Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versión On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.16 no.5 Pretoria 2013

A study of Chinese guanxi type in family business from the perspective of power-based and leadership behaviours

Hsien-Tang TsaiI; Tung-Ju WuI; Shang-Pao YehII, *

IDepartment of Business Management, National Sun Yat-Sen University, Taiwan

IIDepartment of Tourism, I-Shou University, Taiwan

ABSTRACT

In Chinese society, a guanxi network is based on kinship or family ties of affection. This special pattern has a historical background and is one of the important factors that have enabled many Taiwanese enterprises to continue operating through the decades. The personal links between people create a kind of social network known as guanxi, which is a unique characteristic of Chinese society. The study aims to investigate the guanxi type of managers in Taiwanese family businesses, and examines how the guanxi type may moderate the correlation between the managers' power and the influence tactics used to handle subordinates. We surveyed 178 managers who are working in Taiwanese family business. The results of the hierarchical regression modeling showed that as managers have more position power, especially those exercising the family guanxi, they are more likely to be assertive in their treatment of their subordinates. Managers possessing the friend guanxi often play a bridging role to complement the function of those managers with the family guanxi, who may use the assertive approach too strongly. Managers of this type can provide a "lubricant effect" and keep the family business running smoothly. We recommend that family business owners should pay more attention to relationship harmony and internal communication channels in their organisations.

Key words: family business, guanxi, guanxi type, power based, position power, personal power, influence tactics, assertiveness, favour exchange, resource-based view

1 Introduction

The family business is a common type of organisation model (Burkart, Panunzi & Shleifer, 2003). In Taiwan, 80 per cent of enterprises follow the family business model. In Europe, this type of enterprise also represents 52 per cent of all businesses, and in the Netherlands, Germany and Austria the proportion of family-run enterprises in the business sector is also over 80 per cent (Donckels & Frohlich, 1991). Among the top companies in the US Fortune 500 rankings, almost one-third belong to family-run enterprises (Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2004). In Taiwan, more than 30 of the top 50 business groups use the family business model where family members have a major shareholding in the corporate equity. Research reports have found that the consolidated total global assets of the 100 largest groups in Taiwan exceeded NTD 50 trillion in 2009, and the earnings per share also increased by nearly 100 per cent compared with the 2008 EPS (CCIS, 2010). This shows that Chinese family businesses play a pivotal role in Taiwan's economic development. Gomez-Mejia, Larraza-Kintana and Makri (2003) suggest that family businesses must satisfy two requirements:

1) two or more executives of the enterprise must come from the family that owns the business; and

2) members of the family owning the business should hold more than 5 per cent of the enterprise's total equity.

However, Bartholomeusz and Tanewski (2006) argue that the criteria for a family business are that the key managers or principal members of the board of directors should be core members of the family that owns the business and that more than 40 per cent of the company shares should be held by close relatives of that family. Their definition of a family business therefore corresponds to those of previous scholars, who derive their proposed definitions from the perspectives of management and ownership.

In Chinese society, a guanxi network is based on kinship or family ties of affection. This special pattern has a historical background, and is one of the important factors that have enabled many Taiwanese enterprises to continue operating through the decades. To perform the tasks assigned to them by the organisation, managers need to have enough power to function in a leadership role and influence their subordinates. To this end, the organisation formally transfers power to the managers according to the structure of the family business to allow the managers to carry out their duties successfully. If the social structure changes, the family business would attempt to cope with the new situation by devising a cross-shareholding scheme for all affiliated companies. After the organisational restructuring, the key positions or posts that carry responsibility for making decisions are still held by the family members (blood relatives, relatives by marriage or friends), or else by confidants of the original family. However, matters such as the management of the relationship between family affairs and business, distribution of responsibilities and separation of powers gradually surface and become challenging issues for the family business.

Managers need to take certain actions to influence the behaviour of subordinates in an organisation so that they complete the tasks assigned to them by the organisation. Managers have to use influence tactics to change the behaviour of other persons (Durbin, 2001). Influence tactics are a means of influencing other people into cooperating or complying with one's demands. These tactics can change the attitudes, values, beliefs or behaviours of others. Managers are able through influence tactics (such as setting an example, commanding or lobbying) to influence people to attain organisational goals. More importantly, the effective use of influence tactics is often looked upon as an important criterion for evaluating a manager's leadership. It determines whether the manager's leadership is successful or not, and whether the results are immediately reflected in the performance of the whole organisation.

In Chinese society particular emphasis is placed on personal guanxi. From society as a whole down to organisation level, and from government officials to the general public, this kind of guanxi is ubiquitous (Jacobs, 1979; Tsai, Yeh & Wu, 2011). In fact, this personal guanxi is viewed as an asset in Chinese society, as it can determine the survival of an individual or a corporate entity. Therefore, differentiating between the guanxi types is the most important challenge for someone possessing power (Hwang, 1987). Summing up the above, personal guanxi may be used either for one's own protection, or to obtain rare resources so as to get ahead of the competition, or to be free from threats. Under the influence of cultural background and family heritage, a Chinese family business often prefers to have their children or descendants as future successors in their business.. This is known as family guanxi.

In a typical family business, most key positions or management posts that carry important decision-making authority are held by family members, but not all positions are filled by close relatives of the family owning the business. In fact, past literature has tried to break down personal guanxi into three types, namely family guanxi, friend guanxi and favour exchange guanxi (Hwang, 1987; Zhang & Li, 2003; Taormina & Gao, 2010). Although researchers have highlighted the relationship between managerial power and influence tactics (Kipnis, Schmidt & Wilkinson, 1980; Yukl, 2002), follow-up studies have not been able to identify any differences between different guanxi types and this relationship. Therefore, the first purpose of this study is to determine whether managers with different guanxi types in the family business show any differences in the way they use influence tactics to handle subordinates. And the second purpose is to explore how managers lead their subordinates and influence their behaviour in a family business, although they have different power bases and guanxi types.

2 Literature review

2.1 Guanxi

In Chinese society, the personal links between people are a kind of social network known as guanxi, a unique characteristic of Chinese culture. This culture emphasises the values of "collectivism" and "order", which are derived from Confucianism. It emphasises the role of individuals in the community and also provides the rules of conduct for getting along with other people. These personal connections which regulate relations with other people are called guanxi (Hwang, 1987; Yang, 1994; Tsai et al., 2011) and have gradually evolved to become an important value system in Pan-Asia. Personal guanxi of this nature in Chinese society may be referred to as social connections, but it should be remembered that personal guanxi is based on shared interests or mutual benefits for both parties (Tsai et al, 2011).

As a source of advice or assistance in solving problems, family members are the most direct and important group for an individual (Hwang, 1987; Zhang & Li, 2003). Yang (1994) proposed three types of guanxi depending on the closeness of the relationship, including family guanxi (the relationship between family members), acquaintance guanxi (the relationship between neighbours or colleagues) and stranger guanxi (pure acquaintances or social relations with no lasting nature). Taormina and Gao (2010) further transformed different guanxi patterns into behaviour patterns and called them guanxi behaviour, which includes family guanxi, friend guanxi and favour exchange guanxi. When an individual seeks help from other people, the first group that comes to mind is typically his family, and the second choice would be to turn to close friends.

The guanxi network is not restricted to direct links, and it may be established by reciprocity or cooperation so as to make the guanxi closer, until it reaches acceptable targets. Renqing is found to be an important element in maintaining personal guanxi (Lee, Pae & Wong, 2001; Lee & Dawes, 2005; Zhuang, Xi & Tsang, 2010). Renqing may be established through social interaction so that people with no kinship or different social backgrounds are linked together. After sustained social interaction, mutual feelings become warmer with time. However, there are two important factors which help to maintain personal guanxi, namely trust and reliability.

2.2 Power base

Power can be viewed as a unique resource of an individual; it refers to the ability to manipulate someone or something. Power is an interactive relationship; it means that a person has the resources needed by others, so that person is able to control/influence his behaviour or attitudes. Finkelstein (1992) believed that when managers are faced with strategic decision making, the application of power becomes a very crucial factor in the process.

French and Raven (1959) referred to five different types of power base in describing a manager's leadership of subordinates. These types include legitimate (the formal authority given to a person through the organisation because of an official position), reward (the power to allocate valuable rewards to other persons), coercive (the power to punish other persons), expert (the power entrusted to a person by the organisation based on their special skills or professional knowledge), and referent (the influence that results from unique personal characteristics that make other people ready to follow). The study by Rosenberg and Pearlin (1962) found that a manager's power will gradually evolve, depending on their job level and tenure. More experienced managers in an organisation prefer to use legitimate and referent techniques to get along with others. Some scholars contend that the expert and the referent types of power base are derived from exclusive personal characteristics, but legitimate rights and reward rights arise from formal authority conferred through the organisation (Robbins, 2001; Yukl, 2002), and have therefore tried to condense the five types of power base into two categories, namely position power and personal power.

Garcia, Restubog and Denson (2010) say that the family is the most important influence in one's life, so when one needs outside help, the first choice is a family member and the second a close friend (Taormina & Gao, 2010). Organisations usually assign dissimilar levels of power to managers, based on their responsibilities or required expertise (Robbins, 2001), but the Chinese family business is a special case. The core power is mostly held by family members or close friends, so the managers possessing family guanxi usually have more power than others. This study therefore concluded that managers possessing family guanxi, as opposed to managers possessing favour exchange guanxi, have more position power. On the other hand, managers possessing favour exchange guanxi, as opposed to managers possessing family guanxi, have more personal power. Based on the foregoing, our first hypothesis is:

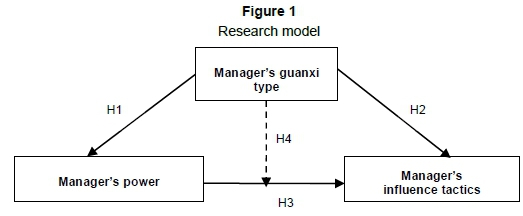

H1: There is a significant difference between managers' power and their guanxi types in the family business.

2.3 Influence tactics

The actions taken by managers to influence the behaviour of subordinates are called influence tactics Influence is an important means of persuading other people to believe or engage in certain behaviour. The most important function in leadership is to influence others in the organisation to attain the desired target, and managers use various influence tactics to achieve the objectives. Yukl and Falbe (1990) believed influence to be a bridge that is an important means of linking power and goals. The choice of influence tactics varies according to the purpose and applications, and three categories can be distinguished: upward, horizontal and downward tactics.

In an organisation, relationships can be divided into vertically oriented top-down relationships and laterally oriented relationships with colleagues. However, in Chinese enterprises, subordinates are subjected to deep influence from the boss in both their working lives and their private lives, so vertical top-down relationships between supervisors and subordinates are far more important than the laterally oriented relationships with colleagues. Kipnis et al. (1980) and Schriesheim and Hinkin (1990) attempted to classify influence tactics into six types: Ingratiation: showing goodwill and currying favour first and then revealing intentions; Exchange: exchange of desired benefits; Rationality: proposing logical and rational ideas based on the facts presented; Assertiveness: taking direct and tough action, for example, ordering other people to comply with the regulations set; Upward appeal: seeking help from superiors; and Coalition: seeking support from other people within the organisation. Research by Yukl and Falbe (1990) found that the most commonly used tactic for exerting influence over the subordinates is rationality and coalition is found to be the least effective.

Because the managers in the organisation may come from different guanxi types, their management or leadership styles will be different. From the point of view of resources, power is a scarce resource. If the manager is a relative of the family owning the business, he will be given more power and special preferences, so he will probably adopt tougher management behaviour. On the other hand, if the manager only has favour exchange guanxi in a family business, he may adopt a more conservative approach to managing subordinates. This study deduced that managers possessing family guanxi tend to use more rigid influence tactics in managing subordinates, such as assertive tactics; besides, the managers possessing favour exchange guanxi tend to use more affable influence tactics to manage subordinates, such as ingratiation and exchange tactics. Therefore, our second hypothesis is:

H2: There is a significant difference between managers' influence tactics and their guanxi types in the family business.

Brass and Burkhardt (1993) believed that influence tactics are derived from power and there is a significant correlation between the two. Yukl (2002) suggests that the influence tactics adopted by managers may depend on different objects or positions, and can strengthen the way they intend to use their influence. Hence, when the managers have diverse sources of power, their leadership behaviour and influence tactics regarding subordinates will be different. In the family business, the managers with more formal position power conferred through the organisation are able to take a tougher leadership stance in asking the subordinates to perform certain tasks, so they are inclined to use more assertive and less affable approaches in management. Furthermore, the managers have more personal power owing to their own professional or personality traits, and tend to lead the subordinates with ingratiating or exchange approaches, and use less assertive approaches. We suggest that in the Chinese family business, the managers possessing more position power are more likely to use an assertive approach in managing subordinates; and the managers possessing more personal power are more likely to use an affable approach. Therefore, our third hypothesis is:

H3a: Position power and assertive tactics are positively related to each other.

H3b: Personal power and influence tactics, including ingratiation, exchange, rationality, upward appeal and coalition, are positively related to each other.

Business guanxi and family guanxi are vastly different concepts (Hwang, 2009). Business guanxi generally refers to gift giving, bribery and other informal favour exchanges, whereas family guanxi mainly emphasises the obligation of reciprocal assistance. Both types of guanxi are found in Chinese family businesses. Since most of the key positions with decisionmaking power are held by close relatives of the business, a manager's identity and guanxi type are important considerations when assigning power or key positions in a family business. We have found that managers in family businesses are not only family members but may also be friends or persons with favour exchange guanxi. However, to consolidate their ownership and to make the operation run smoothly, managers in the family business are assigned necessary powers, depending on their guanxi type, to protect rare resources, which is the reason for different leadership behaviour towards subordinates. Compared to managers possessing (friend) favour exchange guanxi, managers possessing family guanxi usually have more position power, so their leadership behaviour is more assertive. Since managers possessing favour exchange (friend) guanxi have more personal power than managers possessing family guanxi, they are more inclined to choose ingratiation, exchange, rationality appeal, upward appeal and coalition tactics. Therefore, the fourth hypothesis is predicated as follows:

H4a: There is a moderation effect between position power and assertiveness for managers possessing family guanxi.

H4b: There is a moderation effect between personal power and influence tactics, including ingratiation, exchange, rationality, upward appeal and coalition, for managers possessing favour exchange guanxi.

3 Research design

3.1 Sample

There were 112 family businesses participating in this study and each of them received two to five questionnaires, to be distributed to the managers in the sample. A total of 192 questionnaires were sent, and 178 valid returned questionnaires were received.

The managers in the sample were male (64.6 per cent), middle-level managers (44.4 per cent) with a mean age of 35.2 years. Their professional duties mainly relate to general affairs (31.5 per cent) and marketing (25.3 per cent). Most managers have family guanxi (41 per cent) with executives in the family business. The second most prevalent is friend guanxi (34.3 per cent) and the last favour exchange guanxi (24.7 per cent).

3.2 Variable definition

3) Power base

We adopted Hinkin and Schriesheim's (1989) Bases of Social Power Questionnaire and revised the content into 20 questions with a 5-point scale. According to Yukl's (2002) suggested procedure, we condensed the five categories of power base into two categories, namely position power and personal power. The Cronbach's α for this section is 0.912.

4) Influence tactics

We used the theory of Kipnis et al. (1980) which identifies various influence tactics, including ingratiation, exchange, rationality, assertiveness, upward appeal and coalition. The measurement table that we designed contains 18 questions based on a 5-point scale. The Cronbach's α for this section is 0.887.

5) Manager's guanxi type

The manager's guanxi type is a categorical variable that includes three types of guanxi: family guanxi, friend guanxi and favour exchange guanxi. Before performing regression analysis, we used two dummy variables as stand-ins. In the case of family guanxi, the variable value is set at 1, and at 0 for other guanxi. In the case of friend guanxi, the variable value is set at 1, and at 0 for other guanxi.

6) Control variables

Based on previous family business and guanxi studies (Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2004; Chung, 2012), the manager's background is regarded as providing the control variables in this study. These variables are: the manager's gender (1 for "male"; 0 for "female"), years of service (1 for "10 years or more"; 0 for "less than 10 years"), job function (1 for "operation units including production and development, and sales units"; 0 for "non-operating units including financial, general affairs and information departments"); job level (1 for "middle-level or higher level manager"; 0 for "basic manager") and industry (1 for "manufacture"; 0 for "non-manufacture").

Verification and analysis

The common method variance (CMV) may inflate or deflate the statistical results in the current study (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee & Podsakoff, 2003). Therefore, we used Harmen's single-factor analysis to test for the presence of the CMV. The results showed that 11 factors are produced, in which the first factor has a cumulative explained variance of 17.14 per cent and does not concurrently contain independent and dependent variables.

The means, standard deviations and correlation coefficients among focused variables are listed in Table 1. The ANOVA results showed that managers who possess dissimilar guanxi types have different types of power and use various influence tactics to manage their subordinates. As listed in Table 2, compared with other guanxi, the managers possessing family guanxi tend to have more position power, and the managers possessing favour exchange guanxi tend to have more personal power. Regarding ways of managing subordinates, the managers possessing favour exchange guanxi are more likely to use ingratiation and exchange tactics compared with those managers who possess friend and family guanxi. The managers possessing family guanxi are more likely to use assertive tactics compared with other guanxi types. Therefore, our hypotheses 1 and 2 are supported.

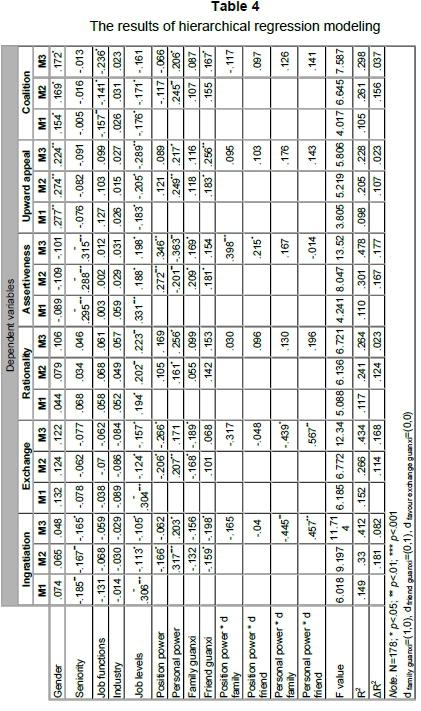

Before performing the hierarchical regression, we set up the control variables as the first step, and the results of the analysis are shown in Table 3. The results showed that the managers with more position power in the family business are more likely to use assertive tactics in managing their subordinates (β =.331, P <.001), and they are less likely to use ingratiation (β = -.215, P <.01) and exchange tactics (β = -.238, P <.01). However, the managers with more personal power in the family business are more likely to use ingratiation (β =.334, P <.001), exchange (β =.232, P <.01), rationality (β =.146, P <.05), upward appeal (β =.249, P <.01), and coalition (β =.244, P <.01), and they are less likely to use assertive tactics (β = -.232, P <.001). Thus, our hypothesis 3 is supported.

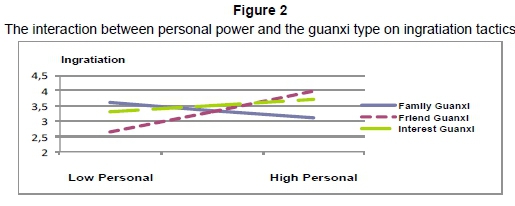

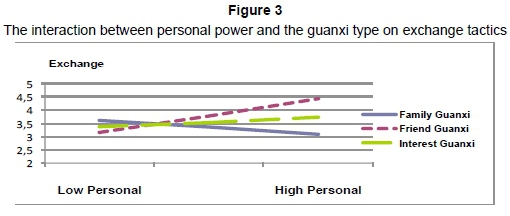

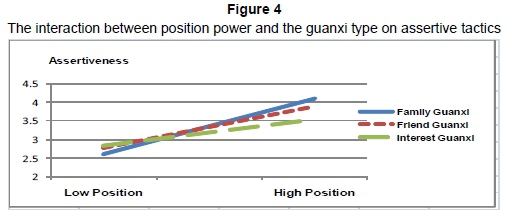

We followed the suggestion of Baron and Kenny (1986) in testing hypothesis 4. We set the guanxi type as a moderating variable, and the result is shown in Table 4. We found that managers possessing family guanxi (β = -.445, Ρ <.001) have more personal power, compared with those managers who possess favour exchange guanxi, and they are less likely to manage subordinates with ingratiation. On the other hand, the managers possessing friend guanxi (β =.457, Ρ <.001) are more likely to use ingratiation, as shown in Figure 2. Similarly, when the managers possessing family guanxi (β = -.439, Ρ <.01) have more personal power, compared with those managers possessing favour exchange guanxi, they are less likely to use exchange tactics in managing subordinates. The managers possessing friend guanxi (β =.457, Ρ <.001) are more likely to use exchange tactics, as shown in Figure 3. Finally, when managers possessing family guanxi (β =.398, Ρ <.001) and friend guanxi (β =.215, Ρ <.05) have acquired more position power, they are more likely to manage subordinates with assertive tactics, as shown in Figure 4. Therefore, our hypothesis 4 is supported.

5 Conclusions

The family business plays an important role and is a common type of enterprise in Chinese society. Because most important positions within the organisation are held by close relatives or friends, there are bound to be some communication problems between the supervisor and the subordinates. Therefore, the management of the relationship between family affairs and business, the division of power, and the allocation of responsibilities all become important issues in such an organisation. The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between managers' power, influence tactics and guanxi type. The current study found that the managers' power in a family business may depend on different guanxi types, with resultant differences in leadership behaviour by managers. We therefore make some suggestions based on the research findings with respect to future managers' job assignments in the family business.

According to the results of this study, most of the managers in positions of power are key family members and those managers who possess favour exchange guanxi often have more personal power. The managers who possess favour exchange guanxi are more likely to use ingratiation and exchange tactics to influence subordinates, as opposed to those managers who possess family guanxi. The managers who possess friend guanxi are more inclined to use upward appeal tactics, as opposed to those managers who possess favour exchange guanxi. The managers possessing family guanxi are more likely to use assertive tactics to influence their subordinates, as opposed to those with favour exchange guanxi.

Since the managers possessing family or friend guanxi have a special, unique relationship with the family that owns the business, as opposed to those managers possessing favour exchange guanxi, as Hwang (2009) noted, this type of close relationship allows the managers to hold more privileges or receive special care. Managers with this type of guanxi are often regarded as heirs to the future business, hence the organisation will often confer a lot of authority on these managers. When they deal with subordinates, they often ignore the feelings of the subordinates, and use an assertive approach when asking other people to do what they want. In contrast, the managers possessing favour exchange guanxi, as opposed to those with family guanxi, are likely to manage subordinates with more empathy, so they are more likely to use more unassuming or ingratiating exchange tactics to influence subordinates.

This study also found that if the managers possessing family guanxi have acquired more position power, they are more inclined to use assertive tactics rather than ingratiation and exchange tactics. Because the managers possessing family guanxi have formal power conferred on them by the organisation, these managers are inclined to adopt a more straightforward and tougher management style in leading their subordinates, and are less likely to use more pacific approaches. On the other hand, the managers who have more personal power are likely to adopt a more affable attitude when influencing subordinates, such as through ingratiation, exchange and rationality appeal or coalition tactics. Because personal power is derived from special personal traits or professionalism, managers with personal power may lead subordinates according to their professional judgment. In exercising their leadership role, managers of this type are more agreeable and affable towards their subordinates. They tend to help their subordinates from a professional standpoint with the intention of working together to attain the objectives of the organisation.

Finally, the interaction effect between different power and influence tactics revealed several interesting aspects. First, as seen from Figures 2 and 3, because of the special status and relationship with the family business, if the managers possessing family guanxi have acquired more personal power, they are less likely to use ingratiation and exchange tactics on their subordinates. Another point worth mentioning is that when managers possessing friend or favour exchange guanxi have acquired more personal power, they are more likely to use ingratiating and exchange tactics. This study has attempted to use a resource perspective to explain the research findings. Managers possessing family guanxi possess certain resources that others do not have at the outset, because of the special relationship with the family business (i.e. kinship), so these managers are more likely to be arrogant in front of their subordinates. Therefore, considering the minzi element, these managers are less likely to use a more agreeable approach in dealing with subordinates.

In contrast, the managers who possess friend guanxi entered the organisation through informal channels (interview), based on their special guanxi with the family business, and are more aware of the importance of maintaining good relationships. In order to consolidate their positions in the organisation, they tend to use ingratiating means and exchange tactics to curry favour with subordinates in an effort to maintain good relations with them. Therefore, these managers are able to obtain more resources from the organisation. As shown in Figure 4, once managers who possess family guanxi have acquired more position power, as opposed to the other two types of managers, they are more likely to use assertive tactics in managing subordinates. The managers possessing family guanxi are working in their own business, and they often exhibit a sense of superiority in front of other people because they know that their family will stand behind them and support them. If the managers who possess family guanxi are able to obtain more position power, they tend to indulge in self-satisfaction on account of the power they possess. This makes it more difficult to lead subordinates with empathy, and they are more likely to adopt an assertive approach when asking the subordinates to do things, thus deepening the distrust between the managers and their subordinates.

The influence tactics chosen by the managers not only have to fulfil their own purpose, but also need to achieve the overall objectives of the organisation. Therefore, managers need to make good use of the powers conferred on them by the organisation. They should make more frequent use of the tactics that can produce good emotional support or lobbying, so as to make it easier for the subordinates to understand the missions and their value to the organisation. This would establish the necessary mutual trust between the two parties. They should make less use of the authoritative approach to force other people to comply, so as to avoid rebellion on the part of subordinates, which would affect the realisation of the organisation's objectives.

Since the managers who possess family guanxi have strong ties with the family business, and are often regarded as the corporate successor, it is no surprise that many important positions in the organisation are held by them. When they propose to do something, they are less likely to take the feelings of subordinates into account. This could easily produce a communication breakdown between the manager and subordinates, which could lead to estrangement. We suggest that if the managers possess friend guanxi, because of the special relationship with the supervisor, they will function more like a "bridge" or have a "lubricant" effect. Because of their harmonious friendship with the corporate management, these managers tend to treat subordinates in a more affable manner and complement the managers who possess family guanxi in establishing cordial relations with subordinates or listening to employees. Therefore, company policies can be implemented smoothly, and tasks assigned by the organisation can be performed well as a result of good cooperation.

Finally, in this relatively conservative and closed management environment we suggest that business owners need to pay more attention to communication between the supervisor and the subordinates. Job assignment for managers should also be monitored, so that it can help achieve the objectives of the organisation, enhance job performance by subordinates, and maintain good relations between supervisors and subordinates. This would enable the operation of the family business to be carried out more smoothly. A suggestion for future research is more in-depth research to explore performance, job commitment or job innovation for managers with a different guanxi type, to complement the current research and make up for any inadequacies.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the valuable comments made by the reviewers.

References

BARTHOLOMEUSZ, S. & TANEWSKI, G.A. 2006. The relationship between family firms and corporate governance. Journal of Small Business Management, 44(2):245-267. [ Links ]

BARON, R.M. & KENNY, D.A. 1986. The moderator-mediator variables distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6):1173-82. [ Links ]

BARSADE, S.G., WARD, A.J., TURNER, J.D.F. & SONNENFELD, J.A. 2000. To your heart's content: a model of affective diversity in top management teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(4):802-836. [ Links ]

BRASS, D.J. & BURKHARDT, M.E. 1993. Potential power and power use: an investigation of structure and behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 36:441-470. [ Links ]

BURKART, M., PANUNZI, F. & SHLEIFER, A. 2003. Family firms. Journal of Finance, 58:2167-2210. [ Links ]

CHINA CREDIT INFORMATION SERVICE. 2010. Top 10 largest business groups for 2010, showing that the financial industry is almost taking all away while the technology industry is giving all up! http://News.Cnyes.Com/Content/20101027/Kccbqbm8aqetq.Shtml. [ Links ]

CHUNG, H.M. 2012. The role of family management and family ownership in diversification: the case of family business groups. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Doi:10.1007/S10490-012-9284-X. [ Links ]

COSTA, P.T. & MCCRAE, R.R. 1985. The neo personality inventory manual. Odessa, Fl: Psychological Assessment Resources. [ Links ]

DONCKELS, R. & FROHLICH, E. 1991. Are family businesses really different? European experiences from Stratus, Family Business Review, 4(2):149-160. [ Links ]

DURBIN, A.J. 2001. Leadership: research findings, practice and skills (3rd ed.) Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

FINKELSTEIN, S. 1992. Power in top management teams: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 35:505-538. [ Links ]

GARCIA, P.R.J.M., RESTUBOG, S.L.D. & DENSON, T.F. 2010. The moderating role of prior exposure to aggressive home culture in the relationship between negative reciprocity beliefs and aggression, Journal of Research in Personality, 44(3): 380-385. [ Links ]

GOMEZ-MEJIA, L., LARRAZA-KINTANA, M., & MAKRI, M. 2003. The determinants of executive compensation in family-controlled public corporations, Academy of Management, 46(2):226-237. [ Links ]

FflNKIN, T.R. & SCHRIESHEIM, C.A. 1989. Development and application of new scales to measure the French and Raven (1959) bases of social power, Journal of Applied Psychology, 74:561-567. [ Links ]

HWANG, K.K. 1987. Face and favor: the Chinese power game. American Journal of Sociology, 92:944-974. [ Links ]

HWANG, K.K. 2009. Confucian relationalism: philosophical reflections, theoretical construction, and empirical research. Taipei: Psychological Publishers. (In Chinese) [ Links ]

JACOBS, J.B. 1979. A preliminary model of particularistic ties in Chinese political alliances: Kan-Ch'Ing and Kuan-Hsi in a rural Taiwanese township, The China Quarterly, 78:237-273. [ Links ]

KELLERMANNS, F.W., & EDDLESTON, K.A. 2004. Feuding families: when conflict does a family firm good. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(3):209-228. [ Links ]

KIPNIS, D., SCHMIDT, S.M. & WILKINSON, I. 1980. Intraorganizational influence tactics: explorations in getting one's way. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65(4):440-452. [ Links ]

LEE, D.J., PAE, J.H., & WONG, Y.H. 2001. A model of close business relationships in China (guanxi). European Journal of Marketing, 35(1/2):51-69. [ Links ]

LEE, D.Y., & DAWES, P.L. 2005. Guanxi, trust, and long-term orientation in Chinese business markets. Journal of International Marketing, 13(2):28-43. [ Links ]

LEWIN, K. 1938. The conceptual representation of the measurement of psychological forces. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

LUO, Y.D. 2007. Guanxi and Business. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing. [ Links ]

MITCHELL, R.K., MORSE, E.A. & SHARMA, P. 2003. The transacting cognitions of non-family employees in the family businesses setting, Journal Of Business Venturing, 18(4):533-551. [ Links ]

MOLLY, V., LAVEREN, E. & DELOOF, M. 2010. Family business succession and its impact on financial structure and performance. Family Business Review, 23:131-147. [ Links ]

MORCK, R. 2005. A history of corporate governance around the world: family business groups to professional managers. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

PERVIN, L.A. 1993. Personality: theory and research (6th ed.) New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

PODSAKOFF, P.M., MACKENZIE, S.B., LEE, J.Y. & PODSAKOFF, N.P. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5):879-903. [ Links ]

ROBBINS, S.P. 2001. Organizational Behavior (9th ed.) Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

ROSENBERG, M. & PEARLIN, L. 1962. Power-orientations in the mental hospital. Human Relations, 15: 335-349. [ Links ]

ROTTER, J.B. 1966. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General And Applied, 80(1):1-27. [ Links ]

SCHRIESHEIM, C.A., & HINKIN, T.R. 1990. Influence tactics used by subordinates: a theoretical and empirical analysis and refinement of the Kipnis, Schmidt and Wilkinson subscales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(3):246-257. [ Links ]

SPECTOR, P.E. 1982. Behavior in organizations as a function of employee's locus of control. Psychological Bulletin, 3:482-497. [ Links ]

TAORMINA, R.J. & GAO, J.H. 2010. A research model for Guanxi behavior: antecedents, measures, and outcomes of Chinese social networking. Social Science Research, 39(6):1195-1212. [ Links ]

TSAI, H.T., YEH, S.P. & WU, T.J. 2011. The use of governmental-firm Guanxi under different market conditions for Taiwanese hospitality firms invested in China. Actual Problems of Economics, 12(2):4-11. [ Links ]

YANG, C.F. 2000. Psychocultural foundations of informal groups: the issues of loyalty, sincerity, and trust. In Dittmer, H.F. & Lee, P.N.S. (eds.) Informal politics in East Asia. NY: Cambridge University Press: 85-105. [ Links ]

YANG, M.M. 1994. Gifts, favors and banquets: the art of social relationships in China. NY: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

YUKL, G. 2002. Leadership in organizations (4th ed.) Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

YUKL, G. & FALBE, C.M. 1990. Influence tactics in upward, downward, and lateral influence attempts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75:132-140. [ Links ]

ZEVON, M.A. & TELLEGEN, A. 1982. The structure of mood change: an idiographic/nomothetic analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(1): 111-122. [ Links ]

ZHANG, X., & LI, G. 2003. Does Guanxi matter to nonfarm employment? Journal of Comparative Economics, 31(2):315-331. [ Links ]

ZHUANG, G., XI, Y. & TSANG, S.L. 2010. Power, conflict, and cooperation: the impact of Guanxi in Chinese marketing channels. Industrial Marketing Management, 39:137-149. [ Links ]

* Corresponding author contact: Shang-PaoYeh, Shangpao@ms12.hinet.net