Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versión On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.14 no.4 Pretoria ene. 2011

CSIR the motivational role of interactive control in the research sector: a case study

Kurt SartoriusI; Carolyn EitzenI; Neil TrollipII; Enrico UlianaIII

ISchool of Accountancy, University of the Witwatersrand

IIMaterial Science and Technology, Council for Scientific and Industrial Research

IIIExecutive Director Finance, University of Cape Town

ABSTRACT

The motivation of professional personnel within the confines of formal management control systems is often problematic. The paper investigates how interactive management controls can augment a performance measurement framework (PMF) in order to motivate personnel in a state-controlled research organisation. A case study method, combined with a survey, was used to test the research questions. The results indicate that the PMF motivated its researchers, as well as facilitated the achievement of organisational objectives. The results also indicated the presence of a wide range of interactive management controls that were employed to design and implement the PMF. These interactive controls included leadership enthusiasm, ownership, open communication and other informal activities that acted as a lubricant to reduce the friction of the formal PMF. In effect, these informal controls motivated researchers because they provided a series of rewards, they improved the perception of formal controls and they increased the efficiency of the organisation structure.

Key words: performance measurement framework, management interactive controls, rewards, motivation research, public sector

JEL: H83, M41, O32, P47

1 Introduction

The motivation of professionals in research organisations is often problematic within the confines of formal controls (Fitzgerald et al., 1991). In this regard, professional personnel are (often) more creative when they work in a self regulated environment and formal controls are seen as a negative influence that reduces motivation (Anthony & Govindarajan, 2001; Marginson, 2002; Bisbe & Otley, 2004). From an organisational perspective, however, the motivation of professionals must be balanced with the attainment of strategic goals that are pursued within the confines of formal controls (Bisbe & Otley, 2004).

Performance measurement is complex because it involves the simultaneous measurement of human effort, the functioning of a system and the efficiency of organisational processes within these systems (Kerssensvan Drongelen, Nixon & Pearson, 2000). The development of a performance measurement framework (PMF) in the research and development sector is especially problematic because of the non-repetitive nature of research projects (Saxberg & Slocum, 1968). Furthermore, these problems are compounded by the difficulty of isolating research returns, long time periods, multi-functional team members, the subjective nature of assessment and high levels of uncertainty (Kerssens-van Drongelen, 1999; Jamsen, Suomola & Paranko, 2002; Loch and Tapper, 2002; Baglieri, Chiesa, Grando & Manzini, 2001; Osama, 2006). Performance measurement in a State owned research organisations is further complicated because of the need to configure the interests of a diverse range of stakeholders, as well as motivate operations at a local level (Jamsen et al., 2002; Jordon & Malone, 2006).

The paper investigates how a formal control system in a state controlled research organisation can be augmented with interactive management controls in order to motivate personnel. The first research question tests whether the performance measurement framework (PMF) motivated its researchers, as well as facilitated the achievement of organisational objectives. The second research question investigates what interactive management controls were developed with respect to the design and implementation of the PMF. The third research question investigates how these interactive controls augment a PMF in order to motivate personnel. The unit of analysis is at an individual level and not at business unit level.

This paper expands the argument of Bisbe and Otley (2004) that investigates the relationship between the presence of interactive management controls and motivated (innovative) behaviour. The importance of the study is also underlined, in a more local context, by the need to integrate research in South Africa with the growth of the national economy (Wray, 2004). An outline of the remainder of the study is as follows: Section 2 develops a theoretical framework to explain how interactive controls can motivate professionals. Section 3 outlines the data and method. Section 4 introduces the case study. Section 5 presents and discusses the results. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and makes some suggestions for future research.

2 A theoretical framework

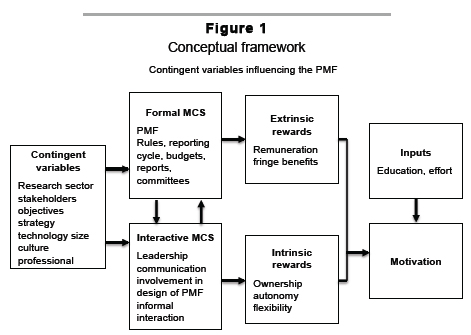

A theoretical framework, illustrated in Figure 1, proposes that a series of contingent variables influence the formal and informal management control systems in a performance measurement framework. According to Simons (1994), management control systems (MCS) are the formal, information-based routines and procedures managers use to configure organisational activities and goals. Conversely, informal MCS involve interpersonal interaction patterns within subgroups in organisations in order to fortify mutual commitment toward common goals (Jaworski, 1988). In this regard, the theoretical framework proposes that both formal and informal controls incorporate rewards that increase the level of motivation in relation to a given set of employee input The design of a PMF in the public research sector is contingent on its stakeholders, the technology environment, the company strategy, the organisation culture, size and structure and the prevailing information technology and management control systems (Pearson et al., 2000; Chiesa et al., 2007; Van Drongelen & Bilderbeek, 1999). In this regard, strategy has often been cited as the most important contingency variable (Ojanen & Vuola, 2006) because it directly influences the key actions, as well as the performance measures that are utilised to control the organisation (Merchant, 1998; Anthony & Govindarajan, 2001).

Interactive MCS

The design and implementation of a formal control system like a PMF is subject to repeated interactions between management and subordinates. Simons (1994) defines interactive controls as systems used by management to interface with subordinates regarding the formulation and implementation of formal controls. In this respect, the mediation or interactive process can be labelled as a subset of informal systems that enhance the functioning of formal controls by reducing their friction (Otley, 1999; 2003; Anthony & Govindarajan, 2001; Marginson, 2002; Kaplan & Norton, 2007). Management are expected to trigger the interactive process by showing commitment and communicating their plans, feelings and ideas. This behaviour is often less formal and allows for a culture of communication outside the formal controls, as well as encourages individual participation, autonomy and ownership in the design and implementation of formal controls (Chiesa et al., 2007; Azzone, 2006; Kerssens-Van Drongelen et al., 2000; Emmanuel, Merchant & Otley, 1985; Krause & Liu, 1993; Moon & Fitzgerald, 1996; Kerssens-Van Drongelen, 1999; Loch & Tapper, 2002).

A theory of motivation

The determinants of motivation are rooted in social psychology, neoclassical theory and management sociology (Sousa-Poza & Sousa-Poza, 2000; Mulinge & Muller, 1998; Diaz-Serrano & Viera, 2005; Levy-Garboua & Montmarquette, 2004; D'Addio, Eriksson & Frijters, 2007). Motivation, in this sense, is defined as goal-congruent behaviour by the employees (researchers) of an organisation (Robbins, 1993). The dynamics of motivation are described as an exchange process that involves the receipt of rewards for services rendered. From an employee perspective, services rendered require inputs like education, working hours, effort and the stress of physical conditions (Sousa-Poza and Sousa-Poza, 2000). Organisations incur an agency cost to motivate goal-congruent behaviour (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Control systems, therefore, must incorporate a series of rewards to induce this behaviour (Merchant, 1998; Anthony & Govindarajan, 2001). These rewards can be extrinsic or intrinsic. Extrinsic rewards include benefits received from the formal conditions of employment including remuneration, fringe benefits, job security and working conditions (Souza-Poza & Souza-Poza, 2000; McQuire, O'Donnell & Cross, 2005). Convenience extrinsic rewards encompass personal issues like living close to work, good working hours and an absence of job overload, role ambiguity and conflict (Greenberg, 1980; Price & Mueller, 1986; Kalleberg, 1977). Intrinsic rewards, on the other hand, appear to be derived from more informal interactive management processes that occur with respect to the design and implementation of strategy. These rewards include participation in decision making, ownership in the planning process, autonomy and open communication (Herzberg, Mausner & Snyderman, 1959; Greenberg, 1980; Marginson, 2002).

Interactive management controls and motivation

The relationship between motivation and the degree of formal 'static' management control systems is particularly relevant in a research organisation because there cannot be an over reliance on formal controls (Saxberg & Slocum, 1968; Bisbe & Otley, 2004). The mediation of formal control systems is explained by different interactive styles (management) or approaches to 'soften' them in a relational context. Simons (1994) defines interactive controls as systems used by management to interface with subordinates regarding the formulation and implementation of formal controls. In this regard, it has been hypothesised that these interactive control systems positively influence motivation (Simons, 1994) because they incubate intrinsic rewards like ownership, autonomy and flexibility. Interactive management controls therefore promote a more favourable input/output ratio in the Souza-Poza and Souza-Poza (2000) motivation model because they increase the rewards relative to the same set of employee inputs.

3 Data and method

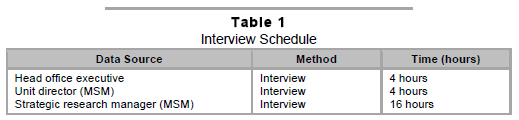

A case study method was chosen in order to describe the design and implementation of the PMF of a state controlled organisation, as well as to determine if the organisation had achieved its objectives. This method was employed, not only because of the qualitative nature of the data, but also due to the exploratory nature of the study and the fact that it allowed us to collect data from multiple sources (Leedy, 1993; Yin, 1994; Leedy & Omrod, 2001). In this regard, we obtained data from interviews, company documents, press releases and websites. The data from the case study setting were primarily collected from a number of semi-structured interviews, illustrated in Table 1. Other data, consisting of company documents, were made available to the researchers in electronic or hard-copy format or by providing appropriate websites. With respect to the interviews, a senior CSIR Group manager for Research and Development was interviewed twice before he referred the researchers to suitable managers at business unit level. Because of the wide range of responses, as well sources of data, a content analysis was used to assemble the data in themes and patterns (Breakwell, Hammond & Fife-Schaw, 2000). In order to ensure that the data had been reliably recorded, our written account of the case study was verified by the research organisation.

A survey of 39 researchers was conducted in order to determine if the PMF had motivated them, as well as facilitated the achievement of organisational objectives. The survey was also conducted to establish the presence, and extent of interactive controls, and to promote the reliability of the case study interviews. The choice of questions was largely based on the Kerssens-Van Drongelen (1999) study, as well as additional questions developed as a result of the case study interviews. Although the purposive sample size was limited, its reliability was improved because all the respondents were senior employees (researchers) who had an intimate knowledge of the division's PMF (Lenth, 2001). The survey involved the use of a five-point Likert Scale to answer a series of questions. The questionnaire contained two primary sets of questions. The first set of questions tested the respondents' level of motivation and their perception of whether the PMF had promoted the achievement of objectives. The second set of questions investigated the researchers' perception of the existence of interactive management controls with respect to the design and implementation of the PMF. Basic descriptive statistics and qualitative analysis were employed to analyse the responses.

4 CSIR materials science and manufacturing division (MSM)

4.1 Introduction

The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) in South Africa operates under the Scientific Research Council Act 46 of 1988. The CSIR and is mandated to foster industrial and scientific development in the national interest through multidisciplinary research and technological innovation, by itself or in collaboration with a range of local and international partners. The CSIR undertakes approximately 10 per cent of all research and development on the continent of Africa and recorded a total revenue of R 1.2 billion in 2007/8, with approximately 40 per cent being received by way of a parliamentary grant from the South African government through its Department of Science and Technology (DST).

The Materials Science and Manufacturing Division (MSM) is an operating business unit of the CSIR. The strategic intent of Division MSM of the CSIR is to improve industry competitiveness, national human resource development and the quality of life for all South Africans through conducting research and innovation in the fields of materials and manufacturing. The unit conducts a range of applied research, experimental development and technology transfer activities in six main competency areas. These areas include light metals, polymers and bioceramics, fibres and textiles, manufacturing science and technology, energy and sensors. The unit employs 260 personnel, of whom 205 are scientists or technologists.

4.2 The performance measurement framework

The format of the CSIR's operational plans and PMF is standardised across all of its business divisions. The Division MSM of CSIR operational plan and PMF for 2007/8, illustrated in Table 2, was based on four primary strategies that each prompted a number of key actions. These key actions, in turn, influenced the selection of performance measures for the division that are then further customised for individual researchers.

Although the Division MSM of CSIR has labelled its PMF as a balanced scorecard (BSC), it does not reflect the same dimensions or causal sequences as the Kaplan and Norton model. In effect, it is a multi-dimensional PMF that displays causal linkages between the four principal dimensions that are based on four key strategies. The four key strategies are operationalised by ten principal actions that translate into 30 performance measures (abridged version of PMF). Furthermore, a causal link exists between Strategies 2 and 4, namely, that the investment in human capital translates into operational excellence and financial sustainability. Operational excellence and financial sustainability, in turn, influence the quantity and quality of outputs (Strategy 1) which translates into research outcomes (Strategy 3) like the commercialisation of technology developments.

The management of Division MSM of CSIR's performance measurement framework operates on a quarterly basis. Each performance report compares actual progress against phased targets and a brief summary of achievements and challenges are discussed. In addition, a series of actions are listed with respect to overcoming any challenges in the quarterly results, as well as meeting the attainment of future phased targets. A revised forecast for the year is also prepared. At the end of each financial year, actual performance is compared to the annual targets for each performance measure (PM) for the division, as well as for each researcher. The PMF, in this regard, uses a five point rating scale to evaluate individual performance, ranging from 'outstanding' (rating of 1) to 'does not meet expectations' (rating of 5).

4.3 Meeting stakeholder expectations

The Division MSM of CSIR should meet the expectations of a wide range of stakeholders. Further analysis of company documents, illustrated in Table 3, identifies external stakeholders like the state, society, alliance partners, customers and employees. In this regard, the company records reflect steadily increasing outputs and stakeholder outcomes from 2005 to 2008. Publications, for example, increased by 275 per cent, the unit has also significantly increased its investments in new equipment and raised its number of international patents, thus responding to the needs of stakeholders like the state, industry, alliance partners and its customers. In addition, the satisfaction of alliance partners and customers was confirmed by a customer satisfaction rating (including alliance partners) of 86.5 per cent that manifested in a large increase in external contract income in the 2007/8 actual results. Company documents also reflect that Division MSM of CSIR has responded to the expectations of stakeholders like the employees, the state and society by achieving excellent long term results with respect to the building and transforming of human capital since 2005/6.

This progress is confirmed in the DST 2006/7 annual report in which it commends the CSIR (in aggregate) for its efforts. In order to ensure a better long term understanding of stakeholder expectations, a survey is conducted at CSIR level every 3-4 years. The survey is conducted by an independent panel that includes government departments, parastatals like ESKOM and Transnet, major industry players and the higher education sector. The survey conducted in 2008 indicated generally high levels of satisfaction but also highlighted the need for better communication of the CSIR mandate, improved promotion of the multidisciplinary nature of the organisation, further transformation at management level and concerns about intellectual property (IP) issues when partnering with the CSIR.

5 Results and discussion

The results first test if the PMF motivated the researchers, as well as facilitated the achievement of organisational objectives The results then establish the presence and extent of interactive controls (actions) before discussing how they augmented the PMF in order to influence motivation.

5.1 Did the PMF motivate researchers, as well as facilitate the achievement of strategic objectives?

The level of motivation of the researchers, as well as their perception of the role of the PMF with respect to facilitating the achievement of objectives, is illustrated in Table 4. A median score of 1 indicates a very low motivation and a score of 5 very high motivation. Case study interviews were used to support the findings of the survey. The results indicate the three levels of researchers were highly motivated by the PMF. Interestingly, the more senior the level of researcher, the higher was the level of motivation. In this regard, a Kruskal Wallis test indicated that Level 1 (more senior) researchers were significantly more motivated than Level 3 (less senior) researchers (p<0.05). Other measures used to gauge PMF related motivation indicated that the individual performance measures were achievable and appropriate and that there were consequences linked to non-achievement. Another important motivational factor was that bonuses were directly linked to performance. The case study data revealed that:

The percentage of the total bonus pool allocated to Division MSM of CSIR is determined by the unit's annual performance that is compared to the other business units of the CSIR. On an individual level, the annual bonus allocation for top achievers can amount to twice the staff member's monthly salary or even more. Staff salaries are also largely determined by their position on CSIR career ladders, and there is good alignment between the criteria used to place staff at the correct level on such ladders and important performance measures. These include the level of staff qualification as well as performance with respect to research outputs, human capital development efforts, the impact they have made in their field and the value of contract R&D secured.

The results show that a majority of the performance measures (PM) were objective thus ensuring the impartiality of the measures in a research sector context (Kerssens-van Drongelen et al., 2000). The results also indicated there was not a perception of measurement overload (number of performance measures) which is often evident in public sector organisations because of the wide range of stakeholders (Brignall, 2002; Wisniewski & Steward, 2004; McAdam, Hazlett & Casey, 2005; Chang, 2007). Finally, the results indicated the researchers were ambivalent about the fairness of the performance measures across other divisions and competence areas, as well as the controllability of their results. This is a universal problem in the research sector, however, because of the long time lags between activities and outputs, as well as the obscure nature of certain research outcomes (Kerssens-van Drongelen et al., 2000).

The role of the PMF and the achievement of objectives

The results of the survey, illustrated in Table 4 above, indicated the PMF had played a positive role with respect to the achievement of organisation objectives because it was positively aligned with these objectives. The case study data also supported the conclusion that the Division MSM of CSIR had achieved a majority of its organisational objectives for 2007/8 with respect to actual performance versus target for 30 performance measures based on the four principal strategies (see Table 2). In this regard, the case study data indicated that actual performance exceeded or met the target for seven of the eight performance measures with regard to the first strategy, namely, strengthening the science and technology base. Targets exceeded included publications, invention disclosures, collaborations, investment in new equipment, compliance with the parliamentary grant and the implementation of a research advisory panel. The results of the second strategic focus area, namely, building and transforming human capital, indicate the division achieved seven out of the eight measures but that the target to attract doctoral staff was not achieved. With regard to the third strategic focus area, the PMF indicates achievement of five of the eight performance measures but shows that revenue from intellectual property and the number of new licensing agreements were not achieved. Finally, all of the targets in the fourth strategic focus area were achieved, with particularly good results recorded for contract R&D income and net margin. In conclusion, therefore, it would appear that the PMF motivated the researchers, as well as played a positive role with respect to the achievement of organisational objectives in 2007/8. The results show that formal controls can motivate, however, the question remains whether they were augmented by interactive controls.

5.2 What interactive management controls augmented the PMF?

A range of variables, illustrated in Table 5, were used to test for the presence and extent of interactive controls that were deployed in the design and implementation of the PMF. A median score of 1 indicates a low level of interactive control. Conversely, a score of 5 indicates a high level of interactive control. Case study interviews were used in support of the observations of the survey.

The survey indicated management (leadership) were highly committed to the PMF. Case study interviews confirmed this and one interviewee said the enthusiasm of senior management was transmitted down to the three levels of researchers. This enthusiasm resulted in high levels of leadership involvement in the management of the PMF that triggered both top-down, as well as bottom-up communication. As further evidence of interactive controls, the survey results confirmed that the PMF had been clearly communicated to the respondents and, furthermore, that the PMF had helped communicate strategy to them. In this regard, the case study interviews also confirmed that the PMF targets, as well as the quarterly results, had been clearly communicated to the researchers both verbally and as result of receiving the necessary documentation.

The survey results also indicated high levels of ownership in the determination of individual performance measures and that these had been customised to take into account the particular situation of the researcher.

According to one interviewee,

esearchers have considerable leeway in a very participative environment and any researcher can initiate new research proposals. Furthermore, the performance measurement targets result from an interactive discussion rather than being imposed in a top down manner.

In this regard, the Strategic Research Manager stressed that, 'the development of individual performance targets was a bottom up process in which all researchers participated'.

The results also indicated that the performance measures and their targets were very clear to the respondents confirming the positive interactive processes of ownership and open communication. The interactive process, moreover, was consolidated with timely feedback. In this regard, the case study interviews revealed that this interactive process involved detailed feedback and support from each respondent's immediate superior. This support involved assistance to correct any problems confronting the individual researcher concerned.

The survey results showed that the PMF had been instrumental in fostering learning. The case study data suggested that learning was promoted because of the detailed interaction, challenges and discussions that occurred throughout the year. In this regard, the respondents indicated that senior personnel often provided considerable advice and guidance and that this interactive process had facilitated decisions in the division. The case study interviews confirmed that the PMF facilitated decision making because it identified specific challenges that required groups of researchers to interact before coming to a decision. Finally, the respondents were ambivalent about whether the PMF had corrected poor behaviour or influenced any reorganisation in the unit.

Although the issue of project selection was not questioned in the survey, the results of the case study interviews highlight the importance of this interactive process in a research organisation (Jamsen et al., 2002; Godener & Soderquist, 2004).

In this regard, the Strategic Research Manager said that,

MSM evaluates every new project with respect to a wide range of criteria. These include the type of research being proposed, the risk, the fit with the overall R&D portfolio and an analysis of the project financial and social return. This process is facilitated by a CSIR wide proposal management system. Furthermore, an eighteen person team of senior MSM researchers, namely, the Science and Technology Forum (SET), performs a peer review of all project proposals and progress reports which help inform the project selection process.

In conclusion, there appears to be considerable evidence of interactive controls with respect to the design and implementation of the PMF. The question remains, however, as to how these interactive controls augmented the PMF to motivate the researchers.

5.3 How did interactive controls augment the PMF to motivate researchers?

The results illustrate that the formal PMF, augmented by interactive controls, not only motivated the researchers, but also facilitated the achievement of organisational objectives. The important motivating role of the formal PMF, therefore, should not be ignored. In this regard, the PMF was linked to important extrinsic rewards like remuneration and fringe benefits that create a foundation to motivate employees. Two seminal studies contend that these extrinsic rewards, called hygiene factors, do not necessarily motivate individuals, rather their absence has a demotivating effect (Maslow, 1943; Herzberg et al., 1959). The case study results certainly confirmed that the researchers performance was linked to remuneration and that they were not dissatisfied in this respect. Furthermore, the case study illustrated that standardised salary scales were openly applied across all the divisions of the CSIR, thus ensuring that all levels of researchers knew their remuneration was on a par with their colleagues. Robbins (1993) proposes that this perception of equity is also an important motivating factor. The formal PMF, therefore, provided a baseline set of rewards that were matched with each researchers inputs that included their qualifications, experience and training. The importance of these rewards is sometimes understated in professional employee surveys (McQuire, O'Donnell & Cross, 2005). Formal controls, therefore, must incorporate a baseline set of extrinsic rewards upon which motivation is incubated.

A set of interactive controls augmented the design and implementation of the PMF to generate a secondary set of intrinsic rewards. Herzberg et al. (1959) contend that employees are motivated by satisfying experiences that are based on intrinsic rewards. The motivational role of intrinsic rewards like autonomy, ownership and open communication is especially important in the high technology and professional sectors (Abernathy & Brownell, 1997; Bisbe & Otley, 2004; Ramnall, 2004). These intrinsic rewards, therefore, augment formal extrinsic rewards without changing the individual's level of inputs like qualifications and experience. From an input-output theory perspective, the incremental rewards generated by the interactive controls would be a motivating factor because the level of inputs remain unchanged (Souza-Poza & Souza-Poza, 2000; Andriopoulos, 2001; Ramlall, 2004). Furthermore, the presence of interactive controls augments formal controls to increase motivation because they improve the perception of the fairness of formal controls (Amabile et al., 1996). Finally, interactive controls promote motivation because they influence more favourable organisation structures to work in. Transaction cost theory explains this in terms of the interactive behaviour building trust that, in turn, reduces the need for monitoring and control thus promoting self regulation, flexibility and autonomy (Ouchi, 1980; Das & Teng, 1998; Sartorius & Kirsten, 2007). These characteristics allow for flatter organisation structures that work because trust allows higher levels of flexibility and a reduced reliance on formal rules (Andriopoulos, 2001). Interactive controls, therefore, promote motivation because they act as a lubricant to reduce organisational friction, as well as allow more freedom and flexibility in the work place (Porter & Lawler, 1965; Markus, Manville & Agres, 2000). In conclusion, interactive controls motivate personnel because they augment extrinsic rewards, rather than replace them.

6 Conclusion

The paper illustrates the complex nature of controls in the research sector. A theoretical framework hypothesised that motivation is a function of total rewards less inputs. The literature also suggested that the motivation of professionals was likely to be compromised if there was an over emphasis of formal controls. In this regard, tasks in a research and development organisation are associated with a high degree of variety, uncertainty and low levels of analysability. As work related activities become less routine (analysable) and incorporate higher degrees of variety, controls should move away from formal to informal personnel controls. A case study, incorporating a survey, was then developed in order to obtain the data to test the research questions.

The results of the first research question indicated that the PMF had motivated its researchers, as well as facilitated its organisational objectives for 2007/8. This occurred because the individual performance measures were clear, achievable and linked to remuneration, as well as aligned with strategic objectives. The important motivating role of ensuring the right balance of extrinsic rewards, like remuneration and fringe benefits, cannot be over-emphasised in the professional sector. Ironically, what professionals say and think about the importance of extrinsic rewards, is often contradictory.

The results of the second research question uncovered the presence of high levels of interactive controls involved in the design and implementation of the PMF. This interactive behaviour was precipitated by upper management support and was underpinned by the fact that there were high levels of communication and ownership in the formal PMF system. This interactive behaviour was clearly more informal and spontaneous and it appeared to facilitate learning, as well as better decisions like project selection. The usefulness of the results is that they clearly identify a set of interactive controls in the PMF of a complex research environment.

The third research question then discussed how interactive controls positively influence motivation because they increase the net level of rewards in the work environment. Interactive controls, moreover, motivate employees because they improve the perception of formal controls, as well as influencing the efficiency of working structures within the organisation. The usefulness of these results is that they demonstrate how interactive controls have both psychological and economic benefits, not only from an employee perspective, but the organisation as well. The positive role of interactive controls presents the possibility that professionals can be motivated in the most problematic environments if management creates the conditions for these controls. Finally, the conclusions reached in this paper are based on the exploratory nature of the study, thus not lending themselves to wide generalisations. The application of this theory, therefore, needs to be explored in a wider context.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Professor Oerlemans for his help and guidance, as well as the two reviewers that provided major insights. Enrico Uliana gratefully acknowledges the financial support by the National Research Foundation.

References

ABERNATHY, M.A. & BROWNELL, P. 1997. Management control systems in research and development organizations: the role of accounting, behaviour and personnel controls. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22(3/4):233-248. [ Links ]

AMABILE, T.A., CONTI, R., COON, H., LAZENBY, J. & HERRON, M. 1996. Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39(5):1154-1184. [ Links ]

ANDRIOPOULOS, C. 2001. Determinants of organizational creativity: a literature review. Management Decision, 39(10):834-840. [ Links ]

ANTHONY, R.N. & GOVINDARAJAN, V. 2001. Service organizations in management control systems, (10th ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. [ Links ]

AZZONE, G. 2006. Sistemi di controllo di gestione. Metodi, strumenti, e applicazione. Milano:Etas. [ Links ]

BAGLIERI, E., CHIESA, V., GRANDO, A. & MANZINI, R. 2001. Evaluating intangible assets: the measurement of R & D Performance, Research Division Working Paper 01/49, Bocconi University Schoolof Management, Milan, Italy. [ Links ]

BISBE, J. & OTLEY, D. 2004. The effects of the interactive use of management control systems on product innovation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29:709-737. [ Links ]

BREAKWELL, G.M., HAMMOND, S. & FIFE-SCHAW, C. 2000. Research methods in psychology (2nd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

BRIGNALL, S. 2002. The unbalanced scorecard: a social and environmental critique, in Neely, A., WALTERS, A. & AUSTIN, R. (eds.) Performance measurement and management: research and action. Boston, Ma: Performance Measurement Association. [ Links ]

BRUSONI, S., PRENCIPE, A. & SALTER, A. 1998. Mapping and measuring innovation in project based firms. Working Paper, Complex Product Systems Innovation Centre, Economic & Social Research Council. [ Links ]

CHANG, L. 2007. The NHS performance assessment framework as a balanced scorecard approach : limitations and implications, International Journal of Public Sector Management, 20(2):101-117. [ Links ]

CHIESA, V., FRATTINI, F., LAZAROTTI, V. & MANZINI, R. 2007. How do measurement objectives influence the R&D performance measurement system design? Management Research News, 30(3):187-202. [ Links ]

DAS, T.K. & TENG, B-S. 1998. Between trust and control: developing confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. The Academy of Management Review, 23(3):491-512. [ Links ]

D'ADDIO, A.C., ERIKSSON, T. & FRIJTERS, P. 2007. An analysis of the determinants of job satisfaction when individuals' baseline satisfaction levels may differ, Applied Economics, 39:2413-2423. [ Links ]

DIAZ-SERRANO, L. & VIERA, J.A.C. 2005. Low pay, higher pay and job satisfaction within the European Union: empirical evidence from fourteen countries, IZA Discussion Paper No 1558. Available at: SSRN: http://ssm.com/abstract=702889 (accessed April 2011). [ Links ]

EMMANUEL, C., MERCHANT, K. & OTLEY, D. 1985. Accounting for management control (2nd ed.) London: International Thomson Business Press. [ Links ]

FITZGERALD, L., JOHNSTON, R., BRIGNALL, T.J., SILVESTRO, R. & Voss C. 1991. Performance measurement in service businesses, Copyright CIMA (2nd ed.) The Chartered Institute of Management Accountants, ISBN 09480367888. [ Links ]

GODENER, A. & SODERQUIST, K.E. 2004. Use and impact of performance measurement results in R &D and NPD: an exploratory study. R & D Management, 34(2). [ Links ]

GREENBERG, J. 1980. Attitudinal focus and locus of performance causality as determinants of equity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38:579-588. [ Links ]

HERZBERG, F., MAUSNER, B. & SNYDERMAN, B. 1959. The motivation to work. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

JAMSEN, M., SUOMALA, P. & PARANKO, J. 2002. What is being measured in R&D: contradictions between the need and practice. Available at: http://www.ipe.liu.se/rwg/igls/igls2002/paper085.pdf (accessed October 2009). [ Links ]

JAWORSKI, B.J. 1988. Toward a theory of marketing control: environmental context, control types, and consequences. Journal of Marketing, 52:23-39. [ Links ]

JENSEN, M.C. & MECKLING, W.H. 1976. Theory of the firm, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4):305-360. [ Links ]

JORDON, G.B. & MALONE, E.L. 2006. Performance assessment, Washington research evaluation network's management benchmark study. Available at: http://www.sc.doe.gov/sc5/benchmark/ch%20%20%performance%20%2006.10.02.pdf (accessed October 2009). [ Links ]

KALLEBERG, A. 1977. Work values and job rewards: a theory of job satisfaction, American Sociological Review, 42:124-143. [ Links ]

KAPLAN, R.S. & NORTON, D.P. 2007. Using the balanced scorecard as a strategic weapon. Harvard Business Review, July-August:150-161. [ Links ]

KERSSENS-VAN DRONGELEN, I.C., 1999. Systematic design of R&D PMSs. Doctoral thesis, University of Twente, the Netherlands. [ Links ]

KERSSENS-VAN DRONGELEN, I.C., Nixon, B. & Pearson, A. 2000. Performance measurement in industrial R &D. International Journal of Management Reviews, 2(2):111-143. [ Links ]

KERSSENS-VAN DRONGELEN, I.C. & BILDERBEEK, J. 1999. R &D performance measurement: more than choosing a set of metrics. R &D Management, 29(1):35-46. [ Links ]

KRAUSE, I. & LIU, J. 1993. Benchmarking R&D productivity. The Planning Forum, 21(1):16-24. [ Links ]

LEEDY, P.D. 1993. Practical research: planning and design (5th ed.) New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. [ Links ]

LEEDY P.D. & ORMROD J.E. 2001. Practical research: planning and design (7th ed.) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill. [ Links ]

LENTH, R.V. 2001. Some practical guidelines for effective sample size determination. The American Statistician, 5(3): 187-193. [ Links ]

LEVY-GARBOUA, L. & MONTMARQUETTE, C. 2004. Reported job satisfaction: what does it mean? Journal of Socio-Economics, 33(2):135-151. [ Links ]

LOCH, C.H. & TAPPER, U.A. 2002. Implementing a strategy-driven PMS for an applied research group. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 19(3):185-199. [ Links ]

MARGINSON, D.E.W. 2002. Management control systems and their effects on strategy formulation at middle manager levels: evidence from a UK organization. Management Control Systems, 23(11):1019-1031. [ Links ]

MARKUS, M.L., MANVILLE, B. & AGRES, C.E. 2000. What makes a virtual organization work? Sloan Management Review, Fall, 2000. [ Links ]

MASLOW, A.H. 1943. A theory of motivation, Psychological Review, 50:334-355. [ Links ]

MCADAM, R., HAZLETT, S.A. & CASEY, C. 2005. Performance management in the UK public sector: addressing multiple stakeholder complexity. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 18(3): 256-273. [ Links ]

MCQUIRE, D., O'DONNELL, D. & CROSS, C. 2005. Why humanistic practices in HRD won't work. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 16(1):131-137. [ Links ]

MERCHANT, K.A. 1998. Modern management control systems. Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

MOON, P. & FITZGERALD, L. 1996. Delivering the goods at TNT: the role of the performance measurement system. Management Accounting Research, 7(4):431-457. [ Links ]

MUELLER, C.W. & PRICE, J.L. 1993. Economic, psychological, and sociological determinants of voluntary turnover, The Journal of Behavioral Economics, 19(3):321-335. [ Links ]

MULINGE, M. & MUELLER, C.W. 1998. Employee job satisfaction in developing countries: the case of Kenya. World Development, 26(12):2181-2199. [ Links ]

OJANEN, V. & VUOLA, O. 2006. Coping with the multiple dimensions of R & D performance analysis. International Journal of Technology Management, 33(2-3):279-290. [ Links ]

OSAMA, A. 2006. Multi attributable strategy and performance architecture in R&D: the case of the balanced scorecard. PhD Thesis, Pardee Rand Graduate School, Santa Monica, CA. [ Links ]

OTLEY, D. 1999. Performance management: a framework for management control systems research. Management Accounting Research, 10(4):363-382. [ Links ]

OTLEY, D. 2003. Management control and performance management: whence and whither. The British Accounting Review, 35(4):309-326. [ Links ]

OUCHI, W.G. 1980. Markets, bureaucracies and clans. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(1):129-141. [ Links ]

PEARSON, A.W., NIXON, W.A. & VAN DRONGELEN, I.C. 2000. R&D as a business: what are the implications for performance measurement. R & D Management, 30(4):355-366. [ Links ]

PORTER, L.W. & LAWLER, E.E. 1965. Properties of organization structure in relation to job attitudes and job behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 64(1):23-51. [ Links ]

PRICE, J.L. & MUELLER, C.W. 1986. Absenteeism and turnover among hospital employees. Greenwitch, CT: JAI Press. [ Links ]

RAMLALL, S. 2004. A review of employee motivation theories and their implications for employee retention . Journal of American Academy of Business, 5(1/2):52-63. [ Links ]

ROBBINS, S. 1993. Organizational behaviour (6th ed.) Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

SARTORIUS, K. & KIRSTEN, J.F. 2007. A framework to facilitate institutional arrangements for smallholder supply in developing countries: an agribusiness perspective. Food Policy, 32:640-655. [ Links ]

SAXBERG, B.O. & SLOCUM, J.W. 1968. The management of scientific manpower. Management Science, 14(8):473-489. [ Links ]

SIMONS, R. 1994. How new top managers use control systems as levers of strategic renewal. Strategic Management Journal, 15(3):169-189. [ Links ]

SOUZA-POZA, A. & SOUZA-POZA, A.A. 2000. Well being at work: a cross national analysis of the levels and determinants of job satisfaction, Journal of Socio-Economics, 29(6):517-538. [ Links ]

WISNIEWSKI, M. & STEWARD, D. 2004. Performance measurement for stakeholders: the case of Scottish local authorities. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 17(3):222-233. [ Links ]

WRAY, Q. 2004. Poor research spending curbs growth, warn experts. Business Report, November 11. YIN, R. 1994. Case study research: design and method (2nd ed.) Beverly Hills, Ca: Sage Publishing. [ Links ]

Accepted: May 2011