Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Literator (Potchefstroom. Online)

On-line version ISSN 2219-8237

Print version ISSN 0258-2279

Literator vol.43 n.1 Mafikeng 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/lit.v43i1.1819

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Exploring multilingualism at the national department levels in South Africa post the Use of Official Languages Act of 2012

Abel L. Mohlahlo; Thabo Ditsele

Department of Applied Languages, Faculty of Humanities, Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The main objective of this article is to explore how multilingualism (i.e. the use of three or more languages) is practised at the level of national departments in South Africa since the passing of new language legislation called the Use of Official Languages Act (No. 12 of 2012). In support of this main objective, the article seeks to establish the attitudes held towards languages and official multilingualism (i.e. multilingualism which is recognised by government) by national departments' employees responsible for matters related to language and communication. It also seeks to establish the perception of the general public on how public servants treat language when communicating with them. Data were gathered through document analyses, survey questionnaires (completed by employees at two national departments), and face-to-face interviews (with members of the public). Participants (i.e. national departments' employees and members of the public) held positive attitudes towards official multilingualism by supporting the development and use of all 11 official languages, particularly the historically marginalised Black South African languages (BSALs). Also, as far as these two national departments are concerned, the Use of Official Languages Act (No. 12 of 2012) was yet to be fully implemented as per its objects set out in its Preamble, as the language policies developed by these national departments were yet to be implemented.

Keywords: multilingualism; language policy and planning; language attitudes; national departments; South Africa.

Background

Before Act 200 of 1993 (known as the Interim Constitution of South Africa) was passed, Afrikaans and English were the only official languages in South Africa. This Act changed this scenario by giving official status to the following nine Black South African languages or BSALs (in alphabetical order): isiNdebele, isiXhosa, isiZulu, Sesotho sa Leboa, Sesotho, Setswana, siSwati, Tshivenda and Xitsonga. Act 200 of 1993 was replaced by Act 108 of 1996 (the current Constitution of the Republic of South Africa [Republic of South Africa 1996]), and the official status of 11 languages was retained. As Rakgogo and Van Huyssteen (2018:79-80) noted, the only change between the two constitutions was that Sesotho sa Leboa was referred to as Sepedi in the latter Act.

Mutasa (2003:290) observed that although BSALs have a place in the new South Africa as official languages, their home language (HL) speakers have a high regard for English. He further indicated that many HL speakers still believe that only English can effectively serve as an official or national language. Mutasa (1999:86) demonstrated that most linguistic communication in domains of national significance remains in English, and to a lesser extent, Afrikaans. Such communication patterns have created an impression that to be part of the national economy, one needs to have communication skills in these two languages, and not in the nine BSALs.

Section 6 of the Constitution of South Africa (1996) recognises that the nine BSALs are not as developed as Afrikaans and English, therefore they need to be institutionally supported. One measure to institutionally support them was the passing of Act 12 of 2012 (the Use of Official Languages Act), whose Preamble states that the State should take practical and positive measures to elevate the status and advance the use of these nine BSALs. In taking these measures, the Act tables these four objects:

1. To regulate and monitor the use of official languages for government purposes by national government.

2. To promote parity of esteem and equitable treatment of official languages of the Republic.

3. To facilitate equitable access to services and information of national government.

4. To promote good language management by national government for efficient public service administration and to meet the needs of the public.

Section 3(1) of this Act states that it only applies to national departments, national public entities and national public enterprises. In other words, it does not apply to provincial departments and municipalities.

Objective of the article

The main objective of this article is to explore how multilingualism is practised (if any) at national departments in South Africa since the passing of new language legislation called the Use of Official Languages Act. To support this main objective, the article seeks to establish the attitudes held towards language and official multilingualism by national departments' employees responsible for matters related to language and communication. It also seeks to establish the general public's perceptions on how public servants treat language when communicating with them. As such, the article poses the following research questions:

1. What attitudes are held by employees at national departments towards official multilingualism, which is promoted by the Use of Official Languages Act?

2. How do members of the public view the promotion of multilingualism from their interactions with government employees?

Conceptual background

Multilingualism in South Africa

As mentioned in the 'Background' section, through the Interim Constitution of South Africa passed in 1993, South Africa increased the number of official languages from 2 to 11, and this was endorsed in the current Constitution of South Africa, which was passed in 1996. Heine (1992:25) observed that many African countries adopted an exoglossic approach in dealing with the language question - they declared language, which originated in Europe as their sole official language. South Africa went against this tradition by adopting an endoglossic approach, one in which language with no official status (viz. the nine BSALs) was given official status alongside West Germanic languages (viz. Afrikaans and English).

The debate in South Africa is whether this multilingual approach was successfully implemented.

Heine (1992:24) cautioned against endoglossic nations that create an impression that they are multilingual when they are no different from exoglossic nations because they have not invested enough in promoting languages which were recently accorded official status. Scholars such as Alexander (2004), De Klerk and Gough (2002) and Mutasa (1999) argued that in South Africa, English still remains the language of power and prestige, and that this is evident in classrooms where teaching and learning occur almost exclusively in English. Also, English is largely used in all other domains of significant communication, whilst Afrikaans is used to a lesser extent. Looking at these submissions, the argument made is that official multilingualism is yet to be implemented in South Africa, and as things stand, the country remains an in-active endoglossic nation.

Perhaps, one of the reasons behind the failure in the implementation or delay thereof might be a lack of political will. Du Plessis (2000:104) submitted that the 11-language policy does not reflect the African National Congress's (i.e. a political party which has been in government since 1994) position which was advocating for an English-only agenda in the language debate at the Convention for Democratic South Africa (CODESA) negotiations. Had the Afrikaans negotiators not insisted on Afrikaans continuing to being one of the official languages in South Africa during negotiations to end the apartheid system during 1992-1993, the country could have adopted an exoglossic approach like many African countries.

Language attitudes

Before discussing language attitudes, it is necessary to define this term. Scholars concur that defining attitude is not a straightforward task, hence it has a fluid definition. Garrett, Coupland and Williams (2003) pointed out that even though attitude is one of the most distinctive and indispensable concepts in social psychology, defining it is not as straightforward. Garrett (2010) concurred with this and therefore submitted that 'definitions of the concept vary in their degree of elaboration'. Allport (1935:810), considered as a seminal author on attitudes, defined attitude as both a mental and neural state acquired through experience, informing how people respond towards certain objects, De Klerk and Bosch (1993:209) also supported this definition by Allport … Baker (1992:9), therefore, argued that attitude might be used to explain people's behaviour.

Whilst definitions of attitude vary, what is common amongst them is that attitudes are held towards or in relation to something or an object, people or any abstract phenomenon (e.g. capitalism, capital punishment, etc.). Eagly and Chaiken (1993:4) submitted that an evaluation is made with respect to an entity or thing. The said entity is known as an attitude object and one such object is language, hence the concept of language attitudes. However, language attitude is difficult to define, and Smit (1996:31) argued that this is because of the combination of concepts that are themselves multi-layered. Cooper and Fishman (1974:6) stated that it may be useful to define language attitude in terms of its referent, that referent being either a language or a feature of a language or language use.

Language planning and language policy

According to Eastman (1983:89), language planning refers to an activity of manipulating language in society, in an effort to achieve objectives set out by planning agencies, such as government officials, education sectors or language authorities. The process of language planning is rather complex and as such, Lo Bianco (ed. 2002:24) argued that it ought to be carried out by experts, such as government bureaucrats. There are different types of language planning and Kloss (1967:29) distinguished between two types: corpus planning, which is concerned with the internal structure of a language; and status planning, which refers to efforts undertaken to change the use and function of a language (or language variety) within societies.

Whether it is corpus or status planning, Alexander (2003:22) understood language planning as a discipline that seeks to find solutions to language-related problems. One of the ways through which such solutions to language problems could be pursued is through language policies. Simply put, a language policy refers to a document which explicitly outlines guidelines on what languages should be used within countries or institutions and how. Mann and Wong (1999:17) subsequently defined language policy as statements by government regarding the statuses and functions that selected languages have been assigned; Mutasa (2003:21) supported this definition by stating that it a decision by a country to allocate specified roles to a particular language or languages.

Policymakers and implementers need to fully understand the nature of language policies, and Noss (1971:25) presented three types, namely: (1) official language policy, which stipulates the languages which are to be used and how they should be used in government; (2) education language policy, which outlines languages that should be used as media of instruction (MOIs) in education and those that are to be used as subjects of study both in public and private schools and (3) general language policy, which outlines the languages which should be used in business, mass communication, and with foreign nationals.

Research approach

A mixed-methods approach was used to gather the data and that was informed by Creswell (2015) who suggested:

[A] core assumption of this approach is that when an investigator combines statistical trends (quantitative data) with stories and personal experiences (qualitative data), this collective strength provides a better understanding of the research problem than either forms of data alone. (p. 2)

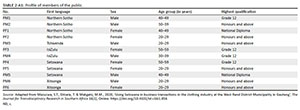

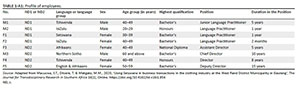

A questionnaire and interviews were used to gather the data. The questionnaire was used to gather quantitative data (i.e. a Likert-type scale comprising 12 belief statements related to language use) and qualitative data (i.e. five open-ended questions), and it was completed by employees (see Appendix Table 1 for their profiles) at two national departments (viz. ND1 and ND2). More qualitative data were gathered through face-to-face interviews with members of the public (see Appendix Table 2 for their profiles). Eight semi-structured questions were posed to the senior manager, and another eight semi-structured questions to members of the public.

Additional qualitative data were gathered through document analysis, that is, by reading the two national departments' language policies. Maree (ed. 2007:82) submitted that 'when you use documents as a data gathering technique, you will focus on all types of written communication that may shed light on the phenomenon that you are investigating'. Reading through the language policies (document analysis) was important because it helped the authors understand the national departments' responses to the implementation of the Use of Official Languages Act, as well as how their employees viewed official multilingualism because until this Act was passed, there were no specific legal requirements or obligations to practise multilingualism. Put differently, national departments exercised their discretion to support Section 6 of the Constitution of South Africa (1996) in recognising that the nine BSALs were not as developed as Afrikaans and English, thus they needed to be institutionally supported. The reading of the two national departments' language policies shaped the instruments used, that is, the belief statements in the Likert-type scale, as well as face-to-face interview questions.

Participants

The researchers intended to gather data from at least four national departments in Pretoria, and from between 24 and 32 employees (i.e. between six and eight per national department), they therefore targeted national departments with a mandate of providing a direct service to members of the public (e.g. health, social services, water, etc.) albeit through structures such as provincial departments. The researchers followed all the processes stipulated by the national departments they approached, including providing them with an ethical clearance letter. This proved to be a very challenging task on two fronts.

Firstly, senior managers at national departments were suspicious of the researchers' intentions as they suspected that the researchers intended to expose them for not being where the parliament expected them to be regarding the implementation of the Use of Official Language Act, thus refused to allow the researchers access to their employees, despite being assured that the researchers would use code names (e.g. ND1, ND2, ND3, etc.) to ensure that their identities were not disclosed.

Secondly, for the national departments that granted the researchers permission to access their employees, many potential participants (i.e. employees responsible for matters related to language and communication) who initially showed enthusiasm withdrew their participation as soon as they saw the questionnaire. They were assured that code names (e.g. M1 for first male participant, F4 for fourth female participant, etc.) were to be used to ensure that their identities were not exposed. However, they declined, and the common reason was that they feared victimisation, which could see them losing their jobs.

In the end, eight employees from two national departments agreed to complete the questionnaire. Purposeful sampling was thus used because the nature of this research was that national departments' employees were best placed to provide information needed to achieve its main objective, an approach supported by Struwig and Stead (2001:122).

Purposive random sampling was used to select participants drawn from members of the public. These participants were approached outside government facilities which serviced members of the public (e.g. health, social services, water, etc.). Palinkas et al. (2015:336) argued that purposeful random sampling increases the credibility of a researcher's findings. Approaching potential participants after they had interacted with officials was important because had they been approached before they received services that could have influenced them in how they interacted with officials and that would have contaminated the data.

The study was granted ethical clearance by the Faculty Committee for Research Ethics (Humanities), Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria with ethical clearance number FCRE/APL/STD/2017/19.

Findings

Data were analysed in this order. Firstly, document analysis (i.e. the correlation between language policies and observations), secondly, Likert-type scale (i.e. 12 belief statements) and thirdly, face-to-face interviews. To organise the analysis of data better or coherently, the following four themes were developed: (1) language development; (2) convenience of English; (3) language practice within government and (4) social cohesion.

Correlations between language policies and practice (qualitative data)

According to the language policy of the first national department (ND1), three languages (i.e. English and two BSALs) were selected as official languages, whilst the language policy of the second national department (ND2) stated that it had selected 11 official languages, that is, all official languages of South Africa.

The researchers observed that what was set out in both national departments' language policies did not translate into official multilingualism and that in practice, they adopted an English monolingual approach. For instance, their service charters on display to members of the public were written only in English. Their signages and notices were written only in English, and many forms (e.g. applications forms for employment, etc.) were written only in English. The researchers requested copies of the language policies in languages other than English, but were informed that these were not yet available.

As far as the researchers could ascertain, the two national departments conducted their business as if the Use of Official Languages Act did not exist, that is, official multilingualism as set out in the Act only existed in their language policies.

Likert-type scale (quantitative data)

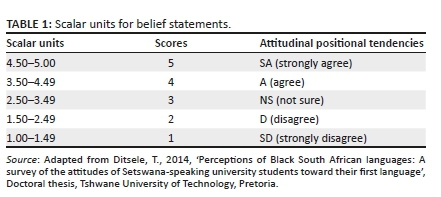

The following five levels were used to establish national departments employees' attitudes towards language and multilingualism: (1) strongly agree; (2) agree; (3) not sure; (4) disagree and (5) strongly disagree. Table 1 shows the scalar units, scores and attitudinal positional tendencies that were used to analyse the 12 belief statements.

Statistical means were used to determine participants' attitudinal positional tendencies. The small number of participants rendered any rigorous statistical analysis (e.g. the use of Statistical Package for the Social Sciences [SPSS] to determine statistical significance, etc.) impossible. Because of the weakness of a small number of participants, the researchers did not make any generalisations from what they established from the statistical means. Each of the 12 belief statements was classified under one of the four themes as follows:

1. Theme 1: Language development (Belief statements 1, 4 and 7).

2. Theme 2: Convenience of English (Belief statements 2, 6 and 10).

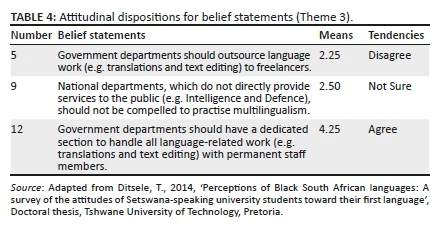

3. Theme 3: Interaction between government and the people (Belief statements 5, 9 and 12).

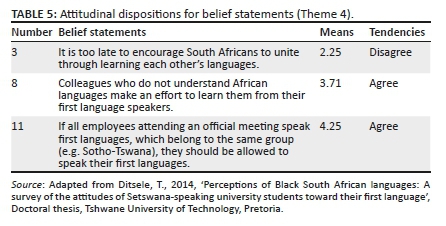

4. Theme 4: Social cohesion (Belief statements 3, 8 and 11).

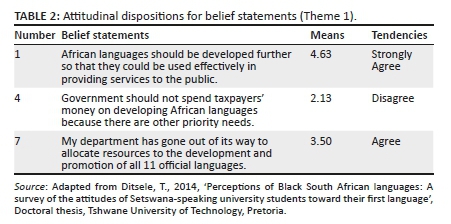

Theme 1: Language development

This theme explored the development of BSALs, referred to as African languages on the research instrument to avoid uncertainty amongst the participants. As shown in Table 2, participants strongly agreed that BSALs should be developed further so that they could be used effectively in delivering services to the public, and they agreed that government should invest money in developing BSALs.

The participants also believed that their national departments had invested resources in the development and promotion of all official languages. A key aspect of the three belief statements is that participants supported the development of language in general, and BSALs in particular.

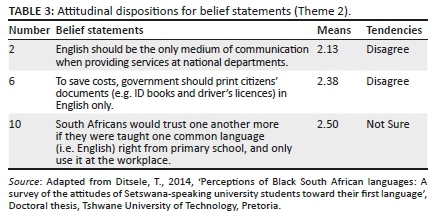

Theme 2: Convenience of English

In South Africa, English is the most used or preferred official language in formal settings (e.g. media, formal education, workplace interactions, etc.). This theme sought to establish whether participants were included towards English monolingualism (see Table 3).

They disagreed that English should be the only language used by national departments for the purposes of service delivery, and they also disagreed that documents provided to citizens should only be in English. They were not sure whether regulating that English be a common language taught to citizens and communicating exclusively in it at workplaces would improve the trust deficit amongst citizens. Taken together, participants did not support English monolingualism, and they seemed convinced that space should be created for the other official languages.

Theme 3: Interaction between government and the people

The Use of Official Language Act was necessitated by the fact that the use of language within government was not clear, and the fate of official multilingualism was left in the hands of individual national departments; in other words, official multilingualism was arbitrary. The emergent theme established what participants felt about language practice within government (see Table 4).

The participants supported the idea of keeping language work within government departments, and such work should be done by staff members employed on a permanent basis. However, they were uncertain about national departments which do not directly service members of the public being forced to conduct business in multiple languages. In summarising the three belief statements, participants were convinced that language work should be carried out within government and not outsourced.

Theme 4: Social cohesion

Before South Africa became a democracy in 1994, Afrikaans and English received institutional support from government. Such institutional support developed them into languages of social upward mobility and those who could not speak them as HLs were compelled to develop communication skills proficiency in these same languages. They were, and continue to be, default languages used in interactions between people of different races and ethnicities, particularly amongst white-collar employees. The purpose of this theme was to explore whether participants believed that language could be used for social cohesion (see Table 5).

The participants believed that it was not too late for South Africans to learn languages in which they were not proficient, and that those who lacked such skills in BSALs were making an effort to learn them. The current practice across boardrooms in South Africa is that meetings are conducted in English (in the main) and Afrikaans (to a lesser extent), and that minutes are recorded in English. Participants believed that social cohesion could be strengthened amongst those who communicate in languages which are mutually intelligible by allowing them to conduct business in such languages.

Face-to-face interviews (qualitative data)

Face-to-face interviews were held with 12 members of the public (see Appendix Table 2) and nine questions were put to them:

1. Theme 1: Language development (Questions 1 and 2).

2. Theme 2: Convenience of English (Question 3).

3. Theme 3: Interaction between government and the people (Questions 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9).

For these participants, the researchers wanted to understand their experiences whilst receiving service from government officials, that is, whether official multilingualism was practised. This explains why six out of nine questions addressed Theme 3, each one addressed Themes 1 and 2, and none addressed Theme 4. It is important to note that the researchers were interested more in the depth of participants' experiences, as opposed to how many agreed or disagreed with the question posed to them. As such, their numbers are reported on for the purposes of demonstrating how they felt about a specific language use aspect put to them. The interviews were conducted by one of the authors and in languages which participants were comfortable using.

Theme 1: Language development

Question 1: Is there a need for South Africa's 11 official languages to be equal in status?

All 12 participants said YES to the question. Three of them stated that there was a need for consistency between what was stipulated in the country's Constitution (1996) about equality and what was practised on the ground. They stated that government institutions needed to act in accordance with the Constitution (1996). PM4 stated:

'[C]onsistency is important because the Constitution of South Africa says that everybody is equal before the law and to achieve that, we should start by developing our languages so that they enjoy equal status.'

Five participants stated that government needed to be inclusive of all citizens, and that people who did not understand English, the dominant language should be accommodated by availing information in their HLs. One of them was PM2 who said:

'[E]nsuring that all official languages are equal ensures that they are maintained and kept alive.'

The remaining four participants submitted that language, identity and culture go together, therefore preserving all official languages meant preserving all citizens' identities and cultures. PM5 said:

'[L]anguage forms part of a people's identity, and in a country like South Africa where there is diversity in cultures and languages, people need to feel that they are as important as those who speak other languages.'

Question 2: Do you think using your HL for official government purposes would develop it?

Ten participants agreed that using their HLs for official government purposes would go a long way in ensuring that they are developed and remained relevant. One of them was PM2 who remarked:

'[I]f my HL can be used for government purposes like English and Afrikaans, it could develop and eventually be at the same level as these two languages.'

The other two participants said that they did not know how to answer the question.

Theme 2: Convenience of English

Question 3: English is widely used for official purposes in the country; do you think it should be made the only official language?

All 12 participants disagreed that English should be the only official language in the country. They suggested that BSALs should be developed to the level of English. PM2 stated:

'[M]aking English the only official language will further foster inequality in South Africa, and we cannot afford that.'

Theme 3: Interaction between government and the people

Question 4: Upon arriving at this government facility, are you presented with language options from which you get to choose the one you prefer to be assisted in?

Ten participants stated that they were not presented with language options from which they could choose the one they were comfortable being assisted in, and only two said that they were. PF5 added:

'[E]verything is in English, and sometimes explanations are done in the government official's preferred language, not mine.'

Question 5: Have you ever been serviced in your HL or any language of your choice at this government facility, for example, being spoken to or receiving correspondence in it?

Ten participants stated that they had been serviced in their HLs, whilst the other two had not. Those who had been serviced in their HLs stated that this was done only orally when government officials explained to them in languages other than English and Afrikaans. Documents they received were in English and Afrikaans and not in their HLs. PM2 had this to say:

'[O]fficial documents are written in English and Afrikaans, and others are written only in English. However, officials have on numerous occasions spoken to me in my HL.'

Question 6: Do you insist, or have you ever insisted on being given documents (e.g. driver's licence, ID book, etc.) written in your HL?

Seven participants said that they had never insisted on being serviced in their HLs, whilst five said that they had. PM2 is one of those who had insisted, and he said:

'[I] do not insist because most of these documents are already printed in English and Afrikaans, and that gives more advantage to speakers of these languages.'

Question 7: After insisting on being given documents (e.g. driver's licence, ID book, etc.) in your HL, did government officials deliver on your choice of language?

This question was put to five participants who, in Question 5, said that they insisted on being serviced in their HLs. All of them stated that even after insisting on being served with documents written in their HLs, they were served with documents written in English. PM5 responded as follows:

'[I] was told that documents were only printed in English.'

Question 8: How important do you think it is that official correspondence between the government and the public be availed in all official languages?

Eleven participants stated that it was very important that correspondence between government and the public be accessible in all official languages. One participant (i.e. PF1) said that it was not important to her because once explanations had been made in her HL, she did not mind when she was served with documents written in English. PF5 was one of those who supported documents being in all official languages, and he said:

'[I]t would be a challenge if, for example, medical records from a public hospital are written in English and the patient that they are addressed to has no understating of the content; not everyone understands English.'

Question 9: What do you think would motivate government officials and employees to start rendering service to the public in all official languages?

Two participants said that they did not know how to answer the question, whilst 10 made suggestions which belonged to two categories: (1) demanding official multilingualism, and (2) language awareness. With regard to the first category, PM2 remarked:

'[I]f we, as citizens, can start embracing our languages, insist on being serviced in them, then government officials will start rendering service to the public in all official languages.'

Looking at the second category, PF6 submitted:

'[I]f civil society raised awareness about the importance of embracing all official languages and the importance of using all of them equally, then government will service citizens using all of them.'

Discussion

Except for Theme 4 (social cohesion) where data analysed under this theme were gathered from employees of two national departments, data for the other three themes were gathered from the employees of these two national departments, and members of the public. That said, data from the two groups of participants are collated and discussed in this section.

Theme 1: Language development

Participants were of a view that BSALs should be developed to a level where they are at par with English and Afrikaans in terms of status and use. That way, they would be languages of prestige, upward social mobility, and it would be easy to use them for government purposes in the same way as English and Afrikaans.

Theme 2: Convenience of English

Participants did not support the idea of English being the only official language to the exclusion of Afrikaans and the nine BSALs. However, they acknowledged that it was convenient to use English for government purposes.

Theme 3: Interaction between government and the people

Participants acknowledged that currently, interaction between government (through its employees) and members of the public was skewed in favour of English and Afrikaans, and at the expense of BSALs. Members of the public were unambiguous about their support for official multilingualism, and employees at national departments were also unambiguous about their support for language work being kept within government as opposed to being outsourced.

Theme 4: Social cohesion

Employees at national departments agreed that social cohesion (and by extension, nation-building) could be fostered by South Africans through learning each other's HLs, particularly by HL speakers of the more dominant languages in formal settings (viz. English and Afrikaans) learning BSALs, which are not dominant in formal settings.

Conclusion

The main objective of this article is to explore how multilingualism is practised at national departments in South Africa since the passing of new language legislation called the Use of Official Languages Act (No. 12 of 2012), and to achieve that objective, two research questions were asked and are answered in this section.

With regard to the first research question, the researchers conclude that national departments' employees generally held positive attitudes towards official multilingualism because they supported the development and use of all 11 official languages, particularly the historically marginalised BSALs. These participants also rejected the idea of an English-only approach in government communication with South Africans, and they believed that language work (e.g. translations, text editing, etc.) should not be done by practitioners employed on a full-time basis by national departments.

Regarding the second research question, whilst members of the public pointed out that communication between them and employees at national departments was mainly in English and in Afrikaans to a lesser extent, they felt that practising official multilingualism would be inclusive of all citizens, particularly those with no communication skills in English and Afrikaans. The researchers thus conclude that these participants fully supported the promotion of official multilingualism in government communication with citizens.

Whilst the two national departments had taken steps to develop their language policies in accordance with the Use of Official Languages Act, their employees' responses and the authors' analysis of documents suggested that the two national departments were yet to translate their language policies into practice. As such, the researchers' major conclusion is that, as far as these two national departments are concerned, the Use of Official Languages Act was yet to be fully implemented as per its objects set out in its preamble, specifically object (b) which says: 'To promote parity of esteem and equitable treatment of official languages of the Republic' and object (c) which says: 'To facilitate equitable access to services and information of national government'.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our sincere appreciation to the 20 participants for their engagement in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

This article was written out of A.L.M's Master's research project under the supervision of T.D. A.L.M. drafted the article, whilst T.D. revised and finalised it.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Faculty Committee for Research Ethics (Humanities), Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria. FCRE/APL/STD/2017/19.

Funding informations

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or non-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Alexander, N., 2003, Language education policy, national and sub-national identities in South Africa, viewed 12 August 2020, from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.476.2445&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Alexander, N., 2004, 'The politics of language planning in post-apartheid South Africa', Language Problems and Language Planning 28(2), 113-130. https://doi.org/10.1075/lplp.28.2.02ale [ Links ]

Allport, G., 1935, 'Attitudes', in C. Murchison (ed.), A book of social psychology, volume 2, pp. 798-820, Clark University Press, Worcester, MA.

Baker, C., 1992, Attitudes and language, Multilingual Matters, Clevedon.

Cooper, R.L. & Fishman, J.A., 1974, 'The study of language attitudes', International Journal of the Sociology of Language 3, 5-20. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.1974.3.5 [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W., 2015, A concise introduction to mixed methods research, Sage, Los Angeles, CA.

De Klerk, V. & Bosch, B., 1993, 'English in South Africa: The Eastern Cape perspective', English World-Wide 14(2), 209-229. https://doi.org/10.1075/eww.14.2.03dek [ Links ]

De Klerk, V. & Gough, D., 2002, 'Black South African English', in R. Mesthrie (ed.), Language in South Africa, pp. 356-378, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Ditsele, T., 2014, 'Perceptions of Black South African languages: A survey of the attitudes of Setswana-speaking university students toward their first language', Doctoral thesis, Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, T., 2000, 'South Africa: From two to eleven official languages', in K. Deprez & T. Du Plessis (eds.), Studies in language policy in South Africa, pp. 35-110, Van Schaik, Pretoria.

Eagly, A.H. & Chaiken, S., 1993, The psychology of attitudes, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Inc., Orlando, FL.

Eastman, C.M., 1983, Language planning: An introduction, Chandler & Sharp, San Francisco, CA.

Garrett, P., 2010, Attitudes to language, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Garrett, P., Coupland, N. & Williams, A., 2003, Investigating language attitudes, University of Wales Press, Cardiff.

Heine, B., 1992, 'Language policies in Africa', in R.K. Herbert (ed.), Language and society in Africa: The theory and practice of sociolinguistics, pp. 23-35, Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg.

Kloss, H., 1967, Research possibilities on group bilingualism: A report, viewed 12 August 2020, from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED037728.pdf.

Lo Bianco, J. (ed.), 2002, Voices from Phnom Penh, development and language: Global influences and local effects, Language Australia Ltd., Melbourne.

Macucwa, S.T., Ditsele, T. & Makgato, M.M., 2020, 'Using Setswana in business transactions in the clothing industry at the West Rand District Municipality in Gauteng', The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa 16(1), Online. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v16i1.856 [ Links ]

Mann, C.C. & Wong, G., 1999, 'Issues in language planning and language education: A survey from Macao on its return to Chinese sovereignty', Language Problems and Language Planning 23(1), 17-36. https://doi.org/10.1075/lplp.23.1.02iss [ Links ]

Maree, K. (ed.), 2007, First steps in research, Van Schaik, Pretoria.

Mutasa, D., 1999, 'Language policy and language practice in South Africa: An uneasy marriage', Language Matters: Studies in the languages of Africa 30(1), 83-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/10228199908566146 [ Links ]

Mutasa, D.E., 2003, 'The language policy of South Africa: What do people say?', Doctoral thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Noss, R.B., 1971, 'Politics and language policy in Southeast Asia', Language Science 16, 15-32. [ Links ]

Palinkas, L.A., Horwitz, S.M., Green, C.A., Wisdom, J.P., Duan, N. & Hoagwood, K., 2015, Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research, viewed 07 August 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4012002.

Rakgogo, T.J. & Van Huyssteen, L., 2018, 'Exploring the Northern Sotho language name discrepancies in informative documentation and among first language speakers', South African Journal of African Languages 38(1), 79-86. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa, 1996, The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act 108 of 1996), Government Printers, Pretoria.

Smit, U., 1996, A new English for a new South Africa? Language attitudes, language planning and education, Braumüller, Vienna.

Struwig, F.W. & Stead, G.B., 2001, Planning designing and reporting research, Pearson Education South Africa, Cape Town.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Thabo Ditsele

ProfDitsele@outlook.com

Received: 13 June 2021

Accepted: 30 Sept. 2021

Published: 31 Jan. 2022

Appendix 1

Table 1- A1 - Click to enlarge