Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Educational Research for Social Change

versão On-line ISSN 2221-4070

Educ. res. soc. change vol.12 no.2 Port Elizabeth Out. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2023/v12i2a4

ARTICLE

Reflecting on Teaching in the Higher Education Context During the Covid-19 Era: A Collaborative Self-Study Project

Makie KortjassI; Ntokozo Mkhize-MthembuII

ISchool of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal. Kortjassm@ukzn.ac.za; Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5605-5049

IISchool of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal. MkhizeN39@ukzn.ac.za; Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7777-8780

ABSTRACT

The advent of the Covid-19 pandemic created unimaginable upheaval, uncertainty, and even hostility in the education system, worldwide. Teacher educators in higher education settings were compelled to interact with their students using online platforms to ensure the continuation of teaching and learning. However, the effectiveness of that approach has been questioned. This article presents the narratives of two South African teacher educators who explored pedagogical approaches using such digital platforms. We created collages, concept maps, and a pantoum poem to reflect on our teacher educator practices during the initial and ensuing levels of the Covid-19 lockdown period to provide guidelines for such approaches in the aftermath of the pandemic. We gained various insights into future teaching practices using arts-based media and platforms such as WhatsApp, Moodle, Zoom, and Microsoft Teams. The sociocultural theoretical perspective underpinned this self-study project. This theoretical approach highlights the importance of working together in educational settings to create knowledge and make sense of teaching and learning experiences. We discovered that the transition to digital platforms presented both advantages and disadvantages for our teaching. In the latter instance, we found that teaching and learning using digital platforms were rendered inefficient for students from rural settings who were computer illiterate and who had limited access to technology and the internet. However, by conducting workshops, engaging in collaborative initiatives, and appropriating feedback from various role players, we gained understanding of ways to support our students and address their diverse needs. In light of these findings, we recommend intensified teacher educator collaboration and sharing to reimagine and reshape teaching and learning in the higher education teacher training context in the post-Covid-19 era.

Keywords: arts-based research, Covid-19 pandemic, online platforms, self-study, teacher education

Introduction

We, Makie and Ntokozo, are two South African teacher educators who engage in self-study projects to improve teaching practices. Most of the students we teach are from disadvantaged backgrounds. Ntokozo is involved in the teacher development studies discipline, where her work entails teaching and supervising postgraduate students, whereas Makie teaches in the early childhood education discipline. Her work involves lecturing in the undergraduate programme and supervising postgraduate students. We have both recently completed our respective doctorates in the self-study field (Kortjass, 2020; Mkhize-Mthembu, 2020). And we subsequently aimed to enhance our learning by working collaboratively during the Covid-19 pandemic to understand how new methods and requirements might influence how we engage with our students to optimise their learning.

This article recounts our educational experiences and emerging insights during the Covid-19 pandemic. We illuminate how these experiences shaped our understanding of what teacher educator teaching and learning might constitute in the post-Covid-19 era. Our study was guided by the following research question: "What can we learn collaboratively about teaching in higher education during the Covid-19 pandemic era?" First, we outline key concepts of teacher education and online teaching in a higher education setting during the Covid-19 pandemic. We then present a discussion of the sociocultural perspective as the theoretical framework that underpinned our investigation-with particular reference to teacher educator collaborative initiatives. Second, we identify ourselves as research participants who engaged in narrative inquiry. Third, we discuss how collage making, poetry writing, and concept mapping assisted us in identifying key concepts and phrases, based on the research question. To conclude, we share some of the dilemmas we experienced and the discoveries we made as we worked collaboratively during the pandemic to assist our students.

Teacher Education

Korthagen (2017) stated that teacher learning occurs unconsciously, and encompasses the cognitive, emotional, and motivational dimensions of learning. She argued that both novice and veteran teachers are habitually unconscious of their behaviour and sources. For this reason, our study reflected consciously on our teaching practices to illuminate and contextualise our behaviours and cognitive thoughts. Darling-Hammond et al. (2017) emphasised that teacher education should embrace active learning-that teacher educators should unswervingly engage in exploring teaching approaches because this will offer them opportunities to engage in the same learning style they are designing for their students. Therefore, like our students, we had to learn virtually using digital platforms such as Moodle, Zoom, and Microsoft Teams.

Online Teaching in Higher Education During the Covid-19 Pandemic

Prior to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, most higher education institutions used online teaching only to complement face-to-face contact sessions. However, with the dawning of Covid-19 and during the lockdown phases, the teacher education system was infused with doubt, fear, and even hostility. The need to cope during the pandemic changed how we could think and interact with our students for optimal teaching and learning. We now have to envision the aftermath of Covid-19 by reflecting on both successful and unsuccessful pedagogical approaches and considering innovative learning styles. In essence, we need to review our curriculum and practices to suit the digital world. We have thus resorted to online learning to interact virtually with our students who have had to learn to access learning material in recorded slides and videos. These were also uploaded on Moodle for students who could not attend our Zoom sessions. Engaging in online teaching has forced us to find innovative ways to deliver teaching asynchronously.

Our experiences during the pandemic compelled us to see the education world differently. A critical understanding that emerged was that, in this digital-driven age, students would need to engage in more independent learning to build their knowledge and insights without being guided synchronously. Peters et al. (2020) stated that pandemics have historically forced humans to separate from the past and envision their future world in a new light. What does this mean in terms of higher education? In a nutshell, we have to revisit our pedagogic approaches and allow our students every opportunity to learn independently. On the face of it, this seems paradoxical given that the sociocultural approach we endorse argues strongly for collaborative learning. The challenge is thus to strike a balance between independent and collaborative teaching and learning in what is now commonly referred to as the new normal-which is online learning for students. Therefore, while technology offers tremendous opportunities beyond physical borders and is not limited to geographical or physical settings, various negative implications and disadvantages are associated with the demands of such learning. Not every student is privileged to engage in online learning in a developing world because many students come from poor and disadvantaged backgrounds. Peters et al. (2020) stressed this point, elucidating that their experiment in non-voluntary transposition into virtual classrooms highlighted various dimensions of unequal access such as regions with inadequate or non-existent Wi-Fi, students with low quality equipment (or none), and different levels of comfort and experience with applications like Moodle or Zoom.

Digital technology can simplify teaching and learning and influence how students and teachers process and engage with content to develop critical knowledge and thinking. However, it is hard to tell what the future holds-and how we can continue to conduct teaching and learn to create educational contexts that are equal for (and inclusive of) all because it is an undeniable requirement that all socioeconomic backgrounds and experiences need to be accommodated in educational contexts. Peters et al. (2020, p. 11) underlined the point that a pandemic such as Covid-19 "might raise this awareness for some but, for most, the uncertainty strengthens the quest for definitive answers." The uncertainty associated with the pandemic and its aftermath means that we must be proactive and should focus on methodological issues and the lessons in order to build on new knowledge and understanding of teaching in the post-Covid period.

As teacher educators, we were challenged to reimagine and reinvent teaching that was accessible to students from all social backgrounds. Neuwirth et al. (2020) stated that Covid-19 obligated institutions to adapt to unprecedented challenges and hastily convert from traditional face-to-face education to distance learning formats through virtual classrooms. Most colleges and universities worldwide had previously assimilated online teaching methods into their module/course outlines. However, the pandemic required an almost overnight transformation of curricula into virtual learning, and educators at all levels were required to build virtual classrooms. Although some universities may already have had robust online structures, many developing countries found the mass demand for virtual classrooms challenging. Most students from rural settings are not computer literate and do not have access to data-driven technology and the internet.

Peters et al. (2020) highlighted that thoughtful teaching is based on reflective dialogue and collaborative discussions in the milieu of real-time teaching situations and space. However, when we migrate to virtual learning, we need to revisit the policies that applied in the past. For example, the lack of infrastructure and teaching and learning resources need to be addressed urgently if online learning is to be effective and inclusive. Furthermore, the pandemic saw re-emergence of old questions regarding education quality and equality. It is pivotal that the social injustices in the education system that persist in certain universities are addressed. Universities that still lag in that regard can learn from those who have attempted to close this gap by exploring avenues to allow democratic learning employing digital platforms. For such processes to succeed, collaborative learning and building partnerships amongst knowledgeable and experienced role-players at universities are paramount.

There is crucial need for a coordinated, collaborative, and collective global response to the best-practice principles for online instruction. Crawford et al. (2020) explained that technology solutions do support online teaching. Such facilities include narrated PowerPoint presentations and freeware such as Skype, Google Classroom, Moodle, and Facebook. For example, by accessing Moodle, students can engage with other students from around the globe, and students and lecturers can post information on these forums. Students can use these online platforms asynchronously to have open discussions that cultivate collaborative study engagements.

A Sociocultural Theoretical Perspective

This self-study project was underpinned by the sociocultural theoretical perspective, highlighting the importance of working together in educational settings to make sense of our individual learning experiences. The sociocultural perspective advocates self-study research because it encourages collaborative learning (Samaras, 2011). Therefore, to address the dichotomy between face-to-face classroom and remote digital-based learning to some extent, we related our teaching and learning practices to the real-life experiences of our students. According to Samaras and Freese (2006), self-study research is created from knowledge based on everyday experiences and practical theories. Teacher educators develop their teaching philosophy, based on social development. We thus understand that learning is not a solo path but one that requires collaborative effort. By working collaboratively, we were able to identify new ways of teaching and learning as demanded by conditions during the pandemic. And we were able to establish an online learning community that strengthened and enhanced our efforts and insights.

Enlightened by sociocultural theory, we understand that learning is developed through our interactions with the people around us. Gerhard and Smith (2008) maintained that the sociocultural perspective believes that learning is not an individual activity but a social experience. Similarly, Samaras et al. (2014) emphasised that learning is dynamic and social and that interchange shapes individuals' psychological practices, including learning. McMurtry (2015) highlighted that social interaction is a tool that supports teachers and helps them to alter and streamline obscure understandings. Furthermore, the sociocultural perspective illuminates how learning transpires among people of diverse cultural and social backgrounds. We hoped to simplify and engender thought-provoking interactions as teacher educators by embracing the sociocultural perspective. Easton (2012, p. 50) affirmed that "learning means that we work with people [by] encouraging discoveries and learning from mistakes, [thus] helping everyone to find what works." When hitherto unexplored challenges confronted us during the pandemic, the obvious starting point was to work together by sharing ideas and exploring successful strategies using digital platforms to enhance our practice. In this process, we were compelled to question methodologies and reflect on our teaching practice-particularly, what worked and did not work for our students. We were also mindful that it would be a learning journey. We would have to make constructive discoveries and learn from our mistakes, consciously. But we knew that, through collaborative effort, we could establish a robust support system.

Diversity in education is a reality, and teacher educators must be conscious of each student's social and cultural background in order to achieve positive academic outcomes. Banks et al. (2001) advised that teachers must be informed about their students' collaborative and enlightening teaching and learning features when creating learning opportunities for them all. Similarly, John-Steiner and Mahn (1996) argued that learning and growth occur cooperatively and in culturally constructed surroundings. Moreover, the latter authors affirmed that "human functioning is tied to cultural, institutional, and historical settings since these settings shape and provide the cultural tools that individuals master to form this [educational] functioning" (John-Steiner & Mahn, 1996, p. 193). Northfield and Sherman (2004) affirmed that our actions, and how we perceive and treat one another, are founded on the values and beliefs we develop as we grow in our relationships with others. This means that we can find ourselves by building positive relationships (McMurtry, 2015) in various contexts. Working collaboratively to improve our teaching practice as teacher educators thus meant that we had to familiarise ourselves with our students' diverse cultures, social backgrounds, beliefs, and daily customs so that the digital channels of communication would be effective.

When familiar with the sociocultural theoretical perspective, teachers understand why learners behave the way they do. According to Gerhard and Smith (2008), the sociocultural perspective is a lens that can be used to scrutinise what learners learn, and who they become. Gerhard and Smith (2008) implied that this is a two-way process of scrutiny that creates a learning community in which all individuals can actively participate and thus contribute to learning. Additionally, Murphy and Ivinson (2003) stated that the knowledge acquired by participating in various such learning communities offers learners diverse possibilities for retrieving knowledge that is valued and instituted by teaching institutions. Against this backdrop, we were mindful of the diversity among our students and thus devised learning activities that accommodated their various needs and realities.

Narrative Inquiry

As self-study researchers, we continually strive to develop and improve our teaching practices. Narrative inquiry is a space where we can reflect on and share our experiences in order to address challenges and enhance our effectiveness. Hamilton et al. (2008, p. 17) described narrative inquiry as a study process "that looks at a story of self." Ford (2020, p. 237) agreed, stating that "narrative inquiry is a type of qualitative research focused on human stories." We were able to share and learn from others through interactions and conversations about our evolving teaching practices by employing this methodology in the current investigation. Narrative inquirers recognise that experience and context are not constant-but changing and shifting phenomena. Thus, temporality, sociality, and place are essential thinking tools within narrative inquiry (Clandinin, 2013). Clandinin (2013) also considered narrative inquiry to be a source of critical knowledge and understanding that people acquire over time in particular social environments.

Hamilton et al. (2008) concluded that narrative inquirers sync with the self and others' feelings, needs, and moral natures. Clandinin (2013) asserted that inquiries attend temporal ways towards the past, present, and future of the people, places, things, and events under study. The stories of people thus become a gateway through which their experiences of the world are interpreted and made personally meaningful because their stories shape their lives (Clandinin et al., 2007). We therefore recount our relevant teaching experiences as they occurred along our journey to explore the use of digital platforms during the Covid-19 era.

Sociality involves personal and social conditions. Clandinin (2013) noted that narrative inquirers must attend to these conditions simultaneously. Narrative inquiry thus helped us to understand our struggles, emotions, and experiences as we attempted to drive student learning in novel and challenging circumstances. We acknowledged that feelings were vital in the process of navigating new spaces/conditions of teaching and learning, and that our students' cultural and social settings had to be considered at all times (Clandinin & Connelly, 1998). As a methodological approach, narrative inquiry enabled us to examine and explore our experiences and selves through storytelling. We enhanced our inquiry using collages, poetry, and a concept map in this process.

Data Generation and Interpretation

Arts-Based Self-Study Methods

We examined our personal experiences by employing an arts-based self-study methodology. Tidwell and Jónsdóttir (2020) elucidated that using the arts-based method in self-study projects generates understandings that embody the social, cultural, and meaning-making contexts from which experience and engagement are developed. Using this method enabled us to break out of conventional ways of engaging in qualitative research. The arts-based media we employed to reflect on our experiences as we examined our practice were collages, a concept map, and a poem.

Collages

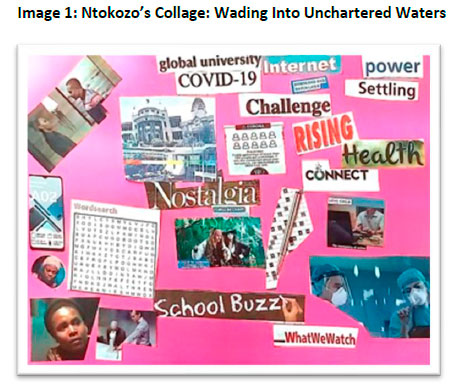

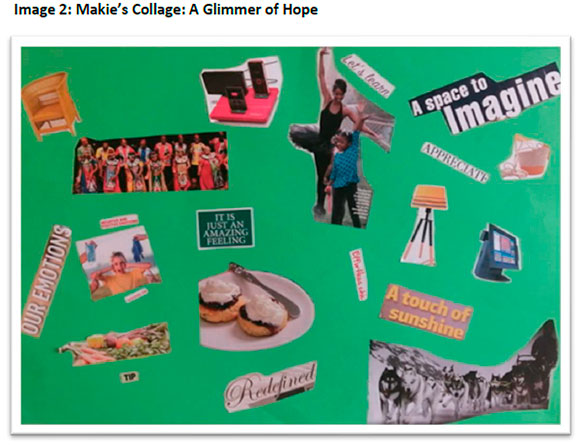

According to van Schalkwyk (2010, p. 678), the collage is an illustration that involves "the use of photos, pictures and cuttings [also text] from magazines and other media" to portray a phenomenon. When creating a collage, the researcher or participant selects and pastes magazine cuttings or pieces of fabric on paper, creatively, to influence or captivate the reader/viewer meaningfully and to reflect insight and understanding (Pillay et al., 2019). Collage research continues to gain momentum in qualitative research (Lahman et al., 2020) because it can expose and explain personal-professional connectedness in our daily practice (Pillay et al., 2019). The ability of a collage to express meaning affords researchers various ways of understanding and communicating their lived experiences. In this research project, we used two collages to reflect on our practice during Covid-19. First, we created them reflectively to focus on our questions, dilemmas, feelings, and emotions; we thus selected images that metaphorically reflected aspects of our thinking. Then, operating intuitively, we created collages that produced a holistic visual composition using selected fragments. Such a collage-creating process breaks away from the linearity of written thoughts as the subject works first from feelings about something and then shifts to the ideas they evoke-instead of the reverse (Butler-Kisber & Poldma, 2010).

Each image and text in the collages narrates the story-or a significant part of the story-about our personal and professional experiences and developmental needs during the Covid-19 period (Masinga et al., 2016). As researchers, we each created a collage and presented it individually to critical friends while articulating our experiences and understandings. All the meetings and interactions were conducted via Zoom. We recorded our discussions and transcribed them later. Considering the issue of trustworthiness, we presented our collages to critical friends for critique and extended input. Samaras (2011) described a critical friend as supporting a self-study researcher to gain new views and understandings and assist in reframing interpretations. Our purposively selected critical friends were willing to participate and contribute (Childs et al., 2020). Makie presented her collage to Simo (pseudonym), and Ntokozo presented hers to Nomali (pseudonym). We allowed ourselves a week to meet with our respective critical friend. With their permission, we recorded and transcribed our discussions. The collages are presented in Image 1 and Image 2 below.

Ntokozo's Narrative About the Images and Texts in the Collage

Face masks: The face masks worn by two men represent my feelings of doubt and uncertainty during the Covid-19 period, which were quite alien to my usual sense of confidence and purpose. I felt anxious and fearful as if I had been imprisoned, and this sense of being imprisoned compelled me to reflect repeatedly on my teaching practice. The facemasks represent how I was shielded from a clear understanding of my way forward as a teacher educator. As a result, I constantly felt remote from others and struggled to read their emotions as we were compelled to hide behind facemasks.

Word search": While it was challenging for me to engender positive energy during this pandemic, I had the opportunity to reflect on teaching practices that would hearten teacher educators and shape and strengthen human relationships, particularly those between me as a teacher educator and my students.

"Connect": While creating this collage, I was experiencing a surge of emotions that compelled me to think afresh of my position in teacher education. I aspired to explore new ways of learning and to adopt a positive mindset. I also realised that I would be nurtured by positive relationships with my colleagues, who also experienced what I was going through.

"Challenge": I also was responsible for developing learning outcomes and devising strategies to drive student learning and sustain teaching opportunities where everyone would feel accepted and accommodated. I was challenged to reach all my students because some came from remote areas with limited or no digital network connection and data.

"Power" and "Settling": Upon reflection, I realised that we were renegotiating our position as new power relations were generated between the impact of the virus and what we perceived as normal.

Lost in the jungle: As a teacher educator, I faced unparalleled trials. At first, I was struggling to run away from the chaos. I was conscious of my duty to establish innovative instructional programmes and routines, but the sudden transition from in-person teaching to remote learning was daunting. I was experiencing diverse emotions along this journey as I questioned and revisited my pedagogical approach. Finally, I realised that I needed to work together with my students, colleagues, and critical friends to help me devise alternative ways of effective teaching. They were the people who would help me find my way out of the jungle.

Makie's Narrative About the Images and Texts in the Collage

Adaptor: The image of the adaptor in my collage is that of the iDapt multi-charger. It simultaneously charges multiple (up to four) devices and saves time and electricity. It is indicative of the multi-tasking we had to engage in when teaching remotely, and the numerous workshops and meetings we had to attend to help us during the lockdown period.

"A touch of sunshine": These words and the picture of dogs pulling a sleigh together illustrate that we can achieve something only if we work together. We felt overwhelmed, and we had to understand our feelings and learn to cope under the circumstances.

"Our emotions": That sensation is also captured by this phrase, The Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdown regulations engendered a sense of loneliness. However, the learning that was generated by collaboration comforted and supported us.

"It's just an amazing feeling": This phrase captures the sense of achievement I felt when I was successful.

"A space to reimagine": These words demonstrate that we had to quickly use digital platforms and be more creative than ever before.

We deemed collage-making to be an all-encompassing learning activity because we could express ourselves freely without fear of criticism or ridicule. It also introduced new parts of ourselves that we had not been aware of before. After intensive discussion and reflection, we collaboratively developed a concept map.

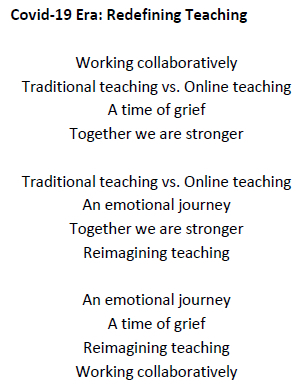

Concept Mapping

Chamberlain (2015) described concept mapping as a graphical illustration of information that links different concepts using arrows. According to Butler-Kisber and Poldma (2010), concept mapping is a stimulating strategy qualitative researchers use to make sense of their data and keep track of interpretations as they begin to emerge. It is mainly helpful for "documenting the relational aspects of initial data interpretations" (Butler-Kisber & Poldma, 2010, p. 6). Concept mapping is particularly suitable for qualitative work because it maintains and reinforces qualitative underpinnings and helps to reduce data. We created a concept map (Image 3) by perusing the transcripts of our collage presentations. We circled keywords and phrases that were significant for our learning experiences in this process. We then grouped these words and phrases according to what belonged together.

Like collage making, the mapping process can yield a visual reformulation of ideas with text condensed to keywords and phrases, arranged and linked using sketched shapes (Butler-Kisber & Poldma, 2010). Furthermore, the mapping process strengthens data analysis and aids in developing an enhanced conceptual understanding of the phenomenon under study (Vaikla-Poldma, 2003). Creating this concept map allowed us to reexamine our thoughts and illuminate the understanding and meaning making of our ideas and thoughts.

Poetry

Researchers around the globe have used poetry for different purposes. According to van Schalkwyk (2010), a prevalent application of poetry is its use as a tool of data presentation and representation. In their self-study project, Hamilton and Pinnegar (2013) used poetry to examine their thinking and understanding of collaborative practice. They developed the drive to "push the boundaries of their data analysis process by using both metaphor and poetry" (Tidwell & Jónsdóttir, 2020, p. 33). Our investigation yielded a pantoum poem using the concepts and phrases captured in the concept map to represent and present our shared discoveries.

A pantoum is composed by repeating lines meaningfully. Furman et al. (2006, p. 28) described the pantoum as "a French poem based on Malaysian forms" arranged so that each stanza's second and fourth lines are repeated as the first and third lines of the next stanza. We created the pantoum express both our frustrations and our sense of achievement when teaching using digital platforms. In addition, the process allowed us visualise our shared experiences in a single but mutually created piece.

We found this poetic form reflective of our research and teaching practice, and a valuable and fundamental tool to express our understandings. Using the poem uncovered pivotal themes and assisted us in seeing beyond what mere data presentation in the discursive text could offer. As a result, the poem emphasises the reoccurring themes that encouraged us to work collaboratively during the Covid-19 pandemic. Below is the pantoum we composed.

By crystallising our working experiences, this pantoum represents our deepest emotions and dilemmas, and illuminates our learning journey.

Discussion

We employed thematic analysis to analyse the data obtained through the arts-based media that we employed. Braun and Clarke (2006) emphasised that researchers need to ensure that their interpretations and analytical arguments are in line with the data excerpts in thematic analysis. We thus checked and re-checked our interpretations of the collages, the concept map, and the pantoum poem to ensure they addressed the topic under investigation. Thus, we developed the following themes from the patterns within the data: navigating relationships virtually, accommodating diversity, openness and vulnerability, and creating shared spaces.

Navigating Relationships Virtually

We wanted to engage in collaborative learning to positively navigate relationships among and with our students, and encourage perseverance in facing the challenges we all experienced during the pandemic. We realised that learning institutions exercise all-embracing power concerning social, emotional, and academic development. Luthuli (2021) expressed that classrooms and schools should be places of emotional security and affirmative relationships to influence learners' attitudes and an optimistic mindset. We participated in social change and turned our virtual classrooms into spaces that promoted learning facilitated through collaboration, communication, creativity, innovation, empathy, and respect. Looking back, we comprehended that we were negotiating power relations between the impact of the virus and what we perceived as being normal.

Through our interactive pedagogies, we attempted to support students through teaching and supervision. As teacher educators, we wanted our students to remain enrolled, knowing that our support and creative learning would sustain them despite having to face sudden unanticipated changes and sensitive responsibilities such as social distancing, masks, and sanitising for vulnerable students. Even with these measures in place, as teacher educators, we were mindful that inequalities lingered- predominantly for students living in remote places and from underprivileged households where internet access was often insufficient. We realised the need for supportive, collaborative, and reciprocal communities of practice within our virtual learning communities. There was great concern regarding re-imagining teaching and learning to harvest opportunities for the understanding of shared knowledge, collaboration, co-creation, and involvement. Our collaborative narrative for teaching and learning introduced us to social emotional values and to the importance of inclusivity, engagement, and collaboration. Embracing asynchronous teaching and learning was also important because many of our students were household heads or young parents themselves, who were parenting infants and young children at home with no assistance while living under non-conducive conditions.

Samaras (2011) stated that self-study research requires working collaboratively with a critical friend or friends. She elucidated that critical friends hearten us and ask questions so we can adopt diverse perspectives. They also assist us in validating our self-study research. We thus acknowledge that the teaching and learning journey was not an unaccompanied one but that one needed the collaboration and support of critical friends. We gratefully learned to be each other's sounding board and pillar of support. How we negotiated the online process will be discussed in a subsequent section.

Accommodating Diversity

In the face of the pandemic, we were mindful of our students' backgrounds and challenges, and we critically thought about accommodating them all. Kidd and Murray (2020) highlighted that teaching online requires insight into the diversity of students' surroundings and how that impacts learning. They mentioned, for example, childcare and domestic responsibilities, privacy, and the number of family members who share connecting devices. We thus employed learning platforms that accommodated our students' diversity and needs. For example, in her postgraduate module, Ntokozo uploaded videos to Dropbox and Moodle for students who could not attend Zoom or WhatsApp sessions due to personal or technical issues. The university provided the students with data, and students who were funded were also given laptops to support their online learning.

We learned more about different teaching and learning platforms that could accommodate students from all socioeconomic backgrounds. While working with students from diverse backgrounds, we realised that we also shaped our professional learning. Aligned with Weare (2004), professional learning had to be continuous and required feedback and reflection on what was being learned or assessed. Reflecting on our teaching learning prepared us to find solutions to the challenges we encountered. Similarly, Easton (2008) highlighted that "professional learning requires a new action plan for systems that are engaged in improving so that all children [students] can learn" (p. 756). We needed to become knowledgeable about our teaching and use insight to connect with our students through multiple digital platforms such as Moodle, WhatsApp, and email. It was challenging to reach all our students because were in remote areas with poor or limited network connections.

And, as Khau (2021) has alluded to, worldwide education systems were contending with online learning challenges such as cyber security, technical glitches, data costs, connectivity issues, social exclusion, depression, and lack of human contact. For example, Ntokozo tried to interact with her students via Zoom meetings on numerous occasions. After many failed attempts and poor attendance due to a lack of data, poor connectivity, and load shedding, Makie suggested she rather conduct her lessons via WhatsApp and email. Ntokozo thus grasped the need to unlearn old ways of teaching and to learn new ways. In this manner, she engaged in self-development for the benefit of her students. She explored different platforms to reach her students and accommodated their diversity as she shifted from Zoom meetings to WhatsApp sessions.

In this regard, we also learned an important lesson. As teacher educators, we initially wanted to adopt the most sophisticated communication platforms (Zoom and Moodle) because their use seemed professional and was what others at better equipped institutions employed. However, as we came to understand our students' backgrounds and diversity, the least sophisticated platform (WhatsApp, which was utilised by the majority of the students) was used and became the most effective means of communication.

Openness and Vulnerability

Vulnerability is a unique characteristic of self-study research. Berry and Russell (2016) asserted that self-study researchers must thoughtfully make themselves vulnerable and open in their study. The theme of openness and vulnerability thus iterates our feelings and approach during this research process. As we shared our experiences of teaching remotely, we realised that it was an exhausting task. We found ourselves working on our computers seven days a week. Students were constantly sending messages on WhatsApp, and emails asking for clarity on assignment requirements, while others asked for extensions because they had missed due dates for their assignments. We felt obliged to respond to them even during weekends because we understood their predicament. We sometimes felt alone and thought: "We did not sign up for this!" At the same time, we understood that the Covid-19 pandemic had affected everyone. Many conflicting emotions surfaced. We were anxious and frustrated but told ourselves that we should be thankful that we still had jobs given that many people lost their jobs during that time. We strove to succeed and assist our students to the best of our ability.

Creating a Shared Space

As teacher educators working at the same institution, we decided to create a space to share our teaching experiences. Dinkelman (2011) has argued that teacher educators who work together can create planned inquiry spaces centred on their practices to make sense of their setting. We established Zoom meetings and met on this online platform twice a month. As we encountered more challenges, we met once a week. In some instances, teaching became inefficient because most students were from rural settings, computer illiterate, and had little access to technology and the internet. We discussed during these meetings how we could assist students who could not access the learning platform, Moodle. Makie indicated that WhatsApp worked well when she had a small group but was unsure how to use it with a larger number of undergraduate students. On deliberation, we thought it would be best if Makie divided her students into groups, and so she created three WhatsApp groups so all her students could be accommodated. The teacher educators at our institution were advised to use asynchronous teaching so no student was left out. Our students could access notes, slides, and audio recordings posted on WhatsApp. Creating a shared space helped us manoeuvre this terrain by sharing and bouncing ideas on what might work. These meetings became our learning spaces where we felt we overcame the difficulties we faced. Working collaboratively made us believe that there was a glimmer of hope.

It is acknowledged that not all our students were engaged all the time, initially. However, we encouraged the involved students to use their connections to engage others. In this manner, all the students who persevered were eventually connected.

Trustworthiness and Credibility

Ensuring trustworthiness and credibility is an essential aspect of qualitative research (van Schalkwyk, 2010). Narrative inquiry is explained as attending to the ethical issues of voice and power by turning a study inward and making the researcher and participant the same (Clandinin, 2013). We have presented a comprehensive and detailed account of how the data were generated and represented. We also offer evidence of the value of working collaboratively to improve our teaching practice.

We met weekly via Zoom meetings to deliberate on issues faced by teacher educators during the Covid-19 pandemic. We made a point of engaging our critical friends in order to share their insights and help identify alternative ways to improve our practice. For example, as Creswell (2009) explained, qualitative validity has to share precise details based on research. In this regard, we documented our research process in as much detail as possible. In addition, Creswell (2009) highlighted that validity strengthens qualitative research, and it is grounded in determining whether the findings are truthfully presented by researcher and participant, and meaningfully interpreted by the reader. Similarly, Feldman (2003, p. 27) suggested that "we can increase the validity of our self-studies by paying attention to and making public the ways [in which] we construct our representations of our research."

Implications and Limitations

As teacher educators, we continue to face unparalleled trials. We are not running away from the chaos but are fighting together on a united front. We are conscious of establishing instructional programmes and routines to cope with the sudden transition from in-person teaching to remote learning. We have also experienced diverse emotions, and questioned and revisited our pedagogical approaches throughout this journey. We realise that the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic taxed us emotionally, and now we ponder our face-to-face engagement with people. We certainly missed our interactive conversations in the classroom and long for the chaotic moments that resulted in organised ideas and thoughts.

We felt isolated during our study's initial stages due to social distancing requirements and ambiguities about personal safety and health. But although it was challenging to maintain an optimistic mindset during the pandemic, we realised that we had an opportunity to reflect on how to employ teaching practices that hearten teacher educators and shape and strengthen human relationships in our particular educational context. We envisage that the outcomes of this research project will encourage teacher educators to be cognisant of learning outcomes, and that they will be motivated to develop strategies that will drive student learning and sustain teaching and learning opportunities so that everyone feels accepted accommodated.

While creating our collages, we experienced a hive of emotions that obliged us to rethink our position as teacher educators. We aspired to explore new ways of learning and to adopt a positive mindset. We also realised that we would be nurtured by forging relationships with colleagues who had experienced what we went through, and this was indeed a great source of support and comfort. This sentiment was also reflected by Carrillo and Flores (2020), who stated that interactions with online learning communities provide teachers and teacher educators with valuable support for peer collaboration and increased reflection in their everyday practice.

The study was limited because we did not explore our students' authentic online learning experiences. We also did not consider their assessment outcomes in order to determine the effectiveness of our online teaching efforts. A follow-up project will address these components for a more holistic view of the topic. Another limitation was that we engaged online with colleagues from our institution, only. Creating learning communities involving teacher educators from other similar institutions and study fields is thus envisaged.

Conclusion

This study highlighted how changes in the academic environment during the Covid-19 era forced us to quickly adapt and improve our pedagogic practices. We made every effort to be capacitated to drive our students' learning and ensure their academic success in 2020, despite the disruption of the academic year. Working collaboratively engendered a deep understanding of the possibilities of positive change in educational delivery. This change resulted in novel and unparalleled lived experiences that taught us more about who we are and who we have to become.

Furthermore, our study confirmed that working collaboratively as teacher educators, as advocated by the sociocultural perspective, can build a strong learning community where all members are valued, and healthy relationships are cultivated. We learned that positive learning experiences are generated when we listen emotively, adapt our practice to digital teaching, and reflect honestly on our daily adventures and challenges. This approach has significant implications for teaching and learning during a pandemic. However, the impact of remote teaching on students' learning still seems understudied and needs to be addressed.

Using a narrative inquiry design has engendered an enriched understanding of the lives of teacher educators who need to navigate their personal and professional knowledge landscapes in a novel and unexpected context. The study encouraged student participation, regardless of their diverse social backgrounds, and inspired our ability to link arts-based research with teacher education and digital platforms. This approach was redemptive because it provoked amended perspectives and triggered exhilarating possibilities for teaching and learning remotely, which will be addressed in a follow-up project. Moreover, teacher educators might feel a sense of healing through engaging other people in their teaching practice and utilising various artistic methods to understand and promote teaching and learning. The findings of this narrative inquiry study, which employed an arts-based approach, are intriguing and will hopefully motivate other teacher educators to utilise comparable methods. We hope the study will afford teacher educators new insights into the need to embrace social change and accept the new normal in education.

In conclusion, the value of learning from one another is pivotal in education. In this self-study project, the arts-based media we employed enhanced our responsiveness, and highlighted the importance of recognising others in educational research. Therefore, we recommend collaborative teaching and the sharing of experiences among teacher educators in order to constantly reimagine and reshape teaching and learning in the higher education context in the post-Covid-19 pandemic era.

References

Banks, J. A., Cookson, P., Gay, G., Hawley, W. D., Irvine, J. J., Nieto, S., Scholfield, J. W., & Stephan, W. G. (2001). Diversity within unity: Essential principles for teaching and learning in a multicultural society. The Phi Delta Kappan, 83(3), 196-203. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/003172170108300309 [ Links ]

Berry, A., & Russell, T. (2016). Self-study and vulnerability. Studying Teacher Education, 12(2), 115-116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2016.1197498 [ Links ]

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Butler-Kisber, L., & Poldma, T. (2010). The power of visual approaches in qualitative inquiry: The use of collage making and concept mapping in experiential research. Journal of Research Practice, 6(2), 1-16. http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/197/196 [ Links ]

Carrillo, C., & Flores, M. A. (2020). Covid-19 and teacher education: A literature review of online teaching and learning practices. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 466-487. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1821184 [ Links ]

Chamberlain, R. P. (2015). Using concept maps in political science. Journal of Political Science Education, 11(3),347-357. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2015.1047103 [ Links ]

Childs, M., Mapasa, T., & Ward, M. (2020). Considering craft- and arts-based practitioner inquiry activities as a prompt for transforming practice. Educational Research for Social Change, 9(2), 81-100. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2020/v9i2a6 [ Links ]

Clandinin, D. J. (2013). Engaging in narrative inquiry. Left Coast Press.

Clandinin, D. J, & Connelly, E. M. (1998). Asking questions about telling stories. In C. Kridel (Ed.), Writing educational biography: Explorations in qualitative research (pp. 245-253). Routledge

Clandinin, D. J., Pushor, D., & Orr, A. M. (2007). Navigating sites for narrative inquiry. Journal of Teacher Education, 58, 21-35. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0022487106296218 [ Links ]

Crawford, J., Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, J., Malkawi, B., Glowatz, M., Burton, R., Mangni, P. A., & Lam, S. (2020). Covid-19: 20 countries' higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 3(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2020.3.1.7 [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE.

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12365/17357/46%20Effective_Teacher_Professional_Development_REPORT.pdf?sequence=1

Dinkelman, T. (2011). Forming a teacher educator identity: Uncertain standards, practice, and relationships. Journal of Education for Teaching, (37)3, 309-323. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2011.588020 [ Links ]

Easton, L. B. (2008). From professional development to professional learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 89(10), 755-756. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/003172170808901014 [ Links ]

Easton, L. B. (2012). Principles of design energize learning communities. The Learning Professional, 33(4), 49. https://www.proquest.com/openview/938c9ec2898ef4ad3d64e6b457715fb5/1.pdf?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=47961 [ Links ]

Feldman, A. (2003). Validity and quality in self-study. Educational Researcher, 32(3), 26-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032003026 [ Links ]

Ford, E. (2020). "Tell me your story": Narrative inquiry in LIS research. College & Research Libraries, 81(2), 235-247. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.8L2.235 [ Links ]

Furman, R., Lietz, C. A., & Langer, C. L. (2006). The research poem in international social work: Innovations in qualitative methodology. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(3), 24-34. http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/53/PDF/furman.pdf [ Links ]

Gerhard, G., & Mayer-Smith, J. (2008). Casting a wider net: Deepening scholarship by changing theories. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning, 2(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2008.020120 [ Links ]

Hamilton, M. L., Smith, L., & Worthington, K. (2008). Fitting the methodology with the research: An exploration of narrative, self-study and auto-ethnography. Studying Teacher Education, 4(1), 17-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425960801976321 [ Links ]

Hamilton, M. L., & Pinnegar, S. (2013). A topography of collaboration: Methodology, identity and community in self-study of practice research. Studying Teacher Education, 9(1), 74-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2013.771572 [ Links ]

John-Steiner, V., & Mahn, H. (1996). Sociocultural approaches to learning and development: A Vygotskian framework. Educational Psychologist, 31(3/4), 191-206. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Holbrook-Mahn/publication/229721092_Sociocultural_Contexts_for_Teaching_and_Learning/links/5d718dc4a6fdcc9961b1fc2f/Sociocultural-Contexts-for-Teaching-and-Learning.pdf [ Links ]

Khau, M. (2021). After the rain comes the sun: Hope, faith, and healing in a wounded world [Editorial]. Educational Research for Social Change, 10(2), viii-xi. http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/ersc/v10n2/01.pdf [ Links ]

Kidd, W., & Murray, J. (2020). The Covid-19 pandemic and its effects on teacher education in England: How teacher educators moved practicum learning online. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 542-558. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1820480 [ Links ]

Korthagen, F. (2017). Inconvenient truths about teacher learning: Towards professional development 3.0. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 23(4), 387-405. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1211523 [ Links ]

Kortjass, D. L. P. (2020). Cultivating an integrated learning approach to early childhood mathematics: A teacher educator's self-study [Doctoral thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa]. University of KwaZulu-Natal Research Space. https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/handle/10413/19948 [ Links ]

Lahman, M. K. E., Taylor, C. M., Beddes, L. A., Blount, I. D., Bontempo, K. A., Coon, J. D., Fernandez, C., & Motter, B. (2020). Research falling out of colorful pages onto paper: Collage inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(3-4), 262-270. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800418810721 [ Links ]

Luthuli, K. (2021). Using photographs and memory-work to engage novice teachers in collaborative learning about their influence on learner behaviour. Educational Research for Social Change, 10(2), 142-160. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2021/v10i2a9 [ Links ]

Masinga, L., Myende, P., Marais, A., Singh-Pillay, A., Kortjass, M., Chirikure, T., & Mweli, P. (2016). "Hear our voices": A collective arts-based self-study of early-career academics on our learning and growth in a research-intensive university. Educational Research for Social Change, 5(2), 117-135. https://www.proquest.com/openview/a6933e68ca3f1bfab03dcc845ce3d7b1/1.pdf?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2037364 [ Links ]

McMurtry, A. (2015). Liked your textbook . . . but I'll never use it in the courses I teach. Teachers' College Record Newsletter. https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=0azB5pIAAAAJ&citation_for_view=0azB5pIAAAAJ:8k81kl-MbHgC

Mkhize, N. S. (2020). Exploring social and emotional learning in my Grade 4 classroom: A teacher's self-study [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. [ Links ]

Murphy, P., & Ivinson, G. (2003). Pedagogy and cultural knowledge: A sociocultural perspective. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 11(1), 5-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681360300200157 [ Links ]

Neuwirth, L. S., Jovic, S., & Mukherji, B. R. (2020). Reimagining higher education during and post-Covid-19: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 27(2), 141-156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477971420947738 [ Links ]

Northfield, S., & Sherman, A. (2004). Acceptance and community building in schools through increased dialogue and discussion. Children & Society, 18(4), 291-298. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/chi.788 [ Links ]

Peters, M. A., Rizvi, F., McCulloch, G., Gibbs, P., Gorur, R., Hong, M., Y, Hwang., L,Zipin., M., Brennan, S., Robertson, Quay., J, Malbon, D.,Taglietti., R. Barnett., W, Chengbing.,P., McLaren., R, Apple., M., Papastephanou., N., Burbules,. L., Jackson., P., Jalote., M., ... et al. Misiaszek, L. (2020). Reimagining the new pedagogical possibilities for universities post-Covid-19: An EPAT collective project. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 1-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1777655

Pillay, D., Ramkelewan, R., & Hiralaal, A. (2019). Collaging memories: Reimagining teacher-researcher identities and perspectives. In K. Pithouse-Morgan, D. Pillay, & C. Mitchell (Eds.), Memory mosaics: Researching teacher professional learning through artful memory-work (pp. 77-93). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97106-3_5_77

Samaras, A. P. (2011). Self-study teacher research: Improving your practice through collaborative inquiry. SAGE.

Samaras, A. P., & Freese, A. R. (2006). Self-study of teaching practices primer. Peter Lang.

Samaras, A. P., Karczmarczyk, D., Smith, L., Woodville, L., Harmon, L., Nasser, I., Parsons, S., Smith, T., Borne, K., Constantine, L., Mendoza, E. R., Suh, J., & Swanson, R. (2014). A pedagogy changer: Transdisciplinary faculty self-study. Perspectives in Education, 32(2), 117-135. https://www.proquest.com/openview/c7f2139b72cd7584a36bdfa2799c3f74/1.pdf?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2031892 [ Links ]

Tidwell, D. L., & Jónsdóttir, S. R. (2020) . Methods and tools of self-study. In J. Kitchen, A. Berry, S. M. Bullock, A. R. Crowe, M. Taylor, H. Guôjónsdóttir, & L. Thomas (Eds.), 2nd International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education (pp. 1-50). Springer.

Vaikla-Poldma, T. (2003). An investigation of learning and teaching processes in an interior design class: An interpretive and contextual inquiry [Unpublished doctoral dissertation). McGill University, Canada. [ Links ]

van Schalkwyk, G. J. (2010). Collage life story elicitation technique: A representational technique for scaffolding autobiographical memories. The Qualitative Report, 15(3), 675-695. http://dx.doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2010.1170 [ Links ]

Weare, K. (2004). Developing the emotionally literate school. SAGE.

1 Protocol reference numbers: HSS/0060/017D & HSS/0095/018D