Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Educational Research for Social Change

versión On-line ISSN 2221-4070

Educ. res. soc. change vol.12 no.1 Port Elizabeth abr. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2023/v12i1a2

EDITORIAL

Parent-Practitioner Collaboration to Support Sustainable Development in Early Years Education1

Stef EsterhulzenI; Martie UysII; Nomsa MohoshoIII

INorth-West University Stef.Esterhuizen@nwu.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5321-9570

IINorth-West University Martie.Uys@nwu.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5470-5722

IIINorth-West University, Nomsa.Mohosho@nwu.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4354-7439

ABSTRACT

This article stems from a research project in five early childhood development (ECD) centres in South Africa, and focuses on parent-practitioner collaboration for sustainable development in early years education. Using a qualitative approach, we followed a participatory action learning and action research (PALAR) design to answer the main research question: "How can parent-practitioner collaboration support education for sustainable development in the early years?" Participants formed an action learning set (ALS) in which they acted as co-researchers and equal partners to construct their own meanings in order to advocate for social change. Data were collected in the ALS during Cycle 3 of the PALAR process. We relied on transcribed, recorded ALS discussions and photovoice activities to generate data, and used thematic content analysis to collaboratively analyse the data. Our findings disclose that education for sustainable development is possible when parents and practitioners collaborate.

Keywords: education for sustainability, parent-practitioner collaboration, participatory action learning and action research (PALAR), posthumanism, transformative learning theory

Background to the Study

Young children globally, are the most vulnerable in the face of educational, socioeconomic, health, environmental, and political threats (Koen, 2021). In South Africa, the history of apartheid, together with the subsequent socioeconomic inequalities and detrimental impact of Covid-19 on the early childhood (ECD) sector, have adversely affected most South African children and deprived them of their basic rights to health care, education, social services, and nutrition (Ashley-Cooper et al., 2019). Globally, governments have recognised the urgency for sustainable development through ending poverty and inequality, protecting the planet, and ensuring that all people live in healthy, just, and prosperous environments (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO], 2014).

Education is regarded as one of the main tools to establish sustainable futures for young children (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2015), and education for sustainability (EfS) attends to the need for quality education that provides opportunities to acquire knowledge, skills, values, and behaviours necessary for a sustainable future for all (Borg & Pramling Samuelsson, 2022). ECD focuses on children from birth to 7 years of age (Republic of South Africa, n.d.) and is linked to sustainable development because quality education-which is founded on a strong ECD sector- strengthens individual, social, economic, and environmental quality (Ruto-Korir et al., 2020). Early childhood EfS is, therefore, a key enabler of sustainable development (Borg & Pramling Samuelsson, 2022) and is considered an essential means of creating sustainable building blocks for adult lives (Warwick et al., 2018). Thus, the necessity to begin change for a more sustainable world and better future as early as the early childhood years (Borg & Pramling Samuelsson, 2022; Engdahl, 2015).

Quality education in the early years rests on three elements, namely, the family, the school, and the community, and it is therefore beneficial to connect learning to these three elements (Hu & 0degaard, 2019). Active collaboration between parents, practitioners2, and caregivers is important for sustainable development, and research has shown that parental involvement in education benefits the child, parents, and practitioners (Ntekane, 2018). Furthermore, positive parent-practitioner collaboration can enhance adults' knowledge and understanding of children and their learning opportunities. This, in turn, may contribute to children's academic performance, social competencies, emotional well-being, and even improve school attendance (Al-Hail et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2020).

The preceding discussion indicates that a sustainable future requires focused attention on parent-practitioner collaboration for sustainable development (Georgeson, 2018). And, against this backdrop, researchers from the North-West University (NWU) embarked on a research project involving parents and practitioners in five ECD centres in the Sedibeng East District, Vereeniging, Gauteng, South Africa.

This paper explores whether parent-practitioner collaboration could support sustainable development in early years education.

Literature Review

Initially, EfS was divided into three dimensions, namely, the ecological (biophysical), economic (poverty reduction), and social/cultural (social justice) components (Boldermo & 0degaard, 2019), with the main focus being on the ecological (or environmental) dimension (Davis & Elliot, 2014). These dimensions of ecology, economy, and social/cultural aspects stem from the Brundtland Report, which described sustainable development as "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (Brundtland, 1987, p. 292). A fourth dimension, good governance, has since been added to these despite its overlap with the social/cultural dimension (Hagglund & Johansson, 2014). All four dimensions are important for EfS, which needs to go beyond its focus only on environmental education (Grindheim et al., 2019).

EfS is critical for sustainable development because it improves quality of life; increases social awareness, tolerance, and justice; enhances creativity and innovation; includes capacity-building; improves public awareness; and aims to create literate and responsible citizens (Laurie et al., 2016). EfS involves an interdisciplinary approach that teaches children to learn from each other, cooperate, make decisions, take responsibility, and consider the consequences of their actions. As part of life-long learning, EfS enables parents, practitioners, and children to transform their thinking, make conscious decisions, and accept responsibility for social, economic, and environmental sustainability (Borg & Pramling Samuelsson, 2022). Transformative learning theory (Mezirow, 2000) and posthumanism (Blaikie et al., 2020) encourage changed perspectives and heightened awareness of the environment and other living beings involved with the individual. The literature has recognised context and education's significant influence on child development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Mahlomaholo et al., 2022). Posthumanism affirms that difficulties do not exclusively lie within the young child alone but are influenced by the child's relationships with other people, animals, the environment, and, ultimately, with the planet (Mahlomaholo et al., 2022). Teaching in the early years can no longer only be seen as the transference of knowledge from adult to child, but should provide ample opportunities for change, growth, and development in which children are taught a variety of skills necessary to create sustainable futures for themselves (Mahlomaholo et al., 2022). Early childhood education and care for sustainability are necessary to break the cycles of poverty, decline, and inequality (UNDP, 2015), as well as to change skills, values, and behaviours (Mahlomaholo et al., 2022). The literature asserts that young children who have been exposed to quality early childhood education and care for sustainability will mature into good, democratic, and productive citizens (Mahlomaholo et al., 2022) who are caring, capable, and responsible (Warwick et al., 2018)-all of which are characteristics that can contribute to sustainable development. This correlates with the transformative learning theory (Mezirow, 2000) and posthumanism agendas to adjust human perspectives, intellectual, physical, and psychological capacities towards diminishing discrimination against other humans, nonhumans, nature, the environment, and beyond-and to revise our thoughts and practices to bring about social change (Andersson, 2022; Blaikie et al., 2020).

Research has shown that parental involvement is an inseparable part of a child's development, and promotes continuity in learning and improves children's overall performance at school and beyond- thus, leading to sustainable development (Durisic & Bunijevac, 2017; Lunga et al., 2022). When there is a partnership between parents and practitioners, improved academic performance is achieved (Epstein, 2009). Young children should be exposed to a safe, supportive, and healthy home and school environment where appropriate learning experiences take place to promote sustainable development (Durisic & Bunijevac, 2017). Parents, as the primary caregivers of young children (Jeong et al., 2021), should be responsive to promoting sustainable development. Recent evidence has revealed that parenting intervention improves cognitive, language, motor, and socioemotional development and attachment aspects in the early years and reduces behaviour problems (Jeong et al., 2021). Parents, as their children's first teachers, are valuable resources and are key in shaping children's characters. The development of children's personalities, self-image, values, and attitudes are greatly influenced by parents and significant others such as practitioners (Department of Basic Education, 2011). This is also in line with transformative learning theory and posthumanism, which view transformation in early years education as possible when stakeholders such as parents and practitioners collaborate and regard children as being interwoven with, and responsible for, the life and habitat of all living creatures, the environment, and the planet (Mahlomaholo et al., 2022).

Although many parents recognise the importance of parental involvement, few participate in or volunteer for school activities. They seldom visit the school, classroom, or practitioners due to job-related responsibilities, ignorance, lack of motivation, working hours, and other personal reasons (Al-Hail et al., 2021). Parent-practitioner collaboration is one of the key factors in EfS (Al-Hail et al., 2021) and directly influences the quality of children's learning, socioemotional, and moral dimensions. Parents and practitioners should find a way to collaborate to ensure sustainable futures for young children because this enables the children to grow and develop to their full potential. And would result in enhanced academic performance and lower absenteeism, repetition, drop-out rates, and diminished need for expensive remediation to address developmental delays and socioeconomic challenges later in life (Atmore et al., 2012). This is essential for equipping future generations with skills to understand sustainability challenges, encourage resilience, and accept social change towards sustainable thinking and living (UNESCO, 2014).

In this paper, transformative learning theory linked with posthumanism was used as the theoretical approach to orientate the research project and guide us on aspects that could contribute to parent-practitioner collaboration to support sustainable development in the early years.

Theoretical Framework

Transformative learning theory initiates change in people's thinking patterns and aims to make them aware of their feelings, perceptions, and understandings. Mezirow (2000) believed that adults are able to acquire an enhanced level of awareness about their upbringing, experiences, education, beliefs, feelings, and assumptions. They can evaluate these, and negate or synthesise old perspectives in favour of new ones to fit into the broader context of their lives. Thus, adults can critically review and reflect on past experiences to transform their understanding. Wang et al. (2019) described the concept of transformative learning as a radical change in individuals' perspectives and views of the world that subsequently shapes their behaviour. Transformative learning is a process in which people reflect on their actions, which causes them to change their thinking and reach a different understanding of an experience (Wood, 2020). Transformative learning theory can serve as a tool for action to support parent-practitioner collaboration for sustainable development by understanding how practitioners and parents can work together. Most parents do not feel comfortable approaching practitioners at school, much less collaborating with them (Al-Hail et al., 2021). Transformative learning theory can help address practitioners' and parents' perceptions of collaboration for sustainable development in the early years by changing their thoughts, feelings, and actions. Our action learning set (ALS) interacted continually during this project, and participants were regarded as co-researchers. Mutual respect for each participant's diverse views, opinions, and insights led to knowledge about parents' and practitioners' views of parent-practitioner collaboration for sustainable education (Al-Hail et al., 2021).

The participants were thus enabled to learn through critical self-reflection by acting on their thoughts and ideas (transformative learning theory) while understanding that learning in the early years not only relies on the individual child but is interwoven with the life and the habitats of all humans, nonhumans, the environment, planet, space, and entities beyond our planet-posthumanism- (Blaikie et al., 2020). Posthumanism regards the ecosystem as an integral part of an individual where the micro-, meso-, exo-, macro-, and chronosystems can significantly impact any other agent or system. Humans and nonhumans influence one another and are not independent of the world around us (Blaikie et al., 2020; Bronfenbrenner, 1979). In education, we must move towards an approach in which we learn to value ourselves, other species, the environment, the planet, and beyond. Therefore, we have to go beyond locating challenges solely in the individuality of the young child and should also consider relationships with adults, peers, nonhumans, the wider community, and the environment (Blaikie et al., 2020) when helping children in the early years to develop holistically. Children should build the capacity to develop into reflexive learners for sustainable development, therefore, parents and practitioners need to consider a physical learning environment where knowledge can be co-created by practitioners, parents, and children (Moss, 2016). This should be a collaborative journey of discovery rather than of content delivery. In our study, parents and practitioners collaborated to support sustainable development.

Within the transformative learning and posthumanism frameworks, participants reflected on parent-practitioner collaboration for sustainable development that could lead to social change-which corroborates Wood's (2020) argument that the transformative paradigm introduces participants to new possibilities while examining the social reality of collaboration. This is in line with the posthumanism view that we can change the way we think about ourselves, other species, the environment, and beyond (Blaikie et al., 2020). Both paradigms advocate for transformation and collaboration for sustainable development.

Research Methodology

This research project used a qualitative approach because our participants constructed meaning and knowledge from their experiences (Bertram & Christiansen, 2020). Within the qualitative research approach, we followed a participatory action learning and action research (PALAR) design because our focus was on how parent-practitioner collaboration could support sustainable development in early years education. A PALAR design promotes participant collaboration when reflecting on the research questions (Wood, 2020). The ECD practitioners, parents, and NWU researchers acted as co-researchers in collaborative meetings and therefore formed an action learning set (ALS) in which all discussions, data generation, and analysis took place (Wood, 2020).

Context of the Study

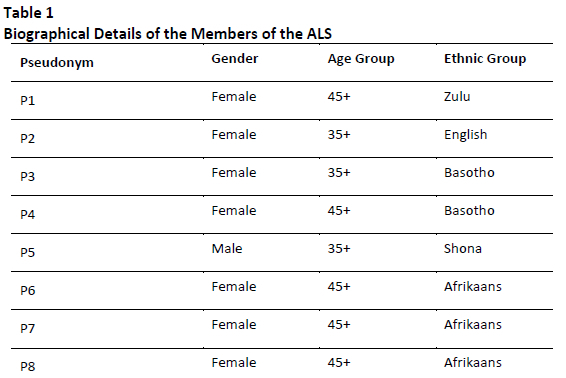

An isiZulu-speaking Grade R facilitator from the National Department of Basic Education in the Sedibeng East District, Vereeniging, Gauteng, acted as the gatekeeper for this project. Her role was to purposively select participants, negotiate, and act as an objective mediator to enhance trust among the members of the ALS and ensure objectivity, as suggested by Wood (2020). The ALS consisted of eight co-researchers, as detailed in Table 1.

Although this study comprised three iterative cycles of action and reflection in which we addressed the research questions as discussed in Lunga et al. (2022), this paper only reports on Cycle 3. During Cycle 3, we developed guidelines for strengthening parent-practitioner collaboration in education for sustainable development. During our discussions, the need for parent-practitioner collaboration to strengthen the capacity for play-based learning became clear. Therefore, we conducted four online sessions, each lasting between 45 and 60 minutes, to assist the ALS to think of ways to promote parent-practitioner collaboration. The reason for conducting online sessions was due to time and distance constraints. We generated the data for Cycle 3 through photovoice, and recorded and transcribed all the discussions.

Research Design

With a qualitative approach as our point of departure, PALAR was utilised as research design to allow us to engage in mutually reinforcing partnerships between researchers, practitioners, parents, and others with inside knowledge or lived experiences to co-construct knowledge (see Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020; Wood, 2020; Zuber-Skerritt, 2019). The NWU researchers' theoretical and methodological expertise, combined with community members' real-world knowledge and practical experiences, could enhance the quality of the research and bring about crucial change for social justice in our communities that could contribute to sustainable development. Zuber-Skerritt (2019) stated that PALAR heightens sustainability due to participants' engagement in developing their skills and knowledge. This occurs as the participants realise the significance of collaboration and caring for others-humans, nonhumans, the environment, and beyond (Blaikie et al., 2020; Mezirow, 2000; Wood, 2020)-thereby respecting transformative learning theory and posthumanism.

In the ALS, we acted as equal partners while discovering, reasoning, critically thinking about, and reflecting on possibilities to support parent-practitioner collaboration for sustainable development in early years education (Wood, 2020). Any form of participatory action research goes beyond understanding the research problem as all partners within the ALS advocate for change (Wood, 2020). Zuber-Skerritt's (2019) three Rs (relationship, reflection, recognition) were employed to establish participants' collaborative and equal roles. The ALS strove to establish a supportive and trusting relationship by acknowledging and accepting one another's backgrounds. Through continual critical reflection, the ALS ensured that we understood and respected each other's point of view, and provided recognition of the learning generated by participants by listening to and acknowledging one another's viewpoints. We also adopted the seven Cs to bring about change, namely, communication, commitment, competence, compromise, critical self-reflection, collaboration, and coaching (Wood, 2020). Communication was necessary to help establish relationships, ensure dialogue, promote learning, and encourage participants to listen to what was, and what was not, being said. Commitment was needed to ensure that participants accepted their responsibilities as co-researchers. Competence ensured that everyone felt capable of participating in the research. Compromise was necessary for participants' inputs and needs to be respected and valued. Critical self-reflection was crucial to reflect on how participants' feelings, thoughts, and values influenced the research process. Collaboration was obtained by participants working together throughout the research. Coaching was needed as mentoring to support one another to achieve personal and professional development.

Data Analysis and Ethics

For data generation and documentation, we utilised the principles of thematic content analysis according to Braun and Clarke's (2013) six steps or phases. First, the collaborative data generation process required us to familiarise ourselves with the data by obtaining an overview of the collected data. Then we highlighted phrases and sentences using coding, after which we identified themes by categorising patterns in the codes. Thereafter, we reviewed the themes to ensure authenticity. By defining and naming the themes, we ensured they would be easily understood. Lastly, we authenticated the findings with the participants through verbatim quotations.

To ensure the credibility of our data, we applied Herr and Anderson's (2005) quality indicators, namely, outcome validity to establish the extent to which our actions resolved the research problem, process validity that explained how lifelong learning was advanced, democratic validity to ensure all participants were respected and treated equally, catalytic validity to ascertain that transformation took place, and dialogue validity to ensure that reflection took place.

We received ethical clearance and permission to conduct this low risk-level research project from the North-West University and from the Gauteng Department of Basic Education. Because research in PALAR is collaborative and participatory, the participants' responses could be anonymous. Therefore, we ensured anonymity by negotiating ethical issues and respecting the participants' opinions in order to ensure their voices were heard. The participants were well-informed about, and committed to, participating in the project (see Zuber-Skerritt, 2019). They took part voluntarily and completed an ethical agreement before the research commenced. The participants were assured they could withdraw at any time if they felt uncomfortable in the research environment. The gatekeeper was responsible for monitoring all correspondence to ensure validity.

An integrated presentation of our results in response to the research questions addressed in the ALS now follows.

Findings and Discussion

Verbatim statements of the participants (see Table 1) reflect the originality of the information we collected when we addressed the main research question, "How can parent-practitioner collaboration support sustainable development in early years education?" The findings show that sustainable development is possible when parents and practitioners collaborate. Two themes, namely, "'Unapproachable' as a constraint towards strengthened collaboration" and "Changed perspectives as a contributing factor towards collaboration," transpired from the data, as depicted in Figure 1.

Theme 1: "Unapproachable" as a Constraint Towards Strengthened Collaboration

Parent-practitioner collaboration for sustainable development benefits both parents and children. Children who see their parents working closely with practitioners gain self-confidence and improved behaviour and socioemotional skills while experiencing a trusting and secure environment in which they can learn and grow (Al-Hail et al., 2021). According to Llamas and Tuazon (2016), parents can benefit from participating in an early childhood education service. These benefits include enhanced social support and parent learning and development, which may contribute to a sustainable future for families. Research has highlighted that parents play a crucial role in their children's school careers (Segoe & Bisschoff, 2019). However, many parents are not involved in their children's schoolwork because some parents believe that practitioners disregard their knowledge. Both parents and practitioners perceived the other as unapproachable for various reasons. For sustainable development to occur, promoting parent-practitioner collaboration is important. According to Jeong et al. (2021), parent-practitioner collaboration is crucial to enhance parents' knowledge, parenting practices, and the parent-child relationship. It also enables children to develop holistically to their full potential. One of the parents explained her uncertainty about visiting her child's ECD centre as follows:

P3: I feel intimidated by practitioners and the school environment. I do not feel comfortable visiting my child's practitioner.

Despite acknowledging the importance of parental involvement, parents rarely volunteer to participate in school activities. One participant explained that practitioners are distant and unapproachable:

P4: There is no way that I will approach my child's practitioner. Practitioners think that we are not interested in our children's performance. I am involved in my child's learning but cannot find a way to visit the centre.

She took this photo (Image 1) to illustrate how distant, unreachable, and unapproachable she perceived practitioners to be.

According to literature, parent-practitioner collaboration contributes to children's performance, self-confidence, improved behaviour and, ultimately, to education for sustainable development (Jeong et al., 2021). Another participant doubted that her contribution could make a difference in her child's life and did not realise that the home, school, and community should all be involved in promoting EfS (Al-Hail et al., 2021):

P4: I am uncertain how my assistance at the centre can contribute to promoting EfS. Practitioners have all the knowledge. I do not feel confident to go to my child's centre.

Despite evidence that both parents and practitioners believe that positive parent-practitioner collaboration can be meaningful and enhance children's development and academic achievement (Santana et al., 2016), practitioners still perceived parents as uninvolved, critical, judgemental, and not appreciative of their efforts to teach their children and one reported as follows:

P2: Parents are not involved in their children's school performance, because they think only us, the practitioners, are responsible to teach their children. They are always busy and lack motivation to attend meetings at school or volunteer to assist us.

Lunga et al. (2022) suggested that parental involvement is crucial for continuity in learning because it would enhance sustainable development for children. Parent-practitioner collaboration can be viewed as a partnership in which they work closely together and share information and advice about children's education (Adams et al., 2016) with the same goal in mind-to improve children's holistic development and attain sustainable development. Nathans et al. (2020) suggested that any type of involvement could be beneficial because it is difficult for practitioners alone to achieve education for sustainable development. Furthermore, when parents are involved in their children's education, their knowledge of their children's development and sustainable development is broadened.

Theme 2: Changed Perspectives as a Contributing Factor Towards Collaboration

Globally, people have realised the importance of changed behaviour to ensure sustainable development (UNESCO, 2016). Changes in thinking and behaviour correlate with transformative learning theory and posthumanism; thus, humans should be cognisant of the interrelationship between people and the environment (Blaikie et al., 2020; Mezirow, 2000). The participants commented as follows:

P3: For the first time, I realise what my role is as a parent. I understand parent-practitioner collaboration better and will help the practitioner when she asks for my assistance.

P2: I now realise how important parent-practitioner collaboration is to education for sustainable development.

P4: I understand that if I do not help the practitioners, it makes their work difficult and that can influence the children in her class.

The parents had not realised that the home, school, and community form the pillars on which EfS are built. They had perceived them as separate entities and not as a unit. Children should grow up in a supportive home and school environment in order to promote sustainable development (Durisic & Bunijevac, 2017). When participants realised that the home and ECD centres should collaborate, they reported that this had changed their perspective.

P 3: I am relieved. Now I know the practitioner and I am a team.

P1: I am grateful. I think our collaboration will improve education for sustainable development.

Participants agreed that the ALS discussions changed their perceptions with regard to their child rearing, education, beliefs, feelings, and assumptions. Participant 5 showed photos (Images 2 and 3) to illustrate his changed perspective. He explained his initial view on parent-practitioner collaboration to education for sustainable development as full of "weeds" (Image 2) before he had listened to the other participants' views and saw another way to look at parent-practitioner collaboration for education for sustainable development. Then, he noticed the beautiful, coloured buds (Image 3).

Participants reached a consensus that collaboration is valuable and necessary to achieve shared goals. One of the participants (Image 4) demonstrated her changed perspective as follows:

P1: This experience made me happy and excited to see how we all transformed from being unsure at the beginning, and now we cannot wait to collaborate. I understand my parents better!

Limitations

The limitations of this project lie in the fact that the findings cannot be generalised to other contexts due to the extent of the study, which took place in only five ECD centres in the Sedibeng East District in Gauteng. Therefore, the results cannot be applied to the broader South African population. Furthermore, only practitioners, parents, and NWU researchers in this area participated in the project, excluding stakeholders such as nongovernmental organisations and school managers.

Conclusion

The results of this project emphasise the importance of parent-practitioner collaboration to support education for sustainable development in early years education. The PALAR design utilised in this project improved the knowledge of practitioners, parents, and NWU researchers to collaborate in and support education for sustainable development in the early years. The collaborative approach enabled the ALS to plan, take action, reflect, and work together as equal partners in a team. We recommend that ECD centres encourage parent-practitioner collaboration in education for sustainable development, which could benefit parents, practitioners, researchers, and even young children.

Acknowledgements

This work is based on the research supported in part by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa (Grant Numbers: 138065) and ETDP SETA. The Grant holder acknowledges that opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in any publication generated by the NRF-supported research are that of the author(s), and that the NRF accepts no liability whatsoever in this regard.

References

Adams, D., Harris, A., & Jones, M. S. (2016). Practitioner-parent collaboration for an inclusive classroom: Success for every child. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 5(3), 235255. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1106456 [ Links ]

Al-Hail, M. A., Al-Fagih, L., Koç, M. (2021). Partnering for sustainability: Parent-teacher-school (PTS) interactions in the Qatar education system. Sustainability, 13(12), Article 6639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126639 [ Links ]

Andersson, I. (2022). The subject in posthumanist theory: Retained rather than dethroned. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 54(4), 395-403. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1851190 [ Links ]

Ashley-Cooper, M., van Niekerk, L., & Atmore, E. (2019). Early childhood development in South Africa: Inequality and opportunity. In N. Spaull & J. D. Jansen (Eds.), South African schooling: The enigma of inequality (pp. 87-108). https://doi:10.1007/978-3-030-18811-55

Atmore, E., van Niekerk, L., & Ashley-Cooper, M. (2012). Challenges facing the early childhood development sector in South Africa. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 2(1), 12-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v2i1.25 [ Links ]

Bertram, C., & Christiansen, I. (2020). Understanding research: An introduction to reading research (2nd ed.). van Schaik.

Blaikie, F., Daigle, C., & Vasseur, L. (2020). New pathways for teaching and learning: The posthumanist approach. Canadian Commission for Unesco. https://dr.library.brocku.ca/handle/10464/15047

Boldermo, S., & Odegaard, E. E. (2019). What about the migrant children? The state-of-the-art in research claiming social sustainability. Sustainability, 11(2), Article 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020459 [ Links ]

Borg, F., & Pramling Samuelsson, I. (2022). Preschool children's agency in education for sustainability: The case of Sweden. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 30(1), 147-163 https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2022.2026439 [ Links ]

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

Brundtland, G. H. (1987). Our common future: Call for action. Environmental Conservation, 14(4), 291294. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892900016805 [ Links ]

Davis, J., & Elliott, S. (2014). An orientation on early childhood education for sustainability and research: Framing the text. In J. Davis & S. Elliott (Eds.), Research in early childhood education for sustainability: International perspectives and provocations (pp. 1-17). Routledge.

Department of Basic Education. (2011). National curriculum statement: Curriculum and assessment policy statement. Foundation phase.

Department of Higher Education and Training. (2017). Policy on minimum requirements: ECD. https://www.dhet.gov.za

Durisic, M., & Bunijevac, M. (2017). Parental involvement as an important factor for successful education. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 7(3), 137-153. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1156936.pdf [ Links ]

Engdahl, I. (2015). Early childhood education for sustainability: The OMEP world project. International Journal of Early Childhood, 47, 347-366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-015-0149-6 [ Links ]

Epstein, J. L. (2009). In school, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action (3rd ed.). Corwin Press.

Georgeson, J. (2018). Sustainable leadership in the early years. In V. Huggins & D. Evans (Eds.), Early childhood education and care for sustainability: International perspectives (pp. 124-137). Routledge.

Grindheim, L. T., Bakken, Y., Hauge, K. J., & Heggen, M. P. (2019). Early childhood education for sustainability through contradicting and overlapping dimensions. ECNU Review of Education, 2(4) 374-395. https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531119893479 [ Links ]

Hagglund, S., & Johansson, E. M. (2014). Belonging, value conflicts and children's rights in learning for sustainability in early childhood. In J. Davis & S. Elliot (Eds.), Research in early childhood education for sustainability: International perspectives and provocations (pp. 38-48). Routledge.

Herr, K., & Anderson, G. L. (2005). The action research dissertation: A guide for students and faculty. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226644

Hu, A., & 0degaard, E. E. (2019). Play and/or learning: Comparative analysis of dominant concepts in national curriculum guidelines for early childhood education in Norway, Finland, China, and Hong Kong. In A. W. Wiseman (Ed.), Annual review of comparative and international education 2018 (Vol. 37, pp. 207-224). Emerald Publishing.

Jeong, J., Franchett, E. E., Ramos de Oliveira, C. V., Rehmani, K., & Yousafzai, A. K. (2021). Parenting interventions to promote early child development in the first three years of life: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med, 18(5), e1003602. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003602 [ Links ]

Koen, M. (2021). Sustainable future for early childhood: Applying the African ubuntu philosophy to contribute to the holistic development of young children. In W. L. Filho, R. Pretorius, & L. O. de Sousa (Eds.), Sustainable development in Africa: Fostering sustainability in one of the world's most promising continents (pp. 131-146). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74693-3

Laurie, R., Nonoyama-Tarumi, Y., Mckeown, R., Hopkins, C. (2016). Contributions of education for sustainable development (ESD) to quality education: A synthesis of research. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 10, 226-242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408216661442 [ Links ]

Liu, Y., Sulaimani, M. F., & Henning, J. E. (2020). The significance of parental involvement in the development in infancy. Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 10(1), 161-166. https://doi.org/10.5590/JERAP.2020.10.1.11 [ Links ]

Llamas, A. V., & Tuazon, A. P. (2016). School practices in parental involvement, its expected results and barriers in public secondary schools. International Journal of Educational Science, 6(1), 69-78. https://www.academia.edu/23703434/SCHOOL_PRACTICES_IN_PARENTAL_INVOLVEMENT_ITS_EXPECTED_RESULTS_and_BARRIERS_IN_PUBLIC_SECONDARY_SCHOOLS [ Links ]

Lunga, P., Esterhuizen, S., & Koen, M., (2022). Play-based pedagogy: An approach to advance young children's holistic development. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 12(1), a1133. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v12i1.1133 [ Links ]

Mahlomaholo, S., Daries, G., & Koen, M. P. (2022). Creating sustainable early childhood learning environments: A transformatory posthumanist perspective. Educational Research for Social Change. http://ersc.nmmu.ac.za/articles/ERSC_Ed 23-Call_for_Papers_Final_(09-02-22).pdf

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. Jossey-Bass.

Moss, P. (2016). Introduction. In K. Murris (Ed.), The posthuman child: Educational transformation through philosophy and picturebooks. Routledge.

Nathans, L., Brown, A. Harris, M., & Jacobson, A. (2020). Preservice practitioner learning about parent involvement at four universities. Educational Studies,48(4), 529-548. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2020.1793297 [ Links ]

Ntekane, A. (2018). Parental involvement in education. ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.36330.21440

Republic of South Africa. (n.d.). What is early childhood development? https://www.gov.za/faq/education/what-early-childhood-development

Ruto-Korir, R., Jepkemboi, G., & Boit, R. (2020). Sustainability of early childhood education in Kenya: Where are we at the beginning of sustainable development goals? Kenya Studies Review, 8(1), 4255. https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=rWAPqfoAAAAJ&citation_for_view=rWAPqfoAAAAJ:roLk4NBRz8UC

Santana, L., Feliciano, L., Jimenez, A. (2016). Perceived family support and the life design of immigrant pupils in secondary education. Revista de Educción, 372, 32-58. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301890231 [ Links ]

Segoe, B. A., & Bisschoff, T. (2019). Parental involvement as part of curriculum reform in South African schools: Does it contribute to quality education? Africa Education Review, 16(6), 165-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2018.1464692 [ Links ]

United Nations Development Programme. (2015). Sustainable developmental goals. https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. (2014). Teaching and learning: Achieving quality for all. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002256/225660e.pdf

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. (2016). Education for people and planet: Creating sustainable futures for all. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002457/245752e.pdf

Vaughn, L. M., & Jacquez, F. (2020). Participatory research methods: Choice points in the research process. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 1(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.35844/001c.13244 [ Links ]

Wang, V. X., Torrisi-Steele, G., & Hansman, C. A. (2019). Critical theory and transformative learning: Some insights. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 25(2), 234-251. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477971419850837 [ Links ]

Warwick, P., Warwick, A., & Nash, K. (2018). Towards a pedagogy of hope: Sustainability education in the early years. In V. Huggins & D. Evans (Eds.), Early childhood education and care for sustainability: International perspectives (pp. 13-28). Routledge.

Wood, L. (2020). Participatory action learning and action research: Theory, practice and process. Routledge.

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2019). Integrating action learning with action research (ALAR). In O. Zuber-Skerritt, & L. Wood (Eds.), Action learning and action research: Genres and approaches (pp. 69-82). Emerald Publishing.

1 Ethical clearance number: NWU-01232-20-A2

2 Practitioners work with pre-school children in South Africa and hold an NQF Level 4 certificate in ECD, an NQF Level 5 diploma in ECD, or an NQF Level 6 Advanced Certificate in Education; foundation phase and ECD teachers or educators obtain at least an NQF Level 7, Bachelor of Education in Early Childhood Care and Education Degree (Department of Higher Education and Training, 2017).