Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versión On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.15 no.2 Pretoria ene. 2012

ARTICLES

Financial liberalisation and the dynamics of firm leverage in a transitional economy: evidence from South Africa

Chimwemwe ChipetaI; Hendrik P WolmaransII; Frans NS VermaakII

ISchool of Economic and Business Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

IIDepartment of Financial Management, University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the dynamics of corporate capital structures for listed non-financial firms in South Africa. The dynamic models of capital structure have been utilised to document several findings of empirical significance. First, transaction costs reduce dramatically in the post liberalisation regime, and the associated speed of adjustment is more pronounced, and statistically significant for the post liberalisation epoch. Second, financial liberalisation has a significant impact on the capital structure speed of adjustment. Third, the results confirm most of the theoretical predictions of capital structure theories; however, the relationship is more significant in the post liberalised regime. Finally, new evidence has been revealed on what determines the debt maturity structure of firms in a transitional economy.

Key words: financial liberalisation, leverage, GMM

JEL: G32

1 Introduction

The effect of relaxing the Modigliani and Miller (1958) capital structure irrelevance assumption of perfect capital markets suggests that there are firm-specific impediments that constrain firms from achieving the desired level of the target leverage. Such imperfections include taxes, flotation costs, adjustment costs and other constraints. In the context of financial liberalisation, a constrained economy is one which is characterised by an underdeveloped financial system with relatively fewer financing options. Consequently, firms operating in such an environment may face high transaction costs. Inevitably, firms operating in this environment will adjust to the optimal target with a relatively low speed of adjustment. Conversely, firms operating in a liberalised economy should face fewer impediments in their efforts to adjust to a target level of leverage. The presence of an active and developed stock market, the re- emergence of international financial institutions and an active public debt market promote competition in the domestic financial sector, thereby lowering borrowing costs. Furthermore, Demirguc-Kunt and Maksimovic (1996) argue that the development of the stock market improves transparency and the credibility of listed firms, thereby providing creditors the incentive to advance more debt to listed firms. In effect, the speed of adjustment to the desired target level of leverage should be higher.

Having said this, the issues to be investigated relate to whether firms operating in the period prior to and after financial liberalisation follow a long-run target adjustment to the desired levels of leverage. Pursuant to this, the absence or presence of transaction costs needs to be established. Furthermore, if transaction costs are present, the associated speed of adjustment to the desired level of leverage needs to be ascertained. In addition, very little literature has documented the determinants of financial structure in a closed economy (see Boyle & Eckhold, 1997; Mutenheri & Green, 2003), and how these determinants evolve with the transition to a more liberalised financial environment.

This paper examines these issues for a panel of 70 non-financial firms listed on the Johannesburg Securities Exchange (JSE) for the period between 1989 and 2007. In order to establish the dynamics of firm capital structure in two dramatically different regimes, the Arellano and Bond (1991) and Blundell and Bond (1998) two-step Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) techniques are utilised, and some interesting facts are revealed. First, transaction costs are documented for both the pre and post liberalisation regime. However, it appears that transaction costs reduce dramatically in the post liberalisation regime. The magnitude of the associated coefficient of adjustment increases accordingly. Second, both episodes of financial liberalisation have a significant impact on the speed of adjustment towards the target leverage. Third, the empirical relationship between firm-specific determinants and leverage in a closed economy appears to be weaker than that in the post liberalised regime. Fourth, the results confirm most of the theoretical predictions of capital structure theories. Fifth, new evidence has been documented on what determines the debt maturity structure of firms in a dynamic capital structure setting.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: Section two discusses the factors that are correlated with firm leverage. Section three discusses the relationship between financial liberalisation and firm-financing choices. Section four discusses the data and its sources. Section five estimates the dynamic model of capital structure. Section six discusses the results, and Section seven concludes the paper.

2 Firm-specific determinants of capital structure

2.1 Size

Size can be considered as an explanatory predictor for variations in firm leverage. Larger firms are more likely to take on more debt than smaller firms. Eriotis, Vasiliou and Ventoura-Neokosmidi (2007) argue, firstly, that larger firms can negotiate for loans on more favourable terms. This provides an incentive for them to accumulate more debt at lower interest rates. Secondly, because larger firms are less risky than smaller firms, banks are willing to loan them more funds. This lowers their probability of default. Hence, a positive association is likely to be observed between size and leverage. On the contrary, Drobetz and Wanzenreid (2006) argue that large firms have sufficient analyst coverage and are subject to lower costs of information asymmetries. Hence, they should access equity markets with relative ease. Moreover, the fixed costs associated with equity issues should be smaller for large firms. On that account, size should be inversely correlated to leverage.

The empirical evidence regarding size as a possible determinant of firm leverage is mixed. Marsh (1982) examines the debt-equity choice for firms in the United Kingdom and reports a positive relationship between the size of the firm and leverage. This direct relationship is later confirmed by Bennet and Donnelly (1993). Booth, Aivazian, Demirguc-kunt, and Maksomovic (2001) use the natural logarithm of sales to measure the importance of size in a sample of emerging-market economies, and they find size to be positively correlated with leverage for most of the firms in their sample. On the other hand, Deesomsak, Paudyal and Pescetto (2004) use the natural logarithm of total assets, and they find a strong and statistically significant positive relationship between size and the debt-to-capital ratio for firms in the Asia-pacific region.

Huang and Song (2006) use the natural logarithm of sales as a proxy for size for Chinese firms and they report strong and significant positive correlations between size and total leverage. Similarly, Eriotis et al. (2007) use the natural logarithm of sales and they confirm a statistically significant positive correlation between size and leverage for Greek firms. Alternatively, Gwatidzo and Ojah (2009) use the logarithm of total assets as a proxy for size. They confirm a statistically significant positive relationship between leverage and size for firms in South Africa and Zimbabwe.1

Rajan and Zingales (1995) examine a cross-section of firms in seven industrialised economies and find that size is negatively related to leverage for firms in Germany and France. The plausible explanation for this inverse association is based on information asymmetries. According to the pecking order hypothesis, the information asymmetry between large firms and the capital markets should be low, thus enabling larger firms to issue informational sensitive securities such as equity with ease. This tends to lower the debt levels relative to equity.

Chen (2004) uses the natural logarithm of total assets and documents a negative association between size and the long term debt ratio for Chinese firms. The author argues that the negative association may be due to larger firms' reputation that enables them to access the equity markets with relative ease, and the fact that the Chinese public bond market is virtually non-existent. Delcoure (2007) documents a similar inverse relation between size, measured by the natural logarithm of total assets, and long term leverage for firms in European transition economies. Nunkoo and Boateng (2010) use the GMM technique to estimate capital structure determinants for 835 Canadian firms. They also document a negative correlation between size, measured by the natural logarithm of total sales, and the long term debt ratio.

To summarise, the picture that is emerging is that irrespective of the proxy being used, size tends to be strongly and positively correlated with leverage. However, in some studies, long term leverage is found to be inversely related to the size variable. This is due to the low information asymmetries associated with large firms.

2.2 Profitability

Myers and Majluf (1984) predict that a negative relationship should exist between firm profitability and leverage. They contend that firms that are more profitable will prefer to use retained earnings, and thus will have lower debt ratios. However, the trade-off theory posits that, in order to take advantage of the interest tax shields associated with higher leverage, more profitable firms will have higher debt ratios. Similarly, the free cash flow theory hypothesises that profitable firms should issue more debt. This is a measure to bond the future cash flows and to discipline managers by paying out cash to bondholders instead of wasting the funds on negative NPV projects. The pecking order theory hypothesises that profitability is inversely related to leverage. In contrast, the trade-off and the free cash flow theories suggest that profitability is directly related to leverage.

A number of researchers have tested the effect of profitability on firm leverage. Kester (1986) compares capital and ownership structure of manufacturing firms in the United States and Japan. The author finds that there is a negative relationship between profitability and leverage, measured in terms of the total debt-to-book and market value of equity. Raj an and Zingales (1995) and Wald (1999) draw similar conclusions for the United States, United Kingdom and Japan.

Booth et al. (2001) find a negative correlation between leverage and profitability for a sample of firms in emerging markets. This relationship is, however, stronger than the Rajan and Zingales (1995) observation. Mutenheri and Green (2003) find no significant relationship between leverage and profitability for firms in Zimbabwe. In fact, the observed coefficients for the fixed and random effects models are positive. Bauer (2004) uses restricted OLS models to test the effect of profitability on leverage for Czech firms, and finds a negative and significant association between profitability and the debt ratio. Delcoure (2007) uncovers statistically strong and negative correlations between profitability, measured as the return on total assets, and all measures of leverage. Chang, Lee and Lee (2009) utilise the structural equation model to test the determinants of capital structure for firms in the Compusat industrial files. They confirm a significant negative association between profitability (measured by the ratio of operating income to total assets) and all measures of leverage.

Strebulaev (2007) utilises dynamic trade-off models with adjustment costs and also shows that profitability is inversely related to book and market measures of leverage. Likewise, Gwatidzo and Ojah (2009) find a negative and significant relationship for firms in South Africa and Ghana. The relationship for firms in Zimbabwe is only negative and significant for the short term debt ratio. The only exception is Nigeria where the coefficients are positive and significant for the total and long term debt ratio. This positive association confirms the trade-off and free cash flow theories of capital structure.

The evidence presented in the preceding discussion suggests that most firms in both developed and developing countries follow a pecking order in their financing decisions. These findings confirm the predictions of Myers and Majluf (1984).

2.3 Asset tangibility

The general consensus among researchers is that asset tangibility is directly related to leverage. Jensen and Meckling (1976) point out the possibility of risk shifting strategies whereby managers may shift to riskier investments at the expense of the bondholders. These agency costs of debt can be mitigated if the collateral value of assets is high. Hence, asset tangibility is likely to be positively associated with leverage. Furthermore, in the event of bankruptcy, a higher proportion of tangible assets could enhance the salvage value of the firm's assets. The lenders of finance are thus willing to advance loans to firms with a high proportion of tangible assets.

Harris and Raviv (1991) observe that non-debt tax shields and firm assets are usually regarded as proxies for asset tangibility. Bradley, Jarrell and Kim (1984) use non-debt tax shields as a proxy for asset tangibility, and they find a statistically significant positive relationship between firm leverage and non-debt tax shields. Alternatively, Friend and Lang (1988) use the ratio of net property, plant and equipment to total assets and they report a strong positive relationship between leverage and asset tangibility for both closely held and public corporations. On the other hand, Titman and Wessels (1988) incorporate the ratio of inventory plus gross plant and equipment to total assets and they confirm a positive association between collateral value and leverage.

Rajan and Zingales (1995) use both the book and market values of leverage and they report a positive and significant relationship between leverage and asset tangibility for firms in most of their sampled countries.2

Booth et al. (2001) observe a similar relationship for a sample of emerging market economies. In contrast, Mutenheri and Green (2003) examine the determinants of capital structure for firms in Zimbabwe. They observe a strong negative association between asset tangibility and leverage for the pre reform period (1986-1990). However, a strong positive association is detected for the post reform period (1995-1999).3 The negative association observed for the pre reform period could be associated with the lack of proper contract enforcement systems associated with underdeveloped capital markets. Therefore, asset tangibility may not be used actively as a criterion for advancing loans.

Abor and Biekpe (2005) report a negative and significant relationship between asset tangibility and leverage for Ghanaian firms. They attribute this observation to the higher operating risk associated with a higher proportion of fixed assets. Huang and Song (2006) perform robustness analyses by examining, inter alia, first difference regressions for Chinese firms and a strong positive correlation is observed between asset tangibility and leverage. Gwatidzo and Ojah (2009) use fixed and random effects models and confirm a statistically significant positive relationship for firms in Nigeria and South Africa4 suggesting that financiers in these countries require collateral to issue long term debt. Contrary to the predictions of the theory, Sheikh and Wang (2011: 127) document a strong negative correlation between book leverage and asset tangibility for listed manufacturing firms in Pakistan. The authors note that the negative association could be due to the tendency for managers to 'empire build' at the expense of collateralised assets.

Overall, the empirical evidence discussed so far provides strong support for the positive association between asset tangibility and leverage predicted by capital structure theorists. A negative association is observed only in exceptional circumstances.

2.4 Growth prospects

Capital structure theories suggest that growth opportunities are correlated to firm-financing behaviour. The general consensus among researchers is that growth opportunities are negatively related to leverage, principally because future growth prospects are intangible and hence cannot be easily collateralised (Barclay & Smith, 2005). However, the effect of growth is dependent on the measure used to capture growth. Gupta (1969) uses the annual compounded growth rate in sales and finds that growth firms tend to have higher leverage than non-growth firms. This is partly due to their ability to access external finance in a relatively unconstrained manner.

Titman and Wessels (1988) use the percentage change in total assets and they arrive at a similar conclusion for the ratio of long term debt to the book value of equity. This evidence is consistent with the prediction that growth firms add value to the firm and hence increase the firm's debt capacity. Delcoure (2007) pools data for firms in western European transition economies and fails to find a statistically significant association between firm growth prospects and leverage.

A contrary view is pointed out by Myers (1977) who argues that firms with growth potential will tend to have lower leverage. This is because firms with intangible growth prospects will generally avoid debt to mitigate the potential underinvestment problem associated with financial distress. Eriotis et al. (2007) concur with this viewpoint by positing that growth causes variations in the value of the firm. Larger variations are therefore interpreted as high risk. This presents a significant hurdle for growth firms to raise capital with more favourable terms. Rajan and Zingales (1995) use the market-to-book ratio of total assets to proxy growth opportunities and they find evidence supporting Myers' (1977) prediction. Barclay and Smith (1999) and Ngugi (2008) reach the same conclusion for a sample of 6700 firms covered by Compustat and Kenyan firms respectively. On the contrary, Al Najjar (2011) finds a positive relationship between leverage and growth opportunities (measured by the market-to-book ratio) for Jordanian firms. This finding is contrary to the predictions of Myers (1977) suggesting that growth firms in Jordan prefer to finance investments with debt.

The preceding evidence shows that most studies that use the growth rate of assets as a proxy for firm growth opportunities tend to exhibit strong positive correlations. On the other hand, most studies that use some form of a market-to-book value of assets ratio reveal negative associations between growth and leverage. This is because growth in the asset base of a company provides an incentive for creditors to advance loans to growth firms. Conversely, the market-to-book ratio reveals intangible growth opportunities which may not easily be collateralised.

2.5 Corporate taxes

The introduction of taxes to the Modigliani and Miller (1958) irrelevance model suggests that corporate taxes are a vital element in the determination of firm leverage. Modigliani and Miller (1963) demonstrate that the tax savings associated with interest tax shields induce firms to take on more debt. Therefore, a positive association between tax and leverage should be observed. The bone of contention, however, has been to determine a reliable proxy for the tax rate. Most studies use the ratio of taxes paid to total taxable income, and the empirical evidence has, at most, been conflicting.

Homaifar, Zietz and Benkato (1994) utilise a general autoregressive distributed lag model to test Modigliani and Miller's (1963) tax relevance predictions for both the short run and the long run. They document a long-run positive relationship between leverage and corporate tax. However, no significant relationship is observed in the short run. Graham (2001) uses a sophisticated simulation technique in an attempt to derive a more accurate measure of the effective tax rate and concludes that taxes affect leverage in a positive manner.

Negash (2002) argues that, where there is a change in the tax regime, the use of simulation to estimate the effective tax rate may not be appropriate. In his study of firms operating in a tax regime where firms are not progressively taxed, he finds that taxes are negatively associated with leverage. This finding is confirmed by Abor and Biekpe (2005) for Ghana. However, Ngugi (2008) and Gwatidzo and Ojah (2009) find insignificant correlations for Kenya and South Africa respectively. Likewise, Frank and Goyal (2009) confirm strong negative correlations for the book value measures of leverage. However, strong positive associations are observed for the market value leverage ratios.

In summary, it appears that attempts to determine the effect of tax on leverage have yielded inconclusive results. While Modigliani and Miller's (1963) prediction is confirmed by some studies, the negative association depicted in other studies cannot be ignored. It is therefore necessary to review the corporate tax debate in the context of non-debt tax shields.

2.6 Non-debt tax shields

The presence of non-debt tax shields such as depreciation, operating losses carried forward and investment tax credits in a firm's financial statements reduces the firm's tax bill, thereby lowering the effective tax rate. Recall that Figure 1 shows that the effective tax rates in South Africa have been lower than the statutory rates. This observation can partly be explained by the use of non-debt tax shields in the South African corporate sector.

DeAngelo and Masulis (1980) have illustrated that the tax advantages of debt are lower for those firms with opportunities to avoid tax through other related non-debt tax shelters such as depreciation, investment tax credits and tax loss carry forwards. It follows that firms with higher non-debt tax shields are less likely to issue more debt. Therefore, an inverse relationship is expected between non-debt tax shields and leverage.

Again, the empirical evidence regarding non-debt tax shields has yielded mixed results. For example, Bennet and Donnelly (1993), Saa-Requejo (1996), Wiwattanakantang (1999), De Miguel and Pindado (2001), Ozkan (2001) and Ngugi (2008) confirm the prediction of DeAngelo and Masulis (1980) that non-debt tax shields are a substitute for debt. However, Bradley et al. (1984), Barclay, Smith and Watts (1995) and Boyle and Eckhold (1997)5 provide evidence suggesting that non-debt tax shields have a positive impact on firm leverage. Chang et al. (2009) confirm a positive association between leverage and non-debt tax shields for Compustat- listed non-financial corporations.

This contradiction is not surprising because of two main reasons provided by Barclay and Smith (2005). Firstly, firms with higher non- debt tax shields have higher proportions of tangible assets in their balance sheet. This provides an increased potential to accumulate more debt. Therefore, non-debt tax shields may not only be a proxy for low taxes, but rather a proxy for low contracting costs associated with debt. Secondly, firms with tax loss carry forwards are often in financial distress. Consequently, the market value of equity for such firms is eroded thereby increasing the debt ratio. It is therefore not clear whether tax loss carry forwards are a reliable proxy for non-debt tax shields.

2.7 Dividend pay-out

Miller and Modigliani (1961) have argued that dividend policy does not affect the value of the firm or the cost of equity. If this is true, then dividend policy is irrelevant. Pursuant to this proposition, several financial theorists have argued otherwise, that dividend policy is relevant. Lintner (1962) and Gordon (1963) have argued that investors value the next dollar of dividends more than future capital gains. In effect, the perceived riskiness of a dividend paying firm should be lower than that of a non-dividend payer. Consequently, the required return of a dividend paying firm reduces with an increase in dividends. This proposition has been termed the 'bird-in-hand theory'. On the other hand, the introduction of market imperfections such as taxes into this debate could sway the argument to the other side. Boyle and Eckhold (1997) reason that if capital gains are taxed lower than dividend income, then an increase in dividends will reduce the after-tax return of shareholders who may in turn require a higher pre-tax expected rate of return. Consequently, the increased cost of equity may induce firms to issue more debt relative to equity. In this case, dividend payout may be positively correlated with leverage.

From a South African perspective, inspection of Figure 1 suggests two schools of thought. First, large dividend payments reduce firms' free cash flows thereby reducing funds available for investment projects. This forces corporate managers to seek additional finance from the capital markets. This conjecture is consistent with Jensen's (1986) free cash flow hypothesis discussed earlier.

Second, many listed firms use dividends as a credible signal that their future earnings prospects are sound. This gives them the incentive to seek further borrowing from the capital markets. An inspection of Figure 1 shows that there was an increase in the payouts in the year 1998. This spike in dividend pay-outs is followed by a general rise in the debt ratios in the following two years. Similarly, for the 1991 to 1997 period, it can be noted that declining dividend pay-outs are associated with lower debt ratios. From this viewpoint, South African dividend policy may be positively associated with leverage.

The literature documented in the preceding discussion suggests a strong support for the dividend signalling hypothesis which is consistent with the "bird-in-hand" theory. This empirical evidence suggests that dividend policy does matter. If this is the case, dividend changes may be negatively correlated with leverage. However, the South African perspective suggests that dividend pay-out may be positively associated with leverage.

3 Financial liberalisation and capital structure

The primary motivation for financial liberalisation is documented by Bhaduri (2000) who argues that structural adjustments within the financial sector and the widening and deepening of capital markets have presented firms in developing countries an opportunity to optimally determine their choice of capital structure. Moreover, Prasad, Green and Murinde (2001:22) observe that 'each country's system of corporate finance retains some of its own distinctive features, partly because of its historical development, and partly because of current economic circumstances, particularly the existing regulatory regime'.

These arguments concur with the economic developments in South Africa. For example, the lifting of international sanctions by the end of 1992, and the official liberalisation of the JSE in March 1995 are clear examples of how these events could have impacted in firms' financial choices. Furthermore, Schmukler and Vesperoni (2001) argue that globalisation of the financial markets develops the financial system and improves transparency, market discipline and financial infrastructure. This creates new investment and financing opportunities for domestic firms. For example, Flavin and O'Connor (2010) explore the effects of stock market liberalisation on firms' financial structure in 31 emerging markets, including South Africa. They conclude that stock market liberalisation lowers the debt-to-equity ratio. These arguments suggest that the choice of financial structure is clearly affected by financial liberalisation.

4 Data

The sample consists of non-financial firms that were listed on the JSE before and after the financial liberalisation phase. The I-Net Bridge database is used to source audited income statements, balance sheets and financial ratios for a sample of firms that operated from 1989 to 2007. The data is split between the two regimes, that is the pre liberalisation period (1989-1994), and the post liberalisation period (1995-2007). There is reason enough to believe that the determinants and dynamics of capital structure in the pre liberalisation period may differ from the dynamics of leverage in a post liberalised regime. An underdeveloped financial and institutional setting may be characterised by higher transaction costs and market restrictions such as capital controls and economic sanctions. These impediments should have implications for capital financing decisions by domestic firms (See Boyle & Eckhold, 1997; Mutenheri & Green, 2003).

Table 1 reports the correlation coefficients on the variables used in the analysis. The correlations are not large enough to suggest that there may be a problem of multicollinearity. Furthermore, most of the correlations presented in this table are confirming the predictions of some of the capital structure theories. Growth is negatively correlated to leverage, a confirmation of the contracting cost theory. This relationship is statistically significant for the market value debt ratios. The tangibility variable is positive and significant at the 1 per cent level of significance for all the dependent variables. This shows that asset structure is an important criterion for assessing the firm's ability to access loans. The non-debt tax shield variable is positive and significant at the 1 per cent level for all the dependent variables. The correlation coefficient for the non-debt tax shield and tangibility variables is positive and significant, signifying that firms with high non-debt tax shields have a high proportion of fixed assets. This may provide an incentive for firms to accumulate more debt.

The profitability variable is negatively related to leverage. This negative relationship confirms the pecking order hypothesis. The size variable is positively correlated to the book value measures of leverage, indicating that larger firms have more debt in their capital structure. However, a negative association is observed between size and the market values of leverage, suggesting low information asymmetries associated with large firms. Taxes and dividend pay-out are both negatively related to leverage. The correlations are significant at the 1 per cent level. The next step is to examine these relationships while controlling for other factors.

5 Methodology

5.1 Model specification

The proposed model can be estimated using the following general specification:

where,  is the target leverage for firm i at time t.αi is the unobservable firm-specific effect, and

is the target leverage for firm i at time t.αi is the unobservable firm-specific effect, and  is a vector of lagged characteristics of firm i, including timespecific dummies. In equation 2, μi,t is the vector of unobserved disturbances, where αi is the unobservable firm- specific effect that varies across firms but is fixed over time. vt is the firm invariant time specific effect. εi,t is the white noise disturbance.

is a vector of lagged characteristics of firm i, including timespecific dummies. In equation 2, μi,t is the vector of unobserved disturbances, where αi is the unobservable firm- specific effect that varies across firms but is fixed over time. vt is the firm invariant time specific effect. εi,t is the white noise disturbance.

Bearing in mind that the presence of transaction costs presents an impediment for firms to automatically adjust their capital structure to the desired level, the following partial adjustment model is specified:

The parameter δ is the speed of adjustment. Levi,t - Levi,t-1 is the actual change in leverage and  is the desired change in leverage. If transaction costs are zero, then δ =1, meaning that firms will automatically adjust to their target capital structure. If transaction costs are 1, then δ = 0, meaning that transaction costs are so high that Levi,t = Levi,t-1. From equation 3, the actual leverage level can be computed as:

is the desired change in leverage. If transaction costs are zero, then δ =1, meaning that firms will automatically adjust to their target capital structure. If transaction costs are 1, then δ = 0, meaning that transaction costs are so high that Levi,t = Levi,t-1. From equation 3, the actual leverage level can be computed as:

Substituting equation 3 into equation 1 gives the following specification:

where 1 - δ is a measure of the transaction costs. The presence of the lagged dependent variable on the right hand side of the equation provides a statistical bias where Levi,t-1 will be correlated with the error term, even if μi,t are not serially correlated. This renders OLS estimators to be inefficient. One way to resolve this problem is to first difference equation 5 in order to eliminate the firm-specific effects. OLS may not consistently estimate the parameters (Levi,t-1 Levi,t-2) and (μi,t-1 - μit-2) are correlated through Levi,t-1 and μit-1. This problem can be resolved by utilising an instrumental variable, on condition that the error term μi,t is not serially correlated.

Anderson and Hsiao (1982) recommend [6Levi,t-2 = Levi,t-2 - Levi,t-3 or Levi,t-2 as instruments for the first difference. The instrumental variable estimation technique may not be efficient due to lack of utilisation of all available moments. Arellano and Bond (1991) resolve this by using the GMM estimation technique. The GMM estimation utilises instruments that can be obtained from the orthogonality conditions that exist between the lagged dependent variable and the disturbance term. Robustness checks are performed by estimating equation 5 simultaneously with its differenced form as a 'system'. Hence, this approach is known as System GMM. As noted by Blundell and Bond, (1998), this simultaneous approach to estimating the dynamic regression models provides significant efficiency gains.

The Wald test of joint significance for all regressions is satisfied at the 1 per cent level of significance. The Wald test for the significance of the time effects is significant for all post liberalisation results. The time-specific effects for the pre liberalisation period are mostly insignificant. The significance of the time dummies for the post liberalisation period suggests that aggregate factors have a significant influence on firm-financing behaviour.

The Sargan test of overidentifying restrictions is valid for all regressions. The tests for first-order serial correlation are not satisfied for the total debt ratio regressions and the short term debt ratio model. This is expected because according to Ozkan (2001) transformation induces first order serial correlation in the first differenced residuals. The GMM estimators are consistent based on the assumption that E (μi,t, μi,t-2) are uncorrelated, hence second order serial correlation should not be present. Second order correlation is absent in all the reported results.

5.2 Mean reversion

Kayhan and Titman (2007) and Chang and Dasgupta (2009) argue that the limiting of debt ratios between 0 and 1 could lead to mechanical mean reversion. This could bias the coefficient estimates of the measure of transaction costs. To control for mean reversion, a two-step regression process is followed by estimating the target leverage (equation 1) in the first step using historical fixed effects. In the second step, the target leverage variable is included among the independent variables as shown in equation 6:

Following Hovakimian and Li (2011), mean reversion is controlled by including the coefficient of the lagged dependent variable on the right hand side of the equation, and eliminating extreme leverage observations beyond 0.8. This modified partial adjustment procedure reduces the upward bias in the estimated coefficient of the speed of adjustment.

5.3 The impact of financial liberalisation on the speed of adjustment

In order to estimate the effect of financial liberalisation on the speed of adjustment, two separate dummies are constructed. FINLIB1t captures the effect of the first wave of financial liberalisation that occurred after the lifting of most economic sanctions in 1992. FINLIB2t captures the effect of the second wave of financial liberalisation that occurred after 1995. The coefficient on the interaction term between the target leverage,  and a financial liberalisation dummy, FINLIB1t and FINLIB2t, as shown in equation 7, provides an indication of the impact of the financial reforms on the speed of adjustment:

and a financial liberalisation dummy, FINLIB1t and FINLIB2t, as shown in equation 7, provides an indication of the impact of the financial reforms on the speed of adjustment:

5.4 Industry effects

The extant literature advocates for the effects of industry characteristics on the choice of capital structure. For example, Harris and Raviv (1991) posit that firms in an industry tend to retain their leverage rankings over time. Furthermore, Miao (2005) and Antoniou, Guney and Paudyal (2008) allude to the relevance of the impact of industry effects on firm-financing decisions. It is further argued that firms operating in capital intensive industries such as manufacturing and mining firms should have higher leverage than firms characterised by intangible growth opportunities. For instance, Long and Malitz (1985) show that highly levered firms are asset intensive and mature. Therefore, to control for industry effects, a dummy that takes the value of 1 is used for manufacturing and mining firms and 0 otherwise.

5.5 Model specification tests

The Wald test of joint significance for all regressions is satisfied at the 1 per cent level of significance. The Wald test for the significance of the time effects is significant for all post liberalisation results. The time-specific effects for the pre liberalisation period are mostly insignificant. The significance of the time dummies for the post liberalisation period suggests that aggregate factors have a significant influence on firm-financing behaviour.

The Sargan test of overidentifying restrictions is valid for all regressions. Furthermore, the tests for first order serial correlation are not satisfied for the total debt ratio regressions and the short term debt ratio model. This is expected because according to Ozkan (2001) transformation induces first order serial correlation in the first differenced residuals. The GMM estimators are consistent based on the assumption that E (μi,t, μi,t-2) are uncorrelated, hence second order serial correlation should not be present. Second order correlation is absent in all the reported results.

6 Discussion of results

This section reports the results of the dynamic models elaborated in the preceding discussion.

6.1 The book value of the total debt ratio (Pre liberalisation)

The results for the determinants of capital structure in the pre liberalisation period are reported in Table 2 and discussed in this section. The growth variable is positively correlated to the book value of the total debt ratio. This relationship suggests that high growth firms operating in the pre liberalised regime accumulated more debt to finance their growth prospects. Al Najjar (2011) uses the same proxy for growth as the one used in this paper and finds a similar correlation for Jordanian firms. The expected sign on the tax variable is positive and statistically significant at the 1 per cent level. This result confirms the prediction by Modigliani and Miller (1963) that the tax savings associated with interest tax shields induce firms to take on more debt. The coefficient on the target leverage variable is positive and significant, suggesting that the speed of adjustment in the pre liberalisation period is statistically significant.

6.2 The book value of the total debt ratio (Post liberalisation)

The results for the determinants of the book value of the total debt ratio in the post liberalisation period are reported in Table 2 and discussed in this section. In contrast to the pre liberalisation epoch, firm growth prospects are negatively related to the book value of the total debt ratio. From this outcome, it can be concluded that growth firms in the post liberalisation era avoid debt to mitigate the potential underinvestment problem associated with financial distress. This observation confirms the prediction of Myers (1977) and confirms the findings of Rajan and Zingales (1995), Barclay and Smith (1999) and Ngugi (2008).

In contrast to the literature, the asset tangibility variable is negatively related to leverage and the associated coefficient is significant at the 1 per cent level. This result could be attributed to at least two reasons identified in the literature. Abor and Biekpe (2005) document a similar relationship for firms in Ghana, and they argue that it could be due to the high operating risk associated with a higher proportion of fixed assets. Similarly, Sheikh and Wang (2011:127) document a strong negative correlation between book leverage and asset tangibility for listed manufacturing firms in Pakistan, and they note that the negative association could be due to the tendency for managers to 'empire build' at the expense of collateralised assets. The other plausible explanation to this observation is that firms with high values of tangible assets are associated with high levels of debt (Long & Malitz, 1985). Therefore, any further increases of debt could increase the costs of debt, and the potential costs of financial distress. If this is the case, highly levered, asset intensive firms could find it cheaper to rebalance their capital structure by issuing equity.

The profitability variable is positively correlated to the book values of the total debt ratio. The associated p-value is 0.001. The positive association reported here confirms the prediction of the trade-off theory that profitable firms will borrow more in order to take advantage of the interest tax shields.

The size coefficient is negatively correlated to the book value measure of the total debt ratio. This observed relationship suggests that the information asymmetry between large firms and the capital markets in the post liberalisation epoch is low, thus enabling larger firms to issue informationally sensitive securities such as equity with ease. This tends to lower the debt levels relative to equity. These results corroborate favourably with Chen (2004), Delcoure (2007) and Nunkoo and Boateng (2010).

The expected sign for the tax coefficient is negative and significant at the 10 per cent level. The evidence documented here suggests that taxes play a mildly significant role in the determination of leverage. The negative association observed in the post liberalisation regime confirms the results for Negash (2002) who observes South African firms over a relatively similar period. Given that tax rates in South Africa were on a declining trend, there could have been little incentive for firms to take advantage of the tax deductibility of interest through the accumulation of more debt. Frank and Goyal (2009) draw similar conclusions for the book value measures of total leverage.

The dividend pay-out variable is positively correlated to the book value of the total debt ratio. The correlation coefficient is statistically significant at the 1 per cent level. This positive association is consistent with two schools of thought; firstly, large dividend payments reduce firms' free cash flows thereby reducing funds available for investment projects. This forces corporate managers to seek additional finance from the capital markets. This conjecture is consistent with Jensen's (1986) free cash flow hypothesis that increases in dividend and debt interest payments reduce the firm's free cash flows. Secondly, many listed firms use dividends as a credible signal that their future earnings prospects are sound. This gives them the incentive to seek further borrowing from the capital markets. Furthermore, Boyle and Eckhold (1997) reason that if capital gains are taxed lower than dividend income, then an increase in dividends will reduce the after-tax return of shareholders, who may in turn require a higher pre-tax expected rate of return. Consequently, the increased cost of equity may induce firms to issue more debt relative to equity.

The coefficient on the target leverage variable is positive and significant, suggesting that the speed of adjustment in the post liberalisation era is statistically significant. Furthermore, the magnitude of the coefficient in the post liberalisation epoch is larger than for the pre liberalisation era.

6.3 The market value of the total debt ratio (pre liberalisation)

As shown in Table 3, the only significant correlations in the pre liberalisation epoch are for the size and target leverage variable. Size is negatively correlated to leverage, again confirming the conjuncture that large firms possess the reputational capital which enables them to issue informational sensitive securities such as equity with ease. The coefficient on the target leverage variable is positive and significant, suggesting that the speed of adjustment in the pre liberalisation era is statistically significant.

6.4 The market value of the total debt ratio (post liberalisation)

In contrast to the book values of leverage, the growth coefficient is positive and significant at all conventional levels. Overall, this direct relationship corroborates the empirical findings of Titman and Wessels (1988) and Delcoure (2007), among others. The positive association suggests that growth firms operating in the post liberalisation period require external funding to finance their future growth prospects.

As alluded to in the earlier discussion on the book value debt ratio, the asset tangibility variable is negatively related to leverage and the associated coefficient is significant at the 1 per cent level. This result could be attributed the high operating risk associated with a higher proportion of fixed assets and the tendency for managers to pursue value-destroying projects at the expense of collateralised assets. Furthermore, firms with high values of tangible assets are associated with high levels of debt (Long & Malitz, 1985). Therefore, any further increases of debt could increase the costs of debt, and the potential costs of financial distress. If this is the case, highly levered, asset intensive firms could find it cheaper to rebalance their capital structure by issuing equity.

The non-debt tax shield coefficient is negative and significant at all conventional levels. This negative effect shows that firms with high depreciation charges have little incentive to access more debt. This relationship supports the DeAngelo and

Masulis (1980) hypothesis that tax advantages of debt are lower for those firms with opportunities to avoid tax through other related non-debt tax shelters. The dynamic panel data models employed by De Miguel and Pindado (2001) and Ozkan (2001) also document the negative association found in this study. However, Bradley et al. (1984), Barclay et al. (1995) and Chang et al. (2009), among others, provide evidence suggesting that non-debt tax shields have a positive impact on firm leverage.

The coefficient on the tax variable is positive and significant at the 1 per cent level. The documented direct relationship is an indication that firms in the post liberalisation regime respond to increased effective tax rates by issuing more debt. The evidence documented here suggests that taxes play a significant role in the determination of leverage. These results confirm the finding by Frank and Goyal (2009) that there is a strong and positive correlation between taxes and the market value of total leverage for non-financial firms in the United States of America. However, Ngugi (2008) and Gwatidzo and Ojah (2009) find insignificant correlations between taxes and leverage for Kenya and South Africa, respectively.

The dividend pay-out variable exerts a positive influence on the market value of the total debt ratio. The coefficient is statistically significant at the 1 per cent level, thus confirming Jensen's (1986) free cash flow theory that increases in dividend and debt interest payments reduce the firm's free cash flows. This forces firms to seek funding from external markets. In this case, an increase in the market value of the debt ratio is observed.

The coefficient on the target leverage variable is positive and significant, suggesting that the speed of adjustment in the post liberalisation era is statistically significant. Furthermore, the significance of the coefficient in the post liberalisation epoch is stronger than for the pre liberalisation era. This observation can be attributed to the lower transaction costs depicted in the post liberalised regime.

6.5 Firm-specific determinants of debt maturity

6.6 Determinants of debt maturity structure in the pre liberalisation regime

The results for the determinants of the debt maturity structure in the pre liberalisation period are reported in Table 4 and discussed in this section.

The System GMM output generates significant results for profitability, size and taxes. The coefficients for profitability and size are negative and statistically significant at the 1 per cent level. Profitability is associated with a longer debt maturity structure. This implies that profitability is a significant criterion for securing longer term finance in the pre liberalisation period. Similarly larger firms have longer debt maturity structures. This indicates that larger firms possess the reputational capital to borrow on a longer term basis. On the other hand, taxes are positively related to the maturity structure of debt. However, the correlation coefficient is mildly significant at the 10 per cent level. This relationship suggests that firms that are subject to higher effective tax rates reduce their maturity structure of debt.

6.7 Determinants of debt maturity structure in the post liberalisation regime

The results for the determinants of the debt maturity structure in the post liberalisation period are reported in Table 4 and discussed in this section.

The coefficients of the growth variable for firms in the post liberalisation regime are all statistically significant at the 1 per cent level. Growth prospects are associated with an increase in the short term debt ratio. This implies that growth firms are associated with shorter debt maturities. The plausible explanation to this observation is that the variability in earnings associated with growth firms makes it difficult for them to access long term debt. Hence debt with shorter maturities is more accessible for these firms. As observed by Barclay and Smith (2005), high growth firms tend to borrow on a short term basis. The rationale given for this observation is that, in the event of financial distress, short term debt allows growth firms to reorganise their debt position easily.

The asset tangibility variable has a negative sign. The coefficient is statistically significant at the 1 per cent level. This inverse relationship is an indication that firms with a high proportion of tangible assets increase the maturity structure of their debt. This relationship lends support to the theory that a high value of tangible assets allows firms to borrow on a longer term basis. In the event of bankruptcy, the tangible assets can easily be collateralised.

The profitability variable is negatively correlated to the short term debt ratio. The coefficient is statistically significant at the 1 per cent level. This negative association indicates that profitable firms operating in the post liberalised regime increase the maturity structure of their debt. This is expected, since higher profits provide credibility for firms to take on longer term debt.

The size variable is positively correlated to the short term debt ratio, suggesting that large firms operating in the post liberalised regime issue debt with shorter debt maturities. This finding contradicts the theoretical predictions that large firms have a lower probability of financial distress, and that they have lower information asymmetries associated with debt issues. This should allow them to borrow on a longer term basis.

The tax variable has a negative coefficient which is statistically significant at the 1 per cent level. Hence, it can be deduced that corporate tax rates are negatively associated with short term debt. This finding suggests that an increase in the effective tax rate is associated with longer debt maturities. This result supports the tax clientele argument of Newberry and Novak (1999) that firms that are subject to high effective tax rates will increase their debt maturity structure. The results reported here support the empirical work by Antoniou, Guney and Paudyal (2006). They observe that the increase in the effective tax rate causes a statistically significant increase in the maturity structure of debt for firms in Germany. Furthermore, higher effective taxes could be associated with higher profitability.6 Hence, the negative sign is not surprising. Due to the increased profitability, firms that pay higher taxes will have easier access to longer term financing than firms with lower effective taxes.

The dividend pay-out ratio is positively correlated with the short term debt ratio. The coefficient is significant at the 1 per cent level. The positive correlation suggests that an increase in the dividend pay-out is associated with a reduction in the debt maturity structure of firms.

6.8 Financial liberalisation, transaction costs and the related speed of adjustment

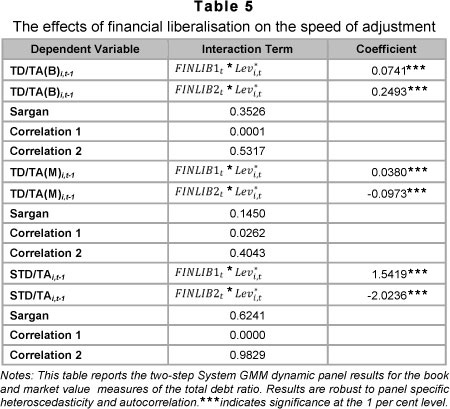

The results of the interaction between the financial liberalisation dummies and target leverage variables are shown in Table 5. The coefficient on the interaction term between FINLIB1t and  , the book value of total target leverage, is positive and significant at all conventional levels. Likewise, the coefficient on the interaction term between FINLIB2t and

, the book value of total target leverage, is positive and significant at all conventional levels. Likewise, the coefficient on the interaction term between FINLIB2t and  , the book value of total target leverage is significantly positive at the 1 per cent level. The coefficients are also significant for the rest of the dependent variables. This outcome confirms that financial liberalisation has a significant impact on the costs of altering capital structure, thereby increasing the speed of adjustment towards the target leverage for the first episode of liberalisation. In the second episode of liberalisation, the speed of adjustment increases again only for the book value of total leverage. The opposite is observed for the market value total leverage and the short term leverage.

, the book value of total target leverage is significantly positive at the 1 per cent level. The coefficients are also significant for the rest of the dependent variables. This outcome confirms that financial liberalisation has a significant impact on the costs of altering capital structure, thereby increasing the speed of adjustment towards the target leverage for the first episode of liberalisation. In the second episode of liberalisation, the speed of adjustment increases again only for the book value of total leverage. The opposite is observed for the market value total leverage and the short term leverage.

7 Conclusions

This paper has examined the empirical association between firm-specific characteristics and capital structure in a transitional economy. The dynamic models of capital structure have revealed several important facts. First, the study documents evidence of a long-run target adjustment to the desired level of leverage. Second, a reduction in transaction costs is observed for the post liberalisation regime. Third, firms in a liberalised economy adjust to their optimal target of leverage much faster than firms in a constrained economy.

The capital structure model has documented relationships that support most of the theories of capital structure. However, the empirical relationship between the firm-specific determinants of capital structure and leverage is statistically stronger for the post liberalised regime than the pre liberalised era. The same holds for the coefficient on the target leverage, thereby confirming the paper's conjecture that transaction costs are lower in a post liberalised regime. Furthermore, two episodes of financial liberalisation have been shown to have a significant impact on the speed of adjustment to the target leverage. Finally, new evidence shows that the debt maturity structure is significantly affected by most of the firm-specific characteristics, especially in the post liberalisation period.

Endnotes

1 The only exception was for Nigeria where there was a significant negative relationship between leverage and size. The coefficients for Kenya were negative but insignificant with the exception of the long term debt ratio.

2 There are two exceptions to this observation; when book values are used, the relationship is positive but insignificant for Italy, and when market values are used, a positive and insignificant association is observed for France.

3 This strong relationship is found using the fixed and random effects models. The pooled least squares approach yields no statistically significant results.

4 The only exception for South Africa is the short term debt ratio, which is significantly negatively related to asset tangibility.

5 Boyle and Eckhold (1997: 434) report a positive correlation for the long term debt ratio for the pre liberalisation period and insignificant positive correlation for the post liberalisation period. The short term debt ratio is positively correlated to leverage for the pre liberalisation period and negatively correlated to leverage for the post liberalisation period.

6 According to Table 1, the correlation coefficient between tax and profitability variable is 0.40 indicating that effective tax rates and profitability are correlated.

References

ABOR, J. & BIEKPE, N. 2005. What determines the capital structure of listed firms in Ghana? African Finance Journal, 7(1):37-48. [ Links ]

AL NAJJAR,B. (2011). Empirical Modelling of Capital Structure: Jordanian Evidence. Journal of Emerging Market Finance, 10(1):1-19. [ Links ]

ANDERSON, T.W. & HSIAO, C. 1982. Formulation and estimation of dynamic models using panel data. Journal of Econometrics, 18(1):47-82. [ Links ]

ANTONIOU, A.Y., GUNEY, Y. & PAUDYAL, K. 2006. The determinants of debt maturity structure, evidence from France, Germany and UK. European Financial Management, 12(2):161-194. [ Links ]

ANTONIOU, A,.Y. GUNEY, Y, & PAUDYAL, K 2008. The determinants of capital structure: capital market-oriented versus bank-oriented institutions. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 43(1):59-92. [ Links ]

ARELLANO, M. & BOND, S. 1991. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58(2):277- 297. [ Links ]

BARCLAY, M.J. & SMITH, C.W. 1999. The capital structure puzzle. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 12(1):8-20. [ Links ]

BARCLAY, M.J. & SMITH, C.W. 2005. The capital structure puzzle: the evidence revisited. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 17(1):8-17. [ Links ]

BARCLAY, M.J., SMITH, C.W. & WATTS, R.L. 1995. The determinants of corporate leverage and dividend policies. Journal of applied corporate finance, 7(4):4-19. [ Links ]

BAUER, P. 2004. Determinants of capital structure: empirical evidence from the Czech Republic. Czech Journal of Economics and Finance, 54 (1): 1-21. [ Links ]

BENNETT, M. & DONNELLY, R. 1993. The determinants of capital structure: some UK evidence. British Accounting Review, 25(1):43-59. [ Links ]

BHADURI, S.N. 2000. Liberalisation and firm's choice of financial structure in an emerging economy: the Indian corporate sector. Development Policy Review, 18(4):413-434. [ Links ]

BOOTH, L., AIVAZIAN, V., DEMIRGUC-KUNT, A. & MAKSOMOVIC, V. 2001. Capital structures in developing countries. The Journal of Finance, 56(1):412-430. [ Links ]

BOYLE, W. & ECKHOLD, K.R. 1997. Capital structure choice and financial market liberalisation: evidence from New Zealand. Applied Financial Economics, 7(4):427-437. [ Links ]

BRADLEY, M., JARRELL, A. & KIM, H. 1984. On the existence of an optimal capital structure: theory and evidence. The Journal of Finance, 39(3):857-878. [ Links ]

BLUNDELL, R.W. & BOND S.R.1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1):115-143. [ Links ]

CHANG, X. & DASGUPTA, S. 2009. Target behaviour and financing: how conclusive is the evidence? The Journal of Finance, 64(4):1767-1796. [ Links ]

CHANG, C., LEE, A.C. & LEE, C.F. 2009. Determinants of capital structure choice: a structural equation modelling approach. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 49(2):197-213. [ Links ]

CHEN, J.J. 2004. Determinants of capital structure of Chinese-listed firms. Journal of Business Research, 57(12):1341-1351. [ Links ]

DEANGELO, H. & MASULIS, R.W. 1980. Optimal capital structure under corporate and personal taxation. Journal of Financial Economics, 8(1):3-29. [ Links ]

DEESOMSAK, R; PAUDYAL, K. & PESCETTO, G. 2004. The determinants of capital structure: Evidence from the Asia Pacific region. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 14(4-5):387-405. [ Links ]

DELCOURE, N. 2007. The determinants of capital structure in transitional economies. International Review of Economics and Finance. 16(3):400-415. [ Links ]

DE MIGUEL, A. & PINDADO, J. 2001. Determinants of capital structure: new evidence from Spanish panel data. Journal of Corporate Finance, 7(1):77-99. [ Links ]

DEMIRGUC-KUNT, A. & MAKSIMOVIC, V. 1996. Stock market development and firm financing choices. World Bank Economic Review, 10(2):341-369. [ Links ]

DROBETZ, W. & WANZENRIED, G. 2006. What determines the speed of adjustment to the target capital structure? Applied Financial Economics, 16(13):941-958. [ Links ]

ERIOTIS, N., VASILIOU, D. & VENTOURA-NEOKOSMIDI, Z. 2007. How firm characteristics affect capital structure: an empirical study. Managerial Finance, 33(5):321-331. [ Links ]

FLAVIN, T. & O'CONNOR, T. 2010. The sequencing of stock market liberalisation dates and corporate financing decisions. Emerging Markets Review, 11(3):183-204. [ Links ]

FRANK, M.Z. & GOYAL, V.K. 2009. Capital structure decisions: which factors are reliably important? Financial Management, 38(1):1-37. [ Links ]

FRIEND, I. & LANG, L.H.P. 1988. An empirical test of the impact of managerial self-interest on corporate capital structure. The Journal of Finance, 43(2):271-281. [ Links ]

GORDON, M.J. 1963. Optimal investment and financing policy. The Journal of Finance, 18(2):264-272. GRAHAM, J. 2001. Estimating the tax benefits of debt. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 14(1):42-54. [ Links ] [ Links ]

GUPTA, M.C. 1969. The effect of size, growth, and industry on the financial structure of manufacturing companies. The Journal of Finance, 24(3):517-529. [ Links ]

GWATIDZO, T. & OJAH, K. 2009. Corporate capital structure determinants: evidence from five African countries. African Finance Journal, 11(1):1-23. [ Links ]

HARRIS, M. & RAVIV, A. 1991. The theory of capital structure, The Journal of Finance, 46(1): 297-355. [ Links ]

HOMAIFAR, G., ZIETZ, J. & BENKATO, O. 1994. An empirical model of capital structure: some new evidence. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 21(1): 1-14. [ Links ]

HOVAKIMIAN, A, & LI, G. 2011. In search for conclusive evidence: how to search for adjustment to target capital structure. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17(1):33-44 [ Links ]

HUANG, G. & SONG, F.M. 2006. The determinants of capital structure: evidence from China. China Economic Review, 17(1):14-36. [ Links ]

JENSEN, M.C. 1986. Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance and takeovers. American Economic Review, 76:323-339. [ Links ]

JENSEN, M.C. & MECKLING, W.H. 1976. Theory of the firm: managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4): 305-360. [ Links ]

KAYHAN, A. & TITMAN, S. 2007. Firms' histories and their capital structures. Journal of Financial Economics, 83(1): 1-32. [ Links ]

KESTER, C. 1986. Capital and ownership structure: a comparison of United States and Japanese manufacturing corporations. Financial Management, 15(1):5-6. [ Links ]

LINTNER, J. 1962. Dividends, earnings, leverage, stock prices, and the supply of capital to corporations. Review of Economics and Statistics, 44(3):243-269. [ Links ]

LONG, M, & MALITZ, I. 1985. The investment-financing nexus: some empirical evidence. Midland Corporate Finance Journal, 3(3). [ Links ]

MARSH, P. 1982. The choice between equity and debt: an empirical study. The Journal of finance, 37(1): 121-144. [ Links ]

MIAO, J. 2005. Optimal capital structure and industry dynamics. The Journal of Finance, 60(6):2621-2659. [ Links ]

MILLER, M.H. & MODIGLIANI, F. 1961. Dividend policy, growth and the valuation of shares. The Journal of Business, 34(4):411-433. [ Links ]

MODIGLIANI, F. & MILLER, M.H. 1958. The cost of capital, corporate finance and the theory of investment. American Economic Review, 48(3):201-297. [ Links ]

MODIGLIANI, F. & MILLER, M.H. 1963. Corporate income tax and the cost of capital: a correction. American Economic Review, 53(3):433-443. [ Links ]

MUTENHERI, E. & GREEN, C.J. 2003. Financial reform and financing decisions of listed companies in Zimbabwe. The Journal of African Business, 4(2):155-170. [ Links ]

MYERS, S. 1977. The determinants of corporate borrowing. Journal of Financial Economics, 5(2):147-176. [ Links ]

MYERS, S. & MAJLUF, N. 1984. Corporate financing and investment decision when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics, 13(2):187-221. [ Links ]

NEGASH, M. 2002. Corporate tax and capital structure: some evidence and implications. Investment Analysts Journal, 56:17-27. [ Links ]

NEWBERRY, K.J. & NOVACK, G.F. 1999. The effects of taxes on corporate debt maturity decisions: an analysis of private and public bond offerings. Journal of American Taxation Association, 21(1):1-16. [ Links ]

NGUGI, R. 2008. Capital financing behaviour: evidence from firms listed on the Nairobi stock exchange. The European Journal of Finance, 14(7):609-624. [ Links ]

NUNKOO, P.K. & BOATENG, A. 2010. The empirical determinants of target capital structure and adjustment to long run target: evidence from Canadian firms. Applied Economics Letters, 17(10):983-990. [ Links ]

OZKAN, A. 2001. Determinants of capital structure and adjustment to long run target: evidence from UK company panel data. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 28(1): 175-198. [ Links ]

PRASAD, S., GREEN, C.J. & MURINDE, V. 2001. Company financing, capital structure and ownership: a survey, and implications for developing economies. Economic Research Paper, 1(3):1-90. Available at: https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/dspace-jspui/bitstream/2134/425/17erp01-3.pdf [accessed 2010-05-26]. [ Links ]

RAJAN, R.G. & ZINGALES, L. 1995. What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. The Journal of Finance, 50(5):1421-1460. [ Links ]

SAA-REQUEJO, J. 1996. Financing decisions: lessons from the Spanish experience. Financial Management, 25(3):44-56 [ Links ]

SCHMUKLER, S. & VESPERONI, E. 2001. Globalisation and firms' financing choices: evidence from emerging economies. World Bank Working Paper, No. 2323. [ Links ]

SHEIKH, N.A. & WANG, Z. 2011. Determinants of capital structure: an empirical study of firms in manufacturing industry of Pakistan. Managerial Finance, 37(2): 117-133. [ Links ]

STREBULAEV, I.A. 2007. Do tests of capital structure theory mean what they say? The Journal of Finance, 62(4):1747-1787. [ Links ]

TITMAN, S. & WESSELS, R. 1988. The determinants of capital structure choice. The Journal of Finance, 43(1):1-19. [ Links ]

WALD, J. 1999. How firm characteristics affect capital structure: an international comparison. The Journal of Financial Research, 22(2):161-187. [ Links ]

WIWATTANAKANTANG, Y. 1999. An empirical study on the determinants of the structure of Thai firms. Pacific Basin Finance Journal, 7(3-4):371-403. [ Links ]

Accepted: April 2012