Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Educational Research for Social Change

versión On-line ISSN 2221-4070

Educ. res. soc. change vol.12 no.2 Port Elizabeth oct. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2023/v12i2a6

ARTICLE

Leading for Sustainability and Empowerment: Reflecting on the Power of Collaboration and Humanising Pedagogy

Heloise SathorarI; Deidre GeduldII; Muki MoengIII; Tobeka MapasaIV; Helena OosthuizenV

INelson Mandela University. Heloise.Sathorar@mandela.ac.za; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4947-0885

IINelson Mandela University. Deidre.Geduld@mandela.ac.za; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6175-0508

IIINelson Mandela University. Muki.Moeng@mandela.ac.za; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9805-766x

IVNelson Mandela University. Tobeka.Mapasa@mandela.ac.za; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0834-9341

VNelson Mandela University. Helena.Oosthuizen@mandela.ac.za; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9440-9170

ABSTRACT

The Covid-19 pandemic caused great distress in the higher education sector, globally. Higher education institutions had to adapt from presenting in-person classes to online remote learning, bringing with this several challenges of increased workloads, feelings of loss, grief, and being overwhelmed for both students and academic staff. Leading in times of crisis is not easy. It is even more difficult for women leaders who must deal with the historical impact of gender inequality in the workplace as well as the stereotypical views of the role of women. In this paper, five women academics who also hold leadership positions in the faculty of education at Nelson Mandela University reflect on their experience of leading their respective teams through the Covid-19 pandemic. Researchers have postulated that women in strategic leadership positions would better understand work policy obstacles owing to their knowledge of such barriers, as well as advancing the educational outcomes for all stakeholders in higher education. As women in leadership, we reflect on how collaboration assisted us to empower each other as well as our respective teams. The characteristics of democratic leadership guided this inquest. A critical paradigm and humanising pedagogy principles were used to frame the study, which enabled us to draw on our lived experiences and to engage in dialogue in order to make sense of the process of empowerment for sustainability. We engaged in collaborative self-study and used narrative freewriting to generate data. In addition, use was made of a thematic analysis to reduce the data and identify common themes. The findings of the study question whether current leadership practices contribute to equality in the workplace, support collaboration, and encourage self-care and empowerment. The study proposes a humanising leadership model to enhance leadership practices.

Keywords: democratic leadership, humanising pedagogy, collaboration, critical theory

Introduction and Background

It is well argued in literature that higher education institutions have a significant role to play in the evolution of society because they educate and train future leaders, workers, and citizens (Teague, 2015). One aspect of advancing society is to ensure that it is sustainable, which requires a strong higher education system. Amongst many others, higher education is currently faced with leadership challenges. Moodly and Toni (2017) contended that for higher education to be sustainable, its leadership needs to be reimagined. Seale et al. (2021) suggested that women leaders are the answer to the leadership crisis faced by higher education. The latter authors argued that women can shift existing patriarchal hegemonies to create a pluralistic leadership culture that encourages transformational leadership to flourish.

Moodly and Toni (2017) contended that women are more likely to adopt a more collaborative, cooperative and democratic leadership style. Raelin (2012) advanced that such leadership requires power to be shared, and encourages reflection-in-action. He further argued that it occurs beyond hierarchical roles and positions and requires genuine participation in leadership and in decision-making at all levels and in different processes. Therefore, fundamental to collaborative leadership are the principles of mutual respect, trust, non-judgemental inquiry, sharing of information, and critical scrutiny of others (Terzi & Derin, 2016).

Higher education has seen its fair share of challenges in the past two decades. Constant changes such as the continuing decrease in subsidies, mergers and incorporations, a rise in student numbers, the #FeesMustFall movement, calls for decolonisation, as well as Covid-19 have required a special kind of leadership to ensure higher education sustainability. Governments and institutions globally, have recognised that coordination and collaboration are the only way to deal with these challenges effectively. Reflecting on the challenges of Covid-19, Shingler-Nace (2020) argued that authenticity and foundational concepts can assist in the most complex and complicated situations. One of the basic foundations she shared from her lessons learnt is collaboration. She further argued that a fully committed team, with members who lean on one another and can be depended on, empower each other to recognise when they need to hand over to the next leader in order to minimise burnout.

Lawton-Misra (2019) argued that during the #FeesMustFall protests, leaders were thrust into roles to which they had never before been exposed, and that they needed to make every effort to find ways to navigate and respond to students' demands. In their study of women deputy vice-chancellors, Moodly and Toni (2017) argued that re-imagining leadership forms part of the decolonisation process. They found that women leaders displayed inclusive, caring, cooperative, and service-oriented qualities that would put them in a better position to lead during turbulent times.

Traditionally, leadership implies a relationship of power to guide others. Recently, focus has moved from power to empowerment with leaders transferring power to their teams through collaboration (Raelin, 2012). Moreover, the main features of leadership models have evolved from authoritarian to collaborative and participatory leadership styles (Terzi & Derin, 2016). This shift in leadership styles has coincided with more women taking up senior leadership and management positions in institutions, including universities (Seale et al., 2021).

In this paper, five women academics who all hold leadership positions in the faculty of education at Nelson Mandela University reflect on how collaboration and a humanising pedagogy assisted them not only to fulfil their respective roles but also to empower their respective teams. A humanising pedagogy is based on the idea that humans are driven by a need to reason and participate in decision making regarding their lives (Freire, 1970). In this qualitative study, we engaged in collaborative self-study as well as narrative freewriting to generate data. The data were reduced through thematic analysis, which assisted in identifying common themes. The findings of the study aim to encourage leaders in education to question whether current leadership practices contribute to equality in education, support sustainable work practices, and encourage self-care.

Humanising Pedagogy and Collaborative Teaming

This study resides in a critical paradigm and utilises humanising pedagogy principles as well as the advantages of collaborative teaming to frame the study, and draws on critical theory to "take cognisance of the subjectivity of individuals and their experiences in a complex world where not all experiences can be explained by logic" (Foley et al., 2015, p. 113). Similarly, McKernan (2013) explicated that criticality is more than understanding a specific situation; it involves finding ways to change oppressive situations to liberate people. According to Sathorar (2018), critical theory questions and investigates the subjective curriculum of everyday life (Apple, 2004). It interrogates the power structures that manipulate and influence rationality and truth (Foucault, 1984; Giroux, 2007) and challenges how subjectivity becomes a political ontology (Foucault, 1984; Giroux, 2007). Thus, critical theorists agree that humans construct their understanding of reality and the world they live in through the relationships and collaborations they have with other human beings (Foley et al., 2015).

In this paper, we reflect upon our lived experience of leadership, the development of agency through a critical look at our world of work, which takes place in collaboration with others, and seek to transform our working environment through active participation in democratic imperatives. We postulate that leadership is dependent on relationships and that applying humanising pedagogy principles would enhance leadership practices. Humanising pedagogy can be described as teaching practices that intentionally utilise the histories of our students, recognising the importance of their life experiences and background knowledge (Geduld & Sathorar, 2016). Freire's (1970) ideas about liberatory education respect and employ students' lived realities. We acknowledge the realities of our students as an integral part of educational practice and cast them as critically engaged, active participants in the co-construction of knowledge (Del Carmen Salazar, 2013; Geduld & Sathorar, 2016). We believe that when one leads, one also educates-and this serves as justification for applying humanising pedagogy principles to our leadership practices.

Humanising pedagogy enables us to draw on the lived experiences of staff members and to engage them in collective decision making in our respective departments in the faculty. Humanisation is closely linked to collaboration. Freire (1970) suggested that true dialogue that takes place under conditions of deep love for the world and humankind, humbleness towards each other, reciprocated trust amongst dialoguers, and the ability to think critically would assist in changing the world into a humanised place. Thus, leading in a humanised way requires collaboration through dialogue. A humanising perspective of collaborative leadership teams starts from the supposition that leaders are fully human; they resist the dehumanising efforts of leadership approaches that deny them and their teams a sense of interest and the opportunity to question the world critically (Freire, 1970). A humanising perspective acknowledges that critical consciousness is ever changing. This supports the idea that leaders are not infallible and that they require intellectual growth in various areas. Nowell et al. (2020) referred to four advantages of collaborative teams that support a humanising approach to leadership, namely, (1) promoting individual dignity, equality, uniqueness, and capacity to grow, (2) showing respect for the individual, (3) fostering an ethics of care, and (4) having a concern for the common good.

Dignity is premised on respect for and from others and, explicitly, mutual respect. Dignity is demonstrated by combining competence with compassion and decisive actions whilst strengthening capacity on the one hand and attending to the needs of vulnerable groups on the other (Khilji, 2021). It is an interpersonal act respected by all stakeholders who engage with each other in a fair, democratic, and honourable way that supports instinctive values and rights. Such an inclusive interpretation of dignity supports an interactive and interpersonal understanding of leadership (Khilji, 2021; Nowell et al., 2020).

Respect is an outflow of acknowledging the importance of human dignity. Respecting and valuing the opinions of others are key requirements for true dialogue and collaboration, which, in turn, are central to humanisation (Freire, 1970). The ethics of care signifies assenting values related to a commitment by the individual to render a service to those in need. To lead is to serve and to serve in a way that will make a change in the lives of others. This demonstration of compassion is necessary for human flourishment and fulfilment (Khilji, 2021). Finally, concern for the common good is demonstrated through the interconnectedness of individuals within a community of practice (Del Carmen Salazar, 2013). Communities of practice are driven by a common interest, and members are responsible for working towards a common goal as well as ensuring the collective growth and development of all.

In this paper, we advocate for a review of leadership practices and suggest that there is a need for humanising leadership principles to be implemented. We framed the study by drawing on the humanising pedagogy principles of humanisation, collaboration, and dialogue while reflecting on lived experiences. We linked these humanising pedagogical principles to Nowell et al.'s (2020) advantages of collaborative teams that also focus on humanisation. We acknowledge the similarities between humanising pedagogy and ubuntu. Mbigi (1997) reminded us that both these philosophies are founded on, and supported by, these human-centred principles, ideologies, values, and beliefs:

Solidarity, kindness, cooperation, respect, and compassion. Ubuntu, when embraced correctly, can therefore promote and nurture communal living, coexistence, and interdependence in educational settings. (p 31)

This article only focuses on humanising leadership principles as they align with humanising pedagogy, which is one of the guiding philosophies of our institution and our faculty. The use of a democratic leadership style is proposed because it embraces humanising principles; and the use of collaborative teams is encouraged to harvest the advantages as described above.

Democratic Leadership: A Platform for Humanising Leadership Principles to be Implemented

Contemporary higher education is one of the most exacting and complex organisations, and therefore requires leadership that is built around a range of competencies and thinking (Morrill, 2010). Given the pressures of a knowledge economy, the uncertainties that characterise contemporary higher education, and the diversity of our faculty, creating a fully inclusive faculty with a humanising approach to decision making can be a challenge. A plethora of leadership styles and theories are available. Mango (2018) explicated that this abundance of leadership theories is not only overwhelming, but also poses a challenge when trying to situate oneself within a clearly definitive leadership style.

The Nelson Mandela University vision, mission, and institutional values encourage the use of a participatory approach to leadership and decision making. Our institution's teaching and learning are underpinned by a humanising pedagogy that is premised on principles of mutual trust, collaboration, and participatory decision making. These principles create a platform to work towards social justice and transformation for the good of all. Guided by these humanising pedagogical principles that underpin the core business of the university, it makes sense to employ a leadership style that embraces similar principles of participation and collaboration. The required leadership style needs to have a strong focus on inclusivity and recognition of the human dimensions of what leadership entails. One leadership style that embraces these humanising principles is the democratic leadership style.

According to John Dewey (1916), democracy is much broader than a political form that makes laws; instead, it is a way of living as well as freedom of the intellect for effective independence. Dewey (1916) regarded participation as an important aspect of democracy and argued that active involvement and access to social dialogue are the foundations of democratic communication. Democracy is thus considered as a system in which those who will be directly affected actively participate in the decision-making process (Mbotya, 1999). In furthering this argument, Raelin (2012) contended that dialogue is an authentic exchange between people, and extends their knowledge while allowing them to reflect on different perspectives with the prospect of learning. Furthermore, he argued that dialogue builds trust and mutual understanding that lead to collaborative action (Raelin, 2012). For Paulo Freire (1970), dialogue was a creative act based on humility and commitment to others in an attempt to learn in order to name the world. It is an educative process that leads to action (Freire, 1970).

Democratic leadership is a collaborative style that can be effective with committed team members who are open to new ideas. Rustin and Armstrong (2012) postulated that this approach could also lead to the discovery of untapped potential in the professional development of colleagues. They mentioned that this leadership style balances decision-making responsibility because everyone is given a seat at the table and the discussions are relatively free flowing. Democratic leaders actively participate in discussions and value the collaborative processes. Mango (2018) explicated that democratic leadership is theoretically different from authoritarian leadership. The characteristics of democratic leadership include delegating duties and commitments amongst stakeholders, empowering team members, and enabling collaborative decision-making processes.

Thus, democratic leadership is an inclusive approach that requires team members to be committed to a common goal and to work toward the common good (Kiliçoglu, 2018). Woods (2004) argued that an aspect of the democratic leadership's conceptual framework is democratic advocacy. He posited that democratic advocacy consists of four democratic rationalities, namely, decisional (participation and influencing of decision-making), discursive (possibilities for open deliberation and dialogue), therapeutic (creation of well-being, social cohesion, and positive feelings of involvement), and ethical (aspirations to truth, and who and what is counted as legitimate contribution).

Democratic leadership also involves the delegation of responsibility amongst team members, empowering and supporting them through collaborative decision-making (Terzi & Derin, 2016). Democratic leadership further prioritises the transformation of opinion through deliberation and dialogue with the intention of reaching consensus (Dryzek, 2005). Dryzek (2005) further contended that deliberation requires fair terms of cooperation and a commitment to reciprocity by all involved.

The leadership practices in the faculty of education at Nelson Mandela University are founded on the characteristics of democratic leadership. This provided a platform to explore the implementation of humanising pedagogy principles to empower ourselves and our teams for sustainability.

Methodology

This study is located in a critical research paradigm and aims to emancipate and to give voice to a group of women leaders in the faculty of education at Nelson Mandela University. A paradigm comprises "the abstract beliefs and principles that shape how a researcher sees the world, and how he/she interprets and acts within that world" (Kivunja & Kuyini 2017, p. 26). Critical research assumes that reality is socially constructed, and that truth is authenticated through more than just reviewing the social world. This confirms the importance of reflection and action processes to establish truth and to bring about transformation (Freire, 2000). The epistemological assumptions of critical theory specify that knowledge is power if it can be implemented in practice to empower people through a process of collaborative meaning making. The authors of this article align themselves with the axiological beliefs of critical theory, which emphasise the principles of equality, fairness, social justice, inclusivity, and human rights. The term "axiology" is of Greek origin and means "value" or "worth." Li (2016) noted that axiology relates to the role of the researcher's own value at all stages of the research. This study was premised on a qualitative research approach (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Specific human challenges were investigated to enhance our understanding of how we make sense of our working world and our experiences in it (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Self-improvement requires deep reflection that involves personal introspection. Reflection helps participants to become more conscious of their thoughts, emotions, and beliefs (Mortari, 2015). In addition, self-reflection encourages the examination of current behaviour to plan for an improved future (Mortari, 2015). Reflection is necessary in "designing, implementing, learning through, and evaluating one's leadership style" (Zuber-Skerritt, 2018, p. 519). We were of the opinion that reflecting on guiding questions would enable us to learn about ourselves, others, and our knowledge of leadership. We set the reflective questions as a community and as an appropriate tool to generate valuable data. The knowledge gained through critical reflection assisted us to change and enhance our leadership processes in the faculty.

The following reflective questions guided our research:

• How would you describe your leadership style with reference to specific characteristics of your leadership style?

• Describe the relationship you have with the other members of the leadership team and how you work together.

• How does this collaboration with the other members of the leadership team help you in your leadership task?

• What is the impact of this collaboration for your department/faculty?

We reflected on these questions by utilising narrative freewriting (Elbow, 1973). Freewriting elicits thinking and the expression of thoughts through narratives that enhance learning and development. Freewriting further reduces the mental complexity of trying to "think of words and also worry at the same time whether they are the right words" (Elbow, 1998, p. 5). Spiri (2019) proposed that during a freewriting activity, the authors need to continue writing for 10 minutes without pausing to read, correct, or delete anything that they have written. Authors are urged to write even if they cannot think of something to write. They are encouraged to keep on without focusing on accuracy or linguistic correctness (Elbow, 2000; Elbow & Belanoff, 2000). Li (2007) highlighted that the intention of freewriting is to afford authors a free-flowing array of thoughts on a given theme, consequently creating understanding of that concept. Freewriting has the potential to be an engaged space for humanising pedagogy, encouraging authors to deliberate through critical questions, dialogue, and reflection. Guided freewriting can enable authors to reflect on their objectives, beliefs, and values and can serve as a complement to the personal or collective experiences of women in leadership.

This study employed collaborative self-study as the research design, thereby enabling us to reflect on our personal experiences as women in leadership. According to Stenhouse (1975), the collaborative self-study proposes a systematic and methodical approach that allows researchers to enhance their practices. A crucial characteristic of such researchers is their ability to focus on self-enhancement by engaging in systematic self-study and then participating in critical dialogue on the findings (Stenhouse, 1975). This research strategy allows researchers the freedom to investigate their own practice and to identify the underlying motivations, beliefs, and values that inform their practices. The utilisation of a self-study approach not only enabled us to reflect and improve our own practice, but also to contribute to the debate regarding women in leadership.

We drew on the research of Kitchen and Russell (2012), Tidwell et al. (2009), and Dillon (2017) who postulated that self-study as a methodology allows researchers to explore their own practices. In responding to the reflective questions, we focused on individual endeavours within our own departments as well as what we did collaboratively as a team. According to Mkhize-Mthembu (2022), self-study research utilises various methods such as arts-based and memory work to answer the research questions. We engaged with narrative freewriting in this study, enabling us to reflect on our experiences by recalling them from memory.

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown restrictions, we were confined to online platforms to compile our freewriting narratives. We held a Microsoft Teams meeting in which we were given time to respond to the reflective questions using freewriting. We subsequently shared our freewriting narratives with each other via email and met to discuss what we had written. In this transformative research paradigm, a democratic space was created for all participants' voices to be heard.

Based on the principle of democracy, the knowledge and experiences of all of us as participants were valued and recognised during the group interactions. We highlighted the main points of our narrative freewriting, and shared these with one another. We further allowed for clarifying questions to be asked. Individual lists were then compiled of key words from our narratives, and we subsequently compared our lists to identify common key words that would serve as themes for further discussion. These common key words validated the identification of the following four themes: leading through collaboration, social justice and empowerment, a compassion to serve, and self-care. We agreed to record our discussion and later transcribed it verbatim. Ethical approval for this research was not required because we were reflecting on our own practice. Méndez-López (2013) maintained that there are no formal regulations regarding the writing of a narrative account because it is the meaning that is important; it is not the making of a highly academic text. We see ourselves as being liberated and representing ourselves-we are not colonised beings, nor are we subjected to others' agendas or reduced to the position of subordinates.

The analysis of our freewriting and the subsequent discussion highlighted the following findings: the need for collaboration amongst teams to support a humanising approach to leadership, the need to create a socially just work environment where staff members are equally supported to achieve their goals, the requirement for compassion and mindfulness of the lived realities of staff members, and the importance of self-care for leaders to fulfil their leadership role effectively. These findings will be discussed below.

Discussion of Findings

In this section, the themes and subsequent findings that emerged during the data analysis are discussed and linked to the characteristics of democratic leadership, the principles of a humanising pedagogy, and the advantages of collaborative teaming. The themes identified were (1) leading through collaboration, (2) social justice and empowerment, (3) a compassion to serve, and (4) self-care to self-empower. A brief discussion of each of these themes follows.

Leading Through Collaboration

The data revealed that the authors placed a high value on collaborative leadership. The following quotes from our data supports this view: Heloise said: "I collaborate with my team in merging their personal goals with that of the department so that we can collectively achieve the departmental goals." Helena also referred to this in the following statement:

As a leader, I need to be able to give my team the freedom to openly discuss their views and to feel that it is a safe environment for them to share their concerns. I like a lively discussion and to listen to different opinions as we collaborate.

Freire (1970) reminded us that the humanising of education helps humans to understand their place and role in the world. This facilitates the way humans think, act, and engage with others and themselves. Engaging with others refers to collaboration that involves the sharing of responsibilities, as well as information and resources that support working towards a common goal (Owens & Wong, 2021). Using collaboration supports Wood's (2004) decisional democratic rationality because it encourages active participation and allows for influencing decision making. Collaboration in our respective teams assisted us to establish full and equal participation of team members in the faculty.

The process of collaboration we follow in the faculty is democratic and participatory, striving to include all voices, encouraging human agency, and human capacities to support change. Muki highlighted: "My relationship with my team members is open, honest, and inviting for new and fresh ideas." Tobeka agreed, saying: "We have a collaborative relationship; we work constructively when we have a common project/challenge with a common goal."

As leaders, we design staff learning around creating a vision for our faculty, informed by stories and ideas collected from students, lecturers, and community members. Heloise reflected on this process as follows: "I inspire, motivate, and encourage team members to work together in order for us to reach specific goals and to ensure we realise our vision." Muki responded by saying: "I do not interfere with the work that my team does as long as it reflects the values of the institution and is aligned to the vision and mission of the faculty." We found that increased collegiality amongst faculty members provided moral support and promoted confidence as well as enhanced our focus on teaching, learning, research, and engagement. In our engagement, we found that the leader and the team members are equal parts of the same goal, and that we merely have different tasks and responsibilities. Darder (2006) emphasised that Freire had believed that individuals have an ability to reconstruct themselves in collaboration with others.

We are of the opinion that a learning leadership environment reflects emancipatory conditions. A critical safe space has been created in the faculty for team members to voice their opinions and engage in transformative action. A collaborative approach to humanising pedagogy allowed us the opportunity to see the possibilities, the challenges, limitations, and barriers-not only for ourselves as leaders, but also for our team members. As leaders, we are faced with real-life problems, and we have to encourage our teams to seek solutions that will support the common good. The solutions are shared amongst us, and we are encouraged to continue the process of questioning, ultimately seeking the best solution for the collective.

Dialoguing is imperative to the process of collaboration. In our faculty, as Heloise mentioned:

I am able to learn from the other team members in how they do things in their departments. We are honest and frank with each other and this also encourages self-examination and contributes to growth and development. We call each other out if one of us does something that is out of line. We collaborate in solving problems.

Deidre emphasised the following: "Allowing your team the liberty of voicing their opinions, even disagreeing with you, is necessary-it gives them a sense of belonging and fosters good working relationships." She further highlighted: "I realised I lacked the sense of introspection; it left me extremely exhausted because I was helping others without helping myself." We realised through our engagement with our team members that humanising leadership cannot be packaged and sold as a one-size-fits-all model; we reached this realisation through continuous reflection and action.

Social Justice and Empowerment

The data suggest that we are aware of our critical role in transforming leadership practices through empowerment. The data confirms that we are aware of divisions and inequalities caused by our apartheid past and that we strive to create safe spaces for equal participation in decision making. The following extracts from the data serve as reference: Muki said:

My leadership style is democratic, caring, and persuasive. I like that people should have an opinion and contribute to matters that are discussed before a matter is decided upon. I like to delegate responsibility so that others get a chance of having the responsibility to lead in a certain area.

In similar vein, Deidre stated: "I follow the path of delegative leadership by delegating certain tasks to certain team members that utilise their strengths to achieve both individual and departmental goals."

Higher education institutions are known as spaces that foster inequalities. We consequently had to courageously address difficult or complex topics that are often ignored in the workplace such as privilege, racism in the workplace, and racially biased hiring and promoting practices. It is important for faculties to create humanising spaces that promote the values of freedom and fairness for all. In our faculty, we have employed the courageous conversation strategy (Zinn & Rodgers, 2012) to help us determine and create awareness of who we are as well as the numerous social identities we construct in the workplace. This strategy embraces Wood's (2004) discursive democratic rationality and allows us to engage in open deliberation and dialogue. We used the courageous conversation strategy to examine our behaviours, attitudes, feelings, and ideas and how these align with core values of the faculty and the institution. Deidre highlighted the importance of social justice as follows:

I would like to believe that my interaction with my team members is embedded in the principles of fairness, justice, transparency, and, above all, humanity. Thus, I engage in courageous and open conversations with staff about challenges and concerns they might have.

Heloise reiterated this in the following statement:

It is important to be aware of the realities of injustice and how it is perceived. It is further important to address these injustices and the perceptions thereof by openly and honestly engaging staff in courageous conversations regarding the issues that concern them and to collectively construct a way forward.

We live in contradiction because many of us come from a monocultural experience at home, to the faculty space that is characterised by diversity regarding nationalities, race, culture, religion, class, gender, and sexual orientation. This creates a challenge because we lack practice in effectively engaging across cultures. To engage with the differences and the challenges this poses, leaders need to employ effective listening skills and ask critical questions. It further requires leaders to pause and reflect on the complex nature of human dynamics that occur at the junctures of diversity (Owens & Wong, 2021). In this vein, Tobeka emphasised:

The heart of leadership for me is about authentic growth, vulnerability, and courageous transparency. We can nurture a rare opportunity to dare to venture into the hearts of those we lead. I know my team members and I have a genuine interest in their well-being as well as that of their loved ones. I make time to get to know the strengths and weaknesses, limitations and challenges of my team members.

Freire (1970) and Darder (2006) reminded us that that we are not complete as human beings, but that we are in a continuous process of becoming. Our becoming happens in an environment where we have to navigate, higher education policies and practices as well as our own thoughts, which have been conditioned through a culture of competition to approve of and support inequalities.

As leaders and teams, we need to create environments that encourage equal opportunities for all, regardless of race, gender, religion, physical, or learning ability. Empowering leadership creates a relationship between formal leadership and the informal processes that can lead to novel problem solving and transformation for the good of all (McKibbin & Fernando, 2020). We realised that enabling leadership amongst racially and culturally diverse individuals can facilitate the creation of novel forms of knowledge, skills, abilities, and solutions needed for our faculty to move forward in the most adaptive way possible (McKibbin & Fernando, 2020). Engaging in these courageous conversations also enabled us to reflect on inequalities in the community we serve, and to strive towards social justice in our engagement projects. Usman et al. (2021) postulated that focused engagement allows leaders to direct processes along the required path by emphasising connection through mutually beneficial collaboration. In her reflection, Heloise also referred to the community that the university serves, and how important it is to link what we do in the faculty with societal needs in order to bring about true social transformation. This highlights the fourth advantage of collaborative teams, namely, that of working towards the common good.

A Compassion to Serve

Globally, we have seen an increase in the focus of leaders to serve with compassion. Reflecting on our leadership styles in this research was intentional in order to identify whether our leadership styles were humanising in nature or not. The results of the study show that our leadership styles are true examples of caring and nurturing leadership, and being responsive to the needs of our team members as the following statements show:

Tobeka: I am sensitive to the needs of those I work with and those I lead.

Helena: My staff members' wellness is very important to me, and I encourage them to take care of themselves emotionally.

Offering support by being vulnerable as a leader has appeared as a strategy by means of which to foster the confidence of staff members to be vulnerable as well, and to open up about their struggles. There is agreement in literature that support in the workplace is one of the important ways of enacting a compassionate response in times of crisis (Poorkavoos, 2016; Tehan, 2007). Compassion at work has been viewed as promoting the social and psychological connectedness of workers (Poorkavoos, 2016). Research also indicates that there is a close link between social connectedness and personal well-being (Tehan, 2007).

In a faculty that is guided by a humanising pedagogy, it is not surprising that the characteristics of compassion were more evident than the other three themes in the results of this study. Even though it is natural for women to be nurturing and compassionate, one commends the conscious efforts to create an environment that is supportive to the growth of the individuals and teams, and where people feel safe and secure in having their opinions listened to and considered (Walters et al., 2021). Our leadership styles show that we are inclusive in that we acknowledge the input of the members of our teams because they are people and, as such, have voices. Practising compassion emphasises Wood's (2004) therapeutic democratic rationality given that it encourages staff involvement and contributes to staff wellness. The following statements from our reflective freewriting serve as reference:

Heloise: I seek the opinions of staff member before making decisions.

Helena: I like to discuss issues with my team.

Muki: I like that people should have an opinion and contribute to decision making.

Deidre: I firmly believe in involving team members in decision-making.

Tobeka: I try to listen to what everyone says.

According to Hougaard and Carter (2018), team members want to be engaged, and appreciate being involved in decision-making-contrary to what many leaders and managers believe. They further postulated that involving team members in decision making and asking them for their opinion contributed to staff well-being and subsequently correlated with contentment, a factor associated with the retention of staff.

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the link between leadership and compassion had been questioned (Walters et al., 2014), however, the pandemic revealed the necessity for leadership styles that were compassionate in nature because they enhance staff morale and contribute to a positive work environment (Ngambi, 2011). In the years 2020 and 2021, more than ever, leaders needed to lead from the heart as the country and the world were plagued by grief and the loss of workers, co-workers, and loved ones. The physical, emotional, and mental struggles brought about by the pandemic were real. The lived realities of leading staff working under these stressful conditions and troubled by depression, sense of loss, and sense of isolation, amongst others, led us to think deeply about our leadership styles. The pandemic taught us the need for human-centred approaches to leadership.

Self-Care to Self-Empower

The importance of self-care was highlighted by all five authors, all believing that taking care of oneself will help one to take care of others. Self-care helps one function at one's best and it thus plays an important role in determining how one will lead. The following statements from the data serve as evidence of the value placed on self-care:

Tobeka: As a compassionate leader I am aware that in order to support and nurture my team I also need to take care of myself.

Helena: My staff's wellness is very important to me, and I encourage them to take care of themselves emotionally. I try to practise what I preach by deliberately creating spaces to talk about self-care.

Self-care is a necessary lifestyle practice for good health. Leaders who practise self-care demonstrate to their teams the importance of wellness as they make an effort to be present for their teams in a personal and professional capacity. Self-care enhances resilience because it contributes to increased energy levels and serves as motivation to feel good about yourself (Riegel et al., 2021). Nowell et al. (2020) referred to the ethics of care as an advantage of collaborative teams, highlighting that it refers to assenting norms related to a commitment by the individual to take care and provide a service. The following responses were made by the authors, and show evidence of the ethics of care. Heloise stated: "I lead by example. I would not expect staff do something that I myself will not do." Deidre and Helena also make mention of the importance of being self-aware and learning from mistakes. According to Anãlayo and Dhammadinnã (2021, p. 1353), "multidimensional self-care is important to incorporate as an essential leadership practice to facilitate a culture of resilience and well-being in the workplace."

Compassion is one of the leadership qualities valued by this team; however, one cannot have compassion for others if one does not have compassion for oneself. Walters et al. (2021) postulated that it is difficult for women to practise self-care because they feel they have to prove their value to others and work twice as hard to earn respect and acknowledgement. Women are programmed to sacrifice themselves and always support others. They need to reach the stage where they realise that self-care is vital and they should not feel guilty when they need to take time out (Walters et al., 2021). As a strong leader, you need to be able to lead by example and to take care of yourself.

Practising self-care also serves as an opportunity to exemplify the practice to your staff. A happy staff is a productive staff. Thus, we strive as leaders to instil the value of self-care in our teams. Attitudes have the ability to influence others. If a leader ignores the need for self-care, it will negatively impact their teams and subsequently influence their well-being and productivity (Riegel et al., 2021). Developing a culture of self-care contributes to the prevention of burnout amongst team members and will subsequently encourage higher levels of productivity, employee engagement, and staff morale throughout an organisation (Ngambi, 2011). We need to realise that self-care can sometimes mean that we need to delegate responsibilities to other team members, and that we cannot be the best in everything we do (Walters et al., 2021).

Bryan and Blackman (2019, p. 21) wrote the following:

The pressure to meet the multiple demands of higher education, alongside personal goals and diverse value-systems, can make it difficult to prioritize self-care. As such, higher education lifestyles, which are propelled by distinctive career or academic goals, may include self-sacrificing and self-compromising practices, which can lead to chronic stress.

It is thus imperative that effective self-care strategies in and outside the workplace be established. Riegel et al. (2021) listed setting realistic goals, developing effective work boundaries, as well as maintaining a healthy balanced lifestyle as effective self-care strategies. We found that when it came to modelling wellness to our teams, openness and action were paramount.

A Humanising Leadership Model

This study revealed a link between democratic leadership and applying humanising pedagogy principles. The purpose of the study was to reflect on our own leadership practices and how collaborating with each other encouraged empowerment of the self and others. Darder (2021) explicated that transformative knowledge can only be built through personal involvement in collective and collaborative struggle with others. This requires an openness to the world around us, and through sustained dialogues about experiences of everyday life and lived histories.

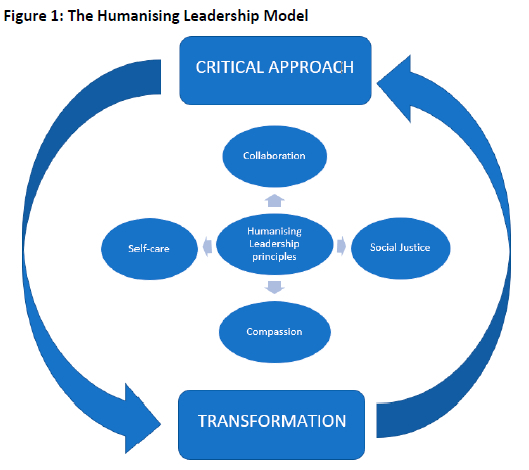

Our reflections and subsequent findings highlighted the need for us to co-construct a humanising leadership model in which we indicate the four themes that were revealed in the study as important elements of applying humanising principles to leadership. The goal of our co-constructed leadership framework is to develop and support accountable, committed, responsive, and compassionate leaders with a strong commitment to learning and the ability to continually develop oneself and others. The advantages that we reap from this leadership approach are all strongly entrenched in the foundations of human dignity, respect, equality, and growth capacity-and they underline the importance of co-construction and social good. This proposed leadership model resides within a critical paradigm and aims to bring about transformation in leadership and, in turn, contribute to social transformation. The construction of the model is grounded in our readings and practices of a humanising pedagogy as one of the guiding philosophies at our institution. The discussion of our freewriting led us to the identification of themes that were aligned to the humanising pedagogical principles of collaboration, compassion, social justice, and self-care (Darder, 2021). Our discussions and reflection on our lived experiences helped us realise the need to share the value of applying these principles by constructing the humanising leadership model in Figure 1.

The humanising leadership model emphasises the link between democratic leadership and humanisation. Humanisation as a strand of critical pedagogy seeks to bring about transformation, while the model illustrates that in order for this to happen, certain principles need to be applied. The principles identified in this paper are collaboration, compassion, social justice, and self-care. We acknowledge that these are not the only principles that could impact humanising leadership, and we acknowledge that all four principles do not have to be present at the same time or applied at the same intensity levels.

Our study also revealed a lack of research on the link between democratic leadership, humanising principles, and self-care. This serves as impetus for an investigation into self-care and the possibility of developing a pedagogy of self-care. A pedagogy of self-care could provide more guidelines to support leaders to take care of themselves and their teams.

Conclusion

This article shared how collaboration and humanising leadership principles can contribute to the growth of both the leadership team and the faculty. Our co-constructed model is premised on a democratic leadership style. We used narrative freewriting to make sense of how we lead as individuals and as a team. The generated data were then categorised into themes from which key leadership principles that guide the leadership process were extrapolated. Collaboration, social justice, compassion, and self-care are the themes that emerged.

The article provided a synopsis of the leadership model co-constructed and embraced by five women leaders in the faculty of education at Nelson Mandela University. This model is framed by a critical humanising pedagogy and subsequently foregrounds the value of human dignity and a fully inclusive approach. A humanising pedagogy and collaborative leadership model thus emerged as critical in this context.

The shift from women leaders holding power to empowering each other critically, as well as the rest of faculty, through a humanising ethics of care comes through as a strong element in the study. This allowed for the co-construction of the humanising leadership model that provides guiding principles to enhance leadership practices. The model emphasises the link between democratic leadership and humanisation. It also exposes the need for further research regarding a pedagogy of self-care. This article highlighted the need for a review of leadership practices, and raises questions regarding how leadership can contribute towards equality, sustainability of the organisation, and the empowerment of leaders.

References

Anãlayo, B., & Dhammadinnã, B. (2021). From compassion to self-compassion: A text-historical perspective. Mindfulness, 12(6), 1350-1360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01575-4 [ Links ]

Apple, M. (2004). Ideology and curriculum. Routledge.

Bryan, V., & Blackman, G. (2019). The ethics of self-care in higher education. Emerging Perspectives, 3, 14-34. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342666861 [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approach (5th ed). SAGE.

Darder, A. (2006). Teaching as an act of love: Reflections on Paulo Freire and his contributions to our lives and our work. In A. Darder, M. Baltodano, & R. D. Torres (Eds.), The critical pedagogy reader (2nd ed., pp. 567-578). Routledge.

Darder, A. (2021). The profound solidarity of Paulo Freire. Postcolonial Directions in Education, 10(2), 1903-214. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/86513 [ Links ]

Del Carmen Salazar, M. (2013). A humanizing pedagogy: Reinventing the principles and practice of education as a journey toward liberation. Review of Research in Education, 37(1), 121-148. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X12464032 [ Links ]

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. The Free Press.

Dillon, D. (2017). Straddling teacher candidates' two worlds to link practice and theory: Self-study of successful and unsuccessful efforts. Studying Teacher Education, 13(2), 145-164. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2017.1342352 [ Links ]

Dryzek, J. S. (2005). Deliberative democracy in divided societies: Alternatives to agonism and analgesia. Political Theory, 33(2), 218-242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591704268372 [ Links ]

Elbow, P. (1973). Writing without teachers. Oxford University Press.

Elbow, P. (1998). Writing with power (2nd ed). Oxford University Press.

Elbow, P. (2000). Everyone can write. Oxford University Press.

Elbow, P., & Belanoff, P. (2000). A community of writers: A workshop course in writing. McGraw-Hill.

Foley, J. A., Morris, D., Gounari, P., & Agostinone-Wilson, F. (2015). Critical education, critical pedagogies, Marxist education in the United States. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 13(3), 110-144. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290251981_Critical_education_critical_pedagogies_marxist_education_in_the_United_States [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1984). The Foucault reader. Pantheon.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th anniversary ed.). Continuum.

Geduld, D., & Sathorar, H. (2016). Humanising pedagogy: An alternative approach to curriculum design that enhances rigour in a B.Ed. programme. Perspectives in Education, 34(1), 40-52. https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v34iL4 [ Links ]

Giroux, H. (2007). Democracy, education and the politics of critical pedagogy. In P. McLaren & J. L. Kincheloe (Eds.), Critical pedagogy: Where are we now? (pp. 1-5). Peter Lang.

Hougaard, R., & Carter, J. (2018). The mind of the leader: How to lead yourself, your people, and your organisation for extraordinary results. Harvard Business Review Press.

Khilji, S. (2021). An approach for humanizing leadership education: Building learning community and stakeholder engagement. Journal of Management Education, 32(4), 1-33. https://doi.org/10.1177/10525629211041355. http://journals.sagepub.com/home/jmd [ Links ]

Kiliçoglu, D. (2018). Understanding democratic and distributed leadership: How democratic leadership of school principals related to distributed leadership in schools? Educational Policy Analysis and Strategic Research, 13(3), 6-23. https://doi.org/10.29329/epasr.2018.150.1 [ Links ]

Kitchen, J., & Russell, T. (Eds.). (2012). Canadian perspectives on the self-study of teacher education practices. Canadian Association of Teacher Education.

Kivunja, C., & Kuyini, A. B. (2017). Understanding and applying research paradigms in educational contexts. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(5), 26-41. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v6n5p26 [ Links ]

Lawton-Misra, N. (2019). Crisis leadership at South African universities: An exploration of the effectiveness of the strategies and responses of university leadership teams to the #FeesMustFall (#FMF) protests at South African universities in 2015 and 2016 [Doctoral dissertation, University of the Western Cape]. https://etd.uwc.ac.za/handle/11394/7096?show=full [ Links ]

Li, L. Y. (2007). Exploring the use of focused freewriting in developing academic writing. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 4(1), 46-60. https://doi.org/10.53761/L4.L5 [ Links ]

Li, Y. (2016). Expatriate manager's adaption and knowledge acquisition: Personal development in ultinational companies in China. Springer.

Mango, E. (2018). Rethinking leadership theories. Open Journal of Leadership, 07(1), 57-88. https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinforcitation.aspx?paperid=83142https://doi.org/10.4236/ojl.2018.71005 [ Links ]

Mbigi, L. (1997). Images of ubuntu in global competitiveness. Flying Springbok, 4, 31-35. [ Links ]

Mbotya, S. F. (1999). Democracy in education: A necessity for South Africa. St. Cloud State University.

McKernan, J. A. (2013). The origins of critical theory in education: Fabian socialism as social reconstructionism in nineteenth century Britain. British Journal of Educational Studies, 61(4), 417433. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2013.824947 [ Links ]

McKibbin, W. J., & Fernando, R. (2020). The global macroeconomic impacts of Covid-19: Seven scenarios (CAMA Working Paper No. 19/2020). https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3547729

Méndez-López, M. (2013). Autoethnography as a research method: Advantages, limitations and criticisms. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 15(2), 279-287. http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2013.2.a09 [ Links ]

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed). John Wiley & Sons.

Mkhize-Mthembu, N. S. (2022). Finding myself by involving children in self-study research methodology: A gentle reminder to live freely. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 2(1), Article 1043. http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sciarttext&pid=S2223-76822022000100010 [ Links ]

Moodly, A. L., & Toni, N. M. (2017). Re-imagining higher education leadership: In conversation with South African female deputy vice-chancellors. Perspectives in Education, 35(2), 155-167. https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v35i2.12 [ Links ]

Morrill, R. (2010). Strategic leadership integrating strategy and leadership in colleges and universities. Rowman & Littlefield.

Mortari, L. (2015). Reflectivity in research practice: An overview of different perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(5), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406915618045 [ Links ]

Ngambi, H. C. (2011). The relationship between leadership and employee morale in higher education. African Journal of Business Management, 5(3), 762-776. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM10.854 [ Links ]

Nowell, L., Dhingra, S., Andrews, K., Gospodinov, J., Liu, C., & Hayden, K. A. (2020). Grand challenges as educational innovations in higher education: A scoping review of the literature. Education Research International. Article 6653575. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6653575

Owens, T., & Wong, A. (2021). Collaboration, empathy and change: Perspectives on leadership in libraries and archives in 2020. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/3gnds

Poorkavoos, M. (2016). Compassionate leadership: What it is and why organisations need more of it? Research Paper, Roffeypark Institute. http://affinityhealthhub.co.uk/d/attachments/2-compassionate-leadership-booklet-1558606680.pdf

Raelin, J. A. (2012). Dialogue and deliberation as expressions of democratic leadership in participatory organizational change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 25(1), 7-23. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811211199574 [ Links ]

Riegel, B., Dunbar, S. B., Fitzsimons, D., Freedland, K. E., Lee, C. S., Middleton, S., Stromberg, A., Vellone, E., Webber, D. E., & Jaarsma, T. (2021). (2021). Self-care research: Where are we now? Where are we going? International Journal of Nursing Studies, 116, 103402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103402 [ Links ]

Rustin, M., & Armstrong, D. (2012). What happened to democratic leadership? Soundings, 50(50), 59-71. https://doi.org/10.3898/136266212800379482 [ Links ]

Sathorar, H. (2018). Exploring lecturer preparedness on applying a critical approach to curriculum implementation: A case study [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Nelson Mandela University, South Africa. [ Links ]

Seale, O., Fish, P., & Schreiber, B. (2021). Enabling and empowering women in leadership in South African universities: Assessing needs and designing a response. Management in Education, 35(3), 136-145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020620981951 [ Links ]

Shingler-Nace, A. (2020). Covid-19: When leadership calls. Nurse Leader, 18(3), 202-203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2020.03.017 [ Links ]

Spiri, J. (2019, May 18-19). Freewriting for writing development [Paper presentation]. PanSIG Conference, Konan University, Nishinomiya, Japan.

Stenhouse, L. (1975). An introduction to curriculum research and development. Heinemann.

Teague, L. J. (2015). Higher education plays critical role in society: More women leaders can make a difference. Forum on Public Policy Online, 2015(2). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1091521 [ Links ]

Tehan, M. (2007). The compassionate workplace: Leading with the heart. Illness, Crisis and Loss, 15(3), 205-218. https://doi.org/10.1177/105413730701500303 [ Links ]

Terzi, A. R., & Derin, R. (2016). Relation between democratic leadership and organisational cynicism. Journal of Education and Learning, 5(3), 193-204. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v5n3p193 [ Links ]

Tidwell, D., Heston, M., & Fitzgerald, L. (Eds.). (2009). Methods for self-study of practice. Springer.

Usman, M., Liu, Y., Li, H., Zhang, J., Ghani, U., & Gul, H. (2021). Enabling the engine of workplace thriving through servant leadership: The moderating role of core self-evaluations. Journal of Management and Organization, 27(3), 582-600. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2020.11 [ Links ]

Walters, C., Ronnie, L., Jansen, J., & Kriger, S. (2021). "Academic guilt": The impact of the pandemic-enforced lockdown on women's academic work. Women's Studies International Forum, 88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2021.102522 [ Links ]

Woods, P. A. (2004). Democratic leadership: Drawing distinctions with distributed leadership. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 7(1), 3-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360312032000154522 [ Links ]

Zinn, D., & Rodgers, C. (2012). A humanising pedagogy: Getting beneath the rhetoric. Perspectives in Education, 30(4), 76-87. [ Links ]

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2018). An educational framework for participatory action learning and action research (PALAR). Educational Action Research, 26(4), 513-532. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2018.1464939 [ Links ]