Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versión On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.15 no.4 Pretoria ene. 2012

ARTICLES

Entrepreneurial attributes of undergraduate business students: a three country comparison revisited

Shelley M FarringtonI; Danie JL VenterII; Christine R SchrageIII; Peter O van der MeerIV

IDepartment of Business Management, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

IIUnit for Statistical Consultation, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

IIIDepartment of Marketing, University of Northern Iowa

IVUtrecht School of Ecomymics, Utrecht University

ABSTRACT

In 2001/2002 a study was undertaken to establish whether significant differences existed between the levels of development of several entrepreneurial attributes, as perceived by undergraduate business students from three universities in three different countries. The rationale was that, if entrepreneurial attributes could be identified as more developed in one country than in another, solutions could be provided for developing these attributes in others. The primary objective of this study is to investigate and compare the levels of development of entrepreneurial attributes of undergraduate business students in the present study (2010) to the levels of development reported by undergraduate business students in the 2001/2002 study.

Cronbach alpha coefficients were calculated to assess the reliability of the measuring instrument and t-tests to establish significant differences. Cohen's d statistics were calculated to establish practical significance. The findings suggest that the educational environment and entrepreneurship education policy of the Dutch university participating in this study could provide solutions as to how entrepreneurial attributes among students could be developed further.

Key words: entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial attributes and entrepreneurship education

JEL: L260

1 Introduction and research objectives

According to Mueller (2004) and Shane (1992), the prevalence of entrepreneurial attributes varies across countries and cultures. Factors contributing to these differences are culture, level of economic development of the country, and political-economic traditions (Mueller, Thomas & Jaeger, 2002). Against this background in 2001/2002 Van Eeden, Louw and Venter (2005) undertook a study with the main objective being to report on the levels of development of undergraduate business students' entrepreneurial attributes (personality traits, characteristics and skills) in three different countries. They also wanted to establish whether significant differences exist amongst these countries in respect of the development of these attributes. The reasoning was that if entrepreneurial attributes could be identified as more developed in one country than another, that country could provide solutions as to how to develop such attributes in other countries.

The results of that study (2001/2002) reported that the order of the four most developed entrepreneurial attributes differed for each of the three participating countries. Two attributes, however, Overcoming failure and High energy level, were among the four most developed attributes in all three countries. South African students and students from the United States of America (USA) had three of the top four most developed attributes in common. Although for the Netherlands the order of the least developed attributes differed slightly, the four lowest scoring attributes in all three countries were the same, namely Continuous learning, Knowledge-seeking, Initiative and responsibility, and Communications ability. Furthermore, for nine of the entrepreneurial attributes under investigation, significant differences existed between the mean scores reported by all three countries, with the American sample scoring significantly higher means than the other countries on the levels of development (Van Eeden et al., 2005).

Given the increased attention over the last decade to the development of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship education and Entrepreneurship as an academic discipline (Haase & Lautenschläger, 2011; Nishimura & Tristan, 2011; Soetanto, Pribadi & Widyadana, 2010; Herrington, Kew & Kew, 2009), the aim of this study is to revisit the levels of development of entrepreneurial attributes among undergraduate business students so that improvements to these levels, since 2001/2002, can be established. By using the same measuring instrument and a sample of students from the same three universities as to the study done in 2001/2002, it is hoped that where improvements or changes are evident, didactical solutions can be identified and shared among all. Furthermore, few studies have investigated entrepreneurial characteristics collectively to profile individuals within countries (Tajeddini & Mueller, 2009:7), whereas this study attempts to do just that.

To advance entrepreneurial activity in a country it is essential for the population to possess a particular set of attributes (i.e. personality traits, skills, aptitudes and desires) (Thomas & Mueller, 2001; Krueger & Brazeal, 1994) and as the prevalence of these attributes among a given population increases, so too will the likelihood of entrepreneurial behaviour and in turn entrepreneurial activity in that country (Mueller, 2004). According to Gurol and Atsan (2006), these entrepreneurial attributes can be developed through educational programmes. For example, Mahadea (2001: 193) suggests that an individual's capacity to take risks can be nurtured and developed through appropriate training. According to Chen and Lai (2010), potential entrepreneurs should be developed while still students. Fostering entrepreneurship among students has become an important topic among universities, governments and researchers (Venesaar, Kolbre & Piliste, 2006). Through entrepreneurial education the necessary skills and confidence to undertake entrepreneurial activity can be developed (Fatoki, 2010:92; Urban, Botha & Urban, 2010:135), but it is important for educational institutions to know which skills and competencies to develop when educating future entrepreneurs (Venesaar et al., 2006).

Against this background, the primary objective of this study is to investigate and compare the entrepreneurial attributes of undergraduate business students in three different countries at two different points in time. The levels of development of entrepreneurial attributes of undergraduate business students in the present study (2010) are compared to the levels reported by undergraduate business students in a previous study (2001/2002). For the purpose of this study entrepreneurial attributes refer to personality traits, characteristics and skills commonly associated with entrepreneurs, whereas 'undergraduate business students' refers to students completing business-related modules at undergraduate levels. For convenience, the three countries chosen to participate in the study were the same as those that participated in the 2001/2002 study, namely South Africa, the USA and the Netherlands.

The purpose of this study was not to develop and test hypotheses, but to establish the extent to which entrepreneurial attributes evident among the undergraduate business students of 2010 have changed compared to those of undergraduate business students of 2001/2002. Thus, this study explores the extent to which business students possess more or fewer entrepreneurial attributes and consequently entrepreneurial potential than their counterparts in 2001/2002.

2 Entrepreneurial attributes

Numerous attributes (traits, characteristics and skills) are associated with entrepreneurial behaviour and entrepreneurial success (Deakins & Freel, 2009; Ramana, Aryasri & Nagayya, 2008; Mahadea, 2001; Entrialgo, Fernandez & Vazquez, 2000; McClleland, 1961). It is these entrepreneurial attributes that distinguish entrepreneurs from others, and individuals who possess them may be predisposed or more likely to engage in entrepreneurial activities (Raab, Stedham & Neuner, 2005; Cromie, 2000). In recent years there has been considerable interest and debate over entrepreneurial character (traits) as a predictor to engage in entrepreneurial activity (Tajeddini & Mueller, 2009; Mueller, 2004). Attempts to predict entrepreneurial behaviour using trait approaches have delivered poor results (Kristiansen & Indarti, 2004; Krueger, Reilley & Carsrud, 2000) and there has been little support for a relationship between personality traits and entrepreneurial activity (Autio, Keeley, Klofsten, Parker & Hay, 2001). Venesaar et al. (2006) assert that it is methodically limiting to focus only on personality traits to explain entrepreneurial initiative. Similarly, Kristiansen and Indarti (2004) contend that although attributes are a factor in predicting entrepreneurial behaviour, an individual's attitude most likely plays a bigger role.

Irrespective of this criticism, the 'attribute' approach, focusing on personal characteristics, has dominated attempts to understand entrepreneurs, and whether an individual's characteristics predict entrepreneurial behaviour (Tajeddini & Mueller, 2009; Raab et al., 2005). Although attitude towards entrepreneurship has emerged as the most important factor influencing intentions to become self-employed, personality traits have an indirect influence on the readiness of the individual to undertake such activities (Lüthje & Franke, 2003). In recent times an interest in personality traits and whether these traits affect the intention to engage in entrepreneurial activity, has resurfaced (Mueller, 2004). Furthermore, psychological characteristics are being recognised as being of great importance in understanding and fostering entrepreneurship, and in assessing entrepreneurial potential (Raab et al., 2005). Nevertheless, many consider the identification and investigation of entrepreneurial attributes a worthless exercise (Ramana et al., 2008; Cromie, 2000), yet the perspective of this article supports those that disagree.

Although several attributes (traits, characteristics and skills) have been identified in the entrepreneurship literature as being associated with entrepreneurial behaviour and success, the focus of this study is on the attributes identified by Van Eeden et al. (2005). This was necessary so that the same entrepreneurial attributes assessed in the 2001/2002 study could be assessed in this (2010) study. As such, an elaborate theoretical overview of the various entrepreneurial attributes associated with entrepreneurs was deemed beyond the scope of this article. The attributes investigated in this study, together with supporting references, are summarised in Table 1.

3 Research design and methodology

3.1 Sample and sampling method

In assessing the entrepreneurial attributes of undergraduate business students, a positivistic research paradigm was adopted. All undergraduate students studying business modules at the participating universities were given the opportunity of voluntarily participating in the study. The sample obtained can thus be described as a convenience sample.

3.2 Measuring instrument and data collection

An existing measuring instrument (Van Eeden et al., 2005; Louw, Du Plessis, Bosch & Venter, 1997) was used to assess the levels of development of several entrepreneurial attributes in the present study. Section A of the questionnaire consisted of 104 statements relating to the entrepreneurial attributes under investigation. The statements were phrased with a possible response continuum linked to a Likert-style five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Using an existing measuring instrument required that the existing operational definitions (Van Eeden et al., 2005) for the various entrepreneurial attributes under investigation be adopted. In some instances the attributes named by Van Eeden et al. (2005) were renamed and the operational definitions rephrased. This was done to more accurately describe the personality traits, characteristics and/or skills being measured. However, the items in the 2010 survey were exactly the same as those used in the 2001/2002 survey. These operational definitions are summarised in Table 2. In Section B of the questionnaire demographic information relating to the gender and age of the respondent, as well as the university attended, was requested.

As in the survey carried out in 2001/2002, in 2010 the measuring instrument was distributed among students at the participating universities during a business class. Students willing to complete the questionnaire could do so during class time or they could return it at a later date.

4 Data analysis and empirical results

4.1 Describing the samples

In 2001/2002, 1 528 undergraduate business students participated in the study. The respondents included 758 South African (SA), 379 American (USA) and 391 Dutch (NED) students. From Table 3 it is evident that for SA and the USA the sample consisted of a satisfactory spread between males and females. This figure is, however, slightly skewed in the Dutch sample, with more males than females participating in the study. In all three countries, the majority of participants fell into the 20-25-year old age group.

In 2010, 623 undergraduate business students participated in the study. A more or less even number of respondents from each country participated. In contrast to the 2001/2002 sample, the distribution of males and females in the USA was uneven, whereas in 2001/2002 this was the case in the Dutch sample. In 2010, both the South African and the Dutch samples contained a satisfactory number of male and female participants. As in the 2001/2002 sample, the majority of participants from all three countries fell into the 20-25-year old age group. South Africa did, however, have a much higher number of respondents in the under 20 age group (40%) relative to the USA (4%) and the Netherlands (17%).

4.2 Item analysis

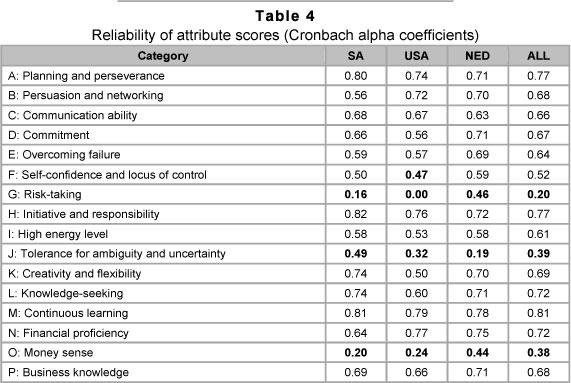

In order to make a comparison between the 2001/2002 results and the results of the current study, the exact items measuring the attributes under investigation had to be used. An exploratory factor analysis was therefore not undertaken and the validity of the measuring instrument based on the 2010 results was not established. However, Cronbach alpha coefficients were calculated for the scales to determine whether the observed scale scores were reliable (internal consistency). Cronbach alpha coefficients (CA) less than 0.50 are deemed unacceptable, while those between 0.50 and 0.60 are regarded as sufficient, and those above 0.70 as acceptable (Nunnally, 1978). According to Sekaran (1992), CA values greater than 0.80 can be regarded as good.

Table 4 shows that low Cronbach alpha coefficients (less than 0.50) were reported for Risk-taking (G), Tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty (J), and Money sense (O). These attributes were consequently excluded from further analysis. Although Self-confidence and locus of control reported a CA of below 0.50 for the American sample, it was decided to retain this attribute because of its close proximity to 0.50 and because of the satisfactory CA levels reported by SA and the Netherlands. There was thus evidence of sufficient reliability for the measuring instrument.

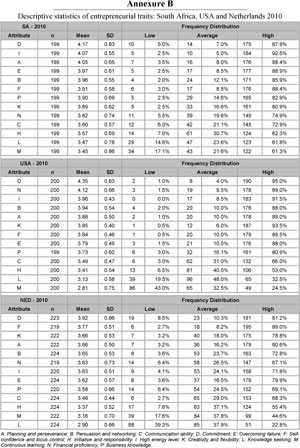

4.3 Descriptive analyses: The levels of development of entrepreneurial attributes

Respondents were requested to assess themselves in terms of the entrepreneurial attributes defined in Table 2. Descriptive statistics relating to these attributes, such as the mean, standard deviation and frequency distributions were calculated to summarise the sample data distribution. This was carried out for both the individual items and the summated attribute scores. Attribute scores were categorised as Low (less than 2.6), Average (between 2.6 and 3.4 inclusive) and High scores (above 3.4). These categories were established to facilitate discussion, and were based on dividing the scale scores so that the Low category corresponded with options 1 and 2 of the five-point Likert scale, the Average category with option 3 and the High category with options 4 and 5 of the response scale. Attribute categories that score Low on average can be considered as underdeveloped, those scoring Average as developed, and those that score High can be considered well-developed. A summary of the descriptive statistics reported for the various attributes is reported in Annexure A (2001/2002) and Annexure B (2010). A detailed discussion of all the entre-preneurial attributes under investigation is not offered in this paper. However, attention will be given to the four most developed attributes, as well as the four least developed attributes.

From Table 5, it is evident that in 2001/ 2002 the order of the four most developed entrepreneurial attributes differed for each of the three countries participating in the study. It is interesting to note that two attributes, Overcoming failure (E) and High energy level (I), were among the four most developed attributes in all three countries. South Africa and the USA had three of the top four most developed attributes in common, Commitment (D), Overcoming failure (E) and High energy level (I). The mean scored by Dutch students for their most developed attribute, Financial proficiency (N), was lower than the means of any of the other four most developed attributes of both SA and the USA. Financial proficiency (N) was also not among the four most developed attributes for either the SA or the USA sample. Persuasion and networking (B), on the other hand, was among the four most developed attributes in the Netherlands and the USA, but not in South Africa.

Although the order was slightly different, the 2010 South African sample reported the same four attributes as most developed as the 2001/2002 South African sample did, namely Commitment, High energy level, Planning and perseverance and Overcoming failure. Commitment was once again perceived as the most developed entrepreneurial attribute. Three of the most developed attributes reported by the 2001/2002 USA sample were also reported as most developed by the 2010 USA sample, namely Commitment, High energy level and Persuasion and networking. As in the SA sample, Commitment was also once again perceived as the most developed entrepreneurial attribute by the 2010 USA sample. In contrast with the 2001/2002 USA sample, the 2010 sample perceived Financial proficiency as one of the four most developed attributes, whereas Overcoming failure was not. Interestingly, none of the top four attributes perceived as most developed among the 2001/2002 Dutch sample were among the top four in the 2010 Dutch sample. As in the 2010 SA and USA sample, Commitment was also perceived as the most developed attribute among the 2010 Dutch sample.

The four least developed attributes in all three countries are summarised in Table 6. From Table 6 it is evident that, during the 2001/2002 study, three of the 13 entrepreneurial attributes investigated obtained mean scores of below the threshold value of 3.4 on the five-point Likert scale for the South African sample, namely Continuous learning (M), Knowledge-seeking (L) and Initiative and responsibility (H). On the other hand, in the USA, only two of the 13 attributes obtained mean scores of below 3.4, namely Continuous learning (M) and Knowledge-seeking (L). In the Netherlands four of the 13 entrepreneurial attributes investigated obtained mean scores of below the threshold value of 3.4, namely Knowledge-seeking (L), Continuous learning (M), Initiative and responsibility (H), and Communication ability (C). These observations suggest that the attributes that scored below the threshold of 3.4 were regarded by the respondents as not being well-developed. Although the order differed slightly for the Netherlands with regard to the least developed attributes, the four lowest scoring attributes in all three countries were the same, namely Continuous learning (M), Knowledge-seeking (L), Initiative and responsibility (H), and Communication ability (C).

Interestingly, the four attributes perceived as least developed by the 2010 samples from all three countries were exactly the same and in the same order as perceived by the 2001/2002 samples. None of these attributes were reported as less than the threshold value of 3.4 for the South African 2010 sample, whereas two attributes were reported as less than the threshold value of 3.4 for the American sample and three for the Dutch sample.

4.4 Significant differences between development of entrepreneurial attributes between 2001/2002 and 2010

The extent to which differences in levels of development of entrepreneurial attributes, as perceived by students participating in the 2001/2002 study versus those in the 2010 study, were significant was established by means of calculating t-tests. In addition, Cohen's d statistics were calculated to establish practical significance.

With the exception of the attributes Commitment and Overcoming failure, the level of development of all the other entrepreneurial attributes subjected to statistical analysis showed significant (albeit of small practical significance) improvement between the 2001/ 2002 and the 2010 South African samples (see Table 7). This implies that South African undergraduate business students in the 2010 sample perceived themselves as possessing these attributes to a greater extent than did those in the 2001/2002 sample.

The results of this study show that for nine of the 13 entrepreneurial attributes subjected to statistical analysis, there was no difference in mean scores between the 2001/2002 and 2010 American samples (see Table 8).

In other words, the 2010 American sample perceived themselves as possessing these entrepreneurial attributes to the same extent as the 2001/2002 sample of students did. Three of the entrepreneurial attributes, namely Overcoming failure, High energy level and Continuous learning, however, reported a significant (albeit of small practical significance) decrease in the level of development between the 2001/2002 and 2010 samples. In other words, students from the 2001/2002 American sample perceived themselves as possessing these attributes to a greater extent than did the 2010 sample. The attribute Financial proficiency was the only attribute that showed a significant (albeit of small practical signifi- cance) improvement from 2001/2002 to 2010. The 2010 sample of students perceived themselves as possessing a greater level of Financial proficiency than the 2001/2002 sample did.

Eight of the 13 entrepreneurial attributes under investigation showed significant improvements between the 2001/2002 and the 2010 Dutch sample (see Table 9). Two of them reported the improvements as being of moderate practical significance. In other words, the 2010 sample of Dutch students perceived themselves as possessing these eight attributes to a greater degree than their 2001/2002 counterparts did.

5 Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to investigate and compare the entrepreneurial attributes of undergraduate business students in three different countries at two different points in time, more specifically to compare the levels of development of these attributes as perceived by a sample of undergraduate business students in 2010 with the levels reported by a sample of undergraduate business students in 2001/2002.

The findings of this study show that the four attributes perceived as most developed by the 2010 South African sample were the same as those reported by the 2001/2002 South African sample. In the case of the USA sample, three of the four attributes perceived as most developed by the 2010 sample were also reported as most developed by the 2001/2002 sample. Financial proficiency was perceived as the second most developed attribute by the 2010 USA sample, but as only the seventh most developed by the 2001/2002 USA sample. None of the top four attributes perceived as most developed among the 2010 Dutch sample were among the top four for the 2001/2002 Dutch sample. When it came to the four most developed attributes, it appears that, in contrast with the 2001/2002 sample, the 2010 South African sample reported no changes; the 2010 USA sample reported one change, whereas the 2010 Dutch sample reported four completely different attributes as being the most developed. This finding suggests that in comparison to the students participating in the 2001/2002 study, some change had occurred in the educational environment of Dutch students participating in the 2010 study, but not in that of the 2010 South African or American students.

Interestingly, Commitment was reported in the 2010 study as being the most developed attribute among the samples from all three countries. Commitment refers to an ability to meet commitments in a timely manner. Students exist in an academic environment which places several demands on them in terms of submitting tasks and assignments according to specified deadlines. One would expect the majority of students at university to possess this attribute. Although the ability to meet commitments in a timely manner is an important entrepreneurial attribute, Farrington, Venter and Neethling (2012) found no relationship between Commitment and entrepreneurial intentions. They concluded that Commitment is not an attribute unique to students with entrepreneurial intentions.

The four attributes perceived as least developed by the 2010 samples from all three countries were exactly the same and in the same order as those perceived by the 2001/2002 samples, namely Continuous learning (M), Knowledge-seeking (L), Initiative and responsibility (H), and Communication ability (C). This implies that students in all three countries perceived the desire to expand personal knowledge and enhance their level of expertise (Continuous learning); the willingness to seek information, ideas, expertise and the assistance of others (Knowledge-seeking); the willingness to take initiative and be responsible (Initiative and responsibility); and the ability to communicate ideas to others (Communication ability) as the least developed attributes. Although not investigated empirically in this study, it is well supported in the literature (see Table 1) that the aforementioned attributes are associated with successful entrepreneurs. Furthermore, in their study among South African business students, Farrington et al. (2012) report significant relationships between possessing the entrepreneurial attributes Continuous learning, Knowledge-seeking, Initiative and responsibility and Communication ability, and the intentions of students to start their own businesses. They conclude that students who possessed these attributes were more likely to embark on entrepreneurial careers than were those who did not possess them. The need for addressing these underdeveloped attributes is thus highlighted.

Instilling the desire to expand personal knowledge and enhance one's level of expertise (Continuous learning), and creating a willingness to seek information, ideas, expertise and the assistance of others (Knowledge-seeking), among business students is a challenging task. It is only when the value of knowledge is internalised that a willingness and desire to pursue it can be stimulated. Educators should strive to develop these attributes by means of practical assignments that require students to seek additional information and assistance from others. In addition, entrepreneurial role models could be invited to address students on the value of continually expanding their personal knowledge and of seeking the assistance and expertise of others. In doing this they would reinforce what students are hearing in their academic studies. Unfortunately the value of knowledge received during academic studies is often recognised by students only retrospectively, once they enter the world of work, where that knowledge is required in practice. The ability to communicate ideas to others (Communication ability) can be developed among business students by increasing the use of interviews, orals and presentations when assessing students. Students should, however, be made aware that the ability to communicate ideas to others requires not only the ability to speak in public, but also the ability to communicate the right information, using the right medium. Furthermore, Initiative and responsibility can be encouraged by rewarding those who are willing to take initiative and be responsible, through either recognition or improved results.

Although the top four developed attributes reported by the 2010 and the 2001/2002 South African sample were the same, the level of development of all but two showed significant improvements from 2001/2002 to 2010. In other words, participating South African undergraduate business students in 2010 perceived themselves as possessing these attributes to a greater extent than the earlier sample. This implies that the levels of confidence of students in terms of possessing these attributes, was higher and that educational efforts to improve these levels had met with some success. The increase was, however, of small practical significance, and further investigation would be recommended to shed some light on possible explanations for this finding.

Although the 2010 American sample perceived themselves as possessing most of the attributes to the same extent that the 2001/2002 sample of students did, the attributes Over-coming failure, High energy level and Continuous learning revealed significant decreases in the level of development between the 2001/2002 and 2010 samples. This implies that the students in the 2010 samples perceived themselves as having the ability to overcome failure and regard it as a learning experience, having the ability to work long hours and stay focused, and having the desire to expand personal knowledge and enhance level of expertise, to a lesser degree than the students participating in the 2001/2002 study. However, the 2010 sample of students perceived themselves as possessing a greater level of Financial proficiency than the 2001/2002 sample.

The severe economic crises experienced in the United States during the period 2008-2010 could provide a possible explanation for the findings of this study. In the midst of a recession, it comes as no surprise that students would have a more negative outlook and consequently be less able to deal with failure, and be less motivated to work long hours and expand their knowledge. Although there is still a focus on developing entrepreneurs in the United States, two long-drawn-out wars, considerable economic distress, and budget cuts at public universities have resulted in decreased positive energy for new business start-ups. Most students in the United States now tend to look for more secure career choices by taking jobs in established companies rather than considering an entrepreneurial venture during or shortly after leaving university. Furthermore, given the financial problems facing the American people, one could expect that students would be more exposed to matters of financial concern, hence raising their knowledge in terms of understanding the financial aspects of business. These circumstances of financial turmoil also provide a possible explanation as to why, in contrast with the South African and Dutch samples, the development of most entrepreneurial attributes investigated in this study remained unchanged between the 2001/2002 and 2010 American samples.

Despite the four most developed attributes being completely different in the 2010 and the 2001/2002 Dutch samples, the majority of attributes under investigation showed significant improvements between the 2001/2002 and the 2010 samples. Two of these attributes, Communication ability and Initiative and responsibility, showed the differences as being of moderate practical significance. Interestingly both the willingness to take initiative and to be responsible, and the ability to communicate ideas to others were reported by Farrington et al. (2012) as being significantly related to the entrepreneurial intentions of students.

The Dutch University participating in this study had no independent Economics Department prior to 2001, and the students participating in the 2001/2002 study were required to complete a business module as part of other studies (mainly Dutch Law). These students were therefore not specifically students of business or economics. This particular Economics Department has grown significantly since 2001, and it now offers several business and entrepreneurship modules. The Dutch students participating in the 2010 study were from the Economics Department or else they came from various other fields of study throughout the university and had undertaken the business module voluntarily. Given that they were business students or had taken the business module because they were interested in the field provides a possible explanation as to why the Dutch students participating in the 2010 study showed higher levels of development of the entrepreneurial attributes under investigation. Another possible explanation for the results of this study could be the recent increased interest in entrepreneurship as a whole in the Nether-lands. Not only has the number of business start-ups grown since 2001, but a focus on entrepreneurship also seems to have increased in the popular media. Becoming an entrepreneur (self-employment) has become more popular as a career choice.

The findings of this study seem to suggest that the educational environment and entrepre-neurship education policy of the Dutch university participating in this study should be investigated further. It is hoped that, by identifying changes implemented during the period 2001/2002 to 2010, possible explanations for the increased levels of entrepreneurial attributes among Dutch students could be found. Once identified, the changes implemented could be of value to educators in entrepreneurship worldwide.

Looking at the demographic profiles (Table 3) of the students participating in the 2010 and the 2001/2002 studies, it can be seen that the South African samples were more or less the same in terms of age and gender, yet the majority of attributes were reported by the 2010 sample as being more developed. It appears that age and gender have not contributed to the changes reported. In contrast, more males formed part of the 2010 USA sample and more females were part of the 2010 Dutch sample than in the 2001/2002 samples. The ages reported by the 2010 USA sample were approximately the same as those in the 2001/2002 sample, whereas more students in the 2010 Dutch sample were over the age of 20 than those in the 2001/2002 sample. It is possible that these differences in demographic profiles could have contributed to the differences in the levels of development of several attributes reported by these two sample groups. It must be pointed out that more males participated in the 2010 US sample, yet several attributes were reported as being less developed by this sample than by the 2001/2002 sample. Similarly, fewer males participated in the 2010 Dutch sample, yet most attributes were reported as being more developed by this sample than by the 2001/2002 group. This could imply that the respondents' gender accounted for the changes in the levels of development reported by these sample groups. However, these claims are not supported empirically in this study, and in seeking explanations for the findings of this study, age and gender together with other demographic factors, such as ethnicity and culture, present an avenue for future research.

6 Implications

According to Fatoki (2010: 93), there is a mismatch between the skills that students develop in higher education and those that they need for survival in the business world. The findings of this study support this suggestion, in that the four least-developed attributes reported by the student respondents from all three countries are attributes commonly associated with successful entrepreneurs. Given the importance of entrepreneurship to the economies of countries, the low levels of development of these attributes are a source of concern.

Universities face a considerable challenge in developing programmes that prepare students for starting new businesses immediately after graduation (Soetanto et al., 2010:34). However, entrepreneurial attributes can be developed by means of educational programmes (Drost, 2010:29; Gerry et al., 2008; Gurol & Atsan, 2006) and it is the responsibility of educational institutions to foster an environment in which these attributes can be developed in students as well as to identify those attributes that are necessary for entrepreneurial success. It is the role of educational institutions not only to equip students with the knowledge to embark on entrepreneurial ventures, but also to develop entrepreneurial attributes, talent and initiative among students.

An environment in which students are able to observe and report on successful entrepreneurial role models, undertake business simulation games, and set up business plans for actual businesses as part of their academic studies would be a step in the right direction. Attendance at workshops on entrepreneurship and entering entrepreneurial competitions offered by both academic and non-academic institutions should also be encouraged among students. The best recommendation is to incorporate and integrate into entrepreneurial education as many different learning experiences as possible that would contribute to the development of traits, characteristics and skills associated with successful entrepreneurs, and to do this as often as possible. However, the most important challenge facing educators of entrepreneurship is not to identify practical ways of developing entrepreneurial attributes among students, but to implement these recommendations within the framework of a traditional academic environment.

7 Limitations and future studies

The findings of this study must be interpreted in light of several limitations. The use of a convenience sampling introduced a source of potential bias into the study and the findings can thus not be generalised to the entire population. Furthermore, when data are collected using self-reporting measures, common method bias could potentially occur. However, Meade, Watson and Kroustalis (2007) contend that the use of self-reporting does not necessarily lead to bias, and in many cases the bias may be so small that it does not jeopardise the validity of the results. The authors acknowledge that common method bias could have influenced the results of this study.

Several limitations can also be identified with the measuring instrument itself. Well-documented entrepreneurial attributes, such as internal locus of control, the need for achievement, problem-solving ability, emotional stability, team ability and innovativeness (Raab et al., 2005; Tajeddini & Mueller, 2009), as well as desire for immediate feedback, future orientation and skill at organising (Scarborough, 2011: 22), are not accounted for or measured in the instrument. Given the objectives of this study, Van Eeden et al.'s (2005) instrument, with its limitations, had to be used. Further, the attributes Risk-taking (G), Tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty (J) and Money sense (O) obtained low Cronbach alpha coefficients and were excluded from further statistical analysis.

In comparing the levels of development of the entrepreneurial attributes at two different points in time, namely in 2001/2002 and 2010, some interesting findings were brought to light. However, given that the samples from the two different time periods were completely different, the findings of this study should be interpreted with caution. In addition, a test of configural invariance did not precede the use of t-tests to assess differences in mean scores.

As indicated earlier, establishing whether demographic factors provide an explanation for the findings in this study presents an avenue for future research. Measuring the levels of development of entrepreneurial attributes of the same sample of respondents at different points in time during the course of their university studies is recommended for future research. However, the methodology associated with longitudinal studies is problematic.

The curriculum and study environments of the participating universities were not specifically considered when undertaking this study. These may, however, be relevant to the interpretation of the findings. According to Tajeddini and Mueller (2009), social context must be considered when explaining differences between entrepreneurs and should be considered in future studies. In this regard, investigating whether significant differences exist between the levels of development of the entrepreneurial attributes reported by the 2010 sample of students in the three different countries, as was done in the 2001/2002 study, would also make for interesting results. However, these findings fall beyond the scope of this article.

The attribute (trait theories) approach has been shown to be useful in explaining why some individuals become entrepreneurs and others do not. However, according to Cromie (2000), personal attributes are important but they are not all-important determinants of behaviour. Similarly, Kiggundu (2002) contends that individual characteristics are inadequate to explain the nature of entrepreneurial success or failure. Several authors propose (Gird & Bagraim, 2008; Krueger & Carsrud, 1993; Ajzen, 1991) that intentions are the best predictors of behaviour, and future research should therefore focus on the entrepreneurial intentions of students as predictors of entrepreneurial activity rather than on entrepreneurial attributes, as has been the case in this study.

Notwithstanding the limitations identified, the findings of this study add to the field of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education. In addition, the entrepreneurial profiles of undergraduate business students in South Africa, the United States and the Netherlands have been outlined.

References

AJZEN, I. 1991. The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50:179-211. [ Links ]

AUTIO, E., KEELEY, R.H., KLOFSTEN, M., PARKER G.J.C. & HAY, M. 2001. Entrepreneurial intent among students in Scandinavia and in the USA. Enterprise and Innovation Management Studies, 2(2):145-160. [ Links ] BARRIER, M. 1995. The changing face of leadership. Nation's business, 83(1):41-42. [ Links ]

BARRINGER, B.R. & IRELAND, R.D. 2008. Entrepreneurship: successfully launching new ventures (2nd ed.). London: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

BARRINGER, B.R. & IRELAND, R.D. 2010. Entrepreneurship: successfully launching new ventures. Global edition (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson. [ Links ]

BOWLER, A. 1995. Entrepreneurship: an introduction. Cape Town: Nasou. [ Links ] BURCH, J.G. 1986. Entrepreneurship. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

BURNS, P. & DEWHURST, J. 1993. Small business and entrepreneurship. London: MacMillan Press. [ Links ]

CALVASINA, R.V., CALVASINA, E.G. & CALVASINA, E.J. 2010. Personal liability and human resources decision-making. Journal of Management and Marketing Research, 1:38-49. [ Links ]

CASSON, M. 1991. The entrepreneur. Great Britain: Gregg Revivals. [ Links ]

CHEN, Y. & LAI, M. 2010. Factors influencing the entrepreneurial attitude of Taiwanese tertiary-level business students. Social Behaviour and Personality, 38(1): 1-12. [ Links ]

CHILLEMI, S. 2010. Ten steps to self-confidence. Available at: http://stores.lulu.com/staceychil [ [ Links ]accessed 2010-07-27].

CROMIE, S. 2000. Assessing entrepreneurial inclinations: some approaches and empirical evidence. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 9(1):7-30. [ Links ]

CUDMORE, B.A., PATTON, J., NG, K. & MCCLURE, C. 2010. The millennials and money management. Journal of Management and Marketing Research, 4:1-28. [ Links ]

DE ANGELIS, S.F. & HAYES, B.C. 2010. The enterprise resilience management. Available at: http://enterpriseresilienceblog.typepad.com [ [ Links ]accessed 2010-07-27].

DEAKINS, D. & FREEL, M. 2009. Entrepreneurship and small firms (5th ed.). London: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

DROST, E.A. 2010. Entrepreneurial intentions of business students in Finland: implications for education. Advances in Management, 3(7):28-35. [ Links ]

ENTRIALGO, M., FERNANDEZ, E. & VAZQUEZ, C. 2000. Characteristics of managers as determinants of entrepreneurial orientation: some Spanish evidence. Enterprise and Innovation Management Studies, 1(2):187-205. [ Links ]

FARRINGTON, S. M., VENTER, D. & NEETHLING, A. 2012. Entrepreneurial attributes and intentions: perceptions of South African business science students. Management Dynamics, 21(3):17-32. [ Links ]

FARRINGTON, S. M., VENTER, D., NEETHLING, A. & LOUW. M. 2010. Investigating the entrepreneurial attributes of undergraduate business students at selected tertiary institutions in South Africa. Paper read at The 3rd Annual International Conference on Entrepreneurship, Wits Business School, Johannesburg, 20-21 October. [ Links ]

FATOKI, O.O. 2010. Graduate entrepreneurial intention in South Africa: motivations and obstacles. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(9):87-98. [ Links ]

GERDES, L.C. 1988. The developing adult (2nd ed.). Durban: Butterworths. [ Links ]

GERRY, C., MARQUES, C.S. & NOGUEIRA, F. 2008. Tracking student entrepreneurial potential: personal attributes and the propensity for business start-ups after graduation in a Portuguese university. Available at: http://www.springerlink.com/index/5t5388803n41411w.pdf [ [ Links ]accessed 2010-07-28].

GIRD, A. & BAGRAIM, J.J. 2008. The theory of planned behaviour as predictor of entrepreneurial intent amongst final-year university students. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(4):711-724. [ Links ]

GOODMAN, J.P. 1994. What makes an entrepreneur. IAC, 16(10):29. [ Links ]

GUROL, Y.Y. & ATSAN, N. 2006. Entrepreneurial characteristics amongst university students. Some insights for entrepreneurship education and training in Turkey. Education and Training, 48(1):25-38. [ Links ]

HAASE, H. & LAUTENSCHLÄGER, A. 2011. Career choice motivation of university students. International Journal of Business Administration, 2(1):2-13. [ Links ]

HELLRIEGEL, D., JACKSON, S.E. & SLOCUM, J.W. 1999. Management (8th ed.). Cincinnati: SouthWestern College. [ Links ]

HERRINGTON, M., KEW, J. & KEW, P. 2009. Global entrepreneurship monitor 2008. Cape Town: UCT Centre for Innovation and Entrepreneurship. [ Links ]

JULIENTI, L., BAKAR A. & AHMAD, H. 2010. Assessing the relationship between firm resources and product innovation performance. Business Process Management Journal, 16(3):420-435. [ Links ]

KALUWASHA, C. 2009. The seven common attributes of a true entrepreneur. Available at: http://ezinearticles.com/?The-7-Common-Attributes-of-a-True-Entrepreneurandid=1870258 [ [ Links ]accessed 2010-07-27].

KIGGUNDU, M.N. 2002. Entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship in Africa: what is known and what needs to be done. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 7(3):239-258. [ Links ]

KREITNER, R. & KINICKI, A. 1998. Organisational behaviour (4th ed.). Chicago: Richard D. Irwin. [ Links ]

KRISTIANSEN, S. & INDARTI, N. 2004. Entrepreneurial intention among Indonesian and Norwegian students. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 12(1):55-78. [ Links ]

KROON, J. & MOOLMAN, P.L. 1991. Entrepreneurskap. Potchefstroom: Haum-De Jager. [ Links ]

KRUEGER, N. F. & BRAZEAL, D. V. 1994. Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(3):91-104. [ Links ]

KRUEGER, N.F. & CARSRUD, A.L. 1993. Entrepreneurial intentions: applying the theory of planned behaviour. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 5:315-330. [ Links ]

KRUEGER, N.F., JR., REILLY, M.D. & CARSRUD, A. L. 2000. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15:411-432. [ Links ]

KURATKO, D.F. 2009. Entrepreneurship: a contemporary approach (8th ed.). Mason, Ohio: South-Western Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

LOUW, L., DU PLESSIS, A.P., BOSCH, J.K. & VENTER, D.J.L. 1997. Empirical perspectives on the entrepreneurial traits of undergraduate students at the University of Port Elizabeth: an exploratory study. Management Dynamics, 6(4):73-90. [ Links ]

LÜTHJE, C. & FRANKE, N. 2003. The 'making' of an entrepreneur: testing a model of entrepreneurial intent among engineering students at MIT. R and D Management, 33(2):135-147. [ Links ]

MAHADEA, D. 2001. Similarities and differences between male and female entrepreneurial attributes in manufacturing firms in the informal sector in Transkei. Development Southern Africa, 18(2):189-199. [ Links ]

MANKELWICZ, J. & KITAHARA, R. 2010. Numbers, quantification and the amplification of weak strategic signals. Journal of Management and Marketing Research, 5:1-16. [ Links ]

MARIANI, M. 1994. The young and the entrepreneurial. Occupational Outlook Quarterly, Fall:3-9. [ Links ]

MARVIN, L. & JONES, I .S. 2010. Social/Interpersonal skills in business: in field, curriculum and student perspectives. Journal of Management and Marketing Research, 1:1-13. [ Links ]

MARX, S., VAN ROOYEN, D.C., BOSCH, J.K. & REYNDERS, H.J.J. (eds) 1998. Business management (2nd ed.). Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

MCCLELLAND, D.C. 1961. The achieving society. Princeton UP, Princeton. [ Links ]

MEADE, A. W., WATSON, A. M., & KROUSTALIS, S. M. 2007. Assessing common methods bias in organizational research. Paper presented at the 22nd Annual Meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, New York. [ Links ]

MING, H. H. 2009. Human centric knowledge seeking strategies: a stakeholder perspective. Available at: http://www.emeraldinsight.com/journals.htm?articleid=1801351andshow=abstract [ [ Links ]accessed 2010-07-26]. MUELLER, S. L. 2004. Gender gaps in potential for entrepreneurship across countries and cultures. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 9(3):199-216. [ Links ]

MUELLER, S.L., THOMAS, A.S. & JAEGER, A.M. 2002. National entrepreneurial potential: the role of culture, economic development and political history. Adv Int Manage, 14:221-257. [ Links ]

MUGSHOT, R. 2010. Successful people oriented management and human relations. Available at: http://orglearn.org/career_success_blog/tag/personal-attributes/ [ [ Links ]accessed 2010-07-26].

MUSHONGA, B.L.B. 1981. African small scale entrepreneurship with special reference to Botswana. Unpublished dissertation, Gaborone, University of Botswana and Swaziland. [ Links ]

NIEMAN, G. & BENNET, A. (eds) 2005. Business Management: a value chain approach (2nd ed.). Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

NIEMAN, G. & NIEUWENHUIZEN, C. (eds) 2009. Entrepreneurship: a South African perspective (2nd ed.). Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

NISHIMURA, J.S. & TRISTAN, O.M. 2011. Using the theory of planned behavior to predict nascent entrepreneurship. Academia, Revista Latinoamercana de Administración, 46:55-71. [ Links ]

NITIKINA J. C. 2007. Communication skills article. Available at: http://wwwWikihow.com/Develop-Good-Communication-Skills [ [ Links ]accessed 2010-07-26].

NUNNALLY, J. 1978. Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

PRYOR, M.G., TOOMBS, L., ANDERSON, D. & WHITE, J.C. 2010. What management and quality theories are best for small businesses. Journal of Management and Marketing Research, 3:1-12. [ Links ]

RAAB, G., STEDHAM, Y. & NEUNER, M. 2005. Entrepreneurial potential: an exploratory study of business students in the U.S. and Germany. Journal of Business and Management, 11(2):71-88. [ Links ]

RAMANA, C.V., ARYASRI, A.R. & NAGAYYA, D. 2008. Entrepreneurial success in SMEs based on financial and non-financial parameters. The Icfai University Journal of Entrepreneurship Development, 5(2):32-48. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, F.L. 2010. Using knowledge to improve preparation of construction projects. Journal of Business Process Management, (16)3:361-373. [ Links ]

SCARBOROUGH, N.M. 2011. Essentials of entrepreneurship and small business management, global edition (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson. [ Links ]

SCARBOROUGH, N.M., WILSON, D.L. & ZIMMERER, T.W. 2009. Effective small business management: an entrepreneurial approach (9th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

SEKARAN, U. 1992. Research methods for business: a skill building approach (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

SHANE, SA. 1992. Why do some societies invent more than others. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(1): 29-46. [ Links ]

SIROPOLIS, N.C. 1990. Small business management: a guide to entrepreneurship (4th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

SOETANTO, D.P., PRIBADI, H. & WIDYADANA. G. A. 2010. Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions among university students. The IUP Journal of Entrepreneurship Development, VII(1and2):23-37. [ Links ]

TAJEDDINI, K. & MUELLER, S.I. 2009. Entrepreneurial characteristics in Switzerland and the UK: a comparative study of techno-entrepreneurs. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 7:1-25. [ Links ]

THOMAS, A.S. & MUELLER, S.L. 1999. Are entrepreneurs the same across cultures? Available at: http://www.usasbe.org/knowledge/proceedings/1998/22-Thomas.PDF [ [ Links ]accessed 2010-07-26].

THOMAS, A.S. & MUELLER, S.L. 2001. A case for comparative entrepreneurship: assessing the relevance of culture. Journal of International Business Studies, 31(2):287-301. [ Links ]

TIMMONS, J.A. & SPINELLI, S., JR. 2007. New venture creation - entrepreneurship for the 21st century, international edition (7th ed.). London: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

TIMMONS, J.A. & SPINELLI, S., Jr. 2009. New venture creation - entrepreneurship for the 21st century (8th ed.). Boston: Irwin McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

URBAN, B., BOTHA, J.B.H. & URBAN, C.O.B. 2010. The entrepreneurial mindset. Kempton Park: Heinemann Publishers. [ Links ]

VAN EEDEN, S.M., LOUW, L. & VENTER, D. 2005. Entrepreneurial traits of undergraduate commerce students: a three-country comparison. Management Dynamics, 14(3):26-43. [ Links ]

VAN VUUREN, J.J. 1997. Entrepreneurship education and training: a prospective content model. Unpublished paper, University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

VENESAAR, U., KOLBRE, E. & PILISTE, T. 2006. Students' attitudes and intentions toward entrepreneurship at Tallinn University of Technology, TUTWPE, (154):97-114. [ Links ]

WICKHAM, P.A. 2006. Strategic entrepreneurship (4th ed.). Harlow: FT Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

WILNER, J. 2009. Characteristics of a successful entrepreneur. Available at: http://entrepreneurs.suite101.com/article.cfm/characteristics_of_a_successful_entrepreneurLinks ] Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif" size="2"> [accessed 2010-07-26].

Accepted: July 2012