Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Educational Research for Social Change

On-line version ISSN 2221-4070

Educ. res. soc. change vol.5 n.2 Port Elizabeth Sep. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2016/v5i2a2

ARTICLES

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2016/v5i2a2

Collaborated understandings of context-specific psychosocial challenges facing South African school learners: a participatory approach

Rubina SetlhareI; Lesley WoodII; Lukas MeyerII

IUniversity of Johannesburg rubinasm@uj.ac.za

IINorth West University

ABSTRACT

South African teachers are not sufficiently equipped to address psychosocial challenges that they encounter in under-resourced contexts among learners at school, and which impact negatively on learning and teaching. In this article, we report on the first cycle of a community-based participatory action research project undertaken with teacher participants to facilitate a collaborative understanding of the contextual psychosocial challenges that learners face. The aim of the study was to equip teachers with sustainable capacity to conduct a participatory action learning and action research (PALAR) enquiry that would enhance their ability to identify and address contextual psychosocial challenges to promote wellness. Following a PALAR design, we collaborated with 10 volunteer teachers for the generation of qualitative data through relationship building activities, individual interviews, the creation of visual artefacts, and informal group discussions. Data were analysed thematically in collaboration with the community of participants. Findings suggest that the process assisted the teachers to gain a deeper understanding of learners' psychosocial challenges, encouraged a sense of group identity among coresearchers, and fostered their agency to begin to address the identified challenges and to network with community stakeholders to promote wellness among themselves and among learners.

Keywords: Action research, community-based partnerships, learner wellness, psychosocial challenges, South African schools, under-resourced communities

Introduction

Learners at under-resourced schools in South Africa face significant psychosocial challenges (Spaull, 2013) that negatively affect both their own wellness and that of the teachers, ultimately resulting in a lower quality of teaching and learning (Modisaotsile, 2012). The transition from a segregated apartheid education system, where resources were inequitably allocated according to race (Modisaotsile, 2012), to an inclusive education system has been fraught with challenges. Inequitable access to resources (Bruce, 2014; Spaull, 2013) and sectored poverty (Donald, Lazarus, & Lolwana, 2010) continue to play a role in contributing to the psychosocial challenges faced in South African under-resourced communities, which consequently affect the wellness of members of the school community in that context (Donald et al., 2010). Contextual challenges relevant to this article include poor living conditions in informal settlements with little access to basic amenities (Donald et al., 2010), poor parenting (Ward et al., 2014), poverty-related HIV/AIDS issues (Theron, 2009), socioeconomic influences on teenage sexuality (Miller et al., 2014), substance abuse (Tlale & Dreyer, 2013), school violence (Mampane, Ebersöhn, Cherrington, & Moen, 2014), and poor parent participation within school structures (Joubert, Ebersöhn, Ferreira, du Plessis, & Moen 2014; Khanare, 2012; Mncube, 2009). South African school teachers are inadequately prepared to support learners within such contexts (Masitsa, 2011; Motshekga, 2010), having only received very basic concepts of educational psychology and community development as part of their preservice training (Donald et al., 2010). This situation negatively impacts on the wellness of the individual teacher and on the larger school system. While workshops are conducted sporadically to improve the support skills of in-service teachers, these are inadequate for capacitating teachers to support learners in under-resourced urban black communities (Motshekga, 2010), commonly known in South Africa as townships.

Inadequately prepared teachers are understandably anxious and overwhelmed by the complex challenges experienced by their learners (Masitsa, 2011; Modisaotsile, 2012), making it difficult for them to mobilise their potential agency (Freire, 1970/2005). An asset-based paradigm (McKnight & Kretzmann, 1993; Pillay, 2012) suggests that teachers possess the potential and willingness to support vulnerable learners if they are equipped with the knowledge and skills to do this (Hoadley, 2007; Malindi & Machenjedze, 2012; Mampane & Bouwer, 2006; Theron, 2009). In this article, the authors suggest that a participatory action learning and action research (PALAR, Zuber-Skerritt, 2012) process would be suitable to improve the capacity of participating teachers to support learners and thereby feel less overwhelmed and anxious. PALAR (Zuber-Skerritt, 2011) aims to improve professional practice and involves an iterative and collaborative process that allows professionals to iteratively and collaboratively reflect on their actions throughout the cyclic PALAR process (Zuber-Skerritt, 2012). By following the PALAR process as expanded on in the section on PALAR as a theoretical paradigm, teacher participants collaborated with each other to come to a better understanding of the psychosocial challenges faced by learners. The aim of this PALAR project was not merely for identifying contextual wellness challenges at school level, but also to add to existing indigenous knowledge (Kearney & Zuber-Skerritt, 2012) with regard to how such contextual issues could be addressed (Zuber-Skerritt & Teare, 2013) to enhance wellness. Indigenous knowledge refers to existing systems or strategies "generated in a communal way and based on the experiences of a specific group of people" (Fasokun, Katahoire, & Oduaran, 2005, p. 61), which communities follow when identifying and addressing contextual challenges as a collective (Teare & Zuber-Skerritt, 2013).

Some background to the current PALAR project is presented before explaining PALAR theoretical assumptions. The methods used to facilitate the generation of knowledge by participants is explained, including the ethical considerations and measures to ensure trustworthiness. After critical discussion of the findings in relation to relevant literature, the authors conclude by discussing the relevance of findings for the promotion of psychosocial wellness in South African township schools.

Context and Background

The facilitator of the PALAR process was guided by her academic promoters, the coauthors of the article, throughout this project. The facilitator is a registered educational psychologist and lecturer in educational psychology at an institution of higher education. She volunteered at an under-resourced township school in a peri-urban setting in the North West Province, South Africa, to offer therapeutic services to individual educators and learners as a form of community engagement. The school had 1,009 learners and 36 teachers with varying teaching experience and from differing cultural backgrounds, with few effective psychosocial support structures in place. The African learners from different ethnic groups who came to her for therapy, presented with challenges stemming from harsh socioeconomic realities, reflecting a complex web of adversity. Teachers also sought individual therapy for themselves related to financial problems, work-related stress, trauma, HIV and AIDS, grief, and relationship problems. Teachers who accessed the therapeutic service specifically requested assistance for them to support learners with psychosocial challenges. The facilitator observed that these teachers were committed to supporting the learners, but tended to do so from their personal resources, which placed extra financial and psychological pressure on them and their families. In response to the teachers' request for assistance, the facilitator consulted with her academic advisors. They suggested a process to support these teachers in their effort to promote sustainable school wellness (Myers & Sweeney, 2008) by adhering to the 7Cs of PALAR (Zuber-Skerritt, 2011). The PALAR process (Zuber-Skerritt, 2012) aimed at developing teacher competence through collaborative communication in groups, where they supportively coach one another and commit to a process of critical reflection on their actions (Zuber-Skerritt, 2011). By following iterative cycles of reflection and action, the participants can develop character-by being open to new perspectives, opportunities, and innovations. They learn to be action leaders (Zuber-Skerritt, 2011) capable of addressing the psychosocial challenges facing learners in a sustainable and systematic way, rather than repeatedly responding piecemeal to individual learner needs. The following research question was formulated, based on the project aims as expressed by the teacher participants for this first cycle of the PALAR project, as verified by the participating teachers: "How could the PALAR process help teachers come to a collaborative understanding of the psychosocial challenges their learners face, as a first step in helping them access support for those learners?"

Participatory Action Learning and Action Research as a Theoretical Paradigm

The PALAR process aims at collaborative transformation and empowerment of community members (Zuber-Skerritt & Teare, 2013) by allowing their knowledgeable voices to be heard (Kearney, Wood, & Zuber-Skerritt, 2013), thus acknowledging existing indigenous knowledge and skills (Zuber-Skerritt & Teare, 2013). Learning occurs through an iterative process of action and critical reflection (Kearney et al., 2013) that encourages participants to reflect on their professional practice, both individually and collaboratively, to improve their educational circumstances, while encouraging democratic, mutually rewarding partnerships in keeping with the 7Cs of PALAR (Zuber-Skerritt, 2011). The aim is to promote transformative action, character building of individual participants and the community, while simultaneously contributing to professional theory and practice (Zuber-Skerritt, 2011). A critical attitude promotes knowledge creation through experiential learning (Kolb, 2014) in order to solve real-life problems (Zuber-Skerritt & Teare, 2013). Participants communicate as collaborative coresearchers and distributors of knowledge when they exercise their personal and collective agency for addressing challenges in their community (Stringer, 2013; Teare, 2013). The knowledge generated is then ploughed back into the context for further action and reflection (Herr & Anderson, 2005). Just as adversity develops within a context, so reflexive responses need to be contextually and collaboratively designed by those familiar with that context (Chilisa, 2005). Therein lies the uniqueness of the PALAR process, which allows participants who were excluded within traditional researcher-driven interventions to participate in empirically sound research. This is a liberating and transformative shift from traditional research where the researcher is the expert (Chilisa, 2005) who aims to establish objective truth (Mertens, 2010; Minkler, 2005; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003) to suggest valid solutions across all contexts. PALAR seeks to acknowledge and evolve traditional empirical research to integrate with local knowledge (Fasokun et al., 2005; Teare, 2013) to benefit the community and to simultaneously generate action as well as empirically sound theory. The three processes mentioned below (Kearney et al., 2013) are an integral part of any PALAR project from the outset, facilitated by the embodiment of the principles summarised as the 7Cs, mentioned above:

• Development of democratic, authentic, trusting, and supportive relationships.

• Regular personal and group reflection within the collaborative learning environment.

• Recognition of the achievements of all participants.

Figure 1, based on Zuber-Skerritt's design for an action learning and action research project (Zuber-Skerritt & Perry, 2002), illustrates the process followed by the participants to come to a collaborative understanding of the contextual psychosocial challenges faced by learners:

The PALAR Process as Methodology

The facilitator and teachers who had initially requested support presented the proposed PALAR project to the entire school staff with the permission of the principal. Five female and five male teachers from diverse local cultural backgrounds and of ages varying between 40 and 60 years, and with varying professional training and experience, volunteered to participate. These participants democratically agreed on weekly meetings at a time that was most convenient.

This first cycle of the PALAR process, as depicted in Figure 1, was completed over 8 months in 18 sessions. Sessions and activities were video recorded and later transcribed. Commitments such as sport events, union meetings, staff meetings, family responsibility, and personal illness often meant that attendance by participating teachers was irregular. This became a significant challenge to progress and participants collaboratively agreed that the weekly meetings would go ahead even when all participants could not attend, so as not to lose momentum. At times, only one participant attended the planned session. Parallel to the relationship building activities during this early stage of the PALAR process, a problem identification process was followed to help the teachers come to a collaborative understanding of the possible contextual psychosocial challenges experienced by learners. Activities were followed by regular verbal group reflection and written individual reflections, as time allowed.

The relationship building exercises aimed to encourage trust among the participants (Zuber-Skerritt & Teare, 2013), develop understanding of each other's life circumstances, and also to acknowledge the participants' life experiences (Chilisa, 2005; Wilson et al., 2007) to thereby encourage the use of participants' existing local knowledge (Chilisa, 2005; Fasokun et al., 2005) and wisdom. The exercises allowed the project participants to realise their common problems (Zuber-Skerritt, 2012) and shared desire to support their learners. The shared goal was aimed at helping to shape their identity as a collective as they collaboratively identified the psychosocial challenges experienced by their learners.

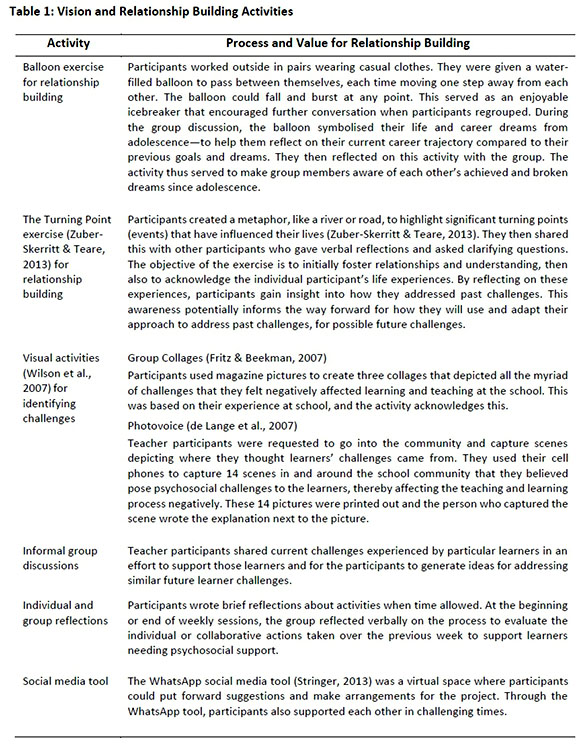

Data generation consisted of the video-recorded informal group discussions and reflections on the various exercises, as well as visual data (de Lange, Mitchell, & Stuart, 2007; Wilson et al., 2007) as a stimulus to promote active participation and to acknowledge their existing knowledge of the context (Kearney et al., 2013). Participants took photos within the community to highlight contextual psychosocial challenges (Wilson et al., 2007). For the photovoice narrative, they each wrote explanations next to the photographs related to the psychosocial theme, thus allowing the individual teacher participants to visually and then verbally express their understanding of contextual challenges (de Lange et al., 2007). WhatsApp messages as a tool of communication among participants were included as data (Stringer, 2013). The participants also created collages of the contextual challenges using magazine pictures to triangulate the photovoice artefacts. Data were analysed thematically (Merriam, 2009) together with the participants (Mertens, 2010), which encouraged them to re-search the challenges for further analysis (Minkler, 2005) and action. Throughout the initial process, the participants collaborated to reach consensus on the psychosocial challenges faced by learners in their school community. Table 1 below, summarises data generation for the first cycle of the PALAR process and consists of activities for vision and relationship building.

The use of various data sources ensured crystallisation (Mertens, 2010) of verbal and visual data, thus allowing the data to be understood from different vantage points in order to substantiate research findings. This PALAR project was conducted within the community in accordance with the stringent ethical requirements of the Research Ethics Committee of the North West University, who approved the research project. The facilitator's adherence to the Health Professions Council of South Africa's ethical code as a registered educational psychologist also ensured ethical practice in the interest of participant wellness (Myers & Sweeney, 2008).

Findings and Discussion

Themes based on the data analysis will be explored, with a focus on the participating teachers' own experience of the PALAR process for understanding the psychosocial challenges facing learners at their school. The verbatim quotations that support the discussion are given in text, under the relevant theme. Participants are labelled from A to J to ensure anonymity. Spelling and grammar in the quotations appear as in the original data.

Theme 1: Relationship building activities helped teachers to become aware of their own support needs.

The first stage of the PALAR cycle, particularly relationship building (see Zuber-Skerritt & Teare, 2013, Table 1), encouraged participants to critically reflect on their personal needs as related to professional practice and competence when supporting learners:

Those activities have helped me a lot because some of the things that I did not know about myself I now know them and I need to know more about them, especially the balloon exercise . . . that my dream, I don't know should I say does it [dream] look far or near . . . but I have realised something about my actual dream. (Participant H)

The process also served a positive therapeutic function in which the teacher participants coached one another on how to deal with personal challenges, an important prerequisite for being able to help others:

The project in general is very good. You remember last time I told you I am reaching this burn out. . . . It [the process] helped me not to give up. So I think this is a very good programme . . . it has done a difference because you know you remember last time a very big group started but this time the group shrinked to be small, so we know each other better now. (Participant E)

The relationship building activity encouraged teacher participants to discuss their personal experiences, which they had previously not shared easily with colleagues. The smaller group had created a space to get to know and support one another and to remind one another of the capacity each one has for making a difference by being part of a process to actively address the identified challenges. The painful lessons from their own life narratives motivated them to want to take action to support learners with similar life challenges, thereby applying the concept of transformative learning (Mezirow, 1991), where personal life experiences are reflected on to benefit others in the community.

Theme 2: Empathy, personal reflection, and character building were encouraged within the collaborative and reflective research space.

During the relationship building sessions, individual participants shared their personal triumphs, challenges, hurtful experiences, and family problems in a safe environment, often with cathartic results that promoted empathy and mutual trust. Participant C empathised with Participant B after he spoke about the death of his wife and child: "I never knew that Participant B had also been through these same painful experiences as me."

In professional spaces, coworkers tend to be inhibited to share personal issues, but the reflective action research space encouraged coparticipants to see each other differently, to shift perspectives and become respectful of each other as they better understood the challenges their colleagues experienced: "You know it is very powerful . . . it shows we cannot begin to judge each other . . . to me it is a motivation" (Participant A).

While facilitative communication (Stringer, 2013) prompted supportive responses to each other's personal narratives and promoted the project goals, the critical reflections at times created discomfort when participants realised the need to be open to new approaches because this challenged them personally and professionally:

I think we can help each other . . . In the past I thought you can't go to ask anybody . . . because they don't care . . . now I know especially with a boy I can go to Participant B or E. (Participant F)

These are the things we need to face, but try to push them away. Fatlhogang [name of the group] was here for us so we can accept that it is really sort of a problem solver for me to work In a proper way In the school. But It's like I am In denial, I am afraid of that things of saying: "What if Fatlhogang is going to see the faults in me" and I know that there are some other things that I didn't do it right. I have got that fear as a teacher.... That is how I experience it because most of the things that you did [PALAR activities] they do boil back to me as the teacher, even when I want to put the blame on kids, when I want to put the blame on parents, but at the end of the day, my role as teacher, I didn't do it." (Participant D)

However, this discomfort is a necessary part of personal growth (Zuber-Skerritt, 2012) and is enhanced through critical reflection in a safe space. The participants reflected on their personal experience to gain a deeper understanding of themselves and then integrated their new awareness into their current professional practice (Zuber-Skerritt, 2011) when responding to their learners' contextual challenges:

You know going out, taking those pictures really touches me a lot and it really makes me to want to go on helping. . . . That is why I wanted to engage more so that I maybe can get healed. . . . Since we have started this . . . everything that we have done especially on the learners' side, I link that with my growing up. And that is again that what makes me to work harder. Work harder at this Fatlhogang so that I can maybe aid or help learners to go through smoothly . . . like my father used to beat my mum, yes. And when we talk to those learners I sometimes hear [learners say] . . . "my dad was beating my mum and" and that is exactly what happened to me. (Participant K)

Theme 3: A sense of group identity to promote personal and collective agency emerged.

The participants brainstormed and democratically decided on the name Fatlhogang for their group, which means "to be enlightened" in Setswana (indigenous South African language). One of their goals was to create awareness among learners that they can overcome challenges with the correct support. The logo they designed (see Figure 2) shows people holding hands, symbolising working together, with orange and blue symbolising light and hope respectively, and with "Light at the end of the tunnel" as their motto.

Participants reflected verbally and in writing on how the process created a keener sense of their professional practice and purpose, to the extent that Participant H reflected that she would still participate in Fatlhogang even after her retirement the following year: "This process has reminded me where I came from . . . how far I have come . . . it makes me realise that there is still such a lot to do for the institution [school] even after I retire."

Participant C reported how he takes the process beyond the school and this allowed him to give support to his siblings:

I even told my mum about this programme... what I am doing [for] other kids. . . because I cannot see myself achieving it with others and without starting with them [at home] . . . I just wanted to ask my mum about our family name because it is important to know . . . you need to know [your identity] otherwise it brings up this resentment.

He had gained deeper awareness of his potential for helping through reflectively integrating his new knowledge and existing personal knowledge to benefit his learners and family. This suggests that, through the collaborative process for identifying psychosocial challenges at school, the participants started to realise their potential agency:

We are working well as group members and I do believe if we really can hold each other's hands we can be able to make many people to work with us, especially by that one where we were taking photos and identifying the types of places whereby our learners are living and how we can improve those places. (Participant H)

The awareness of their potential to collaboratively address the identified challenges is one of the transformative aims of a PALAR process (Zuber-Skerritt, 2012; Zuber-Skerritt & Teare, 2013).

T-shirts with the Fatlhogang logo were printed for each member at their request, which promoted group identity and seemed to create a sense of confidence among the participants, because it was at this point that they decided to invite other stakeholders on board. Fatlhogang teachers gave collaborative feedback about the research process to the entire staff. The feedback from other teaching and administrative staff indicated support for the process thus far. It was clear the research participants had started to take ownership of the process

At a memorial service for a 13-year-old learner who had passed away from HIV-related cancer, Participant L invited the parents, learners, and members of the public to approach Fatlhogang with any school-related problems they might be experiencing. Fatlhogang members invited parents and learner representatives serving on the school governing body to a meeting to create awareness among these stakeholders about the learners' psychosocial challenges and invite them to collaborate to begin to address them. This is evidence of the emergence of transformative learning (Zuber-Skerritt & Teare, 2013) toward collaborative action in comparison to previous ad hoc responses to challenges. Parents at this meeting requested a team building day for staff and parent representatives to get to know each other better. Fatlhogang members also started to generate data at school related to the number of learners living with extended family members or without any adult supervision, as the start of a project for providing support to such learners. During the final meeting of this first cycle of the PALAR process, the participants indicated their intention to take this process to surrounding schools after evaluation of the second cycle and to then expand on the Fatlhogang project so that interested teachers at other schools may be encouraged to use a similar PALAR process to identify and address contextual psychosocial challenges. Their long-term goal is to set up structures and a database that will guide teachers to follow this same process for identifying and addressing contextual psychosocial challenges.

Theme 4: The use of communication technology promoted collaborative action to support each other and learners.

During this cycle, participants respectfully motivated each other to achieve their personal and professional goals as equals, helping to minimise power relations within the group and promote collaborative action. One challenge with this process was that the group found it difficult to make decisions unless all participants were present. The WhatsApp social media tool fortunately became a space through which participants could put forward suggestions freely without face-to-face tensions. This encouraged symmetrical communication and group synergy (Myers & Sweeney, 2008). Through the WhatsApp tool, participants also supported each other in challenging times of illness, bereavement, and daily life challenges of their own or learners and thus promote wellness. The challenge with using WhatsApp was that not all participants possessed the relevant technological devices to participate equally, and at times were unaware of developments until they actually met another participant. The following are excerpts from Whatsapp messages sent by teacher participants to one another:

Hi to all, can we all pls pray for. . . [learner who had terminal cancer], he so much wish to come to school n his condition prevents him to. (Participant E)

On behalf of Fatlhogang crew . . . be blessed and get well soon . . . take a break and relax, remember you only have 1 life to live. (Participant L)

Leave your worries, stress, anger or any illness and start a new life. You r God's property. (Participant H)

The following message was sent on WhatsApp when a fellow teacher passed on after a severe diabetes episode during the second term school holiday: "Today let your actions speak louder than your words.

Give encouragement to the teachers, principal and administrators as a new school term begins" (Participant L).

They also used the WhatsApp tool to communicate around action for the way forward. The following words of Participant B suggest that sessions became personally meaningful, supportive, and motivating with regard to action in supporting learners: "I didn't feel like coming [to school] today but when I think of this session I just sprang out of bed . . . it's better to work as a team compared to previously when each helping [learners] individually."

Theme 5: Following a systematic process made challenges appear more manageable.

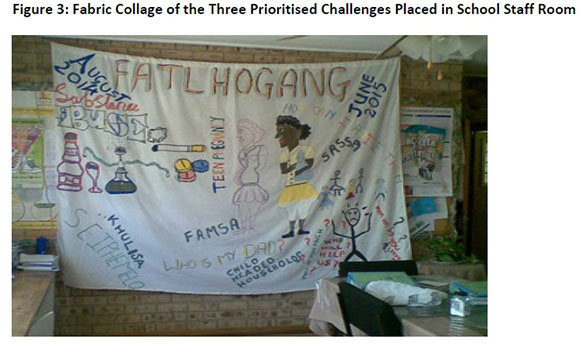

The participants initially identified 28 psychosocial challenges affecting learners, which was overwhelming. The facilitator suggested the nominal group technique (Dick, 1991; Zuber-Skerritt & Teare, 2013) whereby the participants could prioritise the most urgent challenges to address. The nominal group technique (NGT) is a process where individual participants give numerical value to issues in order of significance to the individual. Scores are then tabulated to identify the issues with the highest scoring for the group. The three prioritised challenges as mentioned below were represented visually on a 3 m x 2 m fabric (Figure 3):

• Learners are carrying adult responsibilities due to parents being unavailable

• Substance abuse

• Teenage pregnancy

The teacher participants decided to begin with finding ways to support learners who experience the three prioritised challenges through referral networks and by creating awareness among the learners at school level. They decided to reflect at monthly meetings on the progress for addressing the three issues over a period of 10 months. The fabric collage in Figure 3 created awareness of the PALAR process among other teachers, learners, and parents at the school. The collage was hung in the staffroom to encourage dialogue among staff. It was also exhibited with explanations to learners at assembly and to parents at a parents' meeting. Participants perceived the three psychosocial challenges as interrelated, particularly when children are vulnerable in the absence of parental care.

Current research also suggests that these three psychosocial challenges are interrelated within the socioeconomic reality of under-resourced communities in South Africa, negatively affecting personal and community wellness (Donald et al., 2010; Ward et al., 2014). HIV-related illness and death of parents are realities associated with the phenomenon of child-headed households in South Africa (Pillay, 2012) where older children are expected to perform caregiving responsibilities for siblings (Sloth-Nielsen, 2004) and sometimes also for ailing parents. The migrant labour system in South Africa (Hall & Wright, 2010), as a legacy of colonialism and apartheid (Bennett, Hosegood, Newell & McGrath, 2015; Lu & Treiman, 2006), currently also contributes to children carrying adult responsibilities. These two factors have also disrupted family structures (Hall & Wright, 2010; Lu & Treiman, 2006). The absent father phenomenon is a reality in South Africa (Makusha & Richter, 2014), resulting in increased responsibility on single mother figures who are often overburdened and unable to parent successfully (Makusha & Richter, 2014). These realities are directly related to the fact that almost 1% of the population of about 50 million South Africans live in child-headed households (Meintjes, Hall, Marera, & Boulle, 2009), where the older children at times must prioritise menial labour over school attendance to support the family financially. Those who remain at school may perform poorly due to their increased family responsibilities (Ibebuike, van Belkum, & Maja, 2014). The strain of being responsible for younger siblings may cause anxiety, resulting in poor concentration in class and poor attention to homework, resulting in poor academic performance (Tsegaye, 2008). In an attempt to cope financially, some girls in these contexts turn to men who will provide financial assistance for temporary periods, but then add to their problems through unwanted pregnancies (Miller et al., 2014; Theron, 2009) or HIV infection. Transactional sex (Potgieter, Strebel, Shefer, & Wagner, 2012) in these contexts is at times a conscious choice by some girls to generate an income (Ibebuike et al., 2014). Teenage pregnancy may also be fuelled by boredom (Miller et al., 2014), alcohol, and other substance use (Davis & Steslow, 2014; Tlale & Dreyer, 2013) in under-resourced communities where few other leisure options exist. This reality places these adolescents at greater risk for HIV infection in a population where the estimated HIV prevalence among antenatal clinic attendees in 2010 was already 14% for girls aged 15-19 years in South Africa (Blignaut, Vergnani, & Jacobs, 2014) and is steadily rising in periurban contexts. Social research indicates that children who are in a healthy relationship with their parents are more likely to make safer life choices (Brown, Gourdine, Waites, & Owens, 2013). The absence of parents in the context of child-headed families and the migrant labour system therefore paints a worrying picture, adding to the typical challenges of parenting in the 21st century (Zuber Skerritt & Teare, 2013)

The research speaks directly to the 28 wellness challenges as identified during the PALAR process. The NGT allowed the participants to identify a starting point for addressing the myriad of challenges, which previously had appeared overwhelming and which impact negatively on the wellness of teachers and learners (Myers & Sweeney, 2008). The dynamics linking the many challenges also highlights the link between wellness and social justice, where the poverty-related challenges cannot be divorced from the wellness of the community at large (Prilleltensky, 2013). The participants collaboratively categorised the remaining 25 challenges into the following categories for addressing in future as part of the ongoing PALAR process: (1) Negative modern and traditional cultural influences, (2) Poor home environment, (3) Socioeconomic challenges and (4) School environment.

Theme 6: Participants encountered challenges impacting on the potential success of PALAR process.

The challenges experienced by the teacher participants during Cycle 1 of the PALAR process had a direct bearing on achieving the aims and timeframes as decided on by the teacher participants during their vision building activity for the project. The challenge of time as related to their various life roles was repeatedly mentioned by participants. They felt motivated to take action, but felt they could accomplish more if more time was available "because we only meet once a week and sometimes others have commitments . . . I think that if maybe we had more time there could have been more that could have been done (Participant E)."

There were times when those in attendance became frustrated by the lack of progress because of the absenteeism of others. They questioned the commitment of participants. The facilitator contained the situation and encouraged teacher participants to reflect on the contextual challenges in their community and the influence on participating teachers. Fortunately, the group cohesion and commitment encouraged participants to be patient with each other. For the facilitator, the biggest challenge was also to be reflexive and accommodating of the commitments of participants to their other life roles when, often, sessions were cancelled at the last minute for school-related activities or because participants had to attend to learners or family responsibility. This reality was demotivating to the facilitator at times because progress was slow. There were, however, also "momentum waves" where teacher participants were proactive and achieved project goals in short spaces of time. This is a reality of the context in which this PALAR process was unfolding.

The findings from the analysis of the first cycle of the PALAR process suggest that the participating teachers understand each other much better after the relationship building process. This set the tone for collaborative interaction (Zuber-Skerritt, 2012; Zuber-Skerritt & Teare, 2013) where they could draw on personal experience (Chilisa, 2005) to enhance their existing knowledge and skills (Zuber-Skerritt & Teare, 2013). The participants developed a deep sense of professional, personal, and group identity that encouraged them to engage collectively and reflexively with each other and later, with other stakeholders, to explore ways to support learners coming from challenging psychosocial contexts to improve wellness within the school community.

The initial focus on relationship building allowed for the creation of a democratic and humanising space. Within this supportive environment, the Fatlhogang members reflected on the issues they face personally and then professionally and how these impact on wellbeing. The reflections promoted transformation and character building of the participants (Chilisa, 2005), and the resultant learning potentially contributed to theory and practice (Zuber-Skerritt, 2011). This process encouraged a critical attitude and promoted creative discussions and collaborative interactions (Stringer, 2013) to address real-life problems (Zuber-Skerritt & Teare, 2013) with all stakeholders in comparison with previous individual and ad hoc reactions to challenges the participants experienced at work and personally.

Interactions during the process encouraged empathy and ownership of the larger action research project, with teacher agency (Mertens, 2010; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003) gaining momentum as they collectively identified and categorised the psychosocial challenges faced by their learners. They started to recognise their personal and collective agency, which may not have been apparent to them before they started the PALAR process because they were previously overwhelmed by the contextual challenges. During this first cycle of the iterative PALAR process, participants successfully created a collaborative understanding of their concerns and negotiated a working relationship where, even when individual attendance was not possible, the participant still remained part of the process. Participants invested personally in the process and came to understand one another well enough to take collective ownership. Through interacting as collaborative coresearchers, they exercised their personal and collective agency for addressing the challenges they identified as affecting learners at their school.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the interactions and reflections of participants during this first cycle of the PALAR process indicate that these participants have benefitted personally and professionally through the process of repeated action, observation, and reflection within a trusting environment. While contributing to theory on how a PALAR process can support teachers to support learners, the process also improved participants' professional capacity for reflective transformation through democratic partnerships. The iterative trial-and-error approach of PALAR appears messy, but the strength lies in that it allows community participants to contribute to the process at any point. Even though time and effective communication posed significant challenges, the outcomes suggest that the PALAR approach is an option for teachers to initiate sustainable action to support learners with psychosocial challenges. The process was facilitated by the use of visual research methods that provided an avenue for teacher participants to voice their concerns and to reach a collaborated understanding of learner challenges in a non threatening process. The challenges of time, communication, and commitment to other life roles are realities of a community-based project, but through reflecting collaboratively, solutions can be generated. The emphasis for future PALAR projects should be on the time required for relationship building at the beginning. The strong bonds formed during relationship building become a resource for the participants during challenging times and encourage sustainability for the cycles that follow. The PALAR process for teachers in South Africa is a novel way of improving their practice and praxis in challenging contexts. Reporting on this PALAR project that helped the participating teachers identify and address psychosocial challenges faced by learners, adds to existing literature in the area of teacher support, and encourages teacher agency for collaboratively addressing challenges in their particular context.

While this research is based on improving wellness at one particular South African school, findings may encourage other teachers to adopt a PALAR process to understand and address contextual challenges affecting learner and teacher wellness in their respective school communities. The findings clearly suggest that by implementing a PALAR process, teachers can collaboratively address contextual wellness issues of school children that have a direct impact on learning and teaching.

Acknowledgements

We hereby acknowledge the teachers who initiated and participated in the project to identify and begin to address psychosocial challenges that negatively impact on teacher and learner wellness in their school community, for both their personal and professional contribution to the first cycle in this PALAR project.

A grant from the National Research Foundation (NRF) enabled the research reported on here. Any findings, opinions, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and therefore the NRF does not accept any liability thereto.

References

Bennett, R., Hosegood, V., Newell, M., & McGrath, N. (2015). Understanding family migration in rural South Africa: Exploring children's inclusion in the destination households of migrant parents. Population, Space and Place, 21(4), 310-321. [ Links ]

Blignaut, R. J., Vergnani, T., & Jacobs, J. J. (2014). Correlates of sexual activity versus non-activity of incoming first-year students at a South African university. African Journal of AIDS Research, 13(1), 81-91. [ Links ]

Brown, A. W., Gourdine, R. M., Waites, S., & Owens, A. P. (2013). Parenting in the twenty-first century: An introduction. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 23(2), 109-117. [ Links ]

Bruce, D. (2014). Control, discipline and punish? Addressing corruption in South Africa. SA Crime Quarterly, (48), 49-62. [ Links ]

Chilisa, B. (2005). Educational research within postcolonial Africa: A critique of HIV/AIDS research in Botswana. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 18(6), 659-684. [ Links ]

Davis, G. P., & Steslow, K. (2014). HIV medications as drugs of abuse. Current Addiction Reports, 1(3), 214-219. [ Links ]

De Lange, N., Mitchell, C., & Stuart, J. (2007). Putting people in the picture: Visual methodologies for social change. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense. [ Links ]

Dick, R. (1991). Helping groups to be effective: Skills, processes and concepts for group facilitation Chapel Hill, Australia: Interchange. [ Links ]

Donald, D., Lazarus, S., & Lolwana, P. (2010). Educational psychology in social context: Ecosystemic applications in southern Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford. [ Links ]

Fasokun, T. O., Katahoire, A., & Oduaran, A. B. (2005). The psychology of adult learning in Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: UNESCO & Pearson. [ Links ]

Freire, P. (2005). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). New York, USA: Continuum. (Original work published 1970) [ Links ]

Fritz, E., & Beekman, L. (2007). Engaging clients actively in telling stories and actualizing dreams. In K. Maree, (Ed.), Shaping the story (pp.163-175). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Hall, K., & Wright, G. (2010). A profile of children living in South Africa in 2008. Journal for Studies in Economics and Econometrics, 34(3), 45-69. [ Links ]

Herr, K., & Anderson, G. L. (Eds.). (2005). The action research dissertation: A guide for students and faculty. Thousand Oaks, USA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Hoadley, U. (2007). Boundaries of care: The role of the school in supporting vulnerable children in the context of HIV and AIDS. African Journal of AIDS Research, 6(3), 251-259. [ Links ]

Ibebuike, J. E., van Belkum, C., & Maja, T. M. (2014). An empowerment programme to support children in child-headed households in resource-poor communities in Soshanguve, South Africa: Phase 2 of an intervention study. BMC Infectious Diseases, 14(3), 29. [ Links ]

Joubert, I., Ebersöhn, L., Ferreira, R., Du Plessis, L., & Moen, M. (2014). Establishing a reading culture in a rural secondary school: A literacy intervention with teachers. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 49(4), 399-412. [ Links ]

Kearney, J., Wood, L., & Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2013). Community-university partnerships: Using participatory action learning and action research (PALAR). Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, 6(1), 113-30. [ Links ]

Kearney, J., & Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2012). From learning organization to learning community: Sustainability through lifelong learning. The Learning Organization, 19(5), 400-413. [ Links ]

Khanare, F. (2012). Schoolchildren affected by HIV in rural South Africa: Schools as environments that enable or limit coping. African Journal of AIDS Research, 11(3), 251-259. [ Links ]

Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Engelwood Cliffs, USA: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Lu, Y., & Treiman, D. J. (2006, July). The effect of labor migration and remittances on children's education among blacks in South Africa. Paper presented at World Congress of Sociology Durban, South Africa.

Makusha, T., & Richter, L. (2014). The role of black fathers in the lives of children in South Africa. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(6), 982-992. [ Links ]

Malindi, M. J., & Machenjedze, N. (2012). The role of school engagement in strengthening resilience among male street children. South African Journal of Psychology, 42(1), 71-81. [ Links ]

Mampane, R., & Bouwer, C. (2006). Identifying resilient and non-resilient middle-adolescents in a formerly black-only urban school. South African Journal of Education, 26(3), 443-456. [ Links ]

Mampane, R., Ebersöhn, L., Cherrington, A., & Moen, M. (2014). Adolescents' views on the power of violence in a rural school in South Africa. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 49(6), 733-745. [ Links ]

Masitsa, M. (2011). Exploring safety in township secondary schools in the Free State province. South African Journal of Education, 31(2), 163-174. [ Links ]

McKnight, J., & Kretzmann, J. (1993). Building communities from the inside out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a community's assets. Chicago, USA: ACTA. [ Links ]

Meintjes, H., Hall, K., Marera, D., & Boulle, A. (2009). Child-headed households in South Africa: A statistical brief. Cape Town, South Africa: The Children's Institute. [ Links ]

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (Revised and expanded from Qualitative research and case study applications in education). San Francisco, USA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Mertens, D. M. (2010). Research and evaluation in education and psychology: Integrating diversity with quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, USA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Fransico, USA: Jossey Bass. [ Links ]

Miller, J. A., Caldwell, L. L., Weybright, E. H., Smith, E. A., Vergnani, T., & Wegner, L. (2014). Was Bob Seger right? Relation between boredom in leisure and (risky) sex. Leisure Sciences, 36(1), 52-67. [ Links ]

Minkler, M. (2005). Community-based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Urban Health, 82(2), ii3-ii12. [ Links ]

Minkler, M., & Wallerstein, N. (2003). Introduction to community based participatory research. In M. Minkler & N. Wallerstein (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health (pp. 3-26). San Francisco, USA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Mncube, V. (2009). The perceptions of parents of their role in the democratic governance of schools in South Africa: Are they on board? South African Journal of Education, 29(1), 83-103. [ Links ]

Modisaotsile, B. M. (2012). The failing standard of basic education in South Africa. Africa Institute of South Africa, Policy Brief 72, (1-7). [ Links ]

Motshekga, A. (2010, February). Enhancing the Culture of learning and teaching in our schools for better education outcomes. Address by the Minister of Basic Education, Mrs Angie Motshekga, MP, to The National Council of Provinces on the occassion of the debate on the President's State of the Nation Address. Retrieved from http://www.gov.za/address-minister-basic-education-mrs-angie-motshekga-mp-national-council-provinces-occasion-debate

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2008). Wellness counseling: The evidence base for practice. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(4), 482-493. [ Links ]

Pillay, J. (2012). Experiences of learners from child-headed households in a vulnerable school that makes a difference: Lessons for school psychologists. School Psychology International, 33(1), 3-21. [ Links ]

Potgieter, C., Strebel, A., Shefer, T., & Wagner, C. (2012). Taxi 'sugar daddies' and taxi queens: Male taxi driver attitudes regarding transactional relationships in the Western Cape, South Africa. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 9(4), 192-199. [ Links ]

Prilleltensky, I. (2013). Wellness without fairness: The missing link in psychology. South African Journal of Psychology, 43(2), 147-155. [ Links ]

Sloth-Nielsen, J. (2004). Realising the rights of children growing up in child-headed households. Cape Town, South Africa: University of the Western Cape, Community Law Centre. [ Links ]

Spaull, N. (2013). Poverty & privilege: Primary school inequality in South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 33(5), 436-447. [ Links ]

Stringer, E. T. (2013). Action research (3rd ed.). California, USA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Teare, R. (2013) Building a case for evidence-based learning. In Zuber-Skerrit, O. & Teare, R. (Eds.), Lifelong action learning for community development: Learning and development for a better world (pp. 67-98). Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense. [ Links ]

Theron, L. (2009). The support needs of South African educators affected by HIV and AIDS. African Journal of AIDS Research, 8(2), 231-242. [ Links ]

Tlale, L. D., & Dreyer, S. E. (2013). Contextual influences of substance abuse problems among school children. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(13), 361-366. [ Links ]

Tsegaye, S. (2008). HIV/AIDS orphans and child-headed households in sub-Saharan Africa. Johannesburg, South Africa: African Child Policy Reform. [ Links ]

Ward, C., Mikton, C., Cluver, L., Cooper, P., Gardner, F., & Hutchings, J. (2014). Parenting for lifelong health: From South Africa to other low-and middle-income countries. Early Child Matters, 122, 4953. [ Links ]

Wilson, N., Dasho, S., Martin, A. C., Wallerstein, N., Wang, C. C., & Minkler, M. (2007). Engaging young adolescents in social action through photovoice the youth empowerment strategies (YES!) project. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 27(2), 241-261. [ Links ]

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2011). Action leadership: Towards a participatory paradigm. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. [ Links ]

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2012). Action research for sustainable development in a turbulent world. Bingley, UK: Emerald. [ Links ]

Zuber-Skerritt, O., & Perry, C. (2002). Action research within organisations and university thesis writing. The Learning Organization, 9(4), 171-179. [ Links ]

Zuber-Skerritt, O., & Teare, R. (2013). Lifelong action learning for community development: Learning and development for a better world. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense. [ Links ]