Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versão On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.17 no.2 Pretoria Fev. 2014

ARTICLES

Capital gains tax in South Africa: perceptions of fairness?

Warren MarounI; Magda TurnerI; David ColdwellII

ISchool of Accountancy, University of the Witwatersrand

IISchool of Economic and Business Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

ABSTRACT

Regulatory developments are often presented as being in the public interest but recent studies on corporate governance have suggested otherwise. In some cases, regulatory change is driven more by the self-interest of the political elite than by the need for substantive reform. This paper adds to this debate by considering whether capital gains tax (CGT) in South Africa is an example of a genuine attempt to improve the perceived fairness of the tax system or whether perceptions of fairness are being used simply to further political agendas. The paper concludes that the latter may be the case. South Africa is used as a case study because of the fairly recent introduction of CGT, as an example of a material amendment to tax policy, and because of the country's fairly recent transition to democracy.

Key words: black economic empowerment (BEE) schemes, capital gains tax (CGT), correspondence analysis, fairness, pubic benefit organisations (PBO), public interest, recreational clubs, regulatory reform, small businesses, South African tax system.

JEL: E30, H20

1 Introduction

This paper uses a correspondence analysis to shed light on the operation of the capital gains tax (CGT) in South Africa.1 Introduced in 2001, CGT was promoted as an important means of entrenching horizontal and vertical equity (Katz Commission, 1995), ensuring that the wealthy shoulder a heavier tax load and that taxpayers in equal economic positions incur an equivalent tax charge (Congress of South African Trade Unions [COSATU], 2001; Manuel, 2010). The projected increase in state revenues was also expected to make an important contribution to poverty alleviation strategies, particularly schemes for the upliftment of the previously disenfranchised (Voster, 2000; South African Revenue Services [SARS], 2000; Katz Commission, 1995). Accordingly, despite the fact that it imposed an additional tax burden on capital holders, CGT was celebrated as a means of promoting the fairness of the South African Tax System (Maroun, Turner & Sartorius, 2011).

Changes to tax policies are, however, frequently defended on the grounds of fairness (Farrar, 2011). In doing so, governments are able to create the impression of active reform that resonates with the principles of paying a fair share for state services in proportion to one's ability to do so (Vivian, 2006). This approach appeals to people's sense of moral rectitude or perception that they are acting for the collective benefit of society (COSATU, 2001; Katz Commission, 1995; Coetzee, 1998; Suchman, 1995). Confidence in government, political support and regulated conduct by citizens tend to be the result (Farrar, 2011). It may, however, be found that the trumpeted message of rational and fair reforms to the tax system is decoupled from the practical, but contrary, experiences of taxpayers (Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Suchman, 1995).

Much of the previous South African tax research is either mainly technical in nature (see Arendse, 2004a; Stiglingh, Koekemoer & Wilcocks, 2011) or grounded in positivist traditions (Coetsee & Stegmann, 2012; Maroun, 2012). Although this body of research has made a number of important contributions, it lacks critical bite, with the result that powerful political and social forces shaping local tax policies have been largely overlooked (Carruthers, 1995; Malsch & Gendron, 2011). The application of traditional "objective" methods to tax research also means that the emphasis has been on reporting factual findings, to the detriment of challenging the status quo and critically evaluating what might and should be happening when it comes to future changes to the tax system (Laughlin, 1995; see: Llewelyn, 1996; Ahrens et al., 2008; Brennan & Solomon, 2008; Humphrey, 2008).

In this light, this paper explores the tension between certain of the state's policy statements which maintain that CGT is a means of entrenching fairness in the South African tax system and the perceptions of taxpayers, informed by the benefits of personal experience, which point to underlying unfairness (Hayek, 1960). Using the seminal work of Smith (1776), which describes the characteristics of a fair tax system, we concentrate mainly on the CGT implications for black economic empowerment (BEE), public benefit organisations (PBO), and small- and medium-sized enterprises, given the key role that each plays in government's poverty alleviation plans. In doing so, the research offers a fresh perspective on CGT, complementing more technically oriented studies. Specifically, the research is inspired by a likeminded body of corporate governance research which points to the social, political and institutional forces which shape modern society, showing how similar processes may be at work when it comes to the development of tax policy2 (examples include Unerman & O'Dwyer, 2004; Laughlin, 2007; Smith-Lacroix, Durocher & Gendron, 2012). Finally, the paper makes an important methodological contribution by serving as one of the first examples of a mixed method study on South African tax grounded in a critical epistemology.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a review of the literature, establishes a theoretical framework and derives the components of the chosen survey instrument. Section 3 discusses the method. Section 4 examines arguments and counterarguments on the perceived fairness of CGT with respect to poverty alleviation strategies that include BEE schemes, PBO's and small business tax relief. Section 5 discusses the findings and section 6.

2 Literature review

In terms of the Eighth Schedule to the Income Tax Act 58 of 1962 (the Act), CGT is levied on certain capital assets disposed of by taxpayers on or after 1 October 2001 (Stiglingh et al., 2011). An "asset" is defined widely, and includes any:

1) property of whatever nature, whether movable or immovable, corporeal or incorporeal excluding any currency but including coins made mainly from gold or platinum; and

2) any right or interest of whatever nature to or in such property (para 1, Eighth Schedule to the Act).

The "capital gain" is determined by deducting from the proceeds on disposal (para 35, Eighth Schedule to the Act) the base cost of the asset (para 20 of the Eighth Schedule to the Act). An annual exclusion is available to reduce both capital gains and losses, leaving the aggregate capital gain or loss, for both natural persons and certain trusts. Assessed capital losses from the previous year's assessment may be used to reduce the aggregate capital gain or loss, leaving a net capital gain or assessed capital loss. A taxpayer's taxable capital gain for the year of assessment is the net capital gain for a taxpayer multiplied by the relevant inclusion rate applicable to the taxpayer. This resulting taxable capital gain is added to the taxpayer's taxable income and subject to normal income tax. A taxpayer's assessed capital loss cannot be set off against normal taxable income. Instead, it is carried forward to the next year of assessment where it can be used to reduce future realised aggregate capital gains or increase aggregate losses in subsequent years (paras 3-10, Eighth Schedule to the Act; s 26A of the Act). In this way, taxable capital gains become part of the total taxable income and are subject to normal tax rather than being subject to a unique tax. Nevertheless, in the interests of brevity, the term normally used is CGT (Stiglingh et al., 2011).

This overview of CGT is deliberately brief. The aim of this research is not to provide an extensive technical account of CGT. Instead, the research highlights inconsistencies between the State's initial arguments that CGT would improve the fairness of the South African tax system and current experiences of taxpayers, which suggest possible sources of injustice. To do so, we ground the debate on the effect of CGT on certain poverty alleviation schemes in the critical corporate governance literature and on the "elements" of a "fair" tax system identified in the seminal work by Smith (1776)3 (in Vivian, 2006). Consequently, this paper is highly normative. The paper intends, in the absence of a well-developed body of interpretive or critical South African tax literature, to identify "analogies, similarities and dualities" between the critical corporate governance literature and certain aspects of the Eighth Schedule to the Act, and by doing so aims to offer new perspectives on tax regulatory developments (Llewelyn, 1996; Llewelyn, 2003; Khalifa, Sharma, Humphrey & Robson, 2007).

2.1 Development of a theoretical framework and the correspondence analysis

Laws and regulations are often "marketed" to the electorate as pro-social and fair (Laughlin, 2007; Canada, Kuhn & Sutton, 2008; Farrar, 2011). The modus operandi fosters trust in governments, ensures compliance and ultimately serves to legitimise governments' policies in the eyes of voters (Kaplan & Ruland, 1991; Suchman, 1995; Farrar, 2011). In a corporate governance setting, new laws and regulations are, therefore, portrayed as contributing to economic efficiency, responding to prior failures and ultimately preserving confidence in the capital market system and respective regulatory body (Canada et al., 2008; Sy & Tinker, 2008; Tremblay & Gendron, 2011). More critical perspectives are, however, also possible.

Mitchell and Sikka (2004) explain that an apparently "objective" state of affairs is the product of competing political, social, economic and cultural forces (Foucault, 1977; Burchell, Clubb, Hopwood, Hughes & Nahapiet, 1980; Khalifa et al., 2007). Consequently, while "we may lament this state of the world, the fact is that policy making is inherently a political rather than a scientific process" (Humphrey, 2008:176), with the result that acting in the public interest and the furtherance of political self-interest frequently co-exist (Mitchell & Sikka, 2004; Tillema & ter Bogt, 2010; Malsch & Gendron, 2011). Explaining the promulgation of new laws and regulations, therefore, requires a consideration, not only of rational economic issues, but also of social and political factors which may provide their actual "raison d' etre" (Power, 1994; Humphrey, 2008).

Unerman and O'Dwyer (2004) provide a practical example, exploring the promulgation of the Sarbanes Oxley Act (2002). While ostensibly motivated by the need to improve the regulatory landscape following the demise of Enron, the researchers uncover a political dimension to the new law, suggesting that policy-makers may have been concerned about reassuring their constituencies of the sound functioning of capital markets in order to secure their places in government. Laughlin (2007) provides a similar account. He argues that financial reporting in the United Kingdom is characterised, at least to some extent, by the changing political attitudes of the country's leadership. The relevance of social and political forces is also highlighted in an auditing context by Sikka, Puxty, Willmott and Cooper (1998: 299), who argue that the objectives of audit are "constructed and transformed within the social relations of power", with the result that the meaning and objective of "audit" are a product of the accommodation of the professional interests of accountants and the political desires of the state.

A similar relationship between changes in tax policy and political interest and power may apply in a South African context (Llewelyn, 2003). In the debates preceding the introduction of CGT in 2001, proponents maintained that the tax on capital gains was "fair" in the sense that it was consistent with Smith's (1776) canons describing the elements of a "fair" tax system.4 Firstly, despite the concern that CGT would amount to a form of double tax, (Criterion 1 in Table 1), government took the position that wealthier taxpayers, including those who may have accumulated stores of capital wealth as a direct result of Apartheid, ought to be subject to tax upon the realisation of those gains (COSATU, 2001; African National Congress [ANC], 2010). The principles of horizontal and vertical equity meant that a taxpayer enriched by earning an income or realising an equivalent capital gain ought to suffer an equal tax charge (SARS, 2000; Roberts, 2006; Vivian. 2006). In other words, irrespective of the nature of the gain, for the tax system to be fair, the mere fact that a taxpayer had been enriched should be seen as sufficient grounds to levy tax (Vivian, 2006) (Criterion 2 in Table 1). Secondly, exempting capital gains from tax would leave vast stores of wealth, accumulated in the hands of an elite group of wealthy individuals, untaxed (Katz Commission, 1995). Capital taxes, even if a possible source of double tax, would be shouldered by wealthier taxpayers better able to bear the additional tax load, without undermining the ability of a taxpayer to support himself and his family (SARS, 2006; Roberts, 2006; Vivian, 2006) (Criterion 3 in Table 1). Finally, by increasing state revenues government would also be able to tackle nation-wide poverty more effectively with a number of better-funded schemes aimed at improving the plight of the historically disadvantaged (Criterion 4 in Table 1) (SARS, 2000; Voster, 2000; Manuel, 2001; Maroun et al., 2011).

Experience shows, however, that the intended benefits of GCT may not be a reality. In line with the arguments of Farrar (2011) and Marriott (2010), in the long run "fairness" may be found to take second place to the avowed intention of tax legislation. This brings us to the essential issue of this paper: are claims that fairness is being entrenched in the tax system bona fide or expedient? To explore this in more detail, we consider three primary poverty alleviation schemes identified by government which have direct relevance to CGT: Black economic empowerment schemes (BEE), relief measures for small and medium-sized entities, and preferential treatment for public benefit organisations (PBOs) and recreational and sports clubs (clubs) (Manuel, 2006, 2009, 2010).

2.2 BEE schemes

BEE is designed to champion the interests of non-white South Africans with the aim of redressing economic imbalance. Examples of BEE schemes include specific government grants, preferential employment opportunities and, of particular relevance for this paper, the offering of equity stakes in enterprises to the historically disadvantaged (Arendse, 2004a; COSATU, 2011; Democratic Alliance, 2011). In keeping with the principle that wealthier taxpayers ought to have a higher tax charge, government took the position that BEE schemes should be subject to specific CGT relief, mainly in the form of "roll-over provisions" when certain capital assets are disposed of (Arendse, 2004a).

These have, however, been criticised for amounting to little in substance. Many of the roll-over provisions (s 41-s 47 of the Act) are highly complex and difficult to apply in practice (Arendse, 2004b; Olivier, 2007; Stinglingh et al., 2011). For example, definitions of a "group of companies" in the Act, which form a basis for the required CGT relief, are inconsistent with many BEE charters, leading to unfavourable tax consequences (Arendse, 2004b; Stinglingh et al, 2011). Provisions dealing with capital losses constitute a second stumbling block, often ring-fencing these losses, to the detriment of effective tax planning by BEE schemes (Arendse, 2004a; s 41 of the Act). As a result, when it comes to these initiatives, the levying of CGT could be tantamount to the State's offering a measure of assistance with the one hand, and then retracting part of it with the other through the application of additional tax (Arendse, 2004b).

Further, the BEE relief measures stop short of exempting capital gains from CGT. Although this is consistent with the notion of taxpayers' paying tax on gains irrespective of the nature of those gains, critics have maintained that capital formation and protection, especially when it comes to emerging businesses, are fundamental for long-term poverty alleviation (Dyl, 1977; Moore & Silva, 1995; Conda, 2006). In the long run, CGT may, paradoxically, amount to a double tax that undermines the state's revenue collection, to the detriment of the poor (Vivian, 2006; Stein, 2000; Voster, 2000; Ricardo, 1817). Rather than being heralded as a success, CGT has, therefore, been lambasted for stifling innovation and entrepreneurship (Stein, 2000).

In contrast, SARS has stressed the evolutionary nature of its tax reform process. At the time of the introduction of CGT, no provisions existed which recognised a group of companies as an economic unit in order to provide CGT relief to BEE schemes (Harrison, 2001:4). The South African government reassured taxpayers that ongoing improvements would be made (Ensor, 2001a; Ensor, 2001b; Manuel, 2007; Manuel, 2010). The conclusion reached was that any practical difficulty encountered when applying the "roll-over" provisions of ss 41-47 of the Act would not constitute a material source of unfairness. In a recent announcement, however, government suspended the operation of the "roll over provisions" on the basis that they were being used in tax avoidance schemes and therefore detracted from the fairness of the tax system.

Statement 1: CGT taxes only the wealthy.

Statement 2: CGT promotes the equal taxing of taxpayers in equal economic positions.

Statement 3: The CGT effects of ss 41 to s 47 of the Act pose difficulties for BEE deals.

2.3 Public benefit organisations and recreational clubs

Critics have argued that CGT, by resulting in a higher tax load, thwarts the philanthropic efforts of PBOs and certain clubs working for charitable ends (Mitchell, 2006; South African Council of Churches (SACC), 2006). The Minister of Finance (Manuel, 2001) and SARS (Manuel, 2006) defended levying CGT on these taxpayers as a means of standardising tax practice and closing avoidance loopholes that relied on the tax-exempt status of certain classes of taxpayers (SARS, 2008; Manuel, 2010). By reducing, but not eliminating, the CGT exemption for PBO's and clubs, government concluded that it had successfully balanced the goals of protecting the tax base while ensuring that PBOs and clubs were not unable to bear the tax load (SARS, 2004; s 10 of the Act; para 64 of the Eighth Schedule to the Act). The respective CGT relief provisions, like the BEE equivalents, are, however, complex and difficult to apply in practice. For example, where an asset is used for the dual purpose of earning rentals and directly in charity initiatives, CGT relief may be foregone. Consequently, a PBO or club may choose to leave assets idle, rather than use them for rentals to finance additional charity work. The fact that a social welfare loss may result from unfavourable CGT treatment does not seem to have been taken into account (Mitchell, 2006: 137; SACC, 2006; para 65B of the Eighth Schedule to the Act).

Government has stressed, however, that PBOs and recreational clubs form an integral part of its plans to tackle poverty and contribute positively to community development. It maintains that failure to exempt these bodies from CGT is not a source of unfairness (Katz Commission, 1995; SARS, 2000). To examine these views in greater detail, the following statements are included in the correspondence analysis:

Statement 4: PBOs are not subject to full CGT exemption.

Statement 5: Recreational clubs are not subject to full CGT exemption.

2.4 Small businesses and job creation

Small businesses are frequently defined as the cornerstone of economies (Poterba, 1989; Manuel, 2010), leading to lobbying by emerging businesses for tax relief (Moore and Kerpen, 2001; Steyn, 2001; Conda, 2006:5-6). In this context, the South African Chamber of Business (SACOB) condemned CGT as having adverse implications for entrepreneurship and job creation. Citing France, Germany and Italy as examples, it was argued that the South African government's decision to levy CGT on small businesses was a possible contradiction of its stated objective of tax equity aimed at combating poverty (Poterba, 1989; Moore and Silva, 1995; Ededes, 2000; SACOB in Meyerowitz, Emsile & Davis, 2001).

According to SARS (2000; 2004), however, CGT should not affect the ability of small businesses and their proprietors to bear the tax load. Government maintains that material capital realisation by this sector is unlikely and that this is catered for by current partial exemptions (Meyerowitz et al., 2001; Meyerowitz et al., 2007; Manuel, 2010; s 8 of the Act; s 12E of the Act). Further, additional tax revenues attributable to CGT have, according to SARS (Manuel, 2008), formed part of the drive for subsequent and alternate tax relief (Manuel, 2001, 2008, 2009). In this context, the hypothesis that CGT may be a bona fide example of a disincentive to small business creation that is associated with a possible source of unfairness is specifically included in the correspondence analysis:

Statement 6: CGT may act as a disincentive to business start-ups.

In addition, the question whether or not relief in the form of CGT exemptions and the availability of deductible capital losses is perceived as adequate, and hence consistent with notions of tax fairness (Smith, 1776) is also addressed by the correspondence analysis:

Statement 7: Small business exemptions and deductibility of capital losses from capital gains are possible.

3 Method

A survey instrument (a correspondence table) was developed using an interpretive analysis of the prior literature (Bendixen, 1996; Maroun et al., 2011; Merkl-Davies, Brennan & Vourvachis, 2011). Each of the row (CGT-related statements) and column (fairness criteria) headings are derived from a detailed review of the professional and academic literature outlining the arguments for and against the levying of CGT on BEE schemes, clubs, PBOs and small businesses.

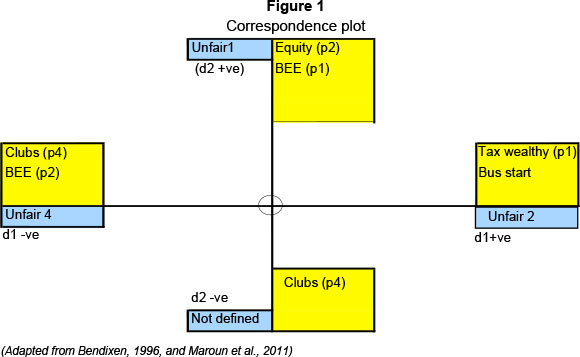

It should be noted that the researchers played an integral part in the development of the final correspondence table (Table 1). In particular, the selection of specific CGT effects was carried out by the researchers and is eclectic. Although this poses some threat to the validity of the research findings, the subjective, interpretive approach allowed the research to be more flexible and offered a fresh perspective on CGT. This was especially useful given the lack of prior interpretive or critical research in a South African tax setting (Creswell, 2009; O'Dwyer, Owen & Unerman, 2011). Further, "validity" and "reliability" should not be interpreted in terms of arms-length analysis of the subject matter and "generalisability", but rather in terms of providing a detailed, justified argument that allows the reader informed insight into the phenomenon being analysed (Creswell, 2009). To this end, it is important to note that the correspondence plot (Figure 1) simply aggregates the perceptions of the experts in the sample and "captures" these in a two-dimensional plot which is easy to interpret. At no time do we purport to "quantify" tax fairness or advance an "optimal solution". This is the realm of positivist research. Instead, the correspondence plot is used to inform the debate on the perceived fairness of certain aspects of CGT, grounded in critical corporate governance research and prior literature on CGT.

To ensure that the correspondence table was free from technical errors and/or ambiguities, the survey instrument was piloted and no material issues were noted. As discussed above, grounding the survey statement in the prior literature helped to mitigate possible researcher bias. The interpretation of results was also reviewed by each of the researchers for logic and coherence and earlier versions of this paper were presented to peers to ensure that the findings resonated with a broad group of informed readers.

3.1 Data collection and analysis

A purposeful selection technique, dictated by ease of access, was used to draw a sample of tax experts from a population comprising all registered taxpayers with an understanding of the Eighth Schedule to the Act. Only tax experts from several audit firms, COSATU, the National Treasury, SARS officials and tax academics with a thorough knowledge of CGT were selected, resulting in a sample size of 60.5 Barring issues of practicality, the technical nature of tax is such that carrying out a detailed review with people who are not sufficiently informed of the operation of the Eighth Schedule to the Act would have been nonsensical. Although the technique chosen carries the risk of bias, it ensured that only knowledgeable participants were engaged, thereby enhancing the quality of the findings (Brennan & Kelly, 2007; Creswell, 2009). In other words, the researchers were compelled to make a trade-off between the quality and the quantity of the responses. Nevertheless, although only experts were engaged, respondents were selected from a number of different organisations to ensure that a balanced reflection of CGT was obtained. This was especially important given that a number of experts may be holders of capital. To this end, roughly half of the respondents were drawn from the National Treasury, SARS and COSATU collectively. The remainder comprised tax practitioners and academics. As an additional safeguard, experts were reminded of the need for complete candour and objectivity when completing the correspondence table and were guaranteed complete anonymity (adapted from Brennan & Kelly, 2007; Creswell, 2009). Following this, the results of the correspondence analysis were contrasted with the debates reported in the prior literature. Finally, the choice and use of a correspondence analysis, including its statistical manipulations, was reviewed by an independent statistician.6

It must be stressed, however, that the perceived fairness of CGT is a complex and subjective issue not conducive to inferential testing dependent on large sample sizes where the samples consist of average taxpayers. This is an inherent characteristic of interpretive studies (Parker & Roffey, 1997; O'Dwyer et al., 2011) and not in itself a threat to validity and reliability, especially in this case, where participants require specific knowledge to provide an informed response. The final correspondence table completed by experts is presented as Table 1.

Respondents were required to mark with an "X" those statements (rows) which correspond with "absence of fairness criteria" (columns). Each "X" was assigned a value of one; a non-response was assigned a value of zero. In other words, where respondents agreed with the statement(s) and felt that the statement(s) was (were) associated with one or more unfairness characteristic, they marked the respective cell(s) with an "X". If they felt that a statement was appropriate or correct, but was not a material source of unfairness, the respective row would be left blank. The same is true if respondents disagreed with the respective statement. The chosen scale is nominal, with individual participants being asked to endorse each "category" by either agreeing or disagreeing. Together with the interpretive research style and normative nature of the findings, this means that measures of internal consistency, such as the Cronbach alpha, are not required.

To address the risk of the questionnaire eliciting negative responses due to its structure or result bias due to incorrect completion, respondents were provided with detailed instructtions on how to complete the correspondence table. In particular, they were advised that they could mark with an "X" as many or as few cells as they felt appropriate and that where they felt that there was no or little relationship between a row and column heading that the respective cell could be left blank. Further, respondents were reminded that there were no "correct" or "incorrect" answers, that their individual responses would be treated as confidential and that the research was being carried out for academic purposes only. Respondents were then left to complete the correspondence table in private.

A 7 row x 4 column correspondence table captured aggregated results. Correspondence analysis (principle component analysis per STATA) was used to generate a two-dimensional plot (Bendixen, 1996; Maroun et al., 2011) of the opinions of tax experts with respect to the fairness (according to Smith's (1776) canons) of the seven statements above (derived from the prior literature). For the purposes of the correspondence analysis, only the relationship between rows and columns is relevant. Neither the "sign" of any correlation nor the relationship between individual points plotted in the final two-dimensional space is, in itself, significant.7 Descriptive statistics are summarised in Table 2.

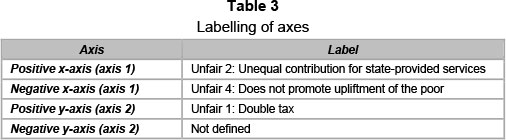

Row profiles and masses were used to calculate the inertia (variance) attributable to each cell in the contingency table (Table 1). The coordinates of the points-rows and points-columns, as well as the selection of axes (dimensions), illustrated in Figure 1, were developed by principal component analysis (Bendixen, 1996:15-21). The bi-plot details section (Table 2) was then used to define the respective axes according to Figure 1. In this regard, the axes, based on the four unfairness criteria, were determined by the coordinates of each unfairness criterion, the respective inertia of the unfairness criteria and their correlation coefficients with chosen axes. Unfairness criterion 3 showed both a low level of inertia and a weak correlation with two axes, and is not included in the final plot.

In summary, the correspondence analysis provides a simplified aggregation of the opinions of tax experts. The aim is not to "test" whether or not each statement is regarded as fair or unfair. Instead, the correspondence analysis highlights material correlations between statements and the unfairness criteria to inform further analysis by the researchers of certain of the prior literature. As such, the method neither oversimplifies the analysis through arbitrary "measurement" of perceived tax fairness nor provides cumbersome descriptions, which is a criticism of more interpretive studies (Merchant, 2008).

4 Results

The correspondence bi-plot (Figure 1) shows the relationships between statements (labelled P1 to P7) identified and the unfairness characteristics (labelled C1 to C4) derived in section 2. Results indicate significant dependencies, supporting the general contention: contrary to the South African government's stated policies, features of CGT are perceived as unfair. Table 2 indicates that the two-dimensional bi-plot (axes) had a retention value of 94 per cent, which is highly explanatory.

Correlations or associations between statements (plotted points) and the unfairness criteria (axes) are depicted by the sign of the statement and its correlation coefficient. The sign of a plotted point is not, in itself, synonymous with "unfairness" but rather an indication of its relationship with one of the axes (Bendixen, 1996). The significance of the paragraphs (inertia) and their relationship with specific axes (squared correlation) is explained in Table 2 and summarised in Figure 1. For the sake of clarity, Figure 1 summarises only those plotted points (statements) which made the highest inertia and correlation coefficient contributions. Bendixen (1996) recommends the use of a 0.3 correlation coefficient and 15 per cent inertial contribution for statements as the cut-off adopted for this analysis.

Statements p2 and p5 are positioned close to the positive y-axis, having correlation coefficients of 0.651 and 0.531 respectively, implying a strong correlation between p2 and p1 and the possibility that CGT may be a form of double tax. P1 is also correlated with the negative x-axis (r2=0.393), implying a correlation between the CGT consequences for BEE deals and a failure to uplift the poor. There was only a weak inertial contribution (8.5 per cent) by p2 to the x-axis. On the other hand, p4 was positioned close to the negative x-axis with a correlation coefficient of 0.666, implying a strong correlation between it and the failure to uplift the poor.

P1 and p6 were positioned close to the positive x-axis. The correlation coefficients were 0.962 and 0.836 respectively, implying a strong correlation between these statements and a failure to contribute fairly for state services. P1 and p6 made only weak inertial contributions to the y-axis (8 per cent and 9.5 per cent respectively) which, together with low correlation coefficients (0.009 and 0.164 respectively), implies little correlation between p1 and p6 and unfairness characteristic 1.

5 Discussion

Trust in government tax policies may be fostered through the use of powerful symbols and emotive slogans to legitimise the chosen policy superficially (Voster, 2000). In this context, the perceived fairness of a tax may be instrumental in winning the support of the body of taxpayers, either to ensure compliance or as a means of garnering votes (Voster, 2000; Farrar, 2011). In other words, tax policies that are used to create the impression of active reform may appeal to ideals of fairness where the true aim is retention of support by the political powers of the time (Watts & Zimmerman, 1979; Laughlin, 2007; Farrar, 2011).

Referring specifically to CGT in South Africa, government has argued that the tax plays an instrumental role in entrenching horizontal and vertical equity - much needed given the country's racially charged past and high unemployment (Katz Commission, 1995; COSATU, 2001; ANC, 2010). Contemporaneously, government has not lost sight of the importance of BEE, PBOs and small business schemes in poverty alleviation and has accordingly granted specific CGT relief in each case, as discussed in section 2. In doing so, the state has appealed to the notion of paying a fair quid pro quo for state services. It has also claimed that it has left taxpayers able to bear the tax load, an ideal derived from notions of horizontal and vertical equity and designed to foster an impression of a fair tax system (Vivian, 2006; Maroun et al, 2011).

The prior literature and correspondence analysis challenges this perception. Olivier (2007) and Arendse (2004a; 2004b) point to material shortcomings in the tax relief offered for BEE schemes, and Vivian (2006), Stein (2000) and Voster (2000) argue that CGT may amount to paying what amounts to double tax. These sentiments are highlighted by the correspondence analysis in which BEE tax relief and CGT's double tax potential are correlated with the unfairness characteristics. The correlation is also in line with the concerns regarding the suspension of the rollover provisions. The arguments that the provisions are at odds with the principle of consistent treatment of taxpayers and are being abused may have merit (Wood, 2001). The critics of CGT have pointed out, however, that little consideration has been given to the effect on emerging black business of taxing both income and realised capital gains (Wood, 2001; Scholtz, 2008).

With respect to the levying of CGT on PBOs and clubs, Mitchell (2006) and the SACC (2006) were concerned that, in spite of government's concessions, the potential of these organisations to uplift the poor would be undermined. Although the correspondence analysis did not consistently reveal materially high correlations between taxing PBOs and clubs and the unfairness criteria, the results do not dismiss the suspicions that CGT is driven by more than a simple desire to widen the tax base to uplift the poor. It was significant that, at the time when this research was conducted, SARS declined to make information on collection statistics pertaining to CGT - and how these funds were being used in combating poverty -available to the researchers. Finally, there was a reasonable correlation between the fact that PBOs and clubs are not fully exempt from CGT and the unfairness characteristics. The low inertial contribution could simply be indicative of the more limited role that these institutions play, relative to BEE schemes and small businesses. When it comes to the latter, government is adamant that the tax load effects will be negligible (Meyerowitz et al, 2007; Manuel, 2008; Manuel, 2010). Nevertheless, SACOB has challenged this assumption (Meyerowitz et al., 2001), a move supported by the correspondence analysis which identified at least some correlations between levying CGT on small business and the unfairness characteristics.

At the simplest level, the results of the literature review and correspondence analysis confirm the subjectivity and dynamic nature of the perceived fairness of CGT. On the other hand, the findings begin to suggest an alternative explanation: that there is inconsistency between government's stated objective of tax fairness (COSATU, 2001; Manuel, 2010) and the perceptions of tax experts, including those from the public sector. This could lend weight to the argument that tax legislation is used simply to create an illusion of fairness, possibly for the purpose of creating the impression of reform to win votes for political parties and/or to stifle opposition by taking the moral high ground (Voster, 2000). As such, prior scholarly work exploring how political agendas taint governance reforms is clearly relevant for scrutinising changes in tax policies.

6 Conclusion

In order for a tax system to be fair, it needs to meet certain fundamental requirements, as seminally explained by Smith (1776). The current research has focused on: firstly, the need to avoid double tax; secondly, the need to ensure that taxpayers pay a fair quid pro quo for state services; thirdly, the need to ensure that taxpayers are able to bear the tax load and, finally, given the South African context, the requirement that taxes should play a role in uplifting the disadvantaged (COSATU, 2001; Vivian, 2006).

In this context, three aspects of CGT were examined as primary examples of government's drive to tackle poverty in South Africa: the taxing of BEE schemes, the taxing of PBOs and clubs, and the taxing of small businesses. The correspondence analysis has shown that, in each of these areas, there may be potential sources of tax-based unfairness. The analysis has indicated that the levying of CGT on BEE schemes, clubs, PBOs and small businesses has, at least, some correlation with double tax, an unfair charge for state services, and a failure to adequately uplift the poor. The study has, therefore, demonstrated an inconsistency between the official policy of ensuring reform of the tax system based on the tenets of fairness (COSATU, 2001; Manuel, 2010) and the perceptions of taxpayers. This may suggest that fairness is a secondary consideration in the development of tax policy, which may primarily reflect political expediency.

The foregoing discussion and analysis of CGT in South Africa may be just such a case, where the underlying political intent of the tax is obscured by claims to be improving the fairness of the South African tax system (Voster, 2000; COSATU, 2011). This notion is supported by the findings of Laughlin (2007), Unerman and O'Dwyer (2004) and Power (1994), which suggest that reform is often tainted by the self-interest of powerful social players. While these research efforts have focused exclusively on the corporate governance environment, the findings of the current study suggest that an underlying powerful political rationale may be at play when it comes to South African tax reforms. The actual driving force for the introduction of CGT in South Africa can, therefore, be largely political and not the avowed morally incontestable argument which has been put forward, namely improving tax fairness.

Additional research will, however, be needed to conclude more definitively on the relevance of political power in tax-related reforms. For example, this paper has been limited by the small sample size of tax experts. Future research may consider testing the arguments raised in this paper with a broader group of stakeholders. Likewise, alternative views on CGT could be explored to provide a more comprehensive account of the rationale behind the tax. Is it possible, for instance, that CGT merely aligns the South African tax system with the systems of the country's major trading partners, thereby securing the credibility of local fiscal policy? More specifically, the role of standardising specific taxes as a strategy for their legitimisation (Suchman, 1995) and the way this strategy might be informed by the critical analysis outlined in this paper could prove insightful. Using the same critical analytical approach followed in this paper, it might, for example, be useful to examine the role of CGT in South Africa (and other jurisdictions) under the lens of Rawls's principles of justice. A more positivist approach could also be used to test the efficacy of CGT by examining whether the revenues collected from the tax are in excess of the costs of administration and the association (if any) between actual efficacy and perceived fairness. Integral to this is the need to interrogate the extent to which CGT is allowing government to achieve its social and economic objectives. The overriding upshot is that the debate on the fairness of particular taxes and tax policies needs to be considered with a much broader and critical research focus than is currently the case.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs L. Maddock for her editorial service and Professors K Sartorius and B Sartorius for assistance with the review of this paper and the relevant statistical manipulations.

References

AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS (ANC). 2010. ANC today. Available at: http://www.anc.org.za [accessed 2011-06-20]. [ Links ]

AHRENS, T., BECKER, A., BURNS, J., CHAPMAN, C.S., GRANLUND, M., HABERSAM, M., HANSEN, A., KHALIFA, R., MALMI, T., MENNICKEN, A., MIKES, A., PANOZZO, F., PIBER, M., QUATTRONE, P. & SCHEYTT, T. 2008. The future of interpretive accounting research-A polyphonic debate. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 19:840-866. [ Links ]

ARENDSE, J. 2004a. Solutions to the tax conundrum. Accountancy SA, October. ARENDSE, J. 2004b. BEE and tax: should there be a common ground? Accountancy SA, October. BENDIXEN, M. 1996. A practical guide to the use of correspondence analysis in marketing research. Marketing Research On-Line, 1:16-38. [ Links ]

BRENNAN, N. & KELLY, J. 2007. A study of whistleblowing among trainee auditors. The British Accounting Review, 39:61-87. [ Links ]

BRENNAN, N.M. & SOLOMON, J. 2008. Corporate governance, accountability and mechanisms of accountability: An overview. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 21:885-906. [ Links ]

BURCHELL, S., CLUBB, C., HOPWOOD, A., HUGHES, J. & NAHAPIET, J. 1980. The roles of accounting in organisations and society. Accounting, Organisations and Society, 5:5-27. [ Links ]

CANADA, J., KUHN, J.R. & SUTTON, S.G. 2008. Accidentally in the public interest: The perfect storm that yielded the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 19:987-1003. [ Links ]

CARRUTHERS, B.G. 1995. Accounting, ambiguity, and the new institutionalism. Accounting, Organisations and Society, 20:313-328. [ Links ]

COETZEE, K. 1998. Problems with equity in taxation with special emphasis on the South African situation. In: KH Kleynhans ed. South African Accounting Association Biennial Conference, 9 July 1998, Johannesburg. Johannesburg: South African Accounting Association. [ Links ]

COETSEE, D. & STEGMANN, N. 2012. A profile of accounting research in South African accounting journals. Meditari Accountancy Research, 20:92-112. [ Links ]

CONGRESS OF SOUTH AFRICAN TRADE UNIONS (COSATU). 2001. Capital gains tax: Presentation to the portfolio committee on finance. Available at: http://www.cosatu.org.za/docs/1999/progtax.htm [accessed 2006-03-10]. [ Links ]

CONGRESS OF SOUTH AFRICAN TRADE UNIONS (COSATU). 2011. COSATU NW is giving a strong warning to the new mayors. Available at: http://www.cosatu.org.za [accessed 2013-01-03]. [ Links ]

CONDA, C. 2006. The best cap-gains tax rate is zero. Available at: http://www.freedomworks.org/informed/issues_template.php?issue_id=2524 [accessed 2006-03-10]. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J. 2009. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.) London: Sage. [ Links ]

DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE. 2011. 2011 Election campaign. Available at: http://www.da.org.za/campaigns.htm?action=view-page&category=9075 [accessed on 2012-01-09]. [ Links ]

DYL, E. 1977. Capital gains tax and year end stock market behaviour. The Journal of Finance, 32:1. [ Links ]

ENSOR, L. 2001a. No concessions yet for restructurings. Business Day, 12 February. [ Links ]

ENSOR, L. 2001b. Call to exclude share-based deals from capital gains tax. Business Day, 10 February. [ Links ]

EDEDES, J. 2000. Capital gains tax. Financial Mail, 15 April. [ Links ]

FARRAR, J. 2011. Tax fairness in Canadian government budgets: How fair is fair'? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 22:365-375. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, M. 1977. Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York: Vintage Books. HARRISON, P. 2001. Do we need a new tax? Business Day, 12 February. [ Links ]

HAYEK, F. 1960. The constitution of liberty. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

HUMPHREY, C. 2008. Auditing research: A review across the disciplinary divide. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 21:170-203. [ Links ]

INCOME TAX ACT 58 of 1962 (as amended). In: SAICA Legislation handbook 2006/2007. Durban: LexisNexis Butterworths, 2012. [ Links ]

KAPLAN, S.E. & RULAND, R.G. 1991. Positive theory, rationality and accounting regulation. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 2:361-374. [ Links ]

KATZ COMMISSION. 1995. Third interim report of the commission of inquiry into certain aspects of the tax structure of South Africa. 1995. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

KHALIFA, R., SHARMA, N., HUMPHREY, C. & ROBSON, K. 2007. Discourse and audit change: Transformations in methodology in the professional audit field. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 20:825-854. [ Links ]

LAUGHLIN, R. 1995. Empirical research in accounting: Alternative approaches and a case for "middlerange" thinking. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 8:63-87. [ Links ]

LAUGHLIN, R. 2007. Critical reflections on research approaches, accounting regulation and the regulation of accounting. The British Accounting Review, 39:271-289. [ Links ]

LLEWELYN, S. 1996. Theories for theorists or theories for practice? Liberating academic accounting research? Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 9:112-117. [ Links ]

LLEWELYN, S. 2003. What counts as "theory" in qualitative management and accounting research? Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 16:662-708. [ Links ]

MALSCH, B. & GENDRON, Y. 2011. Reining in auditors: On the dynamics of power surrounding an "innovation" in the regulatory space. Accounting, Organisations and Society, 36:456-476. [ Links ]

MANUEL, T. 2001. Budget speech (2005). Available at: http://www.treasuary.gov.za [accessed 2006-11-11]. [ Links ]

MANUEL, T. 2006. Budget speech (2006). Available at: http://www.treasuary.gov.za [accessed 2006-11-11]. [ Links ]

MANUEL, T. 2007. Budget speech (2007). Available at: http://www.treasuary.gov.za [accessed 2009-06-15]. [ Links ]

MANUEL, T. 2008. Budget speech (2008). Available at: http://www.treasuary.gov.za [accessed 2009-06-15]. [ Links ]

MANUEL, T. 2009. Budget speech (2009). Availableat: http://www.treasuary.gov.za [accessed 2010-06-11]. [ Links ]

MANUEL, T. 2010. Budget speech (2010). Available at: http://www.treasuary.gov.za [accessed 2011-05-14]. [ Links ]

MARGO COMMISSION. 1986. Report of the commission of inquiry into the tax structure of the Republic of South Africa. 1986. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

MAROUN, W. 2012. Interpretive and critical research: Methodological blasphemy! African Journal of Business Management, 6:1-6. [ Links ]

MAROUN, W., TURNER, M. & SARTORIUS, K. 2011. Does capital gains tax add to or detract from the fairness of the South African tax system? South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 14:436-448. [ Links ]

MARRIOTT, L. 2010. Power and ideas: The development of retirement savings taxation in Australasia. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 21(7):597-608. [ Links ]

MERCHANT, K.A. 2008. Why interdisciplinary accounting research tends not to impact most North American academic accountants. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 19:901-908. [ Links ]

MERKL-DAVIES, D., BRENNAN, N. & VOURVACHIS, P. 2011. Text analysis methodologies in corporate narrative reporting research. 23rd CSEAR International Colloquium. St Andrews, United Kingdom. [ Links ]

MEYER, J.W. & ROWAN, B. 1977. Institutionalized oragnisations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83:340-363. [ Links ]

MEYEROWITZ, D., EMSILE, T. & DAVIS, D. 2001. Capital gains tax. The Taxpayer, 50:4. [ Links ]

MEYEROWITZ, D., EMSILE, T. & DAVIS, D. 2007. The 2007 budget. The Taxpayer, 56:2. [ Links ]

MITCHELL, K. 2006. Off side-recreational clubs. Tax Planning, 20:6. [ Links ]

MITCHELL, A. & SIKKA, P. 2004. Accountability of the accountancy bodies: The peculiarities of a British accountancy body. The British Accounting Review, 36:395-414. [ Links ]

MONTESQUIEU. 1748. The spirit of the laws. London: The Hafner Library of Classics, 1949 (1975 reprint). MOORE, S. & KERPEN, P. 2001. A capital gains tax cut: The key to economic recovery. Institute for Policy Innovation, Report Number 164, Available at: http://www.ipi.org/ipi/IPIPublications.nsf/PublicationLookupFullText/EC18ED9B8007A064862 56AE2002BA80D [accessed 2007-10-12]. [ Links ]

MOORE, S. & SILVA, J. 1995. The ABCs of capital gains tax. Cato Institute: Policy Analysis, No. 242, October. Available at: https://cato.org/pub_display.php?pub_id=1101&print=Y&full=1 [accessed 2007-07-09]. [ Links ]

O'DWYER, B., OWEN, D. & UNERMAN, J. 2011. Seeking legitimacy for new assurance forms: The case of assurance on sustainability reporting. Accounting, Organisations and Society, 36:31-52. [ Links ]

OLIVIER, L. 2007. Determining a taxable capital gain or assessed capital loss: Some problems. Meditari Accountancy Research, 15(1):35-50. [ Links ]

PARKER, L. & ROFFEY, B. 1997. Methodological themes. Back to the drawing board: Revisiting grounded theory and the everyday accountant's and manager's reality. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 10:212-247. [ Links ]

POTERBA, J. 1989. Venture capital and capital gains tax. Available at: http://nber15.nber.org/papers/w2832.pdf?new_window=1 [accessed: 2007-11-01]. POWER, M.K. 1994. The audit explosion. London: Demos. [ Links ]

RICARDO, D. 1817. The principles of political economy and taxation. London: Murry, 1984. Available at: http://www.econlib.org/LIBRARY/Ricardo/ricP.html [accessed on 2007-07-01]. [ Links ]

ROBERTS, S. 2006. Capital gains tax-Advantages & disadvantages of capital gains tax cut. Idia Finance and Investment Guide. Available at: http://finance.indiamart.com/taxation/advantages_disadvantages_capitalgains.html [accessed: 2006-11-11]. [ Links ]

SCHOLTZ, W. 2008. Treasury could put a halt to BEE deals. MoneywebTax. Available at: www.moneywebtax.co.za/moneywebtax/view/moneywebtax/en/page1 [accessed: 2011-08-01]. SIKKA, P., PUXTY, A., WILLMOTT, H. & COOPER, C. 1998. The impossibility of eliminating the expectations gap: Some theory and evidence. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 9:299-330. SMITH, A. 1776. An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd. [ Links ]

SMITH-LACROIX, J.-H., DUROCHER, S. & GENDRON, Y. 2012. The erosion of jurisdiction: Auditing in a market value accounting regime. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 23:36-53. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN COUNCIL OF CHURCHES. 2006. Submission to the portfolio committee on finance. Available at: http://www.sacc-ct.org.za/rlab2006.html [accessed: 2007-05-31]. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN REVENUE SERVICES (SARS). 2000. Guide to capital gains tax. Available at: http://www.treasuary.gov.za/documents/budget/2000/cgt/cgt.pdf [accessed 2006-11-11]. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN REVENUE SERVICES (SARS). 2004. Budget review (2004). Available at: http://www.treasuary.gov.za [accessed 2007-11-12]. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN REVENUE SERVICES (SARS). 2006. Budget review (2006). Available at: http://www.treasuary.gov.za [accessed 2007-11-12]. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN REVENUE SERVICES (SARS). 2008. Budget review (2008). Available at: http://www.treasuary.gov.za [accessed 2008-10-12]. [ Links ]

SOX. 2002. Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Pub. L. 107-204, 116 Stat. 745. SOX. United States of America. [ Links ]

SUCHMAN, M.C. 1995. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20:571-610. [ Links ]

STEIN, M. 2000. Capital gains tax. Income Tax Reporter, 39:3. [ Links ]

STEYN, T. 2001. SARS stands firm on capital gains tax. Business Day, 11 May. [ Links ]

STIGLINGH, M., KOEKEMOER, A.D. & WILCOCKS, J. 2011. SILKE: South African income tax 2011. South Africa: LexisNexis. [ Links ]

SY, A. & TINKER, T. 2008. Sarbanes-Oxley: An endangered species? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 19:927-930. [ Links ]

TILLEMA, S. & TER BOGT, H.J. 2010. Performance auditing: Improving the quality of political and democratic processes? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 21:754-769. [ Links ]

TREMBLAY, M.-S. & GENDRON, Y. 2011. Governance prescriptions under trial: On the interplay between the logics of resistance and compliance in audit committees. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 22: 259-272. [ Links ]

UNERMAN, J. & O'DWYER, B. 2004. Enron, WorldCom, Andersen et al.: A challenge to modernity. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 15:971-993. [ Links ]

VIVIAN, R .2006. Equality and personal income tax-The classical economist and the Katz Commission. South African Journal of Economics, 74:1. [ Links ]

VOSTER, D. 2000. Capital gains tax-A discredited tax. Tax planning, 14:6. [ Links ]

WATTS, R. & ZIMMERMAN, J. 1979. The demand for and supply of accounting theories: The market for excuses. The Accounting Review, 54:273-305. [ Links ]

WOOD, S. 2001. Brace for the blade. The Financial Mail, August. [ Links ]

Accepted: June 2013

Endnotes

1 Strictly, capital gains tax (CGT) is not a separate tax in South Africa. CGT is a tax on the disposal of certain capital assets that is calculated in terms of the provisions of the Eighth Schedule and, once calculated, is incorporated into the normal income tax (Stinglingh et al, 2011). In the interests of brevity, however, this paper refers simply to CGT.

2 This is not to say that the economic role of tax is irrelevant. Government requires tax revenues to fund social and economic objectives. The aim of this research is not, however, to examine the economic case for CGT in detail but rather to concentrate on the relevance of political discourse.

3 Instead of relying on the doctrines of Smith (1776), Kantian, social justice, or legitimacy theories could have been used to study CGT in more detail. Smith (1776), however, provides a seminal account that deals directly with capital-based taxes (Vivian, 2006).

4 Smith's (1776) tax canon highlights four fairness "attributes". Firstly, a tax charged on both income and capital is tantamount to a double tax and is an injustice (first "unfairness criterion" in the correspondence analysis). Secondly, tax should represent a fair quid pro quo for state services with only amounts earned under the protection of the state being taxed (second "unfairness criterion" in the correspondence analysis). Thirdly, a balance must be struck between the state's quest for revenue and the taxpayer's right to bear only a reasonable tax load. In other words, taxpayers should, post tax, be able to sustain themselves (Vivian, 2006:84; Smith, 1776; Montesquieu, 1748:XIII.1) (third "unfairness criterion" in the correspondence analysis). Finally, a progressive system may be less desirable than a proportional one (Vivian, 2006).

This research concentrates on the first, second and third criteria. South Africa has historically used a proportionate tax system, unchanged by the introduction of CGT. The fourth criterion was excluded by the correspondence analysis (section 3). In addition, an exploration of the merits of a source versus residency basis of taxation is a complex issue beyond the scope of this paper. As a result, the second criterion is dealt with only in the sense of paying a fair share for state services. Finally, to reflect the South African context of high levels of unemployment and emphasis on poverty alleviation (Manuel, 2010), "upliftment of the poor" has been specifically added to the correspondence analysis.

5 It must be stressed that the purpose of this research is to summarise perceptions of individual respondents and that detailed statements explaining why a particular row heading is unfair are, therefore, not included. This is consistent with the fact that the paper's intention was not to "measure" the unfairness of CGT and with the desire on the part of the researcher to avoid influencing the perceptions of respondents.

6 During the data collection process, no concerns regarding the clarity of the correspondence table or ethical issues were noted.

7 Variations of the method used in this paper were also presented at the British Accounting and Finance Association Conference (2011), the International Corporate Governance Conference (2012) and the Africa Leads Conference (2012) to ensure its appropriateness.