Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Educational Research for Social Change

On-line version ISSN 2221-4070

Educ. res. soc. change vol.5 n.2 Port Elizabeth Sep. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2016/v5i2a7

ARTICLES

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2016/v5i2a7

Examining aspects of self in the creative design process: towards pedagogic implications

Chris de Beer

Durban University of Technology, South Africa. chrisdb@dut.ac.za

ABSTRACT

I am a practising jewellery designer and artist who lectures at a university of technology in South Africa. The aim of this study was to deepen my understanding of my own creative design process so that I can better facilitate my students' creative development. I used the little-c (everyday creativity) definition of creativity as a framework for analysing work that I exhibited in a self-study research exhibition. By analysing the space in which I worked and the objects I produced, I looked to see how aspects of self manifested within the process of producing creative artefacts. This was a qualitative study in a transformative paradigm, using autoethnography as methodology. The analysis was done by conducting an autoethnographic interview with myself, and then analysing the responses. To ensure trustworthiness, I show several images of my creative work in situ. I also use a convention of nested text boxes to show the relationship between my reflections and meta-reflections. The study produced several key realisations that could leverage pedagogical implications: the creative process is not linear, serendipity can be harnessed, play should be encouraged, and personal experience can be incorporated in the creative design process. Autoethnographic research into my own creative design process made visible the richness of personal histories and local contexts as resources for learning and teaching about creativity and, more broadly, as resources for social change.

Keywords: Self-study, creative design process, autoethnography, exhibition, self-interview

Background

I am a practising jewellery designer and artist who lectures at a university of technology in Durban, South Africa. One of my lecturing duties is to teach my students how to design and manufacture jewellery-not only conventional jewellery that can be sold in commercial jewellery shops, but contemporary jewellery that engages with a "diverse range of contemporary social, environmental, technical or artistic trends" (Quickenden, 2000, p. 1). Developing unique contemporary South African jewellery could play a part in the long-term growth of the jewellery industry and contribute to social change by creating an awareness of, and cultivating an appreciation of, local and indigenous resources. I feel that this can be achieved if we, as designers, were to draw on our personal and private lives and then incorporate these influences in our creative design process. I want to encourage this personalised approach to the creative process by formulating briefs that include a private or personal aspect with my students in the jewellery design studio.

The objective of my research, therefore, is to gain an understanding of my own creative design process in relation to the development of contemporary South African jewellery, and to explore the pedagogical implications inherent in this understanding. I use autoethnography to examine my creative process because it affords me the use of "personal experience to examine and/or critique cultural experience" (Holman Jones, Adams, & Ellis, 2013, p. 7), particularly as designing jewellery necessitates an awareness of the various roles that it can play within one's culture: those of portable wealth, indicator of status, and spiritual mediation (Metcalf, 1989).

Initially, I attempted to catalogue all the creative design objects in my office, but it became a quagmire that immobilised me because there were too many leads to follow and the underlying network became too dense. So, I decided to focus on one of the objects highlighted in an exhibition: the cameo prints.

Creativity and Why It Is Important

Creativity is the ability to produce outcomes that are original and appropriate (Plucker, Beghetto, & Dow, 2004, p. 91) and can be assessed in terms of the 4P model as proposed by Rhodes (1961), where he suggests that one can evaluate creativity by examining the nature of the product, the personality of the person, the nature of the processes employed, and the relationship to the environment (press).

Of interest to me, are the role of play and the impact of serendipity on the creative process. The importance of play, regarding creativity, was emphasised by Winnicott (1989) when he stressed that "it is in play, and only in play, that the person is able to be creative and to find herself" (as cited in Creme, 2003, p. 273). For the purpose of this article, I define play as a series of connected events that provide pleasure (Eberle, 2014) and revolve around "non-serious" (Huizenga, 1970, p. 5) exploration which is "goal-directed and rule-bound" (Csikszentmihalyi, 1991, p. 71)

Serendipity is the act of finding interesting or valuable things by chance. It is a type of creativity that results from "synchronicities, fortuitous accidents . . . and fruitful detours" (Bleakley, 2004, p. 472). Johnson (2010) referred to this phenomenon as a "happy accident" and what makes it happy is the fact that the discovery is personally meaningful (p. 109). To recognise the significance of the new discovery appears to require a tolerance of ambiguity (Bleakley, 2004).

I am approaching creativity from a little-c (everyday) point of view, as opposed to a big-C (legendary) point of view (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2010). This means that I explore seemingly insignificant, but personal, everyday experiences that can be used as a resource in the creative design process. This is in reaction against how I was taught to design creatively, where there seemed to be an inordinate emphasis on Eurocentric visual references that I did not relate to, accompanied by a rigidly imposed design process with apparently no room for serendipity or play.

Skiba, Tan, Sternberg, and Grigorenko, (2010) recommended a little-c approach when addressing creativity in the classroom. Several researchers support the development of general (little-c) creativity, seeing it as our "birth right [and] survival capacity" (Richards, 2010, p. 228), "the province of every human being . . . to enhance the process of their lives" (Piirto, 2010, p. 166), and seeing it as "vital for individuals' well-being and for the well-being of our world" (Fairweather, & Cramond, 2010, p. 115). Furthermore, Torrance emphasised that teachers can contribute to the development of creative behaviour and must "build the blocks of creativity" (as cited in Baldwin, 2010, p. 86).

Exhibition of My Creative Design Process

The Transformative Education/al Studies (TES) project,1 of which I am a member, organised an exhibition that encouraged participants to display the results of their self-study and autoethnographic research by using artefacts as opposed to written texts. The exhibition was titled "The Inward I," with the aim of sharing the research with each other and with the larger academic community in Durban.

To uncover the aspects of self that are significant within the creative design process, I participated in the exhibition and focused on how lecturers could make self-reflexive research into their own educational practices more visible. For the exhibition, I produced a poster (see Image 1) that showed images of my workspace, and of the objects I was producing at that stage. I then analysed the poster and an object on the poster.

Exhibitions of this nature can be seen as a method that is used by "arts-inspired scholars" to try "seducing onlookers into encounters with their work" (Barone 2008, p. 489). In this case, the seduction was done by using shwe-shwe2 covered display boards, uniformly designed posters, and a variety of creative artefacts displayed in conjunction with the poster.

Having an exhibition can be an intensely reflexive exercise, as is made apparent by Reinikainen and Dahlkvist (2016) when they detailed the process of curating their exhibition. During curation, one has to select the appropriate artefacts and decide how to display them-all contingent on the aim, which is not always clear from the start. I have found the curation of an exhibition to be the same as the process of writing in that, similar to Hampl (1996) who writes to find out what she knows, I find out what I want to show in the process of exhibiting. I find that I become more aware of my context as creative designer when I see what I have available for showing.

Mitchell (2015b) makes it clear that exhibitions can be a useful tool for facilitating social change. Although this exhibition had social change as one of its aims, I participated because I was trying to make sense of my own creative practice and initially saw it as an opportunity for reflection. I wanted to see what I was doing. I decided to examine the artefacts that are displayed on my office walls because my office is also my design studio and workshop. I therefore produced a poster (Image 2) that showed some of the objects I had produced within the environment they were created.

This section of my poster shows the formal arrangement of the photos that depict my office as a creative space. It also shows a pair of cameo print earrings at the bottom. The following sets of images (Images 3 and 4) are the photos that were used in the poster.

The photos I decided to display were taken in my office. These showed jumbled masses of objects pinned to a notice board on one side, stacks of books and papers on my desk with some ceramic work in progress, to the side, and a range of prints, postcards, and drawings on the wall behind my computer. I decided to highlight the latest projects that I was busy with: the ceramics on my desk and the foil prints on the wall behind my computer.

The top three photos (Image 3) are oriented in a landscape format and show a type of panoramic view of my office. The lower photo shows the desk where most of my creative work happens. From this desk, the objects would migrate to the office walls. The two portrait-format photos (Image 4) show close-up views of art works. The two earring prints at the bottom of Image 2 can also be seen in the photo on the left. I paid careful attention to the layout of the photos and earrings, making sure that it was a visually pleasing arrangement.

I wanted to show the messiness of my creative space, but also show that there is some underlying structure-an order that might not be visible, but of which I was aware. When Lapum, Ruttonsha, Church, Yau, & David (2012) had an exhibition to show the intricacies of the journey a patient follows before and after surgery, they decided to use a labyrinth-like formation, because it "is symbolic of [the] patients' transition" (p. 108). To show the underlying organised structure of my seemingly messy creative space, I decided to use a formal, symmetrical, layout with a space created in the centre at the bottom for displaying a pair of earring prints. The content of the photos was chaotic-not the arrangement; and the focus, the product of the messiness, was presented as the focal point. The layout of my poster signified the underlying order of my creative process as the labyrinth, above, signified the notion of transition.

Methodology

This is a qualitative study in a transformative paradigm (Mertens, 2009), using an autoethnographic methodology to explore the aspects of self that play a role in my creative practice.

Ellis (2004) and Holman Jones (2005) provided a very clear definition of what autoethnography is: "Autoethnography is an approach to research and writing that seeks to describe and systematically analyze . . . personal experience . . . in order to understand cultural experience" (as cited in Ellis, Adams, & Bochner, 2011). The diverse nature of our educational settings leads to unexpected outcomes, and Mitchell (2015a) recommended an autoethnographic approach for university educators who seek to "locate and make sense of our experiences" (p. 10), with the aim of contributing to social change.

Autoethnographic self-interview and multivocality

When I tried to explore the creative artefact, I did not know how to proceed. To overcome the writer's block, I attempted to start writing by focusing on initial observations and rememberings. After I had jotted these down, I started responding to these prompts.

Reflecting on my responses, I realised I had adopted two distinctly different voices: that of an autoethnographic interviewer, and that of an autoethnographic informant. I had, in fact, conducted a semi-structured interview with myself. This relates to Anderson and Glass-Coffin's (2013) definition of an autoethnographic self-interview as "involv[ing] dialogue between one's past and present selves" (p. 69), and is similar to Mizzi's (2010) notion of multivocality, which states that there are "plural and sometimes contradictory narrative voices located within the researcher" that would "expand the ways we can perceive and inquire into an encounter" (p. M3).

My self-interview was different from the types of self-interviews that Keightly, Pickering, and Allet (2012), Singh (2012), and Meskin, Singh, and van der Walt (2014) conducted. Keightly et al. (2012) had a group of research participants who were given questions and audio recording devices so that the participants could interview themselves. The benefit was that the interviews could be paused and resumed as required or determined by conditions.

Singh (2012) examined her own life story as educator and used a set of prepared questions to keep her focused on what Webster and Mertova (2007) called "critical events" (as cited in Singh, 2012, p. 86). She deliberately selected "people, events and places" she felt contributed to the development of her "educational persona" (p. 86), and then responded to these questions in writing.

Meskin et al. (2014) wished to examine their own professional practice. To do this they drew up a list of predetermined questions, which were reviewed by a critical friend, to have asked of themselves by this critical friend. They therefore named their method a reciprocal self-interview (RSI).

Riggins (1994) classified the content of responses that an interviewer obtains from an informant in two ways: referencing (denotative) or mapping (connotative). Referencing responses are the kind where the information provided concerns "the history, aesthetic or customary uses of an object" (p. 109), whereas mapping responses indicate the extent to which objects are representations of the social world, the ideology, of the informant. My responses started as denotative and then became more personal and connotative. Not all the responses became connotative but where they did, I became aware of nuances and influences that were not apparent on the first inspection or reflection. This is similar to the first-second draft writing that Hampl (1996) does, where the first draft is a remembering and the second draft is a re-remembering of the same memory (Strong-Wilson, Mitchell, Allnutt, & Pithouse-Morgan, 2013), except that my drafts are combined-with impressions and feelings added to the second draft as they arise.

Analysis

I analysed my self-interview by treating it as a narrative (Riessman, 2008). On examining the narrative for patterns that make sense (Bernard, 2011), I realised that the information I had provided could be divided into the two categories that Riggins (1994) used when analysing material artefacts, that is, referencing (denotative) and mapping (connotative). The prompts used by me as autoethnographic interviewer self were denotative and the responses by me as the autoethnographic informant self were connotative. On coding the responses, I noticed areas where the connotative information revealed aspects of the self and other areas that caused insights and realisations-sometimes with pedagogical implications. I also became aware of more voices that could be called on to comment. These are voices that show my playful self, my consumerist self, my stereotypical male self, and my lecturer self, to name some of them.

The autoethnographic interviewer self's denotative prompts that I developed, and that are responded to in the next section, are as follows:

• Where I initially encountered gold foil or leaf

• Embossing

• The champagne and chocolate wrapper foil

• The red string

• The handmade paper

• The message, and its origin.

The aspects of self that were revealed are discussed under Discoveries at the end of the article, and the insights are noted within text boxes below the responses that evoked them. This is a method of noting that I have used before (de Beer, 2016), and which helped to show the meta-narrative as it unfolded.

Trustworthiness

In autoethnography, issues of reliability and validity are linked (Ellis, Adams, & Bochner, 2011). According to Ellis, Adams, and Bochner, reliability is contingent on credibility; I have, therefore, outlined the process I followed exactly as I experienced it. By making my processes of writing and interrogation of the writing visible in the way that I do, I believe that I adhere to Mishler's (1990) point of view regarding the validity of inquiry-guided research. He insisted that the "visibility of the work" (p. 429) increases the trustworthiness. I've done this by including images of the objects I examined, and images of the examples I referred to, where available. Some of these images, being artworks, have their dates of origin inscribed on them. To promote trustworthiness further, I have stated the relationship between my creative design work and my occupation.

The Cameo Print Earrings: Responding to the Prompts

Image 5 shows one of a pair of earrings that is displayed as a print. It is a small sheet of handmade cotton paper that has been folded in half, with a rectangle of gold-coloured foil folded over it. It has an image of a classical cameo profile stamped onto it in silver metallic foil, with an embossed fleur-de-lis medal top, above it. To be worn as an earring, it can be suspended from the red thread tied through a grommet that has been inserted near the top in the middle.

I present my autoethnographic informant-self's connotative responses to each of the prompts:

Where I initially encountered gold foil or leaf

The first time I saw gold leaf work in real life, I was amazed. It was a print that was done by my lecturer at that time, Dieter Dill, and I happened across it at an exhibition in George. I couldn't understand how it was done, and I think that was part of the magic of the experience.

When I researched how gold leaf was done, it turned out to be a laborious technique that needed a lot of preparation and careful work. I did try it over the years but never really succeeded. I then saw

the technique a few years later and it reignited the flame . . . I tried gold paint and various other techniques to imitate it but still did not manage.

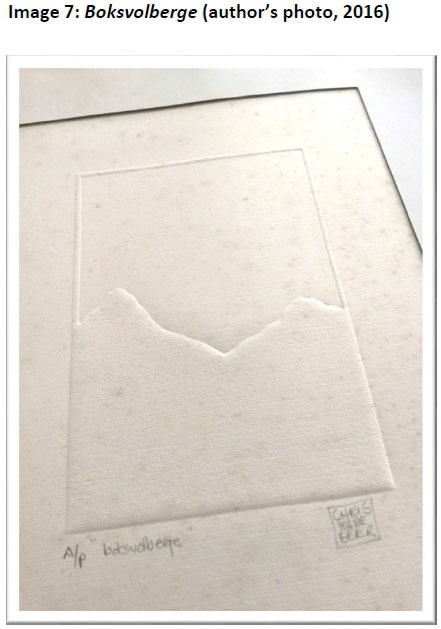

When I recently went to Haesloop, a supplier of fashion accessories, I saw, incidentally (serendipitously), that they sold rolls of metallic foils for hot stamping. This is the contemporary technique used to stamp gold lettering on the spine of leather-bound books. When I enquired, they said it was applied using heat, about 100 degrees centigrade. I was given some samples to try out and I experimented that evening, using an electric clothes iron. I remember it was a metallic blue foil I tried first, and I was stunned by the beauty of the foil print (I think it was a bit like the magic I mentioned earlier). I just made some crosses and dragonfly shapes (Image 6), and it worked well enough for me trealise that I had encountered a new vein of creative work to mine.

Embossing

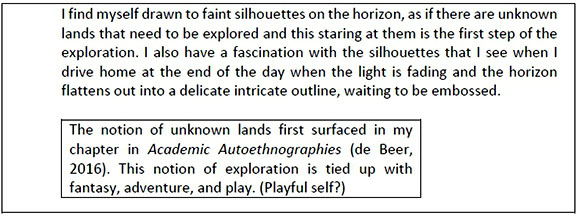

I first embossed a print when I was an undergraduate student at Stellenbosch in 1984. One of the modules I did was printmaking and I was taught traditional printmaking, such as hard and soft ground etching. A project I had to do then was called boksvolberge [box full of mountains]. I initially tried to depict mountains by drawing them, but gave up because the paper was too small to depict a mountain, or so I thought.

The mountains in the Western Cape are often seen as silhouettes in the distance, and it was this aspect I was fascinated by-the way that mountains are seen as layers of ever diminishing, overlapping, and pale blue-grey shapes. I tried to capture this by cutting out the shape of a mountain and then embossing the background into the paper, which raised the profile of the mountain in relief (see Image 7-and note the date in the signature: '84).

Because an embossing is done without colour, one has to see the print in the type of light that will show the relief; it therefore becomes quite subtle and like the faint silhouettes that one sees on the horizon. When embossing is done on handmade paper, it is even more effective because the difference between the rough, natural texture of the paper is contrasted with the smooth, pressed surface of the embossed area.

Champagne and chocolate wrapper foil

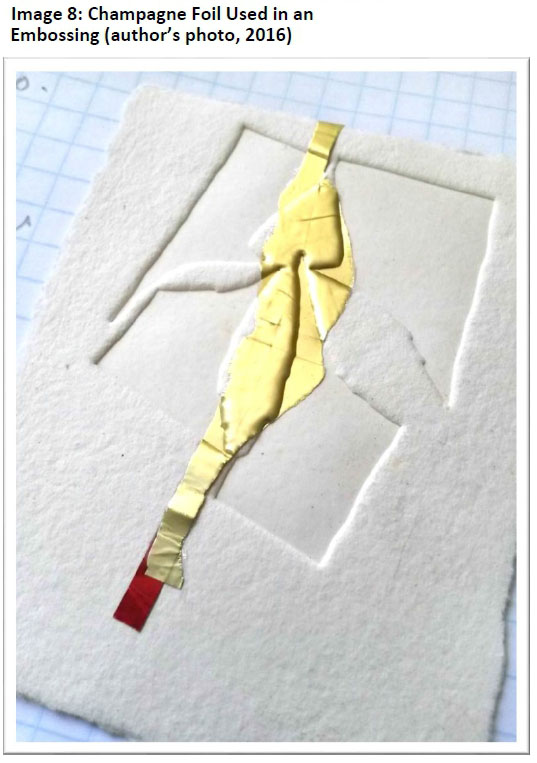

At a staff exhibition in 2009, I saw two artworks by a colleague that made quite an impression on me. The works were rather large (700 mm x 700 mm) and used curly burglar bar designs as the main motif. What intrigued me were the backgrounds-one was metallic silver and the other metallic gold. The silver turned out to be the silver foil from cigarette boxes and the other was gold foil from champagne bottles.

As soon as I recognised the origin of the foil, I realised that I had a source of such gold foil at home because we regularly opened a bottle of champagne and simply threw the foil away; this was an opportunity to turn a routine into a ritual. Every time I opened a bottle of champagne, I was generating raw materials for creative practice. I started keeping the foils religiously (ritually?) and also kept the bit of foil that had the little red tab one uses to tear the foil open, because I realised that the red tab had its own aesthetic possibilities. The piece of foil that is torn off sometimes, serendipitously, resembles a human figure, and the red tip at the bottom could be seen to allude to blood and the notion of opening, of tearing open. Image 8 shows one such torn-off tab used in an embossing.

I did make some prints where I combined the metallic foils with the champagne foil, but the champagne foil started looking a bit insipid to me. It was as if it was 9-carat gold compared to 18-carat. It did not have the lusciousness of pure gold; it looked watered down.

At more or less the same time as the champagne routine, there was a chocolate routine. It was customary to have a small piece of chocolate for dessert in front of the television, after a small whiskey and before bedtime. I was given a box of Ferrero Rocher chocolates one Christmas at about that time, and noticed the beautiful gold-coloured foil. It looked like 18-carat gold compared to the champagne foils (luscious!). I applied the hot stamping metallic foil on top of this chocolate wrapper and it was beautiful! The chocolate wrappers were now removed and stored very carefully to keep them intact and, for a while, the chocolate opening routine had a ritualistic feel to it.

Red string

The red string I use is embroidery cotton and initially, to me, this particular shade of red only had the connotation of blood. It acquired another connotation when an ex-student of mine, who is Hindu, sent me my first Lakshmi string in 2001. A Lakshmi string is the red string that Hindus tie around their wrists as a sign of devotion to Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of wealth, fortune, and prosperity. I receive one of these strings every year and am assured that it has been blessed by the local Hindu priest. When I use red string now, it has a psychological richness that I do not try to explain, I just feel that it is significant.

Handmade paper

I like the idea of making one's own paper. It is a material that we take for granted and discard very easily. I am sure that, were we to make our own paper, we would be more careful with it. One can buy handmade paper, and it is usually a bit thicker than mass-produced commercial paper and the colour is also creamier because it has not been bleached. The kind of handmade paper I use is made for watercolour painting or printmaking, and it is made from cotton, often recycled cotton cloth. It is available with a smooth or a rough texture, and I prefer the rough texture.

I discovered that there is a paper making unit in my department and have been given some sheets of handmade paper. I have also made a few sheets of my own, which I used for the cameo print earring that is explored here. Handmade paper is recognised by the edge, which is kind of ragged and known as a deckle edge. The deckle is the frame that traps the paper fibres on top of the sieve. It looks almost like a torn edge, and has convinced me to tear my paper to size rather than cut it. See Image 9 for a comparison of the deckle edge with the torn edge. The deckle edge is on the left and the torn edge on the right.

I now arrive at the size of my prints by tearing the large sheets of handmade paper in half, and in half again, until they are about A6 in size. A6 is an A4 sheet of paper divided into quarters, or folded in half twice. I think it is because as a jeweller, I make relatively small things-things that fit inside my cupped hands-that I feel comfortable with such small prints. Even when inspecting a large object or print, I always inspect it closely and notice all the surface textures and details, looking for traces of how it was made.

A friend recently gave me a stack of handmade paper that had belonged to his late father, a well-known artist. I've realised that the significance of the materials I use can extend beyond how they are produced to where they come from or are found, and could add to the story of the work that I produce.

The message, and its origin

The cameo print earrings I show here are part of a series of prints called "Medals for Women." Being in a relationship with a woman, I have become acutely aware of the trials and tribulations women have to go through, often without any acknowledgement. I wanted to demonstrate my awareness of, and involvement in, this issue without laying claim to the right to bestow these awards.

"Medals for Women" are not actually medals, they are a manifestation and acknowledgement of my awareness. I use many traditional heraldic devices and motifs to make these prints look like medals, particularly the ribbons from which the medals hang, the bar at the top, and the connection between the medal and the ribbon. I found that the fleur-de-lis motif could be interpreted in various subversive ways: it could be a lily but also a spear.

The fact that I use a classical cameo profile probably refers to the stereotypical roles of women. I did make a personalised profile of my partner, but felt that it was too personal, as if I was bestowing a medal on her. It could too easily be interpreted as me being patronising, so I kept the profile anonymous.

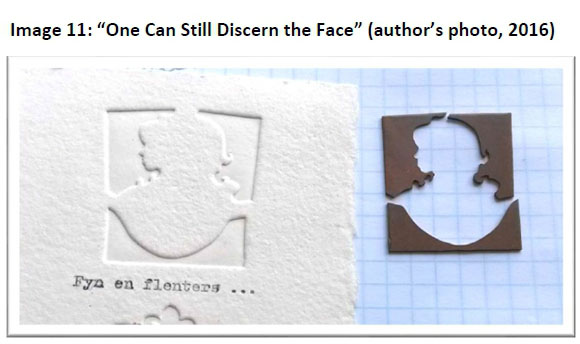

The cameo profile, and its surrounding pieces (Image 11), that I do use for the embossing was obtained from a colleague's scrap box. She had cut it out but was not going to use it, so I rescued it before it was disposed of. Another happy accident.

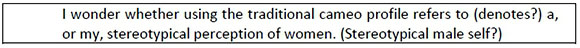

These two prints were done in the format of earrings. They allude to being wearable in terms of their size and the fact that there is a connection and a loop at the top. A further suggestion of them being earrings is the fact that they are a pair, not identical, but there is a definite relationship between them: they are opposites, in a way. One does have to examine the prints a bit closer to notice this, but they are inverted: in one print, the face is silver and in the other print the space surrounding the face is silver (see Image 10, cropped from the original display image, which explains the lack of crispness). It does refer to the act of perception. Are we aware of a thing or of the space around the thing? Are people defined by what we see when we look at them, or by what surrounds them?

Discoveries

Having identified various aspects of self that play a role in my creative design process, and considering these in relation to how I perceive my creative design process to unfold, I realised that the process is not linear, serendipity can be harnessed, play is important, and personal experiences can be useful as references for the creative design process.

The creative process is not linear

Sawyer (2010, p. 182) confirmed that "creativity takes place over time" and is not limited to the moment of inspiration. When I trace some of the developments in the creative design process of the cameo print, I notice that, in some cases, a number of years have gone by since the first encounter with a phenomenon, such as a new material or process, and when it was actually implemented. The most significant example here would be the long association I have with gold leaf. I first noticed it as a student at an exhibition in which my lecturer was participating in about 1985, and have had intermittent encounters with it and its stimulants since then. The most recent incident occurred when I serendipitously discovered it at a supplier of fashion accessories and started using it in my "Medals for Women" range of prints.

Another element that shows the iterative cyclical nature of the creative design process is my use of the red string. Over the years, it has become more significant to me due to the nature of my interpersonal relationship with an ex-student, and the way I used it in other works of art.

Serendipity allows the creative process to flow

Mitchell (2016) discussed autoethnography as a wide-angle lens with which we, as university educators, can examine the world through ourselves. She touched on how serendipity affords us an opportunity to examine just what it is we value and what our preconceptions are. My own preconceived ideas about how the world ought to be, how the design process should work, and what it actually means to be creative have been exposed in several instances where serendipitous discoveries and encounters allowed my creative process to flow and then result in unexpected but desirable outcomes. The gold foil and chocolate wrappers are examples of how my creative process progressed after these fortuitous discoveries provided new connections, or solutions, for design problems that I had been incubating subconsciously.

I realise now that the same quagmire (my seemingly chaotic office) that hampered my analysis can be seen as an environment that is conducive to serendipitous discoveries taking place.

Elements of play are requirements of the creative process

There are several instances where I recognise aspects of play entering my creative process. The aspects that I particularly notice are curiosity, discovery, delight in exploring, development of seemingly unrelated skills, and feelings of contentment after a bout of such playful activity. This playfulness is most apparent when I produce a number of prototypes by just trying new techniques or when I stare at the horizon, daydreaming and wondering what adventures might be there. Richards (2010) emphasised the importance of play and describes it as the "one way that we truly-and delightfully- learn" (p. 220). I also recognise elements of play when I think divergently and tolerate ambiguity, which are both requirements of the creative process (Torrance, as cited in Sternberg, 2006, p. 87).

Personal experience provides resources and impetus for the creative process

Lowes showed the importance and relevance of personal experience within the creative process in his model of "well" and "will." The well is described as a "dedicated form of gathering and coagulation of life experience," and the will as "the re-ordering of this often chaotic material" (as cited in Bleakley, 2004, p. 470).

The personal experiences that are prominent in this autoethnography, and that fill my own well are my interpersonal relationships, the materials I encounter, and my physical environment. The will or reordering processes I employ have been developed over the last 30 years and it is unfair to expect my students to be as fluent in their reordering (or design processes) when they have barely left school.

Pedagogical Implications

The discoveries I made regarding my own creative design process all have implications for the adjustment of my pedagogical practice.

The creative process is not linear

I have become more mindful that I should not assess my students' creative outputs based on work that is produced over a relatively short period of time. They will probably only produce their notable work a few years after they have left the department. Several researchers claim that it takes at least 10 years, or 10,000 hours, of practice before one can be truly creative (Baer & Garrett, 2010). If I could get my students to document and reflect on their creative work over an extended period of time, it might make the development of their creativity more evident and encourage their willingness to explore and venture into new and uncertain areas.

Serendipity plays an important role in the creative process

It is possible to create environments that are conducive for serendipity to take place. This would entail providing numerous influences, both visual and conceptual, for new connections to be made. The visual influences could take the form of images and objects, and the conceptual influences could be provided by encouraging dialogue in the form of reflections and conversations.

I often notice serendipitous occurrences in the work my students do. These usually take the form of accidents or mistakes where the outcome is not what they had in mind or, more often, not what they think I had in mind. It could be useful to have conversations regarding their mistakes as part of the assessments that are done.

Elements of play are requirements of the creative process

In a jewellery design programme, the emphasis is on the establishment of a product, a piece of jewellery. By moving the emphasis of the creative design process away from the product, a space might open for play to be encouraged. This could be done by focusing on the design process that precedes the making of the final object-the stage where a number of potentially useful ideas are generated, based on personally meaningful resources, and the prototypes are produced.

The format in which ideas and prototypes are developed could range from loose pencil drawings, to water colour sketches, to paper cut outs, to 3-dimensional wire "drawings," to ceramic models, and rough "jewels" made from copper and brass. These are all approaches that would decrease the anxiety that accompanies working in expensive precious metals.

Playful engagement in this phase would result in numerous connections that could lead to serendipitous discoveries at a later stage. It would also lead to diverse solutions to the same problem, particularly if it is done collaboratively.

Personal experience provides resources and impetus for the creative process

I have realised that I could encourage my students to "gather and coagulate" (Lowes, as cited in Bleakley, 2004, p. 470) more deliberately. The gathering would be a matter of using journals, in various forms, to document the various influences that surround them. Examples of such influences could be images of artefacts that are in their personal spaces, and visual or written documentation of experiences such as celebrations and excursions. Coagulation would constitute the use and manipulation of such gathered material in the execution of a specified project brief.

Conclusion

This exploration was aimed at gaining an understanding of my creative design process so that I can facilitate the development of my students' creativity in the jewellery design class. The methodology I employed facilitated such an investigation, where I used my various autoethnographic voices to gain access to the deeper layers of significance that manifest via my creative artefacts. I realise that autoethnography is a most suitable methodology to use when trying to uncover the various aspects and influences that contribute to my creative design process, particularly when I employ self-interviews and "multivocality" (Mizzi, 2010) to identify and isolate the various selves at work.

The pedagogical implications that I have identified, while apparently simple, like "keep a journal," are much more complex than they seem, as I have already started discovering. I think I have slowly realised that I am able to create my own meaning by engaging with the world around me with a sense of curiosity. There are interesting and useful things all round us, if we can just acknowledge them. Once they are acknowledged they become part of our mental library and we can draw on them as required. That is what I sense when I look at my office walls-all the seemingly mundane things that become interesting when used in a different context.

As Mitchell (2015a, p.11) highlighted, autoethnographic research by university educators can contribute to social change by making visible "the richness of the diversity of our classrooms" as an vital resource for "identifying the moments of learning (about ourselves and our students)." I think that my students often underestimate the value of their personal histories and stories as far as using these as references to draw on when working on projects in design class, or when solving problems creatively. What I mean is, I think everybody has within them interesting ways of doing and seeing things that would facilitate their being creative in a useful way. It is just that we can be so overwhelmed by the world, and its hegemonies, that we can feel inadequate. I want to encourage my students to use their innate curiosity and to engage creatively with the world around them using their own personal experiences as a foundation and reference for creative work. This could involve using local and indigenous resources that are personally significant, rather than colonial or Eurocentric references.

References

Anderson, L., & Glass-Coffin, B. (2013). I learn by going: Autoethnographic modes of enquiry. In S. Holman Jones, T. E. Adams, & C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of autoethnography (pp. 57-83). Walnut Creek, USA: Left Coast Press. [ Links ]

Baer, J., & Garrett, T. (2010). Teaching for creativity in an era of content standards and accountability. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity In the classroom (pp. 6-23). Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Baldwin, A. Y. (2010). Creativity: A look outside the box in classrooms. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (pp. 73-87). Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Barone, T. (2008). Going public with arts-inspired social research: Issues of audience. In J. G. Knowles & A. L. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 485-491). Thousand Oaks, USA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2010). Broadening conceptions of creativity in the classroom. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (pp. 191-205). Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Bernard, H. R. (2011). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (5th ed.). Plymouth, UK: Altamira. [ Links ]

Bleakley, A. (2004). 'Your creativity or mine?': A typology of creativities in higher education and the value of a pluralistic approach. Teaching in Higher Education, 9(4), 463-475. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1356251042000252390 [ Links ]

Creme, P. (2010). Why can't we allow students to be more creative? Teaching in Higher Education, 8(2), 273-277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1356251032000052492 [ Links ]

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, USA: Harper Collins. [ Links ]

De Beer, C. (2016). Creative self-awareness: Conversation, reflections and realisations. In D. Pillay, I. Naicker, & K. Pithouse-Morgan (Eds.), Academic autoethnographies: Inside teaching in higher education (pp. 49-68). Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense. [ Links ]

Eberle, S. G. (2014). The elements of play: Toward a philosophy and a definition of play. The American Journal of Play, 6(2), 214-233. [ Links ]

Ellis, C., Adams, T. E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Art. 10. Retrieved from http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1101108 [ Links ]

Fairweather, E., & Cramond, B. (2010). Infusing creative and critical thinking into the curriculum together. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufmann (Eds.), Nurturing creativity In the classroom (pp. 113141). New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hampl, P. (1996). Memory and imagination. In J. McConkey (Ed.), The anatomy of memory (pp. 129139) New York, USA: Oxford University Press [ Links ]

Harrison, L., Pithouse-Morgan, K., Conolly, J., & Meyiwa, T. (2012). Learning from the first year of the Transformative Education/al Studies (TES) project. Alternation, 19(2), 12-37. Retrieved from http://alternation.ukzn.ac.za/docs/19.2702%20Har.pdf [ Links ]

Holman Jones, S., Adams, T. E., & Ellis, C. (Eds.). (2013). Handbook of autoethnography. Walnut Creek, USA: Left Coast Press [ Links ]

Huizenga, J. (1970). Homo ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. London, UK: Paladin. [ Links ]

Johnson, S. (2010). Where good ideas come from: The natural history of innovation. New York, USA: Riverhead. [ Links ]

Keightly, E., Pickering, M., & Allet, N. (2012). The self-interview: A new method in social science research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 15(6), 507-521 [ Links ]

Lapum, J., Ruttonsha, P., Church, K., Yau, T., & David, A. M. (2012). Employing the arts in research as an analytical tool and dissemination method: Interpreting experience through the aesthetic. Qualitative Enquiry, 18(1), 100-115. [ Links ]

Mertens, D. M. (2009). Transformative research and evaluation. New York, USA: Guilford Press [ Links ]

Meskin, T., Singh, L., & van der Walt, T. (2014). Putting the self in the hot seat: Enacting reflexivity through dramatic strategies. Educational Research for Social Change, 3(2), 5-20. [ Links ]

Metcalf, B. (1989). On the nature of jewelry. Retrieved from http://www.brucemetcalf.com/pages/essays/naturejewelry.html

Mishler, E. G. (1990). Validation in inquiry guided research: The role of exemplars in narrative studies. Harvard Educational Review, 60(4), 415-442. [ Links ]

Mitchell, C. (2015a). Hopefulness and suspense in the autoethnographic encounters of teaching in higher education. Journal of Education, 62, 7-12. [ Links ]

Mitchell, C. (2015b). Looking at showing: On the politics and pedagogy of exhibiting in community-based research and work with policy makers. Educational Research for Social Change, 4(2), 48-60. [ Links ]

Mitchell, C. (2016). Autoethnography as a wide-angle lens on looking (inward and outward): What difference can this make to our teaching? In D. Pillay, I. Naicker, & K. Pithouse-Morgan (Eds.), Academic autoethnographies: Inside teaching in higher education (pp. 175-190). Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense. [ Links ]

Mizzi, R. (2010). Unraveling research subjectivity through multivocality in autoethnography. Journal of Research Practice, 6(1), M3. Retrieved from http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/201/185 [ Links ]

Piirto, J. (2010). The five core attitudes, seven I's, and general concepts of the creative process. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (pp. 142-171). Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Plucker, J. A., Beghetto, R. A., & Dow, G. T. (2004). Why isn't creativity more important to educational psychologists? Potentials, pitfalls, and future directions in creativity research. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), 83-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep39021 [ Links ]

Quickenden, K. (2000). Virtual gallery of contemporary jewellery: Introduction [CD-ROM]. [ Links ] Birmingham, UK: Birmingham Institute of Art and Design.

Reinikainen, L., & Dahlkvist, H. Z. (2016). Curating an exhibition in a university setting. In D. Pillay, I. Naicker, & K. Pithouse-Morgan (Eds.), Academic autoethnographies: Inside teaching in higher education (pp. 69-83). Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense. [ Links ]

Rhodes, M. (1961). An analysis of creativity. Phi Delta Kappan, 42(7), 305-310. [ Links ]

Richards, R. (2010). Everyday creativity in the classroom. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (pp. 206-234). Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Los Angeles, USA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Riggins, S. H. (1994). Fieldwork in the living room: An autoethnographic essay. In S. H. Riggins (Ed.J, The socialness of things: Essays on the socio-semiotics of objects (pp. 101-148). Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Sawyer, R. K. (2010). Learning for creativity. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.),Nurturing creativity in the classroom (pp. 172-190). Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Singh, L. (2012). Strutting and fretting, a drama education retrospective. Journal of Education, 54, 85102. [ Links ]

Skiba, T., Tan, M., Sternberg, R. J., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2010). Roads not taken, new roads to take. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (pp. 252-269). Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Sternberg, R. J. (2006). The nature of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 18(1), 87-98. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1207/s15326934crj180110 [ Links ]

Strong-Wilson, T., Mitchell, C., Allnutt, S., & Pithouse-Morgan, K. (2013). Productive remembering and social action. In T. Strong-Wilson, C. Mitchell, S. Allnutt, & K. Pithouse-Morgan (Eds.), Productive remembering and social agency (pp. 1-16). Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense. [ Links ]

1 TES is a collaborative project that involves about 40 participants from a range of diverse academic and professional contexts. The group meets twice a year for inter-institutional workshops. Smaller groups meet weekly or monthly at various participating universities. The main research question that guides the self-study activities revolves around transforming one's educational practice. The project supports and investigates the collaborative self-reflexive activities of the project members (Harrison, Pithouse-Morgan, Conolly, & Meyiwa, 2012).

2 Shwe-shwe (see the background of the display board in Image 1) is a printed cotton fabric that is available from textile shops in Durban. It was traditionally used by Sotho and Xhosa women, but is now widely used by all cultural groups.