Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versão On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.17 no.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

ARTICLES

Project governance: "schools of thought"

Michiel C Bekker

Graduate School of Technology Management, University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

The terminology, definition and context of project governance have become a focal subject for research and discussions in project management literature. This article reviews literature on the subject of project governance and categorises the arguments into three schools of thought namely the single-firm school, multi-firm school and large capital governance school. The single-firm school is concerned with governance principles related to intra-organisational projects and practice these principles at a technical level. The multifirm school addresses the governance principles concerned with two of more organisations participating on a contractual basis on the same project and focuses its governance efforts at the technical and strategic level. The large capital school considers projects as temporary organisations, forming their own entity and establishing governance principles at an institutional level. From these schools of thought it can be concluded that the definition of project governance is a function of stakeholder complexity and functional positioning in the organisation. It is also evident that further research is required to incorporate other governance variables and related theories such as transaction theory, social networks and agency theory. The development of project governance frameworks should also consider the complexity of projects spanning across international companies, across country borders and incorporating different value systems, legal systems, corporate governance guidelines, religions and business practices.

Key words: project governance, governance of projects, meta-governance, governance through projects, project management.

JEL: L890

1 Introduction

Since the late 1990s the term project governance has attracted much attention and debate in the project literature. The quest to define and apply project governance is fuelled by the growing frustration of large capital project failure (Flyvbjerg, Bruzelius & Rothengatter, 2003:12-21; Miller & Lessard, 2000:14) and the realisation that project management at a technical and operational level should be complemented and supported at strategic and institutional management levels (Klakegg & Artto, 2008). The incorporation of governance into the project field reflects a widening of focus away from the day-to-day technical, operational and supporting activities that need to be fulfilled to ensure the delivery of project outcomes. Addressing governance also acknowledges the role projects play in the overall organisational performance and the interactions between the multiple actors responsible- for the various project and organisational activities (Sanderson, 2012:432). Given this increased attention and intense debate, providing a state-of-the art overview of the literature is timely and appropriate.

This literature review was conducted through topical searches on project governance related articles and documents on Google Scholar, and specifically publications in the International Journal of Project Management and the Project Management Journal.

In reviewing the literature and participating in various workshops on project governance, it has become clear that there is still no commonly understood and agreed upon definition for project governance. However, from the literature some tendencies towards preferred points of departure for constructing project governance definitions and constructs are emerging. These points of departure are linked to the various researchers' and authors' industry of application, type of projects, their understanding of the meaning of governance, the type of organisation and the functional positioning of projects in various organisations. Given the uncertainty surrounding the definition, and contextualisation of project governance the question remains whether the current available information and literature on the topic can be categorised and funnelled into common 'schools of thought'?

The aims of this paper are threefold. First, an in depth literature review on project governance and the categorisation thereof was conducted with the specific objective of extracting the various definitions and contexts. Second, the literature findings were categorised in various 'schools of thought'. The alignment of project governance principles with the overall corporate governance of the project owner organisation remains important with the third part of the paper explaining this important linkage. Lastly, the paper provides a conclusion and recommendations for future research in the field of project governance.

2 Categorisation of project governance concepts

In the project governance literature, Ruuska, Ahola, Artto, Locatelli and Mancini (2011: 650) identified three main categories of project governance based on the variety and level of stakeholder involvement. The first category of literature focuses on analysing a single firm's governance scheme with its multiple projects. The single firm is the ultimate decision-making authority and has full control over policies, processes and activities of projects. The second category considers multi-firm projects where various companies engage in contractual agreements. In this category each participating firm has its own vested interests in the project and the main focus of the governance structure is the protection of intellectual property. The third category considers projects as hybrid or network like structures involving multiple interconnected actors relying on the presence of one supreme hierarchical authority, almost always the lead sponsor or underwriting firm. This form of project governance is analogous to the lead organisation-governed networks as referred to by Provan and Kenis (2008:235). These projects can involve a diverse accumu- lation of actors with, quite often, opposing interests and agendas towards the management, as well as outcome of the project.

In a second categorisation of projects, Morris and Geraldi (2011:20-23) argued that the management of projects in institutional contexts could be viewed at three functional levels. These levels and their contexts are:

Level 1: Technical - operational and delivery orientated with the focus on the tools to be used, practices and day-to-day execution and control of project activities.

Level 2: Strategic - managing projects as organisational, holistic entities, expanding the domain to include their front-end development and definition and with a concern for value and effectiveness. This level ensures alignment with the sponsor's objectives, leadership, contracting strategy, manpower and influencing stakeholders.

Level 3: Institutional - managing projects in the macro-economic environment incorporating political, societal, socio-economical, environmental and statutory expectations and requirements.

Even though the main difference between the categorisation of projects by Ruuska et al. (2011:650) and Morris and Geraldi (2011:20-23) lies within the type of project versus functional approach, some common governance elements are observed. First, the single firm governance scheme focuses more internally conducting governance at a technical level where project control and monitoring activities are exercised. Next, multi-firm projects' governance scheme is concerned with the relationship between contracting parties and operates at a technical and strategic levelFinally, the category of hybrid or network type projects relies on institutional arrangements to ensure some form of governance. The third and last category is most commonly found in stand-alone, large capital projects with multiple, inter-organisational and inter-governmental arrangements. With limited reference to specific project characteristics and emphasis on relationships and contracts among internal and external actors it seems as if project governance in this category is more concerned with stakeholder rather than project complexity.

The categorisation of these commonalities forms the basis of the project governance 'schools of thought', which are discussed below.

3 'Schools of thought'

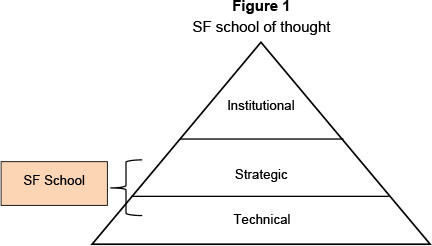

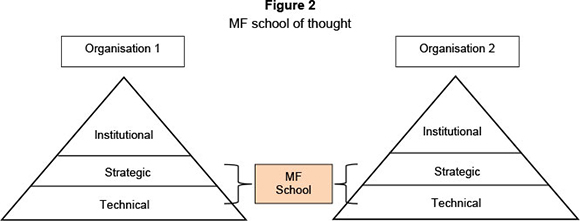

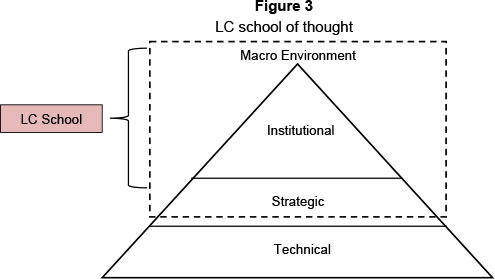

The three project governance 'schools of thought' are based on a combination of the categorisation identified by Ruuska et al. (2011: 650) and the functional organisational positioning of project governance (Morris & Geraldi, 2011:20-23). The terminology for the single -and multi-firm projects is retained while the large, standalone projects are categorised into a large capital project school. The functional differences are incorporated into these schools and graphically explained in the paragraphs that follow. The three governance schools are:

• Single firm (SF) governance school.

• Multi-firm (MF) governance school.

• Large capital (LC) governance school.

Even though approaches to project governance are categorised into the above schools of thought, it does not mean that all aspects of- each category are mutually exclusive. There are potential areas of overlapping of concepts, especially between the MF and LC schools which will be highlighted below in the discussion of each school of thought.

3.1 Single firm (SF) governance school

The definition and application of project governance in the SF school is driven by projects, or programmes, within a single, autonomous company. Due to the internal focus, SF school practitioners are often IT companies and organisations more concerned with their internal projects with no, or minimal, external client engagement. Projects in these companies are focused towards pursuing improvement of internal organisational performance; they are aligned with organisational strategy, return on investment, adherence to internal policies and procedures as well as protection of company information. Due to its top-down nature, the SF school view project governance at a strategic and technical level (Figure 1).

Marnewick and Labuschagne (2011:668) found IT project governance concerns selecting the right internal projects and that they are implemented as per company methodologies and standards. Bouraad (2010:75) seconds IT project and portfolio governance to the operational manager level and argues that, although necessary, the awareness of the importance and practical application of governance at this level is insufficient in researched organisations. The gap between IT governance and its position within project governance is also emphasised by Sharma, Stone and Ekinci (2009:29). However,- the importance of understanding and formalising of IT project governance will increase in the future due to the incorporation of IT governance into corporate governance guidelines such as King 3 (Institute of Directors South Africa, 2009).

Further SF school thinking is also evidenced in the APM Guide of Governance of Project Management (APM, 2004) where the focus is on 'looking over the shoulder' of the project manager to ensure compliance to good project management practices. In this respect concepts such as 'control', 'manage', 'supervise', 'monitor', 'strategic fit', 'resourcing', are often found in SF governance school thinking. Shifting focus to a more technical level, the APM Guide to the Governance Aspects of Project Sponsors (2009) is concerned with giving guidance to project sponsors on how to conduct their governance activities on the organisational projects (Crawford, Cooke-Davies, Hobbs, Labuschagne, Remington & Chen, 2008).

Currently text books focus mostly on the SF school suggesting that governance models should link governance at different project-related levels such as project, program and portfolio management (Renz, 2007; Oaks, 2008; Garland, 2009; Müller, 2009).

In the SF school, the value of the project is of secondary concern. This means that large capital projects, of significant monetary value, could also reside under the SF school if such projects are under the single control, influence and authority of the said firm.

3.2 Multi-firm (MF) governance school

Also functioning at the strategic and technical levels the MF governance school concentrates- on the contractual relationships among different firms participating in a single, or in multiple projects (Figure 2). Participating firms could be represented from all spheres of society including profit, non-profit or government entities. Winch (1989:331) argued that despite the existence of three influential perspectives in project management namely; socio-technical, organisation and environment, as well as project management practices, they contain no formal framework for analysing and managing the inevitable differences in interest between the different coalition firms who are members of the project. This observation can be traced to the investigation of transaction cost theory (Williamson, 1981:548, 573) which suggests mechanisms to analyse differences in interest between exchanging actors. In order to clarify the mutual interest of firms in knowledge and company intelligence Winch (2001:803-804) developed the horizontal transaction governance concept covering employment relations and supply chain dynamics across participating firms.

Bosch-Sijtsema & Postma, (2010), Pemsel & Müller (2012) and Kannabiran & Pandyan (2010) investigated the governance factors which enable knowledge transfer in interorganisational development projects. With various parties participating in day-to-day project activities across organisational boundaries some participants will be exposed to sensitive information and know-how of the participating coalition firms. In their research Bosch-Sijtsema & Postma (2010:605) found that a mixture of mutual trust and formal contracts serve as governance mechanisms across- organisational boundaries. This finding complements previous research in corporate innovation projects where it was found that firms focusing on mutually gaining access to the knowledge bases of their partners can develop a stable relationship based on mutual trust as their main governing mechanism (Bosch-Sijtsema & Postma, 2009:69).

Supporting the application of project governance at a strategic and technical level Abu Hasim, Kajewski and Trgunarsyah (2011:1930) highlighted the importance of proper protocol and transparency when handling commercial contracts and procurement across the client and participating consultants and contractors. Finally, Ruuska et al. (2011:650) listed the following key elements of project governance to be considered among multi-firm projects:

• Contracts between involved actors;

• How procurement is organised and carried out;

• How networks of suppliers are managed by project actors;

• How risks are managed and shared by project actors;

• How work is monitored and controlled during the project life cycle;

• How the project actors collaborate and develop practices, and;

• How communication between project actors is organised.

Literature supporting the MF school often refer to governance activities with concepts such as 'relationships', 'agreement', 'contracts', 'collaboration', 'protection'.

3.3 Large capital (LC) governance school

The LC school tends to view projects as goal-directed temporary organisations which have to define appropriate governance frameworks within which project decisions can be made (Bekker & Steyn, 2009). Sanderson (2012:440) emphasizes the difference between governance and governing. The former is explained as a form of organi- sation that can be consciously designed ex ante, again highlighting the conceptual view of large projects being considered as temporary organisations with their own governance frameworks. Governing is concerned with the act of performing governance activities. The intrinsic complexity of many large capital projects, whether private, public or public-private-partnership projects, lies in their cosmopolitan composition of different contracting companies from different organisations often working across country boundaries. Ruuska et al. (2011: 657) emphasise this stakeholder complexity by arguing that large projects continuously face the challenge of governing a project's internal complex supply chain of multiple, multinational firms while simultaneously governing the network of external actors. Large project performances are affected by complex institutional environments, and by the underlying business network of organisations. Due to this complex integration of various internal and external stakeholders the conception and context of project governance and the underlying mechanisms of coordination should shift from simplistic governance carried out by either the price mechanism or administrative functions towards mechanisms that emphasize relationships and self-regulation in such hybrid networks. In the LC school the focus shifts from contractual and strategic agreements to higher level, institutional issues that interact with the external/ macro environment (Figure 3).

Within the LC governance school the emphasis is on creating an environment, shielded from external environmental, political and strategic influences, within which the activities of project management can prosper. A central theme is 'decision-making', as opposed to management and controlling. These complex mechanisms and interactions are commonly found in (international) public and public-private-partnership (PPP) projects. As part of project governance, Abednego and Ogunlana (2006) studied the complexity of allocating risks in PPP projects. Yilin, Yaling, Ling and Zhe (2008) argued that by elevating project governance to a more strategic level in public projects the foundation is laid for continuous improvement during project execution. Researching various public projects Klakegg, Williams, Magnussen and Glasspool (2008:S30), concluded that a project governance framework should consist of an authoritative, organised structure within the sponsoring institution, comprising of processes and rules to ensure that projects meet their purpose. Williams et al. (2010) took the process approach further and concludes that the gatereview process as a quality control mechanism should form an integral part of the governance framework of public projects. This finding supports the view from Samset, Berg and Klakegg (2006) and Christensen (2009) who refer to the strategic management of the early phases of major public project as 'front-end governance'. In their view the establishment of proper governance principles, processes, guidelines and decision-criteria during the early stages of any large project are paramount for potential project success. Lastly Winch (2001:800) refers to the governance of the project process as the 'process of the progressive reduction of uncertainty through time'.

Moving beyond project governance at a strategic level Koch and Buser (2006:551) developed the concept of meta-governance for PPPs. Deployed at a macro level, meta-governance instruments includes soft laws, incentives, guidelines, brokering activities and legal mechanisms in the forms of laws and contracting.

Key concepts found in the LC governance school literature are 'politics', 'policy', 'principles', 'guidelines', 'decision-making', 'socio-economics', 'front-end', 'external stakeholder interest' and 'ethics'.

3.4 Categorisation of project governance 'schools of thought'

Even though the term project governance is commonly used amongst project practitioners, various other related terms appear in literature. These terms include 'governance of project management', 'governance of projects', 'governance regime', 'governance through projects', etc. A list of terms, definitions and their context are provided in Table 1 with the categorisation into schools of thought added.

In the first column the various terms used in literature are listed with the references indicated in the fourth column. The second column depicts the attempted definition by each resource. It must be noted that in all cases the definitions were derived from the arguments contained in the literature with exception of the Bekker and Steyn (2009) definition which was concluded from a Delphi study. Unfortunately not all the literature concerned with project governance proposed definitions for the terms. However, some context and key words were provided which are listed across the appropriate reference in the third column. Given the key words and context each resource was then categorised as per the defined 'schools of thought' namely SF, MF and LC.

As an example the first row contains the term "governance of project management" which is listed by two sources namely the APM (2004) and PRINCE2 TM (2009:265). The first reference provides a definition that links project activities with corporate governance while the second reference is more concerned with portfolio management and organisational objectives. Both references contain key words such as 'portfolio direction', sponsorship', project management effectiveness and efficiency', 'disclosure and reporting', 'controlling' and 'monitoring'. Given these key words, context and definition the reference is categorised with the SF governance school of thought.

Apart from the categorisation of projects the linkage and alignment with corporate governance seems undisputable. Even though this deduction seems logical, the alignment with corporate governance as overarching, and even dictating theme, can cause further complexity.

4 Conclusion

The definition, framing and practice of project governance can be influenced by the corporate environment within which the project is managed. The definition of project governance varies from a technical level of controlling, monitoring and complying to the strategic levels of management and coordinating and finally the institutional level of guidance, decision-making and responsible citizenship. The differences in governance approaches are driven more by stakeholder complexity rather than project complexity. In this study three project governance schools of thought namely SF, MF and LC, were formulated and various project governance definitions found in literature were categorised in the three schools.

Projects initiated and managed within a single firm form part of the SF school and are mostly governed by methods, controls, procedures, processes and project governance frameworks internal to the company. These internal governance frameworks are aligned with the corporate governance framework of the respective company but normally operate at a technical level to ensure compliance with the internal processes.

A second form of project governance is found among two or more organisations engaging in a contractual relationship and is referred to as the MF school. With these relationships the participating organisations gain access to each other's intellectual property, knowledge and information and therefore some form of project governance framework needs to be designed and applied to protect organisational and mutual interests.

The LC school of project governance is found in large capital projects. The LC school consist of projects that are often standalone, temporary organisations with various internal and external stakeholders. Large capital projects include infrastructure PPP projects and often have project life-cycle spanning over many years, across country boundaries involving various participating contractors, consultants and organisations from different countries. The LC school view project governance at a strategic and even institutional level whereas the total project is seen as a legal entity subject to a governance framework not necessarily defined by the corporate governance framework of the sponsor.

Project governance is multi-dimensional and the content of a project governance framework is very much dependent on the type of project as well as the number and variety of shareholders and stakeholders involved.

5 Recommendations for future research

Corporate governance is a specialist field with the research done mostly by individuals or teams with an economic, accounting or legal background. Thus far it appears as if research in project governance is conducted mostly by scholars with a project management background. In order to merge or align project and corporate governance, project management scholars need to have a proper understanding of the philosophy, definition and mechanisms around governance and corporate governance as well as the different approaches followed by different countries. Even though Winch (2001: 800) and Williams (1981:548) make reference to the role of transaction cost theory in the context of governance, the overall agency problem with associated agency cost in terms of the governance of projects, needs to be- further investigated in the project context. As with corporate governance the incorporation of governance in the project environment should take cognisance of the broader set of external forces across nations that influence the structure of the governance system. Hoetker and Mellewigt (2009:1025) refer to relational and formal governance mechanisms that should be considered when reviewing the transaction type. According to Larcker and Tayan (2011:8-10), these include the efficiency of local capital markets, legal tradition, reliability of accounting standards, regulatory enforcement, and societal and cultural values. These forces serve as external management, disciplining and controlling mechanisms that will determine and regulate managerial behaviour. There are no universally agreed-upon standards that determine good governance which makes the formalisation of a project governance framework for especially large, multi-national projects extremely complicated (complex?).

The development of project governance frameworks for projects spanning across national companies, across country borders and incorporating different value systems, legal systems, corporate governance guidelines, religions and business practices opens a wide area for further research. With no universally defined, globally acceptable corporate governance framework available, the quest for a standard project governance framework, aligned with corporate governance, remains active.

With project governance being a merged concept of project management and corporate governance, it would be beneficial to form coalition research teams to ensure cross-pollination of both fields of expertise.

References

ABEDNEGO, M.P. & OGUNLANA, S.O. 2006. Good project governance for proper risk allocation in public-private partnerships in Indonesia. International Journal of Project Management, 24:622-634. [ Links ]

ABU HASSIM, A., KAJEWSKI, S. & TRIGUNARSYAH, B. 2011. The importance of project governance framework in project procurement planning. Procedia Engineering, 14:1929-1937. [ Links ]

ASSOCIATION FOR PROJECT MANAGEMENT (APM). 2004. A guide to governance of project management. [ Links ]

ASSOCIATION FOR PROJECT MANAGEMENT (APM). 2009. A guide to the governance aspects of project sponsorship. [ Links ]

BEKKER, M.C., & STEYN, H. 2009. Defining 'project governance" for large capital project. South African Journal for Industrial Engineering, November 2009, 20(2):81-92. [ Links ]

BOUAARD, F. 2010. IT project portfolio governance: the emerging operation manager. Project Management Journal, 41(5):74-86. [ Links ]

BOSCH-SIJTSEMA, P.M. & POSTMA, T.J.B.M. 2009. Cooperative innovative projects: capabilities and governance mechanisms. The Journal of Product Innovation Management, 26(1):58-70. [ Links ]

BOSCH-SIJTSEMA, P.M. & POSTMA, T.J.B.M. 2010. Governance factors enabling knowledge transfer in interorganisational development projects. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 22(5):593-608. [ Links ]

CHRISTENSEN, T., 2009. The Norwegian front-end governance regime of major public projects - a theoretical based analysis. NTNU Concept Report, Nr 23, 11. [ Links ]

CRAWFORD, L., COOKE-DAVIES, T. HOBBS, B., LABUSCHAGNE, L., REMINGTON, K., & CHEN, P. 2008. Governance and support in the sponsoring of projects and programs. Project Management Journal, 39(Supplement):S43-S55. [ Links ]

FLYVBJERG, B., BRUZELIUS, N., & ROTHENGATTER, W., 2003, Megaprojects and risk: An anatomy of ambition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

GARLAND, R. 2009. Project governance: a practical guide to effective project decision making. Kogan Page Limited: London, England. [ Links ]

HOETKAR, G. & MELLEWIGT, T. 2009. Choice and performance of governance mechanisms: matching alliance governance to asset type. Strategic Management Journal, 30(10):1025-1044. [ Links ]

INSTITUTE OF DIRECTORS IN SOUTH AFRICA. 2009. King 3 code for corporate governance for South Africa, 2009, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

KANNABIRAN, G. & PANDYAN, C. 2010. Enabling role of governance in strategizing and implementing KM. Journal of Knowledge Management, 14(3):335-347. [ Links ]

KLAKEGG, O.J. & ARTTO, K. 2008. Integrated management framework for the governance of multiple projects. 22ndIPMA World Congress, Rome, Italy, 9-11 November 2008. [ Links ]

KLAKEGG, O.J., WILLIAMS, T., MAGNUSSEN, O.M. & GLASSPOOL, H. 2008. Governance frameworks for public project development and estimation. Project Management Journal, 39:S27-S42. [ Links ]

KOCH, C. & BUSER, M. 2006. Emerging metagovernance as an institutional framework for public private partnership networks in Denmark. International Journal of Project Management, 24:548-556. [ Links ]

LARCKER, D.F. & TAYAN, B. 2011. Corporate governance matters, Pearson Education, Inc., FT Press, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. [ Links ]

MARNEWICK, C. & LABUSCHAGNE, L. 2011. An investigation into the governance of information technology projects in South Africa. International Journal of Project Management, 29(6):661-670. [ Links ]

MILLER, R. & HOBBS, B. 2005. Governance regimes for large complex projects. Project Management Journal, 36(3):42-50. [ Links ]

MILLER, R., & LESSARD, D. 2000. (eds.) The strategic management oflLarge engineering projects: Shaping institutions, risks, and governance, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [ Links ]

MORRIS, P.W.G., & GERALDI, J., 2011. Managing the institutional context for projects. Project Management Journal, 42(6):20-32. [ Links ]

MÜLLER, R. 2009. Project governance. Gower Publishing Limited: Farnham, England. [ Links ]

OAKES, G., 2008. Project reviews, assurance and governance. Gower Publishing Limited: Hampshire, England. [ Links ]

PEMSEL, S. & MULLER, R. 2012. The governance of knowledge in project-based organizations. International Journal of Project Management, doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2012.02.002. [ Links ]

PRINCE2TM. 2009. Managing successful projects with PRINCE2TM. [ Links ]

PROVAN, K.G., & KENIS, P. 2008. Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(2):229-252. [ Links ]

RENZ, P.S. 2007, Project governance - Implementing corporate governance and business ethics in nonprofit organisations, Physica-Verlag Heidelberg New York. [ Links ]

RUUSKA, I., AHOLA, T., ARTTO, K. LOCATELLI, G. & MANCINI, M. 2011. A new governance approach for multi-firm projects: lessons from Olkiluoto 3 and Flamanville 3 nuclear power plant projects. International Journal of Project Management, 29(6):647-660. [ Links ]

SAMSET, K., BERG, P., & KLAKEGG, O.J. 2006. Front end governance of major public projects, EURAM 2006 Conference Oslo. [ Links ]

SANDERSON, J. 2012. Risk, uncertainty and governance in megaprojects: a critical discussion of alternative explanations. International Journal of Project Management, 30(4):432-443. [ Links ]

SHARMA, D., STONE, M. & EKINCI, Y. 2009. IT governance and project management: A qualitative study. Database Marketing & Customer Strategy Management, 16(1):29-50. [ Links ]

WILLIAMS, T., KLAKEGG, O.J., MAGNUSSEN, O.M. & GLASSPOOL, H. 2010. An investigation of governance frameworks for public projects in Norway and the UK. International Journal of Project Management, 28(1):40-50. [ Links ]

WILLIAMSON, O.E. 1981. The economics of organisation: the transaction cost approach. American Journal of Sociology, 87(3):548-577. [ Links ]

WINCH, G.M., 1989. The construction firm and the construction project: a transaction cost approach. Construction Management and Economics, 7:331-345. [ Links ]

WINCH, G.M., 2001. Governing the project process: a conceptual framework. Construction Management and Economics, 19:799-808. [ Links ]

YILIN, Y., YALING, D., LING, Y. & ZHE, W. 2008. Continuous improvement of public project management performance based on project governance. Proceedings of the 4thIEEE International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Mobile Computing: Engineering, Services and Knowledge Management (EMS), Washington, 15-17 October 2008. [ Links ]

Accepted: December 2013