Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versión On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.15 no.4 Pretoria ene. 2012

ARTICLES

Exploring coping strategies of business leaders during an economic downturn

Marlise van Zyl; Yvonne du Plessis

Department of Human Resource Management, University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

As a large part of South Africa's economy is based on the mining industry, this research focused on exploring the coping strategies of business leaders in the mining industry during an economic downturn. Using qualitative research within a constructivist-interpretive paradigm, the researchers sought a deeper understanding of how mining leaders cope during an economic downturn. A purposive sample of seven executive mining leaders of different mining houses was interviewed and data was analysed using Atlas.ti. A conceptual framework for understanding coping strategies at the individual, group and organisational levels for business leaders during an economic downturn was developed and is discussed here. This study contributed to theory and practice by focusing on coping responses to specific situations within a specific context instead of on general coping strategies.

Key words: coping, economic downturn, business leaders, coping strategies

JEL: L200

1 Introduction

When the global crisis unfolded during 2008, it initially seemed that South Africa and other emerging market economies would be relatively unaffected. South Africa's banking system, according to the Head of Research and Policy Development at the South African Reserve Bank, 'was only marginally exposed to the sublime assets that initiated the crisis' (Kahn, 2009:22), with the result that commodity prices continued to increase in the first half of 2008.

This situation changed dramatically after September 2008, following the demise of Lehman Brothers, which led to the collapse in global confidence. This drastically decreased the capital available to emerging markets, coupled with a remarkable decline in commodity prices and a plunge in the demand for exports, particularly commodities from emerging markets (Kahn, 2009:22). However, until well into 2009, business and political leaders in South Africa seemed to 'languish in a state of denial' (Marais, 2010:s.p.), continuing to predict positive economic growth.

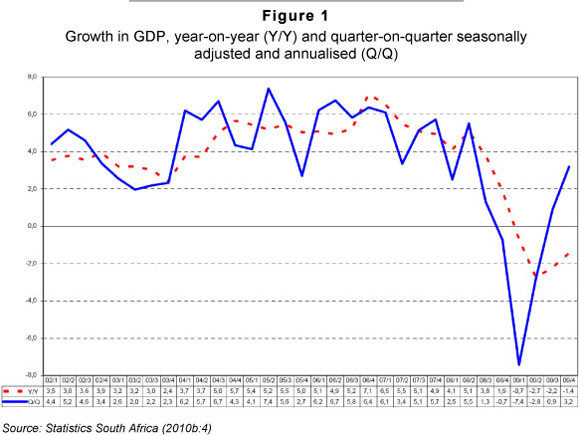

Nevertheless, South Africa did indeed experience its first official recession in 17 years in the first quarter of 2009, with a drop of 7.4 per cent in the country's gross domestic product (GDP) (Statistics South Africa, 2009: 4). It must be noted that all figures are seasonally adjusted to reflect real annualised changes from the previous quarter. The GDP continued its negative growth in the second quarter, contracting at a rate of 2.8 per cent, after which it recovered marginally to show a very slight positive growth rate of 0.9 per cent in the third quarter of 2009 (Statistics South Africa, 2010a). As shown in Figure 1 below, this positive growth rate continued in the fourth quarter of 2009.

As a large portion of South Africa's economy is based on the mining industry, this research focused on exploring the coping strategies of business leaders in the mining industry during an economic downturn.

In this paper we aim to discuss coping strategies that can be employed as a guiding framework for South African business leaders during an economic downturn. In order to reach this objective we have organised the paper as follows: first, we present an overview of the context of the study in order to clarify the research problem. We then discuss the research design and method, explaining the qualitative process and data-collection method used. This is followed by an outline of the data-analysis method used. The results and findings are discussed. We conclude by discussing possible limitations, practical and theoretical managerial implications and suggestions for future research.

1.1 Economic context in the mining industry

According to the Minister of Mineral Resources, Ms Susan Shabangu (2009:s.p.), the South African mining industry, which is responsible for more than half of the country's export earnings, was under particularly severe strain from 2008 to 2009. After a worldwide commodity price boom from 2003 to 2007, commodity prices declined drastically. This can be explained by the role of commodities as both a production input and a financial asset. A slowdown in global economic activities and the demand for commodities for production purposes, coupled with an increase in supply capacity, led to a decrease in prices. The financial crisis also contributed to the downward price momentum, as investors reduced their holdings of commodity assets (Southern African Resource Watch, 2009:4).

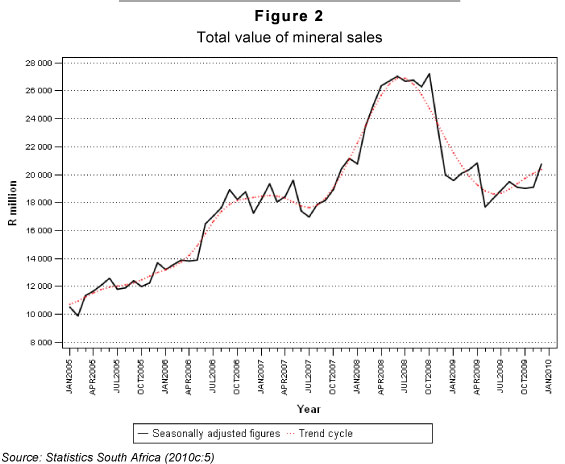

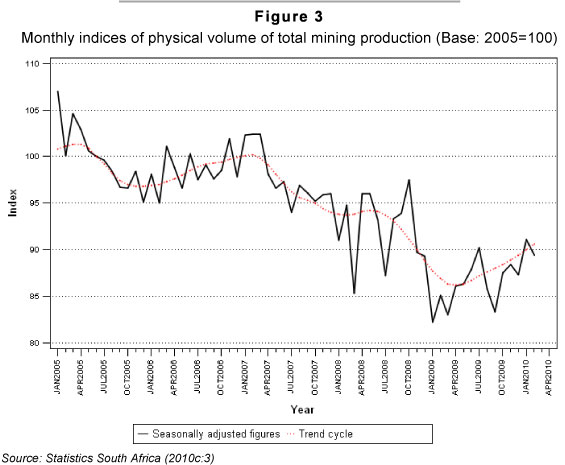

On the back of the drastic commodity price drop and the reduced value of mineral sales (Figure 2), mining houses reduced production, as indicated in Figure 3.

Mining is cyclical in nature and mining companies take a long-term view of their operations. However, historical evidence shows that, when a downturn looms, the first reaction of mining companies is to reduce costs by retrenching workers. This also proved to be the case during the downturn in 2009, when several mining organisations retrenched workers (Southern African Resource Watch, 2009:21).

With the mining sector declining by 32.8 per cent, the worst state of the industry since 1967 (Statistics South Africa, 2009:1), industry leaders faced a daunting challenge: how could they ensure that their company would weather the downturn? Mining houses around South Africa were cutting production and capital spending, retrenching employees, and restructuring, putting pressure on employee morale across their organisations, including executives.

With uncertainty about the depth, severity and duration of the downturn and its outcome, the mining industry and its leaders came under severe strain. An economic downturn has a severe impact on consumers, as well as a profound and far-reaching impact on the workplace (Naiman, 2009:49). Workplace morale typically goes into a downward spiral in response to the bombardment of negative information, job losses, fear and insecurity. Increased work demands compete for the attention of a distracted workforce; and managers, who are grappling with the same pressures as their staff, must somehow motivate people, not only to do their own jobs, but also often to take on the responsibilities of former co-workers (Naiman, 2009:49).

All of the above mean that business leaders must be able to cope if they are to manage in an economic downturn. The research questions for the study presented in this paper are:

- How do South African business leaders cope during an economic downturn?

- How could organisations assist South African business leaders to cope better during an economic downturn?

- What comprises a coping strategy framework for South African business leaders?

The next section explores the concept of coping and coping research, outlining trends in this field of research as well as criticisms against more traditional methods of coping.

1.2 Coping and coping research

Lazarus and Folkman (1984:147) define coping as the 'thoughts and behaviours that people use to manage the internal and external demands of situations that are appraised as stressful' . According to Folkman and Moskowitz (2004: 746), a large amount of coping research is based on Richard Lazarus's 1966 book Psychological stress and the coping process. Coping as a distinct field of psychology emerged during the 1970s and 1980s (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004:746); and coping research was greatly stimulated by the development of the 'Ways of coping checklist' developed by Folkman and Lazarus (1980, in Somerfield & McCrea, 2000:621). Hobfoll, Schwarzer and Chon (1998:181) argue that stress and coping are the most widely studied phenomena in psychology, identifying over 29 000 research articles on stress and coping over the period 1984 to 1998. A more conservative search by Somerfield and McCrae (2000:621), focusing primarily on coping behaviour and spanning the period 1967 to 1999, still produced 13 744 records.

Conversely, there is abundant criticism of coping research (see Somerfield & McCrae, 2000:621 for a review). Most of these critiques point out conceptual and methodological issues. In particular, measures to assess coping, particularly by means of checklists, are criticised; narrative approaches are suggested as an alternative to checklists (Lazarus, 2000:666; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004:750) to gain a deeper understanding of what an individual is coping with, especially when the stressful event is not a single event, such as coping with restructuring and organisational change. Narrative approaches are also useful in identifying and studying ways of coping that are not included in existing inventories (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004:751).

Coping is a process that unfolds in the context of a situation (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Somerfield and McCrae (2000:624) appeal to researchers to focus on coping responses to specific situations within a specific context, instead of focusing on general coping strategies. Folkman and Moskowitz (2004:768) suggest that new methodologies and new ways of thinking about coping within a specific context will help this field of study to mature. This is because the field holds great potential to explain who flourishes under stress and who does not, and it also has potential when it comes to interventions for helping people cope with stress. In line with this, this paper delineates a strategic coping framework for South African business leaders in the mining context, using more narrative methodologies than are traditionally employed in coping research.

2 Use of literature

Literature was used in this study for two main purposes. Firstly, it was used as an orienting process. According to Urquhart (2007:351), such a process allows the researcher to become aware of the current thinking in the field without taking a position regarding the research to be done. This approach was useful in 'nesting' the problem, a term used by Walcott (1990:17, in Silverman, 2005:299). Thus, part of the literature review was conducted prior to the data collection and data analysis, bearing in mind the reason for delaying a literature review, which is not forcing preconceived ideas onto the data.

Secondly, literature was used to explain data, showing the relevance of findings in relation to the existing body of knowledge (Henning, 2004:27). Stern (2007:123) uses the following quotation by Robert Burton (cited from Bartlett, 1980:258) to explain this eloquently: '... a dwarf standing on the shoulders of a giant may see farther than the giant himself.' Stern (2007:123) notes that, while you may feel like a giant when you develop theory, you are, in fact, a dwarf, which makes it important to position your work within the body of related literature. This is because, first, it is academically honest to do so and, second, it demonstrates how you have built upon it to enable you to see further.

3 Methodology

It is important to highlight the paradigm applied in this paper in order to place the research design, methodology and approach in context. This is to avoid the pitfall that Evered and Louis (1981:386) so aptly warn researchers against: often 'the quality of a piece of research is more critically judged by the appropriateness of the paradigm selected than by the mere technical correctness of the methods used'.

A constructivist-interpretive paradigm is applied in this paper. Interpretive research is based on the belief that a deeper understanding of a phenomenon is made possible only by understanding the interpretations of that phenomenon by those experiencing it (Shan & Corley, 2006:1823). The constructivist-interpretive perspective thus assumes that reality is constructed by the people (including the researcher) who participate in this reality. Constructivists acknowledge that their interpretation of the studied phenomenon is in itself a construction (Charmaz, 2006:187).

In line with the research paradigm, a qualitative research approach was deemed most suitable, owing to the intense and enduring complexity of the leadership phenomenon studied and the search for deeper meaning. Conger (1998) argues that qualitative research is the cornerstone methodology for understanding the 'how' and 'why' of leadership as opposed to its 'what', 'where' and 'when'.

3.1 Sampling

Purposive sampling was selected for this study as a sampling strategy. This selection was made based on the researcher's knowledge of the population, its elements and the purpose of the study (Babbie, 2007:184).

Sampling took place on an institutional level (mine), and on an individual level (mining leader). Based on the researcher's knowledge of the population and the purpose of the study, mines or mine groups were selected that are involved in beneficiating a variety of commodities, namely gold, platinum and uranium. Individual leaders (executives) within each company were then selected purposively from the executive committees to form the unit of analysis for this study. The sample size was seven mining leaders, who were determined by data saturation.

3.2 Data collection

Interactive interviews were used in this study. These were also referred under the term 'intensive interviewing' (Charmaz, 2006:25). This author refers to 'intensive interviewing' as permitting an in-depth exploration of a particular topic. It is thus useful for interpretive inquiry. The aim of this type of interviewing is to obtain 'rich data' or 'thick descriptions' which are focused and detailed, fully revealing participants' views, feelings, intentions and actions, as well as the context and structures of their lives (Charmaz, 2006: 14), in this case, the way in which leaders cope during an economic downturn. Field notes were made during the interviews to record observations. According to Schurink (2004:11), field notes are 'written accounts of what researchers hear, see, experience, and think in the course of collecting and reflecting on the data in qualitative research studies'. This, together with interview transcripts, formed part of the data. As an important part of the research process, field notes proved invaluable during data analysis. Roughly two to three hours were spent writing field notes after each interview, including both descriptive and reflective notes, with sections on the research setting, the responses of the interviewee, and personal reflections on the interview.

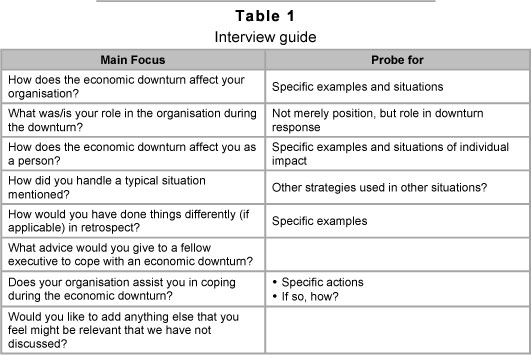

Mason (2002:231) claims that it is not possible to conduct completely structure-free interviews, arguing that as a minimum the agendas and assumptions of both the interviewer and interviewee will impose a framework for meaningful interaction. Charmaz (2006:26) holds a similar view, suggesting that researchers devise a few broad, open-ended questions in the form of an interview guide and then use their interview questions to invite detailed discussions on the topic. Table 1 provides the interview guide used in this study.

Data collection for this study was carried out during November and December 2009, a period that was, at that stage, viewed as part of the downturn. Although the mining industry (in terms of sales) started to recover, showing a positive trend, the total sales volume remained low during this period (refer to Figure 2).

3.3 Data analysis

Two types of coding were used in this study:

- Initial coding: Initial coding adheres closely to the data and does not apply pre-existing categories to it. Coding can be done per word, line or incident.

- Focused coding: This method of coding requires using the most significant and/or frequent earlier codes to sift through large amounts of data. This is done to assist the researcher in synthesizing and explaining larger segments of data (Charmaz, 2006: 58-60).

Initial coding was refined to include both micro-analysis and open coding. Micro-analysis is the careful, often minute, examination and interpretation of data (Strauss & Corbin, 1998:58), similar to the word-by-word coding described by Charmaz (2006:50). Open coding refers to uncovering, naming and developing concepts that open up the data (Strauss & Corbin, 1998:102). These two coding actions were not done separately: micro analysis was used in naming concepts in open coding. Figure 4 provides an example of open coding using ATLAS.ti employed in this study.

Secondly, focused coding was refined to two distinct 'steps' of increased focus. The first was reassembling data from open coding. This was followed by the integration and refining of categories into core categories. Table 2 illustrates how core categories were refined from categories (based on open coding).

4 Findings and discussion

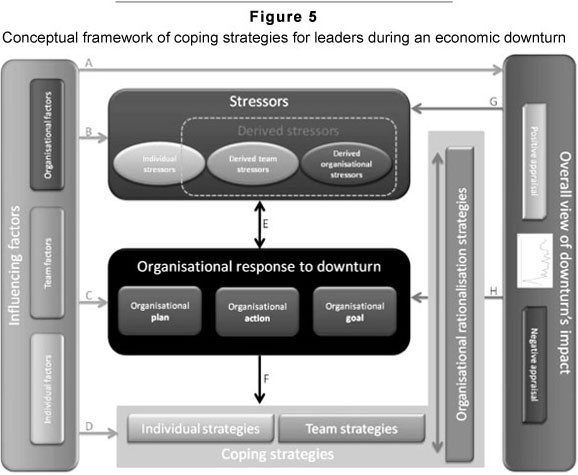

Based on various rounds of data analysis in the form of open and focused coding, a conceptual framework of coping strategies for leaders during an economic downturn was developed, as shown in Figure 5.

4.1 Influencing factors

Several factors could create a particular predisposition towards how organisational leaders cope during an economic downturn. Firstly, there are individual factors, such as being optimistic and confident, thriving on the challenge of the economic downturn and focusing on the future. In addition, the individual's experience, both general and specific, in dealing with an economic downturn and the extent to which the individual depends on (or in this case does not depend on) the organisation for identity also played a role in how leaders managed during the economic downturn.

Secondly, team factors influence how leaders cope during an economic downturn. Team factors such as the maturity of the team and inter-team influence may play a role. For example, when the core team (referring to the executive team) within which the leaders operated during the downturn was mature, the leaders tended to draw on support from the team. When the team was less mature, the leader drew more on individual coping strategies. The dynamics within the core team (termed inter-team influencing) may influence both the mood within the team and the overall appraisal of the downturn (positive or negative). In addition, the extent to which leaders influence other team members, combined with the team's maturity, could determine the extent to which leaders use team coping strategies as opposed to individual coping strategies.

Thirdly, organisational factors such as the organisational culture and the organisational level on which the leader operates create a predisposition towards how organisational leaders cope during an economic downturn.

When it comes to the organisational level, although all the respondents in this case were members of a mine or mining group's South African executive committee, they were technically at different levels of the organisation. In the case of a South African mining organisation, the executive committee members are the ultimate authority in the organisation. They are responsible to the shareholders and are on a higher organisational level than that of their counterparts in international mining organisations. South African executive committee members in the international organisations report to the mining organisation's international executive committee. The latter are on a relatively lower level of their organisation, tending to focus more on individual stressors and less on derived stressors than do their counterparts, South African executive members of a South African mining organisation.

Organisational culture also played a role in this case. For example, one organisation did not retrench any employees, based on its strong organisational culture of 'looking after each other'. Not only could organisational culture affect the organisational response to the downturn, but it could also influence the proportion of the individual, team and organisational rationalisation coping strategies that leaders use.

Individual, team and organisational factors, as shown in the conceptual framework, may therefore influence:

- the overall way in which the effect of the downturn on the organisation is viewed (for example, an individual factor such as thriving on the challenge or a team factor such as inter-team influencing, indicated by Arrow A in the conceptual framework):

- which stressors feature more prominently (for example, individual stressors and derived stressors influenced by organisational level, Arrow B);

- the organisation's response to the downturn (for example, affected by organisational culture, Arrow C); and

- the proportion of individual, team and organisational rationalisation coping strategies leaders used (for example, organisational culture, or team maturity, where more individual strategies are likely to be used if the team is less mature or the culture is less supportive, Arrow D).

This, however, is not to suggest that all leaders experience the same specific influencing factors indicated here, but merely that individual, team and organisational factors may play a role in how leaders cope during an economic downturn.

4.2 Overall view of the impact of the economic downturn

The overall view of the impact of the downturn refers to how the leaders view the economic downturn and its effect on the organisation. Leaders saw the effect on the organisation as negative, noting effects such as the loss of contracts, the negative impact on cash flow, a reduced ability to sustain capital projects, increased cost and decreased access to working capital. This list of negative impacts is not exhaustive, but reflects the views of the respondents.

However, leaders also saw the effect of the downturn on the organisation positively, perceiving it, for example, as an opportunity for revisiting strategy and structure, gaining access to an increasing pool of human resources, optimising procurement and potentially engaging in discounted acquisitions.

Assessing the effect of the economic downturn on the organisation as positive or negative should not be seen as mutually exclusive. Although leaders were aware of the negative effects, they also highlighted the positive effects of the downturn on the organisation. It is important to note that this refers to how the leaders saw the overall effect of the downturn on the organisation, and not on them as individuals. However, this overall assessment or view of the effects of the downturn on the organisation had an impact on how the organisation responded to the downturn. This referred, for example, to whether the organisation should retrench or not, hire from the extended resource pool and so forth (Arrow H) and also to which stressors (individual, team or organisational, Arrow G) feature more prominently for each individual.

4.3 Stressors

Stressors refer to aspects that contribute to the stress experienced by individuals during an economic downturn. Firstly, individual stressors are the specific aspects on an individual level that contribute to the leader's stress. Individual level stressors refer, for example, to doubting job security and, closely related, to worrying about financial security, aspects related specifically to the individual leader.

Secondly, leaders felt derived stressors which had an impact on a team. At the organisational level these were felt more acutely than the individual stressors. Although the stressors (individual and derived) all refer to individual stress, individual stressors did not seem to be the greatest contributors to the individual leaders' stress during an economic downturn, but rather stressors deriving from the distress of others. Derived team stressors created stress experienced by individuals, not on account of themselves, but rather on account of the responsibility they felt for the team. Leaders felt pressured to direct the team and the organisation. Leaders often 'pulled' trusted colleagues from their past companies into new positions which meant they had a trusted team, but it also created or at least amplified the responsibility that the respondents felt for their team members during the downturn, contributing to their stress.

Derived organisational stressors include pressure from the company or the shareholders and their expectations of the leader, feeling responsible or to blame for what happens to the organisation and the individuals working there, and experiencing a dichotomy between values (personal and organisational values) and individual actions. A specific derived organisational stressor is evident in the fact that the respondents likened their individual experience and emotions to those of an executioner, an officer in a death camp during the Holocaust or a participant in a war. These feelings are closely related to the stress of feeling responsible or to blame for what happens to the organisation and the people working there, but it also expresses a deeper sense of emotional stress experienced by the individual leaders: likening their influence on the organisation and its people to that of someone controlling life and death. Once again, the leaders did not refer to it as an individual stressor, but rather as individual stress (in other words, distress experienced by the person) derived from others' distress for which the leader perceives himself to be (at least partially) responsible.

It was interesting to note that the derived stressors seemed to be more important and stressful to the leaders than the individual stressors influencing only themselves. This is also what they largely attempted to cope with during the downturn. Note that, although all stressors (individual and derived team and organisational stressors) are individually experienced stressors, they stem from different sources, that is, the individual, team and organisational levels.

4.4 Organisational response to economic downturn

The organisational response to the downturn consists of actions taken to achieve a specific goal, based on a plan on how to deal with the organisational downturn. Firstly, the short- and long-term organisational goals are considered. In the short term, organisations focus on surviving the critical, immediate actions that will ensure that the organisation is able to withstand the downturn. In the long term, the organisation needs to position itself to be ready for the upswing; it needs to have a vision and to ensure that the people in the organisation are prepared to be in business in the long run.

Secondly, an organisational plan is derived from how to achieve these short- and long-term goals. This plan of action should be based on facts: the state of the markets and industries, the core of the problem and so forth, focusing on specific problems in the organisation as opposed to the generic threat of the economic downturn.

Thirdly, the plan should be implemented by taking specific organisational actions, whether it is to reduce capital spending, reduce costs (for example, by means of retrenchment) or other, more strategic actions (such as attempt-ting to control the market). Organisational action in response to the economic downturn is often defined in terms of retrenchment, often ex negativo. Where organisations carried out retrenchments, respondents focused mostly on their coping with this organisational action. If organisations did not retrench, respondents were proud of this organisational 'non-action', but often also focused on coping with the threat of retrenchment in the organisation.

The organisational response to the downturn influences the choice of which coping strategies are used. For example, if retrenchment is an organisational action during the downturn, the leader in the organisation concerned may experience stressors (Arrow E) that differ from those experienced by a leader in an organisation that does not retrench. This therefore influences the coping strategies that the leader might use in order to cope (Arrow F), as well as subsequent organisational responses (Arrow E).

4.5 Coping strategies

Coping strategies are methods used for coping with stressors, in this case, during an economic downturn. Different coping strategies that leaders might use in combination were identified. Firstly, individual coping strategies refer to strategies that fall within the individual domain or level. This includes religion, the balance between work and life, spousal support in the form of providing a sounding board, or when, for example, a spouse takes over decision-making responsibilities at home, as well as emotional separation in an attempt to depersonalise actions.

Secondly, team coping strategies are methods whereby a person draws on the core team and/or the team reporting to him to cope better with stressors. This includes, first of all, the mere fact of having a core team and not facing all the challenges alone. Trusting this core team is an important element in team coping, particularly because being part of a core team allows pressure to be shared. In addition, leaders also indicated the importance of trusting the team reporting to them, which enabled these leaders to focus on their own actions during the downturn.

Lastly, organisational rationalisation strategies refer to strategies that leaders use to cope with the stressors during the economic downturn by attempting to rationalise the actions brought about by the organisation's response to the economic downturn. This may take several forms: for example, feeling compelled to act in the interest of organisational survival during the downturn, having to convince themselves that they are doing the right thing, seeking guidance, and believing in the organisational plan of action and then rationalising their actions against this plan.

The specific coping strategies mentioned here are based on the experiences of the respondents in this study and the list may therefore not be exhaustive. However, the findings suggest that, in addition to individual coping strategies, leaders may also use team and organisational rationalisation strategies in order to cope with the stressors during an economic downturn. In addition, a combination of coping strategies seemed to be used to cope with a combination of individual and/or derived team and organisational stressors and one should not incorrectly presume that, for example, individual coping strategies are used merely for coping with individual stressors.

5 Conclusion and recommendations

The main objective of this study was to develop a guiding framework for use by South African business leaders to help them cope with adverse conditions like an economic downturn. This objective was reached by developing a conceptual framework of coping strategies for leaders during an economic downturn, as outlined in Section 4 of this paper.

We believe that this study contributes methodologically to the field of coping research by demonstrating that alternative methodologies (in this case, qualitative research) using narrative approaches (interviews) can uncover ways of coping that are not included in traditional coping inventories. This methodology also allowed for a more in-depth understanding of the phenomenon being studied in the particular context of an economic downturn, in answer to Somerfield and McCrae (2000:624), who appeal to researchers to focus on coping responses to specific situations within a specific context rather than general coping strategies.

In addition, the study contributes to coping theory at various levels (the individual, team and organisational levels), thus moving beyond the dominant individualist perspective of coping which has recently received increasing criticism (Muhonen & Torkelson, 2008:451).

Lastly, this study contributes at a practical level, providing leaders and organisations with a better understanding of how leaders cope in an organisational context during adverse condi- tions like an economic downturn. This understanding facilitates several recommendations:

- Organisations, specifically managers and leaders, should be vigilant about maintaining a continuous proactive environmental analysis strategy whereby potential opportunities and threats in the environment are constantly identified and monitored (Lynch, 2000:105). This will allow individuals within the organisation to prepare and act timeously in the event of an economic downturn or any other problem. More importantly, leaders should remain open to information gained from environmental analysis.

- Leaders should proactively attempt to develop positive attributes within the organisation, and specifically within themselves. Luthans, Youssef and Avolio (2007: 213) propose that what they call positive psychological capital, which includes hope, optimism, self-efficacy and resilience, is open to development. These positive psychological capacities correspond to several individual influencing factors that create a predisposition in respect of how organisational leaders cope during an economic downturn, including being optimistic (optimism), being confident in their own capabilities (self-efficacy) and focusing on the future (hope, resilience). In light of this, organisations can develop these capacities to assist them and their leaders in coping with adverse conditions. For example, hope is said to be developed by means of goal-setting, participation and contingency planning for alternative pathways to attain goals (Snyder, Irving & Anderson, 1991, cited in Snyder, Rand & Sigmon, 2005: 258).

- Organisations should embrace the concept of workplace spirituality. According to Duchon and Plowman (2005:809), a workplace can be considered spiritual when it 'recognizes that employees have an inner life that nourishes and is nourished by meaningful work that takes place in the context of community'. The present study has shown that belief systems, an important element of workplace spirituality, according to Hicks (2002:384), can play an important role in coping during an economic downturn. Giacalone and Jurkiewicz (2003: 85) found that the degree of individual spirituality influences whether an individual perceives a questionable business practice as ethical or unethical, tying in with what we termed the "value dichotomy" as a derived organisational stressor and the belief that one is "doing the right thing" as an organisational rationalisation coping strategy used by leaders.

- Organisations and organisational leaders should carefully consider the selection, composition and team development of their executive teams owing to the important role that team coping strategies have been shown to play in coping during an economic downturn. In addition, the culture of the organisation and the team should support teamwork and trust. Hence, active efforts should be put into place to develop this.

A limitation of this study is that all the respondents were white males, so findings could not be generalised. The timing of the interviews and data collection, during November and December 2009, could have potential bias towards the recall of respondents' thoughts, feelings and behaviour related to coping during the 'heat' of the downturn.

Several opportunities for future research have been identified:

- The conceptual framework of coping strategies for leaders during an economic downturn can be tested in other industries for its relevance. Comparative results may yield further insight into the model and may allow for its expansion.

- The conceptual framework of coping strategies for leaders during an economic downturn can be elevated to a model in theory, focusing more on explaining concepts and their relationship to each other.

- The conceptual framework can be researched at various levels in the organisation, comparing the coping strategies of leaders with those of employees in lower organisational levels.

References

BABBIE, E. 2007. The practice of social research. (11th ed.) Balmont, CA: Thompson Wadsworth. [ Links ]

CHARMAZ, K. 2006. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage. [ Links ]

CONGER, J.A. 1998. Qualitative research as the cornerstone methodology for understanding leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 9(1):107-121. [ Links ]

DUCHON, D. & PLOWMAN, D.A. 2005. Nurturing the spirit at work: impact on work unit performance. Leadership Quarterly, 16(5):807-833. [ Links ]

EVERED, R. & LOUIS, M. 1981. Alternative perspectives in organizational sciences: 'Inquiry from the inside' and 'Inquiry from the outside'. Academy of Management Review, 6(3):385-395. [ Links ]

FOLKMAN, S. & MOSKOWITZ, J.T. 2004. Coping: pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1):745-774. [ Links ]

GIACALONE, C.L. & JURKIEWICZ, C. 2003. Right from wrong: the influence of spirituality on perceptions of unethical business practices. Journal of Business Ethics, 46(1):85-97. [ Links ]

HENNING, E. 2004. Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

HICKS, D.A. 2002. Spiritual and religious diversity in the workplace: implications for leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 13(4):379-396. [ Links ]

HOBFOLL, S.E., SCHWARZER, R. & CHON, K.K. 1998. Disentangling the stress labyrinth: interpreting the meaning of the term stress as it is studied in health context. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 11(3):181-212. [ Links ]

KAHN, B. 2009. South Africa's policy may offset the financial downturn. Development Outreach - World Bank Institute. December 2009. Available at: http://wbi.worldbank.org/wbi/devoutreach/article/260/south-africa%E2%80%99s-policy-responses-effects-global-financial-crisis [ [ Links ]accessed 2010-03-07].

LAZARUS, R.S. 2000. Toward better research on stress and coping. American Psychologist, 55(6):665-673. [ Links ]

LAZARUS, R. & FOLKMAN, S. 1984. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

LUTHANS, F., YOUSSEF, C.M. & AVOLIO, B.J. 2007. Psychological capital: developing the human competitive edge. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

LYNCH, R. 2000. Corporate strategy. (2nd ed.) New York: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

MARAIS, H. 2010. The impact of the global recession on South Africa. Available at: http://www.amandlapublishers.co.za/home-menu-item/156-the-impact-of-the-global-recession-on-south-africa [ [ Links ]accessed 2010-04-03].

MASON, J. 2002. Qualitative interviewing: Asking, listening and interpreting. In T. May (ed.) Qualitative research in action. (pp.225-241) London: Sage. [ Links ]

MUHONEN, T. & TORKELSON, E. 2008. Collective and individualistic coping with stress at work. Psychological Reports, 103(2):450-458. [ Links ]

NAIMAN, S. 2009. Generating positive energy in the workplace during hard times. Employment Relations Today, 36(1):49-55. [ Links ]

SCHURINK, W. 2004. Lecture 10: Data Analysis. University of Johannesburg, 27-28 February. Johannesburg. [ Links ]

SHABANGU, S. 2009. Department of Minerals and Energy budget vote speech by Ms Susan Shubangu, Minister of Mineral Resources on 23 June. Available at: http://www.pmg.org.za/briefing/20090623-mining-ministers-budget-speech [ [ Links ]accessed 2009-02-07].

SHAN, S. & CORLEY, K. 2006. Building better theory by bridging the quantitative-qualitative divide. Journal of Management Studies, 43(8):1821-1835. [ Links ]

SILVERMAN, D. 2005. Doing qualitative research. (2nd ed.) London: Sage. [ Links ]

SNYDER, C., RAND, K. & SIGMON, D. 2005. Hope Theory: a member of the Positive Psychology family. In Snyder, C.R. & López, S.J. (eds.) Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp.257-276). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

SOMERFIELD, M.R. & MCCRAE, R.R. 2000. Stress and coping research: methodological challenges, theoretical advances, and clinical applications. American Psychologist, 55(6):620-625. [ Links ]

SOUTHERN AFRICAN RESOURCE WATCH. 2009. Impact of the global financial crisis on mining in Southern Africa. Johannesburg: Southern African Resource Watch. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA. 2009. Mining: production and sales. Statistical Release P2041. May. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA. 2010a. Gross domestic product: Fact Sheet 1, 2009. Statistical Release P0441. 23 February. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA. 2010b. Gross domestic product -fourth quarter: 2009. Statistical Release P0441. 23 February. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA. 2010c. Mining: production and sales (preliminary). Statistical Release P2041. February. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. [ Links ]

STERN, P. 2007. On solid ground: essential properties for growing grounded theory. In Bryant, A. & Charmaz, K. (eds.) The Sage handbook of grounded theory (pp.114-126). Los Angeles: Sage. [ Links ]

STRAUSS, A. & CORBIN, J. 1998. Basics of qualitative research. 2nd ed. London: Sage. [ Links ]

URQUHART, C. 2007. The evolving nature of grounded theory method: the case of the information systems discipline. In Bryant, A. & Charmaz, K. (eds.) The Sage handbook of grounded theory (pp. 339-362). Los Angeles: Sage. [ Links ]

Accepted: September 2012