Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Educational Research for Social Change

versión On-line ISSN 2221-4070

Educ. res. soc. change vol.10 no.2 Port Elizabeth sep. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2021/v10i2a5

ARTICLES

A Visual Conversation From South Africa: Climate Resilience and Hope for a Green Recovery

Kim BermanI; Janis SarraII

IUniversity of Johannesburg kimb@uj.ac.za ORCID No: 0000-0003-1537-9714

IIUniversity of British Columbia sarra@allard.ubc.ca ORCID No: 0000-0002-2725-7661

ABSTRACT

As the world copes with two parallel catastrophic events-climate change and COVID-19, this article examines how visual art students in South Africa used the pandemic period to imagine a better world, a green economic recovery, and a closer connection with nature and biodiversity. The visual conversation that this new generation of artists created provides a lens for engaging with a world in change. They generate inspirational and resourceful ideas, calling on us to be participatory and inclusive as a fundamental aspect of being human, evoking imagination to create alternative visions in collaboration with others. New understandings through visual research can provide a foundation for developing collective strategies toward economic and social security, and flourishing individually and as community.

Keywords: visual research, green recovery, climate resilience

Introduction

The world is experiencing two catastrophic events in tandem-the growing impacts of climate change and the rapid rise of morbidity and mortality from the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. While both are extremely damaging physically and psychologically, they also attest to the resilience of a new generation of young adults at a time of deep uncertainty, as well as to their capacity to envision a better world. This article examines one such initiative; visual art students in South Africa used the pandemic period to imagine a better world, a green economic recovery, and a closer connection with nature and biodiversity.

During the height of the pandemic, the Canada Climate Law Initiative (CCLI) of the University of British Columbia (UBC), in collaboration with Artist Proof Studio (APS) and the University of Johannesburg (UJ), asked art students to create a "visual conversation" on the impacts of climate change and their hopes for a safe future. The two coauthors, professors in visual art and law, respectively, identified a gap in the extant literature in terms of the contributions that visual art can make to our cognitive understanding of the profound challenges posed by climate change, and the hopes of a younger generation that they can shift the trajectory of this threat to humanity. APS is a community art centre in Johannesburg cofounded by coauthor, Kim Berman in 1991 that raises funds to subsidise development of artists with passion and talent who do have the financial means to attend university. APS collaborates closely with UJ's visual art department. CCLI examines the legal basis for effective climate governance, including fiduciary obligations; it is situated on the ancestral territory of the xwmdûkwdydm [Musqueam Peoples]. CCLI scholars' research is grounded in notions of fairness and equity in examining the obligations of corporations, governments, and civil society to work collectively to create a sustainable future, drawing on theorists such as Amartya Sen (Sarra, 2020).

Climate Change and the Hope for a Green Recovery (https://artistproofstudio.co.za/pages/climate-change-the-hope-for-a-green-recovery) inspired a powerful set of images and conversations across the globe. The images express the artists' feelings of instability, despair, anger, and optimism, and communicate everything from deep knowledge of the devastating physical effects of global warming to messages of hope and resilience.

Visual arts can serve to raise awareness, foster positive social change, and serve as a mediating tool to improve understanding of different living circumstances. Art is intimately connected with a deeper understanding of the human condition and our capacity to be resilient in the face of extraordinary adversity. South African jurist, Albi Sachs, referring to his time in exile in Mozambique, described art as life, as death, as hope, and as despair (as cited in LeBaron, 2018). Recent neuroscientific research has found that art directly impacts our intellectual and emotional responses and how we see the world (Sarra, 2018). Art can be empowering during perilous life circumstances because it reminds us of the strength of the human spirit to transform internal and external realities, encouraging us to have faith in our ability to make a difference (McNiff, 1981). Nicholas Mirzoeff wrote that visual culture allows us to "understand change in a world too enormous to see but vital to imagine" (2015, p. 3).

Methodology

This project formed part of The Lockdown Collection, a civic campaign by and for artists, which raised over 2.5 million rand, distributing over 500 grants to vulnerable artists and art students during the first six months of the South African lockdown. The multifaceted campaign was not established as a research project, but it provides a valuable case study to reflect on deeper insights into ways that visual research pedagogies can develop collective strategies toward individual and community flourishing. We have treated artists' quotes below as if they were quotes from research participants.

The process of initiating the project was integrated into the online and blended learning programme at APS. Coauthor Janis Sarra provided the students with research on climate change drawn from the extensive scientific literature and United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG). Kim Berman convened colleagues and young artists at APS to design the competition. APS teachers prepared art-material kits, including smartphone devices that enabled students to load data and access voice notes and references on climate change. A young activist, Maru Attwood, shared examples of climate change activism in South Africa, and engaged the educators and students on different methods of creating awareness. The students had 10 weeks to develop their vision, supported by APS faculty through discussions on climate change research, artistic direction, and use of different materials.

The students viewed their Green Renewal portfolio as a means of visual action for social change. Each student from first- to fourth-year level was invited to participate by responding to their own environment and story. Thirty-five works were submitted, and the final selection was voted on by a committee of seven teachers, student representatives, and a guest environmental activist. The final round involved the authors identifying core themes revealed by the students' poignant artworks. Sixteen images, generated from photographs, collage, drawing, painting, or home techniques of printmaking were professionally photographed and digitally printed in limited editions. Each of the final works in the portfolio was accompanied by an artist's statement and video clip and released on social media as a knowledge-sharing campaign for climate change and green renewal post-pandemic. Their art formed the centrepiece of a discussion on climate change at a virtual CCLI-hosted international research roundtable in September 2020. The powerful visual expression was paired with narrative to illustrate the daily impacts of climate change as it intersects with the structural violence of poverty, abuse, and environmental neglect that young people are facing. As Mirzoeff might describe, the project was not aimed at being a comprehensive mapping of capitalised/visualised materials but, rather, deployed visual activism as a means to map change and then make social change, using contextual expressions of the artists' own living conditions (as in Barreiros, 2017).

Visual research has long been a methodology for the visual arts. It became essential during the lockdown period, when art students were not permitted to attend class and thus were required to deeply examine the visual world they inhibit in order to identify their insights on climate impacts. The artists provided informed consent for their participation in the project and the sharing of their intellectual and artistic property. It was an iterative process, each image powerful on its own, with the reflective descriptions adding further depth and insights into their representations of the climate crisis amidst a global health pandemic. Proceeds from sale of the artworks helped support these artists through the pandemic and directed funds to the South African Vulnerable Artist Fund.

The works by the student artists illustrated in this article represent a selection of those presented at the CCLI conference. Each student gave their consent to use their text in subsequent platforms consistent with their interest in "artivism" or visual activism. The authors have linked images and themes without always explaining associations, leaving the reader to imagine possibilities and the images to activate their potential in these particular contexts (Bal & Bryson, 2001).

Tumisang Khalipha's Bokgakala (Beneath) introduces the visual conversation (Figure 1). Born in the rural village of Mahikeng, Khalipha wrote:

My work explores the dangers of chemical waste In oceans, dams and rivers. This water pollution kills these beautiful creatures as they ingest the litter and toxins dumped in the water. My work captures the environmental loss of a home and food for aquatic creatures.

His visual exploration of damage to the environment is then linked with damage to humans, with Figures 2 and 3 capturing the inward and outward effects. Khalipha draws inspiration from his father, a miner, and the need for villagers to collect water from polluted streams and open casts, with children often getting sick from contaminated water. Khalipha talks about using his artwork to search for "inner peace and purification" as his physical relocation and his health have improved. His etchings explore the water pathways in the body as a metaphor for the imperative of transformation to maintain the health of our environment and ourselves.

Differences in how we, collectively, individually, globally, tackle these issues will continue to exist, but the visual arts offer opportunities for new understandings and new exchanges that can assist in creating policies aimed at fairer and more equitable outcomes.

Convergence of Catastrophes

Climate change has been identified by the World Economic Forum (WEF) as the top economic risk globally, with economic damage totalling US$165 billion in 2018 (WEF, 2020). Internationally, courts have found that anthropogenic (human-caused) global warming poses an existential threat to humanity (Ontario Court of Appeal, 2019). As 197 countries agreed under the 2015 Paris Agreement, there is urgent need to reduce annual emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) by 2030 if we are to have any hope of holding the increase in global average temperature to below a level in which humanity can survive (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015). Six years on, as the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) approaches, progress towards decarbonisation is slow, and the impacts of climate change are being felt everywhere, particularly in emerging nations such as South Africa.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2018), representing consensus of over 800 scientists on behalf of 150 countries, has reported that human-induced global warming has now reached 1°C above preindustrial levels, with some impacts, such as loss of ecosystems, predicted to be irreversible. The IPCC (2018) reported that without drastically stepping up climate action, global average temperature increase could reach 1.5°C within eight years and continue rising, significantly increasing risks associated with sea-level rise for many human and ecological systems. A 2015 empirical study in Nature concluded that globally, a third of oil reserves and over 80% of current coal reserves should remain unused in order to meet even a target of 2°C warming (McGlade & Ekins, 2015). Climate change represents a significant risk in financial markets, yet while corporations and institutional investors are moving towards commitments of net-zero GHG emissions, progress is deeply uneven across the globe (WEF, 2020).

Even as climate change becomes urgent, the COVID-19 pandemic has surpassed it in its immediate and profound impacts. Globally, 183 million people had contracted COVID-19 and 3.9 million died-and in South Africa, over 2 million had fallen ill and 61,000 died-as of June 2021 (Johns Hopkins, n.d.). Wooyoung et al. (2020, p. 1) asserted that

for millions of South Africans, vulnerability to COVID-19 Infection Is amplified by other preexisting adversities, such as hunger and violence, an overburdened healthcare system, a high prevalence of chronic and infectious disease, and alarming rates of poverty (55.5%) and unemployment (29%).

In the Global North, citizens' confidence about security has been deeply challenged. In the Global South, communities are far less equipped to control the pandemic's spread and must cope with the serious consequences of lockdown, the economic effects of which will reverberate for years. Student artists have lived the lockdown in South Africa without access to any water, some living in abusive situations, others having to sell phones or other possessions for food, losing the ability to connect to classes or peers. The "mental health consequences caused by the rapid and dramatic societal changes from the lockdown, however, cannot be overlooked in a country with considerable psychiatric morbidity, limited mental healthcare infrastructure, and high rates of poverty" (Wooyoung, et al., 2020, p. 1).

The combined catastrophes of COVID-19 and climate change are having severe health impacts on youth globally. Yet new vulnerabilities have inspired a spirit of community and compassion. It may open new windows of opportunity for meaningful dialogue and, hopefully, change. The pandemic has reminded us not only that global crises demand swift and coordinated international responses, but also that profound social, environmental, and economic change can happen quickly. These reminders offer hope that our global community can tackle climate change.

Art as Resilience

Visual arts can open dialogue and deepen our understanding of the inequities associated with a warming planet. The Global North and South can learn much from one other through a visual conversation about climate change impacts and potential for a sustainable and equitable economic recovery. The arts are particularly important in South Africa for offering the space to address deep wounds, using artistic collaborations to contribute to resilience and wellbeing (Sarra & Berman, 2017). As LeBaron has observed, "the arts are being embraced with increasing urgency and legitimacy, both as resources for development work and as ways to recover from trauma and revitalise individual and community life" (2018, p. 1). Artists have "the power to reveal the underlying meaning of any period precisely because the essence of art is the powerful and alive encounter between the artist and his or her world" (May, 1975, as quoted in Gupta, 2020, p. 601).

The COVID-19 pandemic has been exceptionally devastating for young artists, who often live in deep poverty. The artists here offer poignant insights into the impacts of global warming, generating a visual conversation that focuses on decarbonisation and vastly increased food and water security as the way forward. These powerful images have generated new insights, new conversations, and new hope that this existential threat can be overcome.

Including the arts in policy discussions, as an integral part of understanding climate change, attests to how a visionary approach is needed to influence policymakers. When artists are included, they bring a range of values, including aesthetics, multiple modalities, imagination, alchemy, and reciprocity-all of which deepen and enrich understandings and, ultimately, social change outcomes. Action based on science is essential, but so too is imagination, and the visual arts can transform despair into hope and vision. The visual conversation that these talented artists created provides a lens to engaging with a world in change. Their visions are of ongoing hard lessons of renewal, adjustments, and resilience. Their ideas continue to reverberate globally, opening dialogue with business and government about the responsibility that comes with having benefited economically from a carbon-intensive world. Visual responses to climate change can continue to open dialogues with business and government who have direct responsibilities for the damage resulting from a carbon-intensive world, as the next section demonstrates.

The Impacts of Climate Change Storms are Increasing in Frequency and Severity

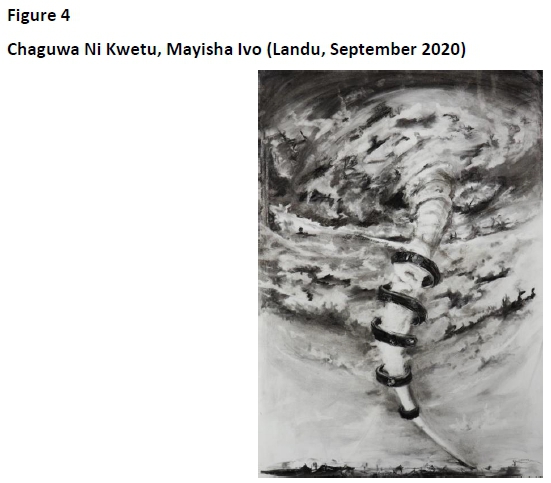

Global warming is resulting in increasing frequency and intensity of acute climate-related events. Coastal communities are exposed to multiple climate-related hazards, including intense tropical cyclone winds, tornados, extreme rainfall, storm surges, and sea-level rise (IPCC, 2019b). Figure 4 poignantly demonstrates the devastating effects of increasing tornados destroying homes and lives.

Artist Tusevo Landu was born in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and currently resides in South Africa as he completes his third year at APS. In his artist's statement regarding Chaguwa Ni Kwetu, Mayisha Ivo [The choice is ours, so is the life], he writes:

In my work, I present a drawing of future weather conditions in our continent. Climate change will have catastrophic negative effects on our weather in Africa. We Africans have already been experiencing extreme weather conditions because of global warming. In the past, tornadoes were not a part of African weather conditions and were only seen in other continents. In the near future, tornadoes will become part of both urban and rural weather patterns, caused by global warming. I have hope for the improvement of our world because we can use more environmentally friendly products to save the earth, benefiting everyone's health and environment.

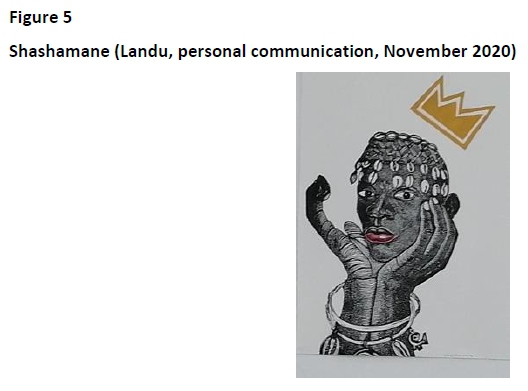

Landu has used his visual voice to speak out against the severe ongoing cycle of exploitation of the Congolese people, their suffering, and mutilation of their land's vast natural resources. He points to child mining, the extinction of animal species in the Congo region, and how the world benefits from technology at the expense of nature-illustrated by his linocut (Figure 5).

Another result of acute climate-related events is increased flooding, making homes uninhabitable, and displacing thousands of people. Impacts associated with sea level rise are loss of freshwater due to ocean inundation into rivers, increased flooding and damage to infrastructure, and flooding rendering small islands and low-lying coasts uninhabitable (IPCC, 2019a). Businesses are being forced to relocate and migration is increasing as populations begin to search for safer places to live.

Cinthia Sifa Binene's In Your Space (Figure 6) highlights that climate change acts as a leveller-the interior of a luxurious home is flooded. While, to date, climate change has disproportionately affected the poor, as its impacts accelerate, no one is protected.

Born in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo in 1997, Sifa Binene's image reflects the magnitude of the damage, and how tiny we are in the face of impending climate impacts. She writes:

We can no longer hide in our fancy homes and pretend only poorer communities of people will suffer the effects of climate change. In using collage, I was able to deconstruct and reconstruct the devastation and chaos of the present and future . . . the act of collaging mimics the tearing apart of our environment because of our actions. The plastic packaging floating in the water is plastic waste generated from the beauty and cosmetic industries, most of which is not recyclable, takes longer to decompose, and generates methane gas into the atmosphere, harmful to the environment and contributing to heating up of the earth. We, as women, who are consumers of these products, should think about the harm they produce on the planet.

Sifa Binene's work draws from her feelings of displacement as a Congolese woman living in South Africa, and the multiple identities she is expected to fulfil. Her visual sophistication of recycling waste materials as collage elements in her artwork, illustrated by the materials in Figure 7 combined with her commitment to exploring women's empowerment and agency, position her to be an important emerging African voice on these issues.

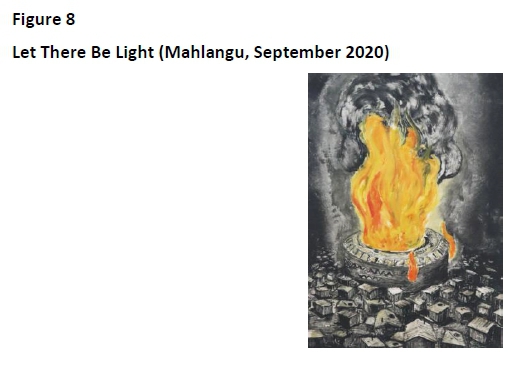

Air pollution is now exacerbated by global warming. Increased energy demand and production increase anthropogenic air pollutant emissions, causing hundreds of thousands of people, especially in developing nations, to die prematurely every year (IPCC, 2018). Lucky Bongani Mahlangu's print (Figure 8) graphically illustrates how burning fossil fuels and car tyres contribute to global warming and environmental destruction.

An emerging artist and printmaker from Ekurhuleni, Gauteng, Mahlangu highlights how air pollution dominates the daily lives individuals living in communities situated in the shadow of major polluters:

My artwork highlights how the burning of oil, coal, and car tyres contributes to air pollution. With the incompetence of the state failing to provide sustainable energy leading to load-shedding, it results in people having to make their own way to ensure they have light and heat. I use colour to depict the element of fire and a monochrome palette to introduce the feeling of darkness or load-shedding. I try to depict the dark aftermath of the human race if we do not change the way we treat nature. I reference images from my surrounding reality.

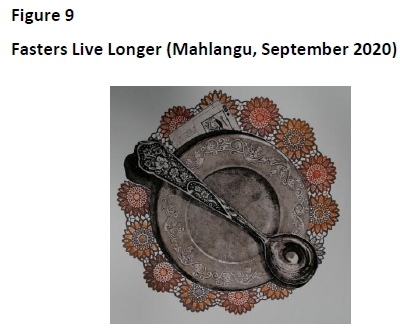

Mahlangu's sensitive work speaks out against the hardships that he and his mother, a single parent and breadwinner, experience. His artist's statement refers to the failure of the state in securin g the basic needs of clean water and air. Despite poor living conditions in shacks, Mahlangu pays tribute to the beauty and grace of simple household objects such as the spoon, honouring his mother's story (Figure 9). His work shines a light of hope in the some of the darkest places.

Africa is particularly at risk because of the high rate of climate-sensitive diseases and low response capacity at the institutional and community levels (World Meteorological Organization, 2020). Older people are more likely to suffer from health conditions that limit the body's ability to respond to stressors such as heat and air pollution (Smith, et al., 2014). Figure 10 is a powerful reminder that people living in conditions of extreme poverty and pollution experience climate impacts every moment of every day.

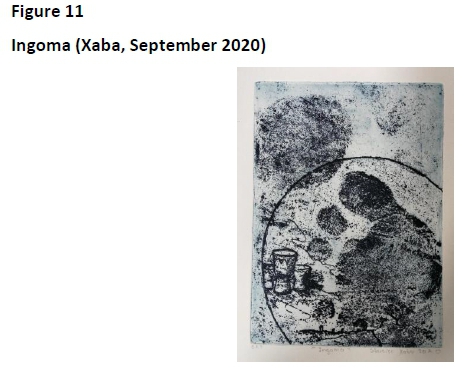

Artist Sibusisu Xaba was born in Soweto. His digital image reflects extremely difficult living conditions that are exacerbated by air pollution. Xaba writes:

My home is dumping ground for human waste with factories In the distance. In my community there is litter everywhere and people burn their trash to get rid of the litter, but it pollutes the air we breathe, later making us sick. In our squatter camp, we don't have electricity. People burn wood to cook and keep warm. There are no trees because we have cut them down to use as firewood. No evidence of nature anywhere, where I live in Nomzamo Park. People are just trying to survive.

Xaba's living conditions, and his inability to find food security during the COVID-19 lockdown, led him to turn to Indigenous cultural knowledge to explore renewal through his artwork, particularly exploring Ingoma, a traditional Zulu dance that young men and women perform to prepare their bodies for transition ceremonies. This dance becomes a metaphor of his own resilience for survival. Figure 11 is an aluminium etching of Ingoma and the idea of creating art through nature. The etching is a process of pushing his own footprint into soft ground to record the imprint onto an aluminium plate, which is then processed using copper sulphate salts as a saline etch. This process is "green" printmaking that has allowed the students to explore safely in their own home environments over the lockdown. Finding green ways of practising printmaking carries a powerful message that can at once change behaviours and advocate for safe and Indigenous approaches to change.

Companies can make a profound difference in preventing the devastating health effects of pollution. They can drastically reduce GHG emissions and associated co-pollutants in their production and distribution by using new technologies and cleaner renewable energy, in turn reducing chronic and acute respiratory illnesses, lung cancer, and preterm birth (Smith et al., 2014). In particular, massively reducing coal mining and combustion would reduce many health-damaging emissions.

Water Security is Essential

Fresh water is a fundamental resource for natural ecosystems and human livelihoods, and access to it is considered a universal human right (Sarra, 2020). About one half of the world's population is projected to face water shortages by 2030, with demand exceeding water supply by 40% (UN, 2019). Globally, 2.2 billion people still lack safely managed drinking water and more than 840,000 people die each year from a water-related disease (UN, 2020), which means that it is not only water scarcity that is a critical risk to human life, but access to safe water is crucially important. The image by Clement Mohale (Figure 12) is a poignant message regarding the need for water security, highlighting the devastating effects of climate change on agriculture and the hope of new generations for a more symbiotic relationship with nature.

Land degradation, decreasing water resources, loss of biodiversity, and excessive use of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides are some of the environmental challenges that influence preparedness to adapt to climate change (IPCC, 2019a). Increasing urbanisation is reducing the amount of land available for growing crops. Mohale observes:

Access to improved drinking water is still a challenge in African countries, which has had a terrible effect on the deaths caused as a result of its need. Therefore, with the current COVID-19 pandemic, the situation can drastically worsen as sanitisation is important during this devastating time. It is essential that we learn the importance of preserving the environment that we live in by being eco-friendly, so that the next generation does not bear the catastrophe we have left behind.

The life-threatening need for water is illustrated by the devastated landscape, but, as Mohale's title indicates what we take from nature, we must give back.

In another work by Mohale, the figure holds out a pill to a personification of the coronavirus as if to say, "Can this provide a cure?" (Figure 13). The drawing highlights the lack of available vaccines. One can intuit different meanings for the box-shaped head, possibly that decisions as to who is given priority in addressing health and water stresses are made in a "black-box" by faceless decisionmakers under opaque rules. Mohale's artwork is a call to action-access to clean water is critical, not only for hygiene during the pandemic, but for life itself.

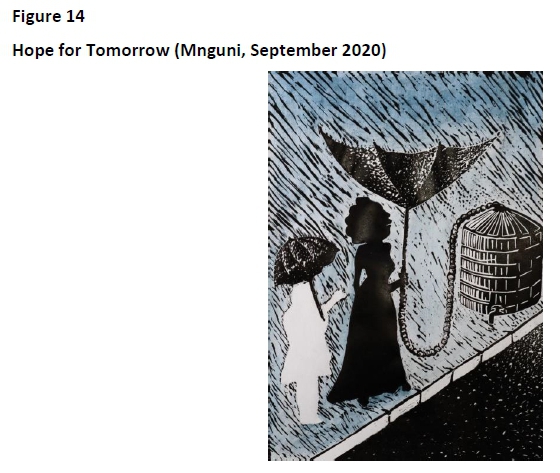

The next image, Figure 14 by Gugulethu Mnguni, shifts the conversation from severe water shortages to new collaborative strategies to create water security, suggesting that we can capture nature's gifts to begin to address water security.

About Hope for Tomorrow, Mnguni writes:

A few years ago, Cape Town struggled with water shortages. In 2017, there were Level 7 water restrictions, where the municipal water supplies would be switched off and residents would have to queue for water. The artwork here is about one's ability to save water. The black and white figures represent different races of people. In the work, I am trying to convey that whatever your race is-whether black or white-you should be able to value water and never pollute in it. The colour blue represents a hope that, at the end of the day, it will all be okay. We will all look back at these hard times and rejoice that we made it through. I use the upside-down umbrella as a metaphor showing the struggles that we all face, not just Cape Town alone, but the whole world this year.

Mnguni's image is powerful and hopeful. She highlights the need for all races to work together to protect the planet's fresh water and to share access to it equitably.

The UNSDG seek to achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all by 2030, recommending that we improve water quality by eliminating dumping and minimising release of hazardous chemicals; ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity; expand international cooperation and capacity-building support to developing countries, including water harvesting, desalination, reuse technologies; and strengthen participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management (UN, 2020). As with Mnguni's Hope for Tomorrow, we need to be innovative and forward looking in policy choices that will secure safe water for millions, globally.

The Need for Rapid Decarbonisation

There is need for rapid decarbonisation of the planet if we are to protect humanity from extreme heat waves, water scarcity, and permanent loss of biodiversity. GHG emissions are a prime driver of rising global temperatures and thus must become a key focal point of policy, regulatory, market, and technology responses. Scientists have stressed that if we are to avoid "tipping points" beyond which humanity cannot survive, we need to take immediate and deep decarbonisation action (Houghton et al., 2001, p. 6).

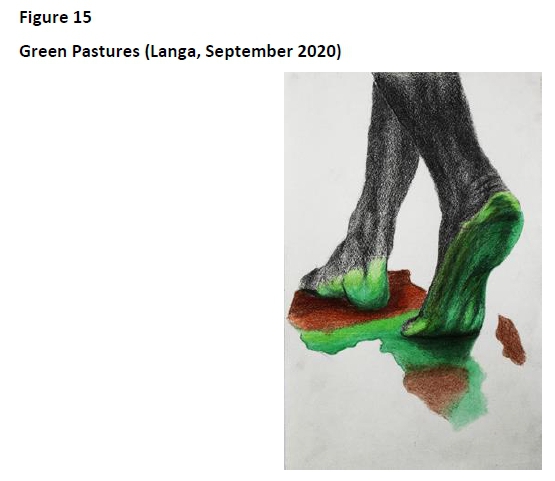

Jason Langa's Green Pastures (Figure 15) is a powerful evocation of the notion that our carbon footprint needs to radically change from one that is carbon intensive to one that embeds nature and sustainability in each step. The green footprint over Africa is an iconic visual call that Langa presents as a challenge for action. It is evocative of the beauty of the land and human capacity to reduce our carbon footprint.

Langa writes:

In Greener Pastures, focus is on promoting habits that could help to slow down or even halt the effects of climate change, including activities that seek to reduce our carbon footprint and the detrimental effects which our everyday lives have had on the planet. Activities that could help with this reduction include driving less, using water sparingly, recycling waste materials, and switching to renewable energy. Reversing the effects of climate change can be possible by working together as a planet.

Decarbonisation strategies include generating, storing, and using clean renewable energy, improving energy efficiency, phasing out fossil fuels, and establishing energy infrastructure to enable decarbonisation (Sarra, 2020). It requires an entire systems approach, from our daily industrial activities and supply distribution strategies to our personal choices such as how we travel (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2020).

In South Africa, one challenge is that two million businesses are micro, small, or medium enterprises (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2020). They require infrastructure support to transition to decarbonisation of production, including information and financial support to adopt energy efficient and renewable technologies, resources to retrofit buildings, and to facilitate partnerships with businesses to design waste out of productive processes (Sarra, 2020).

Protecting Food Security and Biodiversity

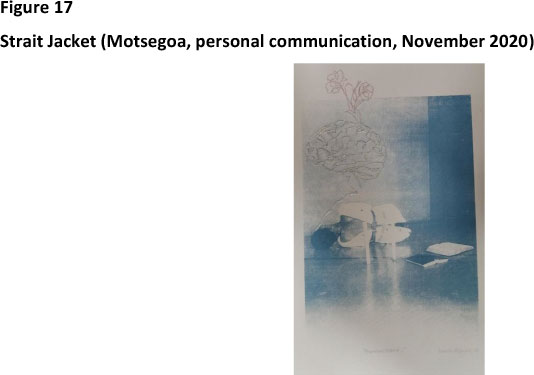

Climate change is already affecting food security through increasing drought, loss of arable land, changing precipitation patterns, and extreme heat, with temperatures in 2019 frequently exceeding 45°C in parts of South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique (Sarra, 2020). Drought affected parts of Africa in 2019, with rainfall less than half of the average in most of the western half of the continent (World Meteorological Organization, 2020). There is severely damaged production capacity of staple crops and biodiversity loss is growing rapidly, creating severe food insecurity and malnutrition in Africa for 29.8% of the population (Sarra, 2020). Africa cannot grow enough food to feed its rapidly growing population. Climate change has strong gender and equity dimensions, given the huge role women play as the primary producers of food from the land. Amanda Motsegoa portrays these powerful images in Rebellion and Rebirth (Figure 16).

Born in Soweto, Motsegoa writes:

Most plants and animals survive under strict climate conditions. Temperature and water supply enable them to thrive. Changes in the climate can greatly affect the production of agriculture in some areas. In this work, I depict how one solution to reduce the effects of climate change can overturn the future of agriculture and our extreme climate conditions.

Motsegoa's art explores survival and resilience. As a young woman living with depression, her artist's statement reveals some of this despair and hope: "I live my life wrapped in an invisible straitjacket as an aid to my own self destruction and as a façade to the rest of the world". This powerful and painful message must extend to a deeper understanding of self and environmental protection (see Figure 17).

Negative impacts of climate change on vegetation affect all four pillars of food security: availability (yield and production), access (prices and ability to obtain food), utilisation (nutrition and cooking), and stability (disruptions to availability) (IPCC, 2019b). Scientists urge coordinated action to address climate change to simultaneously improve land, food security and nutrition, and help to end hunger.

Companies have a role and responsibility to provide economic support that will build capacity of peoples in emerging nations to develop resilient production, including strategies to produce food while preserving ecosystems based on conservation agriculture, more effectively manage rainwater and water use, and implement new economic models that enable youth and women to access credit. These strategies should build on local knowledge, culture, and traditions. Transformational adaptation is needed, including better storage and food processing, adoption of harvest technologies that minimise food waste, and development of new opportunities for farmers to respond to environmental and economic shocks (IPCC, 2019a).

Renewable Energy

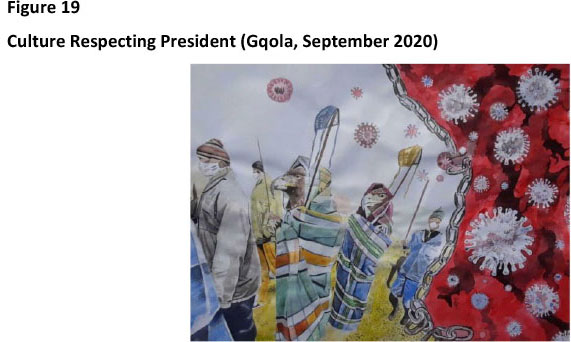

Protection of biodiversity and food security are deeply linked to shifting to renewable energy sources. Both governments and the private sector need to act with some urgency to scale-up net-zero carbon technological innovation and move in a meaningful way towards renewable energy sources (Sarra 2020). Solar energy is the most abundant renewable energy source, yet it still only represents a small fraction of total energy (IPCC, 2019a). Samukelo Gqola's inspiring watercolour (Figure 18) draws together Xhosa tradition and culture and advocacy for renewable energy as a key mechanism to combat climate change.

Of Wind of Power, Gqola writes:

My work focuses on migration and how people have to migrate and move towards a future with renewable energy sources. In my work, I also pay tribute to my grandmothers' Xhosa tradition and culture as I was raised in Eastern Cape, South Africa. I created this work in response to climate change, which shows how Indigenous people and culture are under threat from global warming. We need to migrate and to embrace new clean energy to be able to preserve our Xhosa culture and sustain living off the land. The Xhosa male figure with a windmill head is wearing a blanket as a symbol of protection. It is a difficult time for human beings and creatures because of global warming and climate change. There are ways to prevent these challenges and protect the earth, but we need the government to be on our side.

Gqola uses initiatory symbolism in Figure 19, transitioning in time and space, anticipating a future of transformation. Eagles and other large raptors are represented in this artist's work, symbolic of far-seeing vision, wisdom, and nobility of spirit.

The deep interlinkages between global warming, forced migration, and protection of Indigenous rights are poignantly illustrated in this powerful piece. Indigenous peoples are stewards of the earth and provide leadership in renewable energy projects that protect land, air, and water, while creating employment (Sarra, 2020). Solar technologies can improve the health and livelihood of many of the world's poorest populations by closing the gap in availability of energy services for 1.4 billion people currently without access to electricity. Most areas in South Africa average 2,500 hours or more of sunshine per year, and solar and wind energy are readily accessible resources (South Africa Government, 2020).

While the potential is tremendous, the challenge is how to distribute the social and economic benefits of renewable energy in a fair and equitable way. Renewable energy cannot simply benefit the propertied, and both public and private resources must be utilised to afford many communities access to safe and affordable renewable energy and the employment it generates.

The Move to a Circular Economy

The term "circular economy" envisions a new approach to economic activity in which the existing paradigm of produce-use-recycle or trash is replaced with a much more sustainable framework that seeks to use only renewable energy and natural production components that can be returned to the earth after productive use. It designs the eventual elimination of waste into the system of production (Sarra, 2020). The goal is net-zero carbon emissions and the use of any production outputs (formerly waste) in new productive activities.

Artist Anthony Sithole of Alexandra, Johannesburg pays tribute to local recycling pickers in Daily Dance (Figure 20), observing that:

In Alex, we have recycling guys who come around to collect our plastic waste every day of the week. They help us get rid of our waste and they get some money to survive, in order to use it to eat and feed their families. They have a hard job, but they help keep Alex clean.

Sithole, a young artist living with a disability, is moved by the waste pickers who control the pollution in Alex. This green renewal initiative assisted him to focus and consolidate his personal advocacy of recycling and waste management at his special needs school. His linocut (Figure 21) speaks to the waste pickers dressed in space suits of protective clothing as heroic science fiction figures overcoming contamination and making the environment safe for humans and animals (Figure 22).

There are inspiring examples of circular economy activity in emerging nations. China's Circular Economy Promotion Law requires factories to embed themselves in a circular network; its Rizhao eco-industrial park is one of a growing number in which 98% of solid waste has been eliminated because it is reused in other production (Sarra, 2020). The artists' images, which spark the imagination, help us to visualise a future that eliminates waste and distributes economic benefits more equitably.

Justice Requires Economic Recovery To Be Fair and Equitable

The young, "born free," generation of urban black poor of the townships have been betrayed repeatedly by the promise of the new South Africa. The hope for a productive future and green renewal ultimately rests with this emergent generation.

Fairness can inform how we link strategies to reduce emissions with efforts to design and redeploy materials used in every sector. Yet there is need to reach meaningful and equitable decisions between different governments on decarbonisation and on achieving the UNSDG. "Fairness and public interest doctrines can serve as guideposts and principles for effective climate governance of companies, institutional investors, and the national authorities that regulate their activities" (Sarra, 2020, p. 142). Perspective-taking can deepen our understanding of climate change and its relationship to corporate governance and financial markets and encourage a substantive aspirational goal of more equitable treatment of individuals differently situated (Sarra, 2020).

The visual arts can help reveal that vision of fairness, of conceptualising a world that is "other regarding," taking account of others' needs and perspectives in envisioning a more sustainable planet. Simphiwe Dlamini, born in KwaZulu-Natal, challenges us to imagine a better world. Imagine (Figure 23) is evocative of a planet in which pollution can be replaced with clean air, trash with plants, and petrol with power that is renewable.

Dlamini uses images that express a fantasy of exuberance and abundance of colour. The scale and style of the landscape is reminiscent of children's illustrated fairy-tales. However, the girl at the edge of the water is faceless and her arms burnt, possibly from exposure to toxins. The fish are held in a precarious safety net that could be spilt onto the earth. Things are not as they seem. She compels us to imagine a more beautiful and hopeful earth.

While we are amid concurrent catastrophes, it is difficult to envision a fair and just economic recovery but, equally, it is essential to undertake exactly that project. There is need for public-private cooperation, but where public resources are expended, there need to be guarantees that the benefits accrue fairly and equitably to a wider range of people, particularly Indigenous and racialised people and women (Sarra, 2020). Here, the South African concept of ubuntu and its relationship to the visual arts may guide our path.

Elsewhere, we have explored ubuntu and its relationship to resilience (Sarra & Berman, 2017). Arguably, ubuntu can be used as a guide to a new conversation about fairness and equity in developing climate resilience. As Thaddeus Metz (2011) has observed, ubuntu is experiencing life as being bound up with others and considering oneself a part of the whole. This notion of being part of the collective, making decisions with a view to both individual and collective well-being, grounded in ethical considerations, offers a starting point for thinking climate governance (Sarra & Berman, 2017). Both the COVID-19 pandemic and the devastating risks of climate change provide poignant evidence that we are inextricably bound to one another. Beginning this visual conversation from South Africa on hope for a green recovery, we acknowledge that our own good is intertwined with the good of others. Ubuntu can serve to support resilience and inspire individuals to actively and collectively engage with one another to address the challenges-and, hopefully, can inspire thriving rather than simply surviving.

The images created by this new generation of artists let imagination and play give the space to conceive new ways of seeing. They call on us to be participatory and inclusive as a fundamental aspect of being human, evoking imagination to create alternative visions in collaboration with others. Coauthor Sarra has written:

Countries in the Global North, which have caused the vast majority of emissions, need to direct significant resources to the Global South, which is experiencing the most devastating impacts of climate change. Such financial support can produce positive synergies for all countries, but cannot be structured in a manner that fails to empower emerging nations to make their own decisions, control their own resources, benefit from circular economy innovations, and protect their own populations. It needs a massive shift to the circular economy, to literally save our planet. It requires that all of us become stewards of the earth. (2020, p. 312)

We are not underestimating the profound challenges. We understand the powerful economic forces at play and the huge stakes for humanity. We understand that consensus will not be developed in the short term. However, as economist Amartya Sen observed, there are "inescapable plurality of competing principles of social justice that may conflict with one another," which must permit partial agreements on issues of justice, making room for incompleteness and diversity of inputs, with a view to creating greater fairness informed by "vaguely shared but far-reaching concerns about injustice and inhumanity that challenge our world" (2009, pp. 90, 107-9). What he articulated over hundreds of pages, our young artists have captured with the images we share here.

Business, government, and civil society all have a critically important role in this urgent global imperative. Those who have long benefited from the revenues that high-carbon-emitting activities have generated must act quickly to decarbonise their activities and move to sustainable activity if there is to be any hope of reversing the mounting effects of climate change. We need to develop solutions that can bridge the gap between corporate and community visions of a safer, fairer, and sustainable planet going forward.

Conclusion

The visual arts nurture and enliven our humanity; they facilitate the imagination, enrich resilience, and create spaces for hope and self-reflection. The art students represented in this green renewal portfolio see themselves as agents for change. Their voices enable us to see the urgent calls for renewal, the complexity and the agency to transform the challenge of hardship into one of opportunity. Each work is a reminder of what we need to do to make changes in our own lives. The visual arts can transform despair into hope and vision, working with science-based climate-related evidence to build crucially important strategies for protecting humanity. These artworks assist in contributing to the vision for environmental and economic activism and justice. Let us actively engage with possibilities for a new future. Artists can lead the way in the search for new and imaginative possibilities for change.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks to Rene Mathibe (Figure 24), teachers, and students of APS for their creative insights, and to PWIAS and CCLI for funding support. All images and statements are used with the artists' permissions.

References

Bal., & Bryson, N. (2001). Looking in: The art of viewing. Routledge.

Beleza Barreiros, I. (2017). "Theory" is not just words on a page. It's also things that are made: Interview with Nicholas Mirzoeff. BUALA. https://www.buala.org/en/face-to-face/theory-is-not-just-words-on-a-page-it-s-also-things-that-are-made-interview-with-nichol

Binene, C. S. (n.d.). In your space. Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/pages/climate-change-the-hope-for-a-green-recovery

Dlamini, S. (n.d). Imagine. Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/pages/climate-change-the-hope-for-a-green-recovery

Gqola, S. (n.d.a). Wind of power. Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/pages/climate-change-the-hope-for-a-green-recovery

Gqola, S. (n.d.b). Culture respecting president. The Lockdown Collection. https://www.thelockdowncollection.com/student-collection/samukelo-gqola

Gupta, N. (2020). Singing away the social distancing blues: Art therapy in a time of coronavirus. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 60(5), 593-603. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167820927807 [ Links ]

Houghton, J. E. T., Ding, Y., Griggs, D., Noguer, M., van der Linden, P., Dai, X., Maskell, M., Johnson, C. (2001). Climate change 2001: The scientific basis. Third assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2019a). Climate change and land. https://www.ipcc.ch/2019/08/08/land-is-a-critical-resourcesrccl/

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2019b). Impacts of 1.50C global warming on natural and human systems. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/chapter-3/

Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. (n.d.). Coronavirus resource center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/

Khalipha T. (n.d.a). Bokgakala (Beneath). Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/pages/climate-change-the-hope-for-a-green-recovery

Khalipha T. (n.d.b). Rising up. Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/collections/i-24-unmasked

Landu, T. (n.d.). Chaguwa ni kwetu, mayisha ivo. Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/pages/climate-change-the-hope-for-a-green-recovery

Langa, J. (n.d). Green pastures. Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/pages/climate-change-the-hope-for-a-green-recovery

LeBaron M. (2018). Introduction. In M. LeBaron & J. Sarra (Eds.), Changing our worlds: Art as transformative practice (pp. 1-22). Sun Press.

Mahlangu, L. B. (n.d.a). Let there be light. Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/pages/climate-change-the-hope-for-a-green-recovery

Mahlangu, L. B. (n.d.b). Fasters live longer. Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/collections/i-24-unmasked

McGlade, C., & Ekins, P. (2015). The geographical distribution of fossil fuels unused when limiting global warming to 2°C. Nature, 517, 187-190. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14016 [ Links ]

McNiff, S. (1981). The arts and psychotherapy. Charles Thomas.

Metz, T. (2011). Ubuntu as a moral theory and human rights in South Africa. African Human Rights Journal, 11(2), 532-559. http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/ahrlj/v11n2/11.pdf [ Links ]

Mirzoeff, N. (2015). How to see the world. Pelican.

Mnguni, G. (n.d). Hope for tomorrow . Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/pages/climate-change-the-hope-for-a-green-recovery

Mohale, C. (n.d.a). From nature we take and to nature we give. Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/pages/climate-change-the-hope-for-a-green-recovery

Mohale, C. (n.d.b). Unprecedented times. The Lockdown Collection. https://www.thelockdowncollection.com/student-collection/clement-mohale

Motsegoa, A. (n.d.). Rebellion and rebirth. Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/pages/climate-change-the-hope-for-a-green-recovery

Ontario Court of Appeal. (2019). Reference re Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, 2019 ONCA 544. https://canlii.ca/t/j16w0

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2020). Financing SMEs and entrepreneurs 2020: An OECD scoreboard. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/37b75ad0-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/37b75ad0-en

Sarra, J. (2018). Conclusion. In M. LeBaron & J. Sarra (Eds.), Changing our worlds: Art as transformative practice (pp. 149-160). Sun Press.

Sarra, J. (2020). From ideas to action: Governance paths to net zero. Oxford University Press.

Sarra, J., & Berman, K. (2017). Ubuntu as a tool for resilience: Arts, microbusiness, and social justice in South Africa. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 34, 455-490. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.21192 [ Links ]

Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. Harvard University Press.

Sithole, A. (n.d.). Daily dance. Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/pages/climate-change-the-hope-for-a-green-recovery

Smith, K. R., Woodward, A., Campbell-Lendrum, D., Chadee, D. D., Honda, Y., Liu, Q., Olwoch, J. M., Revich, B., & Sauerborn, R. (2014). Human health: Impacts, adaptation, and co-benefits. In C. B. Field, V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, T. E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K. L. Ebi, Y. O. Estrada, R. C. Genova, B. Girma, E. S. Kissel, A. N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, & L. L. White (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability (pp. 709-754). Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5-Chap11FINAL.pdf

South Africa Government. (2020). Renewable energy: Solar and wind power. http://www.energy.gov.za/files/esources/renewables/rwind.html

United Nations. (2019). Water facts and figures. http://www.unwater.org/water-facts

United Nations. (2020). Sustainable development goals: Clean water and sanitation. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/water-and-sanitation/

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2020). Transportation air pollution and climate change. https://www.epa.gov/transportation-air-pollution-and-climate-change/carbon-pollution-transportation

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2015). Adoption of the Paris agreement. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf

Wooyoung, A. K., Nyengerai, T., & Mendenhall, E. (2020). Evaluating the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in urban South Africa: Perceived risk of COVID-19 infection and childhood trauma predict adult depressive symptoms. Psychological Medicine, First View, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720003414

World Economic Forum. (2020). The global risks report 2020. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2020

World Meteorological Organization. (2020). State of the climate in Africa 2019 report. https://unfccc.int/news/climate-change-is-an-increasing-threat-to-africa

Xaba, S. (n.d.a). Soweto. Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/pages/climate-change-the-hope-for-a-green-recovery

Xaba, S. (n.d.b). Ingoma. Artist Proof Studio. https://artistproofstudio.co.za/collections/i-24-unmasked