions is thus important as emotional attachment in consumer-brand relationships is said to move consumers to become active partners in their relationships with brands (Belaid & Behi, 2011:43; Kaufmann, Loureiro, Basile & Vrontis, 2012:406). When consumers engage with brands in this way, it becomes less expensive and more profitable for marketers to maintain consumer-brand relationships (Hess, Story & Danes, 2011:16, 22). Insights into consumer-brand relationships that increase brand loyalty could therefore be of value to academics and practitioners alike (Ismail & Spinelli, 2012:387).

Sarkar (2011:80) articulates that although traditional branding research conceptualises satisfaction to exert a direct impact on brand loyalty, satisfaction alone does not lead to brand loyalty. Subsequently, marketers need to consider alternative means of fostering brand loyalty, such as consumers' interaction with a brand in the endeavour of forming emotional attachments (Patwardhan & Balasubramanian, 2011:298). Emotional attachments leading to consumer-brand relationships should therefore be investigated and brand romance is considered to be such an emotional attachment (Patwardhan & Balasubramanian, 2011:299). Based on their research findings, Patwardhan and Balasubramanian (2011:299) advocate that three dimensions should be considered when investigating brand romance, namely pleasure, arousal and dominance. The purpose of this study was therefore to determine the extent to which the three underlying dimensions of brand romance predict brand loyalty among cell phone users in South Africa's North West province.

Cell phone users were chosen since, as Li, Dong and Chen (2012:121) suggest, emotions play a central role in cell phone users' experiences because consumers experience a variety of emotions during the daily use of their cell phones. This view is supported by Tsai (2011:531 -532) who suggests that products (such as cell phones) could create an attachment that can be used for relationship building purposes by offering sensory pleasure and emotional and intellectual delight (for example, cell phones could be used for entertainment purposes) while simultaneously conveying symbolic meaning that consumers use to reinforce or express their identity (such as using cell phones for social networking purposes). Cell phones are therefore no longer only a communication device, as is evident by the fact that cell phones are being used in a variety of ways for different purposes and experiences, all evoking emotions through utilitarian (for example mobile banking) and hedonic (for example gaming) components (Li et al., 2012:121, 135; Petruzzellis, 2010:615). Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001:82, 88), Holbrook and Hirschman (1982:138-139) and Kim (2012: 425) accordingly argue that hedonic consumption (referring to the positive feelings associated with the enjoyment derived from consumption) results in brand loyalty. In summary it can be concluded that the fast development of new technologies and applications within the cell phone industry, and cell phone handsets in particular, emphasises the importance of fostering consumer-brand relationships (Franzak & Pitta, 2011:396) to not only create brand loyalty (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001:82, 85; Thorbjørnsen, Supphellen, Nysveen & Pedersen, 2002:20; Wang & Li, 2012:149, 164, 170), but also to prevent customers from switching to competitors (Hoyer, Maclnnis & Pieters, 2013:252; Wang & Li, 2012:149).

2 Theoretical overview

2.1 Brand loyalty

Brand loyalty can be viewed as consumers' repetitive and systematic purchase of the same brand (Belaid & Behi, 2011:39). For true brand loyalty to exist, consumers have to form an emotional attachment with (Liu, Li, Mizerki & Soh, 2012:924), and be committed to the brand (Wilson, Zeithaml, Bitner & Gremler, 2012: 41).

Chitty, Hughes and D'Alesandro (2012: 232), Petruzzellis (2010:616) and Torres-Moraga, Vásques-Parraga and Zamora-González (2008: 303) argue that brand loyalty is created by establishing and maintaining consumer-brand relationships. The reason why organisations want to establish and maintain brand loyalty is clear: brand loyalty is imperative for successful financial performance (Castro & Pitta, 2012:126; Delgado-Ballester & Munuera-Alemán, 2001:1238; Kuikka & Laukkanen, 2012:534; Torres-Moraga et al., 2008:303). Other advantages of pursuing brand loyalty include the fact that brand-loyal consumers are less price-sensitive (Delgado-Ballester & Munuera-Alemán, 2001:1254; Hawkins & Mothersbaugh, 2013:680), they act as effective ambassadors for the brand (Hess et al., 2011: 14), and they are less likely to be influenced by competitors' marketing efforts or to switch to competitors (Hoyer et al., 2013:252; Wang & Li, 2012:149). Brand loyalty thus results in reduced marketing costs and an increased share of consumers' spending (Gummesson, 2002:52), critical for cell phone marketers in a fiercely competitive market where it is easy to switch between brands (Tubbs, 2012; UNICEF, 2012:6).

To consumers, brand loyalty provides confidence that the brand to which they are loyal will satisfy their needs better than competing brands (Day, 1969:34). This confidence is instilled through intangible benefits inherent in the brand (Torres-Moraga et al., 2008:308), resulting in consumer-brand relationships (Lazarevic, 2012:55-56). Consumer-brand relationships that increase brand loyalty are thus of importance to both academics and practitioners (Ismail & Spinelli, 2012:387). Oliver (1999:39) explains that the value of pursuing consumer-brand relationships lies therein that some forms of consumer-brand relationships result in a sense of enduring attachment. For this reason, an emotional attachment is necessary for consumers to act as partners in consumer-brand relationships (Long-Tolbert & Gammoh, 2012:391).

Brand attachment can be defined as a deep-seated passion for the brand and is characterised by consumers determined to possess the brand and a willingness to make sacrifices for this purpose (Tsai, 2011:531). Emotions thus contribute to establishing brand attachment. Considering emotional (or affective) aspects when trying to build brand loyalty is therefore important as brand attachment positively impacts brand loyalty (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001:82, 85; Hwang & Kandumpully, 2012:103, 105; Papista & Dimitriadis, 2012: 48). Although it was found that brand attachment had a greater impact on brand loyalty than brand commitment (Tsai, 2011: 530-531), previous research also established that brand attachment indirectly affects brand loyalty through impacting brand commitment (Belaid & Behi, 2011:43) and brand trust (Belaid & Behi, 2011:43; Song, Hur & Kim, 2012:337). Patwardhan and Balasubramanian (2011:299, 304) have established brand romance as an emotional attachment to the brand which does affect brand loyalty.

2.2 Brand romance

According to Patwardhan and Balasubramanian (2011:304) a need exists to investigate the effect of brand romance within consumer-brand relationship research. Based on the findings of their research, Patwardhan and Balasubramanian (2011:299) advocate that three underlying dimensions should be considered when determining brand romance, namely pleasure, arousal and dominance.

Li et al. (2012:136) and Mugge, Schifferstein and Schoormans (2010:279) state that consumer-brand relationships are rooted in pleasure. For this reason, Patwardhan and Balasubramanian (2011:299) argue that brand romance also starts with pleasure. Since a particular level of pleasure as opposed to displeasure can be used to determine satisfaction (Oliver, 1999:34), cell phone marketers should provide satisfactory brands to stimulate emotional bonding and elicit pleasure (Mugge et al., 2010:279). Although positive emotional responses to brands have been termed brand affect (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001:82), this study considers the association of positive feelings toward brands as pleasure, the label used by Patwardhan and Balasubramanian (2011:299) when examining this particular dimension of brand romance. The pleasure dimension of brand romance includes an attraction to the brand (Patwardhan & Balasubramanian, 2011: 299). Newman and Werbel (1973:404) considered consumer attraction to the brand as an important dimension of brand loyalty. Pleasure could thus affect brand loyalty (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001:82, 88; Kim, 2012:431; Mugge et al., 2012:279; Ye, Bose & Pelton, 2012:198). For this reason, the possible impact of the pleasure dimension of brand romance on brand loyalty becomes evident.

Considering emotional responses to consumption, arousal also directly influences consumers' actual purchase behaviour (Li et al., 2012:135). Emotional arousal (which extends beyond affect or preference) can be the motivation for consumption, since consumers become involved with the brand (Holbrook & Hirchman, 1982:93; 133). Such intense positive feelings causing arousal constitute the second dimension of brand romance, labelled as arousal (Patwardhan & Balasubramanian, 2011: 299). Emotions, such as pleasure and arousal, affect consumers' activity, intention and reaction with regard to consumption behaviour (Li et al., 2012:135) as well as brand loyalty (Dick & Basu, 1994:104; Kuikka & Laukkanen, 2012: 531, 534).

According to Patwardhan and Balasu-bramanian (2011:299) the last dimension of brand romance, namely dominance, captures the brand's propensity to engage the consumer's cognition. Brands consumers use become part of their lives (Fournier, 1998:367) and can become so imbedded in consumers' lives that they form part of their psyche and lifestyle (Oliver, 1999:40). The cognitive nature of consumer-brand identification results in brand loyalty when congruence between consumers' self-images and the brand exist and the brand becomes embedded in consumers' lives (Oliver, 1999:38, 40; Papista & Dimitriadis, 2012:47; Ye et al., 2012:197-198). In the cell phone industry specifically, consumers are attached to their cell phones (Hollis, 2011:7; Orrill, 2011:48) as cell phones are regarded as extensions of one's identity (Du Toit, 2011: 40).

In summary, brand romance is considered in terms of three underlying dimensions referring to emotions (such as pleasure and arousal) and dominance (where the brand can become imbedded in consumers' lives) (Patwardhan & Balasubramanian, 2011:299). According to Tsai (2011:530) brand loyalty is established through holistically considering the utilitarian, emotional and symbolic (congruence with self-image and social image) value of the brand. Even though Patwardhan and Balasubramanian (2011:304) maintain that brand romance predicts brand loyalty, the underlying dimension of brand romance should, for this reason, also predict brand loyalty.

3 The South African cell phone industry

The South African cell phone industry has experienced tremendous growth, especially due to cell phone network providers offering prepaid subscriptions to resource-limited consumers (UNICEF, 2012:5; 12) since the launch of cellular services by Vodacom and MTN in 1993 (Vodacom, 2013; MTN, 2013). Such was the growth that it is believed that the country today enjoys more than 100 per cent market penetration (African Telecoms News, 2012: 20; UNICEF, 2012:5), with more than 51 million active cellular subscriptions (Blycroft, 2012). In terms of revenue, the cellular industry generated more than 60 per cent of the income of the total telecommunications industry in 2010, namely R118 billion (Stats SA, 2010:2).

Cell phones increasingly form an integral part of South African consumers' daily lives (SAARF, 2012; Bohlmann, 2011), as is evident from the amount of time consumers spend interacting with their cell phones (Persuad & Azhar, 2012:418). Advancement in South African cellular technologies also increases consumers' reliance on cell phones as a platform for conducting mobile commercial transactions (ranging from mobile payments and mobile-banking to flight and hotel reservations), thereby contributing to the increased time consumers spend interacting with their cell phones (Dlodlo & Chengadzai, 2013:2).

Additionally, South Africa's cell phone sales accounted for 21 per cent of all consumer electronics spending in 2010 (UNICEF, 2012: 13). According to Fripp (2012) and Hutton (2011), Nokia, BlackBerry and Samsung are the three most popular cell phone brands in South Africa. In terms of usage behaviour, Goldstuck (cited in Vermeulen, 2012) estimated that more South Africans access the internet via their cell phones than those doing so by personal computer, laptops and tablet PCs combined. The majority of South African cell phone users also prefer sending SMS text messaging to calling (Hutton, 2011).

In order to establish and maintain a competitive advantage in this competitive industry, it is important for cell phone handset marketers to build relationships with their customers in order to retain them in a market characterised by fierce competition where it is easy to switch between brands (Tubbs, 2012; UNICEF, 2012:6).

4 Problem statement, objectives, hypotheses, and conceptual framework

In a competitive cell phone industry where consumers have a wide variety of cell phone brands to choose from, it is imperative for marketers to ensure that their brands relate to consumers on a personal level. By forming consumer-brand relationships, marketers can limit switching behaviour and strengthen brand loyalty (Franzak & Pitta, 2011; Hoyer et al., 2013; Wang & Li, 2012), thereby reducing marketing costs and increasing the share of consumers' spending (Gummesson, 2002:52).

Although numerous research studies focussed on satisfaction as a mediator accounting for the relationship between numerous constructs and loyalty (Aksoy, Buoye, Aksoy, Larivière, & Keiningham, 2013; Jeon & Hyun, 2012; Tu, Wang, Chang, 2012), most studies conclude that satisfaction alone does not lead to brand loyalty (Dagger & David, 2012; Drenger, Jahn & Gaus, 2012; Sarkar, 2011). Consequently, recent branding studies focussed on the mediating role of emotional attachments when long-term relationships with consumers are considered (Hwang & Kandampully, 2012; Long-Tolbert & Gammoh, 2012). While studies suggest that brand romance may forecast loyalty better than brand attitude (Patwardhan & Balasubramanian, 2011:304), empirical evidence regarding the extent to which brand romance and its underlying dimensions predict brand loyalty remains limited.

The primary objective of this study was therefore to determine the extent to which brand romance (in terms of three underlying dimensions, namely pleasure, arousal and dominance) predict brand loyalty among cell phone users in the North West province. The following secondary objectives were accordingly formulated:

- Measure the three underlying dimensions of brand romance, namely pleasure, arousal and dominance with respect to cell phone users' current cell phone brands.

- Determine the level of brand loyally cell phone users exhibit towards their current cell phone brands.

- Determine the extent to which the three underlying dimensions of brand romance, namely pleasure, arousal and dominance predict brand loyally.

The following hypotheses were accordingly formulated:

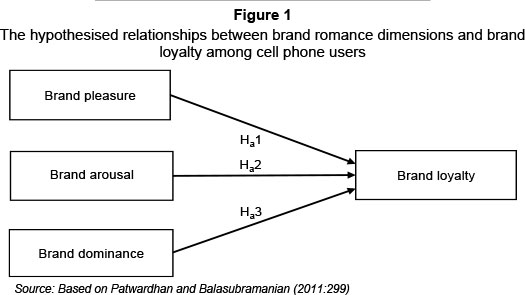

Ha1: Brand pleasure predicts consumers' brand loyally towards their current cell phone brands.

Ha2: Brand arousal predicts consumers' brand loyally towards their current cell phone brands.

Ha3: Brand dominance predicts consumers' brand loyally towards their current cell phone brands.

Based upon the literature and resultant hypotheses, the following conceptual framework is proposed to illustrate the relationships between the variables concerned.

5 Research methodology

5.1 Research design, study population and sampling plan

In order to achieve the objectives formulated for the study, a descriptive research design that is quantitative in nature was followed. The researchers targeted the study population, residents living in the North West province who were older than 18 years, owned a cell phone, and had a say in the purchase of their cell phone. Since a sampling frame of the study population was not available, non-probability sampling techniques were chosen for the study. The researchers utilised convenience sampling to select the sample from the study population. A total of 371 of the 400 questionnaires fielded could be used for analysis.

5.2 Questionnaire

A self-administered questionnaire was designed to collect the data. Screening questions were included to ensure that respondents were eligible to take part in the study. The questionnaire inquired about the demographic characteristics of respondents as well as their cell phone patronage habits. Brand romance was measured using a five-point Likert-type scale with items taken from the research by Patwardhan and Balasubramanian (2011). A five-point Likert-type scale (where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree) was used to measure the three dimensions of brand romance, namely brand arousal, brand pleasure and brand dominance, as well as respondents' brand loyalty towards their current cell phone brand. The brand loyalty measurement scale used seven items adapted from Keller (2001) and used a five-point Likert-type scale (where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree).

5.3 Method of data collection

Honours degree students specialising in Marketing Management (who have all completed a marketing research module) were selected and trained as fieldworkers for this study. It was expected of fieldworkers to select prospective respondents from the target population (based upon convenience, filling a gender quota in all major cities and towns in the North West province), approach them, determine their eligibility to take part in the study, and finally, collect the distributed questionnaires from respondents once completed.

5.4 Data analysis

The researchers made use of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 20 to capture, clean, edit, and analyse the data. Once the data file was ready for analysis, the researchers calculated frequencies to portray a demographic profile of respondents who participated in the study. The researchers furthermore assessed the internal consistency reliability of all the items in the brand romance and brand loyalty scales.

To present the results of the Likert-type scales measuring brand romance and brand loyalty, descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were calculated. Once the reliability of the measurement scales had been established, the researchers calculated overall mean scores for the three dimensions of brand romance and the brand loyalty construct. In order to test the hypotheses formulated for the study, the researchers conducted a standard multiple regression analysis to determine the extent to which the three dimensions of brand romance predict the brand loyalty construct, after it was ensured that assumptions associated with using this technique were met. The researchers furthermore relied on a 95 per cent confidence level to interpret the results.

6 Results

6.1 Demographic profile of respondents

From Table 1 it can be seen that slightly more females (52.6 per cent) participated in the study than males (47.4 per cent). More than a third of the respondents had either completed high school (34.8 per cent) or completed a university or post-graduate degree (35.0 per cent) as their highest qualification. Most respondents were full-time employed (56.6 per cent). Nearly three quarters of the respondents were contract customers (73.3 per cent). Half of the respondents used BlackBerry cell phones (50.0 per cent), followed by Nokia (26.8 per cent) and Samsung (11.4 per cent). The table also shows that the majority of respondents had been using their current cell phone brand for between one and three years (39.1 per cent).

6.2 Brand romance and brand loyalty

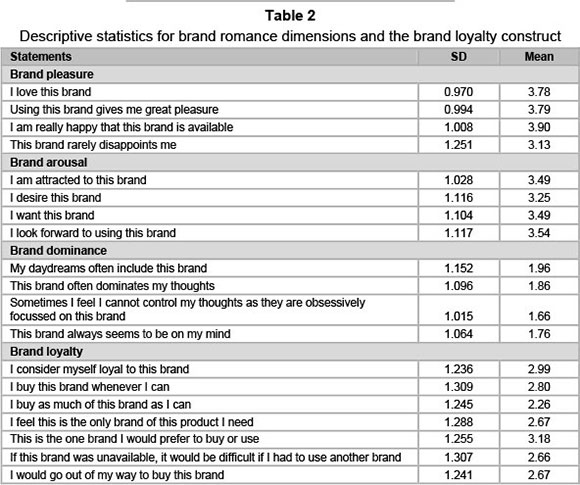

Table 2 presents the standard deviations and means for all the items measuring the underlying dimensions of brand romance and the construct measuring brand loyalty.

From Table 2 it can be seen that the item 'I am really happy that this brand is available' (mean = 3.90) obtained the highest mean of all items measuring brand romance, followed by another two items measuring the brand pleasure dimension of brand romance, namely 'Using this brand gives me great pleasure' (mean = 3.79) and 'I love this brand' (mean = 3.78). The items that obtained the lowest mean scores measure the brand dominance dimension of brand romance and include 'Sometimes I feel I cannot control my thoughts as they are obsessively focussed on this brand' (mean = 1.66) and 'This brand always seems to be on my mind' (mean = 1.76). All items measuring the underlying dimensions of brand pleasure and brand arousal of brand romance obtained means above the midpoint of the scale, namely 3.00 (between 3.13 and 3.90), whilst all items measuring brand dominance obtained means below the midpoint of the scale (between 1.66 and 1.96).

When the items measuring brand loyalty are examined, it is evident that only one item obtained a mean above the midpoint of the scale, namely 'This is the one brand I would prefer to buy or use' (mean = 3.18), with 'I buy as much of this brand as I can' (mean = 2.26) obtaining the lowest mean.

6.3 Assessing reliability and overall mean scores

To assess the internal consistency reliability of the scales used to measure the underlying dimensions of brand romance and the brand loyalty construct, Cronbach's alpha coefficients were calculated and are subsequently presented in Table 3. According to Pallant (2010:6), a coefficient of 0.7 and higher indicates sufficient correlation between the items, indicating that the items measure a particular underlying 'attribute'. Sufficient internal consistency reliability allows for the calculation of an overall mean score for the dimension or construct. It is evident from Table 3 that all scales exhibit a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of more than 0.7, indicating internal consistency reliability for all scales concerned.

It is furthermore evident from Table 3 that the brand pleasure dimension realised the highest overall mean score of 3.67, followed by brand arousal (mean = 3.44). Brand dominance realised an overall mean score below the midpoint of the scale (mean = 1.81). It can therefore be concluded that respondents agree that their current cell phone brand is responsible for brand pleasure and brand arousal, but disagree that their current cell phone brand is dominant in their minds. Brand loyalty obtained an overall mean just below the midpoint of the scale (mean = 2.74). It can therefore be concluded that respondents do not exhibit strong levels of brand loyalty to the cell phone brand they currently own.

6.4 Construct validity

Validity is assessed to determine whether a scale measures what it is intended to measure (Pallant, 2010:7). For the scales measuring brand romance, Patwardhan and Balasubramanian (2011) indicated convergent as well as discriminant validity in their work. To measure brand loyalty, the researchers used a scale published by Keller (2001), which is frequently used to measure brand loyalty. With the aid of exploratory factor analyses, discriminant and construct validity of scales used in the study were assessed. In each case only one factor was extracted explaining between 66.254 per cent and 79.464 per cent of the variance in the data, with factor loadings between 0.706 and 0.927 being observed. The scales used to measure the underlying dimensions of brand romance and the brand loyalty construct have thus been deemed valid by the researchers for the purposes of this study.

6.5 Addressing the assumptions of multiple regression

Before a multiple regression analysis can be conducted, it is necessary for researchers to ensure that certain basic inherent assumptions are met (Pallant, 2010:150-151). The findings with respect to these assumptions are as follows:

- Tabachnnik and Fiddel (2007) (cited in Pallant, 2010:150) propose a sample size of 50 plus three times the number of independent variables equalling 74 as adequate to conduct a multiple regression. The study realised 371 respondents, well above the minimum of 74 respondents required when three independent variables are involved.

- Multicollinearity can be ruled out since none of the pairs of independent variables realised a correlation coefficient greater than 0.9 (Pallant, 2010:151), and none of the independent variables realised tolerance values below 0.1 or variance inflation factors above 10.0 (Pallant, 2010:158).

- No univariate or multivariate outliers were present in the data. Standardised residuals for independent variables did not exceed an absolute value of 3.3 and for combinations of independent variables, the Mahalanobis distances calculated were all below the critical value of 16.27, with Cooks distances less than 1 as prescribed by Tabachnnik and Fiddel (2007) (cited in Pallant, 2010:159).

- The normality of distribution, as well as homoscedasticity of variance assumptions have been met, since the data points in the Normal P-P Plot are in a fairly straight line and the Scatterplot of the standardised residuals is 'roughly rectangular, with most of the score concentrated in the centre' (Pallant, 2010:158).

Based upon the fact that these assumptions could be met, the researchers continued with a standard multiple regression analysis.

6.6 Multiple regression analysis results

The Pearson product moment correlations conducted for pairs of variables that include each of the three independent variables (brand pleasure, brand arousal and brand dominance) and the one dependent variable (brand loyalty) indicate significant linear relationships (p-value < 0.05) between all three pairs of variables. Each pair of variables exhibits correlation coefficients ranging between 0.550 and 0.678.

An overall correlation coefficient (R Square value) of 0.586 for the regression model is evident from Table 4. This indicates that the three independent variables (brand pleasure, brand arousal and brand dominance) explain 58.6 per cent of the variability in brand loyalty.

Table 5 presents the results of the ANOVA test. The significant p-value of less than 0.0005 indicates that at least one regression weight is not 0 and indicative of the fact that the regression model is indeed significant.

In Table 6 it can be seen that the p-value for the constant (p-value = 0.012) is significant (p-value < 0.05) and the null hypothesis that the constant is 0 can be rejected. It is furthermore evident from Table 6 that the three dimensions of brand romance are statistically significant predictors of brand loyalty. Brand arousal is the best predictor of brand loyally (beta-value = 0.378; p-value < 0.0005), followed by brand dominance (beta-value = 0.363; p-value < 0.0005) and finally brand pleasure (beta-value = 0.228; p-value < 0.0005).

The following findings regarding the hypotheses formulated for the study can therefore be made based upon the results of the standard multiple regression analysis:

- Ha1 that brand pleasure predicts consumers' brand loyalty towards their current cell phone brands should therefore not be rejected (beta-value = 0.228; p-value < 0.0005).

- Ha2 that brand arousal predicts consumers' brand loyalty towards their current cell phone brands should therefore not be rejected (beta-value = 0.378; p-value < 0.0005).

- Ha3 that brand dominance predicts consumers' brand loyally towards their current cell phone brands should therefore not be rejected (beta-value = 0.363; p-value < 0.0005).

The results of the standard multiple regression analysis used to test the hypotheses formulated for the study are visually portrayed in Figure 2.

7 Conclusion and managerial implications

For cell phone marketers to cultivate brand loyalty remains challenging, as consumers have numerous cell phone brands to choose from. Studies suggest that brand romance may predict brand loyalty better than brand attitude by enhancing attitudinal loyalty (Aurier & De Lanauze, 2011:823; Patwardhan & Bala-subramanian, 2011:304). This study therefore set out to determine extent to which the three underlying dimensions of brand romance predict brand loyally, namely pleasure, arousal and dominance among cell phone users.

Results of the study indicate that respondents do not have strong brand loyalty towards their cell phone brands. Respondents participating in this study could therefore possibly switch to another cell phone brand when renewing their contracts. Although this is the case, it is important for cell phone marketers to realise that most cell phone users stay with their particular cell phone brand for the duration of their contract. Therefore, cultivating brand loyalty before consumers engage in a contract or renew a contract is crucial for a cell phone brand's success.

In line with previous research on the different dimensions of brand romance (Kuikka & Laukkanen, 2012:531, 534; Patwardhan & Balasubramanian, 2011:304; Wang & Li, 2012: 149, 164, 170), the results from this study indicate that the three dimensions of brand romance, namely arousal, pleasure and dominance, are statistically significant predictors of brand loyalty. The results complement the present literature on brand romance as a viable construct for influencing brand loyalty (Burnham, Frels & Mahajan, 2003:120; Patwardhan & Balasubramanian, 2011:299). Although all three constructs of brand romance are statistically significant predictors of brand loyalty, brand arousal is the best predictor of brand loyalty, followed by dominance and pleasure respectively.

Since it is apparent from the descriptive results that respondents experience pleasure more than what they are aroused, or that the cell phone brand dominates their thoughts, getting consumers involved with the brand will help to increase arousal (Holbrook & Hirchman, 1982:133). To increase dominance, cell phone marketers must clearly differentiate themselves so that the brand will become part of consumers' identity (Burnham et al., 2003:119), instead of consumers viewing only the cell phone itself as part of their identity (Du Toit, 2011:40), thereby resulting in greater brand loyalty. Sarkar (2011:92) also suggests using romantic content in marketing communications to elicit romantic feelings for the brand.

Affect, like brand romance, is not easily changed, but cognition can be redirected through argumentation (Oliver, 1999:35). The possible influence of marketing stimuli aimed at attracting consumers to competitive brands will thus be weaker when brand romance is present, thereby resulting in more brand loyal consumers. For this reason, increasing brand romance could keep cell phone users brand loyal.

Finally, since the three dimensions of brand romance, namely pleasure, arousal and dominance, predict brand loyalty, cell phone marketers should attempt to increase consumers' brand romance to develop a brand loyal customer base.

8 Limitations and directions for future research

Brand romance is considered to be product-specific (Patwardhan & Balasubramanian, 2011:299) and what constitutes pleasure will differ across product categories (Holbrook & Hirchman, 1982:135). As only cell phone brands were investigated, findings cannot be generalised to other brands in other product categories.

This study followed a non-probability convenience sampling approach among cell phone users in the North West province of South Africa, implying that the results cannot be generalised to the entire study population. Also, similar to the study of Patwardhan and Balasubramanian (2011:299), this study did not consider the reasons why consumers engage in a romance with a brand in the first place, or how it can be imparted on consumers. Using quota sampling based upon age could have contributed to the representativeness of the sample and could have allowed for comparisons between different age groups.

A probability sample could be drawn by collaborating with established service providers such as Vodacom, Cell C and MTN. Through such collaboration, a longitudinal approach could be followed to measure consumers' brand romance and the extent to which it predicts brand loyalty over a period of time. Future research could include replicating the study in other product contexts to determine whether the three dimensions of brand romance, namely arousal, pleasure and dominance, predict brand loyalty.

Finally, the extent to which the dimensions of brand romance predict brand loyalty was determined in an instance where fairly low levels of brand loyalty transpired. It is therefore advisable to also investigate the extent to which the dimensions of brand romance predict brand loyalty in instances where higher levels of brand loyalty occur.

References

AFRICAN TELECOMS NEWS. 2012. African mobile factbook 2012. Available at: http://www.africantelecomsnews.com/ [accessed 2013-04-24]. [ Links ]

AKSOY, L., BUOYE, A., AKSOY, P., LARIVIËRE, B. & KEININGHAM, T.L. 2013. Cross-national investigation of the satisfaction and loyalty linkage for mobile telecommunications services across eight countries. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 27(1):74-82. [ Links ]

AURIER, P. & DE LANAUZE, G.S. 2011. Impacts of in-store manufacturer brand expression on perceived value, relationship quality and attitudinal loyalty. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 39(1):810-835. [ Links ]

BELAID, S. & BEHI, A.T. 2011. The role of attachment in building consumer-brand relationships: An empirical investigation in the utilitarian consumption context. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 20(1):37-47. [ Links ]

BLYCROFT. 2012. African mobile factbook 2012. Available at: http://www.africantelecomsnews.com/ [accessed 2013-04-24]. [ Links ]

BOHLMANN, L. 2011. Enter the cellular realm. The Daily Mail, 18(2):74-75, Dec. [ Links ]

BURNHAM, T.A., FRELS, J.K. & MAHAJAN, V. 2003. Consumer switching costs: A typology, antecedents and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(2):109-126. [ Links ]

CASTRO, K. & PITTA, D.A. 2012. Relationship development for services: an empirical test. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 21(2):126-131. [ Links ]

CHAUDHURI, A. & HOLBROOK, M.B. 2001. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2):81-93. [ Links ]

CHITTY, W., HUGHES, A. & D'ALESSANDRO, S. 2012. Services Marketing. Sydney, Australia: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

DAGGER, T.S. & DAVID, M.E. 2012. Uncovering the real effect of switching costs on the satisfaction-loyalty association: The critical role of involvement and relationship benefits. European Journal of Marketing, 46(4):447-468. [ Links ]

DAY, G.S. 1969. A two-dimensional concept of brand loyalty. Journal of Advertising Research, 9(3):29-35, Sept:69. [ Links ]

DELGADO-BALLESTER, E. & MUNUERA-ALEMÁN, J.L. 2001. Brand trust in the context of consumer loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 35(11/12):1238-1258. [ Links ]

DICK, A.S. & BASU, K. 1994. Customer loyalty: towards an integrated framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(2):99-113. [ Links ]

DLODLO, N. & CHENGADZAI, M. 2013. The relationship between technology acceptance and frequency of mobile commerce use amongst Generation Y consumers. Acta Commercii, 13(1):1-8. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v13i1.176 [accessed 2014-01-28]. [ Links ]

DRENGER, J., JAHN, S. & GAUS, H. 2012. Creating loyalty in collective hedonic services: The role of satisfaction and psychological sense of community. Schmalenbach Business Review (SBR), 64(1):59-76. [ Links ]

DU TOIT, J. 2011. Social mobile: 'Like this'. Marketing Mix, 29(7/8):40. [ Links ]

FOURNIER, S. 1998. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(4):343-373. [ Links ]

FRANZAK, F. & PITTA, D. 2011. Moving from service dominant to solution dominant brand innovation. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 20(5):394-401. [ Links ]

FRIPP, C. 2012. SA mobile usage study yields surprising results. Available at: http://www.itnewsafrica.com/2012/07/sa-mobile-usage-study-yields-surprising-results/ [accessed 2013-04-24]. [ Links ]

GUMMESSON, E. 2002. Relationship marketing in the new economy. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 1(1):37-57. [ Links ]

HAWKINS, D.I. & MOTHERSBAUGH, D.L. 2013. Consumer behaviour: Building marketing strategy. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

HESS, J., STORY, J. & DANES, J. 2011. A three-stage model of consumer relationship investment. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 20(1):14-26. [ Links ]

HOLBROOK, M.B. & HIRSCHMAN, E.C. 1982. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2):132-140, Sept. [ Links ]

HOLLIS, V. 2011. Mobile basics. Marketing Mix, 29(7/8):7. [ Links ]

HOYER, W.D., MACINNIS, D.J. & PIETERS, R. 2013. Consumer behavior (6th ed.) Mason, Ohio: SouthWestern Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

HUTTON, J. 2011. Mobile phones dominate in South Africa. Available at: http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/newswire/2011/mobile-phones-dominate-in-south-africa.html Date accessed: 24 April 2013. [ Links ]

HWANG, J. & KANDAMPULLY, J. 2012. The role of emotional aspects in younger consumer-brand relationships. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 21(2):98-108. [ Links ]

ISMAIL, A.R. & SPINELLI, G. 2012. Effects of brand love, personality and image on word of mouth. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 16(4):386-398. [ Links ]

JEON, S.M., HYUN, S.S. 2012. Examining the influence of casino attributes on baby boomers' satisfaction and loyalty in the casino industry. Current Issues in Tourism, 1-26. [ Links ]

KAUFMANN, H.R., LOUREIRO, S.M.C., BASILE, G. & VRONTIS, D. 2012. The increasing dynamics between consumers, social groups and brands. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 15(4):404-419. [ Links ]

KELLER, K.L. 2001. Building customer-based brand equity: A blueprint for creating strong brands. Marketing Sciences Institute, 1(107):1-31. [ Links ]

KIM, H. 2012. The dimensionality of fashion-brand experience. Aligning consumer-based brand equity approach. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 16(4):418-441. [ Links ]

KUIKKA, A. & LAUKKANEN, T. 2012. Brand loyalty and the role of hedonic value. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 21(7):529-537. [ Links ]

LAZAREVIC, V. 2012. Encouraging brand loyalty in fickle generation Y consumers. Young Consumers: Insight and Ideas for Responsible Marketers, 13(1):45-61. [ Links ]

LI, M., DONG, Z.Y. & CHEN, X. 2012. Factors influencing consumption experience of mobile commerce: A study from experiential view. Internet Research, 22(2):120-141. [ Links ]

LIU, F., LI, J., MIZERKI, D. & SOH, H. 2012. Self-congruity, brand attitude, and brand loyalty: A study on luxury brands. European Journal of Marketing, 46(7/8):922-937. [ Links ]

LONG-TOLBERT, S.J. & GAMMOH, B.S. 2012. In good and bad times: The interpersonal nature of brand love in service relationships. Journal of Service Marketing, 26(6):391-402. [ Links ]

MTN. 2013. Available at: http://www.mtn.co.za/AboutMTN/Pages/MTNSA.aspx [accessed 2013-04-24]. [ Links ]

MUGGE, R., SCHIFFERSTEIN, H.N.J. & SCHOORMANS, J.P.L. 2010. Product attachment and satisfaction: Understanding consumers' post-purchase behavior. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 27(3): 271-282. [ Links ]

NEWMAN, J.W. & WERBEL, R.A. 1973. Multivariate analysis of major household appliances. Journal of Marketing Research, 10(4):404-409. [ Links ]

OLIVER, R.L. 1999. Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63:33-44. [ Links ]

ORRILL, D. 2011. On a mobile mission. Marketing Mix, 29(7/8):48. [ Links ]

PALLANT, J. 2010. SPSS Survival manual (3rd ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

PAPISTA, E. & DIMITRIADIS, S. 2012. Exploring consumer-brand relationship quality and identification: Qualitative evidence from cosmetic brand. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 15(1): 33-56. [ Links ]

PATWARDHAN, H. & BALASUBRAMANIAN, S.K. 2011. Brand romance: A complementary approach to explain emotional attachment toward brands. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 20(4):297-308. [ Links ]

PERSAUD, A & AZHAR, I. 2012. Innovative mobile marketing via smartphones. Are consumers ready? Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 30(4):418-443. [ Links ]

PETRUZZELLIS, L. 2010. Mobile phone choice: technology versus marketing. The brand effect in the Italian market. European Journal of Marketing, 44(5):610-634. [ Links ]

ROUND, D.J.G. & ROPER, S. 2012. Exploring consumer brand name equity: Gaining insight through the investigation of response to name change. European Journal of Marketing, 46(7/8):938-951. [ Links ]

SAARF (South African Advertising Research Foundation). 2012. Cell phone trends. Available at: http://www.saarf.co.za/amps/cellphone.asp [accessed 2012-10-24]. [ Links ]

SARKAR, A. 2011. Romancing with the brand: a conceptual analysis of romantic consumer-brand relationship. Management and Marketing, 6(1):79-94. [ Links ]

SONG, Y., HUR, W.M. & KIM, M. 2012. Brand trust and affect in the luxury brand-customer relationship. Social Behavior and Personality, 40(2):331-338. [ Links ]

STATS SA. 2010. Post and telecommunications industry, 2010. Report No. 75-01-01. Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/ [accessed 2013-04-24]. [ Links ]

THORBJØRNSEN, H., SUPPHELLEN, M., NYSVEEN, H. & PEDERSEN, P.E. 2002. Building brand relationships online: A comparison of two interactive applications. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 16(3): 17-34, Summer. [ Links ]

TORRES-MORAGA, E., VÁSQUEZ-PARRAGA, A.Z. & ZAMORA-GONZÁLEZ, J. 2008. Customer satisfaction and loyalty: Start with the product, culminate with the brand. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 25(5):302-313. [ Links ]

TSAI, S.P. 2011. Fostering international brand loyalty through committed and attached relationships. International Business Review, 20(5):521-534. [ Links ]

TU, Y.T., WANG, C.M. & CHANG, H.C. 2012. Corporate brand image and customer satisfaction on loyalty: An empirical study of Starbucks Coffee in Taiwan. Journal of Social and Development Sciences, 3(1):24-32. [ Links ]

TUBBS, B. 2012. SA's cell phone market defined. Available at: http://www.itweb.co.za/index.php7option=com_content& view=article&id=57235 [accessed 2012-10-24]. [ Links ]

UNICEF. 2012. South African mobile generation: Study on South African young people on mobiles. http://www.unicef.org/southafrica/SAF_resources_ mobilegeneration.pdf [accessed 2013-04-24]. [ Links ]

VERMEULEN, J. 2012. SA Internet stats for 2011 revealed. Available at: http://mybroadband.co.za/news/internet/49533-sa-internet-stats-for-2011-revealed.html [accessed: 2013-04-24]. [ Links ]

VODACOM. 2013. Available at: http://www.vodacom.com/index.php [accessed 2013-04-24]. [ Links ]

WANG, W.T. & LI, H.M. 2012. Factors influencing mobile services adoption: A brand-equity perspective. Internet Research, 22(2):142-179. [ Links ]

WILSON, A., ZEITHAML, V.A., BITNER, M.J. & GREMLER, D.D. 2012. Services marketing: Integrating customer focus across the firm (2nd European ed.) Maidenhead, Berkshire: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

YE, L., BOSE, M. & PELTON, L. 2012. Dispelling the collective myth of Chinese consumers: A new generation of brand-conscious individualists. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(3):190-201. [ Links ]

Accepted: March 2014