Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Educational Research for Social Change

On-line version ISSN 2221-4070

Educ. res. soc. change vol.6 n.2 Port Elizabeth Sep. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2017/v6i2a3

ARTICLES

Espoused and enacted values of student teachers interrogating race, class, and gender in literary texts

Ansurie PillayI; Johan WassermannII

IUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal Pillaya3@ukzn.ac.za

IIUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal wassermannj@ukzn.ac.za

ABSTRACT

While South Africa has embraced a democratic ideal for over 20 years, the dynamics of race, class, and gender have not been fully engaged with. In an educational setting, such as a university lecture room, active interrogation of these and other issues may present opportunities for understanding and change. In this article, the authors present findings from a participatory action research study that used literary texts as catalysts to interrogate issues of race, class, and gender. The study was underpinned by critical pedagogy and asserted an empowerment and transformation agenda. Using qualitatively analysed data from observations, interviews, focus groups, and written tasks, the authors found that while the student teachers in a teacher education programme espoused certain values related to characters, events, and issues in the literary texts studied, what they said they do in their daily lives proved contradictory. However, as the six cycles of the study proceeded, awareness of the complexities of the student teachers' lives and the contradictions inherent in their behaviours enabled the student teachers to interrogate issues of race, class, and gender from an informed position, and helped engender their journeys towards empowerment and transformation.

Keywords: race, class, gender, espousal, enactment, literature

Introduction

In this article, we examine the discrepancy between what student teachers in a South African university lecture room say, and what they do when working with issues relating to race, class, and gender in literary texts. The student teachers, studying to become teachers of English at primary or high schools, worked with the primary author and lecturer-researcher as participants and coresearchers in a 2-year participatory action research (PAR) study. The aim of the study was to use literary texts as catalysts to enable the student teachers' empowerment as agents of change in their future classrooms. We worked on the assumption that teachers who want to be agents of change should be committed to improving and making a difference to their own lives and those of their students, and have a moral purpose, democratic principles, and a clear vision of why they are teachers (Biesta & Tedder, 2006).

While the study generated many findings, this article only considers the unanticipated data that emerged, highlighting the discrepancy between how the student teachers engaged with concepts of race, class, and gender in the literary texts and how they said they lived the ideas in their everyday lives. The discussion of findings will explain this discrepancy with the data to support it.

The literary texts studied were two novels, two plays, and two films. The novel The Madonna of Excelsior by Zakes Mda (2002) is based on the real-life events surrounding the arrest of 19 citizens in 1971 rural Free State, South Africa, under the Immorality Act (1950), which forbade sexual relations between people of different races. The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy (1997) is a novel set in Kerala, India, and tells of the childhood experiences of a set of twins who bear the brunt of those who do not follow society's rules. The play Sophiatown by The Junction Avenue Theatre Company (1988) is a South African play that tells of forced removals in apartheid South Africa (see Native Resettlement Act of 1954) and the vibrancy and violence of a community that tries, in vain, to resist removal. The Tempest by William Shakespeare (1623/1913) is a play of magic, illusion, and usurpation of power, and the ramifications of each. The film, The Colour of Paradise, directed by Majid Majidi (Ghaemnaghami, Karimi, Mahabidi, & Sarab, 1999) tells the story of a young Iranian boy who is physically blind, yet unhindered, and his father who is blind to the many possibilities in his life. The film, Much Ado about Nothing directed by Kenneth Branagh (Branagh, Evans, & Parfitt, 1993), is based on William Shakespeare's play of the same name (circa 1623), and tells the story of love returned and unrequited, and the trickery involved in both. All the texts were prescribed prior to the lecturer-researcher joining the university and, thus, texts were not specifically chosen for the study.

Throughout the study, the student teachers focussed on race, class, and gender, among other issues that emerged from the texts, and considered how they would create awareness of these issues in their English classrooms. Throughout the study, we acknowledged the intersectional nature of race, class, and gender, and recognised that social identities comprise such intersections (Crenshaw, 1991), which are socially constructed and built on differences and positionings of groups (Brewer, 1999; Ken, 2010). We understood that the meanings of race, class, and gender are localised and depend on and mutually constitute each other, and thus no individuals are all oppressed or all oppressing (Ken, 2010). However, for the purposes of this article, each concept has been teased out individually by reading its impact within the literary texts studied.

Race, class, and gender feature prominently in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (1996) that seeks to build a society where opportunity is not defined by race, gender, and class and all citizens of the country are ensured the right to human dignity and freedom from discrimination of any kind. This is unlike the previous apartheid Constitutions (1961, 1983), which limited opportunities racially.

The curriculum and assessment policy statements (CAPS) for home language (Department of Basic Education, DBE, 2011a) and the CAPS for first additional language (known as second language internationally, DBE, 2011b), which guide the teaching of English in schools in South Africa, are created from the social justice agenda of the Constitution (1996) and outline the need for critical approaches to teaching and learning. Human rights and social justice issues, including those involving race, class, and gender, underpin these CAPS documents. The rationale for the study is thus shaped by the requirements of the CAPS documents, which indicate that teachers need to engage with issues of race, class, and gender in the literary texts that they teach. The CAPS documents for home language and first additional language (DBE, 2011a, 2011b) instruct teachers to enable their learners to engage critically with literary texts by recognising and challenging perspectives, values, and power relations in texts and by engaging with the issues of race, class, and gender, among others. According to these CAPS documents, teachers may examine literary texts to ascertain how they are constructed and how the language forms, including those involving race, gender, and class, are represented. Teachers also need to teach learners concepts and competencies of diversity, democracy, and responsible citizenship, among others, to understand and respond to human and social dilemmas. By focusing on such issues in texts, learners are provided with opportunities to think critically and understand how some, or all, of these issues play out in their lives. This study, focussing on these social justice issues, therefore becomes important in a postapartheid South Africa as it attempts to develop and deepen the new democracy.

In this study, the texts were used to enable the student teachers' active engagement with, and evaluation of, literary characters' words and actions regarding issues of race, class, and gender. During the analyses of the texts, many of the student teachers' understandings and enactments of the concepts in their daily lives were revealed. It is this discrepancy between what student teachers say when working with literary texts, and what they say they do in their daily lives, that is the focus of this article. The article also highlights how the student teachers and lecturer-researcher reflected on the discrepancies, and the decisions taken to address them.

Literature exists to prove that what people say is often a poor predictor of what they do (Jerolmack & Khan, 2014a), and the espousal of values does not always translate into practice (Rusch, 2004). Research has also found that the attitudes of people are poor predictors of their behaviour (Ross & Nisbett, 1991), and there is often a discrepancy between people's intentions and their actions (Ajzen, Brown, & Carvajal, 2004). In addition, not all people understand and interpret issues in the same way (Jerolmack & Khan, 2014b). In this article, however, we argue that despite possible discrepancies in student teachers' understandings of these issues, and despite the differences in their espoused and enacted values regarding race, class, and gender, it is important to interrogate these issues in lecture rooms to start the process of critical reflection prior to student teachers teaching in their own classrooms.

Theoretical Framework

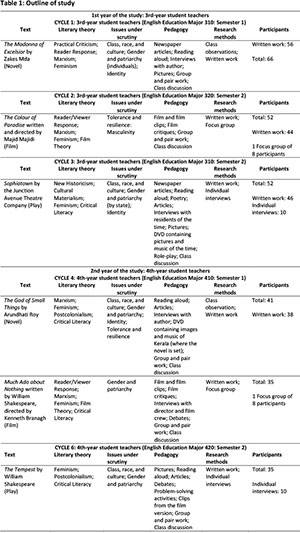

To enable a critical engagement with issues in the literary texts, the study, while using a variety of literary theories to engage with the texts (as seen in Table 1 below), used critical pedagogy as its primary theory. Critical pedagogy comprises a set of diverse principles founded on the possibility of transformation, and has a critical nature and liberating function (Darder, Baltodane, & Torres, 2009). This theory posits that education should commit itself to transformation towards justice and democracy (Giroux, 2009) and, being underpinned by a transformation and empowerment agenda, proved suitable for the study, which aimed to enable the student teachers' empowerment as they moved towards their own change agency. There is no set method for the implementation of critical pedagogy, which posits that education should be understood in its sociohistorical and political context (Giroux, 2009), making imperative an understanding of who the student teachers are and what their educational and other experiences comprise. Critical pedagogy suggests that the educational context should produce new knowledge through active engagement and dialogue, where knowledge is grounded in the experiences of students and lecturers, and where learning and education are culturally relevant, socially empowering, and participant driven (Giroux, 2009). This study, using literary texts to interrogate issues of race, class, and gender, actively engaged the student teachers through interactive pedagogies (see Table 1 below) in its quest to achieve its aims.

Using literary texts to interrogate social justice issues.

Researchers have identified that literary texts may enable an examination of the values and societal forces allied with society at large and social justice in particular (Comber, 2001; Kuo, 2005). Scholars such as Henning (1993) and Savvidou (2004) have recognised the value of using literary texts to prepare students for life through the unique opportunity it affords for grappling with the contradictions and struggles faced by societies, communities, and cultures. In addition, Sumara (1998) found that as students identify with, and interpret the experiences of characters in texts, they learn to reidentify and reinterpret themselves. Reading literary texts then becomes a site for thinking about their evolving identities, and, as Schachter and Galili-Schachter (2012) found, it heightens the possibility to initiate students' reflections on their own and other peoples' identities.

From a critical perspective, all teachers concerned with issues of social justice should provide time and space for analysis to facilitate students' questioning and unpacking of worlds presented in literary texts, in order to reveal their ideological and hegemonic discourses (Darder et al., 2009). Overall, literary texts are able to capture realities of concepts such as race, class, and gender in a way that theoretical discussions of the same concepts may not accomplish (Krog, 2012). It thus becomes important to engage student teachers in a critical pedagogy for social justice to enable their growth as agents of change. The concepts of race, class, and gender are unpacked in the Discussion of Findings section below.

Teacher education programmes that focus on social justice issues.

While teacher education programmes usually focus on some aspects of multicultural education, issues of racism, classism, and sexism, among others, are rarely dealt with in depth (Ladson-Billings, 2009). There are, however, teacher education programmes, located mostly in the United States of America, using a critical orientation, that encourage student teachers to teach against the grain (Carroll, Featherstone, Featherstone, Feiman-Nemser, & Rooseveldt, 2007; Cochran-Smith, 1991; Gopinathan, Tan, & Chao, 2008; Miller, Williamson, & Bolf-Believeau, 2011). Studies by Zeichner (1993), Ladson-Billings (1999), and Lane, Lacefield-Parachini, and Isken (2003) worked with issues of race, class, and gender in American teacher education contexts. Zeichner worked with student teachers to examine actions that challenged and supported oppressions and injustices related to class, race, gender, sexual preference, and religion. Ladson-Billings developed pedagogic options for student teachers to disrupt racist classroom practices and inequalities, and the study by Lane et al. (2003) built on a previous study by Cochran-Smith (1991) where student teachers were taught how to examine and confront prejudices of their own, other teachers, and their schools. These studies found that teacher education programmes should aim to produce "critical educators, community activists, organic individuals" who advocate for social justice (McLaren & Baltodano, 2000, p. 57).

In the South African context, there have been studies that have explored if, and how, social justice issues are considered in the teacher education context. Hemson (2006), in his study of three teacher education programmes, found that only one programme engaged systematically with social justice issues within the curriculum. In contrast, Robinson and Zinn (2007), working with three teacher education programmes preparing student teachers for primary school teaching, found that all the programmes had positive initiatives in place. However, these initiatives appeared to lack coherence. Other studies found that while teacher education programmes need to first disrupt issues of privilege before engaging with social justice issues, the student teachers in these programmes found them theoretical with limited practical application (Francis & Le Roux, 2011)-and preparation of student teachers, while aiming for a social justice agenda, often needs to give way to engagement with learning how to deal with and prepare for the realities of a South African classroom (Sayed, Badroodien, Salmon, & McDonald, 2016).

Methodology

This study used a participatory action research (PAR) design process, conducted over six cycles, where the lecturer-researcher (and primary author) worked collaboratively with the student teachers to try to achieve the aim of the study. PAR is a participatory, democratic process where knowledge is socially created, research is set in a system of values that encourages human interaction, and the research confronts practices that require change (Reason & Bradbury, 2006). It has both action and research outcomes, aims to be responsive to the emerging needs of a situation, and the results of action research should lead to improved actions in a specific situation (Boog, 2003). PAR can thus involve a spiral of cycles of research, experiential learning, and action (Boog, 2003).

Prior to the study, ethical clearance was sought from the university where the study was located and the study received full approval (Protocol Reference Number: HSS/0565/011D), and relevant gatekeeper permission was sought and permission was granted to conduct the research in the school with the English Education students. Once permission was granted, all the student teachers taking the English Education 310 module (the third of six modules in the English Education specialisation of the Bachelor of Education degree) were approached to participate in the study. The aims of the study were unpacked with them, all questions were answered, information sheets and consent forms were presented to them, and they were given time to consider whether they wanted to participate or not.

All students indicated a positive response to the study and, while they understood that the study would continue over 2 years, they were not obliged to remain within the study for the full duration of six cycles. I was aware that not all the student teachers taking the module would continue with subsequent modules because some student teachers take modules as electives and some do not need to take the 4th-year modules, as per the specific requirements of their degree. Thus, while the cycles built on each other, they also had to be individually self-contained.

While the student teachers committed themselves to the aims of the study, they were assured that participation was voluntary, anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed, and they had the option to leave the study at any time with no consequences to themselves. If they chose to leave the study, they would not be asked to provide data, and if they missed a lecture, the consequences were the same as missing any other lecture-they would need to find out what they missed and make up the required tasks. While the option to leave at any time was available to the student teachers, none of them chose to leave. While the English Education 310 lecture room served as the primary site of the study, written work, individual interviews, and focus groups occurred outside lecture times.

Racially, the entire class of 66 participating student teachers' profiles indicate (from their classification of themselves on university registration forms) that just over half of them (52%) classified themselves as Indian, 36% as African, 8% as white, 3% as coloured, 1% as other (racial categories are still in place at South African universities, presumably to redress past inequities). In terms of language, 63% considered English as their home language with 37% speaking an African language at home. Most of the student teachers were in their early twenties with just over 10% of the group being in their thirties; the majority (80%) classified themselves as female. The numbers in the class dropped as the study progressed over the 2 years due to some student teachers taking the modules as electives and because some did not need these 4th-year modules for their degree, as reflected in Table 1 below.

Table 1 explains the format of the entire study and includes the texts, literary theories, issues under scrutiny, pedagogy, and research methods of each cycle.

Each cycle comprised an intervention designed collaboratively with the student teachers and, within each cycle, the intervention was implemented and reflected on before further action. Interventions used the literary text as a catalyst to engage with issues of race, class, and gender. After each cycle, qualitative data collection strategies (observations, focus groups, interviews, and written work) were used to explore experiences and evaluate the interventions. While written work was collected after every cycle, observations were carried out in Cycles 1 and 4, interviews were conducted after Cycles 2 and 5, and focus groups were engaged with after Cycles 3 and 6.

The study used purposive sampling, which involves the researcher specifying the characteristics of the population of interest and locating individuals who match those characteristics (Patton, 2002). In this study, I, as lecturer-researcher, used total population sampling, a form of purposive sampling that works with the entire population, usually small, that has a specific characteristic (Patton, 2002). In the lecture room, the inclusion criterion was that they needed to be student teachers taking the English Education 310 module. For observations and written work, total population sampling was used to attain deep insight into the issues under study; this form of sampling is often used in participatory studies (Patton, 2002). For individual interviews with 10 student teachers, and focus groups comprising eight student teachers, a smaller purposive sample was chosen to achieve representativeness of the demographics of the total population in the lecture room. I purposively chose students to represent the race and gender of the student teachers in the lecture room because these two issues were foregrounded in the study. Working with these smaller numbers for interviews and focus groups enabled an in-depth study of the issues being discussed.

All data was thematically analysed qualitatively by immersion in the details and specifics of the data to understand the student teachers' multiple perspectives and viewpoints (Patton, 2002). For each of the six cycles, different groups of student teachers assisted with the data analysis. After each cycle, the student teachers were asked to volunteer to assist with the data analysis, and they could only volunteer once to allow for greater student teacher participation. They were taught how to code data from the different data sources, organise data into themes and patterns, and then find possible explanations for how and why such findings occurred. The analysed data served to determine what the next intervention should be. As the lecturer-researcher, I was aware of my power as their lecturer and assessor and thus had to reflect on, remind myself of, and confirm the aim of the research through ongoing reflection individually and as a group, and ensure that all actions were in the interests of the student teachers.

To ensure trustworthiness, the study considered the principles of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The credibility of the study was assisted by the prolonged engagement of 2 years with the student teachers. During this time, I used persistent observation within the lecture room, all data was member checked with participating student teachers, and all student teachers were debriefed about the findings at each cycle. Transferability was ensured using thick description and verbatim evidence from all data sources, and dependability relied on a comprehensive audit of the PAR logistics, process, and aims, which were transparent to all persons participating. Confirmability was ensured by looking for consistency in the findings in more than one form of data. Data collection required corroboration and validation of results during data generation, analysis, and presentation of results (Johnson & Christensen, 2007). In addition, participating student teachers served as co-analysers, monitors, and verifiers of the research process. In the study, triangulation allowed for corroboration using multiple sources of data, multiple methods, and a number of investigators (lecturer-researcher and student teachers) working with the same data.

Examining Students' Words and Actions: A Discussion of the Findings

Race.

Long-term effects of apartheid.

Despite more than 20 years of democracy, South Africa's racialised apartheid past has engendered a society that needs to be understood with reference to this history (Vally, 2002). South Africa's racial history enabled the student teachers in this study to categorise themselves racially with little or no difficulty. At no time during the study did we conceptualise race and all student teachers in the lecture room engaged with the concept without needing to define it. The novel, The Madonna of Excelsior, studied in Cycle 1, proved to be an effective catalyst for them to engage with apartheid South Africa's race laws and attitudes regarding race. Initially, many of them were not keen to do "another apartheid story" because they wanted to "leave the past behind." It is possible that they were weary of an overemphasis of apartheid history that characterised their schooling. Because most of them were born just prior to South Africa's democracy, they did not fully understand how the apartheid laws had been implemented, or the consequences of breaking such laws. Thus, they needed to research laws such as the Immorality Amendment Act (1950), which prohibited sexual relations between white people and people of other races (African, Indian, coloured), the Group Areas Act (1950), which designated racial groups to specific residential and business areas, and the Pass Laws Act (1952), which made it mandatory for African people to carry identification books outside of their designated areas. The Immorality Amendment Act, specifically, featured prominently in the novel, and needed research and explanation.

Yet, despite not having a lived experience of racial laws, the student teachers framed their experiences in racial terms during the class discussion in Cycle 1 dealing with The Madonna of Excelsior with, "white people treat black people that way" as an example. They could recognise being belittled because of their race, with two student teachers noting, "In multiracial schools, they still make you feel inferior. And the teachers say, 'those girls.' I mean, why are we 'those girls?'" and "When lecturers ask you something in a lecture and some of them put on this stupid accent, trying to imitate a black accent. Then, people laugh. I just see it as racist and stupid." The comments exposed a raw emotion of anger that emanated from being demeaned and regarded as the other by persons in authority. The comments also revealed their understanding of how relationships are controlled by power and advantage (Habermas, 1972).

Importance of knowing your past.

The student teachers could recognise why knowing about South Africa's racial past was important. In a written task in Cycle 1, a student teacher noted, "It is only through knowing about the past that one can understand why racism and race are still such sensitive issues in this country." Another student teacher, in a Cycle 1 class discussion, used her knowledge of her racial past to make sense of her life. She reflected, on a very personal level, how the past affected her life. She stated:

My mother, to this day, resents the Boer [Afrikaner] because of how she had to live her life. Her father was white, her mother was black, and she never got to meet her father because of the Immorality Act. If you didn't know the laws of the past, then you wouldn't understand where her hatred stems from.

The examples cited indicated that the student teachers acknowledged that the social, historical, and political context of South Africa, including its racist laws, determined and moulded their private lives. Giroux (2009) noted that students' social, economic, and political backgrounds shape who they are and the values they enact. Similarly, Jansen (2009) reminded us of the importance of unpacking how knowledge, values, and educational contexts are embedded in the social, historical, and political lives of communities.

Incongruences.

The observations in the lectures and tutorials indicated that the student teachers chose to sit in racial groups. When the lecturer-researcher revealed her observation, a student teacher disclosed during reflections on Cycle 1, "I don't like working with some students. They act like we're not there." When asked whom we referred to, no one in the class responded. What was clear was that the student teacher was articulating a feeling of being disrespected and ignored. Of greater concern was that the class collectively would not react to the comment, nor did anyone dispute it or express surprise at hearing it. The reactions indicated an overwhelming feeling of not wanting to engage with perceived racial tensions. The failure to engage in dialogue about racist behaviour is often a "reflection of how deeply entrenched is the fear of putting racial issues on the table" (Lipman 1998, p. 286). It was clear that while the student teachers could not relate to the struggles under apartheid, they were, nevertheless, victims of the long-term impacts of apartheid and carried "the marks of their history" (Soudien 2006, p. 10).

Sensing their resistance to confronting racial and other forms of oppression, I as the lecturer-researcher alerted them, during a class discussion, to the irony of dealing with issues of race in literary texts but being unable and unwilling to confront their own practices and behaviours. After discussions and group reflections on the issue, they acknowledged the need to unlearn behaviours and reflect on the choices they make. It became evident that unless forms of oppression are confronted and discrepancies are disrupted, they can be perpetuated.

Interviews with two student teachers, conducted after Cycle 3, which used the play Sophiatown as its catalyst, provided a different dimension to exploring the student teachers' engagement with the issue of race. The first student teacher revealed that she was the child of a black mother and white father. While she spoke both English and Zulu at home, and both parents could speak both languages, she did not read Zulu books, exclaiming, "Oh no, I can't! That's not literature." Yet she would not look the researcher in the eyes when talking, explaining, "It's a sign of respect in Zulu culture. My mother is very strict about respecting elders." She also revealed that she went to a multiracial high school where most of her peers and all of her teachers were white and "we studied only the classics in English, except one text in Grade 12." When asked if her teachers thought it odd that she failed to look at them when she spoke to them, she answered, "It never came up. Nobody noticed me, I think."

She understood that her language and culture should not be dignified and she constructed her identity by the practices and relations dominating the school. While it is possible that the school knew and accepted Zulu traditions, the student teacher seemed not to be given space for her voice and experiences. In many ways, the school and teachers were using a process of hegemony to support what Giroux (2009) considered to be shared common suppositions of truth. As McLaren (2009) noted, hegemony enables the dominant culture of the school to dominate all groups using consensual social practices. The student teacher indicated the need to value diversity and said, more than once, that she was committed to making a difference to her students. However, three years after leaving school, she still maintained the values and dominant culture of her teachers. As Bourdieu and Passeron (1977) noted, students are rewarded if they support the values espoused by their teachers, and consensual social practices, forms, and structures are internalised by students through the discourses and messages found in everyday, often insignificant, practices, even if they contradict the student's interests.

Another student teacher, a white male, reflected a different view. He insisted that he "did not see race or colour" but said that he could not understand why we had to do a text about "this apartheid thing." He asked, "Why do you people have to go on about the past? So, my ancestors messed up big time. Do I have to take the flak?" On being asked who he was referring to as "you people," he answered, "Everyone . . . lecturers" and repeated that he had a right to his beliefs. He revealed anger when discussing apartheid and, while perceiving his race as being held responsible for South Africa's past, he felt he was being personally attacked because of his whiteness. It was possibly another example of a student teacher tired of, and possibly angry at, hearing "another apartheid story." However, like the white students in Dolby's (2001) study, he appeared to recognise his whiteness within a space of powerlessness and anger, and it became important to engage with his views.

As the cycles progressed, together with the critical reflections and open dialogue, most of the student teachers in the study began recognising the perceived incongruence between espoused and enacted values. When studying The God of Small Things in Cycle 4, the student teachers could identify the struggles surrounding race experienced by the characters in the novel. They could detect the characters in the novel who were in awe of white characters and copied white cultural values and norms, while declaring their opposition to British colonial rule. However, a student teacher noted, in a class discussion, that she knew people, "even in this class, who act white. And then they say we fought for freedom." It became clear that, as time went on, the engagement with issues of race in the literary texts created awareness in the student teachers and they became more astute in recognising tensions between espoused and enacted values related to race. Equally important, like Ladson-Billings' (1999) study found, they could recognise and confront racist practices that they encountered.

Class.

The role of class.

While race is an overt construct that has shaped South Africa's history, the country is also characterised by a class structure, with evidence of unequal economic, social, and political hierarchies (Jansen, 2011). It was thus important for student teachers to interrogate issues of class in literary texts. Most of the participating student teachers recognised the role of class, found in many of their texts, and how it played out in their lives. Class discussions surrounding incidents and characters in Sophiatown, studied in Cycle 3, elicited comments such as, "People react when it's a race thing. But you must see how rich people treat poor people" and "It's a fact, money talks." Another student teacher explained it further, "It's a class thing. Watch how people treat their workers, like they're invisible" and the student teachers appeared to agree with the sentiments. The comments revealed not just an insight into the oppression of one class by another, but also revulsion for such behaviour.

Student teachers also related incidents in the texts to personal events in their lives. In her interview, a student teacher noted:

My mother was pregnant very young and didn't complete her schooling. She suffered for that and she brought us up in a starving home. So, I didn't want to do what my mother did. When I heard the true story of why I was poor, I decided to avoid my mother's actions at all costs.

The student teacher made the link between how poverty shaped her life and how she planned to avoid it.

At the end of the final interview after Cycle 6, a student teacher revealed that she was not going to teach after graduating but planned to begin a Bachelor of Commerce degree, with the aim of becoming a chartered accountant. She explained: "I'm doing it for my child. You say make life better. I have to do it for her. I grew up with nothing. I can make a big difference to my child's life." The student teacher's comments indicated that she was able to recognise her potential to make a difference to the lives immediately around her and was prepared to act on this potential. She felt strongly that she could make a big difference to her child's life by possibly earning more as a chartered accountant than as a teacher, pointing to her perception that greater material wealth equated to greater happiness. Her perception was understandable when considering that she grew up lacking material wealth and believed that she was going to make life materially stronger for her family. Her choices revealed that she wanted to move out of her position of economic vulnerability and believed that her choices would change her position in society (Darder et al., 2009).

Teaching class.

The student teachers were also asked in a class discussion, how they would engage learners in a classroom around issues of class. Using the film version of Much Ado about Nothing as a catalyst in Cycle 5, they indicated that learners needed to recognise a "structured society" where "people were treated differently because of their class." Others noted, in a focus group interview, that they would point out the "relationships between servants and those in power," the fact that servants have "very few words to say and use inferior language," and that "the film implies that servants are expected to behave in a savage way." When studying The Tempest in Cycle 6, the student teachers detected that "power is not restricted to one race or gender" and understood that "power and power structures pervade everything." These comments, and those from interviewed student teachers, indicated that many of the student teachers understood the importance of confronting class differences and class discrimination in South African classrooms and beyond. Similarly, hooks (2009, p. 141) affirmed that class issues in the classroom need to be confronted so that the "democratic ideal of education for everyone can be realised."

Incongruences.

Yet, some female student teachers in the lecture room mentioned, maybe in jest, that they would only marry rich men and one student teacher revealed, "I only take lifts from young good-looking guys with good cars, Mercs, BMs. No skoroskoros [broken down cars] for me." It became clear, and was acknowledged by the student teachers, that an element of double standards prevailed in what they judged to be their espoused values as opposed to the way they conducted their lives.

Gender.

Judging the actions of men and women differently.

Issues of power and vulnerability come to the fore when discussing gender, which was understood by the student teachers to refer to the socially constructed characteristics of women and men, and the implications on norms, roles, and relationships, among others. It was clear that the predominantly female class could identify male behaviour that they found offensive. In Cycle 1, using The Madonna of Excelsior as a catalyst, student teachers' comments included, "Men are so animal-like. They look at you and say things. I want to say, 'Do you talk like that to your mother or sister?"' However, when evaluating the character of Niki, a main character in The Madonna of Excelsior, many female students, during the class discussion, judged her very harshly as a "whore" and "a common prostitute," and written responses to a question seemed to confirm their beliefs. This was despite the fact that there were extenuating circumstances to Niki's behaviour such as her abusive husband and her need for revenge against the "madam's" humiliating actions, as pointed out by two males in the class. Despite having very rigid judgments against the character initially, by the end of the class discussions, many of the women in the class acknowledged the possibility that they were stereotyping women and the roles they ought to play. They were learning how to examine and confront their own prejudices (Lane et al., 2003).

During their engagement with Much Ado about Nothing in Cycle 5, the student teachers could discuss issues of gender roles, gender inequalities, gender stereotypes, and sexism. The focus group revealed that they recognised the characteristics of a patriarchal society, male domination, society's different demands on women and men, and the internalisation of domination. A student teacher noted that Shakespeare represented women as "valueless objects" and another reflected, "Women who are confident, forthright, and able to defend themselves are seen as odd or different."

Thus, the student teachers' comments indicated that they could recognise unequal gender representations and the extent of patriarchal oppression. The findings revealed that the student teachers accepted that gender identities do not exist in isolation but are shaped by society, policies, and other influences of social identity (Darder et al., 2009). They understood the importance of confronting gender norms and practices and acknowledged the need to address issues of stereotypes and biases in classrooms (Zeichner, 1993).

However, when studying The Colour of Paradise in Cycle 2, the class discussions revealed varying responses to the character, Hashem, the father of the protagonist. Of concern were the many responses that seemed to indicate that Hashem's behaviour was acceptable because "men behave that way." Thus, while student teachers did not always agree with Hashem's actions, they accepted and understood them because he was a man. The comments during the class discussions and focus group revealed that members of the predominantly female class accepted, and were themselves perpetuating, patriarchy. This finding reinforced Chege's (2005) findings that patriarchy is accepted in societies where rigid gender stratifications are made to appear normal.

Thus, an unpacking of their responses was necessary, and the student teachers interrogated, in small incremental steps through the different PAR cycles, the discrepancies in their espoused and enacted values. Knowing the "right" espoused answer in relation to a literary text needed to be placed alongside their enacted answers and self-evaluated. Only then was an awareness of the discrepancy created, from which could emerge possible change.

Conclusion

We assumed at the beginning of the study, that the findings from student teachers' engagement with issues of race, class, and gender in literary texts would be a reflection of their engagement with those issues in their daily lives. This was not the case, a finding reflected in the study by Jerolmack and Khan (2014a) who found that what people say is often a poor predictor of what they do. Because the study aimed to have an emancipatory, empowering agenda, it had to endeavour to emancipate and empower all the student teachers by drawing their attention to their own behaviour and how their behaviour may potentially be defying their own words. The study revealed that many of the participating student teachers' espoused values and enacted values and behaviours lacked integrity, and many examples emerged of contradictions in how they judged characters and events in literary texts and how they lived their lives.

However, through the six cycles of the study, the student teachers acknowledged that their behaviour could be reproduced in their own classrooms and thus they could be perpetuating discrimination and prejudice-behaviour that this study aimed to highlight and change. It soon became clear that unless forms of oppression are confronted and discrepancies are disrupted, they could be perpetuated. As the cycles progressed and discrepancies were disrupted, the student teachers became increasingly able to confront their own and their peers' lack of behavioural integrity, as discussed in the findings. For me as the lecturer-researcher, this was one of the successes of this participatory action research study.

The participating student teachers established that teachers of literature, or any other subject, in a postapartheid, postconflict South Africa, need to critically reflect on their practices, confront their prejudices, and recognise that student teachers "carry the marks of their history" (Soudien, 2006, p. 10). In addition, they need to support their teaching practices by well thought-out philosophical and ideological underpinnings (Ladson-Billings, 2009) that will shape their identities as teachers. A failure to do so could result in a perpetuation of oppressive practices in their classrooms and a possible negation of the spirit of both the CAPS (DBE, 2011a, 2011b) and the South African Constitution (1996).

While the student teachers in the study appeared to demonstrate incongruence between their espoused and enacted values as they related to race, class, and gender, the various reflections and discussions made them think, reconsider, and open up the possibility for change. It is possible that the participating student teachers' awareness of the contradictions in their espoused and enacted values will enable their continued critical reflection on their journeys as teachers. As they use their skills to interrogate literary texts, it is possible that their experience of critical reflection will engender ongoing interrogations of themselves, both personally and professionally.

References

Ajzen, I., Brown, T. C., & Carvajal, F. (2004). Explaining the discrepancy between intentions and actions: The case of hypothetical bias in contingent valuation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(9), 1108-1121. [ Links ]

Biesta, G. J. J., & Tedder, M. (2006). How is agency possible? Towards an ecological understanding of agency as achievement. Working Paper 5. Exeter, UK: The Learning Lives Project. [ Links ]

Boog, B. W. M. (2003). The emancipatory character of action research, its history and the present state of the art. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 13(6), 426-438. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. (1977). Reproduction in education, society and culture. London, UK: SAGE. [ Links ]

Branagh, K., Evans, S, & Parfitt, D. (Producers), & Branagh, K. (Director). (1993). Much ado about nothing [Motion Picture]. United Kingdom & United States of America: Renaissance Films, American Playhouse Theatrical Films & BBC Films.

Brewer, R. M. (1999). Theorising race, class and gender: The new scholarship of black feminist intellectuals and black women's labour. Race, gender and class, 6(2), 29-47. [ Links ]

Carroll, D., Featherstone, H., Featherstone, J., Feiman-Nemser, S., & Roosevelt, D. (2007). Transforming teacher education. Cambridge, USA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Chege, J. (2005). Interventions linking gender relations and violence with reproductive health and HIV: Rationale, effectiveness and gaps. Agenda, Special Focus, Gender Culture and Rights, 114-123.

Cochran-Smith, M. (1991). Learning to teach against the grain. Harvard Educational Review, 51(3), 279-310. [ Links ]

Comber, B. (2001). Classroom explorations in critical literacy. In H. Fehring & P. Green (Eds.), Critical literacy: A collection of articles from the Australian literacy educators (pp. 90-111). Newark, USA: International Reading Association. [ Links ]

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act No. 32 of 1961.

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act No. 110 of 1983.

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act No. 108 of 1996.

Crenshaw, K. W. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of colour. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299. [ Links ]

Darder, A., Baltodano, M. P., & Torres, R. D. (Eds.). (2009). The critical pedagogy reader. New York, USA: Routledge. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education. (2011a). Curriculum and assessment policy statement (CAPS): First additional language. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education. (2011b). Curriculum and assessment policy statement (CAPS): Home language. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Dolby, N. (2001). White fright: The politics of white youth identity in South Africa. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 22(1), 5-17. [ Links ]

Francis, D., & le Roux, A. (2011). Teaching for social justice education: The intersection between identity, critical agency, and social justice education. South African Journal of Education, 31(3), 299-311. [ Links ]

Ghaemnaghami, A., Karimi, M., Mahabidi, M., & Sarab, M. (Producers), & Majidi, M. (Director). (1999). The colour of paradise [Motion Picture]. Iran: Varahonar.

Giroux, H. (2009). Teacher education and democratic schooling. In A. Darder, M. P. Baltodano, & R. D. Torres (Eds.), The critical pedagogy reader (pp. 438-459). New York, USA: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gopinathan, S., Tan, S., & Chao, E. (2008). Transforming teacher education. Singapore: International Alliance of Leading Education Institutes. Retrieved from https://www.nnstoy.org/download/preparation/Transforming%20Teacher%20Education%20Report.pdf [ Links ]

Group Areas Act No. 41 of 1950.

Habermas, J. (1972). Knowledge and human interests. London, UK: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Hemson, C. (2006). Teacher education and the challenge of diversity in South Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Henning, S. D. (1993). The integration of language, literature, and culture: Goals and curriculum design. ADFL Bulletin, 24(2), 51-55. [ Links ]

hooks, b. (2009). Confronting class in the classroom. In A. Darder, M. P. Baltodano, & R. D. Torres (Eds.), The critical pedagogy reader (pp. 142-150). New York, USA: Routledge. [ Links ]

Immorality Amendment Act No. 21 of 1950.

Jansen, J. D. (2009). Knowledge in the blood: Confronting race and the apartheid past. Stanford, USA: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Jansen, J. (2011). Fixing a class-based calamity. In M. Mbeki (Ed.), Advocates for change: How to overcome Africa's challenges). Johannesburg, South Africa: Picador Africa. [ Links ]

Jerolmack, C., & Khan, S. (2014a). Toward an understanding of the relationship between accounts and action. Sociological Methods and Research, 43(2), 236-247. [ Links ]

Jerolmack, C., & Khan, S. (2014b). Talk is cheap: Ethnography and the attitudinal fallacy. Sociological Methods and Research, 43(2), 178-209. [ Links ]

Johnson, B., & Christensen, L. (2007). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. Los Angeles, USA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Ken, I. (2010). Digesting race, class, and gender: Sugar as a metaphor. New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Krog, A. (2012, August). The place of literature in South African politics. Paper presented at Edinburgh World Writers' Conference, Cape Town, South Africa.

Kuo, J. (2005). Teaching ESL/EFL students to recognise gender bias in children's literature. TESL Journal, 11(11), 2-8. [ Links ]

Ladson-Billings, G. (1999). Preparing teachers for diverse student populations: A critical race theory perspective. In A. Iran-Nejad & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Review of research in education (pp. 211-247). Washington, USA: American Educational Research Association. [ Links ]

Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). Fighting for our lives: Preparing teachers to teach African American students. In A. Darder, M. P. Baltodano, & R. D. Torres (Eds.), The critical pedagogy reader (pp. 460-468). New York, USA: Routledge. [ Links ]

Lane, S., Lacefield-Parachini, N., & Isken, J. (2003). Developing novice teachers as change agents: Student teacher placements "against the grain." Teacher Education Quarterly, 30(2), 55-68. [ Links ]

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, USA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Lipman, P. (1998). Race, class and power in school restructuring. Albany, USA: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

McLaren, P. (2009). Critical pedagogy: A look at the major concepts. In A. Darder, M. P. Baltodano, & R. D. Torres (Eds.), The critical pedagogy reader (pp. 61-83). New York, USA: Routledge. [ Links ]

McLaren, P., & Baltodano, M. P. (2000). The future of teacher education and the politics of resistance. Teaching Education, 11(1), 47-60. [ Links ]

Mda, Z. (2002). The madonna of Excelsior. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Miller, S., Williamson, P., & Bolf-Beliveau, L. (2011). Applying the CEE position statement Beliefs about Social Justice in English Education to classroom praxis. English Education, 44(1), 63-82.Native Resettlement Act No. 19 of 1954. [ Links ]

Pass Laws Act, 1952.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, USA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2006). Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. Thousand Oaks, USA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Robinson, M., & Zinn, D. (2007). Teacher preparation for diversity at three South African universities. Journal of Education, 42, 61-81. [ Links ]

Ross, L., & Nisbett, R. E. (1991). The person and the situation: Perspectives of social psychology. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Roy, A. (1997). The god of small things. London, UK: Flamingo. [ Links ]

Rusch, E. A. (2004). Gender and race in leadership preparation: A constrained discourse. Educational Administration Quarterly, 40(1), 14-46. [ Links ]

Savvidou, C. (2004). An integrated approach to teaching literature in the EFL classroom. The Internet TESL Journal, 10(12). Retrieved from http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Savvidou-Literature.html [ Links ]

Sayed, Y., Badroodien, A., Salmon, T., & McDonald, Z. (2016). Social cohesion and initial teacher education in South Africa. Educational Research for Social Change, 5(1), 54-69. [ Links ]

Schachter, E. P., & Galili-Schachter, I. (2012). Identity literacy: Reading and teaching texts as resources for identity formation. Teachers College Record, 114(5), 1-37. [ Links ]

Shakespeare, W. S. (1623). Much ado about nothing. Retrieved from https://www.opensourceshakespeare.org/views/plays/playmenu.php?WorkID=muchado

Shakespeare, W. S. (1913). The tempest. Cape Town, South Africa: Juta & Co. (Original work published 1623). [ Links ]

Soudien, C. (2006). Disaffected or displaced? A brief analysis of the reasons for academic failure amongst young South Africans. The international journal on school disaffection, 4(1), 6-13. [ Links ]

Sumara, D. J. (1998). Fictionalising acts: Reading and the making of identity. Theory into Practice, 37(3), 203-210. [ Links ]

The Junction Avenue Theatre Company. (1988). Sophiatown. Cape Town, South Africa: David Philip. [ Links ]

Vally, S. (2002). Violence in South African schools. Current issues in comparative education, 2(1), 80-90. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K. (1993). Connecting genuine teacher development to the struggle for social justice. Journal of Education for Teaching, 19(1), 5-20. [ Links ]