Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Educational Research for Social Change

On-line version ISSN 2221-4070

Educ. res. soc. change vol.6 n.2 Port Elizabeth Sep. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2017/v6i2a2

ARTICLES

Teachers as curriculum leaders: towards promoting gender equity as a democratic ideal

Shan Simmonds

Research Unit for Education and Human Rights in diversity, Faculty of Education Sciences, North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa. Shan.Simmonds@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Curriculum is a site of political, racial, gendered, and theological dispute. Teachers who acknowledge this and see the implications for democratic living embrace their teaching practice as curriculum leaders and participate in complicated conversations. With the focus on gender equity as a democratic ideal, this article explores the lived experiences of some South African female teachers. From the findings, it became evident that some teachers still experience their school contexts as pervaded with patriarchy and sexism, and often fear confronting these traditional discourses. Engaging with subject matter that is likely to cause conflict or confrontation is avoided by some teachers because they do not feel comfortable in such contexts. However, some teachers do emerge as activists for gender justice and create awareness of injustice. These teachers are curriculum leaders who advocate for social change. This article concludes by putting forward some suggestions for how teachers can promote social change through their teaching practices.

Introduction

A school culture that prizes inclusive learning and so promotes diversity and social justice is the cornerstone of democratic societies. However, social justice-orientated understandings still continue to give inadequate attention to curriculum theory, curriculum theorists, and cultural politics (Ylimaki, 2012). Pinar (2012, p. 198) cautioned that teachers need to be in control of their curricula because "until what they teach permits ongoing curricula experimentation according to student concerns and faculty interest and expertise, school 'conversation' will be scripted, disconnected from students' lived experience and from the intellectual lives of the faculty." In the postmodern era, teachers need to take full account of the sociocultural and political factors that determine what is taught, to whom, and by whom (Slattery, 2013). As they do so, teachers can begin to embody curriculum leadership.

Teachers as curriculum leaders see curriculum as a complicated conversation (Pinar, 2012). Unlike teachers who implement curriculum to attain course objectives, they are aware that ideologies (e.g. neoconservative, neoliberal, and neonationalist) permeate education systems and that curriculum decisions are political acts (Ylimaki, 2012, p. 305). As a complicated conversation, curriculum involves finding the interrelationship of academic knowledge, subjectivity, and society in considering the past, the present, and the future (Pinar, 2012, p. 47). These complicated conversations are underpinned by an understanding of the intellectual labour of curriculum through "disciplinarity" (Pinar, 2007, p. xii). Teachers as curriculum leaders engage with curriculum as a site of political, racial, gendered, and theological dispute (Henderson & Kesson, 1999; Pinar, 2007). Comprehension, critique, and reconceptualisation of the intellectual history of the discipline (verticality) are intertwined with an analysis of its present circumstances-horizontality-(Pinar, 2007, pp. xiii-xv). This inevitably political activity takes account of the moral dimensions of a curriculum. As McCutcheon (1999) pointed out, curriculum can never be objective or value free. Accordingly, ethical curriculum leadership has to be collaborative and democratic.

For Henderson (2010), curriculum leadership is the antithesis of curriculum management and instructional leadership. The chief concern of curriculum management is business efficiency and it uses positional authority rather than collaborative engagements with various stakeholders to inform curriculum decisions (Henderson, 2010, p. 221). Instructional leadership focuses on the advancement of innovative teaching practices and policies rather than the epistemological and ontological dimensions of curriculum as a complex interplay with academic knowledge, society, and the self (Pinar, 2012; Ylimaki, 2012). In contrast, teachers as curriculum leaders demonstrate a "disciplined theoretical position on innovative curriculum work" (Henderson, 2010, p. 221). This is done in a way that integrates a deep understanding of their subject matter as embedded in the democratic self and social understanding: their curriculum goal-setting, decision-making, and reflective activities facilitate subject matter meaning making, interactions with and conceptions of society, and the processes of self-formation in a context of active and collaborative democratic learning (Henderson & Gornik, 2007, pp. 11-13).

McCutcheon's (1999) conception of curriculum leadership as deliberation is valuable in the context of gender equity as a democratic ideal. Her theory strives for a "good" democratic society that is informed by collaborative decision making in an ethical context and underpinned by the feminist ideal of consciousness raising (McCutcheon, 1999, p. 40). Against the backdrop of these perspectives, this article engages with gender discourses (parity, equality, and equity) from feminist perspectives of sameness and difference. Thereafter, particular South African female teachers' experiences of gender parity, equality, and equity and their implications for teachers as curriculum leaders are explored. Finally, possible ways in which teachers as curriculum leaders can foster gender equity as a democratic ideal are suggested.

Gender Parity, Equality, and Equity: Feminist Perspectives of Sameness and Difference

Sameness and difference discourses come into play in engagements with the constituents of gender and its various interpretations. A gender sameness perspective strives "to extend to women the same rights and privileges that men have through identifying areas of unequal treatment and eliminating them via legal reforms" (Pilcher & Whelehan, 2004, p. 38). Emphasis is placed on sameness in terms of social status and legal and political rights commonly associated with gender equality (Lorber, 2012, p. 329). Feminist theory has offered two main criticisms of gender equality. In the 1960s and 1970s, gender equality was regarded as "uncritical equality" because of the uncritical way in which women were positioned in a masculine pattern of life (Hughes, 2002, p. 34). The assumption was that equality could be achieved through gender neutrality or androgyny. The other main criticism of gender equality relates to its "uncritical reversal" of gender roles that gives higher value to females than males (Hughes, 2002, p. 34). In effect, it is so fixated on hierarchy reversal that gender equality amounts to the "measurement" of access and power (Hughes, 2002, p. 36). Pilcher and Whelehan (2004, p. 39) cautioned that the resultant gender equality is "achieved through the assimilation of subordinated groups (women, gay men) into the values, institutions and lifestyles of the dominant groups (men, heterosexuals)." A form of gender equality that works in terms of only dominant groups can be a form of gender inequality for minority groups.

Equal rights feminism or formal equality uses elements of the sameness discourse as it strives to "achieve equality through legislative means in order to secure the rights of the individual" (Hughes, 2002, pp. 41-42). Ashiagbor (1999, p. 150) listed four types of equality informing legal definitions and processes of law: fundamental equality of individuals (all human beings are universal and therefore equal), equality of opportunity (meritocratic access to opportunities such as employment), equality of condition (attempts to make conditions of life equal), and equality of outcome or results (requires some form of legislative or other intervention to compensate for inequality).

This perception of gender equality began the challenge of breaking down traditional gendered binaries through legal reforms. These gave women access to male-dominated spheres of society and demonstrated that "women are more than capable of performing tasks usually allotted to men" (Pilcher & Whelehan, 2004, p. 27). One avenue that has granted women access is affirmative action, a legal reform "bringing women to occupations and professions dominated by men and promoting them to positions of authority" (Lorber, 2012, p. 331). However, these rights-based movements have been criticised for their "propensity to maintain the hierarchical, competitive and individualizing organization of society" (Hughes, 2002, p. 55). In addition, there is no "recognition of and valuing of the ways in which women are different from men" (Pilcher & Whelehan, 2004, p. 39), only how they are the same.

According to Evans's (1995) theory of difference, there are three schools of difference. These are: (i) valuing that women are different to men, (ii) acknowledging that there are differences between groups of women and men, and (iii) recognising differences within groups of women and men. These schools engage with different shades of difference. In one sense, liberal feminism and equality feminism cannot be said to be the point of departure in that difference is not acknowledged per se, but only in the shadow of sameness. Perspectives such as multicultural feminism and critiques of white, bourgeois women's movements advocate that "sameness equality [be] replaced by an understanding of identity divisions and disadvantages based on issues of gender, race, class, sexuality and disability" (Hughes, 2002, p. 63). The concept of identity politics, which highlights Young's (1990) notion of politics of difference, is directly related to this discourse.

For Young (1990), being attentive to the potential of a difference discourse to cause dividedness is pivotal. She contended that differences are not neutralised or transcended and that "different groups are always similar in some respects and always potentially share some attributes, experiences and goals" (1990, p. 171). In this respect, equality exists among and within different groups so that difference creates a safe space for respect and affirmation of each other in all our differences: "Difference now comes to mean not otherness, exclusive opposition but specificity, variation and heterogeneity" (Young, 1990, p. 171). Difference as exclusion and segregation is rejected in favour of a "relational understanding of difference" that takes into consideration both "similarity and difference" (Young, 2000, p. 90).

This difference discourse opens up the possibility of juxtaposing difference and sameness. Hughes (2002) argued that two stances can emerge as a result. One is an equal but different stance, in which women and men are granted the same rights and freedoms, but a woman is different in this setting because she is "naturally the homemaker and carer of children" (Hughes, 2002, p. 46). The ways in which social roles are gendered is thus not challenged because the point of departure is the "natural calling" of the woman-maternal or motherhood (Hughes, 2002, p. 47). The other is the equal and different stance that was adopted during the interwar years when women became part of paid labour. In many instances, women have had to choose between foregoing their "maternal duties" and engaging in "equal competition with men in the workplace" or accepting their "traditional roles within the home" (Hughes, 2002, p. 47). Choosing both initiates an employment and maternal paradox. A lack of support and recognition emanates from a failure to take account of women's ways of knowing and reasoning (Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, & Tarule, 1986; Gilligan, 1982).

From a poststructuralist stance, these sameness and difference stances are not ultimately fruitful or even desirable. On one hand, sameness "fails to recognize the socially constructed and patriarchal nature of the criterion of evaluation deemed pertinent to social inclusion" (Plicher & Whelehan, 2004, p. 39). On the other hand, difference "fails to theorize the extent to which 'maleness' and 'femaleness' are themselves socially constructed and also underplays the significance and plurality of other forms of difference" (Plicher & Whelehan, 2004, p. 39). What is required is a perspective that interrogates and goes beyond the binary opposition of difference and sameness, and minimises an attempt to "homogenize experience to fit a predetermined model" (Pilcher & Whelehan, 2004, p. 29). Ghorashi and Sabelis (2012, p. 81) argued that these essentialist constructions risk "fixing people's (identity) position."

Redefining difference from a diversity perspective recognises the plurality of many differences that enable us to "discover new ways of understanding ourselves and each other" so that "our differences are less likely to be used against us" (Sawicki, 1991, p. 45). Pilcher and Whelehan (2004, p. 40) elaborated further by advocating that a diversity perspective deconstructs the dichotomy of either sameness or difference and argues for a combination of both. I view the sameness and difference discourse proposed here as difference within sameness, and sameness within difference. One could ask: "The same as what or whom, and different from what or whom?" There are no simple answers to these questions because power and privilege are always context bound. For example, while it is possible for a woman to have power and privilege in the workplace, she may not have it in the home for religious and cultural reasons. Haraway's (1991) conception of situated knowledge is illuminating in this regard:

Gender is a field of structured and structuring difference, where the tones of extreme localization, of the intimately personal and individualized body, vibrate in the same field with global high tension emissions. Feminist embodiment, then, is not about fixed location in a reified body, female or otherwise, but about nodes in fields, inflections in orientations, and responsibility for difference in material-semiotic fields of meaning. Embodiment is a significant prosthesis; objectivity cannot be about fixed vision when what counts as an object is precisely what world history turns out to be about. (p. 195)

In addition, sameness and difference discourses present binaries within binaries. The tendency to regard gender as men or women, positions all women into one category and all men into another. One could read this discourse as sameness in gender (both homosexual), but difference in sex (one male and one female). hooks (2000) has shown that one needs to take into account other aspects such as class, race, and ethnicity. The term contiguity, coined by Oseen (1997), is therefore more useful. It allows one to view sameness and difference side by side and, thus, nonhierarchally and without sameness as the norm or the anchor by which difference is constituted. She proposed conscious inclusion of others into nonhierarchical and nonessentialising relationships through relational power forms that make explicit taken-for-granted power relations (Oseen, 1997).

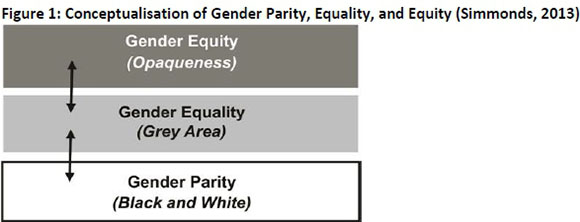

Sameness and difference discourses also influence how gender parity, equality, and equity are conceptualised. For Aikman and Unterhalter (2005), gender parity, equality, and equity are not in binary opposition but are intertwined and interdependent. Gender parity measures gender access, change, and opportunities quantitatively (Aikman & Unterhalter, 2005, p. 3). In this sense, genders are treated equally, and they participate as equals through legislative forms. If access is provided for all people, then gender parity is achieved. In this sense, gender parity is mainly value free and holds a gender-free or gender-neutral stance (Simmonds, 2013). In Figure 1, this dimension is presented in black-and-white because of its narrow aspiration and one-dimensional representation of gender (Simmonds, 2013).

In contrast, gender equality can be described as "respect for human rights and a set of ethical demands for securing the conditions for all people, men and women, to live a full life" (Aikman & Unterhalter, 2005, p. 3). It requires "the removal of deeply embedded obstacles and structures of power and exclusion, such as discriminatory laws, customs, practices and institutional processes, all of which undermine opportunities and outcomes" (Aikman & Unterhalter, 2005, p. 3). The strength of this view of gender equality is that it does not reduce gender equality to legal reforms driven by gender neutrality (Lorber, 2012, p. 331). It also views gender equality as a grey area because gender is not completely value free and transparent (see Figure 1).

For Aikman and Unterhalter (2005, p. 3), gender equity becomes the interrelatedness of gender parity and gender equality as it seeks to "characterize institutional and social processes that work" towards parity and equality. This entails "putting in place the social and institutional arrangements that would secure these freedoms" (Aikman & Unterhalter, 2005, p. 3). As such, gender equity becomes a necessary condition for social justice (Guerrina, 2000, p. 441). At the same time, gender equity can be depicted as gender opaqueness because of its elusiveness and sometimes impenetrable nature (Simmonds, 2013). Although gender equity resides in matters of gender parity and gender equality, it is often subtly disguised and multilayered. As such, it is aware of the injustices produced by agency and structure and seeks to challenge and disrupt these.

From a curriculum leadership stance, gender equity has more to offer than gender parity and equality. It promotes being "fair and just" to all genders "to show preference to neither and concern for both" (Klein, Ortman, & Friedman, 2002, p. 4). In giving "attention to ways that women and men, boys and girls are not homogenous groups but crosscut by cultures, religions, racial identities, ethnicities, social classes, sexualities and other major statuses" (Lorber, 2012, p. 331), it recognises the intricate , elusive, and opaqueness of gender. In effect, gender equity emphasises the need to embrace inclusivity and diversity and to acknowledge that gender is a multilayered ethical, moral, and social construct (Simmonds, 2013). This is in keeping with the commitment of curriculum leadership to social transformation through curriculum as a complicated conversation (Henderson, 2010; Pinar, 2007).

Research Methodology

This article focuses on part of a larger project entitled, Curriculum Implications for Gender Equity in Human Rights Education (Simmonds, 2013), which explored how female teachers and learners experience gender equity. Making meaning of the experiences of these participants has proved important for curriculum scholars involved in human rights education curricula. Within a qualitative design, this project engaged with narrative inquiry as "a way of understanding experience . . . over time, in a place or series of places, and in social interaction with milieus" (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000, p. 20). Situated in critical feminist research, this study aimed to depict experiences in what Clandinin and Connelly (2000) and Creswell (2012) termed a three-dimensional space that takes account of the complex interrelatedness of an individual's interaction, continuity, and situation.

Data were collected from six female teacher participants using 60-minute-long, semistructured interviews. These interviews made it possible to explore complex and subtle phenomena rather than straightforward and verifiable facts (Denscombe, 2010, p. 172). Teachers were asked open-ended questions related to their personal and professional experiences of gender equity. These questions included how they engaged with gender equity in the formal curriculum, their experiences of being female teachers in their particular school contexts, and their experiences of their interactions with the learners they teach. What these teachers all had in common was their employment to teach secondary school learners between the ages of 13 and 18 years. These teachers were purposefully selected because they were teaching subjects that deal with gender-related topics. These subjects included life orientation, history, and religion studies. The teachers represented a diverse group in terms of their location, years of teaching experience, home language, and nationality. Three teachers were located in an urban area of South Africa and the other three in an inner-city area. Their teaching experience ranged from two to 30 years. Although both schools teach through the medium of English, the teachers were not all mother-tongue speakers of English. Their nationalities, South African and Zimbabwean, added to their diversity. All the participants confirmed that they were comfortable to be interviewed in English and to be voice recorded so that accurate transcriptions could be made. The use of critical discourse analysis made it possible to give attention to the role of discourse in the production and reproduction of power, abuse, and domination, thus taking seriously the experiences and opinions of individuals and giving voice to their encounters with (in)equity (Fairclough, 2001; van Dijk, 2001).

Ethical requirements were met throughout the research process. Ethical clearance was obtained from my institution, the Department of Basic Education, the principal of each school, and the participating teachers. As part of obtaining informed consent from them, the participants were explicitly informed that the research data generated would be disseminated in the form of publications and be used for a number of educational purposes. The participants were assured that pseudonyms would be used to protect their identities and that they were free to withdraw from the research at any stage in the process for whatever reason, without any consequences.

A possible limitation of this research could be its focus on female teachers. However, the research should be seen as part of the larger project confined to exploring female teachers and learners' experiences of gender equity. Seen in that light, it can be viewed as a significant contribution to a particular area of scholarship. The main findings that emerged from the semistructured interviews are presented next.

Research Findings: Female Teachers' Experiences

From the findings, it is evident that female teachers had experienced varying degrees of gender parity, equality, and equity. These forms include their engagements with the formal curriculum, personal encounters, and their professional roles as teachers. The three main findings are depicted as follows: (i) formal curriculum as conflict and contestation, (ii) personal experiences of patriarchy and sexism, and (iii) female teachers as activists for gender justice and awareness.

Formal curriculum as conflict and contestation.

Thembi was teaching religion studies and Setswana at an urban school. Mbali was teaching life orientation (which focuses on human rights education, careers, physical education, and religion) at an inner-city school. These teachers both experienced the formal curriculum content that they taught as sites of conflict and contestation.

In the extract below, Thembi explains that she prefers to avoid any gender-related topics because in her experience they lead to fights and conflict amongst her learners:

I touch on it here and there, but I don't usually want learners to read too much into it because it causes conflict. .. . So that is why I just want them to understand that we treat each other equally. We just respect that each of us are different and understand that we have to accept it. That's all. . . . Here [at school] we have different groups, different cultures, we have different people, even foreigners. . . . That is why I am saying . . . just keep it there, don't put too much into the learners, don't bring that subject too much into learners because if you do that, they will start comparing and if they start comparing, then that's when the fight will start. So just keep it on the surface.

To avoid the conflict that Thembi refers to above, she says she must just teach her learners the facts "about the religion . . . when did it start . . . do they pray . . . what are the differences between religions." In fact, Thembi mentions "gender equity, all that stuff, no, I don't think it needs to feature" in religion studies. She acknowledges that her learners are more likely to engage with gender-related topics as "something that came from the street, or out when it was a break time" and "when it arises you have to handle it" in the classroom.

Thembi's experiences make it evident that gender-related topics do not feature in her teaching and when they do feature, she adopts a gender-neutral and value-free stance underpinning a gender parity perspective (Aikman & Unterhalter, 2005, p. 3). Her stance reveals a superficial understanding of the interrelatedness of gender equity in religion studies. This might be due to her inexperience, lack of confidence in, or fear of, navigating conflict so that it can be embraced as transformative pedagogy. Mbali's experiences of contestation in her teaching practice of life orientation are somewhat different from Thembi. Mbali does engage with gender-related topics but as tradition or culture in proximity to human rights. Within this dynamic, Mbali has experienced her curriculum as a space of contestation.

You know it's difficult because of the difference with Western culture. For the learners, it's not something that they know about. But they are interested to learn about it. So if we are talking about it in class they will ask questions like, but is it not violating the rights of that person? . . . virginity testing of girls . . . initiation school for boys. For them there is a clash between someone's culture and the constitution. And then I will try to explain that a culture is something that we choose . . . a constitution is something that overrules the country. So that's why I say you have a choice to do it. Whether you are a black girl, you have a choice to say no, I don't want to follow this, I want to do this. The constitution of the country overrules everything. But culture is something that we create as a group and say, this is our culture.

For Mbali it is important to have these types of discussions with her learners so that they can be exposed to the complexity of cultural practices (such as virginity testing and initiation school) in proximity to their human rights. As such, she acknowledges gender equality through "respect for human rights and a set of ethical demands for securing the conditions of all people, men and women, to live a full life" (Aikman & Unterhalter, 2005, p. 3). For Mbali, "with most of the topics they are addressing in class, everyone participates" so as to also encourage inter-dialogue between learners "so that they can learn from each other." As a result, Mbali acknowledges the formal curriculum as a space of contestation and capitalises on this by approaching her curriculum as academic knowledge that cannot be disconnected from the self and society (Pinar, 2012).

Personal experiences of patriarchy and sexism.

Valarie and Jabu refer to the gender discourses they encounter through the content of the subjects that they teach. However, what makes the accounts of these female teachers unique is their experience of patriarchy and sexism in their particular school contexts.

In the interview, Valarie shares her experiences as a history teacher in an inner-city school. She expresses her views of historical events such as the Women's March 1956 in South Africa and the 1798 Women's March to Versailles during the French Revolution to attest to the long struggles that women have endured to gain a better life. She uses these examples to attest to the struggles she still faces as a female teacher who has been teaching for 30 years. Her experience is twofold. On the one hand, she is critical of the requirements to conform, and be acknowledged by her male colleagues. She experiences this as sexism, explaining that the male teachers have their own agendas and do not prioritise the learners. She uses the example of sports events such as athletics, cricket, and rugby, which are supposed to be about the learners but the male teachers use this as chance to "sit back" and "drink." If you "don't drink with the men you are non-existing" and these male teachers "gossip about you . . . be rude to you . . . and tell dirty jokes about you." It makes it difficult to work as a team with her male colleagues and she says her other female colleagues conform because they want to feel accepted even though "they complain but they are always too scared to go and report" their male colleagues. At one stage, the context in which Valarie was working became so hostile for her that she "left teaching for a while" and looked for a teaching position at another school (Valarie). Her leaving teaching could have been due to the isolation and discouragement she experienced.

She also experienced patriarchy and sexism when she wanted to apply for a management position. She explained that she was not even afforded the opportunity to apply: "The principal came to me and he said listen don't even apply because they want a man." What "irritates" her is that she knows that she had the necessary "development skills" but she was told that she "must remember, if a toilet breaks a woman can't fix it." Valarie's response at the time was that she "can always pick up a phone and call a plumber if the toilet breaks." However, she was still not afforded the opportunity to apply for the promotion to a management position and she describes this as "rather despicable." This narrative reveals that education management continues to be male-dominated and, as such, perpetuates a patriarchal system of governance.

Jabu, a teacher in an urban area, regards it as disturbing that her manager perceives male teachers to be better suited to teach certain subjects. She shared the following experience:

I remember the director saying that he's looking for a male teacher to teach science subjects because women cannot teach that. No, no, no, I don't want girls to be hindered from doing science subjects. No, they need to be given the opportunity to prove themselves, to try it and see that it's not that hard. They might even discover they are even better at it than boys.

For Jabu, it is frustrating to work in her patriarchal and sexist school environment. She actively confronts her situation by explicitly including gender-related topics in her teaching and encouraging her learners to share their views. She explains:

I ask the boys, do they think girls should do physics? . . . Can women be pilots or should they stick to nursing and teaching? . . . If they say no, I ask them why. If they say yes, I ask them why.

Jabu's teaching and the agency she has in her classroom becomes the safe haven she needs to boycott the sexism she encounters amongst her male colleagues.

Both Valarie and Jabu's accounts of their experiences depict their school contexts at collegial and management level as sites of patriarchy and sexism. It is evident that these female teachers express their discontent through advocating for gender equality in their positions as professionals as well as through the curriculum context that they teach. This is reflected in their activism for "the removal of deeply embedded obstacles and structures of power and exclusion, such as discriminatory laws, customs, practices and institutional processes, all of which undermine opportunities and outcomes" (Aikman & Unterhalter, 2005, p. 3).

Female teachers as activists for gender justice and awareness.

As life orientation teachers, Methembe (from an urban school) and Sherry (from an inner-city school) portray themselves as activists for gender justice and awareness. For Methembe, this is formalised in the girl network that she initiated at her school, whilst for Sherry it is more informal.

Methembe, a teacher with expertise in counselling, has a vision to "make girls see that they are more than just women, they can do much more." This stems from her knowledge of the global girl-child network initiative, and from her frustrations of her school only "introducing clubs like knitting, sewing, soccer, or netball." The girl network

meet as a group every Wednesday . . . and talk about the issues of a girl-child. It involves things like teenage pregnancy, academic school work, child-headed homes, not coping because of stress back home . . . abuse . . . experimenting with drugs, going clubbing the whole night and being into groupies. . . . The main thing that I have experienced now of late is girls trying to keep appearances. You are aware that you come from a poor background and your friends are having nice hairstyles in school, they are having nice phones and at the end of the day the girls get a sugar daddy who buys them things and they exchange those favours with sex. They end up getting STD's, end up being HIV positive, and end up getting pregnant.

She says that the girl network is a success because there is "that element of confidentiality between me and the girls." The success also lies in her approach to not just "discuss social issues and their opinions" but to all involve learners actively through "researching these topics on the Internet to find out more about them." One of her main aims is to

help learners balance the scale so that they get educated, respect themselves, avoid teenage pregnancy, focus on their careers and work hard towards their goals so that they can be better citizens of tomorrow and strong women. . . . At the end of the day, when you look at these girls they are confident in what they do. When you look at them you see they have changed drastically from the things that they were doing.... They look like they have woken up, they look bright, they look hopeful.

For Sherry, her role as an activist for gender justice and awareness emerges naturally in her teaching and during informal interactions with her learners. Teenage pregnancy, in particular, is common at her school-so much so that "the scariest thing is that everyone is very blasé about it: "Oh well she's going to have a baby," as if "they don't understand how serious it is." She recalls that sometimes even the parents "are really laid back" because they themselves were teenage mothers. As a result of her context, she made teenage pregnancy an explicit part of her curriculum.

There is no use lying about it. I need to be open and honest about sex. Use the correct terminology for genitalia: vagina and penis. . . . Explain what is going to happen if you have sex, every action has a reaction, if you don't use a condom you will fall pregnant.

Besides being transparent about sex and using pedagogical knowledge and practical demonstration (for example, with "bananas and condoms") with learners, she also promotes the values of responsibility and accountability. In her experience, the "boys say the girls are pregnant and that is their problem to deal with" without acknowledging that "both should take responsibility, because it takes two to tango." She explains that it is important for her to engage with the role of boys in teenage pregnancy. She does this by addressing topics on what it will entail if the parents "keep the baby, have an abortion or pursue adoption," so that they have "more knowledge of how to treat the situation instead of thinking that the girl got pregnant and that is her problem." The boys must "realise that the girl is not alone, they have got to fit the bill" and take shared responsibility and accountability. She even goes as far as to "include questions about it in the exam."

Girls confide in Sherry as "somebody to give them concrete advice." Girls feel comfortable to approach Sherry when they need someone to turn to and she welcomes it. She tells the girls, "if something happens, rather come and speak to me" because from her experience girls say, "I can't tell my mom or I am scared of my mom." First she will have a discussion with the girls to determine "how are we going to solve the problem . . . and then involve the parents and involve the doctor and take it from there." Sherry does not want the girls to feel alone and hopeless about their situation so she walks the journey with them and does what she can to "help them to cope."

For Methembe and Sherry, it is part of their professional duty as teachers to be activists for gender justice and create awareness. They achieve this by being support structures to learners as well as equipping learners with the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values needed to improve their situations. They are concerned with the real-life challenges and experiences faced by the girls in their school so as to bring about greater awareness and change. As such, they are less concerned to advocate for parity and equality for girls than to promote gender equity as a necessary condition for social justice (Guerrina, 2000, p. 441).

Discussion: Teachers as Curriculum Leaders Who Promote Gender Equity as a Democratic Ideal

The experiences of the female teachers highlight the implications that their gender discourse stances on parity, equality, and equity have for their teaching practice. When gender-related topics lead to conflict and confrontation, teachers are inclined to avoid them altogether (Thembi) or regard them as a legal construct (Mbali). On a more personal note, teachers' lived experiences of gender injustices such as patriarchy and sexism manifest themselves in their teaching practice as a campaign for women to be treated the same as men (Valarie and Jabu). A more proactive approach is possible when teachers are activists for gender justice and use their teaching practice as a platform to create awareness and change. This could resonate as a formal initiative (Methembe's girl network) or through the formal and hidden curriculum (Sherry). Methembe and Sherry reaffirm that teachers can be curriculum leaders who promote gender equity as a democratic ideal. Their experiences attest to Henderson's (2010, p. 223) conception of curriculum leadership as taking "an ecological approach to educational innovation," guided by the critical analysis of social issues from their historical developments and current contemporary state to "encourage deliberative judgments that advance the enduring values of democratic living." As for Thembi, Mbali, Valarie, and Jabu, their teaching practice could be enriched if they were to "engage in critical reflection of the histories, sociocultural, and political realities that shape [their] leadership narratives, lives and ultimately, the content of education (curriculum)" (Ylimaki, 2012, p. 343).

To be curriculum leaders who promote gender equity as a democratic ideal, teachers "need a broad range of analytical tools and curriculum perspectives to examine underlying assumptions behind policy language and curriculum content decisions at school" (Ylimaki, 2012, p. 344). Such analytical tools might be embedded in the type of questions that teachers ask to inform their teaching practice. Henderson (2010, p. 223) proposed that curriculum leaders ask questions such as:

• Does my teaching encourage and sustain well-informed, moral judgements on social issues that are relevant to my learners?

• Do I challenge myself to deliberate and reflect on real social, political, historical, and economic problems with breadth and depth and transfer this to my learners?

• If so, is my moral orientation consistent with a democratic social contract that encourages deliberative judgements to advance the enduring values of democratic living?

• Do I understand that as a teacher I occupy a vital public intellectual role in society and that my responsibilities extend beyond subject matter instruction?

• Do I base my teaching on a comprehensive, ecological approach to educational innovation as a collaborative process?

One of the curriculum perspectives that teachers could fruitfully entertain is Pinar's (2007) theory of curriculum as a complicated conversation through disciplinarity. This theory

calls for curriculum theorists, practitioners, and students with shared concerns to work with communities and schools, taking to heart the concerns of all involved, to cultivate integrity, beauty, social justice, and an ever-evolving sense of humanity that seeks to protect and renew a biosphere on the brink of peril. (Schubert, 2009, p. 142)

In effect, teachers as curriculum leaders must engender a comfort with the inherent contentions and disputes that they encounter and approach these as necessary conversations for change. This requires disrupting the comfort zones of classrooms and school environments infested with gender injustices. Creating supportive environments for each other, teachers can embrace their struggles and successes as shared visions. Aspiring for transformative pedagogy as a priority, gender equity can become a democratic ideal.

Conclusion

Ylimaki (2012, p. 343) contended that "research is needed to explore curriculum leadership identities and struggles through a range of critical perspectives including feminist and critical race theories." This article has endeavoured to respond to this call by using gender and feminist theory perspectives to unlock the female teachers' experiences and advocate for teachers as curriculum leaders who promote gender equity as a democratic ideal. Teachers need to have the courage, knowledge, and commitment to depart from traditional discourses and expectations and engage in complicated conversations towards social transformation (Henderson & Gornik, 2007; Pinar, 2012; Ylimaki, 2012).

References

Aikman, S., & Unterhalter, E. (2005). Introduction. In S. Aikman & E. Unterhalter (Eds.), Beyond access: Transforming policy and practice for gender equality in education (pp. 1-12). Oxford, UK: Oxfam. [ Links ]

Ashiagbor, D. (1999). The intersection between gender and race in the labour market: Lessons for antidiscrimination law. In A. Morris & T. O'Donnell (Eds.), Feminist perspectives on employment law (pp. 139-160). London, UK: Cavendish. [ Links ]

Belenky, M. F., Clinchy, B. M., Goldberger, N. R., & Tarule, J. M. (1986). Women's ways of knowing: The development of self, voice and mind. New York,USA: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, USA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Boston, USA: Pearson Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Denscombe, M. (2010). The good research guide for small-scale social research projects (4th ed.). Berkshire, UK: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Evans, J. (1995). Feminist theory today: An introduction to second-wave feminism. London, UK: SAGE. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. (2001). Critical discourse analysis as a method in social scientific research. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (pp. 121-138). London, UK: SAGE. [ Links ]

Ghorashni, H., & Sabelis, I. (2012). Juggling difference and sameness: Rethinking strategies for diversity in organizations. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 29(1), 78-86. [ Links ]

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice. Cambridge, USA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Guerrina, R. (2000). Sex equity v. sexual equality. In L. Code (Ed.), Encyclopedia of feminist theories (pp. 440-441). London, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Haraway, D. (1991). Simians, cyborgs and women: The reinvention of nature. London, UK: Free Association Books. [ Links ]

Henderson, J. G. (2010). Curriculum leadership. In C. Kridel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of curriculum studies (Vol. 1, pp. 220-224). London, UK: SAGE. [ Links ]

Henderson, J. G., & Gornik, R. (2007). Transformative curriculum leadership (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, USA: Merrill/Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Henderson, J. G., & Kesson, K. R. (1999). Understanding democratic curriculum leadership. New York, USA: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

hooks, b. (2000). Feminist theory: From margin to center (2nd ed.). Brooklyn, USA: South End Press. [ Links ]

Hughes, C. (2002). Key concepts in feminist theory and research. London, UK: SAGE. [ Links ]

Klein, S., Ortman, P., & Friedman, B. (2002). What is the field of gender equity in education: Questions and answers. In J. Koch & B. Irby (Eds.), Defining & redefining gender equity in education (pp. 3-28). Greenwich, USA: Information Age. [ Links ]

Lorber, J. (2012). Gender inequality: Feminist theories and politics (5th ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

McCutcheon, G. (1999). Deliberation to develop school curricula. In J. G. Henderson & K. R. Kesson (Eds.), Understanding democratic curriculum leadership (pp. 33-46). New York, USA: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Oseen, C. (1997). The sexuality specific subject and the dilemma of difference: Rethinking the different in the construction of the nonhierarchical workplace. In P. Parsad, A. J. Mills, M. Elmes & A. Prasad (Eds.), Managing the organizational melting pot: Dilemmas of workplace diversity (pp. 54-80). Thousand Oaks, USA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Pilcher, J., & Whelehan, I. (2004). 50 key concepts in gender studies. London, UK: SAGE. [ Links ]

Pinar, W. (2007). Intellectual advancement through disciplinarity: Verticality and horizontality in curriculum studies. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense. [ Links ]

Pinar, W. (2012). What is curriculum theory? (2nd ed.). New York, USA: Routledge. [ Links ]

Sawicki, J. (1991). Disciplining Foucault: Feminism, power and the body. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Schubert, W. H. (2009). A response to Curriculum work at the intersection of pragmatic inquiry, deliberation, and fidelity by James G. Henderson and Kathleen R. Kesson. Educational Researcher, 38(2), 142-143. [ Links ]

Simmonds, S. (2013). Curriculum implications for gender equity in human rights education (Doctoral dissertation). North-West University, South Africa. [ Links ]

Slattery, P. (2013). Curriculum development in the postmodern era: Teaching and learning in an age of accountability (3rd ed.). New York, USA: Routledge. [ Links ]

Van Dijk, T. (2001). Multidisciplinary CDA: A plea for diversity. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (pp. 95-120). London, UK: SAGE. [ Links ]

Ylimaki, R. M. (2012). Curriculum leadership in a conservative era. Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(2), 304-346. [ Links ]

Young, I. M. (1990). Justice and the politics of difference. New York, USA: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Young, I. M. (2000). Inclusion and democracy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [ Links ]