Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versión On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.15 no.4 Pretoria ene. 2012

ARTICLES

Does personality matter for small business success?

Shelley M Farrington

Department of Business Management, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

ABSTRACT

Personality traits influence occupational choice and are valid predictors of managerial success. The primary objective of this study was to investigate whether a relationship exists between possessing certain personality traits and small business success. The personality dimensions of the five-factor model of personality, Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Openness to experience, Agreeableness and Neuroticism were the focus of this study.

Convenience sampling was employed and 383 usable questionnaires were returned. The validity and reliability of the measuring instrument was assessed. Multiple regression analysis was undertaken to establish relationships between the independent variable (the five dimensions of personality) and the dependent variable, Business success.

The findings of this study show that individuals who have high levels of the personality traits Extraversion, Conscientiousness and Openness to experience are more likely to have successful small businesses. Openness to experience is of specific importance as it demonstrates the strongest influence, and is the only trait that has a positive influence on both the financial and growth performance of the business. As such, insights are provided into the personality profile most suited to successful small-business ownership.

Key words: entrepreneurship, small business, personality, five-factor model of personality

JEL: L260

1 Introduction

Personality dispositions are associated with happiness, physical and psychological health, and the quality of relationships, as well as occupational choice, job satisfaction and performance (Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006; Judge, Higgins, Thorsen & Barrick, 1999). The relationship between personality and performance is well supported by several meta-analyses (Bergner, Neubauer & Kreuzthaler, 2010; Barrick, Mount & Judge, 2001), and personality traits are agreed to be valid predictors of managerial performance (Bergner et al., 2010). For example, Nadkarni and Herrmann (2010:1050) contend that the personality of a business leader influences the strategic decision processes and strategic actions of a firm, ultimately having implications for the firm's performance. Finkelstein and Hambrick (1996) conclude that the personality of a business leader has consequences for a firm. According to McCrae and Costa (1980), personality traits influence a person's tendency to act, and different tendencies can enable or hinder a business owner's behaviour. In their study among project managers, Davir, Sadeh and Malach-Pines (2006) have found that when the personality type of the project manager matches the project type, more successful projects result. Similarly, Douglas (n.d.) suggests that personality has a great deal to do with being a successful entrepreneur.

According to Burger (2008:4), personality is the consistent behaviour patterns and intra-personal processes that originate from within an individual, whereas Haslam (2007:4) describes personality as characteristics that give a person their individuality. It is widely accepted that five broadly defined dimensions of personality exist. These five dimensions serve as a suitable method for classifying personality attributes and make up what is known as the five-factor model of personality (Bergner et al., 2010; Llewellyn & Wilson, 2003; Costa & McCrae, 1992; Barrick & Mount, 1991). The five-factor model of personality, often termed the 'big five' (Costa & McCrae, 1992), can be used to describe the most salient aspect of personality (Judge, Heller & Mount, 2002) and consists of five broad dimensions of personality, namely extraversion, conscientiousness, openness to experience, agreeableness and neuroticism, (Bergner et al., 2010; Cooper & Pervin, 1998). These dimensions and their measures have proved to be a reliable and valid measure of personality and are among the most robust in existence (Hetland, Mjeldheim & Johnsen, 2008; Barrick & Mount 1991). The dimensions of the five-factor model are widely used in the personality and prediction literature (Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006), and have been researched in many areas of industrial-organisational psychology, most often with regard to job performance (Barrick & Mount, 1991).

It is possible that many small-business owners are not suited, based on their personality disposition, to the occupation of 'self-employment'. A high failure rate exists among small businesses in South Africa (Small business development in South Africa, 2009) and a lack of suitability could be an explanation for the low levels of business performance and ultimate business failure. Over the last two decades personality has increasingly been investigated and used as a means of personnel selection and human resource development (Bergner et al., 2010; Barrick & Mount, 1991). The question arises why personality cannot be used to 'select' or identify individuals who would be suitable for small-business ownership. This study attempts to establish whether a specific personality disposition can be associated with successful 'self-employment' and ultimately a successful business. More specifically, this study investigates the influence of a small-business owner's personality on the success of his/her small business.

Previous efforts to investigate the relationship between personality traits and entrepreneurship have centred on the use of narrow traits such as risk-taking, locus of control and need for achievement (Llewellyn & Wilson, 2003). These studies have confirmed that further research is needed to evaluate the role of personality in relation to entrepreneurship (Llewellyn & Wilson, 2003). Similarly, calls have recently arisen to make use of comprehensive and valid psychological frameworks to investigate the relationships between a business leader's personality attributes and firm performance (Hiller & Hambrick, 2005; Cannella & Monroe, 1997). As far as can be established, no studies using the five-factor model of personality exist attempting to investigate whether the personality dispositions of small-business owners have an influence on the success of their business.

Against this background, the primary objective of this study is to investigate whether a relationship exists between possessing certain personality traits and small business success. By identifying the personality traits associated with business success, proactive steps can be made to identify individuals who are more likely to be successful at self-employment. In an effort to guide future entrepreneurs, the ultimate goal is to identify the trait profile most common to successful small-business owners.

For the purpose of this study, a small business is defined as one that does not employ more than 50 full-time employees. In addition, the business should have been in operation for at least one year and the owner must be actively involved in the business. According to Judge, Bono, Ilies and Gehardt (2002), the five-factor model of personality is a framework that provides a valid, robust and comprehensive way of representing fundamental personality differences between individuals. In the present study, personality is represented by the personality dimensions of the five-factor model, namely Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Openness to experience, Agreeableness and Neuroticism.

2 Literature overview

2.1 Personality and personality traits

Defining 'personality' is a complex task (Gordon, 2002) and several descriptions are evident in the literature. 'Personality' refers to the qualities that form a person's character (Waite & Hawker, 2009:681), or the characteristic patterns of thought, feelings and behaviours that make a person unique (Cherry, n.d). 'Personality traits' are more specific constructs that explain consistencies in the way people behave, and help to explain why different people react differently to the same situation (Llewellyn & Wilson, 2003). Personality traits determine a person's words, deeds and role in life (Cooper, 1998), and as such, an individual's actions and thinking are derived from the personality traits they possess (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Personality traits differ in type and degree for everybody (Costa & McCrae, 1992).

2.2 The five-factor model of personality (The big five personality dimensions)

Several researchers (Norman 1963; Fiske 1949, Cattell 1946) have contributed to the development of a framework consisting of five personality factors. This five-factor model demonstrates that personality consists of five relatively independent dimensions which provide a useful means for studying individual differences (Thal & Bedingfield, 2010; Costa & McCrae, 1992; Barrick & Mount, 1991). It categorises the many personality traits into a more manageable number and has thus made personality a more easily accessible topic (Bergner et al., 2010). Furthermore, the model provides a framework for understanding how traits combine to form the way in which people think, feel and behave in the world (Foulkrod, Field & Brown, 2009:422) and is therefore suitable for measuring individual personality traits (Chen & Lai, 2010). The five broad factors or personal trait dimension, Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Openness to experience, Agreeableness and Neuroticism, have been identified through empirical research (Goldberg, 1993) and have consistently been replicated as dimensions of enduring personality characteristics (Foulkrod et al., 2009:422). Although opinion is not yet unanimous, there is increasing agreement among researchers that the traits identified in the five-factor model of personality capture the most important aspects of personality (Nadkarni & Herrmann, 2010; Judge et al., 2002; McCrae & Costa, 1997).

The big five are five broad domains or dimensions of personality which have been scientifically accepted as defining human personality at the highest level of organisation (Goldberg, 1993). Barrick, Mount and Gupta (2003:46) assert that the five-factor model describes the basic dimensions of personality at a global level, and that specific personality traits are likely to connect with at least one of the five dimensions. These five factors provide a rich conceptual framework for integrating all research findings and theory in personality psychology (Costa & McCrae, 1992). The five factors are broad personality constructs, with each capturing a unique set of psychological traits (Nadkarni & Herrmann, 2010:1052), several of which will be identified in the paragraphs below.

The trait of Extraversion represents sociability and expressiveness (Nadkarni & Herrmann, 2010; Judge et al., 2002) and is frequently associated with individuals being sociable, assertive, talkative and active (Llewellyn & Wilson, 2003; Costa & McCrae, 1992; Barrick & Mount, 1991). Individuals high in extraversion are described as outgoing, gregarious, optimistic and upbeat (Weiten 2010; Barrick et al., 2003), as well as energetic, enthusiastic and adventurous (John, 1990). Costa and McCrae (1992) describe extraverted people as frank and cheerful as well as being inclined to experience positive emotions. Typically, people high in extraversion seek out the company of others and enjoy environmental stimulations, whereas those low in extraversion prefer to spend time alone and are more reserved, quiet and independent (Foulkrod et al., 2009:422). Extraverted leaders tend to take the initiative in social settings, to introduce people to each other and to be socially engaging by being humorous, introducing topics of discussion and stimulating social interactions (House & Howell, 1992).

Conscientiousness, also sometimes referred to as 'a conscience', reflects dependability, being careful, thorough, organised and responsible. In addition, people who are conscientious are hardworking and achievement-orientated, and persevere in their endeavours (Nadkarni & Herrmann, 2010; Judge et al., 2002; McCrae & Costa, 1997; Barrick & Mount, 1991). John (1990) describes conscientiousness as relating to issues of control and constraint, which includes traits such as efficiency and deliberation. Costa and McCrae (1992) report behaviours of highly conscientious individuals as fussy, tidy, scrupulous, strong-willed and punctual, whereas Foulkrod et al. (2009) include aspects such as the ability to organise, goal-directed behaviour, holding impulsive urges in check, and working diligently. According to Barrick et al. (2001), individuals who score high on conscientiousness are orderly and hardworking, and have a tendency to be self-disciplined, act dutifully, aim for achievement, and plan ahead rather than act spontaneously. Furthermore, conscientious individuals have a strong need to reduce uncertainty and to receive specific feedback on their performance (Judge et al., 2002).

Openness to experience, also sometimes referred to as 'intellect' (Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006; Barrick & Mount, 1991) is associated with traits such as originality and open-mindedness as well as being artistic, insightful, imaginative and intelligent (Barrick et al., 2003; John, 1990). Weiten (2010) as well as Barrick and Mount (1991) also include traits such as being cultured, curious and flexible and having an unconventional attitude, whereas Costa and McCrae (1992) refer to independence and an inquiring intellect when describing this personality dimension. Being perceptive and thoughtful are also traits associated with openness to experience (Nadkarni & Herrmann, 2010). Openness to experience determines whether one is likely to seek out new ideas and think creatively or whether one is more practical-minded, efficient and conservative in outlook (Douglas, n.d). Costa and McCrae (1992) are of the opinion that individuals who score high on openness to experience show social poise and are polished, while McCrae (1990) contends that these individuals are associated with a high tolerance of ambiguity and an affinity for unconventional ideas. 'Open' individuals have a strong need for change and are highly capable of understanding and adapting to the perspectives of others (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Leaders who are open to new experiences actively seek out excitement and risks (Judge et al. , 2002), whereas individuals who score low on openness to experience tend to have a conservative outlook and prefer the familiar to the unusual (McCrae & Costa, 1980).

According to Foulkrod et al. (2009:423), Agreeableness describes a cluster of personality traits such as altruism, nurturance, or caring at the high end of the spectrum, and hostility, indifference and egocentrism at the lower end. Agreeableness represents the tendency to be altruistic (empathetic, kind, cooperative, trusting and gentle) and compliant (modest, having a values affiliation and avoiding conflict) (Bono & Judge, 2004). Agreeableness has also been labelled as likeability or friendliness, and includes traits such as being courteous, considerate, flexible, trusting, good-natured, forgiving, soft-hearted and tolerant (Barrick et al., 2003; Barnck & Mount, 1991), affectionate, generous and sympathetic John (1990), as well as modest and straightforward (Weiten, 2010). Highly agreeable people are easy to get on with and will probably be widely liked (Llewellyn & Wilson, 2003). They are friendly and eager to help others and have a tendency to be compassionate rather than suspicious and antagonistic towards others (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Furthermore, behaviour associated with highly agreeable individuals includes being good-natured, mild, emotionally mature, self-sufficient and attentive to others (Costa & McCrae, 1992).

Neuroticism refers to the tendency of an individual to experience unpleasant emotions easily. Common traits displayed by neurotic individuals include anxiety, depression, anger, embarrassment, worry and insecurity (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Barrick & Mount, 1991). Neurotic individuals are prone to mood swings, are emotionally unstable, highly excitable (Llewellyn & Wilson, 2003; Costa & McCrae, 1992) and self-conscious (Weiten, 2010). The reverse of neuroticism is referred to as Emotional stability (Barrick & Mount, 1991) which reflects the capacity of an individual to adjust their emotional state to the demands of the situation and being able to remain calm and balanced when faced with adversities and stressful situations (Nadkarni & Herrmann, 2010; Foulkrod et al., 2009; McCrae & Costa, 1997). Individuals who have low emotional stability are moody, melancholy and apprehensive (Raab, Stedham & Neuner, 2005), as well as hostile, envious and impulsive (Foulkrod et al., 2009; Costa & McCrae, 1992). According to Barrick et al. (2003:51), individuals who are low in emotional stability are prone to stress, suggesting that these people would prefer stress-free jobs.

2.3 Entrepreneurial personality

The entrepreneurship literature identifies numerous attributes (traits, characteristics and skills) associated with entrepreneurial behaviour and entrepreneurial success (Deakins & Freel, 2009; Ramana, Aryasri & Nagayya, 2008; Mahadea, 2001). Hornaday (1982) identifies as many as 42 different characteristics common to entrepreneurs, however, those most commonly cited are the need to achieve, ability to take risks, tolerance for ambiguity, good locus of control, creativity and innovation (Chen & Lai, 2010; Deakins & Freel, 2009; Venter, Urban & Rwigema, 2008).

According to Soetanto, Pribadi and Widya-dana (2010), an abundance of literature exists attempting to define the attributes that distinguish entrepreneurs from others (Raab et al., 2005; Cromie, 2000). As such various personality attributes are associated with successful entrepreneurs and small-business owners. According to Barrick et al. (2003), the various attributes or personality traits associated with successful entrepreneurs are likely to be associated with at least one of the five broad dimensions of the five-factor model. As an example, Table 1 attempts to categorise several well-known entrepreneurial traits into the dimensions of the five-factor model.

3 Hypotheses development

Research relating to the relationship between personality and job performance has largely been framed by the five-factor model of personality (Bergner et al., 2010; Barrick & Mount 1991). Meta-analytic research (Rothstein & Goffin, 2006; Barnck & Mount, 1991; Tett, Jackson & Rothstein, 1991) has confirmed the use of the five-factor model to predict performance in the workplace. Several researchers (Barrick et al., 2001; Barnck & Mount, 1991) have found strong correlations between job performance and the five-factor model of personality. According to Foulkrod et al. (2009), compelling evidence exists supporting the ability of the five-factor model of personality to predict professional achievement.

3.1 Dependent variable

Little agreement exists on an appropriate measure for small business success (Acs, Glaeser, Litan & Fleming, 2008) and previous research has mainly focused on variables for which information is easy to gather (Cooper, 1995). Although several researchers advocate growth as the most important performance measure for small businesses (Brown, 1996; Chandler & Hanks, 1993; Tsai, MacMillan & Low, 1991), others consider performance to be multidimensional in nature, adding that it is advantageous to integrate different dimensions of performance in empirical studies (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). According to Zahra (1991), financial performance and growth performance represent different aspects of performance and each reveals important performance information. Taken together, growth and financial performance provide a richer description of the actual performance of the firm than each does on its own (Zahra, 1991).

For the purpose of this study, the success or performance of the small-business owner is measured in terms of the success of his or her business, and this is measured in terms of both growth and financial indicators. Business success refers to the business being successful, profitable and financially secure, and showing growth in turnover, profits and number of employees.

3.2 Independent variables

The personality dimensions of the five-factor model, namely Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Openness to experience, Agreeableness and Neuroticism, are the independent variables to be investigated in this study. These five traits have consistently been replicated as dimensions of enduring personality characteristics (Foulkrod et al., 2009).

Barrick and Mount (1991) report that Conscientiousness appears to reflect traits which are important to the accomplishment of tasks in all jobs, and that measures associated with Conscientiousness are most likely to be valid predictors of job performance for all jobs. Barrick and Mount (1991) report Extraversion to be a valid predictor of job performance for positions in management and sales. Interacting with others is a significant part of these types of jobs. Traits such as being sociable, gregarious, talkative, assertive and active would lead to effective performance in these types of jobs. However, Extraversion would be less important in jobs such as skilled/semi-skilled and professionals (Barrick & Mount, 1991).

Barrick and Mount (1991) found no relationship between Openness to experience and job performance and concluded that this trait was not a valid predictor of job performance. Low correlations were reported between Emotional stability and job performance (Barrick & Mount, 1991). For professionals, Emotional stability produced a negative correlation, suggesting that individuals who are worrying, nervous, emotional, and high-strung are better performers in these jobs (Barrick & Mount, 1991:20). Barrick and Mount's (1991:21) results for Agreeableness suggest that this trait is not an important predictor of job performance, implying that being courteous, trusting, straightforward and soft-hearted have a smaller impact on job performance than being talkative, active and assertive.

In their later meta-analysis investigating the relationship between the personality dimensions of the five-factor model and job performance, Barrick et al. (2001) found that in addition to Conscientiousness, Emotional stability (inverse of Neuroticism) is also positively correlated with performance criteria in virtually all jobs across organisations and countries. The other dimensions, Agreeableness, Extraversion and Openness to experience also proved to be valid predictors of performance but their relationship to job performance varies depending on criteria and occupational groups. Once again Extraversion was found to be a valid predictor but only for occupations typically requiring interactions with others (e.g. managers and sales). Openness to experience and Agreeableness displayed weak relationships with overall job performance (Barrick et al., 2001).

In their study investigating the ability of personality to predict project manager success, Thal and Bedingfield (2010) found that Conscientiousness and Openness to experience are strongly correlated with perceptions of performance. A positive correlation between Conscientiousness and job performance is well supported in the literature (Salgado, 2003; Barrick & Mount, 1991). The findings of Thal and Bedingfield (2010) regarding Openness to experience, however, contradict those of Barrick et al. (2001) who found Openness to experience to have a weak relationship with job performance. Consistent with the literature, Thal and Bedingfield (2010) found that Emotional stability is a good predictor of project success. Thai and Bedingfield (2010) found little support for Extraversion and Agreeableness being able to predict success. In contrast to Thal and Bedingfield (2010), Witt, Burke, Barrick and Mount (2002) found Extraversion to be positively correlated with performance among highly conscientious workers and negatively correlated with less conscientious workers. As reported by Thal and Bedingfield (2010), Agreeableness has consistently been shown to have little influence on performance.

More recent meta-analyses (Bergner et al., 2010), show that the relationship between personality traits and performance differs to some degree among people in executive positions. According to Judge et al. (2002), Extraversion produced the highest correlations with managerial performance across different criteria and across different vocational settings. Following Extraversion, Conscientiousness displayed the strongest and most stable correlations across managerial performance criteria and across management settings. The correlations of Neuroticism and Openness to experience with managerial performance showed that these two personality factors were of equal importance, whereas Agreeableness appeared to be the least relevant of the big five traits. Similarly, Bergner et al. (2010) report Extraversion and Conscientiousness as being the most consistent correlates with success across different criteria. Bergner et al. (2010) conclude that within a group, individuals who are extraverted and conscientious as well as emotionally stable and open to experience will emerge as leaders.

In their study investigating CEO personality and firm performance, Nadkarni and Herrmann (2010) found that Extraversion, Emotional stability and Openness to experience enhanced firm performance by fostering strategic flexibility, whereas Conscientiousness undermined firm performance by inhibiting strategic flexibility. The results of Nadkarni and Herrmann (2010) for Emotional stability, Extraversion and Openness to experience are consistent with published psychology and leadership research (Bono & Judge, 2004; Judge et al., 2002). However, their results for Conscientiousness and Agreeableness differ somewhat from those of existing studies. Their results indicate that Conscientiousness undermines firm performance by inhibiting strategic flexibility, whereas a medium level of Agreeableness maximises strategic flexibility and consequently firm performance. Nadkarni and Herrmann (2010) conclude that very high levels of Conscientiousness may result in inertia and adverse performance, whereas very low levels of Conscientiousness may create instability and uncertainty for firms, and as a result firm performance may be maximised at medium levels of Conscientiousness.

Given the contradictory findings elaborated on in the paragraphs above, it was decided to subject the following hypotheses to empirical testing:

H1 There is a positive relationship between possessing the trait Extraversion and the Business success experienced by a small-business owner.

H2 There is a positive relationship between possessing the trait Conscientiousness and the Business success experienced by a small-business owner.

H3 There is a positive relationship between possessing the trait Openness to experience and the Business success experienced by a small-business owner.

H4 There is a positive relationship between possessing the trait Agreeableness and the Business success experienced by a small-business owner.

H5 There is a negative relationship between possessing the trait Neuroticism and the Business success experienced by a small-business owner.

4 Research methodology

4.1 Measuring instrument

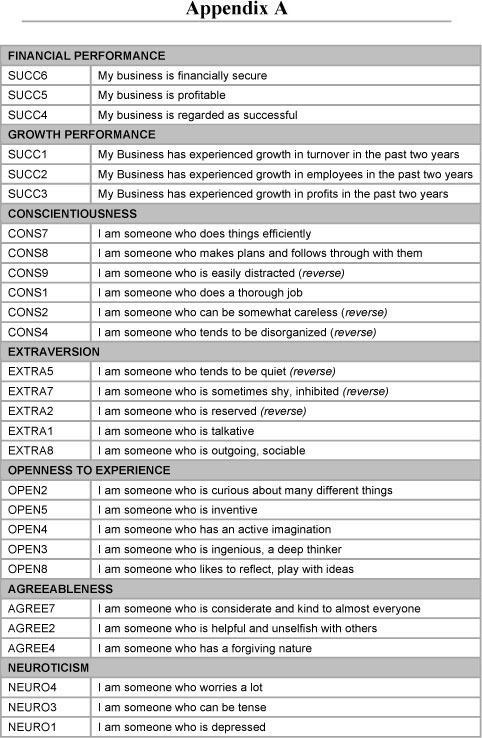

This study makes use of an existing measuring instrument to collect the necessary data, namely the 'big five inventory'' (BFI). The BFI is a self-report inventory designed to measure the big five dimensions of the five-factor model of personality, and consists of 44 statements (Srivastava, 2010). The questionnaire also contains six items to measure the dependent variable Business success. These six items have been used in previous studies (Eybers, 2010; Farrington, 2009; Cowie, 2007) and relate to perceptions of success, profitability and financial security as well as increasing turnover, profits and number of employees.

The measuring instrument consisted of a covering letter and two sections. The cover letter stipulated the objective of the study, detailed the criteria for participation, and provided assurances of confidentiality. Section 1 of the questionnaire requested general demographic information from respondents and Section 2 contained 44 statements describing various aspects of a person's nature. Several of these items were negatively phrased and were reverse-scored for the statistical analysis. Section 2 also contained 6 items relating to Business success. A 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree) was used, requesting respondents to indicate the extent of their agreement or disagreement with the statements posed.

4.2 Sampling and data collection

As far as can be established, no national database or list of small businesses exists in South Africa or in the Eastern Cape. Therefore, a convenience sampling technique was employed in this study. The focus of the study was on small businesses in the Eastern Cape Province. To be eligible to participate in the study, respondents had to meet specified criteria, namely, operate a business in the Eastern Cape Province, the business had to have been in operation for at least one year, did not employ more than 50 full-time employees and the owner of the business had to be actively involved in the business. During the months of March and April 2010, fieldworkers from the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University approached small-business owners in the Eastern Cape and invited them to participate in the study. The questionnaires were personally delivered to the small-business owners and collected upon completion. A total of 383 usable questionnaires were returned.

5 Empirical results

The data collected were subjected to various statistical analyses using SPSS (SPSS Inc, 2008). An exploratory factor analysis was undertaken and Cronbach-alpha coefficients (CA) were calculated to assess the discriminant validity and reliability of the measuring instrument respectively. Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarise the sample data and the hypothesised relationships were assessed by means of multiple regression analysis. Multiple regression analysis was considered appropriate for this study because it allows a researcher to predict the score of one variable (Business success) on the basis of scores reported on several other variables (five personality dimensions).

5.1 Sample description

The majority of the respondents participating in this study were males (69.7 per cent) and 28.5 per cent were females. Most (35.0 per cent) respondents were between 40 and 49 years old and 57.4 per cent were white. Of the respondents, 66.8 per cent held a tertiary qualification. Tenure referred to how long the respondent had owned the business. In this study, the majority (81.5 per cent) of respondents had owned the business for more than 3 years. The majority (75.7 per cent) of respondents employed fewer than 10 people. Industry referred to the nature of the business, or the industry in which the business operated. Most (45 per cent) respondents were in the service industry, followed by the retail and wholesale industries (21 per cent).

5.2 Discriminant validity and reliability results

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted to identify the unique factors present in the data, and to assess the discriminant validity of the measuring instrument. Principal axis factoring with an oblimin rotatin (Oblimin with Kaiser Normalisation) was specified as the extraction and rotation method. In determining the factors (constructs) to extract the percentage of variance explained and the individual factor loading were considered. Bartlett's Test of Sphericity reported a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure (KMO) of 0.791 (p<0.001) confirming that the data were factor-analysable.

Seven factors were extracted by means of the exploratory factor analysis. These seven factors explained 55.75 per cent of the variance in the data. The seven factors were identified as the theoretical dimensions of Financial performance, Growth performance, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Openness to experience, Agreeableness and Neuroticism The factor structure is presented in Table 2.

Six items were developed to measure Business success. Three of these items loaded onto one construct named Financial performance and the other three items loaded together onto a different construct, named Growth performance. Despite the items measuring the personality dimensions being sourced from the BFI self-report inventory which has been proved valid and reliable (Srivastava, 2010), several items relating to each of the personality dimensions did not load as expected. Items that did not load or which loaded onto more than one factor were eliminated from further analysis. Factor loadings of > 0.35 (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson & Tatham, 2006) were reported for all items, providing evidence of construct and discriminant validity for the measuring scales.

Based on the results of the factor analyses, the hypotheses relating to Business success were reformulated to reflect both Financial and Growth performance. These hypotheses are listed below:

H1a -1b There is a positive relationship between possessing the trait Extraversion and the Financial and Growth performance of the small business.

H2a - 2b There is a positive relationship between possessing the trait Conscientiousness and the Financial and Growth performance of the small business.

H3a - 3b There is a positive relationship between possessing the trait Openness to experience and the Financial and Growth performance of the small business.

H4a - 4b There is a positive relationship between possessing the trait Agreeableness and the Financial and Growth performance of the small business.

H5a - 5b There is a negative relationship between possessing the trait Neuroticism and the Financial and Growth performance of the small business.

Cronbach-alpha coefficients were calculated to assess the reliability of the measuring instrument. The operationalisation of the various constructs identified as well as the Cronbach-alpha coefficients for each of these constructs are summarised in Table 3. Cronbach-alpha coefficients of greater than 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978) were reported for the two dependent variables. The scales measuring these factors were thus considered reliable. Similarly, the coefficients reported for Extraversion (0.704) and Openness to experience (0.708) suggest that the scales measuring these independent variables were reliable. However, coefficients reported for Conscientiousness (0.666) and Agreeableness (0.600) were less than the lower limit of 0.70. This lower limit may be reduced to 0.60 in certain cases (Hair et al., 2006). Therefore, satisfactory evidence of reliability for these factors was reported. The Cronbachalpha coefficient for Neuroticism was 0.528, suggesting that the scale measuring this factor showed evidence of poor reliability. However, because this scale had been sourced from an existing measuring instrument, which was shown to be reliable in previous studies, it was decided to retain this factor for further analysis to avoid jeopardising content validity.

5.3 Descriptive statistics and correlations

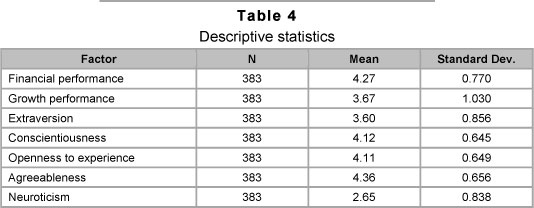

For discussion purposes response categories on the 5-point Likert-type scale were categorised as disagree (0.0-2.9), neutral (3.0-3.9) and agree (4.0-5.0), with disagree corresponding with options 1 and 2 on the 5-point Likert-type scale, neutral corresponding with option 3 and agree with options 4 and 5. From Table 4 it can be seen that Agreeableness produced the highest mean score (4.36), which implies that the respondents participating in this study perceived themselves as individuals who were kind, helpful and forgiving in nature.

Neuroticism (2.65), on the other hand, produced the lowest mean score. The respondents in this study were more likely to disagree with regard to being neurotic. Conscientiousness and Openness to experience produced mean scores of 4.12 and 4.11 respectively, implying that the respondents in this study agreed to possessing these traits. Extraversion produced a mean score of 3.60, implying neutrality in terms of possessing this trait.

With regard to the dependent variables, mean scores of 3.67 and 4.27 were reported for Growth performance and Financial performance respectively. For these dependent variables, a t-test revealed that no significant differences exist in the mean scores reported by owners of small businesses that had been operating for more than 3 years and those that had been operating for less. The respondents participating in this study were neutral regarding their business showing growth, but agreed that their business was profitable and financially secure.

From Table 5 it can be seen that all the personality dimensions, except for Agreeableness and Neuroticism, showed statistically significant positive correlations with Financial performance. Statistically significant correlations were also returned between all the personality dimensions, except for Agreeableness and Growth performance. Neuroticism produced a negative relationship, whereas the other dimensions showed a positive correlation with Growth performance. Although these correlations are statistically significant, the low r values indicate weak to negligible relationships. A statistically significant strong positive relationship is, however, reported between Financial performance and Growth performance.

5.4 Multiple regression analysis

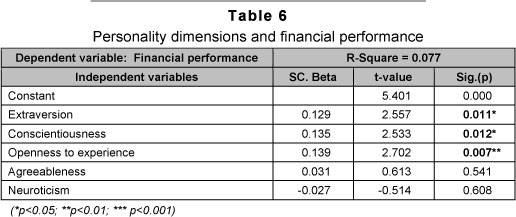

Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to assess whether the personality dimensions Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Openness to experience, Agreeableness and Neuroticism, exerted a significant influence on the dependent variables, Financial performance and Growth performance.

The personality dimensions investigated in this study explained 7.7 per cent of the variance in Financial performance (see Table 6). The independent variables Extraversion (2.557; p<0.05), Conscientiousness (2.533; p<0.05) and Openness to experience (2.702; p<0.01), had a positive linear relationship with the dependent variable Financial performance. No relationship was returned between Agreeable-ness and Neuroticism, and Financial performance. Support is thus found for hypotheses Hla, H2a and H3a but not for H4a and H5a.

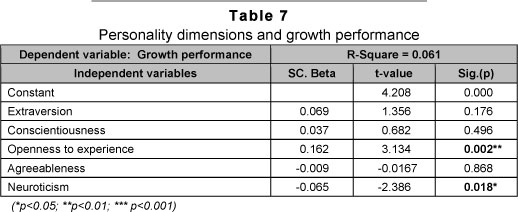

The personality dimensions investigated in this study explained 6.1 per cent of the variance in Growth performance. From Table 7 below it can be seen that a positive linear relationship was found between Openness to experience (3.134; p<0.01) and the Growth performance of the business. A negative linear relationship was, however, found between

Neuroticism (-2.386; p<0.01) and the Growth performance of the business. Against this background, the hypotheses H3b and H5b are supported, whereas Hlb, H2b and H4b are not.

6 Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to investigate whether relationships existed between possessing certain personality traits and small business success. Personality was measured using the dimensions of the five-factor model of personality, namely Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Openness to experience, Agreeableness and Neuroticism. Small business success was measured in terms of both the growth and the financial performance of the small business. Evidence of construct and discriminant validity for the measuring scales was ascertained, and satisfactory evidence of reliability was found for all factors except Neuroticism. Results pertaining to this personality dimension should be interpreted with caution.

The small-business owners participating in this study perceived themselves to be agreeable, conscientious and open to experience. They were neutral with regard to being extraverted, but disagreed about being neurotic. The respondents reported being neutral regarding their business showing growth, but agreed that their business was profitable and financially secure. Apart from Agreeableness and Neuro-ticism, the other personality dimensions were significantly and positively correlated to Financial performance. Except for Agree-ableness, all the personality dimensions investigated in this study were significantly correlated to Growth performance, with all correlations being positive except for Neuroticism.

The results of the multiple regression analysis show a significant positive relationship between possessing the personality traits Extraversion, Conscientiousness and Openness to experience and the dependent variable Financial performance. In other words, the more extraverted, conscientious and open to experience small-business owners are, the more likely they are to perceive their business as being successful, profitable and financially secure. Small-business owners are more likely to have a business that performs financially if they are talkative, uninhibited, outgoing, energetic, loud and sociable; thorough, careful, organised, not easily distracted, follow through on plans made and do things efficiently, as well as those who are ingenious, inventive, reflective, have an active imagination and like playing with ideas, than are those who do not possess these personality traits. No relationship was reported between the personality traits Agreeableness or Neuroticism and Financial performance. Whether small-business owners possess these traits or not has no influence on their business performing financially.

Barrick and Mount (1991), and Barrick et al. (2001) report Extraversion to be a valid predictor of successful performance in managerial occupations. Similarly, Barrick and Mount (2005) have found Extraversion to be linked to job success in occupations where a substantial portion of the job involves influencing others. Given that small-business owners operate in managerial positions and have influence over others (employees), the positive influence of Extraversion on Financial performance reported in this study supports previous findings. The findings of this study do, however, contradict those of Thal and Bedingfield (2010), who found little support for Extraversion being able to identify successful future project managers.

That Conscientiousness is a valid predictor of performance is well supported in the literature (Thal & Bedingfield, 2010; Barrick et al., 2001; Barrick & Mount, 1991). According to Judge et al. (2002), among the five personality dimensions of the five-factor model, Conscientiousness has returned the strongest and most stable correlations across managerial performance criteria and across management settings. The findings of this study in the context of small business management add to this support.

The results show that Openness to experience has a positive influence on both the financial and growth performance of the small business. The more ingenious, inventive and reflective the small-business owner is, as well as being active in imagination and liking to play with ideas, the more likely the business is to be profitable and financially secure as well as experiencing growth in terms of sales turnover, employees and profits. Openness to experience also demonstrated the strongest influence on both the financial and growth performance of the small business. These findings concur with those of Thal and Bedingfield (2010) as well as Nadkarni and Herrmann (2010) who report that Openness to experience is strongly correlated with perceptions of performance, and enhances firm performance. Openness to experience can thus be considered one of the most important personality traits for small business success. Taking cognisance of the operational definitions of the five personality dimensions (see Table 3) investigated in this study, it could be suggested that Openness to experience, namely being ingenious, inventive and reflective, as well as having an active imagination and liking to play with ideas, is the personality dimension most describing that of an entrepreneurial personality. This finding infers that successful small-business owners are entrepreneurial in nature. The findings of this study, however, contrast with those of Barrick and Mount (1991) who found no relationship between Openness to experience and job performance, as well as Barrick et al. (2001), who reported a weak relationship. The finding of this study do, however, concur with Barrick et al. (2001), who concluded that the relationship between Openness to experience and job performance varies depending on criteria and occupational groups.

Neuroticism demonstrates no influence on the Financial performance of the small business. This finding is in contrast to existing research. Although Barrick and Mount (1991) only reported low correlations between Emotional stability (inverse of Neuroticism) and job performance, Thal and Bedingfield (2010) found Emotional stability to be a good predictor of project success, and Barrick et al. (2001) found Emotional stability to be positively correlated with performance criteria in virtually all jobs across organisations and countries. A negative linear relationship is, however, reported between Neuroticism and the Growth performance of the business. The more neurotic the small-business owner is, the less likely his or her business is to experience growth. Small-business owners who worry a lot as well as being depressed and tense, are less likely to have businesses that experience growth in terms of sales turnover, employees and profits. The finding concerning Neuroticism having a negative influence on Growth performance is supported by Nadkarni and Herrmann (2010), who report that Emotional stability, the reverse of Neuroticism, enhances firm performance by fostering strategic flexibility. A small-business owner who is strategically flexible is more likely to adapt to future changes that are necessary for growth. Similarly, Emotional stability has been shown to be a strong predictor of overall leadership performance, whereas Neuroticism has been found to have a significant negative impact on leadership (Barrick & Mount, 2005). Small-business owners who display leadership are more likely than those who do not, to lead their small business into the future by adapting and growing accordingly.

A possible explanation for the findings concerning Neuroticism and the dependent variables Financial and Growth performance could lie in the nature of these success measures and the operational definition of Neuroticism. In this study, Financial performance is the result of how successfully the business is functioning, whereas Growth performance is possibly more the result of the strategic thinking and risk-taking propensity of the small-business owner. A small-business owner who is emotionally stable (not tense and depressive or often worried) is more likely to take advantage of opportunities for change and growth that arise, as well as being positive about the future, than a small-business owner who is neurotic.

No relationship was reported between possessing the personality traits Extraversion, Conscientiousness and Agreeableness, and the dependent variable Growth performance, implying that whether the small-business owner possesses these personality traits or not, has no influence on the growth performance of the business.

The findings of this study find no relationship between Agreeableness and the dependent variables investigated. In the literature, Agree-ableness has consistently been reported as having little influence on performance (Thal & Bedingfield, 2010; Barrick et al., 2001), and Judge et al. (2002) conclude that this personality dimension appears to be the least relevant of the big five traits. Despite some evidence (Barrick et al., 2001) that Agreeableness is a valid predictor of performance among certain occupational groups, it appears that being 'nice' is not a necessity for small business success.

7 Implications

The findings of this study have important implications for researchers, potential and existing small-business owners, and career counsellors. The results pertaining to validity and reliability of the measuring instrument should be noted by researchers. The factor analysis revealed that the items measuring business success loaded onto two factors, Financial performance and Growth performance. This result supports the contention of Zahra (1991) that financial performance and growth performance are different aspects of performance, and each reveals important information. To consider growth and profitability as independent measures of business performance is not uncommon in the literature (Geringer, Frayne & Olsen, 1998; Cubbin & Leech, 1986) and researchers need to take cognisance of both aspects of business performance when measuring business success.

The results of this study suggest that small-business owners high in Extraversion and Conscientiousness, and who are Open to experience are more likely to have successful businesses than those who are not. More specifically, Openness to experience demonstrates the strongest influence on both the financial and growth performance of the small business, and is the only trait that has a positive influence on both these measures of success. Although personality traits are found to remain stable over an individual's lifetime (Llewellyn & Wilson, 2003) and as such are not easily developed, existing small-business owners would do well to develop these traits as far as possible. Where personality traits cannot be developed or changed, small-business owners could employ people with personality traits that complement their own to assist them in managing their business. Future small-business owners should consider the results of this study and decide whether, based on their personality, they are really suited to business ownership.

A basic understanding of the general personality profile of a successful small-business owner also has important implications for career counsellors. By identifying the gaps between a future small-business owner's personality and the personality ideal for a successful small-business owner, steps can be undertaken to manage these discrepancies or close these gaps. It is the role of career counsellors to guide people into suitable career directions, and having knowledge of the personality type most suited to business ownership will enable counsellors to encourage and guide people appropriately.

8 Limitations and future research

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. Firstly, the use of convenience sampling introduces a source of potential bias into the study, as the risk of unintentionally getting responses from a particular group is higher. For example, small-business owners who are more emotionally stable, extraverted, open to experience and agreeable, may possibly be more willing to participate in a survey than those who do not have these personality traits. Furthermore, only small businesses from the Eastern Cape Province participated in the study. Convenience sampling does not lead to representative samples, and therefore the findings of this study cannot be generalised to the entire small business population. In order to make the sample more representative, future studies should attempt to obtain databases from which probability samples of small-business owners throughout South Africa can be drawn.

Another limitation of this study is that the results are based on one-time self-reporting, which potentially leads to common method bias. Meade, Watson and Kroustalis (2007) are of the opinion that common method bias does not necessarily jeopardise the validity of the results of a study. However, it is acknowledged that common assessment methods as well as individual perception, interpretation and opinion could have influenced the results of this study For the purpose of measuring the five personality dimensions in this study, the BFI inventory (Srivastava, 2010) was used. However, the factor analysis revealed that several items intended to measure the various personality dimensions did not load as expected. Furthermore, Neuroticism returned poor evidence of reliability. Questions as to the validity and reliability of the BFI are thus raised. Future studies could make use of other inventories to measure the personality dimensions of the five-factor model. The five-factor model is only one of many potential ways to operationalise personality (Nadkarni & Herrmann, 2010), and other measures could be considered in future studies.

This study is limited to five broad personality dimensions. Disagreement exists as to whether broad personality factors like the big five incorporate all the relevant information to predict performance (Bergner et al., 2010). Each of these broad dimensions is comprised of a small number of narrow traits which can also be used to predict behaviour. However, no consensus exists on the number and nature of these narrow traits (Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006; Llewellyn & Wilson, 2003). It may be that narrower traits will provide a better understanding and more accurate prediction of the relationship between personality and business success. Future studies should strive to identify these narrow traits and investigate whether they are better able to predict business performance than the broad traits used in this study.

This study has investigated the influence of personality on business success. However, many other factors also influence the success of a business, factors relating to the business itself and the conditions under which it operates, such as economic conditions and access to resources, as well as factors relating to the owner as a person, such as education and experience. As such, in addition to personality, other personal influences should be considered when trying to determine whether an individual will be a successful small-business owner or not.

Despite the limitations, the results of this study provide insights into the personality profiles best suited to successful small-business ownership, as well as insights into the relationship between personality and business success. The study lays the foundation for future research into the role of personality in entrepreneurship and as such makes a contribution to this field of study. In conclusion, 'Yes, personality does matter for small business success'.

References

ACS, Z., GLAESER, R., LITAN, L. & FLEMING, S. 2008. Entrepreneurship and urban success. Kansas City, Missouri: Ewing Marion. [ Links ]

BARRICK, M.R. & MOUNT, M.K. 1991. The big five personality dimensions and job performance. Personnel Psychology, 44:1-26. [ Links ]

BARRICK, M.R. & MOUNT, M.K. 2005. Yes, personality matters: moving on to more important matters. Human Performance, 18:359-372. [ Links ]

BARRICK, M.R., MOUNT, M.K. & GUPTA, R. 2003. Meta-analysis of the relationship between five factor model of personality and Holland's occupational types. Personnel Psychology, 56:45-74. [ Links ]

BARRICK, M.R., MOUNT, M.K. & JUDGE, T.A. 2001. Personality and performance at the beginning of the new millennium. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9:9-30. [ Links ]

BARRINGER, B.R. & IRELAND, R.D. 2010. Entrepreneurship: successfully launching new venture, Global Edition (3rd ed.) Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson. [ Links ]

BERGNER, S., NEUBAUER, A.C. & KREUZTHALER, A. 2010. Broad and narrow personality traits for predicting managerial success. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 19(2):177-199. [ Links ]

BOLTON, B. & THOMPSON, J. 2004. Entrepreneurs talent, temperament, technique. Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth Heinemann. [ Links ]

BONO, J.E. & JUDGE, T.A. 2004. Personality and transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89:901-910. [ Links ]

BROWN, T. 1996. Resource orientation, entrepreneurial orientation and growth: how the perception of resource availability affects small firm growth. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University, New Jersey. [ Links ]

BURGER, J.M. 2008. Personality. Available at: http://books.google.co.za/books?id=FVGHOJ=!anddq=what+is+personalityandhl [ [ Links ]accessed 2011 -03-18].

BURNS, P. 2001. Entrepreneurship and small business management. New York, New York: Palgrave. [ Links ]

CALVASINA, R.V., CALVASINA, E.G. & CALVASINA, E.J. 2010. Personal liability and human resources decision making. Journal of Management and Marketing Research, 1:38-49. [ Links ]

CANNELLA, A.A. & MONROE, M.J. 1997. Contrasting perspectives on strategic leaders: towards a more realistic view of top managers. Journal of Management, 23:213-237. [ Links ]

CATTELL, R.B. 1946. The description and measurement of personality. Yonkers, New York: World book. [ Links ]

CHANDLER, G.N. & HANKS, S.H. 1993. Measuring the performance of emerging businesses: a validation study. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(3):223-236. [ Links ]

CHEN, Y. & LAI, M. 2010. Factors influencing the entrepreneurial attitude of Taiwanese tertiary-level business students. Social behaviour and personality, 38(1):1-12. [ Links ]

CHERRY, K.N.D. Overview ofpersonality. Available at: http://psychology.about.com/od/ overviewofpersonality/a/html [ [ Links ]accessed 2011-03-17].

CHILLEMI, S. 2010. Ten steps to self-confidence. Available at: http://stores.lulu.com/staceychil [ [ Links ]accessed 2010-07-27].

COOPER, A.C. 1995. Challenges in predicting new venture performance. In DAHLQVIST, J., DAVIDSSON, P. & WIKLUND, J. 2000. Initial conditions as predictors of new venture performance: a replication and extension of the Cooper et al. study. Enterprise and Innovation Management Studies,1(1):1-17. [ Links ]

COOPER, C.L & PERVIN, L.A. 1998. Personality. Available at: http://books.google.co.za/books?Wl=enandir=andid=QDSSuoERR=fndandpg=PAZasanddq=define+the+five+ factor+model [ [ Links ]accessed 2011-03-17].

COOPER, J. 1998. Individual differences. London: Arnold. [ Links ]

COSTA, P.T & MCCRAE, R.R. 1992. Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO Pi-R) and NEO five factor inventory (NEO FFI) professional manual. Odessa, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources. [ Links ]

COWIE, L. 2007. An investigation into the components impacting the effective functioning of management teams in small businesses. Unpublished honours treatise, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth. [ Links ]

CROMIE, S. 2000. Assessing entrepreneurial inclinations: some approaches and empirical evidence. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 9(1):7-30. [ Links ]

CUBBIN, J. & LEECH, D. 1986. Growth versus profit-maximization: a simultaneous-equations approach to testing the Marris Model. Managerial and Decision Economics, 7:123-131. [ Links ]

DAVIR, D., SADEH, A. & MALACH-PINES, A. 2006. Projects and project managers: the relationship between project managers, personality, project types and project success. Project Management Journal, 37(5):36-48. [ Links ]

DEAKINS, D. & FREEL, M. 2009. Entrepreneurship and small firms (5th ed.) London: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

DOUGLAS, L.G.N.D. Entrepreneurs and personality. Available at: http://www.managementprychology.com/article.php [ [ Links ]accessed 2011-03-02].

EYBERS, C. 2010. Copreneurs in South African small and medium-sized family businesses. Unpublished masters dissertation, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa. [ Links ]

FARRINGTON, S. 2009. Sibling Partnership in South Africa small and medium-sized family businesses. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa. [ Links ]

FINKELSTEIN, S. & HAMBRICK, D.C. 1996. Strategic leadership: top executives and their effects on organisations. In NADKARNI, S. & HERRMANN, P. 2010. CEO performance, strategic flexibility, and firm performance: the case of the Indian business process outsourcing industry. Academy of Management Journal, 53(5):1050-1073. [ Links ]

FISKE, D.W. 1949. Consistency of the factorial structures of personality rating from different sources. In THAL, A.E. Jr. & BEDINGFIELD, J.D. 2010. Successful project managers: an exploratory study into the impact of personality. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 22(2):243-259. [ Links ]

FOULKROD, K.H., FIELD, C. & BROWN, C.V.R. 2009. Trauma surgeon personality and job satisfaction results from a national survey. Paper read at the Austin Trauma and Critical Care Conference, Austin, Texas, 4 June. [ Links ]

GERINGER, J.M., FRAYNE, C.A. & OLSEN, D. 1998. Rewarding growth or profit? Top management team compensation and governance in Japanese MNEs. Journal of International Management, 4:289-309. [ Links ]

GOLDBERG, L.R. 1993. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist, 48:26-34. [ Links ]

GORDON, R.G. 2002. Personality, Great Britain: Routledge. [ Links ]

HAIR, J.F., BLACK, W.C., BABIN, J.B., ANDERSON, R.E. & TATHAM, R.L. 2006. Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.) Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson/Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

HASLAM, N. 2007. Introduction to personality and intelligence. Available: http://books.google.co.za/books?/=what=is=personalityandhl [ [ Links ]accessed 2011-03-18].

HETLAND, H. MJELDHEIM, G & JOHNSEN, T.B. 2008. Followers' personality and leadership. Available: http://www.entrepreneur.com/tradejournals/article/print/html [ [ Links ]accessed 3 March 2011].

HILLER, N.J. & HAMBRICK, D.C. 2005. Conceptualizing executive hubris: the role of (hyper-) core self-evaluations in strategic decision-making. Strategic Management Journal, 26:297-319. [ Links ]

HORNADAY, J.A. 1982. Research about living entrepreneurs. In KENT, C.A, SEXTON, D.A. & VESPER, K.H. 1982. Encyclopaedia of entrepreneurship. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

HOUSE, R.J. & HOWELL, J.M. 1992. Personality and charismatic leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 3:81108. [ Links ]

JOHN, O.P. 1990. The big five factor taxonomy: dimensions of personality in the natural language and questionnaires. In PERVIN, L.A. 1994. Handbook of personality: theory and research. New York, New York: Guilford. [ Links ]

JUDGE, T.A, HIGGINS, C.A, THORSEN, C.J & BARICK, M.R. 1999. The big five personality traits, general mental ability and career success across the span. Personnel Psychology, 53(3):621-652. [ Links ]

JUDGE, T.A., HELLER, D. & MOUNT, M.K. 2002. Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3):530-541. [ Links ]

JUDGE, T.A., BONO, J.E., ILIES, R. & GEHARDT, M.W. 2002. Personality and leadership: a qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4):765-780. [ Links ]

KROON, J. 2004. Entrepreneurship: start your own business, Cape Town: Kagiso Education. [ Links ]

KURATKO, D.F. & HODGETTS, R.M. 2007. Entrepreneurship theory, process, practice (7th ed.) Canada:Thomson. [ Links ]

KURATKO, D.F. 2009. Entrepreneurship: a contemporary approach (8th ed.) Mason, Ohio: South-Western Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

LLEWELLYN, D.J. & WILSON, K.M. 2003. The controversial role of personality in entrepreneurial psychology. Available: http://www.emeraldinsight.com/insight/viewcontentitem [ [ Links ]accessed 7 March 2011].

LUMPKIN, G.T. & DESS, G.G. 1996. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1):135-172. [ Links ]

MAHADEA, D. 2001. Similarities and differences between male and female entrepreneurial attributes in manufacturing firms in the informal sector in Transkei. Development Southern Africa, 18(2):189-199. [ Links ]

MCCRAE, R.R. & COSTA, P.T., Jr. 1997. Personality trait structures as a human universal. American Psychologist, 52:509-516. [ Links ]

MCCRAE, R.R. & COSTA, P.T. 1980. Openness to experience and ego level in Loevinger's sentences completion test: dispositional contribution to developmental models of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39:1179-1190. [ Links ]

MCGRAE, R.R. 1990. Traits and trait names: how well is openness represented in natural languages? European Journal of Personality, 4:119-129. [ Links ]

MEADE, A.W., WATSON, A.M. & KROUSTALIS, S.M. 2007. Assessing common methods bias in organizational research. Paper presented at the 22nd Annual Meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, New York. [ Links ]

NADKARNI, S. & HERRMANN, P. 2010. CEO performance, strategic flexibility, and firm performance: the case of the Indian business process outsourcing industry. Academy of Management Journal, 53(5):1050-1073. [ Links ]

NIEMAN, G. & NIEUWENHUIZEN, C. (eds.) 2009. Entrepreneurship: a South African perspective (2nd ed.) Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

NIEMAN, G., HOUGH, J. & NIEUWENHUIZEN, C. 2003. Entrepreneurship: a South African perspective, Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

NORMAN, W.T. 1963. Towards an adequate taxonomy of personality attributes: replicated factor structure in peer nomination personality ratings. In THAL, A.E. Jr. & BEDINGFIELD, J.D. 2010. Successful project managers: an exploratory study into the impact of personality. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 22(2):243-259. [ Links ]

NUNNALLY, J. 1978. Psychometric theory. (2nd ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

OZER, D.J. & BENET-MARTÍNEZ, V. 2006. Personality and the prediction of consequential outcomes. Annual Review Psychology, 57:8.1-8.21. [ Links ]

RAAB, G, STEDHAM, Y & NEUNER, M. 2005. Entrepreneurial Potential: an exploratory study of business students in the U.S. and Germany. Journal of business and Management, 11(2):71-88. [ Links ]

RAMANA, C.V., ARYASRI, A.R. & NAGAYYA, D. 2008. Entrepreneurial success in SMEs based on financial and non-financial parameters. The Icfai University Journal of Entrepreneurship Development, 5(2):32-48. [ Links ]

ROTHSTEIN, M.G. & GOFFIN, R.D. 2006. The use of personality measures in personnel selection: what does current research support? Human Resource Management Review, 16:155-180. [ Links ]

SALGADO, J.F. 2003. Predicting job performance using FFM and non-FFM personality measures. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, 76(3):323-346. [ Links ]

SCARBOROUGH, N.M. 2011. Essentials of entrepreneurship and small business management: global edition (6th ed.) Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson. [ Links ]

SCARBOROUGH, N.M., WILSON, D.L. & ZIMMERER, T.W. 2009. Effective small business management: an entrepreneurial approach (9th ed.) Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

SMALL BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT IN SOUTH AFRICA. 2009. Available at: http://www.africa.fnst-freiheit.org/news/sbp-alert-smme-development-in-sa-august-09-digital.pdf [ [ Links ]accessed 2011-06-19].

SOETANTO, D.P., PRIBADI, H. & WIDYADANA. G.A. 2010. Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions among university students. The IUP Journal of Entrepreneurship Development, VII(1&2):23-37. [ Links ]

SPSS INC. 2008. SPSS® 16.0 for Windows, Release 16.0, Copyright© by SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois: SPSS. [ Links ]

SRIVASTAVA, S. 2010. Measuring the big five personality factors. Available at: http//www.uroregon.edu/-sanjay/bigfive.html [ [ Links ]accessed 2010-01-31].

TETT, R.P., JACKSON, D.N. & ROTHSTEIN, M. 1991. Personality measures as predictors of job performance: a meta-analytic review. Personnel Psychology, 44(4):703-742. [ Links ]

THAL, A.E. Jr. & BEDINGFIELD, J.D. 2010. Successful project managers: an exploratory study into the impact of personality. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 22(2):243-259. [ Links ]

TIMMONS, J.A & SPINELLI, S. 2009. New venture creation, entrepreneurship for the 21st century, New York, New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

TSAI, W., MACMILLAN, I. & LOW, M. 1991. Effects of strategy and environment on corporate venture success in industrial markets. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(1):9-28. [ Links ]

VAN AARDT, I., VAN AARDT, C. BEZUIDENHOUT, S. & MUMBA, M. 2008. Entrepreneurship and new venture management. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

VENTER, V., URBAN, B. & RWIGEMA, H. 2008. Entrepreneurship: theory in practice. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

WAITE, M. & HAWKER, S. 2009. Oxford paperback dictionary and thesaurus. New York, New York: Oxford. [ Links ]

WEITEN, W. 2010. Psychology: themes and variations. Belmont, California: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

WITT, L.A., BURKE, L.A., BARRICK M.R. & MOUNT, M.K. 2002. The interactive effects of conscientiousness and agreeableness on job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1):164-169. [ Links ]

ZAHRA, S. 1991. Predictors and financial outcomes of corporate entrepreneurship: an explorative study. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(4):259-285. [ Links ]

Accepted: July 2012