Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Educational Research for Social Change

versão On-line ISSN 2221-4070

Educ. res. soc. change vol.8 no.1 Port Elizabeth Abr. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2018/v8i1a4

ARTICLES

Inside a Box: Using Objects To Collaboratively Narrate Educator Experiences of Transformation in Higher Education1

Marguerite Müller

University of the Free State, mullerm@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article is a reflection on the use of object memory in creating a collaborative arts-based narrative that explores educator experiences with transformation in higher education. The collaborative arts-based narrative that I present here emerged from my doctoral thesis in which I collaborated with participants to explore how our memories and experiences could help us understand and approach issues of social justice in education. In this article, I reflect on the way in which memory objects guided the creation of a collaborative arts-based narrative of educators' autobiographical experiences, educational encounters, and anti-oppressive education. Memory objects are used to explore educator identity, subjectivity, and experience in relation to issues of social change and social justice in higher education. Through this exploration, I hope to highlight the entanglement of context, experience, and the theoretical understandings of social justice and anti-oppressive education. The aim of this article is to reflect on how objects were used to make new connections and exciting discoveries through a collaborative narrative of memories and experiences of educators working towards social change in higher education.

Keywords: anti-oppressive education, arts-based research, collaborative narrative, educator subjectivity, object memory

Inside a box . . .

"Draw me a sheep," said the Little Prince. So the Pilot drew a sheep, but the Little Prince rejected the first drawing, and the second drawing, and the third drawing. Finally the Pilot made a drawing of a box and said: "This is only his box. The sheep is inside" and the Little Prince was satisfied. (de Saint-Exupéry, 1971, p. 8)

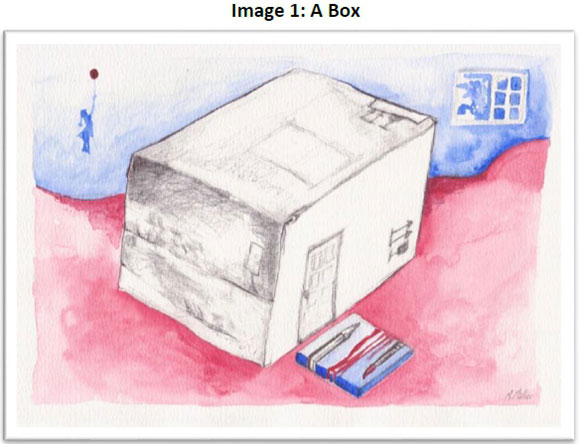

I have always loved the story of the little prince and have learned much from it. A few years ago, when I was working on my doctoral thesis (Müller, 2016), I decided to write a story about some of the experiences I had had in educational contexts, both as a student and as a teacher. I knew I wanted to follow a narrative, arts-based methodology, but I was unsure where to start with my narrative. So, I thought of the little prince and the box with the sheep inside. I remembered a box at the top of my cupboard where I kept a few sentimental objects I had collected over the years. I got the box down from its hiding place and made a drawing of it (Image 1).

Inside the box, are objects that will help me tell my story. The memory box itself is the first object to help me to tell my story. As I open it and take out the objects, the story starts to unravel. The story is a collaborative autobiographical narrative of educators in South Africa, and based on my doctoral thesis (Müller, 2016) in which I used objects to create portraits and collages of the participant narratives. This research process helped me make affective connections between the different narratives and to construct a story of educators working in the higher education space. The object narratives and collages that emerged from my research highlight the complexity of educator subjectivity in relation to social change. The use of objects made it possible to explore educator memory, experience, and subjectivity in a collaborative way. Memory is used to explore microsocial expressions as reflective of larger narratives of social change and transformation. Therefore, memory, as expressed through objects, should not be seen as a representation of a past reality but, rather, as an occurrence that is constructed in the present and entangled with identity and subjectivity. Educator subjectivity is used to explore the affective possibilities and entangled relationships of human and nonhuman others in order to venture beyond the fixed identity categories that often permeate social justice research. The objects I discuss in this article serve as embodiments of memory (Cole, 2011) and also as nonhuman participants through which educator subjectivity is explored. The objects help to create a narrative construction of educator subjectivity as assembled, decentred, and multiple (as opposed to fixed identity categories). Memory objects make it possible to visually navigate the complexities, the contradictions, and the constant shifting of our identities, and explore how these impact on our curriculum and our pedagogy. The aim in this article is to present a narrative that emerges from objects to create ways of thinking about the complexity, contradictions, and messiness of our experiences, memory, and subjectivity.

. . . are a pencil and a paintbrush,

The first object I take out of the box is a small terracotta tile (Image 2), which is painted and glazed. As I hold the tile in the palm of my hand, I remember a sunny, faraway day out in the green, grassy midlands of KwaZulu-Natal, where I was painting ceramics with my Grade 12 visual arts learners. It is a simple picture of a paintbrush and a pencil and a space in between them. As I unwrap this memory I see myself standing in the space between art and education, and it is from this space that I now write; the pencil writing the narrative and the paintbrush painting the picture. For me, the pencil is symbolic of the theoretical underpinnings of this story, while the paintbrush symbolises my methodology. The little tile becomes an entry point into a larger narrative in which I reflect on my experiences as a child, a student, a teacher, a lecturer, a mother, and so forth, and how these connect to the experiences of others. This object helps me to shape and narrate a memory and, from there, it helps me make connections to other memories and the memories of others to form an entangled memory web through which educator subjectivity can be read. The box is at the centre of my memory web, and branches out to many other memories such as the little terracotta tile. When tracing my hand over the smooth surface of the little tile, I enjoy looking at the colours, and the memory of making it is pleasant. In this memory, I am sitting around a table with my students and we are all working together in silence, each busy with their little artwork. Through discovering this art object years later, I discover a link between my experience, art, and educational research.

I used the box and the tile to start my narrative and, from there, continued to build the memory web by using more objects I had made-collages, drawings, and sculptures. Each object helped me see different connections: the connection between myself as a researcher, teacher, and artist; the connection between my present self and past self; the connection between educational theory and arts-based methodology, and so forth. The objects helped me to make a tactile, real-world connection to more abstract thoughts and feelings, which also helped me to narrate and organise my thoughts into a more coherent story. The objects helped me to express how theory and methodology become conflated in arts-based research, and helped me to explore the entanglements and connections between social change, identity, subjectivity, and educational contexts through the memories of educators working in the higher education space.

Each new object makes it possible to remember certain moments, feelings, emotions, and sensory experiences. Some objects connect me to early childhood memories and others, to more recent events. Some memories are crystal clear, while others are blurry. In fact, some of the memories I uncover do not even belong to me, but they all become part of what I refer to as a memory web. As I continued the work, I started to think of the memory web as a research assemblage (Deleuze & Guattari, 1988) that makes it possible to explore narratives of educator subjectivity and transformation in education. By positing the research assemblage as affective and transformative, I position my research as post-qualitative (St. Pierre, 2011), where the focus falls on doing different kinds of research. This approach is in line with poststructuralism, which suggests that agency is not a product of individual will but, rather, resides in "the conditions of possibility that provoke new thought" (Davies, 2010, p. 55). I am interested in how objects can help us understand educator subjectivity as assembled, decentred, and multiple, and how such an understanding creates the conditions of possibility to think differently about social change and education.

In thinking around issues of social justice and educator subjectivity, I used the theoretical framework of anti-oppressive education, which is informed by critical theory and looks at the way in which socially constructed identities influence equality in educational experiences. Kumashiro (2000, p. 5) argued:

whether working from a feminist, critical, multicultural, queer, or other perspectives, [researchers] seem to agree that oppression is a situation or dynamic in which certain ways of being (e.g., having certain identities) are privileged in society while others are marginalized.

Kumashiro (2000) also noted, however, that oppression can intersect and be multiple and situational. While critical theory is useful to name oppression and to become critically conscious, Kumashiro (2000, p. 25) argued that we "need to make more use of poststructural perspectives in order to address the multiplicity and situatedness of oppression and the complexities of teaching and learning." I used narrative inquiry to explore the multiplicity, the situatedness, and the complexities of experience. In this method of inquiry, it is useful to explore the autobiographical narratives of educators working towards change and transformation. Narrative inquiry in education is strongly influenced by an understanding that education, experience, and life are inextricably intertwined (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000, p. xxiii). Thus, in order to study education, one needs to study life-and how the lives of those involved in educational settings are filled with complexities, hopes, dreams, wishes, and intentions (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000, p. xxv). This makes it necessary to look beyond grand narratives and generalisations of change and transformation to the small micro-expressions of experience and memory that shape educator subjectivity. In this article, I look at how objects make it possible to tap into the micro-expressions and narrations of educators' being, belonging, and becoming. In working with educator identity, subjectivity, experience, narrative, and memory I hope to create conditions in which we can think about socially just education in new ways.

Working in a narrative tradition of inquiry means that narrative is both the phenomena we study and the method of study (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000). And, according to Clandinin and Connelly (2000, p. 4), "we [narrative researchers] see teaching and teaching knowledge as expressions of embodied individual and social stories, and we think narratively as we enter into research relationships with teachers, create field texts, and write storied accounts of educational lives." Within this frame of research, the researcher becomes part of the research story-how we live, have lived, and narrate our lives become central to who we are as educators. Our memories help us think simultaneously about the continuity of experience and about past, present, and future in the ever-changing social milieus we work in. Using objects to create a memory web with others might help us to make connections between our own experiences and the experiences of others.

In working with educator autobiography, Denzin (2008, p. 118) spoke of the use of memory as follows: "In bringing the past into the autobiographical present, I insert myself into the past and create the conditions for rewriting and hence re-experiencing it." Similarly, I explore educator memory through the use of objects, not as a representation of a past reality but, rather, as an "event" that is constructed in the present and entangled with identity and subjectivity. The memory event is used as an occurrence to explore microsocial expressions as reflective of larger narratives of social change and transformation.

I used arts-based research in pursuit of alternative forms of data representation to increase attention to complexity, feeling, and new ways of seeing (Cahnmann-Taylor & Siegesmund, 2017). The objects, thus, guided me in telling my own story and also in telling the stories of others. I pursued a collaborative methodology in which I invited other educators to share their experiential narratives to create a memory web through which we could read our collaborative narrative through an antioppressive lens. Davies and Gannon (2012, p. 362) explained that, in collective biography, we use memory stories to explore the entanglement of the self and others as conditions for new possibilities. For Mitchell, Strong-Wilson, Pithouse, and Allnutt (2011, p. 1),

the fundamental purpose of memory-work is to facilitate a heightened consciousness of how social forces and practices, such as gender, race and class, affect human experiences and understandings of how individuals and groups can take action in response to these social forces and practices in ways that can make a qualitative difference to the present and the future.

In my doctoral thesis (Müller, 2016), memory was collectively explored through objects to create a heightened consciousness of our individual and collaborative experiences of the transformative possibilities emerging in educational contexts. Through this work, I hope to explore how working with social justice in education can become more relevant, responsive, and authentic through the use of arts-based methodologies.

.. . a little white clay figurine,

So, my paintbrush is painting and my pencil is writing as I unpack the box. My thoughts unfold in a scattering of objects that cover the surface of the kitchen table, cluttering my space and threatening to push me out altogether. To the left, a tower of theory books is leaning at a dangerous angle. Behind the theoretical tower is a larger, solid mass of unmarked student essays. I turn my attention to the collection of children's books, with Where the Wild Things Are (Sendak, 1963) at the top, and open on the page where the walls become the world all around Max. To the right of the storybook, is a photo album from the mid-1980s, which is struggling to keep my childhood inside its yellowing pages. One picture has escaped-a faded image of a little girl holding a red balloon. The picture takes shape. The little girl steps out of the picture and into my memory as I use the white ceramic clay to shape a little figurine. I call her Daisy (Image 3).

Daisy is a little white girl. I created her to help tell my story. She grows up in the 80s in South Africa. She goes to a "good," well-resourced Afrikaans-medium school. All her classmates are white and Afrikaans. She goes to church every Sunday. Everyone at church is white and Afrikaans. Her world is white and Afrikaans. The only people of colour she sees and knows work as cleaners or gardeners. Although this is Daisy's story, it is not dissimilar to many other stories of white Afrikaner children growing up during the 80s in South Africa. As a little girl, she is naively unaware of the turmoil and unrest brewing outside of her suburban, middle-class life. She has never heard of the Struggle or, even, apartheid. In her life, things are just the way they are. Her education, Christian religion, and Afrikaner culture blend into one seamless unquestionable entity of school, church, and "nation," while her family enjoys the privileges of the white middle class during the 80s in South Africa. The adults, however, are whispering that change is coming. Her parents seem positive about the change, so she feels it must be a good thing. In some of her friends' homes, however, there seems to be more anxiety than positivity. She knows this because their parents store up canned food and seem to worry that something bad will happen. They hear the name of Nelson Mandela more and more often. She watches his release on TV without really comprehending what it is all about. The world on TV looks far removed from her reality. There is a referendum-Yes or No-and, eventually, an election. There is a new flag, a new president, and a new South Africa. One day, during 6th grade, the school principal calls the whole school to the hall to announce that the first girl of colour will come to their school the next day and that they must be kind to her. As Daisy grows up, she moves out of the isolated world of her childhood and into a changing and diverse world. By the time she becomes a teacher, many years later, the ideals of a rainbow nation are a distant memory for most. Her experiences inside and outside the classroom are complex, difficult, and challenging. She feels confronted by her own whiteness in the transforming educational space. It is as if the image of that little white girl now starts to haunt her.

As I write Daisy's story, I have hooks (2003, p. 26) in the back of my mind:

I have found that confronting racial biases, and more Important, white-supremacist thinking, usually requires that all of us take a critical look at what we learned early in life about the nature of race. Those initial imprints seem to over determine attitudes about race.

And so, I start the story of Daisy at a point in her early life. I use the art object to open up my memories of growing up in a time of drastic societal change. The object becomes part of my memory web of experiences through which I explore my own subjectivity. The process of exploration also makes me aware that my box is rather small, limiting, partial, and incomplete. I realise that I need to extend the memory web to make connections to the memories of others. This realisation led me to follow a more collaborative and participatory process of storytelling for my doctoral research on anti-oppressive education, educator identity, and social change.

In writing my doctoral thesis (Müller, 2016), I created portraits of educators working towards antioppressive education. The portraits took the form of visual-textual collages. I did not specifically set out to use objects as part of the creative process, but given that I was using an arts-based methodology, I wanted to work with art as a source of data collection and data interpretation. Therefore, I gave the participants some art materials and asked them to create an art object of their choice (drawing, sculpture, collage, etc.), which would help them tell their story. I also asked the participants to bring something to an interview to initiate the conversation, and elicit memories about experiences with change and oppression in educational contexts. Some participants created clay objects or brought drawings and photographs and used these to share some of their memories and experiences with me. In the next phase of the research, I used the data gathered through these interviews to create collages based on the transcripts of the narratives participants shared, and visual representations of the objects they brought to the conversation. After creating the collages, I shared them with the participants and asked them to help me read and understand their stories so that we could collaboratively explore the textual and visual narratives that emerged. The collages, thus, helped me move beyond my "box," and beyond my own memories to look at the memories of those around me. In using objects to build this collaborative memory web, we were able to explore our diverse experiences. The use of objects made it possible to move us towards new understandings around social change and social justice in education.

. . . a mirror and a birth certificate,

One of the participants, Alice (all participant names are pseudonyms), chose not to create or draw anything with the art materials I provided but, instead, narrated her story to me and asked me to make the drawing. I listened to her narration and visualised some parts of it by creating drawings of some of the objects she mentioned. These were later incorporated into my drawing (Image 4).

One of the central objects in Alice's narrative was a mirror:

I'm afraid I'm stuck In this mirror. The thing Is, I'm not sure if I practice what I preach. So, like, I feel all this sense of uncertainty and I'm, like, looking at myself and I'm wondering, "Am I doing the right thing?". . . For me, teaching is like a kind of mirror and looking into this and whatever's going on in the classroom is reflecting . . . back on me. So in a way I am stuck in the mirror, you see? (Müller, 2016, p. 109)

A second object that emerged from Alice's story was a birth certificate:

I was in Grade 7. Those were the days of apartheid and that school was an Indian school. I didn't look typical . . . like a typical Indian, you know? And I had this kind of accent that was not Indian, and I felt different and I was made to feel different, because I came from this different kind of school . . . because before that I had been in a Catholic school; it was a private school, so we were all mixed-whites, blacks, coloureds, Indians. I remember it as a strict and rigid kind of schooling: rote learning and questioning, and obedience, discipline, and respect for elders. There was this distance between the teachers and us, and the majority of the teachers were Catholic nuns. So anyway, there was this otherworldly kind of disciplinarian, you know, so they always threatened you with Jesus and God when you did anything wrong, and they were a bit abusive. Yes, they were physically abusive . . . they used to give us these German knocks, like knuckles on the forehead . . . And even if your parents sent you, like, little boxes of sweets and stuff, that was even . . . they would check what was in it and then they would make decisions about what they would give you and when they would give it to you . . . so it was . . . but I learned discipline there, and to work hard . . . and I learned to be independent. But anyway, then that school closed down and on my first day at this new school, this Indian school, in the afternoon, the principal wanted to see me, and she asked, "What are you? What is your race?" And I was not sure... so she said, "Are you coloured?" And I was, like, so uncertain about what I was . .. I said, "Yes, I'm coloured." So she called my mother that day and she asked for my birth certificate.

I felt very ostracised in that new school. But I did very well and I outperformed everybody else in class and stuff like that. But I was always a rebel. I always wanted to . . . I had difficulty in conforming there in that school . . . I had very curly hair, you know? Once, I was pulled out in assembly and they told me I'm not allowed to have a perm . . . and my mother had to take me to the hairdresser to ask them to try and straighten it, but then they were saying that, "She's so young; why must she if this is her natural hair?" Uhm, but schooling, ja, was . . . after a while . . . you know, apartheid was so deeply entrenched that we never really questioned its effects on us. So we conformed, we did what we had to do, 'cause if we didn't then we were punished in some-not physical punishment-but in some form, in some way, you were punished and then ostracised or your name was read out in assembly or something... being a good student meant to conform. (Müller, 2016, p. 110)

Alice helps me to add two objects to the memory web: the mirror and the birth certificate. As educators, we are always stuck in a mirror. What we do reflects back on us. We cannot separate our identities from our classrooms, our pedagogies, or even the curriculum. As Jansen (2017, p. 169) reminded us: "Teachers interpret the curriculum to students on the basis of their own experiences, backgrounds, politics, and preferences." Many of us who now work in higher or basic education grew up in apartheid South Africa. Our experiences of education were shaped in racially separate spaces, yet now we are teaching in racially integrated and transforming spaces. However, the memories of the past are still present in our classrooms. The apartheid legacy of categorisation of race and other parts of our identities still limits our interactions, to some extent. In Alice's narrative, the objects thus highlight the very powerful effect of past experience on educator subjectivity. From her story, I learn that work towards social justice and social change in education must leave room for the past experiences of the educators to emerge into the present-not to keep us stuck in the past but as a potentiality that helps us move beyond our history towards a new way of being in the present. Sharing these past experiences with our students and colleagues might be important to form honest relationships in which we interrogate how we came to where we are now so that we can move forward together. In the next story, I further explore how past memories can influence the educator's being in the present.

. . . a car and a bed,

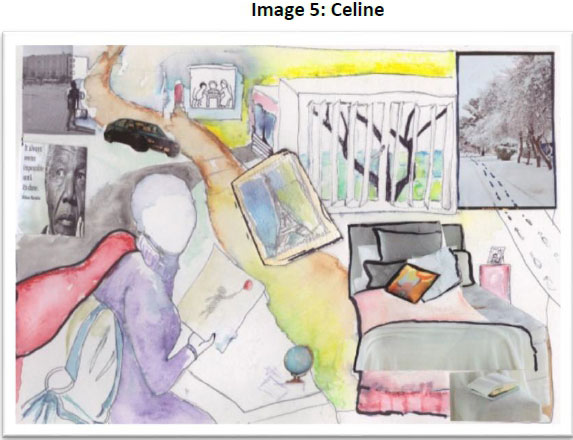

Celine brought a number of photographs to the interview and used these to narrate the story of her life and make connections to her current experiences. I also used some of the objects that emerged from her narrative to create a collage after my interview with her (Image 5).

One of Celine's objects was a car:

If you drive a car, then they think you have lots of money. There's never a time when I visit my family, or my relatives, and not one person didn't ask for money. I grew up in these dusty streets . . . But now my situation has changed. I think that I learned from my mother's experiences-don't live from month to month, because that's what we were doing, you know, we were living from month to month. But I just refused to . . . it was not a very nice life, so I just refused to live like that, you understand? I just said to myself, "I will not." You know, by the 25th you have stress of what're you going to eat or don't even have R50; I just don't want to live like that. So, finances have played a very huge role, and things are better now. Things are much better, but family expects a lot-not my mother, but the extended family-they expect so much from you. When you come they will tell you, "I don't have sugar, I don't have tea, I don't have this, and I don't have that." And I always ask them, "But why don't you have it?" Because honestly, when they see me, they see an ATM machine.

Growing up we struggled like . . . any other house, because that was normal. Sometimes you would ask for things, but you wouldn't get It, not because Mommy didn't want to, but simply there was no money . . . and going to school you're immediately confronted with things that you were really not aware of. Where you get kids at school that would carry very nice lunchboxes, and then when it's school concerts and things like that, both parents come, and my mother cannot even come for that.

In my entire family with all my siblings and my cousins, I was the first one to finish matric. Both of my grandparents didn't go to school, so getting higher education ... I was the first one. It was sort of a motivator to say, "I'm the first one to . .. I'm the first one not to have kids, I'm the first one to go to university, all the good things I'm going to be the first." So that was, it was a challenge that I gave to myself to say that this is what I want to do, and I know that I am going to do something great with my life. (Müller, 2016, p. 115)

Another object that I used in Celine's collage was a bed. Celine spoke about her memory of buying the bed with so much joy and enthusiasm that it became a strong visual element in her narrative:

In my final year, I applied and got an internship at the university. So now I was sorted, not only taking care of myself, but also taking care of my younger sister. So that was nice, and then, you know, I could see things developing, slowly but surely, you know, things were becoming ok. So, at least once in a while I could also buy my sister some nice shoes, 'cause I wanted her to look much better than I did, you know, at least so that she could fit in. I don't know if that makes sense, but, you know, at least she didn't struggle as much as I did when I was still an undergraduate.

I remember leaving work early on the day I got my first paycheck. I went to buy myself a nice bed . . . I went to buy new pillows . . . new everything. And it was on a Friday and I remember it was cold on that day. The first thing I bought was a comfortable bed. As a student, I had the most uncomfortable bed, and I shared it with my sister. I don't know how old it was, it was a very small bed, and I just asked my mother, "Can you please just buy us two separate beds-single beds?" She said, "I'm not going to do that; if I do that, you guys are going to get so comfortable you will sleep and you won't study. So, with this uncomfortable one, when you think of sleeping, you'd rather sit and study." (Müller, 2016, p. 117)

Celine's narrative speaks of her experiences with having, not having, and wanting material things- how she was envious of the other children at school who had nice lunchboxes, how she desired a comfortable bed, and how all of this motivated her to study. It also speaks of her present experiences of having, and how others expect her to pay back. In her narrative, she speaks of the effects of socioeconomic changes and also about the fluidity of identity. Her identity changes as her socioeconomic circumstances change, and yet the memories of past experiences are part of the present. In this way, her narrative connects to Alice's narrative of being stuck in a mirror or needing a birth certificate to prove your identity. It also connects to the narrative of Daisy, who grew up having material things but now works in educational settings with colleagues and students who had dissimilar experiences. Thus, the objects that emerge in the arts-based narratives make it possible to explore the relationship between identity and material things-having a bed, or having a car, and so forth. Classed, gendered, and racial identities all emerge as part of the educator's subjectivity. In working towards social change in higher education, we need to interrogate how the educator acknowledges and engages with issues such as of class, gender, and race, and use these to productively imagine new ways of being different in the higher education context. In other words, Celine's narrative shows how we navigate the fluidity of our identity as it changes over time, and we become different. In the next narrative, Mick uses a photograph to express his experiences with difference, otherness, and of being othered.

. . . a clown, a cliff, and a photograph from Thailand,

Mick was one of the participants who used the art materials to create an art object to tell his story. He made a drawing of a clown juggling to represent himself.

He said he felt like he had to juggle so many things as an educator. He also brought a picture of a man leaping across a cliff to the interview, and a photograph of himself with some students in Thailand. I used these objects to create a collage for Mick (Image 6):

Last week in class, it was the students that brought up the topic and we ended up talking about race and then students got angry . . . And then a whole group of white students said, like, they are so tired of this whole race thing and everything, and the black students kept quiet in the classroom, and then you could just pick up the tension. And I was standing there in the front and I was teaching them, and I thought, "What did I do here?" And so, when I noticed what was going on, I told the students, "Ok, just take a minute to think about what happened in the last five seconds in this classroom; just process it and make sense of what happened." And then I asked them to speak to their group members, and then I asked them to give me feedback, and there was this backlash about how this is terrible that we keep talking about this race thing and . . . So I walked out of that classroom feeling extremely confused, frustrated, and I was questioning, "Did I do more harm than anything about healing in that classroom? Will these students come back next week? What happened here?"

What made those students get so frustrated, so angry? Because they were angry. What made them feel so guilty? They felt like I was calling them racist; they felt like I was telling them they're bad people; they felt like I was categorising them as everyone who is bad in society. It is like I'm trying to make them leap across a cliff, you know? They have to leap and they might get hurt and they don't even know what is on the other side of familiar. The familiar side is where students are comfortable, everything is normal and they know everything and nobody is rocking the boat. And I think when we started to talk about the issue of race and we didn't move away from it, it was like now I made them to be in that space, that dangerous space where there is nothing and I actually pushed them to a foreign place. So, it's like going to another planet and someone just drops you off there. 'Cause suddenly they were hearing different perspectives; black students were talking about their experiences and it was, like, "Now, what's happening?" And the black students were also hearing the perspective from the white students, so they were in a very foreign space.

This is a picture we took when we were in Thailand with my students, and my student took this photo, and we visited this village . . . then we got to meet these kids who were playing there. I used it as my Facebook, and someone commented on how the one child is just staring at me, just looking at me with these eyes, which I didn't really notice at first. In a sense, it represented the experience of being in Thailand, where I was . . . we were the other; my students and I represented diversity in a different way. So, being black, we were the only black people, four of us, so this was very common for people to stare at us like this . . . Or to want to touch us . . . Not so often, but there was that curiosity to want to be near us . . . Like, at KFC, it was the same; I think people stopped eating and it was weird, because for them it didn't seem like it was rude . . . it was just, like, really, staring at these different. .. (Müller, 2016, p. 129)

In Mick's narrative, the objects help us to move from his past memories into present contexts. The picture of the clown helps to express the difficulty of working in a transforming and changing society. In our work in education, we are always juggling multiple roles, identities, and memories. We try to guide students to different understandings. We take them to the cliff and ask them to leap, but as we do that we doubt ourselves, or whether we are doing the "right" thing. In Mick's narrative, we see how social justice work is not about certainty and knowing; it is about uncertainty and self-doubt. The objects help to communicate his discomfort, frustration, and confusion. He talks about how this kind of work makes you feel like you are in a foreign space, and how the students also feel like that. He uses his experience in Thailand to explain the feeling of being othered, of being stared at in a foreign space. In this way, he connects his experience of being othered to the previous narratives of Daisy, Alice, and Celine, which all have some expression of guilt, fear, anger, blame, and shame. As educators working in a rapidly changing higher educational context, we often struggle with difficult and complex emotions and self-doubt. In order to move with our students, we need to become different when we engage with social justice work. When we advocate for change, we need to interrogate our memories, experiences and form new collectivities and new subjectivities that allow us jump to the other side of the cliff, or move away from being stuck in the mirror.

. . . and a (partial) picture of (multiple) identities and (complex) change in education.

A drop of purple paint falls on the nearly perfect picture of an apple tree next to a crooked house. Little eyes shoot full of tears. A six-year-old Daisy becomes aware of the teacher's hand on her shoulder, as the teacher takes the brush and puts two wings on the purple splatter. "What a lovely purple bird," the teacher says, and Daisy's tears dissolve in a proud smile. (Müller, 2016, p. 200)

I find my childhood picture (Image 7) at the bottom of the box, and realise what this memory object makes possible: it helps me understand that we have to look past the utopia or desired perfect state to accept and appreciate the flaws, and understand how our mistakes and imperfections can "change the picture"-rather than reproduce a "flawless" sameness. That drop of purple paint does not make the picture better, but different. Kumashiro (2000, p. 46) summed this up beautifully:

Although we do not want to be the same, we also do not want to be better (since any Utopian vision would simply be a different and foretold way to be, and thus, a different way to be stuck in a refined sameness); rather, we want to constantly become, we want difference, change, newness. And this change cannot come if we close off the space-between.

As South African educators, we work in in-between spaces, where we are troubled by our identities, memories, and experiences. Our engagements with anti-oppressive education and social change are often painful, messy, and uncomfortable. I know this because for the last few years, I have taught social justice modules in undergraduate and postgraduate programmes at the University of the Free State. Cocreating the narratives with participants for my doctoral study helped me to also recognise that my experiences were shared by other educators, regardless of our very diverse backgrounds and social identities. It also made me aware of the different challenges my colleagues face, and have faced, and how I can learn from them.

At times, I have felt stuck in a mirror (like Alice) and felt that everything in the classroom reflects back on me. I have felt haunted by my social identity as a white South African and uncomfortable about my white privilege. Through the collaborative arts-based narrative, I learned that working towards social justice and social change in education must leave room for our past experiences to emerge in the present-not as a way to keep us stuck, but as a potentiality that helps us move beyond our fixed identity categories towards a new way of being in the present. I also learned that affective responses are useful in working towards social change and transformation. For example, in response to Celine's narrative, I felt guilty because, unlike many of my students and colleagues, I have always had the material realities of a nice lunchbox, a car, and a comfortable bed. hooks (2003, p. 119) reminded us how important it is to deal with the past if we wish to become different:

Some people believe that it is best to put the past behind you, to never speak about the events that have happened which have hurt or wounded us, and this is their way of coping-but coping is not healing. By confronting the past without shame, we are free of its hold on us.

To confront my past experiences and guilt was a good way to move away from a passivity towards a more productive focus, and ask the question: "How do I bear responsibility for the injustices in my community and in the world?" (Zembylas, 2018, p. 12). In this way, I found the collaborative inquiry useful to confront my own past and privilege, and to imagine myself as part of a different collectivity. Furthermore, the collaboration with colleagues on these narratives helped me find ways to move to a new understanding of subjectivity in which I become more than the sum of my essentialsed parts. Becoming different is a central, and sometimes painful (hooks, 1994, p. 42) part of social justice work and the difficulty of this is highlighted by Mick who described how he struggles to make students jump over a cliff, and also struggles to take the leap himself. That leap we have to make as we work towards social change and transformation implies that we need to seek new subjectivities as we leave our former selves behind. This is in line with Kumashiro's (2000) anti-oppressive theory, which tells us to always look beyond what we know as we work to become different.

Using objects to construct a narrative of educator subjectivity is a way to think about the connections between lives, memory, experience, and affect in relation to anti-oppressive theory and change in education. This type of narrative is intended to help us cross our differences to engage in conversations about oppression and think about new ways of being. I, therefore, approach anti-oppressive education as a process that requires partial and imperfect knowledge, which can only be explored collaboratively. In this collaboration, the use of objects helped us to find and express the entanglements and connections between our surroundings, experiences, and theoretical understandings of social justice and anti-oppressive education. The memory web and collaborative narrative that emerged made it possible to explore the multiplicity, complexity, and affective dimensions of educator subjectivity in the context of transformation social change.

References

Cahnmann-Taylor, M., & Siegesmund, R. (2017). Arts-based research in education: Foundations for practice. New York, USA: Routledge. [ Links ]

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, USA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Cole, A. L. (2011). Object-memory, embodiment, and teacher formation. In C. Mitchell, T. Strong-Wilson, K. Pithouse, & S. Allnutt (Eds.), Memory and pedagogy (pp. 223-238). New York, USA: Routledge. [ Links ]

Davies, B. (2010). The struggle between the individualised subject of phenomenology and the multiplicities of the poststructuralist: The problem of agency. Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, 1(1), 54-68. [ Links ]

Davies, B., & Gannon, S. (2012). Collective biography and the entangled enlivening of being. International Review of Qualitative Research, 5(4), 357-376. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1988). A thousand plateaus. London, UK: Athlone. [ Links ]

Denzin, N. K. (2008). Interpretive biography. In J. G. Knowles & A. L. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, and issues (pp. 117-125). Los Angeles, UK: SAGE. [ Links ]

de Saint-Exupéry, A. (1971). The little prince (K. Woods, Trans.). New York, USA: Harcourt Brace & World. (Original work published 1943) [ Links ]

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York, USA: Routledge. [ Links ]

hooks, b. (2003). Teaching community: A pedagogy of hope. New York, USA: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jansen, J. D. (2017). As by fire: The end of the South African university. Cape Town, South Africa: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Kumashiro, K. K. (2000). Toward a theory of anti-oppressive education. Review of Educational Research, 70(1), 25-53. [ Links ]

Mitchell, C., Strong-Wilson, T., Pithouse, K., & Allnutt, S. (2011). Memory and pedagogy. New York, USA: Routledge. [ Links ]

Müller, M. (2016). A collaborative self-study of educators working towards anti-oppressive practice in higher education (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of the Free State, South Africa. [ Links ]

Sendak, M. (1963). Where the wild things are. London, UK: Random House. [ Links ]

St. Pierre, E. A. (2011). Post qualitative research: The critique and the coming after. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (pp. 611-626). Thousand Oaks, USA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Zembylas, M. (2018). Encouraging shared responsibility without invoking collective guilt: Exploring pedagogical responses to portrayals of suffering and injustice in the classroom. Pedagogy, Culture & Society. doi:10.1080/14681366.2018.1502206

1 Ethical clearance number: UFS-025546