Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versión On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.15 no.1 Pretoria ene. 2012

ARTICLES

Employee susceptibility to experiencing job insecurity

Leigh-Anne Paul DachapalliI; Sanjana Brijball ParumasurII

IDepartment of Human Resource Management, UNISA

IISchool of Management Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal

ABSTRACT

Employees attach value to their job features/total job and when they perceive threats to these and experience feelings of powerlessness, their level of job insecurity increases. Since job insecurity is a subjective phenomenon, the study aims to assess who is more susceptible to experiencing job insecurity by assessing biographical correlates. The research adopts a formal, hypothesis-testing approach where quantitative data were collected using a cross-sectional, survey method from a sample of 1620 employees. The results, generated using the ANOVA model, indicate that biographical influences do exist in terms of job insecurity. The implication is that change managers need to take cognisance of these influences and develop suitable strategies for each group to reduce the prevalence of job insecurity. Recommendations are made in this regard.

Key words: importance of job features; existence of job features; perceived threats to job features; importance of total job; perceived threats to total job; powerfulness/powerlessness; biographical correlates

JEL: J28, M12

1 Introduction

Working life has been subject to dramatic change over the past decades as a result of economic recessions, new information technology, industrial restructuring and accelerated global competition (Hartley, Jacobson, Klandermans & van Vuuren, 1991; Hellgren, Sverke, & Isaksson, 1999). As a consequence, organisations have been forced to engage in various adaptive strategies in order to tackle new demands and remain vigorous in this unpredictable environment. They have two options to become more profitable; they can either increase their gains or decrease their costs, often by reducing the number of employees (Burke & Cooper, 2000; Tetrick & Quick, 2003). These organisational options often surface in actions like outsourcing and privatisations, often in combination with personnel reductions through layoffs, offers of early retirement and increased utilisation of sub-contracted workers (Burke & Cooper, 2000; Tetrick & Quick, 2003). These changes have impacted tremendously on organisational structures and have created a continuous need for organisational changes in terms of retrenchments, rightsizing, mergers and acquisitions and downsizing. As a result of these changes, job insecurity has emerged as one of the most important issues in working life and has brought the issue of insecure working conditions to the forefront (Sverke, Hellgren & Näswall, 2002).

2 The definition and nature of job insecurity

Job insecurity is situated between employment and unemployment because it refers to employed people who feel threatened by unemployment (Hartley et al, 1991). Job insecurity has been conceptualised from two points of view, that is, as a multi-dimensional concept or as a global concept. In terms of the former, Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt (1984:438) define job insecurity as a "sense of powerlessness to maintain desired continuity in a threatened job situation". In terms of the latter viewpoint, job insecurity signifies the threat of job loss and job discontinuity (De Witte, 1999). Hence, job insecurity is said to be an individual's expectations about continuity in a job situation (Davy, Kinicki & Scheck, 1997); the perception of a potential threat to continuity in his or her current job (Heaney, Israel & House, 1994). This definition has been applied in the context of organisational crisis or change in which job insecurity is considered as a first phase of the process of job loss (Ferrie, 1997). Researchers who adopt a multi-dimensional definition of job insecurity argue that job insecurity refers not only to the degree of uncertainty, but also to the components of job insecurity, namely:

• The severity of the threat concerning job continuity or aspects of the job;

• The importance of the job feature to the individual;

• The perceived threat of the occurrence of a total negative effect on the job situation;

• The total importance of the changes; and

• Powerlessness and inability of the individuals to control the above mentioned factors.

Job insecurity is more than the perceived threat of job loss but also includes thoughts about losing valued job features such as pay, status, opportunity for promotion and access to resources. Very often individuals further characterise the threats to the entire job as more severe than the threats to the job features, because one can lose one's job features but still maintain organisational membership. However, loss of the entire job entails potential job loss or loss of career advancement (Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt, 1984).

Likewise, Hellgren et al. (1999) differentiate between two different forms of job insecurity: quantitative job insecurity, that is, worrying about losing the job itself, and qualitative job insecurity, that is, worrying about losing important job features. Whilst quantitative job insecurity is related to the general, comprehendsive operationalisation of the construct, qualitative job insecurity refers to feelings of potential loss in the quality of the organisational position, such as, worsening of working conditions, lack of career opportunities and decreasing salary development (Sverke & Hellgren, 2002).

The underlying theme behind the various definitions is that job insecurity is a subjective phenomenon, that is, it is based on the individual's perceptions and interpretations of the immediate work environment (Hartley et al., 1991). Job insecurity refers to the anticipation of this stressful event in such a way that the nature and continued existence of one's job are perceived to be at risk, thereby implying that the feeling of job insecurity only occurs in the case of involuntary job loss. Two main themes identified within job insecurity are differentiated by Borg & Elizur (1992) as being:

• Cognitive job insecurity, which refers to the likelihood of job loss.

• Affective job insecurity, which refers to the fear of job loss.

3 The dimensions of job insecurity

In this study it is believed that in order for qualitative job insecurity to take place, individuals must attach importance to the job features and they must regard the existing job features as being salient. Therefore, the dimensions of job insecurity include:

• The importance of job features: This determines the salience of job features such as pay, status, opportunity for promotion, access to resources, career opportunities, and position within the organisation.

• The existence of job features: This determines the extent to which salient job features exist in the organisation.

• Perceived threats to job features: This refers to the estimated likelihood of losing salient job features and feelings that important job features are being threatened.

• Importance of the total job: This determines how salient the total job is to the individual.

• Perceived threats to total job: This refers to the estimated likelihood of one's job itself being at risk or perceptions of losing one's job.

• Feelings of powerfulness/powerlessness: For example, during a process of transformation individuals do not know how to protect themselves and this sense of powerlessness of being unable to secure their futures intensifies the insecurity that they experience.

4 Perceptions of job features

Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt (1984) indicate that job features are as important as the total job, because loss of valued job features represents some aspects of job insecurity, but will be less severe than losing the total job itself. Brun and Milczarek (2007), like Chovwen and Ivensor (2009), find a significant relationship between the existence of job features and perceived threats to job features, such as position within an organisation or career opportunities. This reveals that although the job features do exist, individuals perceive that threats to these job features are a result of the restructuring that is taking place in the organisation.

5 Perceptions of total job

Ugboro and Obeng (2001) find that the relationship between perceived threats to job features and perceived threats to the total job have direct significance. This indicates that as threats to job features increase so do the threats to the total job.

6 The consequences of job insecurity

Since job insecurity involves the experience of a threat, and implies a great deal of uncertainty regarding whether individuals get to keep their jobs in the future, it has been described as a stressor (Barling & Kelloway, 1996; De Witte, 1999; Mauno & Kinnunen, 1999). Like other work-related stressors, job insecurity is associated with a number of detrimental consequences for both the individual and the organisation. The perception of job insecurity is frequently linked to reduced organisational commitment (Borg & Dov, 1992; Forbes, 1985), job satisfaction (Lord & Hartley, 1998), job involvement (Sverke et al., 2002), job performance and productivity (Dunlap, 1994), work effort (Brockner, Grover, Reed & De Witte, 1992), mistrust in management (Ashford, Lee, Bobko, 1989; Forbes, 1985) and intention to leave the organisation (Ashford et al., 1989; Davy et al., 1997; Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt, 1984). Job insecurity is also associated with decreased safety, motivation (Borg & Dov, 1992; Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt, 1984) and compliance, increasing the risks of workplace injuries and accidents (Probst & Brubaker, 2001). Evidently, job insecurity is consistently associated with lower levels of relevant job attitudes and behaviours. Furthermore, job insecurity is also associated with higher levels of burnout, anxiety and depression and psychosomatic complaints (De Witte, 1999; Hartley et al., 1991). Several research studies have suggested that job insecurity should be related to different negative outcomes which may be roughly categorised as attitudinal, health related and behavioural (Ashford et al., 1989; Dekker & Schaufeli, 1995; et al., 1994; Sverke & Hellgren, 2002; Hellgren et al., 1999; Probst, 2003; Sverke et al., 2002). Prolonged job insecurity is more detrimental and acts as a chronic stressor whose negative effects become more potent as time goes by (Dekker & Schaufeli, 1995), thereby emphasising the importance of early identification of its occurrence.

7 The dimensions of job insecurity and biographical data

Evidently, job insecurity is a subjective phenomenon. Hence, the aim of the study is to determine whether specific biographical correlates exist in terms of job insecurity in order to assess which employees, if any, are susceptible to job insecurity.

7.1 Age

Villosio, Di Pierro, Giordanengo, Pasqua and Richiardi (2008) find a significant relationship between age and importance to job features indicating that older workers attach more importance to job features than younger workers. Mohr (2000) finds a strong, direct relationship between age and threats to job features, indicating that older employees experience more threats to job features than younger employees. Sverke, Hellgren and Näswall (2006) find a significant relationship between age and importance of total job, where employees in their 30s and 40s attach more importance to total job because of their family responsibility. Green (2008) and Mauno, Kinnunen, Mäkikangas & Nätti (2005) and Villosio et al. (2008) find that younger workers are likely to feel more insecure than older workers. However, Pedraza and Bustillo (2007) find a significant difference in the level of threat to total job experienced by employees in the different age groups, indicating that younger workers between the ages of 16 and 24 do not fear losing their jobs, because they do not have family responsibilities unlike those who are above 45 years.

7.2 Tenure

According to Bender and Sloane (1999), a strong relationship is found between tenure and the importance that individuals attach to their jobs. Maurin and Postel-Vinay (2005) find that workers on a fixed-term contract attach less importance to their job features than those on permanent contracts. Cheng and Chan (2008) find a significant relationship between tenure and threats to job features. Bender and Sloane (1999), unlike Ugboro (2003), find a strong, direct relationship between tenure and powerlessness.

7.3 Race

Ugboro and Obeng (2001) find that White employees attach less importance to their job features because of the insecurity that they feel whereas their other counterparts attach more importance to job features. However, Burgard, Brand and House (2006) find that Blacks indicated less attachment to their jobs as compared to their non-Black counterparts. Orpen (1993) finds a significant relationship between threats to job features and race indicating that Black employees experience more threats to job features than White employees. Van Wyk and Pienaar (2008) find a significant relationship between perceived threats to total job and race, indicating that White employees experience higher levels of threat to their total job than their Black counterparts. Labuschagne, Bosman and Buitendach (2005), unlike Jorge (2005), find that White employees experience more powerlessness and job insecurity than Black employees.

7.4 Number of years in current position

Ugboro and Ubeng (2001) find that individuals who have spent a number of years in their current position do not attach importance to their job features; however, they do feel powerless. Thus, employees with very short and with very long job tenures in their current position experience a relatively high level of job insecurity and attach less importance to their job features (Erlinghagen, 2007).

7.5 Gender

Male employees experience more insecurity than females and may feel that organisational change will affect the features of their jobs (Ugboro & Obeng, 2001). However, Green (2008) finds that female employees are more insecure than male employees thereby indicating that males are more confident of the existence of the salient features in their jobs. Erlinghagen (2007), on the other hand, finds no gender-specific differences with regard to job insecurity and Burke, Mattiesen, Einarsen, Fiskenbaum and Soiland (2008) reveal no relationship between gender and importance of job features. Ojedokun (2008) reveals that there is a significant difference in the threats perceived by males and females regarding their job features. Likewise, Rosenblatt, Talmud and Ruvio (1999) find a significant difference between the genders and perceived threats to job features, in that, men are more insecure than females because they emphasise financial concerns and family responsibilities whereas women express concerns about their job features, such as, work content and work schedule. Furthermore, Rosenblatt et al. (1999) and Elizur (1994) find a significant difference between gender and importance of total job in that females attach more importance to their jobs than males. However, Mauno and Kinnunen (2002), Bridges (1989) and Tolbert and Moen (1998) indicate that males attach more importance to their jobs than females. Harpaz (1990) and Scozzaro and Subich (1990) find no gender differences in this regard. Whilst Erlinghagen (2007) found no genderspecific differences with regard to threats to total job, Kinnunen, Mauno, Nätti and Happonen (2000) find that women feel more threatened by job insecurity and display higher levels of powerlessness than males in the banking sector whilst the converse is true in the study of Mauno et al. (2005).

7.6 Region

Whilst no results were found for region, results for different countries were noted. Green, Burchell & Felstead (2000) identify Bulgaria, France, Russia and the UK as the countries with the highest levels of job insecurity and Denmark, Norway, the USA and Netherlands as those with the lowest levels. Bustillo and Pedraza (2007) find significant differences in the perceptions of people living in different regions (Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands) towards perceived threats to job features. Probst and Lawler (2006) indicate a significant relationship between countries (China and the US) and the importance of total job and job insecurity respectively indicating that people in the US attach more importance to total job and experience less job insecurity than employees in China.

Undoubtedly, the increasing antecedents and the detrimental consequences (individual and organisational) of job insecurity necessitate the study of the potential biographical correlates so as to attempt to reduce susceptibility to job insecurity in the future.

8 Research design

8.1 Participants

In this study, the target population consists of 8341 employees from a telecommunications company. The population is made up of employees from the Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal provinces. A sample of 1620 employees was drawn from both regions using a probability sampling technique, namely, simple random sampling, whereby subjects were extracted using a random number selection process. According to Sekaran (2003), the corresponding minimum sample size for a population size of 8341 is 367, which confirms that the sample size of 1620 is more than adequate for the study. The adequacy of the sample for conducting Factor Analyses was further determined using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy for the measurement of Job Insecurity (0.914) and Bartlett's Test of Sphericity (66210.340; p = 0.000), which respectively indicated suitability/adequacy and significance. The results indicate that the normality and homoscedasticity preconditions are satisfied.

When categorised on the basis of region, the majority of the respondents (63.8 per cent) were from Gauteng whilst 36.2 per cent were from KwaZulu-Natal. In addition to region, the sample is classified on the basis of biographical data, namely, age, tenure, race, number of years in current position and gender. In terms of age, the highest percentage of respondents (42.1 per cent) fell in the age group of 30-39 years, followed by 40-49 years (36.5 per cent), 50 years and above (12.5 per cent) and 20-29 years (8.8 per cent) respectively. The majority of the respondents are in the age group 30-49 (78.6 per cent). In terms of tenure, 54.5 per cent of the respondents had been working at the company for 16 years or more, 28.1 per cent for between 6 and 10 years, 9.3 per cent for between 0 and 5 years and 8.1 per cent had been serving the organisation for 11 to 15 years. Furthermore, the majority of respondents are Whites (45.1 per cent), followed by Blacks (28.1 per cent), Indians (19.2 per cent) and then Coloureds (7.6 per cent). When distinguished on the basis of number of years in current position, it is evident that 53.8 per cent of the respondents have been in their current position for more than ten years, 23.7 per cent for between 7 and 9 years, 11.9 per cent for between 0 and 3 years and 10.6 per cent for between 4 and 6 years. Furthermore, the sample is comprised of 74.3 per cent male respondents and 25.7 per cent females.

8.2 Measuring instruments

Data was collected using an adapted version of the measuring instrument of Ashford et al. (1989) to assess the level of job insecurity. The questionnaire was comprised of two sections, namely, Section 1 which included biographical data relating to age, tenure, race, number of years in current position, gender and region, which were measured on a nominal scale and Section 2 which assessed the level of job insecurity. Section 2 was comprised of structured questions using closed-ended questions, relating to six sub-dimensions of job insecurity:

• The importance of job features to the individual relating to opportunities for promotion, freedom to schedule one's own work and, current pay (17 items);

• The existence of job features which encompass perceptions of the extent to which the individual believes that the salient job features exist in his/her job (17 items);

• The perceived threats to job features which relate to perceived fear by the individual that his/her job features will be under threat in the process of change (17 items). The greater the extent to which the individual perceives job features to be threatened, the greater the job insecurity;

• The importance of total job in terms of the individual's current job (10 items);

• The perceived threats to total job which encompass the perceived fear by the individual that his/her job will be under threat in the process of change (10 items);

• Powerfulness/powerlessness which encompass an individual's ability/inability to counteract the threats (3 items). Those who are high in powerfulness or low in powerlessness should not experience much job insecurity.

These sub-dimensions were measured on a 1 to 5 point itemised scale ranging from very unimportant (1) to very important (5) and, a 1 to 5 point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

8.3 Research procedure

In-house pretesting was adopted by distributing the designed questionnaire to colleagues and experts in the field to comment on the items, structure and layout of the measuring instrument. In addition, pilot testing was used to detect whether weaknesses in the design and instrumentation of the questionnaire exist, using the same protocols and procedures as those designated for the actual data collection process. Fifteen questionnaires were distributed to various categories of employees that reflected the demographics of those included in the main study. The pilot study confirmed, interalia, the adequacy of the items.

8.4 Statistical analysis

The validity of the questionnaire was statistically analysed using Factor Analysis (Table 1). The Principal Component Analysis was adopted using the Varimax Rotation Method and 6 Factors with latent roots >1 were generated. Only items with loadings >0.5 were regarded as being significant and when an item was significant on two or more factors, only the one with the greatest loading was considered.

Table 1 indicates that sixteen items load significantly on Factor 1 and account for 11.84 per cent of the total variance in determining job insecurity. Since all sixteen items relate to perceived threats to job features, Factor 1 may be labeled likewise. Furthermore, Table 1 indicates that fifteen items load significantly on Factor 2 and account for 9.39 per cent of the total variance in determining job insecurity. Since all fifteen items relate to importance of job features, Factor 2 may be labeled likewise. Table 1 also reflects that fourteen items load significantly on Factor 3 and account for 9.34 per cent of the total variance. Since all fourteen items relate to existence of job features, Factor 3 may be labeled as existence of job features. From Table 1 it can be noted that eight items load significantly on Factor 4 and account for 7.35 per cent of the total variance in determining job insecurity. Since all the items relate to importance of total job, Factor 4 may be labeled likewise. It is evident from Table 1 that eight items load significantly on Factor 5 and account for 6.52 per cent of the total variance. Since all eight items relate to perceived threats to total job, Factor 5 may be labeled likewise. Table 1 reflects that five items load significantly on Factor 6 and account for 4.17 per cent of the total variance in determining job insecurity. Two items relate to perceived threats to total job and three items relate to powerfulness/powerlessness. Since more items relate to powerfulness/powerlessness, Factor 6 may be labeled such since the three items had moderate to high item loadings.

The reliability of the questionnaire was statistically assessed using Cronbach's Coefficient Alpha and indicated a very high level of internal consistency of the items (Alpha = 0.901) with item reliabilities ranging from 0.899 to 0.902 and hence, reflecting a very high degree of reliability. Descriptive statistics (frequency analyses, mean analyses and standard deviations) and inferential statistics (general ANOVA model) were used to analyse the results of the study.

9 Results

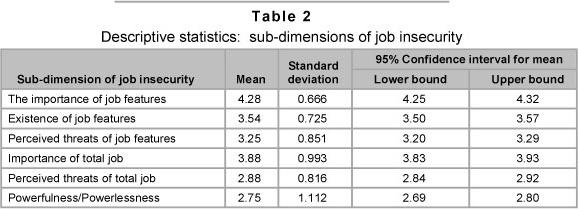

Table 2 indicates the descriptive statistics for each of the sub-dimensions of job insecurity. The greater the mean score value, the greater the extent to which the sub-dimension exists. However, in the powerfulness/powerlessness sub-dimension of job insecurity, the greater the score value, the greater the extent of powerfulness and the less the degree of powerlessness displayed.

Table 2 reflects that employees strongly reflect that job features are very important to them (Mean = 4.28). However, whilst they do believe that these job features do exist in their jobs (Mean = 3.54), it is evident that they perceive a high level of threat to these job features (Mean = 3.25) that are so valued. Likewise, Table 2 reflects that employees believe strongly that their total job is important to them (Mean = 3.88). However, they do perceive that their total job is under threat (Mean = 2.88).

9.1 Hypothesis 1

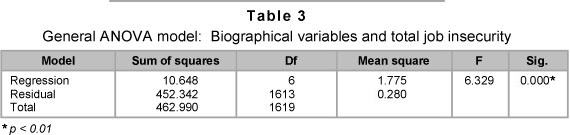

The interactive influences of all the biographical variables (gender, age, tenure, race, number of years in current position, region) result in significant differences in overall job insecurity amongst employees (Table 3).

Table 3 indicates that all of the biographical variables combined (gender, age, tenure, race, number of years in current position, region) significantly influences overall job insecurity amongst employees. Hence, hypothesis 1 may be accepted at the 1 per cent level of significance.

9.2 Hypothesis 2

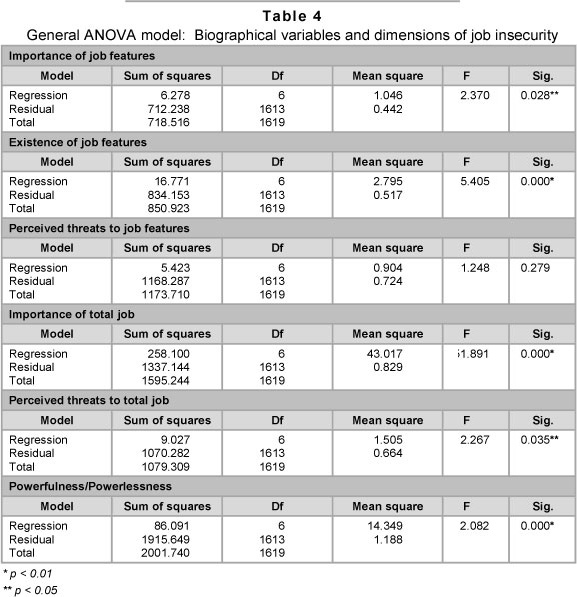

The interactive influences of all the biographical variables (gender, age, tenure, race, number of years in current position, region) results in differences in each of the dimensions of job insecurity (importance of job features, existence of job features, perceived threats to job features, importance of total job, perceived threats to total job, powerfulness/powerlessness) amongst employees respectively (Table 4).

Table 4 indicates that all of the biographical variables combined (gender, age, tenure, race, number of years in current position, region) significantly influence three of the dimensions of job insecurity (existence of job features, importance of total job, powerfulness/powerlessness) amongst employees, at the 1 per cent level of significance and a further two dimensions of job insecurity (importance of job features, perceived threats to total job) amongst employees, at the 5 per cent level of significance. Table 4 also indicates that all the biographical variables combined do not influence employees' perceived threats to job features. Hence, hypothesis 2 may be accepted in terms of all the dimensions of job insecurity except for perceived threats to job features.

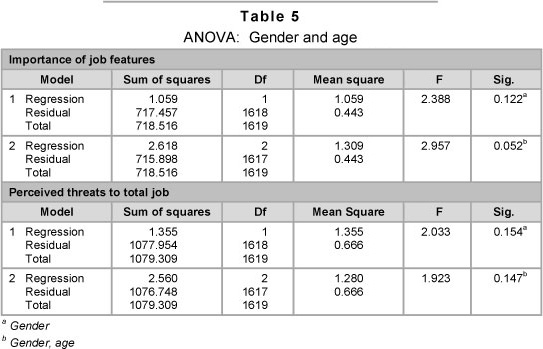

Although the interactive influence of all the biographical variables on importance of job features and perceived threats to total job are significant, in-depth analysis indicates that gender and, gender and age interactively do not significantly influence these dimensions of job insecurity (importance of job features, perceived threats to total job) (Table 5).

10 Discussion

From the results, it is evident that whilst employees experience a high level of perceived threat to their job features (Mean = 3.25) and a high level of perceived threat to their total job (Mean = 2.88), they also reflect a moderate level of powerfulness/powerlessness, which reflects their potential to experience job insecurity.

10.1 Susceptibility to experiencing job insecurity

The study aims to obtain a biographical profile of employees who may be more susceptible to experiencing job insecurity in an organisation undergoing major restructuring. The interactive influence of all the biographical variables (gender, age, tenure, race, number of years in current position, region) result in significant differences in overall job insecurity amongst employees (Table 3). Furthermore, the aggregated effects of the biographical variables on each of the dimensions of job insecurity (importance of job features, existence of job features, perceived threats to job features, importance of total job, perceived threats to total job, powerfulness/powerlessness) amongst employees were assessed. The results indicate that all of the biographical variables combined (gender, age, tenure, race, number of years in current position, region) significantly influence five of the six dimensions of job insecurity (importance of job features, existence of job features, importance of total job, perceived threats to total job, powerfulness/powerlessness), thereby reflecting no significant influence on perceived threats to job features. With regard to the influence of age, Kam (2003) finds that older people are more associated with powerlessness than younger people whilst Kinnunen et al. (2000) find that powerlessness is not significantly influenced by age. The influence of tenure on job insecurity is supported by the studies of Bender and Sloane (1999), Maurin and Postel-Vinay (2005), Ugboro and Obeng (2001) and Erlinghagen (2007) and, by Cheng and Chan (2008) in terms of threats to job features. The influence of race on job insecurity is supported by the studies of Ugboro and Obeng (2001), Burgard et al. (2006), Cheng and Chan (2008), Orpen (1993), Buitendach, Rothman and De Witte (2005) and van Wyk and Pienaar (2008). With regard to gender, Mauno et al. (2005) find that men reported more powerlessness than women; however, Kinnunen et al. (2000) find the converse. Whilst other studies did not assess the influence of region, Probst and Lawler (2006) find a significant relationship between countries and importance attached to total job.

It must, however, be noted that although the interactive influence of all the biographical variables on importance of job features and perceived threats to total job are significant, in-depth analysis indicates that gender and, gender and age interactively do not significantly influence these dimensions of job insecurity.

11 Conclusions and recommendations

The aggregated biographical variables (gender, age, tenure, race, number of years in current position, region) significantly influence overall job insecurity and, all the dimensions of job insecurity, except for perceived threats to job features. Gender and, gender and age interactively do not significantly influence these dimensions of job insecurity. However, all the other biographical variables significantly influence the dimensions of job insecurity. Evidently, biographical profiles of employees that are susceptible to experiencing job insecurity do exist. Potential reasons include family responsibilities, fear of the consequences of change and policies and procedures on redress and equity in terms of gender and race. It is therefore, recommended that change managers take cognisance of these biographical influences in attempts to reduce susceptibility to job insecurity during a process of restructuring by designing appropriate strategies and channelling them to the relevant employees. This by no means implies that different programmes and information would be given to different groups depending on gender, age, tenure, race, number of years in current position and region. Instead, it means that all demographic groupings should be given the same information using different and appropriate approaches or, by bundling the different subgroups that have different roles. For example, if employees with greater tenure are prone to feelings of powerlessness, to enhance feelings of powerfulness, these employees can be allocated the role of mentors so as to ensure a feeling of belongingness and importance. In addition, the result of females exhibiting higher levels of powerfulness than males can be strategically and diplomatically used. For example, a joyful competition may be held and females may be asked to generate all possible problem areas in the change process and males may be asked to respond with potential solutions. Interesting and fruitful outcomes can be achieved in this way thereby turning a potentially stressful change process into fun and games, which also has the potential to balance differences in powerfulness/ powerlessness. Adopting such an approach to address demographic differences ensures that strategies implemented are appreciated in the spirit of diversity management rather than an unfair labour practice or discrimination. Furthermore, programmes, information and interventions should emphasise how family responsibilities may be maintained and should focus on continuous social responsibility. Older employees should be given honest information and should be allowed to provide input into change initiatives, and the organisation's stance in terms of gender and race compositions and the direction that the organisation is taking in terms of these must be clearly communicated.

12 Limitations of the study

The study was conducted in a particular telecommunications company and the results cannot be generalised to other telecommunications companies or other organisations that are undergoing major restructuring. Furthermore, the study assessed susceptibility to experiencing job insecurity using a cross-sectional data collection method.

13 Suggestions for future research

Due to the lengthy duration of a major restructuring process, it would be valuable to assess the prevalence and magnitude of job insecurity using a longitudinal time frame such that comparisons can be made before, during and after the process of transformation so as to assess whether differences in the magnitude of job insecurity during a period of major change exist and when it is the highest.

References

ASHFORD, S.J., LEE, C. & BOBKO, P. 1989. Content, causes and consequences of job insecurity: a theory-based measure and substantive test. Academy of Management Journal, 32(4):803-829. [ Links ]

BARLING, J. & KELLOWAY, E.K. 1996. Job insecurity and health: the moderating role of workplace control. Stress and Medicine, 12:253-259. [ Links ]

BENDER, K.A. & SLOANE, P.J. 1999. Trade Union membership, tenure and the level of job insecurity. Applied Economics, 31(1):123-135. [ Links ]

BORG, I. & DOV, E. 1992. Job insecurity: correlates, moderators and measurement. International Journal of Manpower, 13(2):13-26. [ Links ]

BORG, I. & ELIZUR, D. 1992. Job insecurity: correlates, moderators and measurement. International Journal of Manpower, 13(2):13-26. [ Links ]

BRIDGES, J.S. 1989. Sex differences in occupational values. Sex Roles, 20(2):205-211. [ Links ]

BROCKNER, J., GROVER, S., REED, T.F. & DE WITTE, E.L. 1992. Layoffs, job insecurity, and survivor's work effort: evidence of an inverted-U relationship. Academy of Management Journal, 35(2): 413-425. [ Links ]

BRUN, E. & MILCZAREK, M. 2007. Expert forecast on emerging psychosocial risks related to occupational safety and health. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Luxembourg: Office for official publications of the European communities. [ Links ]

BUITENDACH, J.H., ROTHMAN, S. & DE WITTE, H. 2005. The psychometric properties of the job insecurity questionnaire in South Africa. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 31(4):7-16. [ Links ]

BURGARD, S., BRAND, J. & HOUSE, J. 2006. Job security and health in the United States. Research Report. Population Studies Centre: University of Michigan. [ Links ]

BURKE, R.J. & COOPER, C.L. 2000. The organisation in crisis: downsizing, restructuring and privatisation. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

BURKE, R.J., MATTIESEN, S.B., EINARSEN, S., FISKENBAUM, L. & SOILAND, V. 2008. Gender differences in work experiences and satisfaction of Norwegian oil rig workers. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 23(2):137-147. [ Links ]

BUSTILLO, M. & PEDRAZA, P. 2007. Job insecurity and temporary work on the increase. Retrieved June, 22, 2009 from http://www.wageindicator.org. [ Links ]

CHENG, G. & CHAN, D. 2008. Who suffers more from job insecurity? A meta-analytic review. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57(2):272-303. [ Links ]

CHOVWEN, C. & IVENSOR, E. 2009. Job insecurity and motivation among women in Nigerian consolidated banks. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 24(5):316-326. [ Links ]

DAVY, K.A., KINICKI, A.J. & SCHECK, C.L. 1997. A test of job insecurity's directed and mediated effects on withdrawal cognition. Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 18(4):323-349. [ Links ]

DEKKER, S.W. & SCHAUFELI, W.B. 1995. The effects of job insecurity on psychological health and withdrawal: a longitudinal study. Australian Psychologist, 30:57-63. [ Links ]

DE WITTE, H. 1999. Job insecurity and psychological well-being: review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(2):155-177. [ Links ]

DUNLAP, J.C. 1994. Surviving layoffs: a qualitative study of factors affective retained employees after downsizing. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 7 (4):89-113. [ Links ]

ELIZUR, D. 1994. Gender and work values: a comparative analysis. The Journal of Social Psychology, 431:201-212. [ Links ]

ERLINGHAGEN, M. 2007. Self-perceived job insecurity and social context. Discussion Paper 688. Berlin: German Institute for Economic Research. [ Links ]

ERLINGHAGEN, M. 2008. Self-perceived job insecurity and social context: a multi-level analysis of 17 European countries. European Sociological Review, 24(2):183-197. [ Links ]

FERRIE, J.E. 1997. Labour market status, insecurity and health. Journal of Health Psychology, 2:155-170. [ Links ]

FORBES, D. 1985. The no-layoff payoff. Dun's Business Month, 126(1):64-66. [ Links ]

GREEN, F. 2008. Job quality in the affluent economy: a conceptual analysis and some recent findings on trends in employment security. Presentation to the employment analysis unit, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities. [ Links ]

GREEN, F., BURCHELL, B. & FELSTEAD, A. 2000. Job insecurity and the difficulty of regaining employment: an empirical study of unemployment expectations. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 62:855-884. [ Links ]

GREENHALGH, G.L. & ROSENBLATT, Z. 1984. Job insecurity: Toward conceptual clarity. Academy of Management Review, 9(3):438-448. [ Links ]

HARPAZ, I. 1990. The importance of work goals: An international perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 21:75-93. [ Links ]

HARTLEY, J., JACOBSSON, D., KLANDERMANS, B. & VAN VUUREN, T. 1991. Job insecurity. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

HEANEY, C.A., ISRAEL, B.A. & HOUSE, J.S. 1994. Chronic job insecurity among automobile workers: Effects on job satisfaction and health. Social Science and Medicine, 38:1431-1437. [ Links ]

HELLGREN, J., SVERKE, M. & ISAKSSON, K. 1999. A two-dimensional approach to job insecurity: Consequences for employees' attitudes and well-being. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 8(2):179-195. [ Links ]

JORGE, A.C. 2005. The relationship between job insecurity, organisational citizenship behaviour and effective organisational commitment. Masters dissertation. South Africa: North-West University. [ Links ]

KAM, P.K. 2003. Powerlessness of older people in Hong Kong: A political economy analysis. Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 15(4):81-111. [ Links ]

KINNUNEN, U., MAUNO, S., NÄTTI, J. & HAPPONEN, M. 2000. Organisational antecedents and outcome of job insecurity. A longitudinal study in three organizations in Finland. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(4):443-459. [ Links ]

LABUSCHAGNE, N., BOSMAN, J. & BUITENDACH, J.H. 2005. Job insecurity, job satisfaction and work locus of control of employees in a government organisation. South African Journal of Human Resource Management, 3(2):26-35. [ Links ]

LORD, A. & HARTLEY, J. 1998. Organisational commitment and job insecurity in a changing public service organisation. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 7(3):341-354. [ Links ]

MAUNO, S. & KINNUNEN, U. 1999. Job insecurity and well-being: A longitudinal study among male and female employees in Finland. Community, Work and Family, 2(2): 147-171. [ Links ]

MAUNO, S. & KINNUNEN, U. 2002. Perceived job insecurity among dual-earner couples: Do its antecedents vary according to gender, economic sector and the measure used. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, 75(3):295-314. [ Links ]

MAUNO, S., KINNUNEN, U., MÄKIKANGAS, A. & NÄTTI, J. 2005. Psychological consequences of fixed-term employment and perceived job insecurity among health care staff. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 14(3):209-237. [ Links ]

MAURIN, E. & POSTAL-VINAY, F. 2005. The European job security gap. Work and Occupations, 32(2):229-252. [ Links ]

MOHR, G.B. 2000. The changing significance of different stressors after announcement of bankruptcy: a longitudinal investigation with special emphasis on job insecurity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21:337-359. [ Links ]

OJEDOKUN, A.O. 2008. Perceived job insecurity, job satisfaction and intention to quit among employees of selected banks in Nigeria. African Journal for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, 11(1):204-219. [ Links ]

ORPEN, C. 1993. Correlations between job insecurity and psychological well-being among white and black employees in South Africa. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 76:885-886. [ Links ]

PEDRAZA, P. & BUSTILLO, M. 2007. Determinants of subjective job insecurity in five European countries. Working paper on job insecurity. WOLIWEB D14b. Spain: Universidad de Salamanca. [ Links ]

PROBST, T.M. 2003. Exploring employee outcomes or organisational restructuring: a Solomon four-group study. Group and Organization Management, 28:416-439. [ Links ]

PROBST, T.M. & BRUBAKER, T.L. 2001. The effects of job insecurity on employee safety outcomes: cross-sectional and longitudinal explorations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(2):139-158. [ Links ]

PROBST, T.M. & LAWLER, J. 2006. Cultural values as moderators of employee reactions to job insecurity: The role of individualism and collectivism. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 55(2):234-254. [ Links ]

ROSENBLATT, A., TALMUD, I. & RUVIO, A. 1999. A gender-based framework of the experience of job insecurity and its effect on work attitudes. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 8(2):197-217. [ Links ]

SCOZZARO, P.P. & SUBICH, L.M. 1990. Gender and occupational sex type differences in job outcome factor perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 36(1):109-119. [ Links ]

SEKARAN, U. 2003. Research methods for business: a skill building approach. (4th ed.) USA: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [ Links ]

SVERKE, M. & HELLGREN, J. 2002. The nature of job insecurity: understanding employment uncertainty on the brink of a new millennium. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 51(1):23-42. [ Links ]

SVERKE, M., HELLGREN, J. & NÄSWALL, K. 2002. No security: a meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(1):242-264. [ Links ]

SVERKE, M., HELLGREN, J. & NÄSWALL, K. 2006. Job insecurity: a literature review. National Institute for Working Life. Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm University. [ Links ]

TETRICK, L.E. & QUICK, J.C. 2003. Prevention at work: Public health in occupation settings: Handbook of occupational health psychology. American Psychological Association. Washington, D.C. [ Links ]

TOLBERT, P.S. & MOEN, P.E. 1998. Men's and women's definitions of 'good' jobs: similarities and differences by age and across time. Work and Occupations, 25:147-162. [ Links ]

UGBORO, I.O., 2003. Influence of managerial trust on survivors' perceptions of job insecurity and organisational commitment in a post restructuring and downsizing environment. Journal of Behavioural and Applied Management, 4(3):230-249. [ Links ]

UGBORO, I.O. & OBENG, K. 2001. Managing the aftermaths of contracting in public transit organizations: Employee perception of job insecurity, organizational commitment and trust. Greenboro, USA: North Carolina A&T State University. [ Links ]

VAN WYK, M. & PIENAAR, J. 2008. Towards a research agenda for job insecurity in South Africa. Southern African Business Review, 12(2):49-86. [ Links ]

VILLOSIO, C., DI PIERRO, D., GIORDANENGO, A., PASQUA, P. & RICHIARDI, M. 2008. Working conditions of an ageing workforce. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. [ Links ]

Accepted: January 2012