Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

On-line version ISSN 2222-3436

Print version ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.14 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2011

ARTICLES

Task-based factors influencing the successful functioning of copreneurial businesses in South Africa

Shelley FarringtonI, Elmarie Venter I; Carey EybersI; Christo BoshoffII

IDepartment of Business Management, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

IIDepartment of Business Management, Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

Globally, evidence exists to suggest that the number of copreneurial businesses or spousal partnerships are on the increase. The primary objectives of this study are to identify the task-based factors influencing the effectiveness of a copreneurial business, to propose a conceptual model based on these factors and to subject the model to empirical testing. The model is empirically tested among copreneurial businesses to assess potential relationships between selected independent variables (shared dream, leadership, personal needs alignment, division of labour, complementary skills, supportive employees, competencies and adequate resources) and measures of copreneurial success (perceived success and financial performance). In order to address the primary objective of this study, a questionnaire was administered to a sample of 1548 respondents (spouses in business together) of which 380 questionnaires were useable for statistical analysis. The empirical results revealed that apart from division of labour all the other factors investigated exert a significant influence on the successful functioning of copreneurial businesses.

Key words: copreneurs, husband-and-wife teams, successful copreneurial businesses, copreneurship as a route to entrepreneurship

JEL L25, 26

1 Introduction, problem statement and research objectives

Copreneurships are a particular type of family business where married couples or couples in a marriage-like relationship, share in the ownership, management and responsibility of a single business (Rutherford, Muse & Oswald, 2006; Barnett & Barnett, 1988). Although the concept of copreneurship has been around for almost twenty years (Barnett & Barnett, 1988), as they become more common these types of family businesses are receiving an increasing amount of attention in the small and family business literature (Marshack, 1994; Rutherford et al., 2006; Muske & Fitzgerald, 2006; Poza & Messer, 2001; Rowe & Hong, 2000). According to Fitzgerald and Muske (2002), much of the growth in entrepreneurship is attributed to an increasing number of wives becoming involved in business partnerships with their husbands.

To date, however, little research has been conducted on copreneurs in business together and few theoretical guidelines exist to assist these couples to manage their copreneurial relationship (Jaffe, 1990; Marshack, 1994; Muske & Fitzgerald, 2006; Poza & Messer, 2001; Rowe and Hong, 2000). While numerous popular articles on the subject exist, these are not research-oriented but rather anecdotal or based on single-case studies (Marshack, 1993). This limited scholarly research on gender ownership makes it difficult to do research on the phenomena of copreneurship. In addition, the term "copreneur" is not widely recognised, even by organisations that represent or support small businesses, and it is typically associated with the role of women as working spouses in small family firms (O'Connor, Hamouda, McKeon, Henry & Johnston, 2006).

According to Cole and Johnson (2007) copreneurs face the unique challenge of balancing their romantic personal relationship with their professional business one. In their research Danes and Olson (2003) found that when couples work together the potential for tension and conflict is high. Given these unique challenges the question thus arises as to what conditions are necessary to ensure the successful creation and maintenance of such copreneurial businesses, and ultimately the survival of these family businesses.

Despite their unique nature and challenges, a husband and wife in a family business, are basically a team just like any other within an organisational context. Consequently it is important that the spouses work together in their business as a team if they want their copreneurship to be successful. Teamwork and collaboration are critical to the success of any business partnership (Gage, Gromala & Kopf, 2004; Ward, 2004). This being the case, the organisational concepts of effective teams are as relevant to spousal teams as they are to other teams. To function effectively, certain basic elements are required to exist in the working conditions of a team; the extent to which these elements are present increases the chances of a successful team outcome (Hofstrand, 2000). Against this background the primary objectives of this study are to identify these basic elements or task-based factors influencing the effectiveness of a copreneurial business, to propose a conceptual model based on these factors and to subject the model to empirical testing.

The lack of existing theory and empirically based research on copreneurs or copreneurial teams has necessitated a triangulation of theories and a multidisciplinary approach in order to identify the factors influencing the effective functioning of a copreneurial business. In this study, theories from the Organisational Behavior (teamwork) as well as family business literature have been adopted to explain this phenomenon in the field of family business. O'Connor et al. (2006) also emphasised the importance of teamwork in their research on copreneurial businesses.

For the purpose of this study the concepts "copreneurs", "copreneurial businesses" and "husband-and-wife teams" are used interchangeably and synonymously.

2 Attributes of effective copreneurial teams

Literally thousands of studies in almost every type of organisational context have examined factors that influence team effectiveness (Hitt, Miller & Colella, 2006; Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006). Consequently, there is a large body of research on how to build effective teams and on identifying factors related to team effectiveness (Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006; Robbins, 2003; Sheard & Kakabadse, 2002). Numerous general models of effective teams have been proposed by, amongst other, Hellriegel, Jackson, Slocum, Staude, Amos, Klopper, Louw and Oosthuizen, (2004); Kreitner and Kinicki (1995); Mondy and Premeaux (1995); and Robbins (2003). These and the classic models of Campion, Medsker and Higgs (1993), Gladstein (1984) and Hackman (1987) condense current knowledge about what makes teams effective (Robbins, 2003). These normative models are useful for highlighting the necessary factors to be considered when teams are configured (Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006). Although these models differ in many respects, they all, implicitly or explicitly, address similar issues and offer similar suggestions on how to design effective teams. These issues are of nearuniversal importance to all teams and the suggestions offered can be applied to almost any team, in almost any context (Guzzo & Dickson, 1996; Yancey, 1998).

After a careful analysis of various theoretical models, team-based research and lists describing the characteristics of and requirements for effective teams, four general categories or themes are proposed representing summaries of the key components of previous theories, namely, context, composition, structure, and processes. In addition, each general category comprises a number of underlying components. These four categories reflect the necessary criteria, characteristics and essential requirements for effective teams and high levels of team performance.

The input-process-output (I-P-O) model, which proposes that inputs lead to processes that in turn lead to outcomes, is the most common framework used to explain the way in which team design elements interact to enable effective team outcomes (Barrick, Stewart, Neubert & Mount, 1998; Campion et al., 1993; Groesbeck & Van Aken, 2001). The I-P-O model posits that a variety of inputs combine to influence intra-group processes, which in turn affect team outputs. Inputs refer to the composition of the team in terms of the constellation of individual characteristics and resources at multiple levels (individual, team, organisation). Processes refer to the activities that team members engage in, in combining their resources to resolve (or fail to resolve) task demands. Processes thus mediate the translation of inputs to outcomes. Output has three facets: performance judged by relevant others external to the team; meeting of team member needs or team-member satisfaction; and viability or the willingness of members to remain in the team. These tripartite facets capture the prevalent conceptualisation of team effectiveness (Barrick et al., 1998:377; Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006).

In her model, Gladstein (1984), for example, categorises the various factors influencing group effectiveness into input and process variables. Input variables are further divided into group composition (adequate skills, heterogeneity, organisational tenure and job tenure); group structure (role and goal clarity, specific work norms, task control, size and formal leadership); and resources available and organisational structure (available training, markets served, group performance rewards and supervisory control). In Hackman's (1990) input-process-output model, inputs include task design, group composition, training, resources, and some elements of context. Internal processes include communicating, managing conflict, making decisions, and learning. Outputs include productivity, quality, innovation, customer satisfaction, and employee satisfaction (Howard, Foster and Shannon, 2005).

Taking cognisance of the input-processoutput (I-P-O) model, the general categories identified, namely, context, composition, structure and processes are further delineated into either input or process variables. Context, com-position and structure are all categorized as input variables because of the high degree of correlation that has proved to exist between them (Barrick et al., 1998; Olukayode & Ehigie, 2005).

A considerable amount of research has examined various inputs of the I-P-O model (Howard et al., 2005). For example, Campion et al. (1993) have found that almost all of their proposed input variables or design characteristics of work groups, relate to one or more of their three criteria of team effectiveness. These results have been confirmed in a follow-up study (Campion, Papper & Medsker, 1996). Consequently, it was decided to focus on the input factors, namely context, composition and structure (and their underlying components) and the impact they have on husband and wife teams in business. Considering the influence that input factors have on the ability of team members to complete the task at hand, these factors can also be described as task-based factors.

3 Proposed conceptual model

The factors included in the conceptual model are justified by sufficiency of theory in both the teamwork and family business literature. As such the model is based on an integration of prior findings and theories on team effectiveness and supported by empirical or anecdotal evidence found in the family business literature.

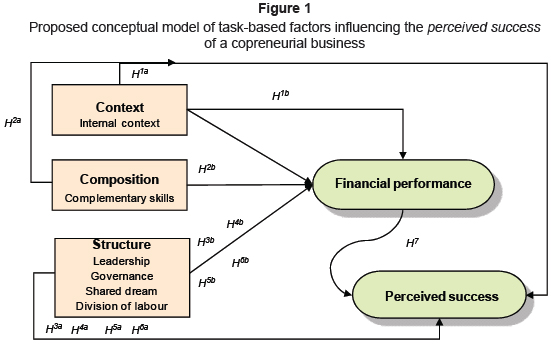

The conceptual model proposed in this paper suggests that three input or task-based variables impact the effective functioning of copreneurial businesses, namely context, composition and structure. These three taskbased factors are divided into six underlying independent variables, namely: internal context; complementary skills; division of labour; shared dream; governance; and leadership.

Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesized relationships between the above mentioned independent variables, and the dependent variable, namely, perceived success. Furthermore, although financial performance is not a task-based factor as such, assessing the financial performance of a business is necessary when establishing the overall successful functioning thereof. As a result, financial performance has been included as an intervening or mediating variable in the conceptual model. Anecdotal and empirical evidence supporting the hypothesized relationships is discussed in the paragraphs below.

3.1 Dependent variable: perceived success of the copreneurial business

As illustrated in Figure 1, the dependent variable in this study is the perceived success of a copreneurial business. Perceived success is defined as the degree to which the copreneurs find their ongoing involvement in the copreneurship as satisfying as well as beneficial to their family, marriage and personal development. The satisfaction of family members involved in a family business is commonly associated with success in family business research (Handler, 1991; Ivancevich, Konopaske & Matteson, 2005; Sharma, 2004; Venter, 2003).

3.2 Independent variables: task-based factors influencing copreneurial businesses

In this study the factor, internal context refers to the internal environment of the copreneurial business, specifically in terms of access to adequate and suitable resources, information, equipment, employees and working conditions. For any team of people to perform successfully, an internal organisational context should exist that provides team members with the necessary support and infrastructure to complete the task at hand effectively (Hitt et al., 2006; Robbins, 2003). In studies on team effectiveness, significant relationships and positive correlations have been found between variables relating to context (resources, information and training, amongst others) and measures of team effectiveness (Campion et al., 1993; Doolen, Hacker & Van Aken, 2006; Hyatt & Ruddy, 1997). The following hypotheses have been formulated to test the impact of internal context on the success of a copreneurial business:

H1a: There is a positive relationship between internal context and the perceived success of the copreneurship.

H1b: There is a positive relationship between internal context and the financial performance of the copreneurship.

Teams function most effectively when composed of highly skilled and competent individuals who can offer a diverse set of complementary skills and experiences (Hitt et al., 2006; Robbins, 2003). In this study complementary skills refers to the copreneurs being competent and being competent in different areas. Team member heterogeneity in terms of abilities and experiences has been found to have a positive effect on team performance (Gladstein, 1984; Hackman, 1987). For family businesses managed by teams of siblings for example, it is also suggested that the siblings should have a more or less even distribution of complementary skills and talents among them (Aronoff, Astrachan, Mendosa & Ward, 1997; Gersick, Davis, McCollom Hampton & Lansberg, 1997; Lansberg, 1999).

According to Tompson and Tompson (2000) spouses in business together should possess individual skills that are compatible with each other. Similary, both Nelton (1986) and O'Connor et al. (2006) assert that when spouses can effectively combine their individual skills in a complementary manner, their copreneurship is more likely to be successful. Synergy among copreneurs will only be possible if individual skills are mutual and complementary (Roha & Blum, 1990). Based on the discussion above, the following hypotheses have been formulated:

H2a: There is a positive relationship between the complementary skills among copreneurial couples and the perceived success of the copreneurship.

H2b: There is a positive relationship between the complementary skills among copreneurial couples and the financial performance of the copreneurship.

A team's leadership is crucial to the effectiveness of the team, and the team leader strongly influences all aspects of a team's composition and behaviour (Hitt et al., 2006; Ivancevich et al., 2005). Cowie (2007) reports a significant positive relationship between leadership and the ability of a team to operate efficiently. Several studies (Gladstein, 1984; Guzzo & Dickson, 1996) have also found support for a relationship between leadership and measures of team effectiveness. In his research on the contributions of leadership styles to family business success, Sorenson (2000) found that participative leadership was significantly and positively associated with financial performance. Both participative leadership and referent leadership were positively and significantly related to family outcomes. Sorenson (2000) concludes that referent, and in particular participative leaders, enable family businesses to obtain desired outcomes for both the business and the family.

According to Marshack (2002) copreneurs must openly and honestly decide how leadership is going to develop within their business. Leadership, that emphasizes flexibility, a win-win philosophy, quality over quantity, robustness and prudence, is essential for success. In addition, success in business would not be possible without leadership that build the trust and confidence of employees (Marshack 2002). In this study leadership refers to the spouse(s) having a consultative or participative leadership style, having referent and expert leadership, and being visionary. It is consequently hypothesised that:

H3a: There is a positive relationship between leadership and the perceived success of the copreneurship.

H3b: There is a positive relationship between leadership and the financial performance of the copreneurship.

Governance structures, such as advisory boards, boards of directors and frequent family meetings, are increasingly emphasised as important correlates with both family business longevity over multiple generations and firm performance (Astrachan & Aronoff, 1998; Astrachan & Kolenko, 1994). In this study the factor Governance refers to the overall existence of governance structures, policies and procedures in the copreneurship.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the implementation of governance structures, policies and procedures promotes family business success, stimulates growth and contributes to the continuity as well as sustainability of the family business (Aronoff et al., 1997; Lansberg, 1999; Ward, 2004). Hauser (2004) maintains that well-governed families also manage well-governed businesses, which in turn earn consistently high profits. In her study, Venter (2003) reports a positive relationship between the existence of governance processes and planning, and the continued profitability of the business. Adendorff (2004) also reported a positive relationship between profitability and perceived good governance. Effective teams in general have norms or codes of conduct that govern their behaviour (Keen, 2003, Northouse, 2004). Hyatt and Ruddy (1997) found a significant positive relationship between norms and roles among team members and manager ratings of team effectiveness. Although Governance structures in copreneurial businesses are usually informal (Governance for the family business, 2008), based on the discussion above, it has been hypothesised that:

H4a: There is a positive relationship between governance and the perceived success of the copreneurship.

H4b: There is a positive relationship between governance and the financial performance of the copreneurship.

According to Lansberg (1999: 75) a shared dream among family members is described as a "collective vision of the future that inspires family members to engage in the hard work of planning and to do whatever is necessary to maintain their collaboration to achieve their goals". In this study the factor shared dream refers to whether the dreams that the spouses have for themselves in their copreneurship are aligned with each other's dreams, their involvement in the business is entirely voluntary, and they agree on the future direction of the business.

Ring and Van de Ven (1994) contend that a shared vision (dream) promotes coherence in stakeholders' expectations and opinions on organisational goals, and consequently promotes cooperative behaviour through clarified role interactions. Similarly, Lansberg (1999) is of the opinion that a balance between individual dreams and the shared dream is essential to the psychological well-being of all family members, as well as to the harmony of the family business. In their study, Mustakallio, Autio and Zahra (2002) found support for their hypotheses that a shared vision was associated with increased decision quality and increased managements' decision commitment, respectively. In addition, they found that a shared vision was positively associated with strategic decision quality and commitment. Associations between the existence of a mission and indicators of business effectiveness, namely return on assets, return on investments, sales growth, market share, quality, employee satisfaction, and product/service development, have also been found to be significant (Denison, Lief & Ward, 2004).

Studies among teams in general show a significant relationship between the existence of clear goals and measures of team effectiveness (Doolen et al., 2006; Guzzo & Dickson, 1996). Hyatt and Ruddy (1997), for example, found a significant positive correlation between commitment to common goals and goal orientation among team members, and team effectiveness. According to Guzzo and Dickson (1996), team goals often coexist with individual goals, but when team and individual goals are in conflict with one another, dysfunctions can result. In her study, Cowie (2007) reported a significant positive relationship between the commitment to and existence of clear and challenging goals, and financial performance.

According to Van Auken and Werbel (2006), as well as Campbell (2008) copreneurs should ensure that their vision concerning the business, its goals, risks and rewards, is shared between them. If their dream for the business is not shared, feelings of resentment may arise, ultimately leading to marital strife (Campbell, 2008). Charles (2008) asserts that copreneurs should not only have a shared dream concerning the business, but, should also share personal and relationship goals to avoid drifting apart. Based on the above it is hypothesised that:

H5a: There is a positive relationship between the existence of a shared dream between copreneurial couples and the perceived success of the copreneurship.

H5b: There is a positive relationship between the existence of a shared dream between copreneurial couples and the financial performance of the copreneurship.

In effective teams, members mutually agree on responsibilities (Keen, 2003; Robbins, 2003) and job descriptions, and individual tasks and responsibilities are specified and clearly laid out (Hitt et al., 2006). In this study division of labour refers to each spouse being assigned a clearly demarcated area of authority and responsibility in the business, as well as the spouses being in agreement on this assignment.

Several studies (e.g. Ancona & Caldwell, 1992; Keck, 1997) show that functional assignment diversity (the existence of distinct organisational roles or positions) affects firm performance. Roure and Keeley (1990), for example, report that the degree to which team members hold a range of key positions is associated with entrepreneurial success. Similarly, Beckman and Burton (2005) found strong support for their hypothesis that management teams with functional assignment diversity will reach firm outcomes more quickly than teams that do not. In her study, Cowie (2007) found a significant positive relationship between clear responsibilities and the willingness of team members to cooperate with and support each other. Handler (1991) concluded from her study that separate positions and areas of responsibility promote a positive relationship between family members in business together.

Both, Marshack (1994) and Robin (2007) contend that copreneurs should occupy specific and clearly defined roles within their businesses, and the more distinct these tasks and responsibilities are, the more beneficial it will be for the business. According to Tompson and Tompson (2000), clearly defined roles ensure that respect and order is maintained between the spouses. Similarly, Blum and Roha (1990), as well as Gale (2002), contend that clearly defined roles (clear division of labour) significantly reduce the likelihood of power battles and rivalry between the spouses. Without clear roles and job descriptions for spouses in business together, problems, conflicts and resentments may rise (Husbands, wives and business, 2008).

Based on the discussion above, the following hypotheses have been formulated:

H6a: There is a positive relationship between the division of labour amongst copreneurs and the perceived success of the copreneurship.

H6b: There is a positive relationship between the division of labour amongst copreneurs and the financial performance of the copreneurship.

3.3 Itermediate or mediating variable: financial performance

For the purpose of this study financial performance refers to positive trends of growth in number of employees and profits, as well as increasing revenue experienced by the copreneurial business. Financial performance is commonly regarded as a measure of success and has been used by numerous authors to distinguish between successful and unsuccessful successions (Flören, 2002; Venter, 2003), successors (Goldberg, 1996), family businesses (Sharma, 2004; Ward, 2004) and even teams in general (Ivancevich et al, 2005; Mondy & Premeaux, 1995; Northouse, 2004).

In her study Venter (2003) found a positive relationship between the financial security of the owner-manager and the business, and the satisfaction with the succession process, as well as between the financial security of the owner-manager and the business, and the continued profitability of the business after the succession. Adendorff's (2004) research also revealed a positive relationship between profitability and the ability to satisfy stakeholders' interests. Tagiuri and Davis (1992) indicated that one of the main goals of the owner-managers of successful smaller family businesses is to provide themselves with financial security and benefits. Similarly, O'Connor et al. (2006) observed that spouses tend to establish businesses out of a desire to create wealth. It is doubtful whether stakeholders in a copreneurial business would find their involvement as satisfying were their business to experience financial difficulties.

The following hypothesis is thus formulated:

H7: There is a positive relationship between the financial performance of the copreneurial business and the perceived success of the copreneurial business.

4 Methodology

4.1 Sample and sampling method

No complete lists distinguishing family from non-family businesses are available in South Africa (Van Der Merwe & Ellis, 2007; Venter, 2003). Three databases of family businesses were, however, identified and used to initiate the sampling process in this study. The first database used is one developed by Venter (2003) in her study on the succession process of small and medium-sized family businesses in South Africa. Venter's (2003) database contains a list of 1 038 family businesses throughout South Africa. The second database of family businesses used, was one developed by the Department of Business Management at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. The names and details of 749 small and medium-sized family businesses appear on this list. The third database used was one developed by Farrington (2009) for her study on sibling partnerships among small and medium-sized family businesses in South Africa. This database contains the names of 1 323 siblings involved in South African family businesses. These three databases served as the initial sampling frame (list of names), from which potential sampling units were identified. In addition, an advanced Google search of South African websites resulted in many names of businesses involving copreneurs.

Respondents were identified be means of convenience snowball sampling which was initiated by contacting family businesses on the three databases, as well as those identified via the Google search. Once identified, suitability and willingness to participate in the study were confirmed telephonically, details were captured on a database, and respondents were requested to identify other copreneurial businesses that could be approached to participate in this study. These potential respondents were then also contacted telephonically and the process was repeated. This sampling technique and methodology is consistent with that of other family business researchers who have been constrained by the lack of a national database on family firms (Sonfield & Lussier, 2004; Van Der Merwe & Ellis, 2007; Venter, 2003).

4.2 Method of data collection

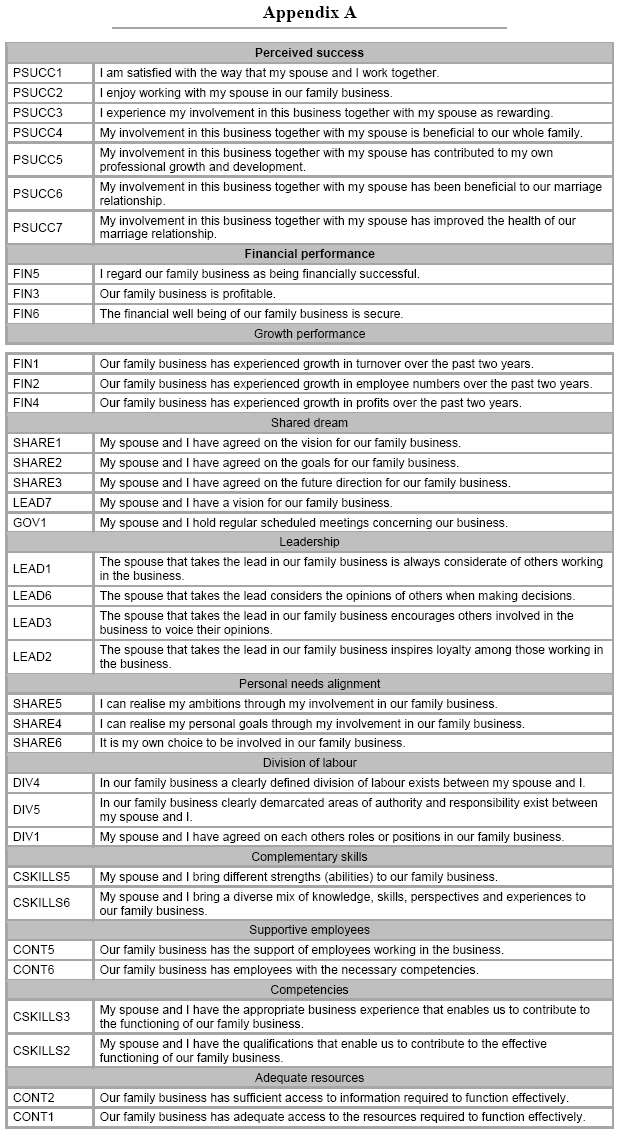

Each factor under investigation (construct) was clearly defined and then operationalised. Operationalisation was done by using reliable and valid items sourced from validated measuring instruments used in previous studies, as well as several self-generated items based on secondary sources. These items were then used to empirically test the relationships hypothesised in the conceptual model.

Section 1 of the measuring instrument consisted of 58 statements (items) relating to various task-based factors influencing the perceived success of a copreneurial business. Using a 7-point Likert-type scale, respondents were requested to indicate their extent of agreement with regard to each statement. The 7-point Likert-type scale was interpreted as 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. Demographic information pertaining to both the respondent, the marriage relationship as well as the copreneurial business was requested in Section 2. Structured questionnaires (1548) were made available to identified respondents by means of a convenience snowball sampling technique. The data collected from 380 usable questionnaires was subjected to various statistical analyses. An exploratory factor analysis was undertaken and Cronbach-alpha coefficients were calculated to assess the discriminant validity and reliability of the measuring instrument. The relationships proposed in the conceptual model were assessed by means of multiple regression analyses.

4.3 The realised sample

The demographic characteristics of the sample show that most of the respondents were female (55 per cent), between the ages of 40 and 51 years old (37 per cent), and white (98 per cent). Almost half (49 per cent) indicated having been in business together with their spouse for 10 years or less, and 74 per cent reported operating their copreneurship from their family home. Most (50 per cent) of the respondents indicated employing 10 or less people, and operating their copreneurial businesses in either the retail/services (30 per cent) or hospitality (22 per cent) industries.

Most (52 per cent) respondents reported that the ownership of their copreneurial business is divided equally between them and their spouse, with the vast majority (92.1 per cent) being actively employed in the business. Although 32.1 per cent of the respondents reported that leadership is shared equally between them and their spouse, 31.8 per cent indicated that the spouse that was most knowledgeable took the lead among them.

4.4 Discriminant validity and reliability

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted to identify the unique factors present in the data and as such assess the discriminant validity of the measuring instrument. The software programme SPSS 15 for Windows was used for this purpose.

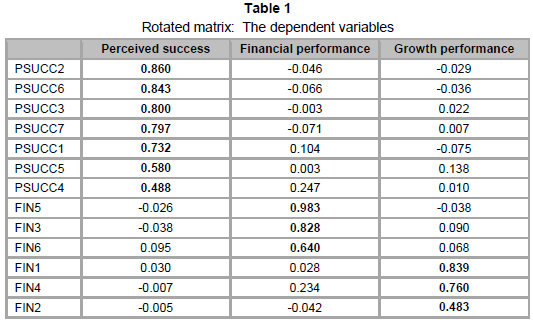

In order to conduct the factor analysis the data was divided into two models. The first model related to the dependent variables and the second to the independent variables. For the model relating to the dependent variables, principal axis factoring with an oblique rotation was specified as the extraction and rotation methods. Principal component analysis with a varimax rotation was specified as the extraction and rotation methods for the model relating to the independent variables. In determining the factors (constructs) to extract for each model the percentage of variance explained and the individual factor loading were considered (see Tables 1 and 2).

Although all seven items intended to measure perceived success loaded together onto one construct as expected, the six items measuring financial performance, did not. These six items loaded onto two separate factors, that were named financial performance and growth performance. These three factors explain 69.19 per cent of the variance in the data and are regarded as the dependent variables in this study. Factor loadings of > 0.4 (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham, 2006) are reported for all factors, consequently providing evidence of construct and discriminant validity for the measuring scales.

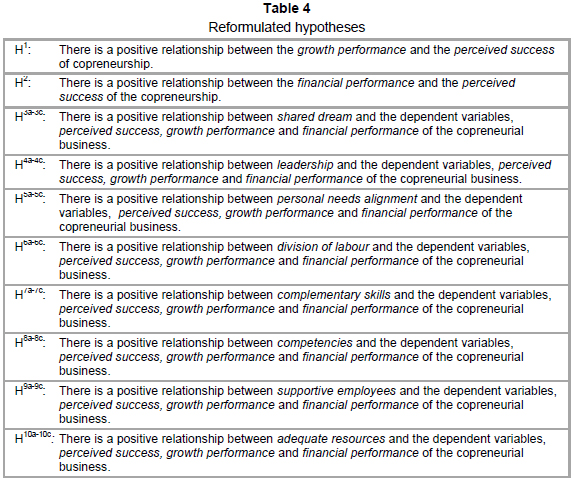

With regard to the exploratory factor analyses undertaken on the independent variables (Table 2), the original six factors did not load as expected, instead eight new factors emerged. Of the original six items intended to measure shared dream, three items loaded together i.e. SHARE1, SHARE2 and SHARE3. In addition, two other items, namely LEAD7 and GOV1 also loaded onto shared dream. Shared dream explains 32.65 per cent of the variance in the data. The other three items (SHARE4, SHARE5 and SHARE6) originally expected to measure the construct Shared dream loaded together onto a separate factor. Based on the nature of the items that loaded together, it was decided to name this factor personal needs alignment. Personal needs alignment explains 6.39 per cent of the variance in the data.

Only four items used to measure the construct leadership loaded together onto one factor.

Leadership explains 7.06 per cent of the variance in the data. Three of the items (DIV1, DIV4 and DIV5) expected to measure the construct division of labour loaded onto one factor. The items DIV2, DIV3 and DIV6 did not load as expected and were therefore not used in subsequent statistical analysis. Division of labour explains 5.9 per cent of the variance in the data. Only two (CSKILLS5 and CSKILLS6) of the six items expected to measure the construct complementary skills loaded onto one factor. Complementary skills explains 5.48 per cent of the variance in the data. The items CSKILLS2 and CSKILLS3 loaded together onto a separate factor which was named competencies. Competencies explain 4.63 per cent of the variance in the data. Only two (CONT5 and CONT6) of the 6 items expected to measure the construct internal context loaded onto one factor. This factor was named supportive employees and explains 4.80 per cent of the variance in the data. The items CONT3 and CONT4 did not load as expected and were therefore not used in subsequent statistical analysis. The remaining two factors (CONT1 and CONT2) loaded together separately onto another factor named adequate resources, which explains 3.53 per cent of the variance in the data.

The eight independent variables cumulatively explain 70.46 per cent of variance in the data. Factor loadings of > 0.4 (Hair et al., 2006) are reported for all factors, which provides evidence of construct and discriminant validity for the measuring scales.

Based on the results of the factor analyses and the items that loaded on to each construct, the operational definitions were reformulated. The operationalisation of the constructs identified, the minimum and maximum factor loadings as well as the Cronbach-alpha coefficients for each of these constructs are summarised in Table 3. In addition, Cronbach-alpha coefficients of greater than 0.70 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994; Peterson, 1994) are reported for all constructs, suggesting that reliable measuring scales were used to measure the constructs under investigation.

4.5 Revised theoretical model and hypotheses

Based on the results of the factor analyses the proposed conceptual model (Figure 1) was modified (Figure 2) and the hypotheses reformulated in Table 4 below.

4.6 Multiple linear regression

Multiple linear regression is a tool for predicting a dependent variable based on several independent or explanatory variables (Cooper & Schindler, 2007; Hair, Anderson, Tatham & Black, 1998) and as such allows for the simultaneous investigation of the effect of two or more independent variables on a single dependent variable. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to assess whether the independent variables as identified in this study exert a significant influence on the dependent variables namely perceived success, financial performance and growth performance of a copreneurial business. As such three separate regression models were used and the results thereof are discussed in the paragraphs below. In addition to serving as the dependent variables, financial performance and growth performance, together with the other independent variables, were also modelled as independent variables influencing the perceived success of a copreneurial business.

4.6.1 Regression analysis results: perceived success of a copreneurship

Based on the multiple regression analysis it has been established that the independent variables explain 64.8 per cent of the variance in the perceived success of a copreneurial business. As can be seen in Table 5, a positive relationship was found between perceived success and the independent variables, namely shared dream (t=2.094; p<0.05), leadership (t=7.258; p<0.001), personal needs alignment (t=11.654; p<0.001) as well as complementary skills (t=3.599; p<0.001) and competencies (t=2.942; p<0.01). In other words, the more that spouses agree on the future direction of their business, exhibit leadership that is inspirational, considerate and participatory, and are able to realise their personal ambitions through their involvement in the business, the more likely the spouses will be satisfied with their involvement in their copreneurial business. Similarly, the more that spouses are competent to manage their business and possess competencies that complement each other, the more likely the copreneurs are to experience their involvement in the copreneurship as satisfying, as well as beneficial to their marriage and personal development. Based on these results, support is thus found for hypotheses H3a, H4a, H5a, H7a and H8a The results of this study reveal a negative relationship between supportive employees and perceived success (t=-1.992; p<0.05). This negative relationship implies that the more competent and supportive the employees, the less likely the spouses are to experience their involvement in business together as satisfying and beneficial. As a result, no support was found for hypothesis H9a, which proposed a positive relationship between supportive employees and perceived success.

The results of the regression analysis further reveal that neither the financial nor the growth performance of the business has an impact on the perceived success of a copreneurship. In addition, the results also show that division of labour and adequate resources do not influence the extent to which respondents experience their involvement in the copreneurship as satisfying and beneficial to their marriage and personal development. Consequently, no support was found for hypotheses H1, H2, H6a and H10a.

4.6.2 Regression analysis results: financial performance of a copreneurship

With regard to the influence of the independent variables on the financial performance of a copreneurial business it is evident that the independent variables explain 32.9 per cent of the variance in the financial performance of the copreneurship. Table 6 illustrates that a positive linear relationship emerged between personal needs alignment and financial performance (t=3.901; p<0.001), implying that the more the spouses can realise their personal goals in the business and that their involvement is voluntary, the better the financial performance of their business is likely to be.

A positive linear relationship was found between complementary skills and financial performance (t=2.140; p<0.05), as well as between competencies and financial performance (t=4.052; p<0.001). In other words the more complementary the spouses' skills and abilities are to one another, and the more competent the spouses are to perform the tasks required of them to run their business, the more likely the business is to be perceived as financially profitable and secure.

A positive linear relationship was also found between supportive employees and financial performance (t=4.615; p<0.001), as well as between adequate resources and financial performance (t=3.099; p<0.01). This means that the more competent and loyal the employees of the business are and the more access the business has to necessary resources, the more likely the business is to perform financially. However, the results show that a shared dream, leadership and division of labour do not influence the financial performance of a copreneurship in this study. Based on these results, hypotheses H5c, H7c, H8c, H9c and H10c cannot be rejected, whereas hypotheses H3c, H4c and H6c are rejected.

4.6.3 Regression analysis results: growth performance of a copreneurship

The findings of this study (see Table 7) show that the independent variables explain 22.8 per cent of the variance in the growth performance of the business. Table 7 reveals a positive linear relationship between complementary skills and growth performance (t=3.494; p<0.01). This means that the more complementary the spouses' skills and abilities are to one another the more likely the business is to experience growth. Also illustrated in Table 7, is a positive linear relationship between supportive employees and growth performance (t=6.010; p<0.001). In other words, the more loyal and competent the employees of the business are, the more likely the business is to experience growth. Support has therefore been found for hypotheses H7b and H9b, meaning that these hypotheses cannot be rejected, whereas hypotheses H3b, H4b, H5b, H6b, H8b and H10b are rejected. In other words, the results indicate no support for a positive linear relationship between shared dream, leadership, personal needs alignment, division of labour, competencies and adequate resources, and the dependent variable growth performance of a copreneurship.

Thirteen significant relationships were identified between the various independent and the dependent variables. These significant relationships are summarised in Figure 3. It should be noted that the model, as illustrated in Figure 3, was not tested as a single model, but split into three models with each being subjected to a regression analysis.

5 Conclusions and recommendations

The results of the study show that the copreneurial businesses involved in this study perceived the following task-based factors as influencing the success of their business, namely: shared dream, leadership, personal needs alignment, complementary skills, supportive employees, competencies and adequate resources.

A shared dream and leadership play a significant role in determining the satisfaction levels of copreneurs in a copreneurial business. The findings of this study show that the more that spouses agree on the future direction of their business and exhibit leadership that is inspirational, considerate and participatory, the more likely the spouses will experience their involvement in the copreneurship as satisfying, as well as beneficial to their marriage and personal development. In addition, the ability of spouses to realise their personal ambitions (personal needs alignment) through their involvement in the business, influences their degree of satisfaction with their involvement in their copreneurial business, as well as their perception of its benefits for their marriage and personal development. Furthermore, the more that spouses are able to realise their personal ambitions through the business the better the financial performance of their business is likely to be.

When spouses share a future vision for their business it drives their sense of purpose for working together. Finding and emphasizing this common ground, keeping the final destination in mind, and understanding what is required to get there, is of key importance to a successful copreneurship. In order to ensure a shared dream for their business, spouses should ensure that both of them are committed to this dream and that an overlap exists between their individual dreams or personal ambitions, and their shared dreams. As such the spouses should be able to live out their own dreams and achieve their personal ambitions through their involvement in their copreneurial business. A shared dream between spouses should provide direction, be clearly specified and be revised when necessary.

When spouses work together in a business, it is important that they develop their own leadership and decision-making style, which is best suited to their particular circumstances. Despite the fact that husbands tend to be the primary decision-makers in copreneurial businesses (O'Connor et al., 2006), the ideal is when leadership between the spouses emerges naturally, the leader is comfortable with power, and is the most competent person to take the lead. In addition to being inspirational, considerate and participatory, it is important that the leader can be trusted to make good decisions and is future orientated.

The findings of this study show that the more competent the spouses are to manage their business, the more likely the copreneurs are to experience their involvement in the copreneurship as satisfying and beneficial to them, and the more likely the business is to be perceived as financially profitable and secure. In addition, the study reveals that not only should the spouses be competent, their competencies should also complement each other's. The more that spouses possess competencies that complement each other's, the more likely the copreneurs are to experience their involvement in the copreneurship as satisfying as well as beneficial to their marriage and personal development. In addition, the more complementary the spouse's skills and abilities are to one another, the more likely the business is to perform financially and experience growth. When copreneurs appropriately combine their varied knowledge, talents, unique skills and experiences, the resulting synergy raises their overall level of performance, and brings many benefits to their copreneurial business. To ensure that these benefits materialise, areas of authority and responsibility should be assigned according to the strengths and particular area of expertise of each spouse. In similar vein, Robin (2008) asserts that when dividing the labour between the spouses care should be taken not to divide the work according to traditional gender stereotypes, as is often the case (Marshack, 1994; O'Connor et al., 2006), but rather on the basis of individual abilities, preferences and skills.

The competence and loyalty of employees has a significant positive influence on the ability of a copreneurship to perform financially and to experience growth. Competent and supportive employees make a vital contribution through expanding the knowledge base of the copreneurial business by bringing additional qualifications and skills; by showing objectivity; and promoting accountability and professionalism. It is important that care should be taken that employees do not play the spouses off against each other and that the spouses should be in agreement and have a clear policy on employees. In addition, it is important that loyalty and respect for the spouses be developed and maintained among employees.

The results of this study do, somewhat surprisingly, reveal a negative relationship between supportive employees and perceived success. Having competent and loyal employees working in a copreneurship reduces the likelihood that spouses will experience their involvement in business together as satisfying and beneficial to their marriage and personal development. A possible explanation for this finding could e that spouses involved in coprenerial businesses with competent and loyal employees, are probably less likely to work as many hours and as closely with their spouse, than in businesses where competent employees do not exist. This reduced contribution to the business and reduced interaction with their spouse, could result in their not experiencing their involvement in the business as satisfying or beneficial to their marriage and personal development.

In addition, the results indicate that whether the copreneurship has adequate resources or not has no influence on the extent to which respondents experience their involvement in the copreneurship as satisfying and beneficial. However, the results do show that the more access the business has to the necessary resources, the more likely the business is to perform financially. If financially possible, copreneurs should ensure that their business has access to adequate and suitable resources, information, equipment, employees, and working conditions.

Surprisingly the results of this study show that that neither the financial nor the growth performance of the business has an impact on the perceived success of a copreneurship. Considering the definition of perceived success as operationalised in this study, namely the degree to which the copreneurs find their involvement in the copreneurship as satisfying as well as beneficial to their marriage and personal development, one would expect a relationship to exist. The findings imply that the performance (financially or growth) of the copreneurial business has no impact on whether the copreneurs experience their involvement as satisfactory or beneficial.

6 Implications for theory and research

The value of this study lies in the expression "forewarned is forearmed". Anticipating potential obstacles and challenges allows one to implement steps to address these issues the moment they arise or to potentially avoid them altogether. Although many of the task-bassed factors identified as influencing successful copreneurships have been shown as important determinants of success within other contexts and fields of study, this study, however, relates them specifically to spouses working together in family businesses. As such insights are provided into the conditions that should prevail to improve the chances of a successful working arrangement between husbands and wives.

This study has added to the body of family business research by investigating a particularly limited segment of the literature, namely copreneurships in family businesses. The use of a relatively large empirical sample size in this study, also adds to the field of family business which has traditionally been characterised by smaller samples and qualitative research.

This study has integrated many of the traditional theories of teamwork, and has tested these theories among spousal teams in family businesses. By investigating these teams within the context of the family business, the present study has also contributed to the fields of organisational behaviour and general psychology by either confirming or refuting many of these theories within a specific context.

7 Limitations and future research

The use of a snowball convenience sampling technique is a limitation of this study. Nonprobability sampling introduces a source of potential bias into the study, and consequently the findings can not be generalised to the general family business population. Future research should strive to develop a more comprehensive database from which probability samples can be drawn. In addition, the data collected relies on the self-report of respondents. Relying on one-time individual self-report measures to assess constructs, is another important limitation.

One important limitation of this study is that the proposed conceptual model focuses exclusively on task-based factors and fails to include relational-based factors affecting the successful functioning of copreneurial businesses. Relational-based factors refer to factors that influence the interaction between people when they work together as a team and include amongst others, fairness, mutual respect and trust, open communication, spousal relationship, family harmony, commitment, non-family members and balance between work and home. These relational-based factors should also be investigated and incorporated into the conceptual model that describes the factors influencing the successful functioning of copreneurial businesses.

As family businesses make up a large percentage of SME worldwide, it would therefore be useful to replicate this study in other countries in an attempt to verify to what extent the factors influencing the success of copreneurial businesses in South Africa differ from those affecting these types of businesses abroad. The question of whether culture influences the success of these family businesses would also be worth pursuing. Specific attention should be given to black owned copreneurship. Future research could also investigate whether the perceptions of factors influencing the success of copreneurial businesses, differ between husbands and wives.

An interesting finding in the current study is that the growth and financial performance of the copreneurial business has no influence on whether the spouses are satisfied with their involvement in their copreneurial business or experience this involvement as beneficial to their marriage or personal development. These relationships should be subjected to further testing and investigation.

Despite the limitations identified, this study has added to the empirical body of family business research and has highlighted numerous opportunities for investigating teams within the context of the family business.

References

ADENDORFF, C.M. 2004. The development of a cultural family business model of good governance for Greek family businesses in South Africa, Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Grahamstown: Rhodes University. [ Links ]

ANCONA, D. & CALDWELL, D.F. 1992. Demography and design: predictors of new product team performance. In Beckman, C.M. & Burton, M.D. 2005. Founding the future: The evolution of top management teams from founding to IPO. [Online] Available at: http//web.mit.edu/burton/www/FoundingtheFuture.Final.April.2005 [Accessed 2007-05-22] [ Links ].

ARONOFF, C.E., ASTRACHAN, J.H., MENDOSA, D.S. & WARD, J.L. 1997. Making sibling teams work: the next generation. Family business leadership series, Georgia: Family Enterprise publishers. [ Links ]

ASTRACHAN, J.H. & ARONOFF, C.E. 1998. Succession issues can signal deeper problems, Nation's Business, May, 86(5):72-74. [ Links ]

ASTRACHAN, J.H. & KOLENKO, T.A. 1994. A neglected factor explaining family business success: human resource practices, Family Business Review, 7(3):251-262. [ Links ]

BARNETT, F. & BARNETT, S. 1988 Working together: Entrepreneurial couples, Berkeley, Calif: Ten Speed Press. [ Links ]

BARRICK, R.B., STEWART, G.L., NEUBERT, M.J. & MOUNT, M.K. 1998. Relating member ability and personality to work-team processes and team effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(3):377-391. [ Links ]

CAMPBELL, A. 2008. Tips for incubating your small business idea while still working full-time. AW Career and Biz Blog, [Online] Available at: http://www.advancingwomen.com/wordpress/?p=407 [Accessed 2008-10-06] [ Links ].

CAMPION, M.A., PAPPER, E.A. & MEDSKER, G.J. 1996 Relations between work team characteristics and effectiveness: a replication and extension. Personnel Psychology, 49:429-432. [ Links ]

CAMPION, MA, MEDSKER, G.J. & HIGGS, A.C. 1993. Relations between work group characteristics and effectiveness: Implications for designing effective work groups. Personnel Psychology, 46:823-850. [ Links ]

CHARLES, J. 2008. Top secrets of successful couplepreneurs. Biznik, [Online] Available at: http://biznik.com/articles/top-secrets-of-successful-couplepreneurs [Accessed 2008-10-06] [ Links ].

COLE, P.M. & JOHNSON, K. 2007. An exploration of successful copreneurial relationships postdivorce. Family Business Review, 20(3):185-198. [ Links ]

COOPER, D.R. & SCHINDLER, P.S. 2007. Business research methods (9th ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

COWIE, L. 2007. An investigation into the components impacting the effective functioning of management teams in small businesses, Unpublished Honours Treatise. Port Elizabeth: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. [ Links ]

DANES, S.M. & OLSON, P.D. 2003. Women's role involvement in family businesses, business tensions, and business success. Family Business Review, 16(1):53-68. [ Links ]

DANES, S.M., ZUIKER, V, KEAN., R. & ARBUTHNOT J. 1999. Predictors of family business tensions and goal achievement, Family Business Review, 12(3):241-252. [ Links ]

DOOLEN, T.L., HACKER, M.E. & VAN AKEN, E. 2006. Managing organizational context for engineering team effectiveness. Team Performance Management, 12(5/6):11. [ Links ]

FARRINGTON, S.M. 2009. Sibling partnerships in South Arican small and medium-sized family businesses, Unpublished doctoral thesis, Nelson Mandela Metroplitan University, Port Elizabeth.

FITZGERALD, M.A. & MUSKE, G. 2002. Copreneurs: an exploration and comparison to other family businesses. Family Business Review, 15(1):1-16. [ Links ]

GAGE, D., GROMALA, J. & KOPF, E. 2004. Successor partners: gifting or transferring a business or real property to the next generation. ACTEC Journal, 30(3):193-197. [ Links ]

GALE, T. 2002. Entrepreneurial couples. Encyclopaedia of Small Business, [Online] Available at: http://www.accessmylibrary.com/coms2/summary_0193-12289_ITM [Accessed 2008-10-01] [ Links ].

GERSICK, K.E., DAVIS, J.A., MCCOLLOM HAMPTON, M.M. & LANSBERG, I. 1997. Generation to generation – life cycles of the family business, Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

GLADSTEIN, D.L. 1984. Groups in context: a model of task group effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29:499-517. [ Links ]

GOLDBERG, S.D. 1996. Research note: effective successors in family-owned businesses: significant elements. Family Business Review, 9(2):185-197. [ Links ]

GOVERNANCE FOR THE FAMILY BUSINESS (KPMG). 2008. KPMG.ca, [Online] Available at: http://www.kpmg.ca/en/services/enterprise/issuesGrowthGovernance.html [Accessed 2008-09-18] [ Links ].

GROESBECK, R. & VAN AKEN, E.M. 2001. Enabling team wellness: monitoring and maintaining teams after start-up. Team Performance Management, 7(1/2):11-20. [ Links ]

GUZZO, R.A. & DICKSON, M.D. 1996. Teams in organizations: Recent research on performance and effectiveness. Annu. Rev. Psychol, 47:307-338. [ Links ]

GUZZO, R.A. & DICKSON, M.D. 1996. Teams in organizations: Recent research on performance and effectiveness. Annual Review Psychology, 47:307-338. [ Links ]

HACKMAN, J.R. 1987. The design of work teams. In Campion, M.A., Medsker, G.J. & Higgs, A.C. (1993) Relations between work group characteristics and effectiveness: Implications for designing effective work groups. Personnel Psychology, 46:823-850. [ Links ]

HACKMAN, J.R. 1990. Creating more effective work groups in organizations. In Howard, L.W., Foster, S.T. & Shannon, P. 2005. Leadership, perceived team climate and process improvement in municipal government. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 22(8):769-795. [ Links ]

HAIR, J.F., ANDERSON, R.E., TATHAM, R.L. & BLACK, W.C. 1998. Multivariate data analysis, (5th ed.) Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

HAIR, J.F., BLACK, W.C., BABIN, J.B., ANDERSON, R.E. & TATHAM, R.L. 2006. Multivariate data analysis, (6th ed.) Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson/Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

HANDLER, W.C. 1991. Key interpersonal relationships of next-generation family members in family firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 29(3):21-32. [ Links ]

HAUSER, B. 2004. Family governance in 2004: Parallels from world politics and corporate boardrooms. The Journal of Wealth Management. Summer 2004. [Online] Available at: http://www.iijournals.com/JPPM/default.asp?Page=2&ISS=10261&SID=412355 [Accessed. 2008-10-18].

HELLRIEGEL, D., JACKSON, S.E., SLOCUM, J., STAUDE, G., AMOS, T., KLOPPER, H.B., LOUW, L. & OOSTHUIZEN, T. 2004. Management, (2nd SA ed.) Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

HITT, M.A., MILLER, C.C., & COLELLA, A. 2006. Organisational behavior: A systematic approach, New York: John Wiley. [ Links ]

HOFSTRAND, D. 2000. Designing family business teams. Ag decision maker, October. Iowa State University, Iowa. [ Links ]

HOWARD, L.W., FOSTER, S.T. & SHANNON, P. 2005. Leadership, perceived team climate and process improvement in municipal government. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 22(8):769-795. [ Links ]

HUSBANDS, WIVES AND BUSINESS. 2008. Small business solutions, New York Life. [Online] Available at : http://www.newyorklife.com/cda/0,3254,13979,00.html [Accessed 2008-10-01] [ Links ].

HYATT, D.E. & RUDDY, T.M. 1997. An examination of the relationship between work group characteristics and performance: once more into the breech. Personnel Psychology, 50:553-585. [ Links ]

IVANCEVICH, J., KONOPASKE, I. & MATTESON, M. 2005. Organisational behavior and management (7th ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. [ Links ]

JAFFE, D. 1990. Working with the ones you love: conflict resolution and problem solving strategies for successful family business, Berkeley, CA: Conari Press. [ Links ]

KECK, S. 1997. Top management team structure: Differential effects by environmental context. In Beckman, C.M. & Burton, M.D. 2005. Founding the future: The evolution of top management teams from founding to IPO. [Online] Available at: http//web.mit.edu/burton/www/FoundingtheFuture.Final.April.2005 [Accessed 2007-05-22] [ Links ].

KEEN, T.R. 2003. Creating effective and successful teams, United States of America: Purdue University Press. [ Links ]

KOZLOWSKI, S.W.J. & ILGEN, D.R. 2006. Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7(3):77-124. [ Links ]

KREITNER, R. & KINICKI, A. 1995. Organisational behaviour (3rd ed.) Chicargo: Irwin. [ Links ]

LANSBERG, I. 1999. Succeeding generations: realising the dreams of families in business. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

LANSBERG, I. 2001. When compensation divides siblings. Family Business Magazine, [Online] Available at: http://www.library.familybusinessmagazine.com/issues/Spring2001/compensati3527.shtml [Accessed 2006-02-28] [ Links ].

MARSHACK, K. 1994. Love and work: how co-entrepreneurial couples manage the boundaries and transitions in personal relationships and business partnerships, Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Santa Barbara, CA: Fielding Institute. [ Links ]

MARSHACK, K.J. 1993. Coentrepreneurial couples: A literature review on boundaries and transitions among copreneurs. Family Business Review, 6(4):355-369. [ Links ]

MARSHACK, K.J. 2002. Cultivating resilient leadership can help family business to succeed. Vancouver Business Journal Weekly, August 23. [ Links ]

MONDY, R.W. & PREMEAUX, S.R. 1995. Concepts, practices, and skills, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc. [ Links ]

MUSKE, G., & FITZGERALD, M.A. 2006. A panel of study of copreneurs in business: Who enters, continues, and exits?. Family Business Review, 19:193-206. [ Links ]

MUSTAKALLIO, M., AUTIO, E. & ZAHRA, A. 2002. Relational and contractual governance in family firms: effects on strategic decision making. Family Business Review, 15(3):205-222. [ Links ]

NELTON, S. 1986. In love and business: how entrepreneurial couples are changing the rules of business and marriage, Wiley: New York. [ Links ]

NORTHOUSE, P.G. 2004. Leadership: theory and practice (3rd ed.) United States of America: Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

NUNNALLY, J.C. & BERNSTEIN, I.H. 1994. Psychometric theory (3rd ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

O'CONNOR, V., HAMOUDA, A., MCKEON, H., HENRY, C. & JOHNSTON, K. 2006. A study of mixed gender founders of ICT companies in Ireland. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 13(4):600-619. [ Links ]

OLUKAYODE, A.A, & EHIGIE, B.O. 2005. Psychological diversity and team interaction processes: A study of oil-drilling work teams in Nigeria. Team Performance Management, 11(7/8):280-301. [ Links ]

PETERSON, R.A. 1994. A meta-analysis of Cronbach's co-efficient alpha. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(2):381-391. [ Links ]

POZA, E.J. & MESSER, T. 2001. Spousal leadership and continuity in the family firm. Family Business Review, 14:25-35. [ Links ]

RING, P.S., & VAN DE VEN, A.H. 1994. Developmental processes of cooperative interoganisational relationships. In Mustakallio, M., Autio, E. & Zahra, A. 2002. Relational and contractual governance in family firms: Effects on strategic decision making. Family Business Review, 15(3):205-222. [ Links ]

ROBBINS, S. P. 2003. Organisational behavior (10th ed.) United States of America: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

ROBIN, E. 2007. Wedded to the business. WomenEntrepreneur.com [Online] Available at: http://www.womenentrepreneur.com/article/2256.html [Accessed 2008-10-07] [ Links ].

ROBIN, E. 2008. What's the best way to partner with your spouse? Entrepreneur.com [Online] Available at: http://www.entrepreneur.com/ask/answer6768.html [Accessed 2008-09-02] [ Links ].

ROHA, R.R. & BLUM, A. 1990. Enterprising couples. Changing Times, 44(12). [ Links ]

ROURE, J. & KEELEY, R. 1990. Predictors of success in new technology based ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 5:201-220. [ Links ]

ROWE, B.R. & HONG, G. 2000. The role of wives in family businesses: the paid and unpaid work of women. Family Business Review, 13(1):1-13. [ Links ]

RUTHERFORD, M.W., MUSE, L.A. & OSWALD, S.L. 2006. A new perspective on the developmental model for family business. Family Business Review, 19(4):317-333. [ Links ]

SHARMA, P. 2004. An overview of the field of family business studies: current status and directions for the future. Family Business Review, 17(1):1-36. [ Links ]

SHEARD, A.G. & KAKABADSE, A.P. 2002. From loose groups to effective teams: The nine key factors of the team landscape. Journal of Management Development, 21(2):133-151. [ Links ]

SONFIELD, M.C. & LUSSIER, R.N. 2004. First-second and third-generation family firms: A comparison. Family Business Review, 17(3):189-202. [ Links ]

SORENSON, L.R. 2000. The contribution of leadership style and practices to family and business success. Family Business Review, 13(3):183-200. [ Links ]

TAGIURI, R. & DAVIS, J.A. 1992. On the goals of successful family companies. Family Business Review, 5(1):43-62. [ Links ]

TOMPSON, G.H. & TOMPSON, H.B. 2000. Determinants of successful copreneurship. ICSB World Conference, Brisbane, Australia, June:2-14. [ Links ]

VAN AUKEN, H. & WERBEL, J. 2006. Family dynamic and family business financial performance: spousal commitment. [Online] Available at: <http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118588516/abstract?CRETRY=1andSRETRY=0> [Accessed 2008-09-10] [ Links ].

VAN DER MERWE, S.P. & ELLIS, S. 2007. An exploratory study of some of the determinants of harmonious family relationships in small and medium-sized family businesses. Management Dynamics, 16(4):24-35. [ Links ]

VENTER, E. 2003. The succession process in small and medium-sized family businesses in South Africa, Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Port Elizabeth: University of Port Elizabeth (NMMU). [ Links ]

WARD, J.L. 2004 Perpetuating the family business. 50 lessons learned from long-lasting successful families in business, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

YANCEY, M. 1998. Work teams: Three models of effectiveness. [Online] Available at: http://www.workteams.unt.edu/literature/paper-myancey.html [Accessed 2007-05-10] [ Links ].

Accepted October 2009

Appendix