Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

On-line version ISSN 2222-3436

Print version ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.17 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

ARTICLES

Linking project-based production and project management temporary systems in multiple contexts: an introduction to the special edition

Leon OerlemansI; Tinus PretoriusII

ITilburg University, the Netherlands Graduate School of Technology Management, University of Pretoria

IIGraduate School of Technology Management, University of Pretoria

1 Introduction

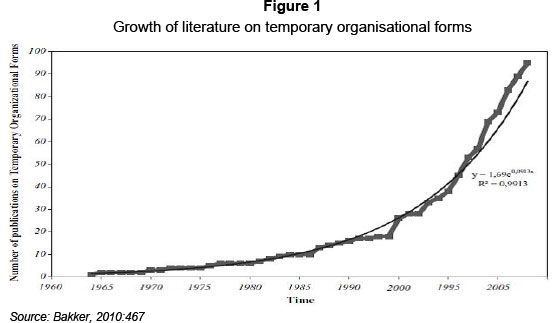

As organisations in more and more industries look for flexible ways of production in the wake of rapidly changing market environments, project-based organising is becoming an increasingly important mode of organisation (Eisenhardt & Tabrizi, 1995). Whereas project-based organisation was traditionally mainly the domain of industries such as film making (Sorenson & Waguespack, 2006), theatre (Goodman & Goodman, 1976), and construction (Gann & Salter, 2000), a project-based mode of operation has recently pervaded many other sectors in the economy, including software development, advertising, biotechnology, consulting, emergency response, fashion, television and complex products and systems (Grabher, 2004; Hobday, 2000). This increasing prevalence- is reflected in an exponentially growing body of research (Bakker, 2010), which has made marked progress in areas such as project-based learning (Prencipe & Tell, 2001), project-based innovation (Eisenhardt & Tabrizi, 1995) and project-based careers (Jones, 1996). As a consequence, research on project organisation has moved from being a narrow specialty domain toward being a broad research paradigm, attending to a broad audience in organisation science and beyond (Sydow et al., 2004).

In a fairly recent review paper, Bakker (2010) shows that in the period 1988-2008 scholarly attention, as indicated by publications in books and ISI-indexed journals, grew exponentially (see Figure 1). Comparing the number of publications in the period 1988-1998 with the period 1998-2008, he observed an increase of almost 340%.

Within this shift of attention to project-based organisation, which initially had a predominant intra-organisational focus, there has recently been a noted second trend: the trend that project work today increasingly requires the flexible and temporary involvement of external partners (Maurer, 2010). By pooling the expertise and resources of multiple organisations for the execution of project tasks, such inter-organisational project ventures have been proposed to be excellent vehicles to, amongst others, achieve economies of scale, come up with innovative products, learn, and hedge risks (Kenis, Janowicz-Panjaitan & Cambré, 2009).

Project-based work in and across organisations poses new challenges for many organisational processes (creativity, learning, innovation, decision-making) and their outcomes and management (e.g. project governance). Against this backdrop, the South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences wished to publish a Special Edition devoted to topics- linking project-based organising and project management.

2 Some definitions

This special edition focuses on project-based organisations and projects. These ways of organising production of products and services can be captured in the overarching concept of temporary systems. A temporary system or organisation in business and science is typically defined as a collaborative endeavor that is consciously planned to arrive at a particular goal. They can be further characterised as temporary rather than permanent organisational systems that are constituted of project teams (individuals/organisations) within or across organisations to accomplish particular tasks under time constraints. Table 1 presents further details of differences between temporary and permanent organisations.

Temporary organisational systems come in different shapes. Examples are disaster and rescue teams, groups of diverse professionals designing and performing in theatre productions, or quickly formed temporary systems to fight terrorist attacks. In this special edition, the focus will be on so-called structurally prepared ones (see Raab et al., 2009:174) such as project-based organisations and projects.

The project-based organisation is an organisational form in which the project, or multiple projects, is the primary organisational unit for production, innovation, change, and- competition (Hobday, 2000:874). Project-based organisations are commonly used in the forprofit manufacturing context; the form is also implemented in other organisations, both public and private, including law and consultancy firms, marketing, the film industry, and advertising. While a project can be defined as any activity with a defined set of resources, goals, and time limit, e.g., for information technology or new materials., within a PBO the project is the primary business mechanism for coordinating and integrating all the main business functions of the firm e.g., operations, R&D, engineering, innovation, marketing, human resources, and finance.

3 Project embeddedness and project management

For a long time, academic research treated projects as 'islands' (Engwall, 2003). The main research focus was on the structures and dynamics of individual projects, typically discussed from the individual project manager's point of view. Consequently, the project has been conceptualised as a lonely phenomenon, independent of history, contemporary context and future. In other words, the shadow of the past, simultaneous events, and the shadow of the future are seldom included in the analysis. From a social science perspective, one would argue that it seems that the so-called closed system approach is dominant in 'traditional research and management of projects.

Interestingly, the same social sciences have a quite long tradition in the so-called open system approach in which units interact with their environment. This is the case for the economic sciences in which firms regularly interact with their environment (Lumpkin & Dess, 2001) to acquire resources (e.g., raw material, labor), to sell their output to other firms or to end users, or to compete with other firms from the same or other industries. It is also the case for the organisation sciences, in which several scholars theorised about the organisation - environment connection (e.g., resource dependence theory or transaction cost theory).

More recently, an increasing number of scholars have stressed that projects and project-based organisations are influenced by the organisational, relational, and institutional structures in which they are embedded (Manning & Sydow, 2011; Grabher, 2004). Additionally, participants in projects more often come from different organisations, and are characterised by higher diversity (e.g. in terms of knowledge base and cultural background). Furthermore, project-based organisations run multiple projects sequentially or simultaneously in which external partners participate more frequently. In sum, all of this shows that projects and their members are embedded in multiple contexts.

These developments pose interesting challenges to project management scholars and practitioners and even might have implications for the training of (young) people in general. Starting at the macro level one could pose the question: If projects and project-based organising are so pervasive in society, should the training of young people not be directed at learning the principles of project-based working? The fact that project-based organisations run multiple projects at the same time puts the governance and management of these portfolios of projects directly on the table (meso level). The management of individual project members needs new attention as well (micro level). For example, should project members be stimulated to develop ties with other project members or should project managers put in place incentives to increase tie formation with a person external to the project team. The former may be beneficial to team cohesion, whereas the latter may positively influence the project team's innovation output. Another managerial challenge pertains to the number of project teams in which employees should be allowed to participate. If employees can be part of several projects, how should their work be coordinated and to what extent can they effectively contribute to the goals of the project and the organisation. Project managers also have to pay attention to processes evolving inside projects and between project members. Does every type of conflict or disagreement between project members ask for managerial intervention? If so, what interventions are helpful?

It is one of the tasks of academic scholars to answer these and similar questions. In this way, evidence-based interventions can be developed and tested. The contributions to this special edition, introduced in the next section, hopefully form a step toward this goal.

4 Organisation of the special edition

This special edition of the South African Journal of Economics and Management Sciences brings together scholars from three continents and all interested in project-based organisation and its management. Their contributions aim to shed light on the relationships between the embeddedness of projects and the management of projects at different levels of analysis. The articles take a variety of approaches: conceptual, a literature review, empirical with small (case study) and large N research designs. Table 2 shows how each paper is positioned relative to the topics of project embeddedness, project management and its level of analysis.

In their leading article for this special edition, Packendorff and Lindgren propose that an increased focus on the processes of projectification would be beneficial to project research. They introduce a distinction between narrow and broad conceptualisations of projectification. Using this distinction and taking a macro perspective, they extend this research area from its current concern with the increased primacy of projects in contemporary organisational structures, into an interest for cultural and discursive processes in society in which notions of projects are invoked. One of the implications of their argument is that project-based organisation and project management are regarded as ideal and form a norm in organisations, societal life and in private life.

Bekker's paper is a review of the literature on project governance, which can be regarded as a meso analytical perspective since it takes a managerial perspective on multiple intra- and inter-organisational projects. It categorises the project governance literature into three schools of thought. From these schools of thought it can be concluded that the definition of project governance is a function of stakeholder complexity and functional positioning in the organisation. The development of project governance frameworks could also consider the complexity of projects spanning across international companies, across country borders and incorporating different value systems, legal systems, corporate governance guidelines, religions and business practices. Such frameworks stress the notion that projects are embedded in wider environments.

Jerbrant argues that many project-based organisations have to manage multiple projects simultaneously and she maintains that the classical view of multi-project management does not capture its dynamic nature. Present theory falls short in the expositive dimension of how management of project-based companies- evolves because of the need to be agile and adaptable to a changing environment. The purpose of her paper is therefore to present a descriptive model that elucidates the maturation processes in a project-based organisation, as well as to enhance understanding of multi-project management in practice. The maturation model displays how the management of project-based organisations evolves between structuring administration and managing uncertainty. It also emphasises the importance of active individual actions and situated management actions that have to be undertaken in order to coordinate, synchronise, and communicate the required knowledge and skills. With this specific form of project embeddedness, a project is surrounded by other projects, therefore requires a different type of project management in which a project portfolio is taken into account. The arguments developed in this paper also fit well into a discussion in which it is proposed that projects are both instrumental as well as social processes (Winter et al., 2006).

Van Kessel et al's. paper examines the relationship between perceptions of organisational culture, academics' social embeddedness, and their creative paper project output. It argues that the extent to which researchers working on paper projects are socially embedded by social ties with colleagues inside and outside their academic department (within the same university) is a causal step linking organisational values and norms to creative outputs. Basically, this study concludes that "no creative person and no project is an island" (also see: Engwall, 2003).

Chan observes that employees of project-based organisations are increasingly involved in more than one project team. This implies that an employee simultaneously has multiple memberships in these project teams, a phenomenon known as multiple team membership. Previous predominantly theoretical studies have acknowledged the impact that multiple team membership has on performance, but very limited empirical evidence exists. The aim of her study is to provide empirical support for some of these theoretical claims using South African team data. Her study shows that there are considerable performance- effects when an individual is embedded in more than one team.

With the micro perspective of individuals embedded in projects teams, Chang and Yeh develop and examine a model of the antecedents and consequences of decision-making comprehensiveness during the new product development process. This model firstly suggests a concave relationship between intrateam task disagreement and decision-making comprehensiveness. It also conjectures that conflict communications influence the effectiveness of decision-making comprehensiveness on new product project teams' performance. An empirical test of the proposed framework involves a survey of 220 cross-functional new product project teams. Some managerial and research implications of the findings are also discussed in this paper.

We hope that this special edition of the South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences fuels the discussion on project-based organising, project management and their links.

References

BAKKER, R.M. 2010. Taking stock of temporary organizational forms: A systematic review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(4):466-486. [ Links ]

EISENHARDT, K.M. & TABRIZI, B.N. 1995. Accelerating adaptive processes - product innovation in the global computer industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(1):84-110. [ Links ]

ENGWALL, M. 2003. No project is an island: linking projects to history and context. Research Policy, 32(5):789-808. [ Links ]

GANN, D.M. & SALTER, A.J. 2000. Innovation in project-based, service-enhanced firms: the construction of complex products and systems. Research Policy, 29(7-8):955-972. [ Links ]

GOODMAN, R.A. & GOODMAN, L.P. 1976. Some management issues in temporary systems: A study of professional development and manpower-the theatre case. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(3):494-501. [ Links ]

GRABHER, G. 2004. Temporary architectures of learning: Knowledge governance in project ecologies. Organization Studies, 25(9):1491-1514. [ Links ]

HANISCH, B. & WALD, A. 2013. Effects of complexity on the success of temporary organizations: Relationship quality and transparency as substitutes for formal coordination mechanisms. Scandinavian Journal of Management (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2013.08.005). [ Links ]

HOBDAY, M. 2000. The project-based organisation: An ideal form for managing complex products and systems? Research Policy, 29(7-8):871-893. [ Links ]

JONES, C. 1996. Careers in project networks: The case of the film industry. In M. Arthur & D. Rousseau (eds.) The boundaryless career: 58-75. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

KENIS, P., JANOWICZ-PANJAITAN, M.K. & CAMBRÉ, B. 2009. Temporary organizations: Prevalence, logic and effectiveness. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

LUMPKIN, G.T., DESS, G.G. 2001. Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(5):429-451. [ Links ]

MANNING, S. & SYDOW, J. 2011. Projects, paths, and practices: sustaining and leveraging project-based relationships. Industrial and Corporate Change, 20(5):1369-1402. [ Links ]

MAURER, I. 2010. How to build trust in inter-organizational projects: the impact of project staffing and project rewards on the formation of trust, knowledge acquisition and product innovation. International Journal of Project Management, 28(7):629-637. [ Links ]

PRENCIPE, A. & TELL, F. 2001. Inter-project learning: processes and outcomes of knowledge codification in project-based firms. Research Policy, 30(9):1373-1394. [ Links ]

RAAB, J., SOETERS, J., VAN FENEMA, P.C. & DE WAARD, E.J. 2009. Structure in temporary organizations. In: Kenis, P., Janowicz-Panjaitan, M.K. & Cambré, B. (eds.) Temporary organizations: prevalence, logic and effectiveness. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar:171-200. [ Links ]

SORENSON, O. & WAGUESPACK, D.M. 2006. Social structure and exchange: self-confirming dynamics in Hollywood. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51(4):560-589. [ Links ]

SYDOW, J., LINDKVIST, L. & DEFILLIPPI, R. 2004. Project-based organizations, embeddedness and repositories of knowledge: Editorial. Organization Studies, 25(9):1475-1489. [ Links ]

WINTER, M., SMITH, C., MORRIS, P. & CICMIL, S. 2006. Directions for future research in project management: the main findings of a UK government-funded research network. International Journal of Project Management, 24(8):638-649. [ Links ]