Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Educational Research for Social Change

versión On-line ISSN 2221-4070

Educ. res. soc. change vol.5 no.2 Port Elizabeth sep. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2016/v5i2a9

ARTICLES

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2016/v5i2a9

Embedding community-based service learning into psychology degrees at UKZN, South Africa

Jacqui AkhurstI; Vernon SolomonII; Carol MitchellII; Mary van der RietII

IRhodes University, South Africa. J.Akhurst@ru.ac.za

IIUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

ABSTRACT

From 1999 to 2002, the centrally funded Community-Higher Education Service Partnership (CHESP) aimed to drive community engagement in several South African universities. It intended to develop socially accountable models of meaningful student engagement in communities. This led to community-based service learning (CBSL) being embedded into a number of psychology modules for over a decade (progressing from undergraduate to postgraduate levels of study) at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), Pietermaritzburg campus. CBSL resonated with many psychology students' motivations to make contributions to socially disadvantaged groups. Evaluation of such initiatives in the South African context are necessary, to assess their contributions and the challenges posed. Three levels of student experience in CBSL modules were considered, using qualitative methodology in order to understand the value of the modules and to draw lessons for deepening the connection between higher education and its social and community contexts. Data about their experiences were collected from focus groups of UKZN students and an interview with the undergraduate-level tutor. The students reported the value of seeing how psychological theory can be applied, and of the ability to "give something back" to communities. In addition, they learned to work in respectful and participatory ways, enhancing their ability to problem-solve. The findings illustrate progressive shifts in students' understandings of the applications of psychology and its potential role; they also evidence the growth in students' critique and social awareness. Recommendations are made for integrating and enhancing local community engagement, and highlight important considerations when students, community partners, and faculty staff interact in community-based initiatives.

Keywords: Community-based, service learning, curricular integration, community engagement in higher education, reflective learning

Introduction

McGovern and Brewer (2013) referred to "a three-legged stool of faculty activity: teaching, scholarship, and service" (p. 507). As a result of democratisation, South African universities have been tasked with providing "service" through participating in key communities in their environments, providing tuition that facilitates students' community engagement, and fostering the principles of democratic citizenship (Council of Higher Education [CHE], 2006). Community engagement in South African higher education has thus evolved from being one of three elements alongside teaching and research, to being integrated into teaching and research activities (Lazarus, Erasmus, Hendricks, Nduna, & Slamat, 2008). This article aims to contribute to the South African literature in which there is limited evidence of the ways in which the three strands of activity are integrated and operationalised in the teaching of psychology.

The integration of community engagement with teaching and research has been challenging in the South African context. Proponents of integration argue that this engagement should be a scholarly activity, that is, the scholarship of engagement (Boyer, 1990); others (for example, Butin, 2007) argue that the integration of community engagement activities into mainstream higher education practices serves to dilute the disruption these activities may bring to standard university business. Community engagement activities may disrupt the knowledges promoted in universities by drawing on local knowledge, cultural understandings, and practices, which may conflict with the (mostly) Western models students are taught. Community engagement has resource implications for higher education institutions, especially when a separate office is created with staffing and resource costs. Thus, when activities are integrated into curricula, there are reduced needs for separate funding and additional support because many of these are absorbed into existing teaching-related structures, and students may also help with picking up some of the associated costs such as travel.

Many students are motivated to study psychology because they would like to help others (Bromnick & Horowitz, 2013; Goedeke & Gibson, 2011). This is evidenced by the substantial numbers who do voluntary community-based work, prompted by their sensitivity to issues of social justice. This potentially links with preparation for employment because the "third sector" (e.g., non-profit-making organisations, charities, and social enterprises) provides a potential career destination for graduates of psychology. In most undergraduate and honours-level psychology curricula, however, there are limited opportunities for students to experience "psychology in action"-and in the current context of resounding calls to decolonise the curriculum (Mbembe, 2015), the challenge for psychology is to move from predominantly Westernised approaches to more transformational knowledge creation and engagement. In addition, given calls for universities to promote social responsibility, psychology students need to understand the relevance of their studies to societal and global issues (Trapp & Akhurst, 2011). For these intersecting reasons, it is important to consider integrating community-based service learning (CBSL, more commonly termed service learning in the USA) into the curriculum to meet these needs and better prepare students for their roles as citizens.

Drawing on constructivist approaches to understanding the links between thought and language (Deeley, 2015), service learning has its theoretical origins in Dewey's philosophy of education for democracy (as cited in Hatcher, 1997) and Boyer's (1990) scholarship of engagement. Service learning has become popular because it is a pedagogy that engages both students and faculty in their communities in ways that are intended to be educationally meaningful to all those involved (Bringle & Duffy, 1998). There are various different forms of service learning globally, and in many settings it has been "re-territorialised" (Le Grange, 2007) to ensure a better fit with the context.

Service learning, on the whole, aims to promote the transformation of student perspectives and practices (Felten & Clayton, 2011). This transformation is thought to take place as the real-world experiences challenge students' preconceptions, and reflection activities assist them to develop new understandings. A critical service learning approach requires students to move beyond reflection to take action by exposing power imbalances and social inequities (Rhoads, 1997); it also requires students to use academic inputs and apply these to their service in a larger context-in order to consider the structural causes that compel their service (Mitchell, 2008).

The important features of CBSL are, therefore, experiential education in a community setting where students actively reflect on their community-based experiences in the light of their course content, making links between their work and course material to societal needs, thus enhancing their civic responsibilities (Hatcher & Bringle, 1997). The CBSL term is used in the context of this article because it foregrounds the community-based partnerships that are essential to this work.

The positive impact of such experiences on students' learning are reported across academic, civic, personal, social, ethical, and occupational domains (Tharp, 2012). Perry and Katula (2001) noted that community-based experiential learning may play a powerful role in developing students' awareness of their civic responsibilities, highlighting contextual issues (social, political, economic, and historical) that impact on people's well-being. In addition, through relationship building, students engage in the realities of community members' daily lives-encouraging them to consider more deeply the impact of environmental conditions and the "impress of power" (Smail, 2008).

Drawing on work in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, Mitchell and Humphries (2007) provided evidence of the ways that CBSL challenges students' ideas, creating a sense of disequilibrium that can motivate them to search for explanations. Much of the US-based literature thus emphasises the importance of accompanying CBSL with structured opportunities to reflect systematically, drawing on the concepts, theories, and models learned in psychology. This reflecting process is based on experiences, makes links to theory, and in this discursive interaction, tests the relevance of theory in real-world contexts. Reflection is therefore emphasised as an important aspect of course delivery (Eyler, Giles, & Schmiede, 1996) that needs to be well integrated in order to provide opportunities for the sort of transformational learning described by Mezirow (2003).

The work to be reported in this article evolved from some of the authors' earlier involvement (19992002) in a South African programme to promote higher education institutions' community engagement. The Community-Higher Education Service Partnership (CHESP) was a 3-way partnership (Mouton & Wildschut, 2005) developed to promote the reconstruction of South African civil society through "the development of socially accountable models for higher education, research, community service and development" (Lazarus, 1999, p. 2). Through CHESP, universities were encouraged to design activities and projects to enable students to work with community partners in order to generate new ideas and research evidence, to engage in knowledge exchange, and to influence policy and practice relevant to societal issues.

In the psychology department at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) Pietermaritzburg (PMB) campus, the original project partnered academics with a peri-urban school and the local circuit of the provincial education department to provide assistance to educators providing lifeskills lessons, and opportunities for learners to be listened to when encountering personal difficulties. CBSL was subsequently expanded and integrated into the psychology curriculum to work in a number of schools linked to an educators' cooperative that aimed to provide psychological assistance, and resulted in the associated CBSL being embedded into some psychology modules.

This article focuses on the ways in which the students experienced the embedded nature of CBSL, and their progressive learnings at different levels of study. It aims to draw from the students' rich accounts to make recommendations on ways that such activities might contribute to the advancement of community-engaged psychology teaching in South Africa. For an additional perspective, the authors also investigated the experiences of the tutor who facilitated critical reflection sessions with the undergraduate students. The research question that we endeavoured to answer (from the students' perspectives at various levels, and that of the undergraduate tutor) was: "How was CBSL experienced and how did it impact on students' learning, their understandings of psychology, and the promotion of social change?"

Design of the UKZN community-based work placement

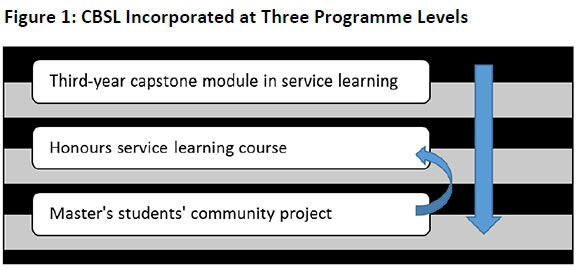

At UKZN (PMB) up until 2014, psychology students were afforded the opportunity to participate in service learning at various points in their programmes. The three levels at which CBSL was incorporated are shown in the figure below.

In the final undergraduate year, students were able to elect to participate in a third-year capstone CBSL module that aimed to synthesise meaningfully various aspects of their learning over the course of their psychology degree. In this course, students provided lifeskills lessons at local schools (hosted by a community partnership with the educators' cooperative, Sizabantwana [Helping children], Mitchell & Jonker, 2013). The students reflected on their experiences from the perspective of psychological theory, and critiqued theory in the light of their experiences. Students worked in pairs with a mentor contact in the school, visiting their placement every week over a 10-week period, and were encouraged to see their roles as development practitioners within a community of practice that evolved with their peers in the module.

Students who proceeded to an honours degree could then elect to do a further CBSL module requiring students to conduct psycho-educational workshops at various sites in the city. This module was facilitated by master's students at a more advanced level. The honours students' learning could be further complemented by other modules, for example, social or community psychology. The master's students were in their first year training as applied psychologists and, within their coursework element, they were involved in CBSL by working with both the community of honours students and by negotiating with community-based partners about the work of the honours students. The master's students also facilitated the honours students' reflection on their experiences in small groups, then in turn, they reflected on their own engagement and learning, in seminars and in their final reports.

To complete their module requirements, students reported these experiences in a variety of ways. All levels of students participated in group activities with their peers in a course-related setting. In addition, the third-year and honours students were required to keep and submit learning journals as formative tools to help them track their learning through the course over time. These were used to promote the development of critical thinking and reflection skills, facilitated through submissions to the tutors or master's students (in the case of the honours students) for feedback. This learning journal became a conversation between the student and the facilitator. This encouraged them to consider their skill development and increased understanding of the theories they had covered and seen come to life or challenged in their placement (e.g., they could choose theories related to motivation, social learning, social psychology, or developmental practice).

All levels of students were required to write a reflective report, as an examination equivalent, providing a summative opportunity for students to formally reflect on their learning. In addition, at the third-year level, students were required to do a presentation about their experiences, with the community partners being invited to attend and give their own feedback about what it was like to host the students.

Methodology

Research design

A qualitative, interpretive approach was chosen for this study because the experiences of the students and the tutor were paramount (Terre Blanche, Kelly, & Durrheim, 2006). This approach allowed a rich understanding of the students' experiences, and thick descriptions were sought to answer the research questions. Data were collected from two focus group interviews with students: one with master's students (n = 6) and the other with honours students who had completed the third-year module the previous semester (n = 12). Students were recruited by requesting volunteers during their honours and master's lectures. In addition, an individual interview was conducted with a tutor from the previous year's third-year module.

The students were allocated pseudonyms so that confidentiality was ensured. There was no direct benefit to the students through their participation and there was no risk of them suffering negative consequences as a result of the research, because the interviews were conducted by one of the researchers who is external to the university. The other authors do not know who volunteered to participate. The research received ethical approval from the Humanities and Social Science Research Ethics Committee in May 2012 (UKZN: HSS/0235/012). The study protocol ensured all requirements for informed consent for participation, for audio recording of participation, anonymity, and confidentiality were met. In addition, the right to withdraw without consequence was met and participation was voluntary without the use of incentives.

After negotiation with students for their permission to use these data, the interviews focused on questions related to students' motivations for choosing the modules and their experiences of CBSL. Thematic analysis and constant comparative methods were used to analyse these data (Braun & Clarke, 2006); this involved coding the transcribed data into themes, with members of the research team separately extracting key findings. These were then cross-checked and synthesised in order to develop findings about the benefits and challenges for students and the nature of their learning. Dependability and confirmability were ensured by keeping a detailed record of the data collection methods and analysis. The trustworthiness of the study (Babbie & Mouton, 2005) was enhanced by the researchers comparing and discussing the themes, as noted above.

Findings

Experience of undergraduate community-based service learning module: Students

The first part of the findings is selected from the data collected from the honours students' retrospective accounts of their learning in the undergraduate course. Students' verbatim words are quoted with the relevant focus group transcription line in brackets as (FG x).

Giving back In psychology

Students described their experiences as being helpful both to themselves and others, stating that "the whole point of psychology" is to promote "better mental health of the public" (FG 15 & 16) and emphasising, "you're not being a psychologist for yourself" (FG 17). They valued the opportunity to give "some of the things they're not getting from their teachers" (FG 24). Thus, giving at the same time as providing some form of service enabled students to share their knowledge and provide something from their "advantageous positions as university students" (FG 17).

Reasons for choosing the module

A number of subthemes emerged from the data, including "an opportunity for doing something different" (FG 30), to apply their knowledge in a community setting, but also as a "break from" (FG 31) the predominance of theoretical courses in their programme because the module was seen as more practical. Some self-interest was evident in choosing the module because it had no examination attached, but students acknowledged the value of the alternative assessments, including the learning they gained from doing presentations. They recognised the importance of the experiences for enhancing their CVs, because they perceived this as being an advantage to those wanting to be selected into postgraduate study programmes. Students also spoke of it potentially enhancing their career prospects, for example, helping them to choose teaching (or not), to gain some exposure to counselling, and to develop their creativity and spontaneity along with enhancing their patience and self-confidence.

Contributions in the schools

An element that was emphasised by a number of students was their concern for the "kids" with whom they had interacted. They recognised that school learners were often reluctant to talk to their educators for various reasons, but that they seemed more willing to talk to the students. The students saw their closeness to the learners' age group as being helpful, because "we've all faced similar things" (FG 97), and that they were able to provide "things they're not getting from their teachers" (FG 24). Students thus recognised that they provided a complementary contribution to the educators' input.

Facing realities

The students, however, emphasised the challenges of the reality of the work. They saw it as "more than" presenting a lesson but being "a support network . . . kids trusted us" (FG 163), and that they needed to help the children to get along. Some found it "rewarding" (FG 189) but found that some of the topics that they needed to deal with were difficult, for example, those related to alcohol and drugs; sexuality, rape, and abuse; violence, including corporal punishment; and intercultural relations, racism, bullying, and teasing.

The value of learning to apply psychological theory in real life

The student focus groups concurred that their experiences had enhanced deeper insights into the applications of psychological theory. They noted a sense of the impact of being able to give something back to communities. In addition, they reported learning to work in a respectful and participatory way, and that this had improved their abilities to problem-solve when confronted with difficult issues in the community settings.

Experience of undergraduate community-based service learning module: Tutor

In the second part of these findings, the above students' accounts are juxtaposed against those of their tutor, who had taken on the role as a replacement lecturer for the third author at the time of the students' experiences as reported.

Purpose of the service learning

The tutor reported that he perceived the purpose of the module as "a real-world opportunity for students to connect theory with practice whilst giving back something to the community . . . and in turn then benefiting from having this kind of practical experience." He noted that the ideal was to go into the community "to forge a new community of practice and hopefully that these new practices will emerge or unfold through this equal collaboration." This highlights the extension of community of practice ideas beyond the class group. He then noted problems of potentially imposing theory, rather than it emerging organically from the field. Furthermore, in the reflection sessions, students needed to outline the theory "that they think might be useful to explain something but then, finding it quite difficult to grapple with the so-what? and now-what? questions" that required them to consider the implications of the theories discussed.

The tutor commented on the importance of CBSL for the students to be giving back to communities in contrast to extractive research approaches, and that the undergraduate students taking on a development practitioner role was an appropriate way to enable this. He had seen that the students felt some nervousness and anxiety going into the schools, but were also "eager to get out there and teach these lessons."

Difficulties in the partnership relationship

A limitation of the approach was that in the partnerships with schools, the students had taken on roles more akin to teacher assistants, leading to "the sense from a lot of them that they felt like they weren't really making a difference in the community because they could not actually establish a community of practice" with the learners in such "a short space of time." He felt that a teacher role led to a continued power asymmetry, rather than promoting collaborative work with the learners.

Some of the students experienced having their agency constrained by what the educators required of them; in some schools, learner discipline was difficult for the students, demotivating some of them.

This highlighted the tensions involved in negotiating the students' role. In some settings, the educators (those who were not the nominated school mentors that had negotiated with the tutor) had not understood the purpose of the students' engagement, thus undermined them by reportedly saying, "they're just student teachers they don't really know what they're talking about so don't worry about them." These difficulties do not emerge to the same extent from the students' focus group text, perhaps emphasising the tutor's role to troubleshoot in instances where such disjunctures between students' and educators' perceptions occurred.

Facing realities

The tutor expanded further on the students' comments about the challenges posed by psychosocial problems that they encountered and the difficult topics that students were expected to cover in some lessons. The reflective meetings each week, and possibilities of consultations with the tutor were thus important provisions for students needing to deal with "all kinds of concerning things that were put in question boxes like reports of abuse or suicidal ideation." For some educators, the students' willingness to assist was helpful:

in terms of the educators not having to negotiate those things in class but maybe having younger or authentic voices coming into the classroom to talk about drugs or alcohol, abuse or sex or whatever it might be . . . that would have more meaningful impact.

A number of educators reported in their evaluation reports and at the end of course poster symposia, that they saw the students' presence as a benefit to them and to the learners.

Perceived benefits for the students

The tutor emphasised three aspects: (i) the value of having done structured community service, enhancing the possibility of selection into postgraduate studies; (ii) that the course promoted a greater interest "in critical social theory and social change in development issues and in practice," and that he could see the carry forward of this in their honours studies when "the same sort of ideas that were starting to mature then have now come into a fruition and they refer back to the course frequently"; and (iii) that it clearly promoted the students' critical thinking, because they are encouraged to question far more than in other courses.

Broadening and sustaining the experience

Finally, the tutor raised the question of expanding the sites of undergraduate students' experience beyond the schools' partnership. Whilst he acknowledged that this might pose additional logistical difficulties, he thought that if:

there was some way they could get involved at like, a community centre, where there are already structures in place to deal with psychosocial issues and there might be a counsellor on site or experienced people at hand, that this might lead to a better community-based experience.

He also noted the challenge of sustainability of projects when students are only involved for a semester, stating that it is "impossible to establish a community of practice . . . in such a short space of time, so . . . realistically, it is a sort of service to the school and then a service back to the university." Thus, these students' experiences were perhaps more in the realm of service learning than the more complex, community-based learning.

Experience of postgraduate community-based service learning module

The final part of these findings incorporates elements of the learning experiences as described by the focus group of masters' students, with participants identified as (P x), where students were in the final stage of the process as envisaged in Figure 1. All had experienced previous CBSL in their undergraduate or honours years (and half of the group had gone through the whole process from undergraduate through honours to master's activities, facilitating the honours students' engagement); in addition, two thirds of this group had also had prior volunteering experiences. In their accounts of the different elements of CBSL, the development of their skills is evident-from working on the life orientation lessons in their first more structured undergraduate exposure, through more open-ended mentoring with some developing their own rights-based programmes for delivery during their honours course, to their more facilitative and partnership building roles and networking activities at master's level. It was clear from their accounts that the building of one set of activities on another in subsequent years of study provided for growth in their skills and for taking on greater levels of responsibility as they progressed.

Challenges to theory

In their facilitation of less experienced students' learning, they noted that

theory doesn't always apply and It doesn't always work . . . you can go and apply theory and realise that the world Isn't, It Isn't based on theory . . . people are social creatures . .. so seeing the real aspect of psychology rather than the stuff that we are being taught to know how to know people and to know how to change people and make them better. (P 5)

The students emphasised the way that CBSL played a role in Africanising their curriculum: "So when you want to be a psychologist in South Africa . . . you need to know what is actually practically happening . . . then you realise that the theoretical and the practical sometimes clash" (P1). For example, one reflected that in the honours year, "we need to understand that people often behave in collective ways, they don't always behave in individual ways, so in our African culture, that is a large part of how people often make their decisions" (P 2).

They spoke of briefing their assigned groups of students to challenge notions, emphasising the need for being flexible and adaptive in response to contextual demands: "A lot of people leave their undergrad degrees, especially, thinking that they can go out there and change the world and they are just going apply these things that they have learnt and it's going to work perfectly" (P2). They drew from their own insights, for example,

I mean before that [honours course] I had nothing, I just thought that I wanted to help people and if you want to help people, you've just got to be Oprah instead. But I want to do more than help people . . . I want to make impact. (P 6)

The importance of collaborative relationships

Their insights enabled them to learn how to form relationships, to feel deeper levels of respect and to work more collaboratively in problem solving, gaining awareness of their "own shortcomings" (P 4). For example, the experience

changed me as well. . . just because we are psychologists, we kind of have this idea that, we are "superior" and the service learning I have done have kind of cut me off at the knees, and made me realise that I am not better than anyone else. (P 5)

The students thus learned to be more open-ended in negotiations of activities, relinquishing their control as they related to the perspectives of community members:

This has taught me that you can't function In Isolation and we have had to go with what they want, even if we think we know better because that is what the community needs or feels they need or want. So you've got to be able to change and deal with people in a calm way. (P 3)

Problematising community and privilege

The master's students provided more nuanced discussions of the notions of community, for example, confronting honours students' ideas that "community is owned, it is impoverished, people don't have money there" (P 6). They also noted the challenges of building more authentic and collaborative partnerships with community groups: "There was this expectation that because we come from the university, so there's that whole . . . we have this power thing. Things that they need, there's more of 'just give us what you can give us and we will take it'" (P 3). Their accounts illustrated the way in which they had confronted their notions of privilege and learned to build more authentic relationships with diverse people. Two examples are: "You don't know what it is like for other people. . . . But when you get in there . . . you just form relationships with them and you start breaking down these boundaries" (P 5), and "From all my service learning modules I have learned something about myself, and about other people and the world. I didn't just go in there and 'save the poor children'" (P 2).

Ideas about charity are thus challenged and the master's students changed their views of community needs, recognising the reciprocity of changes in themselves and the people with whom they interacted. One noted:

You start learning different things, you start seeing things in a different way. . . . But you actually go into a small community . . . and you learn, and they learn and you have a big impact on them, on the individuals, just by being there sometimes. (P 1)

They thus noted that being there could send a message of solidarity while they also gave a number of examples where their work had led to changed circumstances for others.

The value of a systemic, sustainable perspective

In addition, such experiences enabled much deeper understandings of the systems at work and the complex dynamics related to resources and the complexities of political influence, as in "I knew that politics affects everything, but not to such an extent as I realised" (P 3). The students valued a more systemic view, "which works from the intrapersonal, interpersonal, organisational, community and policy. . . . And that often an impact in one of these categories . . . leads to flow downwards or upwards" (P 6). Thus, the interconnectedness of different influences on contexts and ways to work towards greater social cohesion were noted as important considerations. They also described the challenges of finding ways to enable the continuation of their work and promoting sustainability of programmes in contexts of limited resources.

Combined reflexive practice

Finally, the master's students noted the important role played by the reflexive activities and the impact of group discussions on deepening their learning. Some examples are:

You end up thinking about things differently. (P 5)

You draw on other people's ideas and opinions, like you would in a community . . . it's a collaborative effort. (P 2)

You work in a group: these are my weaknesses, these are strengths, how can we help each other? And complement each other?. . . You're more effective like in a group." (P 6)

It's group work, because that's how it actually is in the real world, when you're in an NGO or whatever . . . (P 2)

Thus, the exposure to different people's realities and in-depth discussions about positioning, along with a growing awareness of the ethics of building authentic partnerships with enhanced awareness characterise the students' accounts. This form of learning was thus contrasted with traditional learning of individual-based psychology, and was reported to be more meaningful and better suited to the context in which the students will seek to work.

Discussion and conclusion

The findings demonstrate that CBSL enhances the quality of learning both within and beyond the related psychology modules. CBSL supports students' desires to become involved in community-based applications of their discipline, and their aspirations to make some sort of difference through their engagement. Mitchell and Humphries (2007) noted the potential of such engagement for developing participatory research in and with communities, enabling both students and community members to benefit in many ways from such experiences. With regard to the students' experiences, however, the potential emotional impact of this process must be noted in their references to the difficult topics that learners wanted them to address. This underlines the importance of having various support structures in place, ranging from group and tutorial reflective discussions to opportunities for individualised assistance. It is likely though, that the nature of the support needed will have resource implications in an integrated model to be discussed further below.

CBSL provides rich ways of enabling students to see the relevance of the skills gained through study and the theoretical applications of psychology in everyday contexts. Students develop a greater awareness of the potential role of psychology in addressing contextual and contemporary issues, thereby potentially contributing to their "psychological literacy" (Trapp & Akhurst, 2011). It would appear that extending the evidence base and understanding of the impact of these activities through longer-term studies in South Africa is now required in order to gain a richer sense of the effects on students' career planning, career-related thinking, and employability.

This study provided the opportunity to explore a layered approach to CBSL, where the experiences of students across their undergraduate and postgraduate CBSL courses, and one staff member, could be described. The findings appear to indicate a hierarchical progression of the kinds of learning and transformation that takes place as the students continue with their studies.

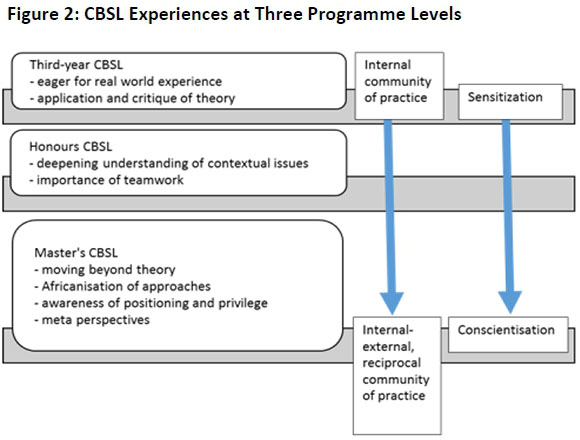

Figure 2 provides a summary of the trends in the students' experiences and transformation. At the undergraduate level, the students are eager for real-world experiences and the opportunity to serve (give back) in communities. Their experiences relate to the challenges of this and their difficulties with the application and critique of psychological theory. At the honours level, the students appear to have a deeper understanding of the contextual issues that relate to their community experience, and start to value the importance of teamwork in dealing with reality. By the master's level, students display a much more nuanced understanding of community-based learning. They appear to use meta-perspectives to reflect on their own privilege and positioning in the work. They question the relevance of theory and speak of the need to Africanise the curriculum.

This layered approach also serves to demonstrate students' different understandings of community and communities of practice over time, where they seem to move from a focus on an internal community of practice (within the class) to one that is more inclusive-drawing on reciprocal relationships with communities. Thus students seem to move from a position of being sensitised by their undergraduate experiences, to being conscientised by their master's year of study. Individual students may achieve this level of awareness at different stages, and some may not have benefitted at all (and thus may not have volunteered for the focus groups). In addition, as students progress through their studies, they are exposed to a variety of courses that may add to their conscientisation. It therefore cannot be claimed that this is solely due to the CBSL experience. However, the CBSL experience seems to be the place where this new awareness is put into practice.

Given the usefulness of these kinds of programmes, there are important considerations related to institutional commitment to this type of learning. As noted earlier, the integration of community engagement activities into "business as usual" may serve to lessen their value in disrupting hegemonic practices in the university. Gelmon, Sherman, Gaudet, Mitchell, and Trotter (2004) highlighted the importance of institutional support for such initiatives, rather than merely the lip service of official statements. In the students' accounts above, the impact of such transformative learning experiences is evidenced. It is clear that such initiatives have the potential to go some way to challenging the colonial forms of disciplinary knowledge that have dominated thus far, and CBSL may play an important role in the calls to Africanise the psychology curriculum. The challenge will be for university systems themselves to be transformed (in particular, the forms of reward and divisions of labour) to become more open to authentic partnership building through each step of collaborating on such programmes, and for resources to be directed more actively to support these more resource-intensive modes of learning and working.

Mitchell and Rautenbach (2005) cautioned against programmes that benefit mainly university students, and where the community partners are not accorded the same power as university staff. A notable limitation of this research, to this point, is that it has taken the perspective of students and staff members without also adequately including the voices of the community partners. Designing and implementing CBSL programmes requires great sensitivity to, and respect for, the work of partners to guard against cultural voyeurism (Dürr & Jaffe, 2012) and the exploitation of the goodwill and hospitality of people. Future research on community partners' perspectives on the usefulness of students' engagements is therefore vital.

To conclude, CBSL presents as a potentially transformative strategy to more deeply connect training in psychology with its social and community context. Structural integration within the tertiary institution, political and resource commitment from within, and a programmed progression of CBSL through undergraduate to postgraduate levels are needed to ensure its value as a contributor to students' development. The voices of community partners need to be heard in order to reciprocally inform CBSL initiatives and curricula-to shift CBSL from community-located and hosted to become genuine partnerships. Such partnerships then have greater potential to connect with the ideals of social justice rather than meeting more minimalist goals of simply enriching individual students' tertiary learning experience.

References

Babbie, E. & Mouton, J. (2005). The practice of social research. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. San Francisco, USA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. [ Links ]

Bringle, R. G., & Duffy, D. K. (1998). With service in mind: Concepts and models for service-learning in psychology. Washington, USA: American Association for Higher Education. [ Links ]

Bromnick, R., & Horowitz, A. (2013, April). Reframing employability: Exploring career-related values in psychology undergraduates. Paper presented at HEA STEM Annual Learning and Teaching Conference, Birmingham, UK. Retrieved from https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/resources/reframingemployability exploring career-relatedvalues in psychologyundergraduates.pdf

Butin, D. (2007). Justice-learning: Service-learning as justice-oriented education. Equity and Excellence in Education, 40(2), 1-7. [ Links ]

Council on Higher Education (CHE). (2006). Service-learning in the curriculum: A resource for higher education institutions. Pretoria, South Africa: CHE. [ Links ]

Deeley, S. (2015). Critical perspectives on service learning in higher education. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Dürr, E., & Jaffe, R. (2012). Theorizing slum tourism: Performing, negotiating and transforming inequality. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 93, 113-123. [ Links ]

Eyler, J., Giles, D. E., Jr., & Schmiede, A. (1996). A practitioner's guide to reflection In service-learning. Nashville, USA: Vanderbilt University. [ Links ]

Felten, P., & Clayton, P. H. (2011). Service-learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 128, 75-84. [ Links ]

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the Oppressed (M.B. Ramos,Trans.). Harmondsworth, Middlesex, UK: Penguin Education. [ Links ]

Gelmon, S., Sherman, A., Gaudet, M., Mitchell, C., & Trotter, K. (2004). Institutionalising service-learning across the university. In M. Welch & S. Billig (Eds.), New perspectives in service-learning: Research to advance the field (pp. 195-217). Greenwich, USA: Information Age. [ Links ]

Goedeke, S., & Gibson, K. (2011). What do new psychology students know about psychology? Australian Psychologist 46(2), 133-139. [ Links ]

Hatcher, J. A. (1997). The moral dimensions of John Dewey's philosophy: Implications for undergraduate education. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 4, 22-29. [ Links ]

Hatcher, J. A., & Bringle, R. G. (1997). Reflection: Bridging the gap between service and learning, College Teaching, 45(4), 153-158. [ Links ]

Lazarus, J. (1999). Towards a model for the reconstruction and development of civil society and the transformation of higher education in relation to community needs. Joint Education Trust Bulletin10, 1-2. Retrieved from http://www.jet.org.za/publications/bulletins/Bulletin10.pdf [ Links ]

Lazarus, J., Erasmus, M., Hendricks, D., Nduna, J., & Slamat, J. (2008). Embedding community engagement in South African higher education. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 3(1), 5985. [ Links ]

Le Grange, L. (2007). The 'theoretical foundations' of community service-learning: From taproots to rhizomes. Education as Change, 11(3), 3-13. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. (2015). Decolonizing knowledge and the question of the archive. Public lecture at Wits Institute for Public and Economic Research, South Africa. Retrieved from http://wiser.wits.ac.za/system/files/Achille%20Mbembe%20-%20Decolonizing%20Knowledge%20and%20the%20Question%20of%20the%20Archive.pdf

McGovern, T. V., & Brewer, C. L. (2013). Undergraduate education in psychology. In D. K. Freedheim & I. B. Weiner (Eds.), Handbook of psychology, Volume 1: History of psychology (2nd ed.), pp. 507529). New York, USA: Wiley. [ Links ]

Mezirow, J. (2003). Transformative learning as discourse. Journal of Transformative Education, 1, 5863. [ Links ]

Mitchell, T. D. (2008). Traditional vs. critical service-learning: Engaging the literature to differentiate two models. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 14(2), 50-65. [ Links ]

Mitchell, C., & Humphries, H. (2007). From notions of charity to social justice in service-learning: The complex experience of communities. Education as Change, 11(3), 47-58. [ Links ]

Mitchell, C., & Jonker, D. (2013). Benefits and challenges of a teacher cluster in South Africa: The case of Sizabantwana. Perspectives in Education, 31(4), 100-113. [ Links ]

Mitchell, C., & Rautenbach, S. (2005). Questioning service learning in South Africa: Problematising partnerships in the South African context. A case study from the University of KwaZulu-Natal. South African Journal of Higher Education, 19(1), 101-112. [ Links ]

Mouton, J., & Wildschut, L. (2005). Service-learning in South Africa: Lessons learnt through systematic evaluation. Acta Academica Supplement, 3, 116-150. [ Links ]

Perry, J. L., & Katula, M. C. (2001). Does service learning affect citizenship? Administration & Society, 33, 330-365. [ Links ]

Rhoads, R. A. (1997). Community service and higher learning: Explorations of the caring self. Albany, USA: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Smail, D. (2008). Psychology and power: Understanding human action. Journal of Critical Psychology, Counselling and Psychotherapy, 8(3), 130-139. [ Links ]

Terre Blanche, M., Kelly, K. & Durrheim, K. (2006). Why qualitative research? In M. Terre Blanche, K. Durrheim, & D. Painter (Eds.), Research in practice: Applied methods for the social sciences (271284). Cape Town, South Africa: University of Cape Town Press. [ Links ]

Tharp, D. S. (2012). A proposed workshop curriculum for students to responsibly engage cultural conflict in community-based service learning. Journal of Transformative Education, 10(3), 177-194. [ Links ]

Trapp, A., & Akhurst, J. (2011). A UK perspective on psychological literacy and citizenship. In J. Cranney & D. Dunn, (Eds.), Psychological literacy and citizenship (pp. 191-205). New York, USA: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]