Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versão On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.17 no.4 Pretoria Abr. 2014

The influence of the quality of working life on employee job satisfaction, job commitment and tenure intention in the SME sector in Zimbabwe

Richard ChinomonaI; Manilall DhurupII

ISchool of Economic and Business Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

IIFaculty of Management Sciences, Vaal University of Technology

ABSTRACT

A major reason for advocating for quality of work life has been the promise that it creates a win-win situation: improved employee satisfaction and welfare, hence increased productivity, longer employee tenure and consequently increased company profitability. Nevertheless, in the context of small to medium enterprises (SMEs), scant attention has been given to the empirical investigation into the influence of the quality of work life on employee tenure intention in Southern Africa. The purpose of this study is to fill this gap by examining the influence of SME employees' perceptions of the quality of work life on their tenure intention and the mediating role of job satisfaction and job commitment in this relationship as far as Zimbabwe is concerned. Five hypotheses were posited and sample data of 282 were collected from Harare, Zimbabwe's biggest city, to empirically test these hypotheses. The results of this study showed that, in the SME context, quality of work life positively and significantly influences employee job satisfaction, job commitment and consequently tenure intention. The managerial implications of the findings are discussed and limitations and future research directions are indicated.

Key words: quality of work life, job satisfaction, job commitment, tenure intention, small and medium enterprises

1 Introduction

It is not unusual nowadays to read in the newspapers or see on television that workers here or elsewhere are engaging on industrial action or are threatening to leave their jobs. The bottom line is that perhaps the workers feel they have been treated unfairly or inequitably remunerated at their workplace (Chinomona, Chinomona, & Joubert, 2013). Nevertheless, evidence indicates that it is more expensive for companies to hire a new worker than it is to retain a currently serving worker (Koys, 2001; Lau, 2000; Solomon, 1998). Besides, companies lose millions or even billions in currency or suffer damage to their reputation every time workers withdraw their labour or expose unfair treatment or unequal remuneration at their work place. As a result, both academics and labour experts have been pondering on and grappling with questions, such as, "What really ought to be done to motivate workers well enough to evade labor strikes and reduce turnover intention or turnover?" (Beauchamp & Bowie, 2004; Carroll & Buchholtz, 2006; Ferrell, Fraedrich & Ferrell, 2008). Could it be the quality of work-life that eventually influences job satisfaction and job commitment, and hence tenure intention? One field of research that has continually attracted the interest of organizational behavior researchers' and HR practitioners' is that of workers' tenure intention or their intention to stay on at work (Ryan, Schmit & Johnson, 1996; Koys, 2001; Ferrell et al., 2008; Allen, Shore & Griffeth, 2003). Both practitioners and academics have sought to find out what motivates employees to stay on in their jobs - tenure intention instead of turnover intention (Ryan et al., 1996; Lau, 2000; Dess, Lumpkin & Eisner, 2007).

There is a large body of research literature showing that, as companies incur high screening and training costs when hiring new workers, they often attempt to discourage employee turnover and inter-firm mobility among their valued workers by establishing long-term employment relationships and by attempting to enhance employees' utility (Theodossiou & Zangelidis, 2009). This, inter alia, is attained by providing workers with jobs that offer them a career path and rewards commensurate with tenure or simply quality of work life (Cummings & Worley, 2005; Dess et al., 2007). On one hand, previous empirical studies on employees' tenure intention focused mainly on antecedents such as job satisfaction, job involvement and organizational commitment (James, James & Ashe, 1990; Parker, Baltes, Young, Huff, Altmann & Lacost, 2003; Woodard, Cassill & Herr, 1994; Biswas, 2010). On the other hand, prior research on quality of work life focused largely on job-related outcomes or employee behavioral responses, such as organizational identification, job satisfaction, job involvement, job effort, job performance, intention to quit, organizational turnover or personal alienation (e.g. Biswas, 2010; Efraty & Sirgy, 1990; Koys, 2001; Efraty, Sirgy & Claiborne, 1991; Lewellyn & Wibker, 1990).

However, researchers have rarely investigated the important influence of employees' perceptions of the quality of work life (QWL) on their tenure intention, particularly in developing countries like those in Southern Africa. Even though empirical evidence from the developed countries like the USA and Europe exists, such evidence has very seldom been corroborated in an African research context. The current study might therefore serve to confirm or deny the related quality of work life outcomes in an African context, as these appear to have a different pattern of values and beliefs from those of the developed Western countries (Chinomona & Cheng, 2013). Thus, if the values supporting the workplace behaviors differ, it might be prudent to assume a priori that the meagre prior evidence from the developed parts of the world are no different, hence the need for this study. Furthermore, the small and medium enterprises (SMEs) sector is widely recognised as the engine of economic growth and employment generation in both developed and developing countries and yet research targeting this vital sector of the economy remains scarce (Chinomona & Pretorius, 2011; Chinomona, Lin, Wang & Cheng, 2010). Notably, prior research on quality of work life and tenure intention have focused mainly on large firms (e.g. Cummings & Worley, 2005; Dess et al., 2007) neglecting the SME sector. Given the unique characteristics of SMEs, for example, low resource endowment, perhaps too, the findings from the SME sector can be expected to differ from those of the large companies, hence the need for this study.

The present research is designed to fill the research gaps and to further validate the existing sparse evidence of the relationship between the quality of work life and tenure intention. This will be done by examining the influence of employee perceptions of the quality of work life and its influence on tenure intention in Zimbabwe's SME sector. Given that the research context is SMEs in Zimbabwe, an African country and a developing economy, it is an important contribution not only to the quality of work life and employees' tenure intention literature, but also to literature on organizational behavior within the small business context. Furthermore, the current study seeks to explore the influence of employee job satisfaction and job commitment on this relationship between quality of work life and tenure intention. Given the reported fundamental significance of job satisfaction and job commitment in the extant literature (e.g. Allen et al., 2003; Rhoades, Eisenberger & Armeli, 2001; Griffeth, Hom & Gaertner, 2000; Allen & Meyer, 1990) to HR practice, it is sensible to inquire about the extent to which they mediate the quality of the work life-tenure intention relationship in the SME sector. In addition, an effort is made to refer to Fairness theory (Folger & Cropanzano 2001), which was developed in the discipline of Psychology in order to explain antecedents of employees' tenure intention in the context of SMEs. This endeavor is considered to provide a strong theoretical grounding for the current research.

The rest of the article is organised as follows. A review of the literature, conceptual framework and hypotheses are presented. These are followed by a discussion on the methodology and the constructs and scales used, following which the analysis and conclusions are outlined. Finally, managerial implications, limitations and future research directions are given.

2 Literature review

2.1 Fairness theory

Fairness theory has previously been used in management studies to explain employee reactions to organizational authorities (Brockner, Fishman, Reb, Goldman, Speigel & Garden, 2007; Azar & Darvishi, 2011). According To Folger & Cropanzano 2001) and Cropanzano and Rupp (2003), Fairness theory is about injustice and justice is concerned with moral virtue. Fairness theory attempts to integrate the distinct components of justice into a global theory of fairness (Folger & Cropanzano, 2001). In Psychology studies, Fairness theory suggests that when individuals face negative situations, they make cognitive comparisons, known as "counterfactual thoughts" (Nicklin, Greenbaum, McNall, Folger & Williams, 2011). They compare what actually happened to what might have been (Elovainio, Bos, Linna, Kivimäki, Mursula & Pentti, 2005). Furthermore, individuals add their own thoughts, past experiences and personal modes of thinking to create complex interpretations (Azar & Darvishi, 2011). They often evaluate and react to the present circumstances in terms of what should, could and would (Duffy, Ganster, Shaw, Johnson & Pagon, 2006). These three facets (what should, could and would) of cognitive comparisons are the alternative scenarios, which are referred to as "counterfactuals" (Collie, Bradley & Sparks, 2002; Cropanzano, Chrobot-Mason, Rupp & Prehar, 2004; Duffy et al., 2006).

Relating Fairness theory to the current research, this study submits that, when SME employees evaluate the quality of work life at their workplace, they judge it against the should, could and would alternative scenarios. They ask themselves counterfactual questions, such as, "Would our quality of work life be better if remuneration increased, job security got better or the working conditions improved? Could the SME employer have increased the remuneration or improved the terms and working conditions? Should the SME employers, do something better? In a nutshell, the SME employees perceive the quality of work life to be unfair when they feel that they would have received better outcomes, while the SME employer could have acted differently and should have done so. On the other hand, if the SME employees perceive fairness in the three counterfactual questions, then their perceptions of the quality of work life in their company and eventually their tenure intentions should be expected to be influenced accordingly.

2.2 Quality of work life

The term quality of work life was first introduced in 1972 during the International Labor Relations Conference (Hain & Einstein, 1990). In recent years, the quality of work life (QWL) is increasingly being identified as a progressive indicator related to the function and sustainability of business organizations (Koonmee, Singhapakdi, Virakul & Lee, 2010). The rising complexity of the competitive business world and the cumbersome process of wage bargaining, wage negotiation deadlocks and bargaining, and the consequently disruptive nature of labor disputes has made many companies view their employees' quality of work life as an important strategic factor in protecting the company from unwanted disasters (e.g., Beauchamp & Bowie, 2004; Carroll & Buchholtz, 2006; Ferrell et al., 2008). In this study, the quality of work life is defined as the extent to which workers in an SME are able to satisfy important personal needs through their experiences at their workplace (Igbaria, Parasuraman & Badawy, 1994). Thus, an individual's quality of work life is defined by their affective reactions to both objective and experienced characteristics within the SME working environment. In the management discipline in general, prior research often links the quality of work life to job-related outcomes such as, inter alia, employee job effort, productivity, low absenteeism and organizational performance (e.g., Danna & Griffin, 1999; Cummings & Worley, 2005; Dess, et al., 2007; Leopold, 2005; Wheelan & Hunger, 2006; Yorks, 2005).

2.3 Employee Job Satisfaction

In the field of organizational behavior studies and human resources practice, there is increasing recognition of the fundamental significance of the concept of job satisfaction (Cranny, Smith & Stone, 1992). For instance, Yoon and Suh (2003) showed that satisfied employees are more likely to work harder and provide better services via organizational citizenship behaviors. The current study defines employee job satisfaction as a positive affective state resulting from the appraisal of all the aspects of a job by the employee (Silvestro & Cross, 2000). Such employee job satisfaction can be derived from economic outcomes or social interactions at the workplace. Overall, when the SME administration, service support, rewards and SME policies are perceived to be fair, the employee will be satisfied. Evidence mounting from previous studies indicates that job satisfaction is the most "robust" antecedent of employee commitment, service quality delivery, organizational citizenship behavior, and low employee turnover intention (Lovemore, 1998; Silvestro & Cross, 2000; Hartline & Ferrell, 1996).

2.4 Employee job commitment

Many researchers have found job commitment to be the key component of establishing and maintaining long-term relationships between companies and their employees (Meyer & Allen, 1997). Employee job commitment reflects the importance of a job in the company where the employee works and the intention to continue working in that job in the future (Rhoades et al., 2001; Allen et al., 2003). In this study, employee job commitment is defined as the employee's psychological attachment, internalised values of the goodness of job and enduring desire to maintain that valued job in the SME (c.f. Kankaanranta, 2013). In other words, it is the implicit or explicit pledge of relational continuity by the employee with the SME. Psychologists have identified affective, calculative or instrumental and normative as the main motivations of employee commitment (Meyer & Allen, 1997; Lee, Allen, Meyer & Rhee, 2001). Affective commitment means that employees want to stay in the job because they like their company, enjoy the working relationship and feel a sense of loyalty and belongingness. On the other hand, calculative commitment is the extent to which employees perceive the need to maintain a job with their company because of the significant anticipated switching costs or lack of alternatives. Normative commitment means that employees stay in the job because they feel they ought to (Cater & Zabker, 2009; Meyer & Allen, 1997). In empirical studies, employee job commitment is noted as being linked to job performance, firm productivity and citizenship behavior (Allen & Meyer 1990; Mathieu & Zajac 1990; Porter, Steers, Mowday & Boulian, 1974; Somers 1995).

2.5 Employee tenure intention

The questions that challenge academics and practitioners alike are: "Why do people leave their jobs?" and "Why do they stay in their jobs?" Over the years, researchers have developed partial answers to these questions (Hom & Griffeth, 1995; Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski & Erez, 2001). Perhaps, given alternatives, people stay if they are satisfied with their jobs and are committed to their organizations, and leave if they are not. However, empirical evidence indicates that work attitudes have a relatively weak influence (p.v. = 0.10) on employee tenure or turnover intention (Griffeth et al., 2000). Other factors besides job satisfaction, organizational commitment and job alternatives are therefore important in understanding tenure intention (Maertz & Campion, 1998). Mitchell, et al. (2001) Identified job embeddedness and job fit are other important factors that influence tenure intention. The quality of work life is identified in this research as one important antecedent of employee tenure intention. Besides, meta-analytical findings by, for instance, Tett and Meyer (1993), Griffeth, Hom and Gaertner (2000) and Bal, De Lange, Jansen and Van Der Velde (2008) noted job satisfaction, commitment, job attitude and trust as some of the predictors of tenure intention or turnover intention. Drawing from the extant literature, the current study defines tenure intention as the future number of years the employee is willing to stay at the SME (c.f. Trimble, 2006).

2.6 Conceptual model and research hypothesis

Fairness theory (Folger & Cropanzano, 2001; Cropanzano & Rupp, 2003) provides a theoretical grounding for this research and, based on the reviewed research constructs literature, a research model is conceptualized. Figure 1 below denotes the conceptualized research model for the current study. In this research model, quality of work life is regarded as the predictor of an employee's job satisfaction, employee job commitment and employee tenure intention in the SME context. Employees' job satisfaction and job commitment are also predicted to mediate the relationship between employees' perceptions of quality of work life and their tenure intention. Accordingly, the SME employees' perceptions of the quality of work life at their workplace are expected to directly or indirectly influence their tenure intention via job satisfaction and job commitment (Koonmee et al, 2010). The hypothesized linkages between these research constructs are provided, following the conceptual model in Figure 1.

2.7 Quality of work life and employee job satisfaction, commitment and tenure intention

Why is quality of work life (QWL) important? It could be argued that a better quality of work life makes employees satisfied with their job at their workplace and that contentment trickles down to their home and family life. There is some evidence showing that satisfied employees are happy employees; happy employees are dedicated and loyal; happy employees are therefore productive and tend to stay longer with a company (Sirgy, Efraty, Siegel & Dong-Jin, 2001). The quality of work life is depicted by favorable conditions and environments of a workplace that support and promote employee job satisfaction by providing employees with better reward systems, job security and growth opportunities (Sirgy et al., 2001). Cascio (1998) argued that employees who work in organizations where QWL exists, like their organizations and feel that their work fulfills their needs. Eventually, the fulfillment of employees' needs will trigger their satisfaction with the job, commitment to the job and the desire for long tenure at their workplace. According to Maslow (1954), these needs encompass specifically health and safely needs (protection from ill health and injury at work and outside of work, and enhancement of good health); economic and family needs (pay, job security, and other family needs); social needs (collegiality at work and leisure time off work); esteem needs (recognition and appre- ciation of work in and outside the organization); actualization needs (realization of one's potential within the organization and as a professional); knowledge needs (learning to enhance job and professional skills); and aesthetic needs (creativity at work as well as personal creativity and general aesthetics). Similarly, in the context of this study, when SME employees perceive themselves to have attained quality in work life, they are likely to view their SME as fair and as caring for their needs. Eventually, the perceived fulfillment of their needs will in all likelihood lead to the SME employees' satisfaction with their job, and commitment to it. They will also be motivated to seek longer tenure with their respective SMEs. Evidence from prior studies has supported a positive linkage between the quality of work life and employee job satisfaction, job commitment and tenure intention (Heskett, Jones, Loveman, Sasser & Schlesinger, 1994; Lau, 2000; Seashore, 1975). According to Fairness theory, empirical evidence and the foregoing discussion, the following hypotheses can be postulated:

H1: There is a positive relationship between the quality of work life and employees' job satisfaction in the SME sector.

H2: There is a positive relationship between the quality of work life and employees' job commitment in the SME sector.

H3: There is a positive relationship between the quality of work life and employees' tenure intention in the SME sector.

2.8 Employee job satisfaction, job commitment and tenure intention

Employee job satisfaction and job commitment are essential to the implementation of higher performance work systems that contribute to a company's financial performance (Osterman, 1995; Sirgy et al., 2001). However, financial performance cannot be sustained unless the non-financial underpinnings of employee job satisfaction, job commitment and hence productivity improve (Sirgy et al., 2001). In this study, it is expected that when SME employees derive economic or socio-psychological satisfaction from their job, they will not contemplate leaving the SME, but will be motivated to stay longer. Economic satisfaction occurs, for instance, when the SME employees are content with the SME reward system. According to Herzberg's theory on hygiene factors, social or psychological satisfaction occurs when the employees are pleased with, for example, the general working conditions at their workplace. The current study also submits that when SME employees are loyal and committed to their job, they want to stay longer with the SME. This commitment could be affective, instrumental or normative. When employees are emotionally attached to a job, they are regarded as having affective commitment. However, when they are committed to the job because of, for instance, job switching costs or attractive rewards offered by the current job then they have normative or instrumental commitment. Accor-dingly, the current study posits that when SME employees are satisfied and become committed to their jobs, they are likely to view their workplace as their second home. Consequently, the perception of attachment would act as social glue that motivates them to want long tenure with their SME. Previous studies have also found a positive relationship between employee job satisfaction, job commitment and tenure intention (Shore & Martin, 1989; Hansen, Sandvik & Selnes, 2003). Therefore, drawing from the Fairness theory, the empirical evidence and the above discussion, the current study posits the following hypotheses:

H4: There is a positive relationship between employees' job satisfaction and their tenure intention in the SME sector.

H5: There is a positive relationship between employees' job commitment and their tenure intention in the SME sector.

3 Research methodology

3.1 Sample and data collection

The data used for this study were collected from SME employees in Harare, the biggest city in Zimbabwe. The sample included employees from both the manufacturing and service sectors. University of Zimbabwe students were recruited to assist with the distribution and collection of the questionnaires after permission had been sought from the SME owners or managers. The questionnaires clearly stated that the anonymity of the participants would be guaranteed and that the study was purely for academic purposes. Of the 390 questionnaires distributed, 320 returned questionnaires were usable, yielding a response rate of 82 per cent.

3.2 Measurement instrument development

Research scales were operationalized mainly on the basis of previous work. Proper modifications were made in order for them to fit the current research context and purpose. For instance, where the original adapted measurement item used the term 'organization' the current study substituted this with the term 'company'. A six-item scale adapted from Donaldson, Sussman, Dent, Severson and Stoddard (1999) was used to measure "employees' perceptions of quality of work life". "Employees' job satisfaction" used a five-item scale measure adopted from Kim, Leong and Lee (2005), while "employees' job commitment" used a five-item scale from Weng, McElroy, Morrow and Liu (2010). Finally, a three-item scale to measure "employees' tenure intention" was adopted from Hansen, Sandvik and Selnes (2003). All the measure-ment items were measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale that was anchored by 1= strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree to express the degree of agreement. Individual scale items are listed in the Appendix.

4 Data analysis

4.1 Respondent profile

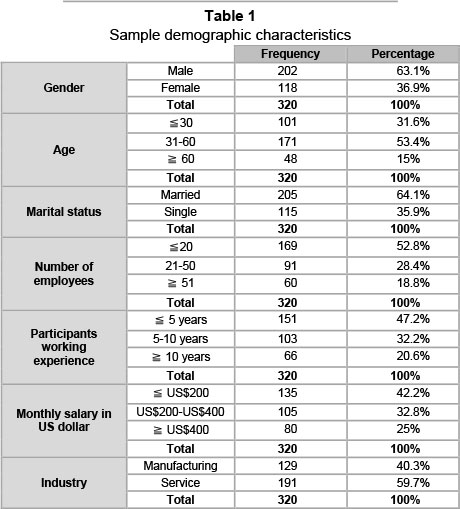

SME employees who answered the questionnaires belonged to both the service and the manufacturing sectors in Harare. The descriptive statistics presented in Table 1 show the gender, age, marital status, and the number of employees in the company, the respondent's working experience and monthly salary, as well as the type of industry.

Table I shows that males dominate the SME sector and constitute 63.1 per cent of the workforce. The most active age group in the participating SMEs is the one between 31-60 years which constitutes 53.4 per cent of the total workforce. Employees who are single occupy 64.1 per cent and the remainder are married. The profile indicates that more than half of the participating SMEs employed 20 or fewer workers. Participants with less than 5 years' work experience constituted 47.2 per cent. The majority of the participants, that is, 42.2 per cent, earned below US$200 a month. The study also indicated that the majority of the participants belonged to the service sector, which occupied 59.7 per cent, while the manufacturing sector occupied the remainder.

5 Results

5.1 Assessing measurement model fit

The researcher followed the two-step approach advocated by Anderson and Gerbing (1988), that is, to estimate a measurement model prior to examining structural model relationships. The four research constructs were modeled as four correlated first-order factors corresponding to a six-item quality of work life factor, a five-item employee job satisfaction factor, a six-item employee job commitment factor, and a three-item employee tenure intention factor. LISREL 8.8 was used, with covariance as input, to estimate the model.

The results for the measurement model are presented in Table 2. The goodness-of-fit index (GFI) and the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) values were .90 and .87 respectively, which indicates marginal fit. Since Hoyle and Panter (1995) suggested that GFI and AGFI might suffer from inconsistencies due to sampling characteristics, this study reports four other fit indices that have been viewed as robust to sampling characteristics (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson & Tatham, 2006), that is: the comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), Normed fit index (NFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Values in the range equal to or above .90 have been noted as designating adequate fit for CFI, IFI, NFI indices and less than 0.080 for RMSEA index (Bryne, 2001; Dilalla, 2000; Hair et al., 2006). Also, as indicated in Table 2, the fit for all these indices was adequate.

Evidence of internal consistency is provided by composite reliability and coefficient alpha. Composite reliability is a LISREL-generated estimate of internal consistency analogous to coefficient alpha (Fornell & Larcker 1981). The results presented in Table 2 indicate that, these two estimates ranged from .77 to .88. Table 2 also include the average variance extracted estimates, which assess the amount of variance captured by a construct's measure relative to measurement error, and the correlations among the latent constructs in the model. Average variance extracted estimates of .50 or higher indicate validity for a construct's measure (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). All the AVE estimates achieved this criterion.

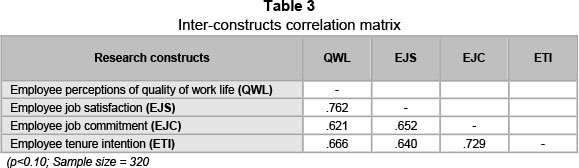

Furthermore, all the item-loadings for each factor were significant (p<0.10) and ranged from .67 to .78 for quality of work life (QWL), .61 to .80 for employee job satisfaction (EJS), .71 to .79 for employee job commitment (EJC), and .71 to .76 for employee tenure intention (ETI). Therefore, all item-to-total values for all research constructs were above the recommended .5 (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988), indicating acceptable individual item convergent validity as more than 50 percent of each item's variance was shared with its respective construct. Two tests were performed to check discriminant validity among factors. First, the researcher checked whether the square of the parameter estimate between two constructs was less than the average variance extracted estimates of the two constructs (Fomell & Larcker 1981). Second, as suggested by Hulland (1999), the researcher checked whether the correlations between the research constructs were less than .8. Although the correlation values can be regarded as being generally moderate to high, they are marginally acceptable (Hulland, 1999). Table 3 presents the research constructs correlation matrix. As such, all these criteria were adequately met across all the possible pairs of constructs.

5.2 Structural model results

Since acceptable CFA measurement model fit was obtained, the study proceeded to the next stage of checking the structural model fit and hypothesis testing. Table 4 presents the results for the structural model depicted in Figure 1. The overall fit of the structural model was adequate and the recommended statistics for the overall structural equation model fit indices were χ2/df =2.9612; GFI=0.93; CFI=0.98; IFI=0.98; NFI=0.97; RMR=0.49 and RMSEA= 0.080. As shown in Table 4, the completely standardized path estimates indicate significant relationships among the constructs at p<0.10. These results provided support for the entire proposed five research hypothesis. The path coefficients for H1, H2, H3, H4 and H5 are β=0.84, β=0.24, β=0.67, β=0.31 and β=0.62 respectively.

Specifically, the first hypothesis postulated was that of the relationship between quality of work life and employee job satisfaction. Consistent with hypothesis one (H1), results indicate that the greater the perceived quality of work life, the higher will be the levels of employee job satisfaction. The second posited hypothesis was that of a positive relationship between quality of work life and employee job commitment. Also in support of hypothesis two (H2), the results indicate that higher levels of perceived quality of work life are positively associated with higher levels of employee job commitment. The third proposed hypothesis was that there was a positive relationship between the perceived quality of work life and employee tenure intention. The path coefficient of quality of work life for employee tenure intention is positive and significant. This implies that hypothesis three (H3) is consistent with the current study prediction and is supported. Thus, higher levels of perceived quality of work life are associated with higher levels of the SME employees' tenure intention. The fourth posited hypothesis was that there was a relationship between the SME employees' job satisfaction and their tenure intention. Also in support of hypothesis four (H4), the results indicate that the greater the levels of the SME employees' job satisfaction, the stronger will be their tenure intention. The last postulated hypothesis was the relationship between the SME employees' job commitment and their tenure intention. The empirical results of the current study are in line with proposed hypothesis five (H5) and support the reasoning that the higher the levels of the SME employees' job commitment the stronger their tenure intention.

6 Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of the current research was to examine the influence of SME employees' perception of quality of work life on their job satisfaction, job commitment and tenure intention. Fairness theory was used to provide a theoretical grounding for the conceptualised framework. In particular, five hypotheses were posited. To test the hypotheses, data were collected from SME employees in Zimbabwe. Drawing from the empirical results of this study, all the postulated research hypotheses were supported in a significant way.

It is important to note that the SME employees' perceptions of quality of work life strongly influenced their job satisfaction (0.84) more than it did their job commitment (0.24). This result is surprising. As strong bonds and ties were expected to exist between Zimbabwean SME employers and their employees, who are likely to be relatives or acquaintances (Chinomona et al., 2010), it was anticipated that the influence of quality of work life would be much stronger on job commitment than on job satisfaction. Perhaps this could be explained by the fact that, since the SME employees might find themselves obliged to be committed to their jobs by virtue of the assumed existing social ties and bonds, the improved quality of work life becomes more of a motivator to their job satisfaction. However, it is paradoxical that the SME employees' job commitment has a more robust influence on their tenure intention (0.67) than does their job satisfaction (0.31) and their perceptions of the quality of work life (0.62) on this. Perhaps, too, this reinforces the assumed possible strong influence of social ties and bonds on SME employees' job commitment, hence their tenure intention.

7 Implications of the study

The current research is the first to study these relationships using data collected from SME employees in Zimbabwe. Because of the rapidly growing importance of the SME sector, particularly employment generation and the economic growth of Zimbabwe, these findings provide fruitful implications for both practitioners and academicians. On the academic side, this study makes a significant contribution to the organizational behavior and human resources management literature by systematically examining the influence of quality of work life on employees' job satisfaction, job commitment and tenure intention in the SME context. Overall, the current study findings provide tentative support for the proposition that the quality of work life should be recognised as a significant antecedent for employees' job satisfaction, job commitment and tenure intention in the SME context. In addition, this study made a successful attempt to apply a theory borrowed from a disciplinary range, including Psychology, Fairness theory and HR-related matters in the SME context. Based on this, it is therefore submitted that Fairness theory can be extended to explain organizational behavior and HR management issues in small business settings. Overall, this study is expected to further expand the horizons of our comprehension of organizational behavior and HR issues in an important but often much neglected research context of the SME sector in developing countries in Southern Africa.

From the practitioners' perspective, the important influential role of the quality of work life on employees' job satisfaction, job commitment and tenure intention is highlighted. It is therefore submitted that SME owners and their managers could benefit from these findings. Given that empirical evidence has consistently shown that it is more expensive to hire a new employee than to retain one who is already there, it is imperative that SME owners and their managers promote their employees' quality of work life in order to keep them satisfied and committed to their jobs, which, after all, explains their willingness to stay longer in the company. Further, most of these SME employees might possess certain expertise or special skills acquired during their current tenure. If continuously used effectively by the SME owners over a protracted period of time, it might give the company the edge over their competitors and consequently help establish the SME's long-term viability and profitability. In order to further improve the quality of work life, the SME owners or managers should always consider matters like increasing their employees' remuneration in line with the company's performance and the employees' work input (employee equity). They should also be mindful of improving the working conditions, especially employees' safety at work which, in certain instances happens to be below the government stipulated safety standards (Chinomona et al., 2010). Perhaps, too, improving the working relations, particularly between the SME owners or managers and the employees by adopting proper codes of conduct and business ethics might help. A cursory observation indicates that many SMEs in Zimbabwe appear to be lacking proper codes of business conduct in comparison with large firms. In brief, this study submits that if SME owners and their managers can successfully turn their companies into supportive organizations that ensure a better quality of work life, their employees' job satisfaction and job commitment will be enhanced, and hence their tenure intention. Eventually, this could create a win-win situation whereby the employees are motivated to be more productive and the SMEs' profitability is increased in the process. Finally, it is also interesting to note that the measures applied very well to the Zimbabwean context, judging by the identified psychometric properties (Chinomona et al., 2010).

7.1 Limitations and future research

Although this study makes significant contributions to both academia and practice, it was limited in some ways, so some future research directions are suggested. First, self-ratings of the study variables were collected from SME employees. The results would be more informative if data from both sides of the dyad were compared. Future studies may be conducted by using paired data from both the SME employers' and employees' points of view. Second, the current study was limited to SMEs in Zimbabwe. Subsequent research should consider replicating this study in other developing countries for the comparison of results. Future studies could also extend the current study's conceptual framework by considering the effects of a larger set of variables. For instance, the influence of employees' perceptions of the quality of work life in workplace spirituality and citizenship behaviors could be investigated. Since this study did not check the common method bias, it is recommended that future researchers attend to this. This study used the 'Fairness theory' to ground it, but another avenue of future research is to consider the 'Theory of Planned Behaviour'. In addition, this would contribute extensively to new knowledge to the existing body of organizational behavior and management literature on small business in developing countries which are neglected in academic research contexts.

References

ALLEN, D.G., SHORE, L.M. & GRIFFETH, R.W. 2003. The role of perceived organizational support and supportive human resource practices in the turnover process. Journal of Management, 29(1):99-118. [ Links ]

ALLEN, N.J. & MEYER, J.P. 1990. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63:1-18. [ Links ]

ANDERSON, J.C. & GERBING, D.W. 1988. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103:411-423. [ Links ]

AZAR, A. & DARVISHI, Z.A. 2011. Development and validation of a measure of justice perception in the frame of Fairness theory - Fuzzy approach. Expert Systems with Applications, 38:7364-7372. [ Links ]

BAL, B.M., DE LANGE, A.H., JANSEN, P.G.W. & VAN DER VELDE, M.E.G. 2008. Psychological contract breach and job attitudes: A meta-analysis of age as a moderator. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72: 143-158. [ Links ]

BEAUCHAMP, T.L. & BOWIE, N.E. 2004. Ethical theory and business. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

BISWAS, S. 2010. Relationship between psychological climate and turnover intentions and its impact on organizational effectiveness: A study in Indian organizations. IIMB Management Review, 22:102-110. [ Links ]

BROCKNER, J., FISHMAN, A.Y., REB, J., GOLDMAN, B., SPIEGEL, S. & GARDEN, C. 2007. Procedural fairness, outcome favorability, and judgments of an authority's responsibility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92:1657-1671. [ Links ]

BYRNE, B.M. 2001. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. [ Links ]

CARROLL, A.B. & BUCHHOLTZ, A.K. 2006. Business and society. Mason, OH: South-Western Thomson. [ Links ]

CASCIO, W.F. 1998. Managing human resources: Productivity, quality of work life, profits. Boston, MA: Irwin McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

CATER, B. & ZABKAR, V. 2009. Antecedents and consequences of commitment in marketing research services: The client's perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 38(7):785-797. [ Links ]

CHINOMONA, R. & CHENG, J. 2013. Distribution channel relational cohesion exchange model: A small-to-medium enterprise manufacturer's perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(2):256-275. [ Links ]

CHINOMONA, R., LIN, J., WANG, M. & CHENG, J. 2010. Soft power and desirable relationship outcomes in Zimbabwe distribution channels. African Journal of Business, 11(2):20-55. [ Links ]

CHINOMONA, R. & PRETORIUS, M. 2011. SME manufacturers' cooperation and dependence on major dealers' expert power in distribution channels. South African Journal of Economics and Management Sciences, 12(2):170-186. [ Links ]

CHINOMONA, R., CHINOMONA, E. & JOUBERT, P. 2013. Perceptions of equity and organizational commitment in the Zimbabwean hospitality industry: Implications for HR managers or employers. South African Journal of Labour Relations, 37(2). [ Links ]

COLLIE, T., BRADLEY, G. & SPARKS, B.A. 2002. Fair process revisited: Differential effects of interactional and procedural justice in the presence of social comparison information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(6):545-555. [ Links ]

CRANNY, C.J., SMITH, P.C. & STONE, E.F. 1992. Job satisfaction: Advances in research and applications. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

CROPANZANO, R., CHROBOT-MASON, D., RUPP, D.E. & PREHAR, C.A. 2004. Accountability for corporate injustice. Human Resource Management Review, 14:107-133. [ Links ]

CROPANZANO, R, & RUPP, D.E. 2003. The relationship of emotional exhaustion to job performance ratings and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88:150-160. [ Links ]

CUMMINGS, T.G. & WORLEY, C.G. 2005. Organizational development and change. Cincinnati, OH: Thomson South-Western College Publishing. [ Links ]

DUFFY, M.K., GANSTER, D.C., SHAW, J.D., JOHNSON, J.L. & PAGON, M. 2006. The social context of undermining behavior at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process, 101:105-121. [ Links ]

DANNA, K. & GRIFFIN, R.W. 1999. Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Management, 25(3):357-384. [ Links ]

DESS, G.G., LUMPKIN, G.T. & EISNER, A.B. 2007. Strategic management. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Irwin. [ Links ]

DILALLA, L.F. 2000. Structural equation modeling: uses and issues. In: Tinsley, H.E.A., Brown, S.D. (eds.) Handbook of Applied Multivariate Statistics and Mathematical Modeling. Academic Press, New York, NY:439-464. [ Links ]

DONALDSON, S.I., SUSSMAN, S., DENT, C.W., SEVERSON, H.H. & STODDARD, J.L. 1999. Health behavior, quality of work life, and organizational effectiveness in the lumber industry. Health Education & Behavior, 26(4):579-591. [ Links ]

EFRATY, D. & SIRGY, M.J. 1990. The effects of quality of working life (QWL) on employee behavioral responses. Social Indicators Research, 22(1):31-47. [ Links ]

EFRATY, D., SIRGY, M.J. & CLAIBORNE, C.B. 1991. The effects of personal alienation on organizational identification: A quality-of-work life model. Journal of Business and Psychology, 6:57-78. [ Links ]

ELOVAINIO, M., BOS, K., LINNA, A., KIVIMÁKI, M., MURSULA, L. & PENTTI, J. 2005. Combined effects of uncertainty and organizational justice on employee health: Testing the uncertainty management model of fairness judgments among Finnish public sector employees. Social Science & Medicine, 61(12): 2501-2512. [ Links ]

FERRELL, O.C., FRAEDRICH, J. & FERRELL, L. 2008. Business ethics: Ethical decision making and cases. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

FOLGER, R. & CROPANZANO, R. 2001. Fairness theory: Justice as accountability. In Greenberg, J. & Cropanzano, R. (eds.) Advances in organizational justice, 1:1-55. New York: Information Age Publishers. [ Links ]

FORNELL, C. & LARCKER, D.F. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1):39-50. [ Links ]

GRIFFETH, R.W., HOM, P.W. & GAERTNER, S. 2000. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26:463-488. [ Links ]

HAIR, J.R., J.F., BLACK, W.C., BABIN, B.J., ANDERSON, R.E., TATHAM, R.L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis ( 6th ed.) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, [ Links ]

HANSEN, H., SANDVIK, K. & SELNES, F. 2003. Direct and indirect effects of commitment to a service employee on the intention to stay. Journal of Service Research, 5(4):356-368. [ Links ]

HAIN, C.C. & EINSTEIN, W.O. 1990. Quality of work life (QWL): What can unions do? S.A.M. Advanced Management Journal, 55(2):17-22. [ Links ]

HARTLINE, M.D. & FERRELL, O.C. 1996. The management of customer-contact service employees: An empirical investigation. Journal of Marketing, 60:52-70. [ Links ]

HESKETT, J.L., JONES, T.O., LOVEMAN, G.W., SASSER, W.E. J.R. & SCHLESINGER, L.A. 1994.Putting the service-profit chain to work. Harvard Business Review, March-April:164-74. [ Links ]

HOM, P.W. & GRIFFETH, R.W. 1995. Employee turnover. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western College Publishing. [ Links ]

HOYLE, R.H. & PANTER, A.T. 1995. Writing about structural equation models, in Structural Equation Modeling Concepts, Issues, and Applications, Hoyle, R.H. (ed.) Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications: 158-76. [ Links ]

HULLAND, J. 1999. Use of partial least squares (pls) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20(2):195-204. [ Links ]

IGBARIA, M., PARASURAMAN, S. & BADAWY, M.K. 1994. Work experiences, job involvement, and quality of work life among information systems personnel. MIS Quarterly, 18(2): 175-201. [ Links ]

JAMES, L.R., JAMES, L.A. & ASHE, D.K. 1990. The meaning of organizations: The role of cognition and values. In Schneider, B. (ed.) Organizational culture and climate (pp. 4084). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. [ Links ]

KANKAANRANTA, T. 2013. Factors influencing economic crime investigators' job commitment, Police Practice and Research, 14(1):53-65. [ Links ]

KIM, W.G., LEONG, J.K. & LEE, Y.K. 2005. Effect of service orientation on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intention of leaving in a casual dining chain restaurant. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 24(2):171-193. [ Links ]

KOONMEE, K., SINGHAPAKDI, A., VIRAKUL, B. & LEE, D.J. 2010. Ethics institutionalisation, quality of work life, and employee job-related outcomes: A survey of human resource managers in Thailand. Journal of Business Research, 63:20-26. [ Links ]

KOYS, D.J. 2001. The effects of employee satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior and turnover on organizational effectiveness: A unit-level, longitudinal study. Personnel Psychology, 54:101-114. [ Links ]

LAU, R.S.M. 2000. Quality of work life and performance: An ad hoc investigation of two key elements in the service profit chain model. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 11(5):422-437. [ Links ]

LEE, K., ALLEN, N., MEYER, J.P. & RHEE, K-Y. 2001. The three-component model of organizational commitment: An application to South Korea, Applied Psychology, 50(4):596-614. [ Links ]

LEWELLYN, P.A. & WIBKER, E.A. 1990. Significance of quality of life on turnover intentions of certified public accountants, in Meadow, H.L. and Sirgy, M.J. (eds.) Quality-of-Life Studies in Marketing and Management (International Society for Quality-of-Life Studies, Blacksburg, Virginia):182-193. [ Links ]

LEOPOLD, J. 2005. Employee participation, involvement, and communications. In: Leopold, J., Harris, L., Watson, T. (eds.) The strategic managing of human resource. Essex, England: Prentice-Hall Pearson Education:434-60. [ Links ]

LOVEMORE, G. 1998. Employee satisfaction, customer loyalty, and financial performance: An empirical examination of the service profit chain in retail banking. Journal of Service Research, 1(1):18-31. [ Links ]

MAERTZ, C.P. & CAMPION, M.A. 1998. 25 years of voluntary turnover research: A review and critique. In C.L. Cooper & I.T. Robertson, International review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 13:49-81. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

MASLOW, A. 1954. Motivation and personality. New York: HarperCollins. [ Links ]

MATHIEU, J.E. & ZAJAC, D. 1990. A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108:171-194. [ Links ]

MEYER, J.P. & ALLEN, N.J. 1997. Commitment in the workplace. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

MITCHELL, T.R., HOLTOM, B.H., LEE, T.W., SABLYNSKI, C.J. & EREZ, M. 2001. Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. The Academy of Management Journal, 44(6): 1102-1121. [ Links ]

NICKLIN, J.M., GREENBAUM, R., MCNALL, L.A., FOLGER, R. & WILLIAMS, K.J. 2011. The importance of contextual variables when judging fairness: An examination of counterfactual thoughts and fairness theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 114:127-141. [ Links ]

OSTERMAN, P. 1995. Work/family programs and the employment relationship. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(4):681-700. [ Links ]

PARKER, C.P., BALTES, B.B., YOUNG, S.A., HUFF, J.W., ALTMANN, R.A. & LACOST, H.A. 2003. Relationship between psychological climate perceptions and work outcomes: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24:389-416. [ Links ]

PORTER, L.W., STEERS, R.M., MOWDAY, R.T. & BOULIAN, P.V. 1974. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59:603-609. [ Links ]

RHOADES, L., EISENBERGER, R. & ARMELI, S. 2001. Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86:825-836. [ Links ]

RYAN, A.M., SCHMIT, M.J. & JOHNSON, R. 1996. Attitudes and effectiveness: Examining relations at an organizational level. Personnel Psychology, 49:853-882. [ Links ]

SEASHORE, S.E. 1975. Defining and measuring the quality of working life. In Davis, L.E. & Cherns, A.B. (eds.) The Quality of Working Life (Free Press, New York): 105-118. [ Links ]

SHORE, L.M. & MARTIN, H.J. 1989. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment in relation to work performance and turnover intentions. Human Relations, 42(7):625-638. [ Links ]

SIRGY, M.J., EFRATY, D., SIEGEL, P. & DONG-JIN, L. 2001. A new measure of quality of work life (QWL) based on need satisfaction and spillover theories. Social Indicators Research, 55:241-302. [ Links ]

SILVESTRO, R. & CROSS, S. 2000. Applying the service profit chain in a retail environment: Challenging the "satisfaction mirror". International Journal of Service Industry Management, 11(3):244-268. [ Links ]

SOLOMON, J. 1998. Companies try measuring cost savings from new types of corporate benefits. The Wall Street Journal, 29:B1. [ Links ]

SOMERS, M.J. 1995. Organizational commitment, turnover and absenteeism: An examination of direct and interaction effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16:49-58. [ Links ]

TETT, R.P. & MEYER, J.P. 1993. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology, 46:259-293. [ Links ]

THEODOSSIOU, I. & ZANGELIDIS, A. 2009. Career prospects and tenure-job satisfaction profiles: Evidence from panel data. Journal of Socio-Economics, 38(4):648-657. [ Links ]

TRIMBLE, D.E. 2006. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intention of missionaries. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 34(4):349-360. [ Links ]

WENG, Q., McELROY, J.C., MORROW, P.C. & LIU, R. 2010. The relationship between career growth and organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(3):391-400. [ Links ]

WHEELAN, T.L. & HUNGER, J.D. 2006. Strategic management and business policy. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Pearson Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

WOODARD, G., CASSILL, N. & HERR, D. 1994. The relationship between psychological climate and work motivation in a retail environment. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

YOON, M.H. & SUH, J. 2003. Organizational citizenship behaviors and service quality as external effectiveness of contact employees. Journal of Business Research, 56(8):597-611. [ Links ]

YORKS, L. 2005. Strategic human resource development. Mason, OH: South-Western Thomson. [ Links ]

Accepted: June 2013

Appendix:

Research construct measurement

Quality of work life

QWL1: My company provides a good working environment for its employees.

QWL2: I am happy at my company.

QWL3: My work is not stressful.

QWL4: I get along well with my coworkers.

QWL5: I have good supervision at work.

QWL6: My job security is good.

Employee job satisfaction

ES1: I consider my job pleasant.

ES2: I feel fairly-well satisfied with my present job.

ES3: I definitely like my job.

ES4: My job is pretty interesting.

ES5: I find real enjoyment in my job.

Employee job commitment

EC1: I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this job.

EC2: I really feel as if the problems associated with this job are my problems.

EC3: Right now, staying with my job is a matter of necessity as much as desire.

EC4: It would be very hard for me to leave my job right now, even if I wanted to.

EC5: I do feel any obligation to remain with my current employer.

EC6: Even if it were to my advantage, I do not feel it would be right to leave my job now.

Employee tenure intention

ETI1: I will most probably stay in this job in the foreseeable future.

ETI2: I definitely intend to maintain my current relationship with this job.

ETI3: I have no intention of leaving this job.