Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versão On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.17 no.3 Pretoria Jul. 2014

ARTICLES

The influence of 'buffering' variables on clients' willingness to engage in retribution behaviour after a service failure

Christo Boshoff

Department of Business Management, University of Stellenbosch

ABSTRACT

Much of the current service failure and recovery literature centres on reactive, post hoc measures that managers can take to address service failure. More importantly, much of the reported research has focused on managerial mechanisms under the direct control of service managers. This study shows that by viewing their responsibilities more broadly than only their narrow service-related goals, service managers can do much to prevent disgruntled clients from switching to competing service providers.

A thousand clients of a commercial bank who complained about a service failure completed an online questionnaire. Following a thorough assessment of the construct validity of the measurement model, the mediating role of brand superiority and corporate reputation was assessed by means of structural equation modeling. The results reveal that both brand superiority and reputation mediate the relationship between negative word-of-mouth and intentions to switch to a competing service provider, following a service failure.

The results show that by enhancing the firm's brand superiority and corporate reputation, service firms can build a 'buffer' that can deter clients who have suffered a service failure from switching to a competing service provider. In other words, service managers should broaden their organisational involvement by participating in activities such as strategic planning, corporate reputation management, and the planning of brand strategies and positioning strategies, as these variables can prevent complaining clients from ending their relationship with the offending service provider. The results, by implication, caution service managers against a myopic view of their role in the service organisation.

Key words: buffering variables, service failure, service recovery, negative word-of mouth, brand superiority, corporate reputation

JEL: M300

1 Introduction

A diverse range of environmental factors exerts pressure on service firms to retain their customers. Competition is an obvious example. In the case of financial service providers competition can take many forms: new local market entrants, competition from foreign banks and at one stage unanticipated forms of competition such as internet banking and today, shadow banking (Soros warns on China's shadow banking risks (Business Day, 2013)) and virtual money such as bitcoins (Pressman, 2013), to name but a few. Regulatory changes can also create pressure on service firms to manage the loyalty of their customers. The Banking Association of South Africa (BASA) has recently announced its intention to make it easier for banking clients to switch banks (Lefifi, 2011). One obstacle to switching banks that will be removed is the retention of the client's bank account number - a facility similar to that available to the clients of cellphone companies. The practice that bank customers are practically locked into a permanent relationship with their bank due to the inconvenience of switching to an alternative service provider is increasingly seen by some governments as an anticompetitive barrier, and they have argued for an arrangement where customers can retain their bank account number despite switching banks (known as account portability or 'porting').

The proposed move will place considerable pressure on banks to retain their existing customers - particularly those who experience unsatisfactory service from their bank. If clients experience a service failure, they can be expected to reconsider their relationship with the service provider. This reconsideration might result in the decision to stay; or, out of sheer frustration and disappointment, they might engage in retribution behaviour such as negative word-of-mouth or switching to a competitor.

Several studies have been conducted to investigate what service managers can do to prevent switching behaviour. These include the role of relationship-building (Satjos, Brodie & Whittome, 2010) and the role of the reputation of the firm (Hess, 2008). Almost all these studies have investigated the influence of variables over which service managers have direct control, such as the building of trust, relationship building or service excellence.

In addition, much of the research on the impact of service failure and recovery on outcomes and dependent variables have relied on the study of bivariate relations. However, in a consumer behaviour context these relationships are often modified by other variables such as covariates, moderators and mediators. In the case of a mediator the influence of an antecedent is transmitted to a consequence through an intervening variable (James & Brett, 1984:307) which may better explain people's behaviour (Baron & Kenny, 1986:1173) than bivariate relations. In service recovery-related research these potential influences (mediators and moderators) have largely been ignored.

As the variables under consideration in this study were hypothesised to be what Baron and Kenny (1986:1173) would describe as 'the generative mechanism' through which the focal independent variable influences the dependent variable, a mediation test (rather than a test of moderation) was appropriate.

Initially researchers investigating mediation relied on regression analyses to analyse the role of mediation (Fairchild & MacKinnon, 2009). However, Iacobucci, Saldanha and Deng (2007) have illustrated that structural equation modelling (SEM) is a superior technique to the use of regression analysis. In fact, they conclude that the use of SEM in this context is not merely an alternative but '... should supplant regressions' (Iacobucci et al., 2007).

Against this background, this study used structural equation modelling to assess the potential mediating effect of two variables over which a service manager has no direct control (corporate reputation and brand superiority) in mediating the impact of negative word-of-mouth on switching intentions among banks clients who have experienced service failures.

The primary purpose of this study is to investigate whether there are variables that the service managers do not have direct control over (do not have line responsibility for), but that can deter customers who have experienced a service failure from engaging in retribution-type behaviours such as negative word-of-mouth or switching to a competing firm. More specifically, are there mechanisms that service managers can use to convey or signal to their customers, in an indirect manner, that switching to a competitor may be a less than optimal decision?

2 Signaling theory

Signaling theory has its origin in economics, and refers to a situation where one party credibly communicates information about itself to another party. It is rooted in information asymmetry, where there is an inequality in information access that disrupts the normal market for product or service exchanges. Information asymmetry is resolved when one party signals some relevant information to the other party, who can then interpret the signal and change their behaviour in response to the signal received (Erdem & Swait, 1998). Signaling theory's relevance for marketing relates to situations when firms use signals to convey credibility to customers. Marketers use various tools to signal information to customers to convey credibility, including advertising, building a favourable reputation, pricing, coupons, slotting allowances, warranties, money back guarantees, and branding (Kirmani & Rao, 2000).

The information economics perspective of brand equity has its roots in signaling theory, where the brand is an entity that signals information about the firm to customers to convey credibility. When customers are unsure of product attributes, they rely on information signaled by the brand as a testament to the credibility of its product or service claims (Erdem & Swait, 1998). A brand plays a particularly important role in managing customer churn in relational-type services. Empirical findings based on information economics show that brand credibility significantly enhances word-of-mouth and reduces switching behaviours among customers (Sweeney & Swait, 2008).

Based on the signaling perspective of brand equity, brand loyalty results from brand equity. If customers are satisfied after using the product or service, and their usage experience is consistent with the firm's claims, the value of the firm's credibility signaling increases, lowering perceived risks and information costs for customers. Satisfactory experiences increase the chance of repeat purchasing, which contributes to the formation of brand loyalty (Erdem & Swait, 1998).

The firm's reputation (or credibility) has a major influence on the signals' ability to reduce risks and motivate customers to adopt a product or service (Helm & Mark, 2007) or to stay loyal. Brand superiority and brand reputation can thus be used as signals to customers that impact their decision either to switch from that brand or to remain loyal (Erdem & Swait, 1998). In a service failure and recovery context, there are also signals that service firms can convey to aggrieved customers to buffer the firm against negative consequences following this service failure.

3 Buffering variables

A variety of variables have been investigated that could influence a customer's response to a service failure and the likelihood of switching. These include its brand image (Aaker, Fornier & Brasel, 2004; Tax, Brown & Chandrashekaran, 1998), customer's perceptions of value (Satjos et al., 2010), the rapport the firm has with its clients (DeWitt & Brady, 2003), its reputation (Hess, 2008), trust and emotions (DeWitt, Nguyen & Marshall, 2008), affective commitment (Evanschitzky, Brock & Blut, 2011; Ganesan, Brown, Mariadoss & Ho, 2010), and the prevailing relationship (Satjos et al., 2010). Colgate, Tong, Lee and Farley (2007) distinguish between switching barriers (too much time and effort, lack of alternatives and high switching cost) and affirmatory factors (confidence in the service provider, social bonds and service recovery).

In a service recovery context, these variable have been referred to by a variety of names including switching barriers (DeWitt & Brady, 2003), protective layers (Satjos et al., 2010), buffer variables (DeWitt & Brady, 2003) and having an 'inoculation effect' (DeWitt & Brady, 2003). Whatever the terminology used, they exert the same influence in the sense that they can be expected to reduce the negative outcomes of a service failure and, in particular, the probability of switching to an alternative service provider. However, the degree of managerial control over these variables may not always be the same.

3 Direct managerial control

In the management literature, a distinction is drawn between the variables over which managers have direct control, those they can influence but do not have control over, and the ones over which they have no control. The marketing manager of a firm will, for instance, have direct control over its marketing objectives, its positioning strategy and its product mix. The same manager may be able to exert some influence on the firm's production targets, but have no control over interest rates or new legislation.

Service managers are generally responsible for the operational and functional aspects associated with service delivery. These will include aspects such as recruiting and placing suitably-qualified employees in (boundary-spanning) service delivery positions, training and development, managing the service environment, measuring and assessing customers' satisfaction with service delivery, relationship building, and putting systems and procedures in place to handle customer complaints.

These are aspects of service delivery that are under the direct control of the service manager - or what Smith, Bolton and Wagner (1999:362) describe as highly actionable by managers'. These and related managerial issues have been studied extensively. However, there are other managerial variables over which service managers have very little control, and can only influence at best. These can be described as internal organisational issues, and may include:

a) Efforts to build and enhance the corporate reputation.

b) Brand-building efforts and, in particular, efforts that try to establish a superior brand image.

c) Switching cost.

d) Non-core benefits that are granted to customers as a 'reward' for doing business with the service provider and, by implication, for remaining loyal.

The point of departure of this study is that there are managerial variables over which service managers have no direct responsibility or control, but that can deter a customer who has experienced a service failure and recovery from spreading negative word-of-mouth, or from switching to a competing service provider. Hess (2008) refers to these types of variables as 'buffering' variables - ones that can insulate the firm against the negative consequences of service failure. In this study, two variables are considered as mediating variables between negative word-of-mouth following a service failure on the one hand and planned switching behaviour on the other hand, namely corporate reputation and brand superiority. This broad hypothetical relationship is consistent with the cognitive psychology perspective that attentional processes can intervene between stimulus and behaviour (Stacy, Leigh & Wiengardt, 1994).

4 Customer switching behaviour

Switching is a highly undesirable situation for business firms, as it obviously implies a loss of potential income (Keaveny, 1995). The reasons customers switch to alternative service providers vary widely, and are often influenced by the alternative options available to them (Roos, Edvardsson & Gustasson, 2004), price, service failure and inconvenience (Keaveny, 1995), among others. For service customers, switching between service suppliers is costly in many ways, and there is a clear disincentive to do so. Barriers to switching include set-up costs, contractual costs, psychological costs, financial costs (Burnham, Frels & Mahajan, 2003), social switching costs, lost benefits costs and procedural costs (Jones, Reynolds, Mothersbaugh & Beatty, 2007:336). Switching costs often deter customers from switching to an alternative supplier (Polo & Sese, 2009), and consumers will thus only switch if they see sufficient benefit in such a move, either by saving money or by improving prevailing benefits. In a service failure situation -especially when followed by an unsatisfactory service recovery effort from a service firm -switching can be an emotion-driven response (Strizhakova, Tsarenko & Ruth, 2012), particularly if a feeling of betrayal is present (Gregoire & Fisher, 2008; Gregoire, Tripp & Legoux, 2009).

4.1 Brand superiority

The importance of branding, brand management and brand equity for almost all business firms cannot be disputed. Due to the impact that a brand has on a consumer's thoughts, words and actions, a brand creates equity - the intangible value added to a product. It is thus not surprising that brand equity has been described as 'one of the most important intangible assets of a firm' (Leone, Rao,

Keller, Luo, Mc Alister & Srivasta, 2006:

126). The benefits of branding and brand equity have been adequately described in the literature (Aaker, 1996; Keller, 2003); but it is the ability to reduce the firm's risks (De Chernatony & McDonald, 2003) - such as the risk of customer switching and vulnerability to competitive action (Leone et al., 2006) - that is particularly relevant in this study.

Surprisingly little research has been conducted into the role of brand equity in a services environment, and even less into its role in service failure and recovery context. In one of the rare exceptions, Tax et al. (1998) have demonstrated that brand image influences how consumers respond to service failures. In a similar vein, Aaker et al. (2004) reported that branding can play a role when 'transgressions' occur. Sweeney and Swait (2008) found that credibility significantly enhances word-of-mouth and reduces switching behaviours.

4.2 Corporate reputation

Given the fact that services are characterised primarily by their intangibility (Murray, 1991; Murray & Schlacter, 1990), some argue that a favourable reputation for a service firm is even more important than for those marketing physical entities. 'We're not like Coca-Cola where people buy the product off the shelf or from a vending machine ... ' says Joan Lollar of FedEx (Alsop, 2004:5), when discussing the importance of this service firm's reputation.

The benefits of a favourable corporate reputation have been well documented. These benefits include higher levels of positive word-of-mouth, and even the luxury of charging a premium price. Other benefits usually cited when describing the advantages of a favourable reputation include high levels of trust among customers, lower risk perceptions, and higher entry barriers for potential competitors (Walsh & Beatty, 2007). Particularly important to this study is the fact that in a crises-type situation a positive reputation can be particularly valuable as it creates a 'halo effect' that 'protects' the firm, at least to some extent, against harm (Coombs & Holladay, 2006), consistent with the buffering effect investigated in this study.

The role that reputation for service quality plays in a service failure has been investigated by Hess (2008) who found that a firm's reputation for service quality enhances intentions to repurchase, but does not influence word-of-mouth intentions. He also found that a firm's reputation for service quality moderates the relationship between service failure severity and satisfaction. However, the buffering effect of a firm's reputation for service quality was stronger in mild service failures than in more severe service failures (Hess, 2008).

Several caveats remain, however. The mediating role of corporate reputation in a service failure and recovery situation has not been explored. Nor has the potential impact of brand superiority on complaining customers' actions and behaviour been adequately addressed.

The work of Hess (2008) and Tax et al. (1998) is thus extended in this study by investigating the mediating role (as opposed to moderation) of brand superiority and corporate reputation (as opposed to service quality reputation), while the dependent variable is switching intentions rather than repurchase intentions.

5 Research questions

Against this background, the basic research question is: Can variables, described as 'buffer variables', over which service managers and service providers have no direct control, reduce the likelihood of dysfunctional behaviours following a service failure? More specifically, once a service failure has occurred and the aggrieved customer engages in negative word-of-mouth, can buffer variables prevent them from switching to another competing bank? To address these questions, the role of two intervening variables - corporate reputation and brand superiority - in customer complaint handling is investigated.

6 Dependent, independent and mediating variables

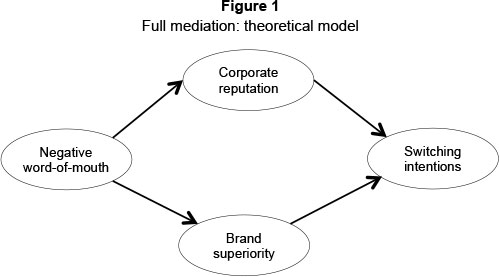

The dependent variable in this study is the intention to switch to a competing service provider. The mediating variables in this study are (a) a favourable corporate reputation, and (b) consumer perceptions of brand superiority. The model that will be empirically assessed is depicted in Figure 1. As all the variables in the model were measured with multiple indicators, the model was empirically assessed by means of a Structural Equation Modelling approach as recommended by Holmbeck (1977:602) and Iacobucci et al. (2007:152), using LISREL 8.80 (Joreskog & Sorbom, 2004).

7 Hypotheses

To assess the influence of the mediating effect of the two variables, the following hypotheses were considered to test for a full direct effect (see Figure 1):

H01: The full indirect effect of brand superiority and corporate reputation on switching intentions is equal to zero.

H1a: The full indirect effect of brand superiority and corporate reputation on switching intentions is not equal to zero.

8 Methodology

8.1 Sampling

A sample of 1 000 clients of a commercial bank were randomly selected from a commercial bank's client base. Following a qualification question 'Have you complained to XYZ bank during the past 12 months'? In total 261 respondents indicated that they had complained to the bank about a service failure during the preceding 12-month period. The data were collected by a commercial marketing research firm by means of an online survey.

8.2 Measurement

Respondents were asked to complete an online questionnaire consisting of 22 statements, all linked to a 7-point Likert-scale, where a 7 means 'Strongly Agree' and a 1 means 'Strongly Disagree'.

Negative word-of-mouth was measured with a 4-item questionnaire adapted from Price and Arnould (1999). Intention to switch banks was measured on a 3-item scale. Corporate reputation was measured using an 11-item scale based on the work of Walsh and Beatty (2007). As a properly validated instrument is not currently available to measure brand superiority, the four items used to measure this construct were self-generated, but were loosely based on the work of Mahashwaran (1994).

9 Construct validity assessment

9.1 Discriminant validity

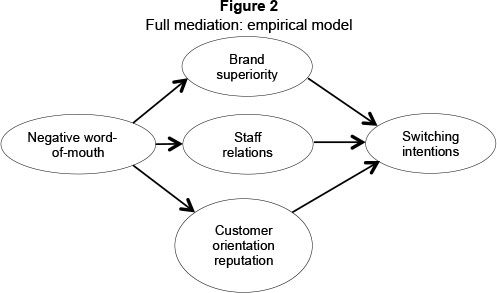

As poor discriminant validity can compromise the results in a structural equation analysis, the first step in the model testing procedure was to assess the discriminant validity among the latent constructs in the proposed model. For this purpose, an exploratory factor analysis, as recommended by Farrell (2009), was conducted. A principal-axis exploratory factor analysis with a direct quartimin oblique rotation revealed the most interpretable factor structure. A loading > 0.35 was regarded as significant. Table 1 shows that two items expected to measure corporate reputation (XYZ Bank offers good value for money; XYZ Bank seems to be environmentally responsible) loaded with the brand superiority items on Factor 1. The items expected to measure corporate reputation split into two dimensions. Factor 2 contains items typically associated with a firm's reputation for harmonious staff relations. However, two other corporate reputation items referring to how the bank treats its clients loaded on a separate factor (Factor 4), and were named 'customer orientation reputation'. As a result, three intervening variables were specified instead of just two as depicted in Figure 2. In other words, a third intervening variable, reputation for harmonious staff relations, was added. One word-of-mouth (WOM) item was deleted as it did not load to a significant extent on any factor. All three of the intentions to switch items loaded as expected.

Six items had to be deleted due to poor discriminant validity, as suggested by Farrell and Rudd (2009). Table 1 also shows that the items used to measure the latent variables in this study demonstrated sufficient discriminant validity.

9.2 Reliability assessment

Table 1 shows that all the internal consistency scores exceeded the customary cut-off value of 0.7 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994) with one exception. In the case of the customer orientation factor the Cronbach Alpha score is 0.692. Only the remaining 16 items listed in Table 1 were used in subsequent analyses.

9.3 Assessing multivariate normality

As the choice of an estimation method in structural equation modeling is influenced by the distributional properties of the data, the first step in the confirmatory factor analysis phase of the study was to assess the multivariate normality of the data.

The null hypotheses considered were:

H02: The data demonstrate sufficient evidence of multivariate normality.

H2a: The data do not demonstrate sufficient evidence of multivariate normality

To assess the multivariate normality of the data (skewness and kurtosis), the computer programme LISREL 8.80 (Joreskog & Sorbom, 2008) was used. The test result (skewness and kurtosis χ2 = 786.295; p < 0.00l) revealed that the assumption of multivariate normality did not hold for this data set, suggesting that the null hypothesis (H02) had to be rejected. Due to the violation of the assumption of multi-variate normality, the more conventionally used maximum likelihood (ML) could not be used (Joreskog & Sorbom, 2008). Under such circumstances, Satorra and Bentler (1988, 1994) proposed that the Robust Maximum Likelihood (RML) estimation method be used.

9.4 Construct validity: Model fit of the measurement model

How well data fit a proposed theoretical model is an indication of construct validity. To assess the model fit, the following null hypotheses were formulated:

H03: RMSEA = < 0.05

H3a: RMSEA = > 0.05

An inspection of the p-value of the test of a close fit (p = 0.994) confirmed that the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, suggesting that the data fit the model closely. The other fit statistics confirmed this conclusion: (χ2 = 107.07; p < 0.00), χ2Μ ratio = 1.138; RMSEA = 0.0233; ECVI = 0.743). However, as pointed out by Farrell and Rudd (2009), one cannot rely on fit indices alone to assess a model's construct validity.

9.5 Construct validity: Convergent validity of the measurement model

In addition to the fit indices, an inspection of the factor loadings revealed that they all exceeded 0.75 and were statistically significant, which can be regarded as evidence of convergent validity (Hair et al., 2006; Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, 2000:89).

10 Mediation assessment

As there is no point in testing for a mediation effect if there is no relationship between the independent variable (negative word-of-mouth in this study) and the dependent variable (intention to switch in this study) in the first place (Holmbeck, 1977:600) a latent variable regression analysis using LISREL 8.80 was conducted to assess the influence of negative word-of-mouth on intentions to switch.

The influence proved to be highly significant (t-value = 14.09; p < 0.000). This result leads to the research question: Can service managers, besides their direct line responsibilities, be involved in other activities that can restrain dissatisfied customers from switching to a competitor?

To address this question a full mediation model was specified where the direct influence of the exogenous variable (negative word-of-mouth) on the endogenous dependent variable (switching intentions) is excluded (see Figure 2).

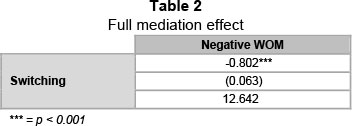

To assess the full mediating effect of brand superiority, staff relations reputation and customer orientation reputation between negative word-of-mouth (NWOM) on one hand, and switching intentions on the other, the following null and alternate hypotheses were considered (in other words, H01 had to be re-formulated):

H04: The full indirect effect of brand superiority, corporate reputation and staff relations reputation on switching intentions is equal to zero.

H4a: The full indirect effect of brand superiority, corporate reputation and staff relations reputation on switching intentions is not equal to zero.

The hypothesis was addressed using the programme LISREL 8.80 and the analysis yielded a p-value of 0.323 when testing the hypothesis of a close fit, suggesting that the hypothesis of a close-fitting model (Figure 2) cannot be rejected.

The results reported in Table 2 suggests that there is sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis (H04) in favour of the alternate hypothesis. Table 2 thus reveals that the full mediation effect of negative word-of-mouth (NWOM) on switching intentions is significant at the 1% level of significance. In addition the independent variables explain 71.3% of the variation in switching intentions. In other words, perceptions of brand superiority, staff relations reputation and customer orientation reputation among bank clients who have complained to a bank about a service failure mediate the effect or influence of negative word-of-mouth (NWOM) on switching intentions (SWITCH).

To address the secondary question of the relative influence of these mediating variables the magnitude of the indirect effect of negative word-of-mouth (NWOM) on switching intentions (SWITCH) of each of the three paths were calculated by multiplying the completely standardised Gamma and Beta estimates in each one of the three indirect paths. The total indirect effect was thus calculated by summing the indirect effects across the three mediated paths. In this way the contribution of each of the individual mediation effects to the total indirect effect of negative word-of-mouth (NWOM) on switching intentions (SWITCH) can be determined. This analysis suggests that the path mediated by brand superiority produces the strongest indirect effect (-0.729) compared to that of staff reputation (-0.095) and corporate reputation (0.022). It must be noted, however, that the statistical significance of the individual indirect or mediated effects could not be assessed.

11 Conclusions and managerial implications

The empirical results reported in this study reveal that perceptions of brand superiority, corporate reputation and staff relations reputation can serve as buffering variables among bank clients who have complained to a bank about a service failure. In other words, if clients of a bank complain to a bank and spread negative word-of-mouth about the bank as a result, this negativity will not necessarily be converted into actual switching, provided that they believe that the bank has a superior brand, a favourable corporate reputation, and a reputation for treating their staff well.

The results suggest that service managers must take care not to be what Levitt (1960) would have described as a 'myopic' view of their role in the organisation. In other words, it appears that service managers can benefit indirectly from not seeing their organisational involvement too narrowly. Getting involved in decision-making for which they may not have direct responsibility may yield indirect benefits that can enhance their own goal realisation efforts.

One of the dangers of 'classic' myopia is insensitivity to changing consumer needs (Richard, Womack & Allaway, 1992). It is thus disconcerting to note that a recent survey by the consulting firm Accenture found that while nearly three-quarters (73 percent) of the business executives they surveyed said that consumer behaviour had changed markedly in the previous three years, a similar proportion (74 percent) said they did not fully understand the consumer changes that were under way -and even more (80 percent) said they believed that their companies were not taking full advantage of the opportunities these changes present (Accenture, 2012).

Modern-day service consumers demand more than just 'good' service (McDonald, 2012) and are often attracted to the aspirational benefits of firms such as a superior brand (Keller, 2001). In addition, they are often reluctant to do business with firms with a poor reputation or one that has suffered reputational damage (Alsop, 2004). These are consumer concerns that service managers cannot regard as someone else's responsibilities.

The results of this study show that service managers can benefit by getting involved in activities such as strategic planning and the planning of brand strategies, and that this involvement can indirectly benefit the service managers' own service-delivery related endeavours.

In some (particularly larger) firms, the management of corporate reputation may be regarded as the responsibility of the public relations department, or even of external consultants. The results of this study demonstrate that by divorcing themselves from involvement in the management of the firm's corporate reputation, service managers may deprive themselves of the opportunity to enhance their own service delivery and service recovery efforts.

When writing about service recovery, researchers often focus on retrospective or post hoc actions and strategies. Proposing actions such as 'returning a dissatisfied customer to a state of satisfaction' or apologising, or showing empathy and analysing complaint data (Van Vaerenbergh, Lariviere & Vermeir, 2012) is, without question, important. However, there are clearly other managerial actions that can do much to prevent undesirable outcomes such as customer switching.

12 Limitations and future research

A limitation of this study is that no attempt was made to distinguish between 'major' and 'minor' complaints. It may be that, in the case of severe service failures, the buffering variables investigated in this study may not deter a complaining client from switching to a competitor. This limitation leaves scope for future research.

References

AAKER, D.A. 1996. Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California Management Review, 38(3):102-120. [ Links ]

AAKER, J.L., FOURNIER, S. & BRASEL, A.S. 2004. When good brands do bad. Journal of Consumer Research, 31 (June):1-16. [ Links ]

ACCENTURE. 2012. Businesses that capitalize on consumerbehaviour change are better positioned to outperform economic growth, finds Accenture. Available at: http://newsroom.accenture.com/news/businesses-that-capitalize-on-consumer-behaviour-change-are-better-positioned-to-outperform-economic-growth-finds-accenture.htm, published on 22 January 2012 [ accessed 2013-03-08]. [ Links ]

ALSOP, R.J. 2004. The 18 immutable laws of corporate reputation: Creating, protecting, and repairing your most valuable assets, Kogan Page, London. [ Links ]

BARON, R.M. & KENNY, D.A. 1986. The moderator-mediator distinction in social psychology research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6): 1173-1182. [ Links ]

BURNHAM, T., FRELS, J.K. & MAHAJAN, V. 2003. Consumer switching costs: A typology, antecedents and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31 (Spring): 109-126. [ Links ]

BUSINESS DAY. 2013. Soros warns on China's shadow banking risks. Business Day, 9 April, p. 14. [ Links ]

COLGATE, M., TONG, V.T., LEE, C.K. & FARLEY, J.U. 2007. Back from the brink: Why customers stay. Journal of Service Research, 9(3):211-228. [ Links ]

COOMBS, W.T. & HOLLADAY, S.J. 2006. Unpacking the halo effect: Reputation and crisis management. Journal of Communication Management, 10(2):123-137. [ Links ]

DE CHERNATONY, L. & MCDONALD, M. 2003. Creating Powerful Brands (3rd ed.) Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinneman. [ Links ]

DEWITT, T. & BRADY, M.K. 2003. Rethinking service recovery strategies: The effect of rapport on consumer responses to service failure. Journal of Service Research, 6(2):193-207. [ Links ]

DEWITT, T., NGUYEN, D.T. & MARSHALL, R. 2008.Exploring customer loyalty following service recovery. Journal of Service Research, 10(3):269-281. [ Links ]

DIAMANTOPOULOS, A. & SIGUAW, J. 2000. IntroducingLISREL. London, UK: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

ERDEM, T. & SWAIT, J. 1998. Brand equity as a signaling phenomenon. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 7(2):131-157. [ Links ]

EVANSCHITZKY, H., BROCK, C. & BLUT, M. 2011. Will you tolerate this? The impact of affective commitment on complaint intention and postrecovery behaviour. Journal of Service Research, 14(4): 410-425. [ Links ]

FAIRCHILD, A. J. & MACKINNON, D.P. 2009. A general model for testing mediation and moderation effects. Prev Sci, 10(2):87-99. [ Links ]

FARRELL, A. 2009. Insufficient discriminant validity: A comment on Bove, Pervan, Beatty and Shiu. Journal of Business Research, 63:324-327. [ Links ]

FARRELL, A. & RUDD, J.M. 2009. Factor analysis and discriminant validity: A review and some practical issues, Proceedings of the Australia-New Zealand Marketing Academy's Conference. [ Links ]

GANESAN, S., BROWN, S.P., MARIADOSS, B.J. & HO, H. 2010. Buffering and amplifying effects of relationship commitment in business-to-business relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 7(2):363-373. [ Links ]

GREGOIRE, Y. & FISHER, R. 2008. Customer betrayal and retaliation: When your best customers become your worst enemies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36:247-261. [ Links ]

GREGOIRE, Y., TRIPP, T.M. & LEGOUX, R. 2009. When customer love turns into lasting hate: The effects of relationship strength and time on customer revenge and avoidance. Journal of Marketing, 73 (November): 18-32. [ Links ]

HAIR, J.F., BLACK, W.C., BABIN, B.J., ANDERSON, R.E. & TATHAM, R.L. 2006. Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.) Pearson Prentice Hall, New Jersey. [ Links ]

HELM, R. & MARK, A. 2007. Implications from cue utilisation theory and signalling theory for firm reputation and the marketing of new products. International Journal of Product Development, 3(3-4): 396-411. [ Links ]

HESS, R.L. 2008. The impact of firm reputation and failure severity on customers' responses to service failures. Journal of Services Marketing, 22(5):385-398. [ Links ]

HOLMBECK, G.N. 1977. Toward terminological, conceptual and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(4):599-610. [ Links ]

IACOBUCCI, D., SALDANHA, N. & DENG, JX. 2007. A meditation on mediation: Evidence that structural equations models perform better than regressions. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(2):140-154. [ Links ] JAMES, L.R. & BRETT, J.M. 1984. Mediators, moderators and tests for mediation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(2):307-321. [ Links ]

JONES, M.A., REYNOLDS, K.E., MOTHERSBAUGH, D.L. & BEATTY, S.E. 2007. The positive and negative costs of relational outcomes. Journal of Service Research, 9(4):335-355. [ Links ]

JORESKOG K.G. & SORBOM, D. 2008. Non-normal data, Scientific Software International. Available at: http://www.ssicentral.com/lisrel/resources.html [accessed October 2012]. [ Links ]

JORESKOG K.G. & SORBOM, D. 2004. LISREL for Windows [computer software]. Lincoln, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc. [ Links ]

KEAVENY, S.M. 1995. Customer switching behavior in service industries: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing, 59 (April):71-82. [ Links ]

KELLER, K.L. 2003, Brand synthesis: The multidimensionality of brand knowledge. Journal of Consumer Research, 29 (March):595-600. [ Links ]

KELLER, K.L. 2001. Building customer-based brand equity: A blueprint for creating strong brands. Marketing Science Institute, Working paper 01-107. [ Links ]

KIRMANI, A. & RAO, A. 2000. No pain, no gain: A critical review of the literature on signaling unobservable product quality. Journal of Marketing, 64(2):66-79. [ Links ]

LEONE, R.P., RAO, V.R., KELLER, K.L., LUO, A.M., MCALISTER L. & SRIVASTA, R. 2006. Linking brand equity to customer equity. Journal of Service Research, 9(2):125-138. [ Links ]

LEFIFI, T.A. 2011. Switching bank accounts to be easier. Sunday Times Business Section, p.4. [ Links ]

LEVITT, T. 1960. Marketing myopia. Harvard Business Review, July-August:45-56. [ Links ]

MCDONALD, S. 2012. Great service just isn't enough anymore. Available at: http://yfptips.wordpress.com/2012/10/19/great-service-just-isnt-enough-anymore/ [accessed 2013-03-27]. [ Links ]

MURRAY, K.B. 1991. A test of services marketing theory: Consumer information acquisition activities. Journal of Marketing, 55 (January):10-25. [ Links ]

MURRAY, K.B. & SCHLACTER, J.L. 1990. The impact of services versus goods on consumers' assessment of perceived risk and variability. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 18(1):51-65. [ Links ]

MAHASHWARAN, D. 1994. Country of origin as a stereotype: Effects of consumer expertise and attribute strength on product evaluations. Journal of Consumer Research, 21 (September): 354-365. [ Links ]

NUNNALLY, J.C. & BERNSTEIN, I.H. 1994. Psychometric theory, McGraw-Hill, New York. [ Links ]

POLO, Y. & SESE, F.J.F. 2009. How to make switching costly: The role of marketing and relationship characteristics. Journal of Service Research, 12(2):119-137. [ Links ]

PRICE, L.L. & ARNOULD, E.J. 1999. Commercial friendships: Service provider-client relationships in context. Journal of Marketing, 63 (October):38-56. [ Links ]

PRESSMAN, A. 2013. Bitcoin's validity - and price - gets big boost from Baidu. The Exchange (Yahoo Finance blog). [ Links ]

RICHARD, M., WOMACK, J.A. & ALLAWAY, A.W. 1992. An integrated view of marketing myopia. The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 9(3):65-71. [ Links ]

ROOS, I., EDVARDSSON, B. & GUSTAFSSON, A. 2004. Customer switching patterns in competitive and noncompetitive service industries. Journal of Service Research, 6(3):256-271. [ Links ]

SATJOS, L., BRODIE, R.J. & WHITTOME, J. 2010. Impact of service failure: The protective layer of customer relationships. Journal of Service Research, 6(2):193-207. [ Links ]

SATORRA, A. & BENTLER, P.M. 1988. Scaling corrections for chi-square statistics in covariance structure analysis, in Proceedings of the Business and Economic Statistics Section of the American Statistical Association, American Statistical Association, VA:308-313. [ Links ]

SATORRA, A. & BENTLER, P.M. 1994. Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis, in Von Eye, A. & Clogg, C.C. (eds.) Latent variable analysis: applications to developmental research. Sage, Newbury Park:399-419. [ Links ]

SMITH, A.K., BOLTON, R.N. & WAGNER, J. 1999. A model of customer satisfaction with service encounters involving failure and recovery. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(3):356-372. [ Links ]

STACY, A.W., LEIGH, B.C. & WEINGARDT, K.R. 1994. Memory accessibility and association of alcohol use and its positive outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psycho-pharmacology, 2:269-282. [ Links ]

STRIZHAKOVA, Y., TSARENKO Y. & RUTH, J.A. 2012. 'I'm mad and I can't get that service failure off my mind': Coping and rumination as mediators of anger effects on customer intentions. Journal of Service Research, 15(4):414-429. [ Links ]

SWEENEY, J. & SWAIT, J. 2008. The effects of brand credibility on customer loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 15(3):179-193. [ Links ]

TAX, S., BROWN, S.W. & CHANDRASHEKARAN, M. 1998. Customer evaluations of service complaint experiences: Implications for relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 62(2):60-76. [ Links ]

VAN VAERENBERGH, Y., LARIVIERE, B. & VERMEIR, I. 2012. The impact of process recovery communication on customer satisfaction, repurchase intentions, and word-of-mouth intentions. Journal of Service Research, 15(3):262-279. [ Links ]

WALSH, G. & BEATTY, S.E. 2007. Customer-based corporate reputation of a service firm: Scale development and validation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(1): 127-143. [ Links ]

Accepted: December 2013

APPENDIX A

Negative word-of-mouth

WOM1: I would not recommend XYZ to someone who asks me for advice

WOM2: I do not say positive things about XYZ to others

WOM3: I tell others about it when XYZ gives me poor service

WOM4: I am fairly negative about XYZ when talking to others about banks

Intention to switch

SWITCH1: I will soon switch to another bank

SWITCH2: I plan to stop doing business with XYZ in the near future

SWITCH3: It is time to move my business to another bank

Corporate reputation

CREP1: XYZ's employees are concerned about customer needs

CREP2: XYZ's services are of a high quality

CREP3: XYZ has employees who treat customers courteously

CREP4: XYZ seems to treat its employees well

CREP5: XYZ's management seems to pay attention to the needs of its employees

CREP6: XYZis financially sound

CREP7: XYZ is well-managed

CREP8: XYZ seems to be environmentally responsible

CREP9: XYZ stands behind the services that it offers

CREP10: XYZ offers services that are good value for money

CREP11: XYZ seems to make an effort in protecting the jobs of its employees

Brand superiority

BRAND1: XYZ is superior compared to other competing banks

BRAND2: XYZ is the leading bank in the country

BRAND3: XYZ has a better image than other banks

BRAND4: People are more aware of XYZ than any other bank