Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Educational Research for Social Change

versión On-line ISSN 2221-4070

Educ. res. soc. change vol.11 no.2 Port Elizabeth oct. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2021/v11i2a4

Creating an Epistemically Diverse Undergraduate Linguistics Curriculum1

Tracy Nicole BowlesI; Mark de VosII

IDepartment of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, Rhodes University t.bowles@ru.ac.za ORCID No: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9897-3630

IIDepartment of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, Rhodes University m.devos@ru.ac.za ORCID No: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4274-1697

ABSTRACT

This article outlines the implementation of a service-learning course, Linguistics and Community, in a linguistics combined, second- and third-year curriculum. Adopting a qualitative, textual-analytic methodology using Luckett (2001) as an analytical lens, supplemented by quantitative data, we set out to enlist service-learning as one useful means to attain an epistemically diverse linguistics curriculum with reciprocal benefits for both students and community partners. Using a purposive sample, we triangulated data from two data sources: students' reflective journals and an online questionnaire. Our findings showed that the Linguistics and Community service-learning course allowed students to engage in experiential learning, cross-cultural experiences, and become involved with issues related to community building. In doing so, the course exposed students to the relevance of linguistics in everyday life. We argue that a thoughtfully constructed disciplinary-based service-learning programme can be a useful tool in fostering epistemic diversity within a specific discipline such as linguistics and contribute towards the decolonisation of the discipline.

Keywords: service-learning, epistemic diversity, linguistics, reciprocity, literacy, curriculum development

Introduction

Service-learning is a credit-bearing, pedagogical methodology that draws on community engagement to enhance disciplinary learning and civic values of students and allows for a broader appreciation of the discipline by integrating real-life learning within an academic curriculum (Bringle & Hatcher, 1995; Billig, 2011). This is achieved by providing students with opportunities to engage in an organised service activity aimed at addressing genuine community challenges, and a systematic reflection on the experiences gained from the service by applying course content to develop analysis and understanding (Bringle & Hatcher, 1995; Chambers & Lavery, 2012). Service-learning strikes a balance between service and learning, with complementary and reciprocal roles for the learning goals and the service goals. Service-learning allows for flexible "movement between everyday discourses of the community into the more elevated discourses of the university" (Hlengwa 2013, p. 7), and allows for connections to be made between theory covered in class and practical experiences from interactions with the community.

This article establishes the following:

• first, the implementation of a service-learning course in linguistics at Rhodes University in Makhanda (formerly, before 2018, known as Grahamstown) and

• second, the research methods and results deriving from it.

Specifically, we explore how the service-learning course provides a useful means to attain an epistemically diverse linguistics curriculum, using Luckett (2001) as an analytical lens, supplemented by quantitative data and a qualitative, textual-analytic methodology. In designing the course, we drew on the work of Luckett (2001) with the aim of constructing an epistemically diverse curriculum that reciprocally benefits both school learners as well as university students. In this article, we adopt a broad view of curriculum that includes disciplinary content (i.e., syllabus) as well as pedagogy and assessment (Quinn & Voster, 2016); curriculum is the totality of structured learning experiences (Southern African Linguistics and Applied Linguistics Society, 2016).

This article is structured as follows. First, we explain the structure of the service-learning course, and what was done. The next section discusses some of the theoretical underpinnings of the course and the role of service-learning in South African higher education. The following section describes the method of research on the service-learning course. The final section is empirical in nature and presents the results of the research and shows how the Linguistics and Community service-learning is a useful means to attain an epistemically diverse linguistics curriculum.

Structure and Design of the Linguistics Service-Learning Course

The Makana municipality has just over 82,000 inhabitants (Municipalities of South Africa, n.d.), 72% of whom speak isiXhosa, 14% Afrikaans, and 11% English. Situated in South Africa's poorest province, the Eastern Cape, Makana's statistics reflect a poor rural town with high unemployment and few prospects for its youth (see Table 1).

Within this context, the linguistics service-learning course, Linguistics and Community, is an ongoing project of the Department of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies at Rhodes University. The Linguistics and Community course was taught over seven weeks to a combined class of approximately 70 second- and third-year students.2 It has two broad components: on one hand, the classroom activities refer to paired reading conducted at the school service-learning site for the benefit of learners; on the other hand, there are also university-level activities in the university classroom for the benefit of the students.

Nominally described as "the science of language" in introductory texts, linguistics can more appropriately be considered as a set of interrelated language disciplines each with their own objects of study, methodologies, communities of practice, and theoretical desiderata that can be distinguished along various axes. One broad distinction exists between functional and context-oriented objects of study (i.e., what language is used for) versus formal objects of study (i.e., how language is fundamentally constituted). The former covers disciplines such as discourse analysis, applied linguistics, pragmatics, and so forth. These tend to use contextual methodologies with a focus on naturalistic data from social settings. The latter covers disciplines such as phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and so forth. These tend to use abstracted and decontextualised data using empiricist/experimental, one-on-one interview and introspective elicitation techniques.

The fact that linguistics is diverse in this way sets up difficult tensions in constructing a service- learning course that caters to the discipline(s) as a whole: the epistemological values of at least some of the disciplines (abstract, disembodied, objective; Luckett, 2010) may be far removed from the experienced needs of communities (concrete, embodied, subjective, contextual; Luckett, 2010). For example, if a class of linguistics students are paired with Grade 5 learners at a local school with the aim of mentoring their literacy and language proficiency, it is immediately apparent that this fulfils a clear need in a community (addressing literacy); however, it is not immediately clear how such an experience would necessarily lead to a better understanding of language syntax or morphology. Unless these tensions could be resolved, it was not immediately obvious how to facilitate a community-embedded experience that fulfilled the second fork of service-learning, namely, a reciprocal benefit to students in the form of enhanced disciplinary knowledge. Without contributing disciplinary knowledge, a so-called service-learning experience runs the risk of not fulfilling the condition of mutuality and so reduces to voluntarism.

Activities at the University

What sets this service-learning course apart from volunteerism is the fact that it was specifically not aimed at merely (re)teaching practical skills to learners in a community setting. Rather, the emphasis in on mutuality of learning: reflexively and cyclically drawing on the service-learning context to generate insights and understandings that have disciplinary (linguistic) relevance, for example, as a venue for application of existing theory, and/or developing self-awareness of lacunae in students' own knowledge, questioning preconceptions about the "proper" objects of linguistic study, and troubling the established university curriculum itself.

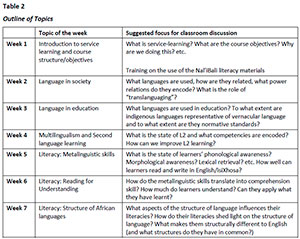

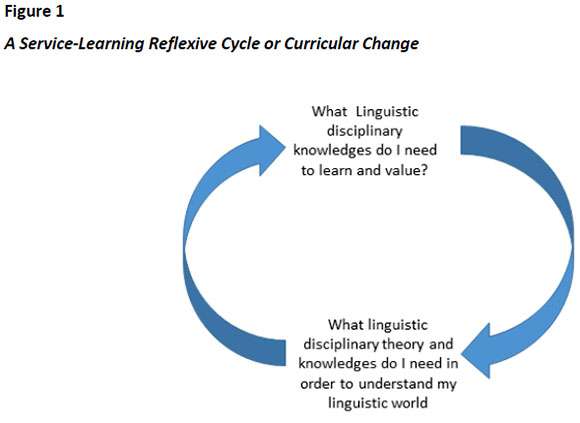

Accordingly, traditional lecture slots were used in decidedly nontraditional ways. Instead of using them to impart new knowledge, they were aimed at consolidating students' understanding of different linguistic approaches covered by the rest of the curriculum, for example, sociolinguistics, language contact, syntax, and literacy studies (see Table 2 for an outline of topics covered), and encouraging them to reflect on the multiplicity of linguistic dimensions of their experience focusing on description, explanation, and practical action. In particular, throughout the course, students were asked to reflect on the following question: "What linguistic theory do I need in order to better understand the linguistic world of the service-learning context?"

We hoped that this would also drive a reflexivity cycle whereby students were prompted to apply disciplinary theory in context and, in turn, see renewed value in theory (Figure 1).3

In keeping with the goal of mutual reciprocity of service-learning, this model sets up the possibility of an epistemic feedback loop whereby we, as academics, gain insight both into communities' needs as well as the theory that is most relevant to those needs-and are thus able to adjust future curricula. In this way, over time, the walls of the ivory tower of academia could become more permeable and responsive to the needs of our communities. The service-learning component thus provides a grounded reflexive cycle upon which to proceed with curriculum transformation. In this way, we hope to use service-learning as a means of decolonising the curriculum and building a renewed disciplinary curriculum fit for purpose in our local context.

Students were asked to draw on, analyse, and discuss their experiences in terms of the course content and readings provided. Formative assessment included weekly reading responses and reflective journal entries. Students were required to write about their service experience in relation to assigned course readings. To assist them, students were guided through a set of questions in the form of a guided reading worksheet (Brown et al., 2016), as detailed in the next section of this article.4 This activity was valuable in linking linguistic issues discussed in the course readings to the service-learning context. Guided readings are an example of an active learning teaching technique (Brown et al., 2016), used to motivate student effort and enhance learning. "The primary goal of active learning techniques is to shift away from surface learning toward deep learning, such that students develop their understanding through more active and constructive processes" (Ritchhart et al., 2011, cited in Brown et al., 2016, p. 258).

Students are directed through the prescribed readings via a dialogue-like structure, in which the lecturer provides a summary of key sections in the readings and then asks the student questions about this content and how they can make sense of it in relation to their experiences in the community setting. Table 2 above gives an indication as to the types of issues addressed in the guided reading worksheets. Through their reflective journals, students brought the course materials, readings, and their experiences through service together in narratives, thereby providing an opportunity to reflect on and analyse their thoughts, experiences, beliefs, and assumptions.

At the end of the course, students wrote a short story in the style of the Nal'ibali (https://nalibali.org) series of bilingual (isiXhosa-English) literacy supplements that was custom-made for their learners' linguistic needs (e.g., incorporating learners' literacy levels, names, interests, language, contexts, etc.). As part of the summative assessment for the course, students then wrote an essay in which they reflected on the linguistic-disciplinary choices (e.g., word choice, use of code-switching, word length, sentence structure, etc.) they made in writing their story.

Activities During the On-Site Service Learning Visits

Students visited a local under-resourced Quintile 3 school twice a week for 45 minutes each. Each student was paired with a Grade 5 learner with the aim of mentoring learners' reading literacy using the Nal'ibali literacy supplements to guide their interactions. The interactions involved paired reading between learners and students in both isiXhosa, which is the home language of the learners, and English, the learners' first additional language and medium of instruction. The benefits for the learners are that they obtain mentoring in literacy practices by more experienced readers who are sensitive to the nuances of language in the sense that they study linguistics and that ultimately, their literacy skills improve. It is important to add that the students do not attempt to teach the learners.

Theoretical Overview

In this literature overview, we first outline our analytical lens, namely Luckett's (2001) model for an epistemologically diverse curriculum, before providing an overview of the role of service-learning in the South African higher education context. Thereafter, we explore some of the theoretical issues informing our choices in the design and development of our own service-learning course.

Luckett's Epistemologically Diverse Curriculum

Luckett (2001) proposed four ways of knowing that contribute to students' development of different kinds of competencies, which she argues should be present in any higher education context. These competencies are represented along two axes: practice/theory and subjective/objective (alternatively called contextual/decontextual), with each resulting quadrant representing a particular kind of knowledge and its associated competencies. The competencies are foundational (knowing that), practical (knowing how), personal (knowing from personal experience), and reflexive (knowing how you know). Luckett (2001) suggested that the relative emphasis and combinations of each of the four ways of knowing would be different for different disciplines, qualifications, and contexts of implementation. Luckett's model is represented in Figure 2 below.

The first quadrant deals with propositional knowledge: the knowing of specific disciplinary knowledge, traditional first-level cognitive learning (Quinn & Vorster, 2016). This includes everyday learning in lectures, reading in the library, note taking, and so forth. Given that this quadrant places a strong emphasis on propositions and thus on the facts, there is little place for application or practice. Although propositional knowledge remains an important pillar of the higher education curriculum, knowing in higher education needs to be challenged and complemented with other ways of knowing (Cross & Govender, 2021; Gugushe, 2009; Hoadley, 2011).

Quadrant 2, practical knowledge (Luckett, 2001), deals with practical, embodied knowledge. This refers to "knowing how" and involves the application of disciplinary knowledge acquired in the first quadrant (Quinn & Vorster, 2016). The development of practical competency requires learning to take place through apprenticeship and by doing within controlled, delimited, decontextualised environments (Quinn & Vorster, 2016) under the guidance of the teacher in the classroom, in tutorials, or in the laboratory.

The third quadrant deals with experiential knowledge including self-motivation, self-confidence, innovation, creativity, teamwork, social sensitivity, negotiation, leadership, citizenship, and so forth (Luckett, 2001). Quadrant 3 involves the application of learning from both Quadrants 1 and 2. This type of learning takes place away from the safe, constructed contexts of the lecture hall and laboratory and students are given opportunities to gain experiential knowledge in authentic, unpredictable, real-life contexts; to view and analyse their experience through the lenses of the objective/decontextualised knowledges (Quadrants 1 and 2) gained through formal study. It is this process of building experiential knowledge that also potentially catalyses the development of Quadrant 4, namely, reflexive/epistemic knowledges. According to Luckett (2001, p. 56), "experiential learning is one of the best ways to get learners to engage with and commit themselves to their studies and future careers, but also because this entails critical epistemic shifts." Students learn by thinking reflexively and meta-cognitively and thus learn about themselves and their own thinking processes (Quinn & Vorster, 2016). Quadrant 3 learning also allows students to be exposed to others (Luckett, 2001), forcing them to evaluate their own subjectivities and knowledge in the light of other ways of knowing and being in the world.

Finally, Quadrant 4 deals with epistemic knowledge and reflexive competence. This quadrant places emphasis on knowing how you know what you know. Learning involves the development of meta-cognition, which involves thinking epistemically, contextually, and systematically (Luckett, 2001), and requires integration of the first three quadrants. This involves "an awareness of how and why one thinks and learns as one does, and the capacity to recognise and evaluate the assumptions and limits of theories of knowledge and to be able to suggest alternatives" (Luckett, 2001, p. 57). Quadrant 4 can be applied at differing levels of complexity. Initially, it may involve making explicit "disciplinary conceptual frameworks, epistemic rules, methods and conventions of the discipline" (Luckett, 2001, p. 56), however, at advanced levels, students ought to be exposed to more complex and unpredictable contexts and types of problems that encourage thinking beyond the boundaries of a particular discipline and embrace paradigmatic and epistemic plurality; "this requires the ability to stand back from one's own frame of reference and epistemology and also to recognise the validity of other ways of knowing" (Luckett, 2001, p. 57).

An epistemically diverse curriculum (Luckett, 2001) integrates learning from all four quadrants. It thus provides multiple opportunities for students to gain cognitive, epistemic, and physical access to knowledge within their discipline and in their studies. It develops both knowledge and skills that are required for economic productivity, political participation, and responsive citizenship in a diverse democracy. It holds in tension disciplinary knowledge and applied interdisciplinary knowledge, global and local forms of knowledge, as well as equity and development demands faced by the higher education system (Luckett, 2001). This type of curriculum actively speaks to Moll's (2004) four domains of responsiveness of a curriculum, namely, economic, cultural, disciplinary, and learner responsiveness. Accordingly, we set out to enlist service-learning as one useful means through which to attain an epistemically diverse linguistics curriculum.

Service-Learning in South African Higher Education

The theoretical origin of service-learning can be traced back to John Dewey's (1933-1938 as cited in Giles & Eyler, 1994) theory of experience and education-particularly his ideas of democracy, learning from experience, and linking the school to the community. According to Giles and Eyler (1994), the aims of learning from experience, a connected view of learning, social problem-solving, and education for citizenship-some of the cornerstones of service-learning-are all implicit in Dewey's writings. Another of Dewey's key contributions to service-learning is that of reflective practice (Giles & Eyler, 1994). "The role of reflection in learning from experience has been made explicit in Dewey's assertion that 'we do not learn from experience; we learn from reflecting on experience'" (Pacho, 2015, p. 13). This idea of reflective practice has become foundational in service-learning pedagogy and forms the foundation of the Linguistics and Community service-learning course.

Continual demands placed on the transformation of South African higher education attest to the need for a more responsive curriculum in higher education programmes (Fomunyam & Teferra, 2017). For example, calls for the recognition of different sources of knowledge and acknowledgement of diverse styles of learning amongst students (Cross & Govender, 2021; O'Brien, 2005) speak to the need for increased learner responsiveness (Moll, 2004). One of the ways in which higher education institutions have responded to the calls for transformation is through the development of community-based service-learning programmes (Department of Education, 1997), a goal of the National Plan for Higher Education, 2001 and the White Paper of 2013 (as cited in Hlengwa & McKenna, 2017). Thus, according to Hlengwa (2013, p. 3), "service-learning is afforded a privileged position in relation to the transformation of higher education in South Africa." Service-learning provides a platform for focused activities within the community, and is framed as having the potential for enhanced engagement with societal issues (Hlengwa & McKenna, 2017). It is therefore seen as a visible measure of the social responsiveness of higher education to the greater public good (Singh, 2014). "Service-learning can be seen as a means by which to produce graduates who are not only steeped in disciplinary knowledge, but who are also conscious of how that knowledge can be used to alleviate societal pressures" (Hlengwa & McKenna, 2017, p. 132).

Osman and Peterson (2013) situated community-based theory in a South African context and argued for a broad theoretical framework of thinking about service-learning for social change. They argued that the use of a critical social and educational theory of service-learning challenges dominant hegemonic practices within disciplines in higher education (Osman & Peterson, 2013). Thus, students are encouraged to take an active role in their learning and in cultivating an awareness of how society is shaped by political, social, and cultural systems and how these affect their profession or discipline. This builds on the work of Howard (1998), who argued for the disruption and destabilisation of traditional roles, relationships, and norms in favour of re-socialising new classroom behaviours in attempts to create what she called the synergistic classroom. The synergistic classroom encourages social responsibility, active participatory student involvement, academic and experiential learning, all in line with the goals and values underlying a service-learning pedagogy as proposed by Giles and Eyler (1994), Osman, and Peterson (2013).

Osman and Peterson (2013) challenged earlier, deficit approaches to service-learning as charitable and voluntaristic, which they argued, reinforce positions of power and privilege. What distinguishes service-learning from voluntarism and other types of learning is the combination of disciplinary learning, service, and personal growth for the students in a mutual, reciprocal relationship (Butin, 2003; d'Arlach et al., 2009; Rossiter, 2006; Sigmon, 1979). Reciprocity broadly involves mutual benefits of the service-learning interaction between the student and the service-learning partner. This can take many forms, such as obtaining greater facility with disciplinary propositional knowledge (Quadrant 1), putting theory into practice in delimited contexts (Quadrant 2), coming to new personal insights about the discipline and its application in authentic contexts (Quadrant 3), attaining increased awareness of disciplinary epistemologies and how it may relate to other ways of knowing (Quadrant 4).

Service-learning is central to the transformation of student perspectives and practices (Felten & Clayton, 2011) through assisting students in the development of new understandings, which are based on real-life experiences. Such a curriculum can provide students with opportunities in which they are exposed to cross-cultural experiences and in which they can start engaging with issues related to citizenship, identity, and community-building (Luckett, 2001). In doing so, a service-learning course can assist in preparing students to be active and critical civic-minded graduates, which is one of the goals of higher education in South Africa (Paphitis & Kelland, 2016).

Service-learning is also a means of contesting the traditional roles of the lecturer and student (Osman & Peterson, 2013, p. 13), thus invigorating the relationship and encouraging students to see themselves as knowledge producers. The lecturer is no longer the only "expert" in the classroom and both the community partner and students have key roles to play in the learning process as well. The lecturer's role thus changes from being the sole knowledge (re)producer, to the curator of service-learning experiences and facilitator of students' learning. The lecturer should provide guidance for students in making the connection between what they have learned in the classroom to the actions and experiences they gain through the service activity and the consequences of those actions and experiences. The lecturer's role thus shifts from having control over student learning to providing students with platforms to manage and structure their own learning, giving students agency in the classroom. This can prove quite unsettling for some lecturers whose own assumptions, privileges, and prejudices around "what learning is" often become challenged. Thus, service-learning provides a structural change that destabilises cultural understandings of what learning is, on the part of both lecturers and students.

These enabling characteristics of service-learning thus resonate with calls for decolonisation of the curriculum and increased responsiveness of the university to both society and the individual student, and which have placed pressure on universities as institutional bodies to not only change their colonial structures and cultures (Archer, 2005), but also change their curricula. According to Mbembe (2015), the university classroom is a colonial construct that needs to incorporate more nuanced spaces, and place increasing value on student-teacher relationships that allow platforms for the redistribution of different kinds of knowledge. He called this the "classroom without walls" (Mbembe, 2015, p. 5). Service-learning pedagogy is one example of this because it challenges the knowledge promoted in universities by "drawing on local knowledge, cultural understandings, and practices" (Akhurst et al., 2016, p. 137). However, this notion of the classroom without walls can be a somewhat contested concept within the humanities in general and (at least some types of) linguistics in particular. This is because, as pointed out by Seider and Taylor (2011), "most humanities programmes present very few opportunities for students to do 'out of class activities,' as it is assumed that the humanities is a territory of abstraction and reflection, but not one of action" (p. 201). Service-learning thus provides an opportunity to engage in real ways with contested notions of transformation and decolonisation of knowledge. The discipline of linguistics offers great potential for service-learning because there are multiple ways in which language-related theory can be put into context.5

Method of Research

In the previous sections, we outlined the service-learning course and its theoretical underpinnings; in setting up a linguistics service-learning course, we wished to develop an epistemically diverse curriculum with mutual benefits for both learners and students. In this section, we focus on the research about the course.

Having set up a service-learning course we set out to research how the service-learning course reflected in changes in the epistemic personal orientations of students, specifically in terms of Quadrant 3 types of knowledge (experiential knowledge) and Quadrant 4 types of knowledge (epistemic knowledge).

We adopted a qualitative, textual-analytic methodology using Luckett (2001) as an analytical lens, supplemented by quantitative data. We used a purposive sample of participants, consisting of Linguistics 2 and Linguistics 3 students of the Linguistics in Community course. We triangulated data from two data sources: an online questionnaire after the course, and students' reflective journals.

We conducted a post-course online survey of student experiences (N = 22: Linguistics 2, 52%; Linguistics 3, 48%). Although participation in the course was compulsory, participation in the subsequent research was on an opt-in basis. Even though students were not anonymous when submitting, the data were anonymised prior to analysis. No additional personal, biographical, ethnic, or individually defining data were collected because these were not variables in our study. Questions included responses on a Likert-scale as well as qualitative textual responses.

In addition, students were also given the opportunity to reflect on their experiences through a weekly online journal (n = 67 total submissions) prompted by weekly guided readings. To analyse the qualitative data, we used a deductively-driven thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2012; Kiger & Varpio, 2020) based on Luckett's (2001) quadrants for the analysis, namely propositional, practical, experiential, and epistemic knowledges. The qualitative data were evaluated according to whether they expressed a position in relation to Luckett's (2001) categories, for example, through lexical sets, word choice, connotations, denotations, and other general features of the text. The text was then thematically coded according to how the text evoked the types of knowledge and epistemic orientations of the quadrants.

Results and Discussion

This section first presents the results from the quantitative data from the student online questionnaire, and then the qualitative data that demonstrate changes in the epistemic personal orientations of students, specifically in terms of the types of knowledge associated with Quadrant 3 (experiential) and Quadrant 4 (epistemic).

Evidence of Change for Learners

In analysing the online student questionnaire, respondents were asked to rate statements on a 5-point scale ("strongly disagree," "mostly disagree," "neither agree nor disagree," "mostly agree," "strongly agree") coded according to their perception of whether their learner's reading skills or attitude to reading had improved, as well as whether there was an overall positive influence on the learner (Table 3). Results were summarised and neutral responses ("neither agree nor disagree") were excluded. Forty-one per cent of respondents felt that their learners' reading had improved over the course of the mentorship programme and only 23% felt that their learners' reading had not improved (M = 3, SD = 1.29). There were also improvements in attitude to reading (55% vs. 27%; M = 4, SD = 1.51) and the perception that mentorship had had a positive influence overall (56% vs. 19%; M = 4, SD = 1.29).

Table 3 shows that students generally perceived learners to have experienced some improvement in their reading literacy, attitudes toward reading, and positive experience of mentorship in general. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that the experience of the school and its learners was very positive; we had several teachers as well as the principal expressing their appreciation, mentioning the positive difference the programme had made to the learners.6

Evidence of Change in Students' Outcomes

The main focus of this article is on how the service-learning course was experienced by our university students. Using the online student questionnaire, the data pertaining to student outcomes were treated in the same way as above. Stimulus statements were coded on a 5-point Likert scale and results were totalled while excluding neutral responses. In addition, the stimulus statements were coded according to Luckett's axes of knowledge (Table 4). Forty-six per cent (vs. 10%; M = 3, SD = 0.96) of respondents indicated that the service-learning course assisted them in being able to connect theory and practice, and 56% (vs. 14%; M = 4, SD = 1.1) agreed that the course aided them in being able to develop ideas and support them with appropriate arguments. Sixty-three per cent (vs. 10%; M = 4, SD = 1.0) indicated improved ability to critically reflect on and address real-life problems; 64% (vs. 14%; M = 4, SD = 1.9) indicated improved ability to take decisions and act ethically and professionally; 72% (vs. 14%; M = 4, SD = 1.25) reported improved ability to take responsibility and to reflect on how the impact of their choices might affect others.7

The ability to develop ideas and support them with linguistically informed arguments reflects propositional knowledges (Quadrant 1). Table 4 shows that 56% of students agreed that the course supported this quadrant. The remainder of the stimuli attempt to explore Quadrant 3, which is characterised by higher levels of contextual and practice-led learning. Quadrant 3 requires students to apply their knowledge within the uncertain and unpredictable contexts that characterise the real world. It is within Quadrant 3 that learning proceeds through "engaging personally and thinking reflexively" (Luckett, 2001, p. 55). Table 4 shows that 46% of students agreed that the service learning course supported the opportunity to connect theory and practice.

The next two stimuli in Table 4 ("Take decisions and act ethically and professionally" and "Take responsibility and reflect on the impact this may have on others") also require Quadrant 3 knowledges embedded in context and reflexive practice. They are also relevant to Quadrant 4, which Luckett (2001) suggested "could allow students to rethink their assumptions about values, ethics and social responsibility" (Luckett, 2001, p. 57). Orientation within these quadrants of knowledge requires a sincere, authentic, and empathetic (Rossiter, 2006) acknowledgement of the other-that one's decisions have an impact on others and that others may see and experience the world differently to oneself. Thus, they inherently point to epistemic shifts and an awareness of one's subjectivity. Sixty-four per cent of students agreed that the service-learning course supported their ability to take decisions and act ethically and professionally, and 72% indicated that the course enabled their ability to take responsibility and reflect on the impact this may have on others (Table 4). The majority of change was experienced in Quadrants 3 and 4, which is where the strengths of service-learning are most significant (Akhurst et al. 2016; Hlengwa & Mckenna, 2017; Luckett, 2001; etc.). The quantitative data thus lend credence to the notion of a service-learning course as developing different knowledge types as part of an epistemically diverse curriculum.

An Epistemically Diverse Curriculum: Student Reflections

A premise of our approach was that students had already been exposed to the relevant theory in other linguistics courses. The service-learning course thus differs from traditional linguistics courses in that it is not an avenue for the teaching of additional theory (Quadrant 1, propositional knowledges). Rather, it seeks to allow students to experience a real-life setting and then evaluate how disciplinary theory can be used to better understand it. This epistemic question is encapsulated in what is frequently posed to students, 'What linguistic theory is required to help you engage with your service-learning experiences?'

In this way, the course emphasises application of theory both in Quadrants 2 and 3. For Quadrant 2, students are required to start to think meta-cognitively and are afforded the opportunity to make connections between theory and application in safe spaces such as the classroom, reflective journal entries, and guided reflective exercises. The real strength of the course, however, lies in Quadrant 3. Quadrant 3 takes the students out of the classroom and involves experiential knowledge in the context of the real-world, emphasising learning from experience, reflective practice (Giles & Eyler, 1994), and service-learning for social change (Osman & Peterson, 2013), in which students take on an active role in their learning. Students are encouraged to start engaging personally and thinking reflexively about what they are doing (Luckett, 2001) and how this relates to linguistic theory. The following student quotes show that the course was instrumental in making classroom theory more real and demonstrating its applicability:

We got to see what we were learning via theory and what was occurring in everyday situations.

I think it provided me with more information about issues I knew existed but didn't know the intricate details of, for example.

It embeds you in the context you have been evaluating and studying from afar. It allows you to see the effects.

[The service-learning course] gave us a firm grounding in the area of language and linguistics in a South African context, and also clearly illustrated how this knowledge can be applied to everyday issues (e.g. the literacy crisis) and help solve them.

It [the service-learning course] really highlighted how linguistics Is constantly around us and impacts daily life. It also showed how a knowledge of linguistics can be used and applied to issues.

It is within this Quadrant 3 that students become more agentive, starting to take control of their own learning. The following student quotations indicate incipient agency, mostly indicated through a willingness instantiate critical citizenship by improving the lives of others; interestingly, this may also indicate the early stages of Quadrant 4 because as Luckett (2001) put it: "It is in this quadrant [4] or moment of the curriculum that [students] could develop the capacity for transferring generic skills" (p. 57):

Having come from a public school myself, I had to use the resources available to me to help someone who was going through what I had gone through.

This module has helped me to think of ways to improve learners' reading abilities and confidence through establishing a relationship with the learner.

It has made me think of linguistics as making meaningful and relevant contributions to sectors of society in order to improve the quality of life experienced by people.

I used to think that linguistics was too advanced [however the course] has made me realise that linguistics is extremely beneficial in my degree, as it helps me to understand how to help the learners learn to read and how to improve their reading skills.

Knowledge of linguistics can be used and applied to issues, and help solve them.

We can improve literacy and education by only investing some time and effort.

I am more willing to share and plough back into the community.

There is also some evidence of students taking positions in relation to the discipline and the service-learning experience. Admittedly, these are still situated at a fairly emotional level (as opposed to a critical and nuanced stance on a theoretical position, for example), but these student quotes nevertheless give an indication of them beginning to develop a contextual subjectivity in relation to the discipline:

It has just reaffirmed my belief that having a good understanding of linguistics is necessary in a classroom context.

Mostly, I didn't have a sense of how bad the problem was. Now that I do it just frustrates me that linguistic knowledge about literacy isn't receiving enough credence in decision making around education in South Africa.

What excites me is seeing the linguistics theory that I have learnt thus far playing out in real-life situations. (Reflective journal entry)

Deeper personal engagement and honest reflection can also be uncomfortable and lead to concerns and fears. Facing these is an agentive act and can lead to personal insights. This is demonstrated in the students' reflective journal entries included below (our emphases):

I feel trepidation at the prospect of having to teach young learners the act of reading.

Another fear I had was that neither the learners nor myself would be able to understand too much of each other because of our language barrier. However, it turned out that my understanding of some words of Xhosa and the children's knowledge of English was sufficient enough to elicit more than basic communication.

It [the reading] was definitely not a waste of time, there were some really interesting points that forced me to re-examine my own ways of thinking and some of that was really uncomfortable.

I am humbled by the fact that I do not know everything and that there is a lot to learn from the learner that I will be assigned to... . It is also encouraging because I get to witness an immediate effect of the theory that I have learnt.

I have placed myself in uncomfortable place by mentoring and tutoring learners.

Quadrant 4 involves the development of reflexive, epistemic knowledge (Luckett, 2001) where students are encouraged to start thinking meta-cognitively and epistemically. In their assignments, students are encouraged and required to engage critically and demonstrate reflexivity as well as demonstrate propositional, practical, and experiential knowledge. Students' reflexivity is demonstrated in their responses to the course evaluation, as included below:

I have grasped the concept over this past week that in order to engage with issues more fully and interact with my learner on a deeper level, I would have to be equipped with linguistic theory and tools. (Reflective journal entry)

This course has helped me in thinking critically about linguistics within the South African context in relation to the importance of code switching and familiarising learners with their home languages within the classroom.

It has provided me with a more critical and contextual outlook on linguistics, rather than limiting me to just learning from readings.

An epistemically diverse curriculum provides a platform in which students can come to understand that knowledge is socially constructed, historically and culturally specific, and that their personal judgments are contextually contingent (Luckett, 2001). This involves a personal transformation on the part of the student and often involves some form of cognitive dissonance through exposure to different experiences and perspectives (Luckett, 2001). According to Luckett (2001), one of the ways in which this can be achieved is through a service-learning course because this provides the ideal contexts for the development and integration of personal, social and leadership skills and develops the students' capacity in achieving critical cross-field outcomes.

In particular, a service-learning course promotes greater social responsibility amongst students to help them become better citizens (Felten & Clayton, 2011). For many students, the ways in which the majority of South Africans live their lives are mediated through media, common-sense tropes, and prejudices. It is therefore important that our students, if they are to be the leaders of tomorrow, have direct engagement with real people in real contexts. Through the service-learning course, students are placed in positions of responsibility (i.e., mentoring) which allows them to exercise leadership, responsibility, punctuality, professionalism and other important values and gives them greater agency over their learning. The service-learning course therefore enhances students' understanding of linguistics through the lens of service, and thus promotes the development of critical, civic-minded students, and pushes students to become more engaged citizens. These skills reflect the critical cross-field outcomes that are outlined in the National Qualifications Framework (SAQA, n.d.).

An epistemically diverse curriculum is one that integrates learning from all four quadrants (Luckett, 2001):

The Integration of learning in quadrants one and two with the ways of knowing in quadrants three and four is crucial, not only because experiential learning is one of the best ways to get learners to engage with and commit themselves to their studies and future careers, but also because it entails critical epistemic shifts. (p. 32)

It thus provides multiple opportunities for students to gain cognitive, epistemic, and physical access to knowledge within their discipline and in their studies.

An epistemically diverse curriculum is thus characteristic of the synergistic classroom (Howard, 1998). The Linguistics and Community service-learning course integrates all four quadrants simultaneously with differing levels of engagement and reflexivity throughout the course. It is therefore illustrative of an epistemically diverse curriculum (Luckett, 2001). This service-learning course allowed students to engage in experiential learning, cross-cultural experiences, and with issues related to community building (Fitzgerald, 2010; Luckett, 2001). In doing so, it exposed students to the relevance of linguistics in everyday life (Fitzgerald, 2010). The course therefore can be seen to have contributed towards preparing students to participate productively as critical and civic-minded graduates, which corresponds to one of the goals of the university (Luckett, 2001; Paphitis & Kelland, 2016). This is illustrated in the student quotations below:

It has made me think of linguistics as making meaningful and relevant contributions to sectors of society in order to improve the quality of life experienced by people.

Linguistics has become more anthro-centric and relevant to the human condition.

Conclusion

Our findings showed that the Linguistics and Community service-learning course allowed students to engage in experiential learning, cross-cultural experiences, and become involved with issues related to community building. In doing so, the course exposed students to the relevance of linguistics in everyday life. By drawing on Luckett (2001), we have argued for the utility of including service-learning, designed with the discipline in mind, the linguistics curriculum in order to achieve an epistemically diverse curriculum that is mutually beneficial to students and community partners. This meets both institutional goals and social reform imperatives but, just as importantly, as we have attempted to show in this article, it contributes toward linguistic disciplinary goals such as applying theory to practice, situating theory in real contexts, and contributing within toward the decolonisation of the discipline.

References

Akhurst, J., Solomon, V., Mitchell, C., & van der Riet, M. (2016). Embedding community-based service learning into psychology degrees at UKZN South Africa. Educational Research for Social Change, 5(2), 136-152. http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/ersc/v5n2/10.pdf [ Links ]

Archer, M. (2005). Structure, culture and agency. In M. D. Jacobs & N. W. Hanrahan (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to the sociology of culture (pp. 17-34). Blackwell.

Billig, S. H. (2011). Making the most of your time: Implementing the K-12 service-learning standards for quality practice. The Prevention Researcher, 18(1), 8-14. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ914156 [ Links ]

Bowles, T. N. (2019). A critically reflective account of the psycholinguistics undergraduate strand [Unpublished postgraduate diploma portfolio]. Rhodes University. [ Links ]

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 57-71). American Psychological Association.

Bringle, R. G., & Hatcher, J. A. (1995). A service-learning curriculum for faculty. Michigan Journal of Service-Learning, 2, 112-122. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ552434 [ Links ]

Brown, C. A., Danvers, K., & Doran, D. T. (2016). Student perceptions on using guided reading questions to motivate student reading in the flipped classroom. Accounting Education, 25(3), 256-271. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2016.1165124 [ Links ]

Butin, D. W. (2003). Of what use is it? Multiple conceptualizations of service-learning in education. Teachers College Record, 105(9), 1674-1692. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1065160 [ Links ]

Chambers, D. J., & Lavery, S. (2012). Service-learning: A valuable component of pre-service teacher education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(4), 128-137. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2012v37n4.2 [ Links ]

Cross, M., & Govender, L. (2021). Researching higher education in Africa as a process of meaning-making: Epistemological and theoretical considerations. Journal of Education 83, 14-33. https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i83a01 [ Links ]

d'Arlach L., Sánchez, B., & Feuer, R. (2009). Voices from the community: A case for reciprocity in service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 5-16. https://www.academia.edu/77157870/Voices_from_the_Community_A_Case_for_Reciprocity_in_Service_Learning [ Links ]

Department of Education. (1997). Education White Paper 3: A programme for the transformation of higher education.https://www.gov.za/documents/programme-transformation-higher-education-education-white-paper-3-0

Felten, P., & Clayton, P. (2011) Service learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 128, 7584. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.470 [ Links ]

Fitzgerald, C. M. (2010). Developing a service-learning curriculum for linguistics. Language and Linguistics Compass 4(4), 204-218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818x.2010.00196.x [ Links ]

Fomunyam, K. G., & Teferra, D. (2017). Curriculum responsiveness within the context of decolonisation in South African higher education. Perspectives in Education, 35(2), 196-207. http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v35i2.15 [ Links ]

Giles, D. E., & Eyler, J. (1994). The theoretical roots of service-learning in John Dewey: Toward a theory of service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 1, 77-85. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/slceslgen/150/ [ Links ]

Gugushe, T. (2009). The four ways of knowing in dental education: An epistemological perspective. SADJ: Journal of the South African Dental Association, 64(5), 219. https://purerims.smu.ac.za/en/publications/the-four-ways-of-knowing-in-dental-education-an-epistemological-p [ Links ]

Hlengwa, A. (2013). An exploration of conditions enabling and constraining the infusion of service-learning into the curriculum at a South African research-led university [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Rhodes University. [ Links ]

Hlengwa, A., & McKenna, S. (2017). Dangers of generic pedagogical panaceas: Implementing service-learning differently in diverse disciplines. Journal of Education, 67, 129-148. https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i67a06 [ Links ]

Hoadley, U. (2011). Knowledge, knowers and knowing: Curriculum reform in South Africa. In L. Yates & M. Grumet (Eds.), Curriculum in today's world: Configuring knowledge, identities, work and politics (pp. 143-158). Routledge.

Howard, J. P. F. (1998). Academic service learning: A counter normative pedagogy. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 73, 21-29. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ561316 [ Links ]

Howie, S., Combrinck, C., Roux, K., Tshele, M., Mokoena, G., & McLeod Palane, N. (2017). PIRLS 2016 Grade 5 benchmarking participation: South African children's reading literacy achievement. University of Pretoria. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.14466.17601

Howie, S., van Staden, S., Tshele, M., Dowse, C., & Zimmerman, L. (2012). PIRLS 2011 summary report: South African children's reading literacy achievement. University of Pretoria.

Howie, S., Venter, E., van Staden, S., Zimmerman, L., Long, C., du Toit, C., Scherman, V., Archer, E et al. (2008). PIRLS 2006 Summary report: South African children's reading literacy achievement. University of Pretoria.

Kiger, M. E., & Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Medical Teacher, 42(8), 846-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2020.1755030 [ Links ]

Luckett, K. (2001). Responding to equity and development imperatives: Conceptualising a structurally and epistemically diverse curriculum in post-apartheid South Africa. Equity & Excellence in Education 34(3), 26-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/1066568010340304 [ Links ]

Luckett, K. (2010). Knowledge claims and code of legitimation: Implications for curriculum recontextualisation in South African higher education. Africanus, 40(1), 6-20. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. (2015). "Decolonizing knowledge and the question of the archive": Africa is a country. Platform for Experimental, Collaborative Ethnography. https://worldpece.org/content/mbembe-achille-2015-%E2%80%9Cdecolonizing-knowledge-and-question-archive%E2%80%9D-africa-country

Moll, I. (2004). Curriculum responsiveness: The anatomy of a concept. In H. Griesel (Ed.), Curriculum responsiveness: Case studies in higher education (pp. 1-17). South African Universities Vice-Chancellor Association.

Municipalities of South Africa. (n.d.). Makana local municipality. https://municipalities.co.za/demographic/1017/makana-local-municipality

O'Brien, F. (2005). Grounding service learning in South Africa. Acta Academica Supplementum, 3, 6498. https://scholar.ufs.ac.za/xmlui/handle/11660/9803 [ Links ]

Osman, R., & Petersen, N. (2013). An introduction to service learning in South Africa. In N. Petersen & R. Osman (Eds.), Service learning in South Africa (pp. 2-32). Oxford University Press.

Pacho, T. O. (2015). Unpacking John Dewey's connection to service-learning, Journal of Education & Social Policy, 2(3), 8-16. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285200637_Unpacking_John_Dewey's_Connection_to_Service-Learning [ Links ]

Paphitis, S., & Kelland, L. (2016). The university as a site for transformation: Developing civic-minded graduates at South African institutions through an epistemic shift in institutional culture. University of Johannesburg and UNISA Press, 20(2), 184-203. https://doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/906 [ Links ]

Quinn, L., & Vorster, J. (2016). Conceptualising an epistemically diverse curriculum for a course for academic developers. South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(6), 24-38. https://doi.org/10.20853/30-6-717 [ Links ]

Rossiter, M. (2006). Radical mutuality and self-other relationship in adult education. In S. Merriam, B. Courtenay, & R. Cervero (Eds.), Global issues in adult education: Perspectives from Latin America, Southern Africa and the United States (pp. 387-398). Jossey-Bass.

Southern African Linguistics and Applied Linguistics Society. (2016). Resolutions of the first Transformation in Linguistics Summit 2016.https://salals.org.za/2019/03/25/resolutions-of-the-first-transformation-in-linguistics-summit-2016/

South African Qualifications Authority (n.d.). Registered qualification: Bachelor of Arts, Qualification ID 23375. https://regqs.saqa.org.za/viewQualification.php?id=23375

Seider, S., & Taylor, J. (2011). Broadening college student interest in philosophical education through community service learning. Teaching Philosophy, 34(3), 197-217. https://doi.org/10.5840/teachphil201134330 [ Links ]

Sigmon, R. L. (1979). Service-learning: Three principles. Synergist, (Spring), 9-11. https://nsee.memberclicks.net/assets/docs/KnowledgeCenter/IntegratingExpEduc/BooksReports/ 55.%20service%20learning%20three%20principles.pdf

Singh, M. (2014). Higher education and the public good: Precarious potential? ACTA Academica, 46(1), 98-118. http://www.ufs.ac.za/ActaAcademica [ Links ]

1 This article is adapted from a chapter in Tracy Bowles' Postgraduate Diploma in Higher Education portfolio, which was submitted to Rhodes University on 3 December 2019 (Bowles, 2019). The authors conceptualised, developed, and taught the service-learning course together. Both authors contributed substantially to the final text of this article.

Ethical clearance number: 96105 School of Languages & Linguistics Joint Research Ethics Committee of Rhodes University.

2 This modular configuration was an artefact of other general factors in the department, and is not a design feature of the Linguistics and Community course.

3 See also Quinn & Vorster (2016, p. 11), who asked a similar question with respect to academic development: "What do the theories and concepts mean to me in the context of my work as an academic developer in my specific institution?"

4 Note that "guided reading" is a technical term referring to a particular way of scaffolding reading of academic texts for the students (Brown et al., 2016). It ought not to be confused with "paired reading," which refers to the approach adopted to classroom reading in the service activity.

5 This especially applies in the areas of language learning and literacy (Fitzgerald, 2010), which is of ongoing national social and economic importance (see Howie et al., 2008, 2012, 2017). It must be stressed, however, that these relate to very specific subdisciplines of applied linguistics. One must therefore avoid the temptation to see these areas as "natural" or sufficient extensions of a linguistics curriculum per se. The disciplines of linguistics encompass a much richer diversity of possible service-learning experiences, as we demonstrate in this article.

6 We thank the reviewer for pointing out a possible limitation. A limitation of this research is that we were not able to test learners' improvements directly because we did not have ethical clearance to do so and it fell outside the scope of a service-learning community engagement project of this nature.

7 These questionnaire stimuli were drawn from the outcomes in the course outline, which in turn, were drawn from the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA, n.d.) Bachelor of Arts level descriptors. They were also chosen because they resonate with the epistemic orientations described by Luckett (2001).