Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

versão On-line ISSN 2222-3436

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.13 no.4 Pretoria Jan. 2010

ARTICLES

Shareholders' corporate environmental

Charl de VilliersI; Chris van StadenII

IDepartment of Accounting and Finance, University of Auckland Business School and Department of Financial Accounting, University of Pretoria

IIDepartment of Accounting and Information Systems, University of Canterbury

ABSTRACT

We do a survey of individual shareholders' corporate environmental disclosure needs. We find that South African individual shareholders require companies to disclose the following specific environmental information: environmental risks and impacts, environmental policy, measurable environmental targets, performance against targets, environmental costs disclosed separately, and an independent environmental audit report.

Respondents prefer this information in a separate section of the annual report and on company websites. Individual shareholders want such disclosure to be prescribed by law and/or stock exchange rules. The most popular reason why they want environmental information disclosed is to hold companies accountable for their environmental stewardship. A high percentage of individual shareholders also indicate that they want disclosure because they are concerned about climate change. These findings imply that legislators and standard setters may have to consider changing disclosure laws and standards.

JEL D12, 84

1 Introduction

The natural environment, and specifically climate change, have been in the spotlight lately. A growing consensus holds that human activities are causing climate change. Since companies provide a large proportion of goods and services in the South African economy, it stands to reason that companies at least contribute to climate change. However, it is hard for outsiders to know how corporate activities influence the environment, unless the information is made available by the companies themselves. Environmental disclosures are made by many companies, but it is mostly done on a voluntary basis and it has been described as piecemeal and unreliable (Deegan & Rankin, 1996; Laufer, 2003). Early shareholder surveys (1970s and 1980s) show no enthusiasm for environmental information (see our discussion in the next section). Therefore, it is unclear whether shareholders would be interested in this information, which is in addition to the normal financial information mandated by generally accepted accounting practice. However, given the increasing importance of environmental issues, we are interested whether shareholders now require environmental information, presented more reliably, from their companies.

Research on the information needs of shareholders as users of environmental information has been limited (Solomon & Solomon, 2006). The only South African surveys to include feedback from individual shareholders date back more than a decade (De Villiers &Vorster, 1995; and De Villiers, 1998). However, the responses of shareholders were not reported separately in these surveys, but with other information users. Stainbank and Peebles (2006) survey institutional investors about annual report usefulness and include a question on environmental reporting. Although institutional investors and individual shareholders may share similar (wealth maximisation) goals, individual shareholders can only rely on publicly available information, whereas institutional investors have the means to also gather additional private information. The information needs of institutional investors have been examined (e.g. Solomon & Solomon, 2006), but individual investors' information needs have not been examined comprehensively and important issues were therefore overlooked.

Our research aims to fill this gap in the literature. Our general research focus is the interest of individual shareholders in aspects of the disclosure of environmental information. The research questions that we address in this study are whether individual shareholders want corporate environmental disclosure (see Table 2, Panel A), which types they want (Panel A), where they want it disclosed (Panel B), whether they want it made compulsory (Panel C), why they want the information (Panel D), and what they would use it for (Table 3).

The rest of the paper is organised in sections. We first do a literature review. Next, we provide theoretical perspectives. The method is then followed by results, and finally, a discussion and conclusion.

2 Literature review

Much research is done on environmental disclosure patterns (Al-Tuwaijri, Christensen & Hughes, 2004; Cho & Patten, 2007; De Villiers & Van Staden, 2006; Deegan & Rankin, 1996; Gray, Kouhy & Lavers, 1995; Magnes, 2006; Parker, 2005; Patten, 2002; Neu, Warsame & Pedwell, 1998; Gray, Owen & Adams, 1996), but few ask users of such information what they need. From the limited research in this area, it is clear that analysts and institutional investors do not ask for environmental disclosure (see literature reviews by Milne & Chan, 1999; and Solomon & Solomon, 2006) but studies using an experimental design have shown that both institutional investors and individual shareholders use environmental information in investment decision-making when this is provided (see for example Chan & Milne, 1999; and Milne & Chan, 1999). The experiments require participants to make an investment decision, so they do not explore other reasons why users may want the information. Also, they do not explore whether individuals would seek environmental information if it was not provided. Surveys may answer these questions.

The early shareholder surveys (1970s and 1980s) (reviewed by Milne & Chan, 1999; and Solomon & Solomon, 2006) show no enthusiasm for environmental information and none ask why investors may want it or what they would use it for. Later studies (1990s) (see for example Epstein & Freedman, 1994; and Deegan & Rankin, 1997; De Villiers, 1998) show that individual investors want environmental information, but the surveys don't ask why the information is needed and what it would be used for. There appears to be no surveys of individual investors after 1997 and no surveys of users (including shareholders) in South Africa after 1998.

In the US shareholders indicated that they regard the financial (economic) result of environmental disclosure as very important (Epstein & Freedman, 1994). An independent audit was favoured by 68 per cent and the annual report was favoured as disclosure medium by 82 per cent. The survey did not ask shareholders about other disclosure media or why they wanted/needed environmental information, or what they would use it for.

In Australia, 72 per cent of shareholders regarded environmental information as material (Deegan & Rankin, 1997). The authors of the study used the level of materiality to imply that the information will be used for the purpose of investment decision-making. Shareholders were not asked why they wanted or needed the information or if they had other uses for the information. The questionnaire only asked about annual report disclosure and 73 per cent of shareholders wanted environmental information disclosed there. Shareholder views were that government should mandate environmental reporting guidelines, rather than the accounting profession doing so.

In South Africa, De Villiers and Vorster (1995) and De Villiers (1998) report surveys of auditors, managers and users of financial statements. In both studies, users are from different groups, including shareholders. However, it is not possible to separate the responses of the shareholders from those of other users. The results of both surveys indicate that users were in favour of environmental disclosures and specifically in De Villiers (1998) they wanted disclosure of an overview of risks and impacts (100 per cent), environmental policy (84 per cent), measurable targets (74 per cent), performance against targets (74 per cent), environmental costs (79 per cent), and an environmental audit (84 per cent). A high percentage (90 per cent) of users also wanted more environmental disclosure on a compulsory basis and 89 per cent want this information in annual reports. Neither of the two surveys asked about the preferred mechanism to make disclosure compulsory; asked about other disclosure media (such as separate environmental reports or websites); or asked why users would want or use environmental information.

Our survey, being one of the first to actually focus on individual shareholders, addresses, among other things, the following gaps in the literature as identified above:

- we ask why the information is needed and what it would be used for (Table 3);

- we ask about the disclosure media other than annual reports (Table 2, Panel B);

- we ask how environmental disclosure should be made compulsory (if at all) (Table 2, Panel C);

- we ask if the information should be audited (Table 2, Panel A, Question 6); and

- we explore the reasons for the disclosures (Table 2, Panel D).

3 Theoretical perspectives

In our survey, we ask shareholders about their information needs. Therefore, some of the theories customarily used in social and environmental accounting research, such as legitimacy, stakeholder and accountability theories, are not appropriate here, because they do not take a shareholder perspective. Therefore, we place our study within an agency theory framework, i.e. shareholders are the principals and managers the agents. Agents have more complete information than principals have, so principals need to manage the acquisition of information to protect their interests (Watts & Zimmerman, 1978). One of the ways in which the agency problem can be reduced is through the disclosure of relevant information to inform the principal of the agent's actions in order to reduce information asymmetry (Healy & Palepu, 2001). The flow of information is regulated by various mechanisms, such as company law, accounting standards and stock exchange rules. These rules are there to protect, among others, shareholders. The protection mechanisms evolve over time to provide greater protection in a changed environment. Conditions have to change before protection mechanisms (e.g. additional legislation) are updated creating a lag (Gray et al., 1997). We investigate whether conditions have changed and whether additional protection mechanisms need to be considered. Institutional investors sometimes have access to private information and have more resources to analyse investment opportunities. Therefore we ask the opinions of individual shareholders, as the group that can only rely on public information and that needs more protection against information asymmetry.

4 Method

4.1 Questionnaire development

The first six questions in our survey ask whether respondents want certain specific environmental items disclosed (see the first column of Table 2 for the questions). The questions start with general type of information and progress to more specific information and are based on De Villiers (1998). These questions are asked firstly to get separate answers from shareholders and secondly to get answers from a South African user group (of corporate information) for the first time in a decade. The rest of the survey consists of questions that the literature review indicated to be gaps in our knowledge. Accordingly, we ask where the information should be disclosed, providing additional media as options. Then, we explore various mechanisms for making corporate environ-mental disclosure compulsory, if shareholders want this. Next, we ask four questions regarding their reasons for wanting such disclosures. Each of these four questions reflects the philosophy behind one of four theories/perspectives often used in social and environmental research, namely agency (decision-usefulness), legitimacy, accountability and critical. Finally, for each of a range of specific environmental disclosures, we ask whether shareholders use/would use the information and for what purpose they use/would use it. We turned the survey into an electronic survey instrument with a database automatically capturing responses and the sequence of responses, but no identifying information on the respondents. Respondents could read the ethics clearance on the website and the survey instrument was hosted on a secure area of the university website. Nine academic colleagues checked the questionnaire for clarity and precision and gave comments.

4.2 Sample and respondents

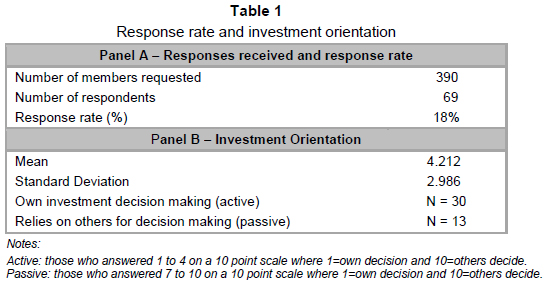

Since we wanted the survey to be completely anonymous, we asked the chairman of the South African Shareholders' Association to email members with a request to click on the Url-link provided in the email message and to complete the web-based survey anonymously. This implies that only members who have email were included. Normally, individuals with access to email are seen as more sophisticated than those who do not. However, in this case, we do not believe that this impacted on our results, because we believe all shareholders to be relatively sophisticated. The survey was designed to be short and would have taken 5-10 minutes to complete. The request was sent to a random sample of 390 members with a follow-up request two weeks later and we received 69 usable responses (29 after the follow-up request) for an 18 per cent response rate (see Table 1 Panel A). This response rate appears favourable compared to that in other studies: De Villiers and Vorster (1995) 7.3 per cent, Deegan and Rankin (1997) 24 per cent, Widener (2007) 12.5 per cent, and Abdel-Kader and Luther (2008) 19.6 per cent.

We ask respondents to categorise their investment orientation on a 10 point scale where 1 represents someone who makes all their own investment decisions completely independently and 10 represents someone who relies totally on others to make decisions for them. We expected that most respondents would tend towards making their own decisions, because they belonged to a shareholders' association. Table 1 Panel B shows the mean for this question to 4.212 (with a standard deviation of 2.986) which place respondents towards the own decision making (active) part of the range. We classify those who answered from 1 to 4 as "active" investors and those who answered from 7 to 10 as "passive" investors. Thirty (30) respondents were active and 13 passive investors. This confirms our expectation that there would be a larger percentage of active investors. It also provides evidence that our respondents are diverse and this is important if the findings are to be generalised to the South African individual shareholder. While our results are representative of the views of shareholders belonging to the South African Shareholders' Association, care should be taken in generalising it to the South African individual shareholder population. However, the profile of members of the South African shareholder association (being generally males, over 50 and retired) seems to fit anecdotal evidence of the general profile of individual shareholders in South Africa.

We minimise the possibility of a non-response bias by making it easy for respondents who are less positive to answer (they could click through and the survey only took 5-10 minutes to complete), by making it anonymous (respondents knew that we would not know who answered) and by asking the chairman to send out the request under his own name (making it more official). We regard early respondents (the first 30) as representative of those who are positive about corporate environmental disclosures and late respondents (the last 29 after the follow-up request) as representative of those who are less positive about the subject and those who did not answer the questionnaire and compare the responses of early and late respondents. We acknowledge that this kind of test is not conclusive in ruling out a non-response bias, however it is accepted practice and used for this purpose in surveys (see for example, Oppenheim, 1992; Pike, 1996; Deegan & Rankin, 1997; Guilding, Cravens & Tayles, 2000). We compared the mean scores (calculated by weighing the responses on the 5 point Likert scale from 1-5) for these two groups for each of the main questions in the survey by way of an independent t-test (two tailed). We found only one significant difference (at the 10 per cent level), namely that late respondents were more positive about separate environmental reports than early respondents were. This difference is not important to our findings, because there were other reporting media that respondents favoured above separate reports. With only this one significant difference, and bearing in mind that the late respondents (representative of non-respondents) were more positive than the early respondents were, we believe that the risk of a non-response bias in the results is adequately addressed.

5 Results

The main results of the survey are reported in Table 2 with the questions in the first column, the percentage of respondents who agreed or strongly agreed in the second and the mean in the third. The standard deviation is reported in the last column. A 5-point Likert scale was used. For the purpose of calculating the mean and the standard deviation, the following weightings were used: Strongly agree=1, agree=2, neutral=3, disagree=4, and strongly disagree=5. Therefore, the closer the mean is to one, the more respondents agreed with the question, whereas a mean of 3 indicates neutrality. Overall, respondents appear to be very positive about corporate environmental disclosure. It is also worth noting that the standard deviation is mostly under 1, indicating a fair amount of agreement among respondents, as responses were generally not far from the mean.

At least 75 per cent of respondents wanted each of the specific types of environmental information in the first 6 questions disclosed (see Table 2, Panel A). We reiterate these in the conclusion.

The disclosure medium that most respondents prefer, is the annual report (90 per cent), followed by the company website (82 per cent) (see Panel B). Separate environmental reports (62 per cent) appear to be less popular. Within the annual report, respondents prefer environmental information to be disclosed in an environmental section (77 per cent). The chairman's report (70 per cent) was also a popular choice for environmental information in the annual report.

About two thirds of respondents indicated a preference for environmental disclosures to be made compulsory by legal means and/or stock exchange rules (see Panel C). Only 44 per cent favoured accounting standards as a means of making it compulsory. However, 81 per cent of respondents want environmental disclosures to be made compulsory in at least one of the ways mentioned. Only 10 per cent specifically indicated that they did not want environmental disclosures to be made compulsory.

We asked respondents to indicate why they want the information. In Panel D the result of this question is analysed. We were surprised to see that most respondents (94%) wanted the information for accountability from companies for their environmental stewardship and that 84 per cent gave concerns about climate change as a reason. We note that 79 per cent wanted it to allow companies to defend their environmental management (legitimating reasons). Although most of our respondents can be classified as active investors (making their own investment decisions), making investment decisions was the least popular reason (at 61 per cent) for requiring environmental disclosure. Following our agency expectations it would appear that accountability by the agent is the most important part for wanting this information. This is also reflected by the high percentage (75 per cent) of respondents that wanted the information independently audited. Shareholders already get the financial information in the financial statements and, therefore, they saw the role of the additional environmental information as discharging of accountability.

These questions dealt with reasons for wanting environmental disclosure in general. We also asked respondents about the use of specific environmental disclosure types. In this part of the survey we asked respondents to select the types of disclosure that they use/would use if it was given from a list that we provided and then to indicate what they would use it for. The most popular disclosures (support from 25 per cent or more of respondents) are given in Table 3

In Table 3 we report the most popular types of disclosure wanted in the survey. We show the types of information our respondents wanted, and what such information would be used for. In the survey we proposed three categories of uses for such environmental disclosures: for making investment decisions, for holding the company accountable, and for own interest (meaning that this is just considered interesting information).

As a final test, we compared the means of the responses of the active and passive investors in our sample using an independent samples t-test (two-tailed) and found few significant differences. This result may be influenced by the fact that we classified only 13 respondents as passive investors. The significant differences indicated that passive investors (those who rely more on others to make investment decisions) were more positive than active investors about the following:

- Disclosure of the environmental policy (significant at the 10 per cent level),

- Disclosure of environmental performance against targets (10 per cent),

- The annual report as disclosure medium (1 per cent),

- Using the Chairman's report within the annual report (5 per cent), and

- Companies to defend their environmental management (accountability) as a reason for disclosure (1 per cent).

Regardless of these differences between active and passive investors, both groups are positively disposed towards the compulsory disclosure of audited environmental information in annual reports and on websites for reasons of decision-usefulness and accountability.

6 Discussion and conclusions

Our survey results show that South African individual shareholders are very positive about the disclosure of a range of environmental information items including:

- overview of environmental risks and impacts,

- environmental policy,

- measurable environmental targets,

- performance against targets, and

- environmental costs disclosed separately.

This confirms our agency-derived expecta-tion that shareholders need this information to reduce information asymmetry. More importantly, there is evidence that shareholders are using specific information, or are planning to use it, something that has not been reported in the literature before. Our results therefore show definite enthusiasm in shareholder preferences for and uses of this information.

Shareholders also require the information to be audited, indicating that they need some assurance in order to improve the reliability of the information. Recent studies have shown that the level of assurance of environmental reports are low overall (Kolk & Perego, 2010), while a survey by KPMG (2008) shows that only 36 per cent of environmental reports in South Africa include assurance statements. Our finding that 75 per cent of South African shareholders want the information to be audited, indicates an important area that needs attention from companies and assurance providers, such as the accounting profession.

Our respondents want companies to disclose environmental information in a separate section of the annual report and on company websites. They are less enthusiastic about separate reports, presumably because they can get the separate reports on websites. Our respondents (81 per cent) wanted the disclosures to be regulated, which would increase the reliability of the information (as would assurance). We have indicated earlier that the flow of information could be regulated by various mechanisms, such as company law, accounting standards or stock exchange rules, or be left as discretionary and determined by market forces. Our respondents clearly preferred company law and/or stock exchange rules. The low percentage that preferred accounting standards as a way of regulation is interesting considering South Africa's long history of accounting standard setting. This could be a reaction against the current position of accepting international standards (i.e. they prefer a South African solution in the form of stock exchange rules or company law).

A most interesting finding is that more of our respondents wanted environmental infor-mation disclosed to hold companies accountable for their environmental stewardship than for investment decision making. Bear in mind that respondents could (and many did) choose both reasons. However, accountability is an important part of the agency relationship that we base our expectations on and therefore fits our theoretical framework. However, this conception of accountability is different from the stakeholder viewpoint taken in much of the accounting literature. In addition we find that many respondents (84%) also indicate that they want disclosure because they are concerned about climate change. This appears to be a more personal reason and an indication of strong environmental attitudes among individual shareholders.

Respondents also indicated that they use different types of environmental information for different purposes. This seems logical but has not been empirically tested before.

For example, environmental nrisks/impacts and environmental policy is mostly used for investment decision-making purposes (decision usefulness) while accountability is mostly cited for environmental audits.

In conclusion, the findings imply that regulators, legislators and standard setters may have to consider changing disclosure requirements, laws and standards and assurance providers may consider pursuing the market of assuring environmental reports.

Limitations

While our results are representative of the views of shareholders belonging to the South African Shareholders' Association, care should be taken in generalising to the South African individual shareholder population.

References

ABDEL-KADER, M. & LUTHER, R. 2008. The impact of firm characteristics on management accounting practices: a UK-based empirical analysis. The British Accounting Review, 40(1):2-27. [ Links ]

AL-TUWAIJRI, S.A., CHRISTENSEN, T.E. & HUGHES, K.E. 2004. The relations among environmental disclosure, environmental performance, and economic performance: a simultaneous equations approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(5-6):447-471. [ Links ]

CHAN, C.C. & MILNE, M. 1999. Investor reactions to corporate environmental saints and sinners: an experimental analysis. Accounting and Business Research, 29(4):250-272. [ Links ]

CHO, C.H. & PATTEN, D.M. 2007. The role of environmental disclosures as tools of legitimacy: a research note. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(7-8):639-647. [ Links ]

DE VILLIERS, C. 1998. The willingness of South Africans to support more green reporting. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 1(1):145-167. [ Links ]

DE VILLIERS, C. & VAN STADEN, C.J. 2006. Can less environmental disclosure have a legitimising effect? Evidence from Africa. Accounting Organizations and Society, 31(8):763-781. [ Links ]

DE VILLIERS, C. & VORSTER, Q. 1995. More corporate environmental reporting in South Africa?. Meditari Accountancy Research, 3(1):44-66. [ Links ]

DEEGAN, C. & RANKIN, M. 1996. Do Australian companies report environmental news objectively? An analysis of environmental disclosures by firms prosecuted successfully by the environmental protection authority. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 9(2):50-67. [ Links ]

DEEGAN, C. & RANKIN, M. 1997. The materiality of environmental information to users of annual reports. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 10(4):562-583. [ Links ]

EPSTEIN, M.J. & FREEDMAN, M. 1994. Social disclosure and the individual investor. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 7(4):94-109. [ Links ]

GRAY, R., KOUHY, R. & LAVERS, S. 1995. Corporate social and environmental reporting: a review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 8(2): 47-77. [ Links ]

GRAY, R., OWEN, D. & ADAMS, C. 1996. Accounting and accountability: Changes and challenges in corporate social and environmental reporting. Prentice Hall: London. [ Links ]

GRAY, R., DEY, C., OWEN, D., EVANS, R. & ZADEK, S. 1997. Struggling with the praxis of social accounting: Stakeholders, accountability, audits and procedures. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 10:325-364. [ Links ]

GUILDING, C., CRAVENS, K.S. & TAYLES, M. 2000. An international comparison of strategic management accounting practices. Management Accounting Research, 11(1):113-135. [ Links ]

HEALY, P.M. & PALEPU, K.G. 2001. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31(1-3): 405-440. [ Links ]

KOLK, A. & PEREGO, P. 2010. Determinants of the adoption of sustainability assurance statements: An international investigation. Business Strategy and the Environment, 19(3):182-198. [ Links ]

KPMG. 2008. KPMG International survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2008. October 2008 KPMG International. [Online], available at: http://www.kpmg.com/Global/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesAndPublications/ Pages/Sustainability-corporate-responsibility-reporting-2008.aspx [Accessed during 2009] [ Links ].

LAUFER, W.S. 2003. Social accountability and corporate greenwashing. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(3): 253-261. [ Links ]

MAGNES, V. 2006. Strategic posture, financial performance and environmental disclosure: an empirical test of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 19:540-563. [ Links ]

MILNE, M. & CHAN, C. 1999. Narrative social disclosures: how much of a difference do they make to investor decision-making. British Accounting Review, 31(4):439-457. [ Links ]

NEU, D., WARSAME, H. & PEDWELL, K. 1998. Managing public impressions: environmental disclosures in annual reports. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 23(3):265-282. [ Links ]

OPPENHEIM, A.N. 1992. Questionnaire Design, Interviewing and Attitude Measurement. Pinter Publishers: London. [ Links ]

PARKER, L.D. 2005. Social and environmental accountability research: a view from the commentary box. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 18:842-860. [ Links ]

PATTEN, D.M. 2002. The relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: a research note. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 27(8):763-773. [ Links ]

PIKE, R. 1996. A longitudinal survey on capital budgeting practices. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 23(1):79-92. [ Links ]

SOLOMON, J.F. & SOLOMON, A. 2006. Private social, ethical and environmental disclosure. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 19(4):564-591. [ Links ]

STAINBANK, L. & PEEBLES, C. 2006. The usefulness of corporate annual reports in South Africa: Perceptions of preparers and users. Meditari Accountancy Research, 14(1):69-80. [ Links ]

WATTS, R. & ZIMMERMAN, J.L. 1978. Towards a positive theory of the determination of accounting standards. The Accounting Review, 53(1):112-134. [ Links ]

WIDENER, S.K. 2007. An empirical analysis of the levers of control framework. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(7-8):757-788. [ Links ]

Accepted July 2010