Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

On-line version ISSN 2222-3436

Print version ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.17 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

ARTICLES

Projectification and its consequences: narrow and broad conceptualisations

Johann Packendorff; Monica Lindgren

School of Industrial Engineering and Management, KTH Royal Institute of Technology

ABSTRACT

In this article, we argue that an increased focus on the processes of projectification would be beneficial to project research. By introducing a distinction between narrow and broad conceptualisations of projectification, we extend this research area from its current concern with the increased primacy of projects in contemporary organisational structures into an interest for cultural and discursive processes in a society in which notions of projects are invoked. Through an illustration from our earlier empirical research on the sustenance of project work form and its consequences, the implications of applying broad conceptualisations are further discussed.

Key words: projectification, organisational structure, discourse analysis, project research.

JEL: M100, 140, 500, O320

1 Introduction

In this article we focus on the emerging notion of projectification (cf. Midler, 1995; Maylor, Brady, Cooke-Davies & Hodgson, 2006) -suggesting that it should be seen not only as a management fad and a structural trajectory in corporate re-structuring, but also as a multi-faceted phenomenon to be studied in its own right. By theorizing projectification as a cultural and discursive phenomenon as well, project research may be able to analyse both how and why corporate structures change as a result of increased project intensity, and how these change processes unfold. This includes their consequences for individuals, project teams, organisations, industrial networks and society.

The notion of projectification has emerged as projects have become a common form of work organisation in all sectors of the economy during recent decades. It is perhaps most visible in the transformation of traditional firms into "project-based firms", i.e., organisations in which almost all operations are organised as projects and where permanent structures fulfil the function of administrative support (cf. Hobday, 2000; Cicmil & Hodgson, 2006; Söderlund & Tell, 2009). The basic reason for this diffusion seems to be that the project, viewed as a task-specific and time-limited form of working, is perceived as a controllable way of avoiding all the classic problems of bureaucracy with which most "normal" organisations are struggling (Packendorff, 1995; Hodgson, 2004; Cicmil, Hodgson, Lindgren & Packendorff, 2009). The project is seen as a promise of both controllability and adventure (Sahlin-Andersson, 2002) and as a necessity when complex and extraordinary business tasks are to be managed (Cicmil et al., 2009). In that sense, project-based work is also part of the wave of new 'post- bureaucratic' organisational forms that have entered most industries during the most recent decades (cf. Clegg & Courpasson, 2004; Gill, 2002; Hodgson, 2004; Lindgren & Packendorff, 2006a; Söderlund, 2011).

It is thus not surprising to find that the scholarly debate on topics like research directions, areas of interest, theoretical and methodological assumptions relating to this development have been intense (cf. Packendorff, 1995; Söderlund, 2004; Winter, Smith, Morris & Cicmil, 2006; Cicmil et al., 2009; Jacobsson & Söderholm, 2011; Hällgren, 2012). From its very inception, project management research has been defined through its focus on the single project as unit of analysis, understood as a manageable and researchable item whose intrinsic mechanisms were to be uncovered in pursuit of project success (Packendorff, 1995). As a result of the practical developments whereby projects became a dominating form of organising in many organisations, project management research eventually also came to include inquiry into the management of bundles of projects, for instance, programmes, project portfolios, and project management offices, and the processes whereby projects and programmes were granted increased primacy as organisational forms (Maylor et al., 2006). As suggested by Söderlund (2004), a re-phrasing of the field from 'project management research' to 'project research' is thus important in order to acknowledge this development. This was also to further extend the area of interest beyond single organisations through analysing the organising of inter-firm projects (cf. Braun, Müller-Zeitz & Sydow, 2012) and through attending to patterns and developments at sectorial and societal levels (Lundin & Söderholm, 1998).

The development towards the use of projects for handling complex tasks and creative renewal in contemporary organisations has, in project research literatures, increasingly been referred to as 'projectification'1 (cf. Midler, 1995; Ekstedt, Lundin, Söderholm & Wirdenius, 1999; Bredin & Söderlund, 2006; Maylor et al., 2006; Kerr, 2008; Arvidsson, 2009; Ekstedt, 2009; Blomquist & Lundin, 2010; Aubry & Lenfle, 2012; Bergman, Gunnarson & Räisänen, 2013). In this narrow view of projectification -which Maylor et al. (2006) refer to as 'organisational projectification', research is focussed mainly on the contents and consequences of organisational re-structuring initiatives taken in order to increase the primacy of projects within a firm and its immediate supply network (p. 666). However, the concept has also been employed in a broader sense, building on recent critical inquiry into individual experiences of project work (cf. Packendorff, 2002; Lindgren & Packendorff, 2006a; Hodgson, Paton & Cicmil, 2011; Lindgren, Packendorff & Sergi, 2014) and the analysis of projects as a central discursive theme in contemporary society (cf. Lindgren, Packendorff & Wáhlin, 2001; Chiapello & Fairclough, 2002; Cicmil et al., 2009; Kuura, 2011). Taken as a whole, extant research thus presents us with a situation whereby processes of projectification are becoming increasingly relevant for the understanding of almost any aspect of the contemporary economy. At the same time, most project research appears to be empirically limited to reified and entitative notions of 'projects' or 'programmes', without reflecting on the processes whereby these phenomena are constructed, developed and institutionalised.

Arguing that an increased focus on the processes of projectification in the broad sense would be beneficial to project research, we will (1) explore the established narrow usage of the concept; (2) identify streams of thought in the emerging broad notion of projectifi-cation; and (3) provide an illustration from our own on-going research into the benefits of moving from a narrow to a broad view. Before delving into these three main issues, we will briefly relate this back to the on-going debate on current developments in project research and practice.

2 Project research - from where, to where?

Project work was for a long time seen as a marginal phenomenon in the world of organisations, and was also constructed as an opposite of dominating on-going operations (Lundin & Söderholm, 1995; Ekstedt et al., 1999; Cicmil et al., 2009). The increased use of projects and project management in almost all societal sectors has resulted in a powerful and well-established practical knowledge field that set out to provide project managers with tools and methodologies for achieving project success. It is a discipline originally focussed on forms and vocabularies for planning and control, supported by powerful conceptual and visual imagery such as Gantt charts and network diagrams. Since the 1970s, several aspects of the task of leading projects have gradually been included, such as team leadership, risk management and stakeholder management. The creation of globally-accepted project management certifications built on these forms and vocabularies and the ensuing professionalisation of the project manager's role are some of the most recent ingredients in the establishment of project management as a distinct practical discipline in business life and society (Hodgson & Cicmil, 2007). The discipline also incorporates current developments in the management of portfolios for projects and project management offices, thereby expanding into positions and organisational levels other than the single project.

Project research thus set out early to understand the specifics of this 'deviant' form of organising, materialising as projects, temporary organisations, adhocracies or an instance of post-bureaucratic organising (Clegg & Courpasson, 2004; Hodgson, 2004; Lindgren & Packendorff, 2006a). The scholarly field thus sprung out of a growing need to handle exceptional situations in a structured manner and the notion of exceptionality is still a trigger for research (cf. Hällgren & Wilson, 2011). The theoretical and practical developments have often paralleled each other, and project research has increasingly adopted theoretical concepts and constructs from general management and engineering research in order to advance understanding of projects and project management (Packendorff, 2014).

The on-going debates on theoretical influences and perspectives within project research are of vital importance for future developments, in the sense that all well-established disciplines usually find ways of escaping stagnation, at the same time becoming easy victims of precisely the same thing. Among the promises in current project research, we thus find an expanding but maturing stream of research concerned with the development of the discipline beyond established concepts and theories. It is a growing literature questioning the relevance and consequences of dominating perspectives (cf. Packendorff, 1995, Cicmil et al., 2006; Blomquist & Lundin, 2010), vividly debating, for instance, theoretical foundations (Söderlund, 2004, 2011), axiological assumptions (Cicmil & Hodgson, 2006), root metaphors (Packendorff, 1995), ontological/epistemological orientations (Winter, Smith, Morris & Cicmil, 2006; Blomquist & Lundin, 2010; Sergi, 2012), field limitations (Hallin & Karrbom Gustavsson, 2010) or the way of identifying research problems and questions (Hällgren, 2012). Twenty- years ago, project management was still a marginal phenomenon. Now it is a dominant work form in many organisations and industries, and has also attracted increased interest in general management literature (cf. Söderlund, 2011). Project researchers should thus have an even better opportunity than before to contribute to the development of general knowledge on contemporary management problems and practice (Jacobsson & Söderholm, 2011; Packendorff, 2014).

As project research gradually evolves into a distinct field in its own right, characterised by more or less notions that are taken for granted on how projects should be studied and theorised, project researchers will inevitably be met by expectations to 'perform research' in a legitimate manner. That could mean to submit to labelling projects without further ado, to exaggerate similarities between projects while suppressing the differences, and to add knowledge to extant bodies of knowledge without questioning the raison d'être of these bodies, thereby taking part in promoting and sustaining a certain view of reality, of knowledge, of good and bad. It would also imply that projects to be studied are sought within the usual industries, among the usual professionals and through the established channels (Hallin & Karrbom Gustavsson, 2010).

The alternative is, of course, to embrace the fluidity and ambiguity of the project concept, viewing project work as an ongoing social construction in society, of which we are all co-constructors, as a process of institutionalisation and change, of power and emancipation (Sergi, 2012). But that does imply that research must be founded upon explicit assumptions about ontology, epistemology and axiology, rather than slipping into the comfort of letting project management journal editors judge what is publishable. Attention to basic assumptions will not only enhance the development of project research and its relevance to general management scholars; but may also imply a changed view of how project management knowledge is made relevant and available to practitioners. Project management knowledge is often presented to the public in the form of a toolbox, generally applicable and ready for use (Packendorff, 1995), thereby conveying an image of project management practitioners in desperate need of clarity, order and standardised procedures. As noted by Pellegrinelli (2010), research should instead be a reflection and articulation...

"...of their lived experiences -what they often see and tend to do. [...] Managing is often less about planning, directing and controlling and more about coping. The absence of clarity and certainty is not an impediment to action, but a call for it - to 'get on'. Social reality for them feels malleable and changing, amenable (at least to some degree) to their influence. Some practitioners have got over, or learnt to live with, the sea-sickness" (p. 237).

Where research on projectification is concerned, the taken-for-granted nature of rational and structural approaches inherited from mainstream- project research implies obvious limitations to the research questions that can be stated, the methodologies that might be employed, the theoretical perspectives that are seen as relevant, and the analyses and conclusions that are made possible. Our notion of 'narrowness', in the views of projectification that tend to dominate project research, stems from such limitations. By limiting research on projectifi-cation to organisational restructurings only, many questions concerning the reasons, implications and consequences of projectification are left unanswered and suppressed. Our alternative, the broad notion of projectification, implies a widened approach to all these issues. The main differences between the narrow and broad views of projectification are summarised in Table 1.

The narrow and broad conceptualisations differ not only in terms of what projectification means (formal restructuring vs. cultural construction) but also in terms of consequences. While the narrow conceptualisation is aimed primarily at identifying how projectified structures are built and how this affects organisational effectiveness and prosperity, the broad conceptualisation also includes consequences for individuals, groups and societies. In the following two sections, we will further discuss the two conceptualisations, with their main underpinnings, directions and research implications.

3 Projectification as restructuring: Narrow views

The conceptualisation of projectification that we term narrow is usually based on an instrumental and structural notion of the project form as an organisational solution to certain types of tasks. This is a notion reminiscent of classic organisation theory, in which the need for handling complex and nonroutine tasks was identified during the heyday of contingency theory.

Examples of such early theoretical treatments are the identification of single unit production tasks (Woodward, 1958), the 'adhocratic' organisational form needed for innovative and extraordinary work (Mintzberg, 1979) and the notion of temporary organisational settings as rational and task-oriented exceptions from ordinary organisational life (Miller & Rice, 1967). These lines of reasoning were later extended in several ways, such as Heckscher and Donnellon's (1994) suggestion of post-bureaucratic ways of organising work according to tasks rather than departments, Goodman's (1981) treatise on temporary systems as an emerging form of work organisation, and Ciborra's (1996) idea that innovative organisations should be analysed as platforms enabling various organisational forms, improvisations and experiments in pursuit of innovation and creativity.

Against this general backdrop, the specific use of projects and project management in contemporary organisations has been further analysed in a series of writings intended to shed light on what the project form may contribute to organisational prosperity, how the project form is combined with other organisational configurations, and what managerial challenges occur in the process of projectifying on-going operations (Söderlund & Bredin, 2011). This is often done by invoking the notion of the project-based organisation as a distinct organisational form, a solution to certain strategic and managerial problems, and the end state of a series of organisational restructurings (Hobday, 2000; Söderlund & Tell, 2009). Referring to Davies et al. (2006), Maylor et al. thus trace projectification back to the insight that:

"[...] organisations in all types of industries are finding that traditional organisational structures, including functional departments, business units and divisions set up for managing high-volume throughputs of standardised products and services and for making decisions in a relatively stable technological and market environment, are no longer adequate. In the rapidly changing and increasingly turbulent and uncertain environment they face today, organisations are finding that some sort of project organisation is better suited to the kind of one-off or temporary problems that they have to deal with" (Maylor et al., 2006:664).

In contemporary literatures, this increased use of the project-based form in an organisation takes several different shapes and is justified with reference to both historical developments and intended benefits. While the individual project as such, a temporary, unique, goal-focussed and complex undertaking (cf. Packendorff, 1995), seems to be a rather standardised matter, there is a range of possible ways of incorporating it into an existing organisation. The various matrix arrangements available are a recurring theme in the literature (Larson & Gobeli, 1987; Davies et al., 2006; Maylor et al., 2006; Arvidsson, 2009), as well as the various solutions to the problem of integrating multi-project-based operations into coordinated portfolios through standardised project management methods and project management offices (De Maio, Verganti & Corso, 1994; Engwall & Jerbrant, 2003; Blomquist & Müller, 2006; Aubry et al., 2007). The project-based organisational form thus centres on the individual project as the unit in which production and innovation take place, in a setting characterised by product/systems complexity, cross-functional cooperation, batch-oriented production, horizontal communication and team-based work (Söderlund & Tell, 2009; Söderlund & Bredin, 2011).

A limited number of studies have focussed explicitly on the processes of projectification over time. Midler (1995) and Söderlund & Tell (2009) describe projectification as a series of restructurings whereby traditional functional structures are gradually transformed into heavyweight project forms and projects become increasingly autonomous and customer-focussed. In both these cases, the drivers are external market demands, implying increased customisation and technology integration, in combination with internal aspirations to simplify organisational communication and decision-making and to empower project teams. In their review of several studies of projectification, Maylor et al. (2006) also add that these restructurings imply an increased number of projects, increased reliance on codified bodies of project management knowledge (such as stage-gate models and inhouse standardised frameworks), an increased emphasis on project performance when evaluating organisational effectiveness, and an increased prevalence of project management offices and similar functional devices geared to project-based operations.

Some of this research is also concerned with the consequences of projectification. Maylor et al. (2006), Turner, Huemann & Keegan, (2008) and Söderlund & Bredin (2011) point to potentially negative consequences for both organisational and individual levels, such as the danger of re-bureaucratisation, neglecting the need for integration of projects into programmes or portfolios, limited time for knowledge development, overwhelming deadline stress, and lack of trust and social continuity. Jerbrant (2014) emphasises that projectification is indeed driven by perceived consequences, in the sense that every subsequent restructuring solves some problems but also creates new ones, thus portraying projectification also as a series of emerging uncertainties that have to be handled.

All in all, the narrow conceptualisation of projectification shows great efforts to identify the basic structural tenets of project-based organisational forms and the conditions associated with the gradual restructuring of former functional organisations. The literature also demonstrates a well-developed understanding of the relation between market developments, technological change and the aspects of organisations that are affected and altered in the processes of projectification. Some research has also taken individual perspectives into account, departing from not only organisational effectiveness but also individual well-being as central to the understanding of consequences and outcomes. The basic weakness of the narrow view, i.e., that projectification is analysed as a rational and straightforward process rather than as a development characterised by aspects such as bounded rationality, power and politics, cultural norms and constructs is, however, not alleviated.

4 Projectification as cultural and discursive processes: Broad conceptualisations

The broad conceptualisation of projectification involves the cultural and discursive societal processes whereby projects and project-like- circumstances are institutionalised in individual lives, the organising of all sorts of work, and society at large. Unlike the definition by Maylor et al. (2006) of 'societal projectifi-cation', this broad view is not a mere extension of the study of the implementation of project-based structures beyond firms and their immediate supply chain networks, but rather a different theoretical view in which formal structural units are seen as institutionalised social constructions and not as stable entities. It is a conceptualisation that draws not only on sociological understandings of an increasingly episodic orientation in contemporary society (cf. Bennis & Slater, 1968; Sennett, 1998), project-oriented discursive modes of justification (Chiapello & Fairclough, 2002), but also on the tendency to perceive all sorts of individual and societal processes as temporary and transitory by nature:

"Many observers have noted the contemporary decay in production of thoroughgoing literary Utopias (in sharp contrast with the ferment of the 18th and 19th centuries), and their replacement by satirical or polemical versions of life in the mass society of the future (e.g., George Orwell's 1984); what has gone unremarked is the enormous proliferation of short-term quasi-Utopias of all sorts -conferences, meetings, "task forces", research projects, experiments and training exercises. It is as if we have traded the grand visions of social life as it might be lived for miniature societies, to which one can become committed intensively, meaningfully, satisfyingly - and impermanently" (Miles, 1964:465).

In their discussion on the cultural and political modes of understanding and justifying reality with reference to the history of mankind, Chiapello & Fairclough (2002) claim that a new 'justificatory regime' is emerging in contemporary society - the project-oriented cité. In comparison with the six historical cités - which were based on, e.g., religious beliefs, bourgeois civil society values, industrial logics or market mechanisms - the project-oriented justificatory regime puts primacy on activity, project initiation and social networks as basic tenets of societal activity. The successful and prosperous individual is an adaptive, flexible and connective team player, able to generate enthusiasm and handle multiple cultural traditions, always prioritising availability, employability and new projects over social stability and lifelong plans (cf. also Bennis & Slater, 1968; Lindgren et al., 2001).

"In contrast with the Industrial Cité in which activity means 'work' and being active means 'holding a steady and wage-earning position', in the Project-oriented Cité activity overcomes the oppositions between work and non-work, steady and casual, paid and unpaid, profitsharing and volunteer work. Life is conceived as a series of projects, the more they differ from one another, the more valuable they are. What is relevant is to be always pursuing some sort of activity, never to be without a project, without ideas, to be always looking forward to, and preparing for, something along with other persons, who are brought together by the drive for activity. When starting on a new project, all participants know that it will be short-lived. The perspective of an unavoidable and desirable end is built in the nature of the involvement, without curtailing the enthusiasm of the participants. Projects are well adapted to networking for the very reason that they are transitory forms: the succession of projects, by multiplying connections and increasing the number of ties, results in an expansion of networks" (Chiapello & Fairclough, 2002:192).

Beyond the notion of projects as a core aspect of contemporary societal life, projectification is also discursively linked to the strong and dominating notion of project management as a standardised field of codified knowledge (cf. Hodgson & Cicmil, 2007). By naming something as a 'project', a number of discursive expectations on the work process are brought from the well-established project management discipline into the local situation by project participants (Pellegrinelli, 2010; Lindgren et al., 2014). Projects are usually expected to be planned, controlled, detached episodes of passion, dedication and commitment, arenas for flexible action and task-focussed social relations (Nocker, 2009), as strictly coordinated and enclosed activity systems (Bechky, 2006). They are also constructed as exceptional work episodes, as temporary 'states of emergency' where danger and urgency prevail and everyday norms and rules do not apply (Lindgren & Packendorff, 2006a; Lindahl, 2007). Hence, as extraordinary settings in- which individuals submit to almost any kind of conditions because it is a only passing moment. The labelling of projects is also closely related to reification (Cicmil et al., 2006). 'A project' is often compartmentalised by its co-constructors into an independent and distinct object that is controllable and manageable if proper methodologies are used. The inherent performativity of the project concept (Pellegrinelli, 2010; Sage, Dainty & Brookes, 2013), with its emphasis on rationality and controlled passion can thus be expected to be an important aspect of understanding projectification.

The processes and consequences of projectification have been increasingly studied in this fashion during the past decade (cf. Lindgren et al., 2001; Sahlin-Andersson, 2002; Grabher, 2002; Clegg & Courpasson, 2004; Hodgson, 2004; Lindgren & Packendorff, 2006a, 2006b, 2007; Cicmil et al., 2009). This research has emphasised the need for examining the underlying discursive developments in which the notion of rational project management has become a legitimate and desirable phenomenon in contemporary society and a driver behind the creation of projectified organisations within which the work occurs. Among the themes of these studies we find, e.g., the (re-)masculinisation of post-bureaucratic work practices (Gill, 2002; Buckle & Thomas, 2003; Lindgren & Packendorff, 2006a; Styhre, 2011), the performative notion of project management as creeping into established professional identities (Hodgson, 2002; Lindgren & Packendorff, 2007; Paton, Hodgson & Cicmil, 2010), and the construction of new power relations in the wake of standardisation and professional certification initiatives (Hodgson & Cicmil, 2007). The project management discourse thus contributes to the reification of projects as distinct, given, unquestionable and manageable items separated from their history and context (Cicmil & Hodgson, 2006; Lindgren et al., 2014); to the dichotomisation of projects vis-á-vis permanent and stable organisational arrangements, (Cicmil et al., 2009); to the 'grandiosification' of projects as a superior alternative to ineffective, rigid, boring bureaucracies (Gill, 2002; Grabher, 2002), and to the compartmentalisation of projects into settings in which admirable achievements take place under conditions where normal rules do not apply (Lindgren & Packendorff, 2006a; Lindahl, 2007). Some recent research also highlights the emotional consequences of the projectified work, portraying projects as emotionally charged and potentially addictive and harmful spaces (Rehn & Lindahl, 2011; Rowlands & Handy, 2012; Lindgren et al., 2014).

Amid the consequences of projectification, it is also important to note the ambitions and hopes tied to projects and how such ambitions and hopes have become taken for granted in project work. Through goal-setting and planning, ambitions and hopes are projected into the future, almost to the extent that the future is 'lived' in advance, taken for granted and secured through project planning (Pitsis, Clegg, Marosszeky & Rura-Polley, 2003). Being successful in a projectified society is closely linked to being available, flexible and connected, while sacrificing lifelong plans, stable conditions and social predictability (Chiapello & Fairclough, 2002). Invoking the project discourse thus implies not only the exclusion and suppression of non-project aspects, but also the disconnecting of everything that does not fit into the project management discourse.

To sum this up, the broad conceptualisation of projectification includes the focus on organisational restructuring in the narrow view, but extends the notion of projectification into societal and individual life and employs cultural, sociological and critical theoretical perspectives in the analysis of processes and the consequences of this. It implies that the increased prevalence of projects and project management processes in organisations is not only analysed from the perspective of rational structural responses to competitive and technological changes, but is also set in a cultural and discursive context in which notions of projects and project management are central to societal development in general. We will now illustrate how these insights can be useful in the study of projectification in practice.

5 Applying narrow and broad views of projectification: An empirical illustration

In this section we will return to some of our earlier research on projectification processes in- order to illustrate how a broad conceptualisation may contribute to knowledge and theoretical development. In the particular study revisited here, we considered the consequences of increased project-orientation in organisations (cf. Lindgren & Packendorff, 2006a; 2006b; 2007, 2008, 2009; Lindgren et al., 2014). A range of organisations in ICT consulting and the performing arts were studied by means of interviews with individuals who were working in projects and who were members of the same project teams. This means that individuals were asked for the spontaneous story of their life, including both work and life in general, during the implementation time of their respective projects. Individual interviews lasted for about two-three hours. After typing up the tape-recorded material, we extracted different narratives linked to aspects of projectification by means of thematic analysis. Inspired by Martin's (2001) method, we thus emphasised narratives on the production and re-production of the project work form, the invocation of project management discourses, how the individuals related their way of living to what was happening in 'projects', and the dynamic relations between organisation and 'projects'.

It appeared that all the organisations studied experienced similar problems in the wake of their on-going projectification, usually manifesting in individual stress, delays and budget overruns in projects, and a lack of overview of the project portfolio.

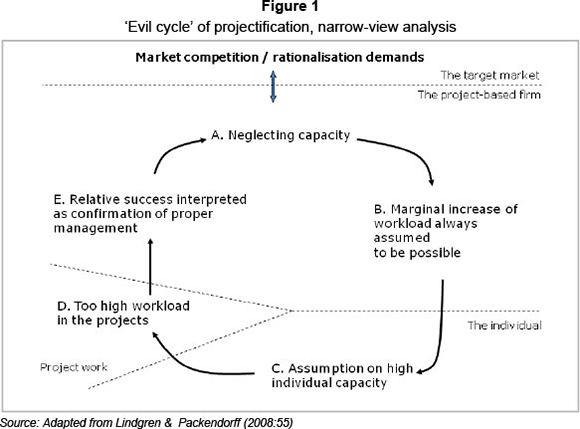

Integrating the various problems into a model of ongoing projectification (Lindgren & Packendorff, 2008), we found that they were indeed related and tended to sustain each other over time. We summarised this in terms of an 'evil cycle of projectification' (see Figure 1) built from a narrow conceptualisation.

According to the narrow-view analysis, the legacy of neglecting capacity issues in project-based environments (stage A) is reflected in the attitude that additional projects can always be added and that starting a project earlier will imply that it will also be delivered earlier (B). When adding projects to the portfolio, it is usually possible to identify individuals who have enough spare time to take on additional tasks (C). The usual consequences of this are delays and budget overruns in project implementation (D), as it now appears that the organisational capacity was indeed lacking in terms of overload and managerial attention. Owing to improvisational measures and fire-fighting, most projects are still being delivered satisfactorily (E). The impediments to learning and improvement thus remain too significant for the basic lack of understanding concerning organisational capacity to be alleviated (A).

The measures taken in the organisations studied included support and anti-stress training for employees, increased emphasis on leadership and control in the individual projects, and the introduction of project portfolio management models. Nevertheless, the basic problems tended to persist.

This narrow view analysis of the processes of projectification reveals not only the incremental and stepwise manner in which the project form is granted primacy in organisations (cf. Jerbrant, 2014), but also the fact that the project-based organisations may well become subject to inertia and bureaucratisation (cf. also Hodgson, 2004). Processes of projectification imply not only that operations are split up into flexible and innovative units, but also that several aspects of repetitive organising that could also be beneficial in project-based settings are left behind. In this case, we find not only the familiar tendency to overlook issues related to capacity and load in project work (cf. Wheelwright & Clark, 1992), but also an absence of HRM in project situations (Bredin & Söderlund, 2006), neglect of the additional pressures on employees caused by- organisational complexity, and multiple deadlines (cf. Turner et al., 2008; Cicmil & Gaggiotti, 2009), and a lack of insight into the operational risks related to reliance on heroic action. In the cases studied here, the notion of projects serves not only to structure operations in a dynamic and flexible way, but also to transfer responsibility and accountability from managers to teams and individuals without offering relevant organisational infrastructures or resources. From this narrow analysis of projectification, we can thus identify several important aspects of problematic organisational restructurings and point to possible ways of resolving them. At the same time, it was clear to us that many of these problems were already familiar to managers and employees in the organisations studied, and that almost nobody could imagine an alternative way of organising project-based work. As noted by the ICT consultant Carl and his project leader Eric:

"The salespersons will always promise the customers quicker and cheaper projects than possible. They will always make them believe that we will fix their problems through a fast installation of our software, but in practice, we always have to make far-reaching modifications. And those modifications mean delays. When the project schedule cracks down, we just have to sit there with our extra hours. It has been like that in almost all my projects" (Carl).

"Well, you don't actually plan for that kind of work peaks. When you make a time schedule, you estimate the duration of each work package and then add some slack. You don't plan for any bigger problems. No projects go exactly as planned and you don't know everything from start. But if you were to investigate and estimate everything beforehand, you would never come to the implementation phase" (Eric).

In order to understand how the various actors tend to be repeatedly caught up in such situations, a broad notion of projectification can be employed, whereby the actions taken are seen as internalising cultural values and invoking performative discourses on projects and project management. From such a perspective (Figure 2), general discursive notions of projects as temporary, extraordinary, adventurous, controllable and delimited are drawn upon in work episodes labelled 'projects'. Extraordinarisation implies a discursive view of all projects as more or less unique, so it is not really possible to handle them together in a fully-integrated way. This is supported by the notion of projects as temporary, so they spill over to a view of project work as temporary, optimistically framed as opportunities that cannot be missed. People justify the fact that they are at the mercy of such conditions by drawing upon project-orientation in constructing their identities, performing as flexible, innovative, dedicated professionals. When problems appear, they may question the number of concurrent projects, thereby dismissing the situation as a matter of planning. They thus understand the situation to require even more project planning rather than questioning the processes of extraordinarisation and temporarisation. The consequent difficulties are then- compartmentalised as isolated mistakes and as instances of heroic action that have created some sense of meaningfulness and excitement. When actors frame their work in such a way and take this way of working for granted as inevitable, project work and its consequences will be justified as normal and necessary and will thus be sustained over time.

At the same time, other notions appeared to be suppressed and sometimes non-existent, such as repetitiveness (people and organisations live through a series of projects, not one project only), normalisation (project work is and should be seen as everyday things in these contexts), resilience (awareness of the limits of heroic masculinity is needed), risk (project risks and deviations cannot be fully controlled) and inter-relatedness (projects are related to each other and to the rest of the organisation throughout their existence). It can thus be concluded that the problems identified and their sustainability may depend upon invoking project management in a traditional and non-reflective way, and that some of the measures taken may actually aggravate the situation, as they are also based on traditional notions.

With this brief illustration, we maintain that a broad conceptualisation of projectification offers a better understanding of its reasons, as well as new ways of explaining the persistence and continuation of project-based work forms despite their problematic consequences. Pro-jectification is driven not only by notions of suitability and effectiveness for certain organisational tasks, but also by the widespread legitimacy of project management as a rational managerial toolbox and project-orientation, as an internalised understanding of what it means to be a successful, productive and enterprising individual in contemporary society. At the same time, it should be noted that this broad understanding is not external to narrow conceptualisations and understanding of projectification, but rather builds on and includes them, but with different ontological, epistemological and axiological assumptions as points of departure. It also implies that new ways of formulating and resolving consequences of projectification can be identified (Spicer, Alvesson, & Kärreman, 2009). For example, the broad conceptualisation offers new ways of attending to the unwanted and problematic consequences of organisational projectification as identified through research employing narrow conceptualisations; by redefining problems with overload, stress or high project failure rates as problems related to institutionalised over-optimism, responsibilisation of individuals and expectations of omnipotence in project control, focus could shift to organisational cultures and management ideologies as sources of improvement instead of project maturity models and control systems.

6 Conclusion

In this article, we have argued that an increased focus on the processes of projectification would be beneficial to project research. By introducing the distinction between narrow and broad conceptualisations of projectification, we have extended this research area from its current concern with the increased primacy of projects in contemporary organisational structures (cf. Maylor et al, 2006) to an interest in the cultural and discursive processes in society in which notions of projects are invoked. What separates the two conceptualisations is not the levels or units of analysis, but basic research assumptions.

Based on this, we propose that future research on projectification should actively employ a view of projects and project-based organising as cultural and discursive phenomena.

We would thus not only be able to add to our knowledge of how project-based work is organised in everyday practice, but also increase our understanding of how societal discourse, organisational culture and individual identity construction are inter-related in the reproduction of project work in specific and post-bureaucratic organisation in general. We would also become more aware of both the full consequences of project-based work practices, and possible ways of attending to these consequences critically and constructively.

The study of projectification is not a matter for project researchers alone. Scholars of organisational theory interested in 'bringing work back in' to enhance understanding of contemporary organisational matters (cf. Barley & Kunda, 2001) should find studies of projectification most useful in developing new theoretical notions on, for instance, post-bureaucratic organisations, virtual organisations, entrepreneurial processes, the organisation of innovation work, new leadership forms and new HRM practices. When work processes, complex tasks, long-term work change and life itself are increasingly treated as instances of project management, what happens, who benefits and what power structures emerge? Are we experiencing a shift towards post-bureaucratic organisation, or is it better understood as re-bureaucratisation at different levels of analysis?

What about projects as outbursts of emotional labour, as projections of desire and hope rather than rationally planned activity systems? In addition to this, work-life problems in projectified work need continued attention, as do also the related issues of leadership and followership, of entrepreneurship and innovation. Project research has an important role to play in such a development.

References

ARVIDSSON, N. 2009. Exploring tensions in projectified matrix organisations. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 25(1):97-107. [ Links ]

AUBRY, M. & LENFLE, S. 2012. Projectification: Midler's footprint in the project management field. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 5(4):680-694. [ Links ]

AUBRY, M., HOBBS, B. & THUILLIER, D. 2007. A new framework for understanding organisational project management through the PMO. International Journal of Project Management, 25:328-336. [ Links ]

BARLEY, S.R. & KUNDA, G. 2001. Bringing work back in. Organization Science, 12(1):76-95. [ Links ]

BECHKY, B. 2006. Gaffers, gofers and grips: Role-based coordination in temporary organizations. Organization Science, 17(1):3-21. [ Links ]

BENNIS, W.G. & SLATER, P. 1968. The temporary society. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

BERGMAN, I., GUNNARSON, S. & RÄISÄNEN, C. 2013. Decoupling and standardization in the projectification of a company. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 6(1): 106-128. [ Links ]

BLOMQUIST, T. & LUNDIN, R.A. 2010. Projects - real, virtual or what? International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 3(1):10-21. [ Links ]

BLOMQUIST, T. & MÜLLER, R. 2006. Practices, roles, and responsibilities of middle managers in program and portfolio management. Project Management Journal, 37(1):52-66. [ Links ]

BRAUN, T., MÜLLER-SEITZ, G. & SYDOW, J. 2012. Project citizenship behaviour? - An explorative analysis at the project-network-nexus. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 28(4):271-284. [ Links ]

BREDIN, K. & SÖDERLUND, J. 2006. Perspectives on human resource management: An explorative study of the consequences of projectification in four firms. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, 6(1):92-113. [ Links ]

BUCKLE, P. & THOMAS, J. 2003. Deconstructing project management: a gender analysis of project management guidelines. International Journal of Project Management, 21:433-441. [ Links ]

CHIAPELLO, E. & FAIRCLOUGH, N. 2002. Understanding the new management ideology: A transdisciplinary contribution from critical discourse analysis and new sociology of capitalism. Discourse & Society, 13(2):185-208. [ Links ]

CIBORRA, C.U. 1996. The platform organization: Recombining strategies, structures and surprises. Organization Science, 7(2):103-118. [ Links ]

CICMIL, S. & GAGGIOTTI, H. 2009. Who cares about project deadlines? A processual-relational perspective on problems with information sharing in project environments. International Journal of Knowledge Management Studies, 3(3/4):222-240. [ Links ]

CICMIL, S. & HODGSON, D. 2006. New possibilities for project management theory: A critical engagement. Project Management Journal, 37(3):111-122. [ Links ]

CICMIL, S., WILLIAMS, J. THOMAS & HODGSON, D. 2006. Rethinking project management: researching the actuality of projects. International Journal of Project Management, 24:657-686. [ Links ]

CICMIL, S., HODGSON, D., LINDGREN, M. & PACKENDORFF, J. 2009. Project management behind the facade. ephemera: theory & politics in organization, 9(2):78-92. [ Links ]

CLEGG, S. & COURPASSON, D. 2004. Political hybrids: Tocquevillean views on project organisations. Journal of Management Studies, 41(4):525-547. [ Links ]

DAVIES, A., BRADY, T. & HOBDAY, M. 2006. Charting a path toward integrated solutions. MIT Sloan Management Review, 47(3):39-48. [ Links ]

DE MAIO, A., VERGANTI, R. & CORSO, M. 1994. A multi-project management framework for new product development. European Journal of Operational Research, 78(2):178-191. [ Links ]

EKSTEDT, E. 2009. A new division of labour: The "projectification" of working and industrial life. In M-A. Moreau (ed.) Building Anticipation of Restructuring in Europe, 31-53. Brussels: PIE Peter Lang. [ Links ]

EKSTEDT, E., LUNDIN, R.A., SÖDERHOLM, A. & WIRDENIUS, H. 1999. Neo-industrial organizing: action, knowledge formation and renewal in a project-intensive economy. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

ENGWALL, M. & JERBRANT, A. 2003. The resource allocation syndrome: The prime challenge of multi-project management? International Journal of Project Management, 21(6):403-409. [ Links ]

GILL, R. 2002. Cool, creative and egalitarian? Exploring gender in project-based new media work in Europe. Information, Communication & Society, 5(1):70-89. [ Links ]

GOODMAN, R.A. 1981. Temporary systems: professional development, manpower utilization, task effectiveness, and innovation. New York: Praeger. [ Links ]

GRABHER, G. 2002. Cool projects, boring institutions: Temporary collaboration in social context. Regional Studies, 36(3):205-214. [ Links ]

HALLIN, A. & KARRBOM GUSTAVSSON, T. 2010. Digging wider and deeper - revealing the hegemony and symbolic power of 'project' studies and practice. International Journal of Project Organisation and Management, 2(1):1-15. [ Links ]

HÄLLGREN, M. 2012. The construction of research questions in project management. International Journal of Project Management, 30(7):804-16. [ Links ]

HÄLLGREN, M. & WILSON, T.L. 2011. Opportunities for learning from crises in projects. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 4(2):196-217. [ Links ]

HECKSCHER, C. & DONNELLON, A. (eds.) 1994. The post-bureaucratic organization: new perspectives on organizational change. London: Sage. [ Links ]

HOBDAY, M. 2000. The project-based organisation: An ideal form for managing complex products and systems? Research Policy, 29:871-893. [ Links ]

HODGSON, D. 2002. Disciplining the professional: The case of project management. Journal of Management Studies, 39(6):803-821. [ Links ]

HODGSON, D. 2004. Project work: the legacy of bureaucratic control in the post-bureaucratic organization. Organization, 11(1):81-100. [ Links ]

HODGSON, D. & CICMIL, S. 2007. The politics of standards in modern management: Making 'the project' a reality. Journal of Management Studies, 44:431-450. [ Links ]

HODGSON, D., PATON, S. & CICMIL, S. 2011. Great expectations and hard times: The paradoxical experience of the engineer as project manager. International Journal of Project Management, 29(4):374-382. [ Links ]

JACOBSSON, M. & SÖDERHOLM, A. 2011. Breaking out of the straitjacket of project research: In search for contribution. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 4(3):378-388. [ Links ]

JERBRANT, A. 2014. A maturation model for project-based organisations: And uncertainty management as an always remaining multi-project management focus. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 17(1). [ Links ]

KERR, R. 2008. Transferring new public management to the periphery: UK international development organizations applying project technology to China. International Studies of Management and Organization, 38(4):58-77. [ Links ]

KUURA, A. 2011. Policies for projectification: Support, avoid or let it be? Discussions on Estonian Economic Policy: Theory and Practice of Economic Policy, 19(1):92-111. [ Links ]

LARSON, E. W. & GOBELI, D.H. 1987. Matrix management: Contradictions and insights. California Management Review, 29(4):126-138. [ Links ]

LINDAHL, M. 2007. Engineering improvisation: the case of Wärtsilä. In Guillet de Monthoux, P., Gustafsson, C. & Sjöstrand, S-E. (eds.) Aesthetic leadership: managing fields of flow in art and business, 155-168. London: Palgrave. [ Links ]

LINDGREN, M. & PACKENDORFF, J. 2006a. What's new in new forms of organizing? - On the construction of gender in project-based work. Journal of Management Studies, 43(4):841-866. [ Links ]

LINDGREN, M. & PACKENDORFF, J. 2006b. Projects and prisons. In D. Hodgson and S. Cicmil (eds.) Making projects critical. London: Palgrave. [ Links ]

LINDGREN, M. & PACKENDORFF, J. 2007. Performing arts and the art of performing - On co-construction of project work and professional identities in theatres. International Journal of Project Management, 25:354-364. [ Links ]

LINDGREN, M. & PACKENDORFF, J. 2008. Frán projektarbete till projektintensivt arbete: Människan och projektarbetets institutionalisering. In T. Stjernberg, J. Söderlund & E. Wikström (eds.) Projektliv: Villkorför uthälligprojektverksamhet. Lund: Studentlitteratur. [ Links ]

LINDGREN, M. & PACKENDORFF, J. 2009. Project leadership revisited: Towards distributed leadership perspectives in project research. International Journal of Project Organisation and Management, 1(3):285-308. [ Links ]

LINDGREN, M., PACKENDORFF, J. & SERGI, V. 2014. Thrilled by the discourse, suffering through the experience: Emotions in project-based work. Human Relations (forthcoming). [ Links ]

LINDGREN, M., PACKENDORFF, J. & WÄHLEN, N. 2001. Resa genom arbetslivet: Om människors organisationsbyten och identitetsskapande. Lund: Academia Adacta. [ Links ]

LUNDIN, R.A. & SÖDERHOLM, A. 1995. A theory of the temporary organization. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 11(4):437-455. [ Links ]

LUNDIN, R.A. & SÖDERHOLM, A. 1998. Conceptualizing a projectified society: Discussion of an eco-institutional approach to a theory on temporary organizations. In R.A. Lundin and C. Midler (eds.) Projects as arenas for renewal and learning processes, 13-23. Norwell: Kluwer. [ Links ]

MARTIN, P.Y. 2001. "Mobilizing masculinities": women's experiences of men at work. Organization, 8(4):587-618. [ Links ]

MAYLOR, H., BRADY, T., COOKE-DAVIES, T. & HODGSON, D. 2006. From projectification to programmification. International Journal of Project Management, 24(8):663-674. [ Links ]

MIDLER, C. 1995. "Projectification" of the firm: The Renault case. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 11(4):363-375. [ Links ]

MILES, M.B. 1964. On temporary systems. In Miles, M.B. (ed.) Innovation in education. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

MILLER, E. J. & RICE, A. K. 1967. Systems of organizations: the control of task and sentient boundaries. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

MINTZBERG, H. 1979. The structuring of organizations: A synthesis of the research. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

NOCKER, M. 2009. Struggling to 'fit in': On belonging and the ethics of sharing in project teams. Ephemera: theory & politics in organization, 9(2):149-167. [ Links ]

PACKENDORFF, J. 1995. Inquiring into the temporary organization: new directions for project management research. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 11(4):319-333. [ Links ]

PACKENDORFF, J. 2002. The temporary society and its enemies: Projects from an individual perspective. In K. Sahlin-Andersson & A. Söderholm (eds.) Beyond Project Management: New Perspectives on the Temporary-Permanent Dilemma. Copenhagen: CBS Press. [ Links ]

PACKENDORFF, J. 2014. Should project management get carried away? On the unfinished business of critical project studies. In R.A. Lundin & M. Hällgren (eds.) Advancing research on projects and temporary organizations. Copenhagen: CBS Press. [ Links ]

PATON, S., HODGSON, D. & CICMIL, S. 2010. Who am I and what am I doing here? Becoming and being a project manager. Journal of Management Development, 29(2):157-166. [ Links ]

PELLEGRINELLI, S. 2010. What's in a name? Project or programme? International Journal of Project Management, 29:232-40. [ Links ]

PETERS, T. 1992. Liberation management: Necessary disorganization for the nanosecond nineties. London: Macmillan. [ Links ]

PITSIS, T.S., CLEGG, S.R., MAROSSZEKY, M. & RURA-POLLEY, T. 2003. Constructing the Olympic dream: A future perfect strategy of project management. Organization Science, 14(5):574-590. [ Links ]

REHN, A. & LINDAHL, M. 2011. Leadership and the 'right to respect' - on honour and shame in emotionally charged management settings. European Journal of International Management, 5(1):62-79. [ Links ]

ROWLANDS, L. & HANDY, J. 2012. An addictive environment: New Zealand film production workers' subjective experiences of project-based labour. Human Relations, 65(5):657-680. [ Links ]

SAGE, D., DAINTY, A. & BROOKES, N. 2013. Thinking the ontological politics of managerial and critical performativities: An examination of project failure. Scandinavian Journal of Management (forthcoming). [ Links ]

SAHLIN-ANDERSSON, K. 2002. Project management as boundary work: Dilemmas of defining and delimiting. In K. Sahlin-Andersson and A. Söderholm (eds.) Beyond Project Management: New Perspectives on the Temporary-Permanent Dilemma. Copenhagen: CBS Press. [ Links ]

SENNETT, R. 1998. The Corrosion of Character: The Personal Consequences of Work in the New Capitalism. New York: WW Norton & Co. [ Links ]

SERGI, V. 2012. Bounded becoming: Insights from understanding projects in situation. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 5(3):345-363. [ Links ]

SPICER, A., ALVESSON, M. & KÄRREMAN, D. 2009. Critical performativity: The unfinished business of critical management studies. Human Relations, 62(4):537-560. [ Links ]

SÖDERLUND, J. 2004. Building theories of project management: Past research, questions for the future. International Journal of Project Management, 22(3):183-191. [ Links ]

SÖDERLUND, J. 2011. Pluralism in project management: Navigating the crossroads of specialization and fragmentation. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(2):153-176. [ Links ]

SÖDERLUND, J. & BREDIN, K. 2011. Human resource management in project-based organisations: The HR quadriadframework. London: Palgrave Macmillan [ Links ]

SÖDERLUND, J. & TELL, F. 2009. The P-form organization and the dynamics of project competence: Project epochs in Asea/ABB, 1950-2000. International Journal of Project Management, 27:101-112. [ Links ]

STYHRE, A. 2011. The overworked site manager: Gendered ideologies in the construction industry. Construction Management and Economics, 29:943-955. [ Links ]

TURNER, R., HUEMANN, M. & KEEGAN, A. 2008. Human resource management in the project-oriented organization: Employee well-being and ethical treatment. International Journal of Project Management, 26: 577-585. [ Links ]

WHEELWRIGHT, S.C. & CLARK, K.B. 1992. Creating project plans to focus product development. Harvard Business Review, 70(2):70-82. [ Links ]

WINTER, M., SMITH, C., MORRIS, P. & CICMIL, S. 2006. Directions for future research in project management: The main findings of a UK government-funded research network. International Journal of Project Management, 24:638-649. [ Links ]

WOODWARD, J. 1958. Management and technology. London: Her Majesty's Stationary Office. [ Links ]

Accepted: December 2013

Endnote

1 As noted by Söderlund & Bredin (2011:9), there are also similar conceptualisations for this phenomenon, such as 'projectization' (Peters, 1992), projectivization' (Ekstedt et al., 1999) and 'project intensification' (Bredin & Söderlund, 2006). In this article, the concept of 'projectification' is seen as also including these other labels for the phenomenon.