Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versión On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.14 no.3 Pretoria ene. 2011

The effects of the global recession on the work restructuring levels of managers in the South African automotive industry

Michelle Paddey; GG Rousseau

Department of Industrial and Organisational Psychology, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

ABSTRACT

The aim of this investigation was to examine the work restructuring levels of managers in the South African automotive industry, and how these levels are affected by the global economic recession. Work restructuring was investigated from the perspective of the managers' work and family involvement levels. Data was gathered using a questionnaire that was emailed to automotive industry managers throughout South Africa. Results show that no significant gender differences occur for work involvement, family involvement, or work restructuring. A practically significant, positive relationship exists between family involvement and work restructuring. Furthermore, family involvement levels were shown not to have decreased due to the economic recession. Recommendations for organisations include implementing a gender-neutral work-family policy to assist managers in restructuring their work to accommodate family responsibilities.

Keywords: work and family involvement, work restructuring, recession, automotive industry

JEL: J22, 44, M54

1 Introduction

According to Gambles, Lewis and Rapoport (2006:4), paid work is becoming increasingly invasive and demanding in the lives of individuals, diverting time and energy from other parts of people's lives that are of equal value to them. Aspects of an individual's life that are critical for their well-being, such as time spent with children or friends, is often forced out by these work patterns. As the demands of paid work increase, so, too, do the difficulties in combining work with care responsibilities. Although working intensely may yield favourable outcomes, such as high earnings, prestige, satisfaction and promotional opportunities, this may occur only at the expense of minimising non-work obligations in order to have sufficient chance to recover from work efforts (Taris et al., 2006). Various trends, such as having to care for the children of parents who have died from HIV/AIDS, further result in it being difficult for individuals in diverse situations to conform to 'ideal' worker assumptions, while simultaneously caring for family members (Gambles, Lewis & Rapoport, 2006:61). Thus, working families that come from developing countries such as South Africa face similar dilemmas to those from industrialised nations in terms of harmonising paid work with other areas of their lives (Heymann, Earle &Hanchate, 2004), but their problems are multiplied by significantly higher care-giving burdens as well as fewer resources.

In addition to this, economic volatility together with globalisation and new technology has resulted in organisations needing to adjust their labour resources in order to remain competitive, while at the same time minimising disruption to their production processes (Schenk, 2007:414). Employers must also deal with pressures to flexibly structure their traditional employment relationships in order to deal with changes in the workplace, such as employees struggling to cope with the stress of conflicts relating to the need to balance their work and family demands (Schenk, 2007:414).

In order to understand these issues in relation to the global recession, this study aims to investigate the work restructuring levels, as well as the work and family involvement levels, of managers in the South African (SA) automotive industry. An industry, as defined by Statistics South Africa (2009a), is comprised of enterprises taking part in the same or similar types of economic activity. The National Association of Automobile Manufacturers of SA (NAAMSA, 2009) defines the SA automotive industry as being comprised of three automotive sectors, namely the retail sector, automotive parts manufacturing sector, and vehicle production sector. This research investigates the influence of economic changes on families, by aiming to discover how the current global economic recession is affecting the work-family balance of managers employed in the SA automotive industry. This is of importance because as stated by Saxbe and Repetti (2008:176), it is necessary to investigate how families are responding to changes in the economy, in order to understand the fabric ofdaily life.

A manager is defined as the individual responsible for directing and planning the work of a group of persons, supervising their work and assuming corrective action when necessary (Reh, 2009). For managers in particular, the need to restructure work for family demands is more complicated due to their large workloads together with an increased amount of work pressure being placed on them. Compared to lower-level employees, however, they also have the potential to have the greatest amount of flexibility in terms of restructuring their work.

This study is of relevance due to the fact that the SA automotive industry has been deeply affected by the current global financial crisis, with new vehicle sales in the month of May 2009 dropping 34.7 per cent year on year (Dlamini, 2009). Employees are presumably affected in terms of their workload, yet no research has been conducted on the impact of the recession on both the work and family involvement of employees in SA.

2 Literature review

2.1 Work and family involvement

Potgieter (2007) defines work (or 'job') involvement as the degree to which employees identify with their jobs, whether they regard performance at work as important and whether they actively participate in all work spheres. It also includes the psychological response to one's current job or work role and how important the job is to the individual's selfconcept and self-image (Yogev & Brett, 1985). Family involvement can be defined along the same lines, indicating the degree to which an individual is committed to and psychologically identifies with his or her family roles (Yogev & Brett, 1985). Because the roles of work and family are the most significant aspects of any individual's life (Werbel & Walter, 2002), there exists a need for employees raising children to maintain some form of balance between being involved in their work and seeing to the needs of their families. However, work-family conflicts often occur when employees experience conflict between their work and personal roles (Landy & Conte, 2010:453). This is not a problem experienced only by female employees; male employees also struggle with balancing heavy workloads with family responsibilities (Robbins, Judge & Campbell, 2010:503).

Gottfried and Gottfried (2008:33) suggest that in order to meet the dual demands of parenting and employment and maintain a balance between paid work and family involvement, employed mothers tend to redistribute their allocation of time, such as through having less sleep and less leisure time. This implies that families generate adaptations to support the needs of their children, often through the reallocation of parents' commitments. The same authors also assert that the most significant adaptation to have taken place in homes where both mothers and fathers are employed is the increase in the involvement of fathers with their children. An increase in father involvement in caretaking also offers more egalitarian models of workfamily balance as well as new role models for children of dual-earner couples (Casad, 2008:279).

2.2 Work restructuring

In the broadest sense of the word, work restructuring involves any change in the workplace with the purpose of streamlining activities, including work processes, products and changes in employment (Cheung, 2008). However, in the context of this study, the focus is on the way in which individuals restructure their working patterns to accommodate family responsibilities - that is, the ability of managers and employees to have the flexibility to determine where, how and when work is to be completed (Klein, 2008:232). This includes individuals making the decision to limit certain work behaviours in the interest of their family life (Hertz, 1986, in Karambayya & Reilly, 1992). The specific terms and conditions of employment will determine whether or not flexible work arrangements will offer an opportunity to better integrate work and family life, with the degree of control over work schedules being of particular importance (Van Doorne-Huiskes, Den Dulk & Peper, 2005:5). According to Karambayya and Reilly (1992), jobs that are most likely to have the option of work restructuring are those where one's work is performed relatively independently and when one's work hours are relatively unstructured. For these reasons, managerial and professional work can often be restructured. Yet, Gregory and Milner (2011) found that there was reluctance by organisations to allow managers to benefit from formal work-family policies, perhaps due to their abnormal working hours compared to lower-level employees. Those managers who were given the opportunity to restructure their work enjoyed discretion over the hours they worked and thus benefited from lack of a formal time management system. In certain cases, they were also more likely to work from home at times, although this often indirectly resulted in more time pressures and stress.

A study by La Valle, Arthur, Millward, et al. (2002) investigated working outside of normal work hours. The group of fathers that were most likely to work the longest hours, namely those in managerial and professional jobs, were also the least likely to be involved in caring for their children. For both mothers and fathers, long hours at work were associated with frequent disruptions to family life as well as lower involvement levels in their children's activities. According to these authors, in order for families not to be negatively affected by working during atypical times, employers must be prepared to be flexible through negotiating arrangements that meet the needs of both families and business requirements.

2.2.1 Organisational flexibility

According to Warren and Johnson (1995), a family friendly organisation is supportive of its employees who are combining family roles with paid work. Many employers and organisations have created work-family policies as a result of the changing demographics of the workforce, in order to assist in supporting the family responsibilities of their employees (Tan, 2008:5). When employees know that their organisation supports them in their care-giving roles, they can more adequately fulfil their work and family demands. Consequently, less strain will be experienced between work and family roles (Warren and Johnson, 1995). Flexible work scheduling can reduce anxiety when coordinating family and work responsibilities and thereby minimise work-family role conflict.

Porter, Bingham and Simmonds (2008:396) state that there can be no generic approach for organisations to follow when designing policies to accommodate the needs of individual employees. All stakeholders should be consulted and time must be spent ensuring that the policy fits in with both the organisational strategy and the needs of employees. Different flexible working patterns can be offered by organisations, including parttime work, job sharing, flexible working hours, leave for new parents, part year employment, working from home, career breaks and closing plants/offices for special occasions (Robbins, Judge & Campbell, 2010:503; Schenk, 2007:415).

2.3 The global economic recession

When the economic downturn, commonly referred to as the global economic recession, affected the financial markets of the developed world and spread to the world's emerging markets, it was likely that Africa would escape unaffected due to the remoteness and small size of the continent's financial sectors, which insulates these markets from the systemic issues underlying the downturn (Holmes, 2008). But although African banks have little direct exposure to those assets negatively affecting other global banks' finances, they are vulnerable to indirect effects, as the economic downturn affects the quality of their credit portfolios (International Monetary Fund, 2009). Falling demand internationally has lessened exports from Africa and a tightening of trade flows has also posed problems (Teslik, 2009).

According to Mtshali and Mahlangu (2009), on the 25th of May 2009, Statistics SA announced that the country's gross domestic product growth had slowed by -6.4 per cent in the first quarter of 2009, resulting in the announcement that SA was officially in recession, the first in 17 years. Increasing losses of jobs were predicted, as businesses in the country attempted to survive by cutting costs through retrenchments.

2.3.1 The South African automotive industry

The contribution of the SA automotive industry to SA's gross domestic product was calculated at 7.29 per cent for 2008 (NAAMSA, 2009). Although SA has been able to weather the current global financial crisis relatively well, there have been effects on the local automotive industry (Thomaz, 2009). On the 15th of May, 2009, NAAMSA (2009) released its quarterly review of business conditions of the motor vehicle manufacturing industry for the first quarter of 2009. This stated that industry employment had declined by 2571 jobs, as a result of the 'extremely difficult operating environment', characterised by lower domestic new vehicle sales as well as lower export sales. It was expected that the operating environment in all sectors of the industry would only begin to show a slight improvement domestically during the second halfof2009.

2.3. 2 How the recession has affected work and family involvement

Due to the economic downturn, many automotive industries have downsized to become more efficient. According to Gambles, Lewis and Rapoport (2006:48), downsizing results in an increase in individual workload and intensification of work, as well as the pace of work to be performed. Furthermore, employees may experience an increase in job insecurity, whether perceived or actual. This increased feeling of pressure together with a fear of unemployment may further cause employees to overwork themselves, leading to stress and burnout. In terms of family involvement, Hanes (2009) explains that the economic downturn has resulted in the adjustment of roles and relationships at home, such as by recalculating who performs the family duties. Many families have begun to balance their duties, and with many men in the manufacturing and construction sectors losing their jobs, husbands often find themselves staying at home to look after their children while their wives work. Yet, many men appreciate the positive side of this situation, namely that more time is now spent with their families than before the recession occurred.

3 Hypotheses

From the above literature review, the following problem statement was generated:

Many complex, interrelated issues exist concerning the involvement of managers in their work and family lives and how they can restructure their work to accommodate both domains. However, no research has yet been conducted on the relationship between the global recession and these interrelated issues.

Thus, a number of hypotheses were drawn to highlight the numerous unresearched areas relating to the research topic:

| H1: | Female managers will have lower levels of work involvement than will male managers. |

| H2: | Female managers will restructure their work to a greater extent than will male managers. |

| H3: | Female managers will have higher levels of family involvement than will male managers. |

| H4: | Managers who have high levels of family involvement will have higher levels of work restructuring. |

| H5: | Managers who have low levels of work involvement will have higher levels of work restructuring. |

| H6: | The current global recession results in managers experiencing lower levels of family involvement. |

| H7: | The current global recession has resulted in managers being limited in their ability to restructure their work. |

| H8: | The current global recession has resulted in managers having higher levels of work involvement. |

4 Research methodology

A quantitative research technique was utilised for this study. An electronic survey method was employed to collect the data, comprising of a five-point Likert scale.

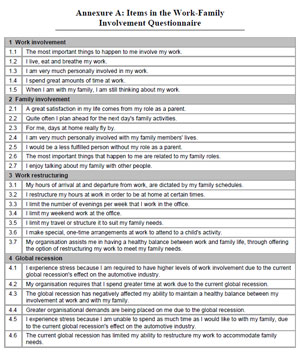

4.1 Instruments in the Work-Family Involvement Questionnaire

The questionnaire was subdivided into five sections. The first section, entitled 'Work Involvement', was based on Hackman and Lawler's (1971) adaptation of the Lodahl and Kejner (1965) scale. The scale was updated with two extra items to make the measure more relevant in the present global context.

Yogev and Brett's (1985:768) instrument was used in the section entitled 'Family Involvement'. The original Family Involvement scale by these authors comprised of 11 items, which focused on the importance of the roles of parent and spouse. Because the present study involved both married and unmarried managers, the four spouse-related items were removed from the original instrument, resulting in a seven-item scale.

Work Restructuring was based on seven open-ended questions adopted from Karambayya and Reilly's (1992) research, rephrased to be measured on a Likert scale. The questions focused on how respondents resolve the regular conflicts between work and family. One item concerning spousal needs was removed for the same reasons mentioned previously and was replaced by an item concerning whether the respondent's organisation offers the option of restructuring work to meet family needs.

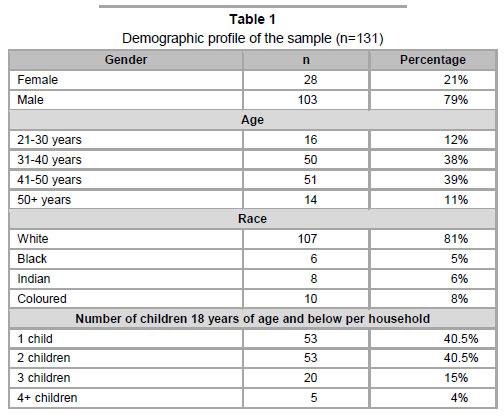

Global Recession comprised of six Likertscale items constructed by the researchers, concerning how the respondent's involvement in his or her work and family lives has been affected by the global recession. The questionnaire concluded with questions relating to demographic variables, as indicated in Table 1. A copy of the Work-Family Involvement Questionnaire is included as Annexure A.

4.2 Sampling

Data collection occurred during the months of June and July 2009 via the Internet. A nonprobability convenience and snowball sample was used. Control categories were established for the target population, including that the participants were to be managers working in the SA automotive industry and were to have at least one child 18 years of age or below, living at home at the time of the study. Ethical considerations were addressed relating to the anonymity of the responses and the voluntary nature of the research.

A total of 1148 managers were contacted via e-mail to take part in this study. Thereafter, 131 individuals fully completed the electronic questionnaire, indicating a response rate of 11.4 per cent. This sample size was deemed sufficient for the purposes of an exploratory investigation.

Table 1 summarises the demographic data collected from the sample. Notable findings are that the majority (81%) of the sample was white, a result that occurred despite hopes that the sample would be more racially diverse. It should also be observed that when compared to SA's distribution of female managers (29.9%) versus male managers (70.1%) in the first quarter of 2009 (Statistics South Africa, 2009b), it is evident that the sampled gender distribution can be deemed as being proportional with the population distribution.

4.3 Data analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for data analysis. The latter employed the statistical package STATISTICA, version 8.0. The four factors explored were Work Involvement, Family Involvement, Work Restructuring, and Global Recession, shortened to Work, Family, Restruct, and Recession.

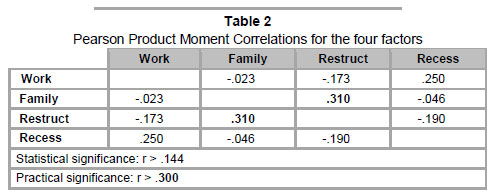

Pearson product moment correlations were calculated for the four factors together with the Chi-square statistic, which tested the statistical significance of the observed association in a cross-tabulation. For the purposes of the crosstabulations, it was calculated that responses of between 1 and 2.59 on the Likert scale would fall into the 'Low' category; between 2.6 and 3.4 in the 'Average' category; and between 3.41 and 5 in the 'High' category. Family Involvement was not included for this analysis as not enough low and average observations were available. The statistical significance level was set at a = 0.05. T-tests were conducted as univariate hypothesis tests, using the t distribution, in order to calculate whether the results were sufficient to generalise the findings for the population from which the sample was drawn.

Cronbach's coefficient alpha was calculated to assess the reliability of the summated scale scores. All scales had Cronbach coefficient alphas above the suggested 0.60 criterion for satisfactory internal consistency reliability in exploratory research (Malhotra, 2007:285). The interpolated minimum factor loading regarded significant is 0.482 for a sample size of n = 131 (Hair et al, 2006:128). Content validity was measured through expert analysis of the content, with further validation being attained through linking the items in the questionnaire with the information in the literature review.

5 Results/Findings

Table 2 indicates the Pearson Product Moment Correlations for the four factors. It is evident from this table that only the relationship between Family Involvement and Work Restructuring is practically significant, with r > 0.300. Furthermore, there is a statistically significant relationship (r > 0.144) between Work Involvement and Work Restructuring, between Work Involvement and Global Recession, and between Work Restructuring and Global Recession.

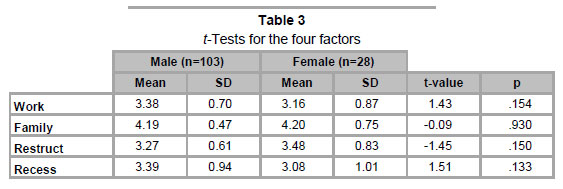

t-Tests that were conducted for the four factors resulted in all of the p-values being greater than the significance level of 0.05, as indicated in Table 3 above. There was thus insufficient statistical evidence to generalise the findings for the population from which the sample was drawn. Because these findings were not statistically significant, and in fact were not even reportable, Cohen's d was not calculated to determine practical significance.

Table 4 indicates the cross-tabulations per gender for Work Involvement and Work Restructuring. The Chi-square statistic for each relationship is also indicated. The degrees of freedom (d.f.) was calculated as 2 for each cross-tabulation. From this table it can be concluded that none of these relationships are statistically significant, as all ^-values are greater than 0.05. Because the results did not indicate statistical significance, Cramer's V was not calculated to determine practical significance.

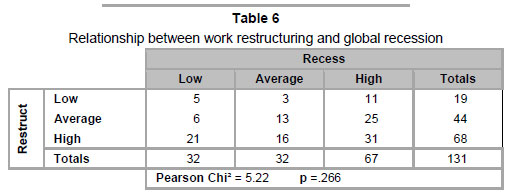

Tables 5 and 6 indicate the cross-tabulations of Work Involvement, Global Recession, and Work Restructuring. The Chi-square statistic for each relationship is also indicated. The d.f. was calculated as 4 for each table. From these tables it can be concluded that none of these relationships are statistically significant, as all p-values are greater than 0.05. Because the results did not indicate statistical significance, Cramer's V was not calculated to determine practical significance.

5.1 Hypothesis testing

In terms of gender cross-tabulations, Table 4 shows that the p-value for the relationship between gender and Work Involvement was 0.072, with the p-value for the relationship between gender and Work Restructuring being 0.796. It was thus concluded that none of these relationships were statistically significant, as the p-values were greater than 0.05. Taken into consideration with the findings from Table 3, which also indicated a lack of statistically significant relationships, hypotheses one and two were rejected.

Hypothesis three was also not supported, as the p-value for Family Involvement from Table 3 (0.930) is greater than the significance level of 0.05, indicating that this relationship is also not statistically significant. Table 2 indicates that there is a positive relationship between Family Involvement and Work Restructuring that is also practically significant, with r > 0.300 required for practical significance. This provides support for hypothesis four.

Regarding hypothesis five, it is indicated in Table 2 that there is a weak negative relationship between Work Involvement and Work Restructuring. This relationship is statistically significant, due to its correlation value of -0.173 being greater than the significance value of 0.144. However, Table 5 indicates that the relationship between Work Involvement and Work Restructuring is not statistically significant, as the p-value (0.151) is greater than the significance level of 0.05. Judgement will thus be withheld, as there is evidence partially in support of and partially in conflict with this hypothesis.

Table 2 indicates that there is no evidence in support of hypothesis six, as no statistical relationship exists between Family Involvement and Global Recession (r < 0.144). Hypothesis six is thus rejected.

In terms of hypothesis seven, according to Table 2, the correlation value of -0.190 demonstrates a negative relationship between Global Recession and Work Restructuring that is statistically significant, with r > 0.144 required for statistical significance. However, Table 6 points to the relationship between Global Recession and Work Restructuring not being statistically significant, as the p-value (0.266) is greater than the significance level of 0.05. Judgement will thus be withheld, as there is evidence both supporting and not fully supporting this hypothesis.

Finally, according to Table 2, the relationship between Work Involvement and Global Recession has a correlation value of 0.250, indicating a statistically significant positive relationship between these two factors. However, Table 5 indicates that this relationship is not statistically significant, as the p-value (0.166) is greater than the significance level of 0.05. Judgement will thus be withheld for hypothesis eight, as there is evidence partially in support of and partially in conflict with this hypothesis.

6 Discussion

The literature (such as Burgess, Burke & Oberklaid, 2006) suggests that men have higher levels of work involvement than females, due to gender stereotypes as well as the fact that it is often more difficult for men to reduce their involvement in work (Gambles, Lewis and Rapoport, 2006:73). However, hypothesis one was rejected in this study, suggesting that men and women are equally involved in their work. This supports findings by Mantler and Murphy (2005) as well as Singh, Finn and Goulet (2004), who found no significant gender differences in levels of work involvement. Long work hours and high levels of work involvement are characteristics of managerial roles (Byron, 2005), whether a male or female fills that role.

In terms of hypothesis three, it was predicted that female managers would experience higher levels of family involvement than their male counterparts. This, however, was not confirmed. The researchers note that the reported high levels of family involvement may be due to socially desirable answers. Regardless, the fact that male and female managers are equally involved in their family domains is a positive result, as this suggests that traditional gender stereotypes and social norms, whereby females are more involved in the area of family responsibilities, is changing. The literature does confirm this, with studies by Burnett, Gatrell, Cooper and Sparrow (2010), Gregory and Milner (2008) as well as Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel (2007) indicating rising levels of family involvement by fathers, as well as increased levels of paternity leave being taken.

Positively, it can also be noted that hypothesis six was rejected, with no support that family involvement levels across genders have decreased due to the current global recession. Families are apparently not suffering during the recession by having 'managerial parents' exert less effort and fewer hours into the family domain. White (2009, in Shim, 2009) explains that many parents in the United States are in fact creating more time to spend with their families during the recession, as they feel that they have a greater need to become involved in the lives of their children. This is an important finding because it demonstrates that the commitment parents have towards their families is not affected by external economic factors.

Interestingly, hypothesis two was rejected, indicating no gender differences in restructuring work to accommodate family needs. This is contrary to the literature, in which it is stated that women generally restructure their work to a greater extent than men (Karambayya & Reilly, 1992; Brett & Yogev, 1988:166). It should be noted that the latter studies were conducted a number of years ago, and thus might be outdated. As with levels of family involvement, gender stereotypes have changed and men seem to be playing a greater role in caring for their children together with their wives, as opposed to being less involved in the need to restructure their work to be available for family responsibilities.

Support was, on the other hand, received for hypothesis four, indicating conclusively that those managers with high levels of family involvement do restructure their work to a greater extent. This is in contrast to Brett and Yogev (1988:167,170), who found that for both males and females, family involvement was not correlated with work restructuring levels. The implication of this finding is that in order to spend more time with their families, managers ensure that they restructure their work through accommodations such as flexitime or time off for time worked, usually in consultation with their employers. Taken into consideration with hypothesis six discussed above, it can be deduced that managers who restructure their work would be inclined to continue to do so throughout the recession due to the fact that their family involvement levels have not decreased during this time.

Because no conclusive evidence was gained for hypothesis five, it cannot be fully supported that managers with low levels of work involvement would have higher levels of work restructuring. This is in line with evidence from the literature. For example, Brett and Yogev (1988:170) state that females who are highly involved in their work restructure significantly less than those less involved in their work, but male's work restructuring levels are not related to their work involvement levels.

It was also not proven that the current global recession has resulted in managers having lower levels of work restructuring (hypothesis seven), or having higher levels of work involvement (hypothesis eight). The researchers could find no literature regarding work restructuring differences due to the recession and as a result this indicates a potential area for future research. The fact that inconclusive results were produced in terms of work involvement was against the researchers' expectations, as the literature points towards increased work involvement levels as organisations deal with effects ofthe recession, such as downsizing. A possible reason might be that all sectors of the automotive industry were included in the sample. Thus, although members of manufacturing organisations might be faced with a greater workload and work pressures, those in the retail sector might face the opposite, with decreased vehicle sales during this slow economic period.

6.1 Implications for automotive industry organisations

Taken holistically, the findings from this study have important implications for automotive industry organisations. According to Britain's Department of Trade and Industry (2004, in Porter et al., 2008), employers that are dedicated to obtaining the best workforce and becoming an employer of choice will consult with their employees, implement a policy of work-life balance and regularly monitor its impact, developing it further as and when required. Many employers worldwide have indeed implemented work-family (or familyfriendly) policies to assist in supporting their employees' family responsibilities and to aid in creating a work environment in which employees' family demands are supported. These policies should be implemented in the automotive industry organisations studied for this investigation, as employees who wish to be more involved in their families are also finding it necessary to restructure their work despite changing economic climates. Employees who are highly involved in their work despite having families are likely to gain from the implementation of such policies, as these policies will likely reduce the levels of work-family conflict currently experienced (Russo & Waters, 2006) through the formalisation of employer accommodations.

Due to the fact that it was found in this study that no gender differences occurred for work involvement, family involvement or levels of work restructuring, a further implication of this study's findings is that organisations should make all work-family policies available to both male and female employees without the occurrence of bias or gender preconceptions. Male managers should therefore not be ostracised for wishing to make use of employer accommodations such as flexitime. Indeed, current research indicates that it is necessary to formalise the flexibility provided to employed fathers in the form of work-family policies that afford rights such as paternity leave (Gregory & Milner, 2011). Presently, more mothers than fathers still make use of flexible working patterns, partly because organisations fail to acknowledge the social changes regarding the role of fathers in parenting (Burnett, Gatrell, Cooper & Sparrow, 2010). Thus in practice, few workfamily policies have achieved the status of being gender-neutral.

In addition, organisations must ensure that they consult with their employees about their needs and implement accommodations that will be most effective in allowing employees to restructure their work. Work-family policies must have a degree of flexibility and cannot be rigidly implemented based on what has worked effectively in other organisations. They must be tailored to the needs of managers through a process of consultation, due to the fact that employees are unlikely to benefit from generically-designed work-family policies (Russo & Waters, 2006).

In doing so, family-friendly policies can provide increased profits through producing more committed, loyal employees, who will be likely to return after a family-related absence, and less likely to leave their employers in general (Halpern, 2008:220). An organisation should develop a culture of flexibility so that a variety of work arrangements can be incorporated. This will ensure that the organisation achieves a competitive advantage. Employees will also benefit from being provided with greater individual control to achieve both personal and professional objectives.

6.2 Recommendations for automotive industry organisations

As a result of this study, automotive industry organisations can make use of the following recommendations to assist managers in obtaining a balance between their work and family involvement:

• Consult with managers about their individual needs regarding the balance between their work and family lives. Uncover whether managers are satisfied with the current flexibility granted to them by the organisation in terms of restructuring their work to accommodate family responsibilities.

• Based on this process of consultation, develop and implement a work-family policy that will serve to formalise the organisation's standpoint on what type of accommodations are approved by the organisation and which are not acceptable.

• Inform managers about this policy, emphasising the accommodations that the organisation is willing or able to make. Ensure that it is understood and that managers recognise that it applies across genders, free from discrimination or stereotypes.

• Continually evaluate this policy to determine its effectiveness and assess whether it has positively affected the family lives of managers. Make relevant changes based on feedback from managers.

• Implement counseling services whereby employees can discuss personal issues relating to the effect of the recession on their personal lives, such as workplace anxiety, stress, job insecurity and difficulties in balancing work and family involvement.

• Due to the fact that female respondents in this study were found to have levels of work involvement equal to their male counterparts, organisations should attempt to develop female managers (as well as lower-level employees) through appropriate mentoring programmes. This will assist women's progression to higher organisational levels, thereby recognising and rewarding them for their high levels of work involvement.

• Yogev and Brett (1985) state that when the pressures of a working wife are present, then both the husband and wife are required to participate in the management of work demands that affect the family. A coordinated pattern of responsibilities and routines that are adequate to manage these demands are often developed. Thus, automotive industry organisations should ensure that their managers take the personal responsibility for restructuring their work through discussing alternative work restructuring arrangements with their employers as well as with their spouses. This will ensure that managers understand all options available to them when attempting to balance their involvement in their work and family lives.

7 Conclusion

In the current economic downturn, organisations will succeed if they are able to adapt to new realities as well as control their expenditures (Mullet, 2009, in Thomaz, 2009). Thus, by automotive industry organisations implementing work-family policies and formalising flexible working patterns, they can use the aforementioned to their advantage in order to produce cost savings for the organisation as well as see that the needs of their managers are met during the global recession. For example, instead of an organisation retrenching an employee, he or she could be provided the opportunity to make use of job sharing, thereby allowing the employee more time to be involved with his or her family while also saving his or her job. If managers are given resources to more effectively balance their work and family lives, they will respond proactively by making use of such work-family policies (Russo & Waters, 2006).

The patterns found in this research provide a glimpse into the current values of society. Because some ofthe results were inconclusive, more research is required to fully understand this topic. It would also be valuable to investigate the different sectors of the automotive industry independently, or extend the study to other industries. Despite this, the current investigation provides valuable insight into the work restructuring levels of managers during a tough economic time in SA. It contributes to the literature on work restructuring levels of managers and also provides insight into how the global recession has affected the work and family involvement of managers in the SA automotive industry.

References

BRETT, J.M. & YOGEV, S. 1988. Restructuring work for family: how dual-earner couples with children manage, in Goldsmith, E.B. (ed.) Work and family: theory, research and applications. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

BURGESS, Z., BURKE, R.J. & OBERKLAID, F. 2006. Workaholism among Australian psychologists: gender differences. Equal Opportunities International, 25(1):48-59. [ Links ]

BURNETT, S.B., GATRELL, C.J., COOPER, C.L. & SPARROW, P. 2010. Well-balanced families? A gendered analysis of work-life balance policies and work family practices. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 25(7):534-549. [ Links ]

BYRON, K. 2005. A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2):169-198. [ Links ]

CASAD, B.J. 2008. Issues and trends in work-family integration, in Marcus-Newhall, A., Halpern, D.F. & Tan, S.J. (eds.) The changing realities of work and family: 277-291. United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

CHEUNG, C. 2008. Lagged harm of work restructuring and work alienation to work commitment. International Journal of Employment Studies, 16(2):170-207. [ Links ]

DLAMINI, A. 2009. South Africa: recession adds more strain to motor industry. [Online] Available at: http://allafrica.com/stories/200906030756.html [Accessed 2009-07-14] [ Links ].

GAMBLES, R., LEWIS, S. & RAPOPORT, R. 2006. The myth of work-life balance: the challenge of our time for men, women and societies. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. [ Links ]

GOTTFRIED, A.E. & GOTTFRIED, A.W. 2008. The upside of maternal and dual-earner employment: a focus on positive family adaptations, home environments, and child development in the Fullerton longitudinal study, in Marcus-Newhall, A., Halpern, D.F. & Tan, S.J. (eds.) The changing realities of work and family : 25-42. United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

GREGORY, A. & MILNER, S. 2008. Fatherhood regimes and father involvement in France and the UK. Community, Work & Family, 11(1):61-84. [ Links ]

GREGORY, A. & MILNER, S. 2011. Fathers and work-life balance in France and the UK: policy and practice. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 31(1/2):34-52. [ Links ]

HACKMAN, R. & LAWLER, E.E. 1971. Employee reactions to job characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 55:259-286. [ Links ]

HAIR, J.F.t,hBLACK, W.C., BABIN, B.J., ANDERSON, R.E. & TATHAM, R.L. 2006. Multivariate data analysis (6thed.) Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

HALPERN, D.F. 2008. Part IV Introduction, in Marcus-Newhall, A., Halpern, D.F. & Tan, S.J. (eds.) The changing realities of work and family: 218-220. United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

HANES, S. 2009. How the recession is reshaping the America family. [Online] Available at: http://www.csmonitor.com/2009/0614/p13s01-usec.html [Accessed 2009-07-13] [ Links ].

HEYMANN, J., EARLE, A. & HANCHATE, A. 2004. Bringing a global perspective to work and family: an examination of extended work hours in four countries. Community, Work and Family, 7(2):247-272. [ Links ]

HOLMES, J.A. 2008. Africa dodges the financial bullet, but recession is another matter. [Online] Available at: http://www.cfr.org/publication/17853/africa_dodges_the_financial_bullet_but_recession_is_another_matter.html?breadcrumb=/issue/publication_list%3Fid%3D492%26page%3D2 [Accessed 2009-07-13] [ Links ].

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 2009. Regional economic outlook: sub-Saharan Africa. [Online] Available at: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/reo/2009/afr/eng/sreo0409.pdf [Accessed 2009-07-13] [ Links ].

KARAMBAYYA, R. & REILLY, A.H. 1992. Dual earner couples: attitudes and actions in restructuring work for family. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(6):585-601. [ Links ]

KLEIN, D. 2008. Business impact offlexibility: an imperative for working families, in Marcus-Newhall, A., Halpern, D.F. & Tan, S.J. (eds.) The changing realities of work and family: 232-244. United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

LA VALLE, I., ARTHUR, S., MILLWARD, C., SCOTT, J. & CLAYDEN, M. 2002. Happy families? Atypical work and its influence on family life. Bristol: Policy Press. [ Links ]

LANDY, F.J. & CONTE, J.M. 2010. Work in the 21 st century: an introduction to industrial and organizational psychology (3rded.) Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. [ Links ]

LODAHL, T. & KEJNER, M. 1965. The definition and measurement of job involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 49:24-33. [ Links ]

MALHOTRA, N.K. 2007. Marketing research: an applied orientation (5thed.) Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson. [ Links ]

MANTLER, J. & MURPHY, S. 2005. Job involvement in academics. [Online] Available at: http://httpserver.carleton.ca/~jmantler/pdfs/Faculty%20job%20involvement%20report.pdf [Accessed 2009-09-25] [ Links ].

MTSHALI, L.Z. & MAHLANGU, D. 2009. South Africa is now in recession. [Online] Available at: http://www.thetimes.co.za/News/Article.aspx?id=1007190 [Accessed 2009-07-13] [ Links ].

NAAMSA 2009. Quarterly review ofbusiness conditions: motor vehicle manufacturing industry: 1st quarter, 2009. [Online] Available at: http://www.naamsa.co.za/papers/2009_1stquarter/ [Accessed 2009-07-14] [ Links ].

NEPOMNYASCHY, L. & WALDFOGEL, J. 2007. Paternity leave and fathers' involvement with their young children: evidence from the American Ecls-B. Community, Work and Family, 10(4):427-453. [ Links ]

PORTER, C., BINGHAM, C. & SIMMONDS, D. 2008. Exploring human resources management. United Kingdom: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

POTGIETER, T. 2007. Stress management, well-being and job satisfaction, in Werner, A. (ed.) Organisational behaviour: a contemporary South African perspective: 314-342. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

REH, F.J. 2009. Manager. [Online] Available at: http://management.about.com/od/policiesandprocedures/g/manager1.htm [Accessed 2009-07-15] [ Links ].

ROBBINS, S.P., JUDGE, T.A. & CAMPBELL, T.T. 2010. Organizational behaviour. London: Pearson. [ Links ]

RUSSO, J.A. & WATERS, L.E. 2006. Workaholic worker type differences in work-family conflict: The moderating role of supervisor support and flexible work scheduling. Career Development International , 11(5): 418-439. [ Links ]

SAXBE, D.E. & REPETTI, R.L. 2008. Taking the temperature of family life: preliminary results from an observational study, in Marcus-Newhall, A., Halpern, D.F. & Tan, S.J. (eds.) The changing realities of work and family: 175-193. United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

SCHENK, H. 2007. Career management and performance, in Meyer, M. (ed.) Managing human resource development: an outcome based approach: 397-423. Durban: LexisNexis. [ Links ]

SHIM, J. 2009. Recession buys parents more time with kids at school. [Online] Available at: http://www.thegrio.com/2009/09/the-recession-has-more-black-parents-planning-to-volunteer-at-schools.php [Accessed 2009-09-25] [ Links ].

SINGH, P., FINN, D. & GOULET, L. 2004. Gender and job attitudes. Women in Management Review, 19(7):345-355. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA 2009a. Manufacturing: production and sales (preliminary). [Online] Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P30412/P30412May2009.pdf [Accessed 2009-07-13] [ Links ].

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA 2009b. Quarterly labour force survey: quarter 1, 2009. [Online] Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02111stQuarter2009.pdf [Accessed 2009-07-14] [ Links ].

StatSoft Inc. 2008. STAT1ST1CA (data analysis software system), version 8.0, www.statsoft.com. [ Links ]

TAN, S.J. 2008. Part I Introduction, in Marcus-Newhall, A., Halpern, D.F. & Tan, S.J. (eds.) The changing realities of work and family: 4-8. United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

TARIS, T.W., BECKERS, D.G.J., VERHOEVEN, L.C., GEURTS, S.A.E., KOMPIER, M.A.J. & VAN DER LINDEN, D. 2006. Recovery opportunities, work-home interference, and well-being among managers. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(2):139-157. [ Links ]

TESLIK, L.H. 2009. Crisis guide: the global economy. [Online] Available at: http://www.cfr.org/publication/19710?gclid=CNKa7O6605sCFR7yDAodDXg3Lw [Accessed 2009-07-13] [ Links ].

THOMAZ, C. 2009. Industry in turmoil. [Online] Available at: http://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/industry-in-turmoil-2009-02-20 [Accessed 2009-07-14] [ Links ].

VAN DOORNE-HUISKES, A., DEN DULK, L. & PEPER, B. 2005. Part I Introduction, in Peper, B., van Doorne-Huiskes, A. & den Dulk, L. (eds.) Flexible working and organisational change: the integration of work and personal life. United Kingdom: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

WARREN, J.A. & JOHNSON, P.J. 1995. The impact of workplace support on work-family role strain. Family Relations, 44(2):163-169. [ Links ]

WERBEL, J. & WALTER, M.H. 2002. Changing views of work and family roles: A symbiotic perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 12(3):293-298. [ Links ]

YOGEV, S. & BRETT, J. 1985. Patterns of work and family involvement among single - and dual-earner couples. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70(4):754-768. [ Links ]

Accepted May 2011