Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Literator (Potchefstroom. Online)

On-line version ISSN 2219-8237

Print version ISSN 0258-2279

Literator vol.40 n.1 Mafikeng 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/lit.v40i1.1438

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

English as a medium of worship: The experiences of the congregants of a Pentecostal charismatic church in Soweto

Thabisile N. Adams; Anne-Marie Beukes

Department of Languages, Cultural Studies and Applied Linguistics, School of Languages, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This study examines the experiences of the congregants of a Pentecostal charismatic church (PCC) in Soweto regarding the use of English for communication. This particular church is peculiar in that English is its predominant language of religion. This is in stark contrast to many mainline churches (such as the Anglican, Lutheran and Roman Catholic churches) that use indigenous African languages (IALs) in most, if not entire, presentation of church services for black congregants. The curiosity then arises concerning the reasons for the predominant use of English during services in PCCs. The objectives of this study were to find out the general views of black congregants about the English language, how this view may impact on the congregants' view of the use of English within the context of the service and what their preferences about language use in the sermon are, and why. The findings suggest that the congregants view English positively and are receptive to its use in the service, particularly for conducting sermons. In addition, English is seen as an all-inclusive language but notably, not as a language of identity. Based on these findings, strategies for accommodating the diverse language concerns of the congregation were espoused.

Introduction

South Africa is a country of many languages, diverse nationalities and cultures. This diversity is reflected in institutions such as the Christian church. South African Christians find themselves with a range of choices on how they desire to express their Christianity. Bauerle et al. (2012:11) allude to this diversity in the religious domain: 'the diversity of South Africa's churches and religious communities reflects the country's history of immigration and politics, the work of missionaries and the black population's struggle for emancipation'. The Pentecostal church, a branch within the Christian grouping that stems from the broader Protestant denomination, is one such option available to the South African community.

The current study forms part of a larger research project that explored the language of religion in the Pimville church. Its focus is on the relationship between language and religion in the South African context and language use in the conducting of church services and other activities. Studies that have touched on language and religion in this context include Harries (2008), who argues that 'it is helpful not to use it [English] as first language or to run African churches', and Kamwangamalu (2006:91), who states that 'language practices in the family domain, however, suggest that English is gradually replacing the African languages in virtually all spheres, including religion'. English has become a predominant mode of preaching and communication in Pentecostal churches, yet 'little has been written on the history of Black Pentecostals in South Africa' (Anderson & Pillay 1997:227). The aims of this study were: (1) to investigate the views of black congregants of a Soweto-based Pentecostal charismatic church (PCC) (to be called Church A) regarding the predominant use of English in church services, and given that these congregants generally speak indigenous African languages (IALs) at home, and (2) to determine their preferences regarding language use in sermons.

Some work has been conducted regarding the Africanisation of Christianity in other parts of Africa (Harries 2009; Olájubù 2001; Salami 2006), and particularly in Nigeria, a nation that has embraced the Pentecostal model and faith in a significant way. In fact, Ugot and Offiong (2013) state that:

… in Nigeria, Pentecostalism exhibits traits of American Pentecostal influence in their language techniques and concepts. Its popularity has also been aided by tele-evangelism [that] started in the USA and gained popularity in Nigeria. (p. 148)

In this regard, English is incorporated into the ideals and meanings of the indigenous culture where necessary. Albakry and Ofori (2011:517) explore the monolingual use of English and how it is 'code-switched and code-mixed with indigenous Ghanaian languages when Catholics interact in socioreligious settings'. Code-switching is defined as the practice of alternating between two or more languages across sentence boundaries, while code-mixing occurs within sentence boundaries. Woods (2004) studied the relationship between language and religion in Australia's ethnic churches, giving insights into the language(s) that these congregations used during worship, the service, for liturgy, et cetera. Extensive studies have been conducted on the role of language within religions such as Islam and Judaism (Drewes 2007; García-Arenal 2009; Jaspal & Coyle 2010), to the point where Arabic and Hebrew are identified as sacred languages in their respective religions. Sawyer, Simpson and Asher (2001) support the notion by stating that:

… in the case of Islam the Qur'an is traditionally believed to have been composed in an inimitable variety of Arabic in heaven and attempts to translate it into other languages have been strongly resisted by the religious establishment. (p. 3)

However, studies on the Pentecostal movement are not nearly as detailed.

In spite of the scope of research conducted within the Christian religion, and particularly in relation to Christianity and language, limited research has been conducted about the language of religion in black churches in South Africa, and specifically within black PCCs. In addition, within a landscape where the population is predominantly black people, no significant research has been conducted in describing language policy and use in black churches, particularly regarding English. From a language policy, planning, and language management standpoint, Spolsky (2004:31) states that the domain of religious institutions and their language management is 'a field in which study has been ignored in the 20th Century secularisation of western academic fields'; this, therefore supports the place for such a study.

Literature review

Language in the religious domain

Language plays a key role in the religious domain because it is the tool used to preach and teach. Language 'becomes the most important means by which God's faithful can communicate, fellowship or commune with Him and each other' (Ugot & Offiong 2013:148). In Woods' (2004) study on language use within Australia's ethnic churches, two main factors are addressed: firstly, that people use language in different ways so as to enhance how they relate to God, and secondly, depending on the individuals' view of their God, they may choose to use a specific language, or a variety thereof, to demonstrate the nature of this relationship. One may even use a number of languages to various degrees to express this. These factors are greatly influenced by the denomination to which an individual belongs. In addition, the level of intimacy, respect and veneration are addressed as being a factor in the language an individual uses for religious expression. Some, in a display of respect, would choose to use a language or a variety that is considered of a high status, while others may opt to use a less formal variety that shows a level of comfort, intimacy and ease with him.

Language use in the religious domain can often not be separated from how it is used in society, nor can it be separated from the attitudes that are attached to it in the broader community. Venter (1998:23) observes that members of religious institutions 'do not leave either ideological persuasions or social identities at the door'. The beliefs that one has about language, whether positive or negative, are carried into different domains of one's life. He further states that 'language preference is a function of language ideology' (Venter 1998:24). Bamgbose (2000), Myers-Scotton (2006) and Garrett (2010) further support the notion of the importance of language attitudes and ideology and the effects thereof on the language choices made by individuals in various domains.

Language choice in a multilingual context: English as a lingua franca

One of the most common ways of bridging the language gap in a linguistically diverse context is by using a lingua franca. On one hand, a single lingua franca arguably facilitates communication between people of different languages, cultures and backgrounds, while on the other hand it is seen as a danger to other, especially minority, languages.

The literature offers various views about English across the world and in South Africa. In Da Silva's (2008:1) view, English has played multiple roles in South Africa, such as being a neutral language, language of oppression, opportunity, separation or exclusivity, and unification. Furthermore, English within the country has always been a cause of disagreement and a 'combination of both threat and promise' (Da Silva 2008:1).

Kamwangamalu (2007) explores the multifaceted nature of English and describes the language in South Africa as belonging to two concentric circles, which are the Inner and Outer circles. The Inner Circle is the domain of those who use the language as a native language (such as white people of British descent, mixed race people and by the younger generations of Indian South Africans), while the Outer Circle refers to those who use it as a second or third language (these being the black population, the older generations of Indian South Africans, mixed race people and Afrikaners). According to Statistics South Africa (2012), only 2.9% of South Africa's black population speaks English as a first language (thereby assigning it to the Outer Circle for much of the country's black population). However, this does not diminish the importance that the language may have to the majority of black second- or third language speakers as a functional language and lingua franca.

In spite of the prestige of English worldwide, mixed feelings remain regarding the use of English versus IALs among the black South African community. One of the points of contention concerns language, culture and identity. Da Silva (2008) explains this dynamic by remarking that speakers express positive attitudes towards English because of the numerous social and economic advantages that it grants. However, tension is created by the fear of English interfering with one's ethnic and cultural identity. Still others view English as a means to an end and not necessarily as taking the place of their mother tongue; it is merely seen as an additional linguistic resource that can be used as and when needed.

House (2003) distinguishes between a 'language for identification' and a 'language for communication'. A language for identification is defined as a local language that holds a key stake in determining one's identity and tends to define a specific individual or group, while a language for communication is one that is used for transactional and functional purposes (House 2003:560). Furthermore, she argues that using English as a lingua franca (ELF) does not necessarily replace the native tongue because they are used for different purposes. In fact, she believes, ELF 'may stimulate members of minority languages to insist on their own local language for emotional binding to their own culture, history and tradition' (House 2003:561). This suggests that English does not have the power to take over another language; rather, it is the users of the language who determine the power that a language has and what the language represents for them. The same principle is applicable to English in South Africa; for their own purposes, the users of these languages determine what to use the languages for, and how. This argument may explain why congregants at Church A may choose to use English as the main language of communication: that it is a resource in spite of the perception that it is a threat to the IALs.

The 'heart' language

Adams, Allen and Fish (2009) find the use of local languages to be essential for a meaningful engagement with the gospel. They call this the 'heart language' and define it as 'the language spoken in the home' (2009:81). From their perspective, the term is used interchangeably with the concepts 'mother tongue' and 'local language'. In a study conducted among 300 evangelists based in the Muslim world, they sought to investigate the practices that were seen as crucial for fostering evangelical movements in these countries. One of these was the use of the 'heart language'. Results indicate that 'there was a far more likely chance of seeing mature fruit and/or multiplication of communities of faith when the gospel is proclaimed in the medium of the "heart language"' (2009:76).

Aligning himself with Adams et al. (2009), Brown (2009:85) believes that the use of a heart language 'affirms [people's] personal worth and opens hearts and minds to hear the message'. He proceeds to state that while the use of a local language is commendable, it must embrace the vocabulary of the people who use it, as:

… while affirming the people's language can open minds and hearts, rejecting their vocabulary still conveys rejection of their identity and worth. This in turn prompts people to reject both the communicators and their message. (Brown 2009:86)

Brown (2009) also believes that the use of one's mother tongue is essential for the continuity of the faith over generations. Referring to the early church, he indicates that the gospel was shared in the local language in order for common people to understand it. Had it not been so, he believes that 'their knowledge of the biblical faith would have been weak and unsustainable over the generations' (Brown 2009:87). In contrast, the gospel was not presented in the local language in the Middle East, but in the prestigious languages of the day. When this took place, the result was that:

… everyday believers lacked a good understanding of God's Word and were vulnerable to other winds of doctrine. When Islam arose in the seventh and eighth centuries, these Bibleless churches nearly disappeared. (Brown 2009:87)

On the other hand, Luchivia (2012) argues that the 'heart' language, more than necessarily a mother tongue, should be the deciding factor in which language worshippers choose for religious expression. These are 'languages in which issues are better understood' (Luchivia 2012:2). In his Kenyan study based on language use in the church, Luchivia (2012) argues that:

… if people can be presented with God and left to relate to Him directly, they will understand Him better. This happens within a language that captures the listeners' heart and mind which is not necessarily mother tongue for people who are in multilingual contexts. My theory is therefore that people need to be provided an opportunity to hear and share the message of God using languages of the heart. This is language that goes beyond mother tongue. I suggest that we must look beyond the question of mother tongue, and ask what other factors influence the individuals' choice. (p. 2)

Here, Luchivia (2012) recognises the fact that one's mother tongue is not the only resource that one has at his or her disposal in the religious context. In addition, it also accommodates the possibility that individuals may understand concepts or ideas in more than just one language, and more specifically, their mother tongue. He further clarifies by saying that people may understand and express certain concepts in each language slightly differently, and that the availability of many languages in one's repertoire helps them to do this.

Furthermore, Luchivia (2012) explains his experiences in evangelising and preaching to people and states how he found that even with a so-called 'foreign' language, one was able to reach out to others and impact them with the gospel. In fact, in Kenya English is no longer seen as a foreign language, but as a second or third mother tongue. As it is almost impossible to keep languages apart with the advent of globalisation, rather than see this as a disadvantage, it may be used as an opportunity to tap into the knowledge contained in this language.

In Luchivia's (2012) view, there are other ways in which people's languages can be accommodated when in a multilingual congregation:

In order to promote people's cultural expressions in a way that is consistent with God's Word, some churches schedule times when songs are sung in several languages, and cultural days and other cultural activities are organised. This leads people to appreciate their own and other peoples' cultures. It also equips people to be witnesses among their own kin who may not hear the message any other way. (pp. 25-26)

In this way, all people of whatever language are able to access God and his teachings better.

Lastly, Luchivia (2012) reiterates the concept of using context as a tool to measure which language would be appropriate at what time. When this is done, language is able to serve its function in a more positive and productive manner.

A brief description of Church A

Church A was established in 1984 as an outreach branch of a well-known South African charismatic ministry. From an initial membership of 35 people, it has grown to an estimated 30 000-plus membership across 14 different satellite churches in South Africa. For this study, the researcher focused on the 'mother church', based in Pimville, Soweto. This branch, according to an interview with Pastor M on 12 May 2014, has a membership of over 20 000; this number is not based on attendance, but on the decision forms that members fill in when they decide to become members of the church.

The sermons are conducted mainly in English, and IALs are often incorporated into the service by way of code-switching and code-mixing. This is the same for other components of the service (announcements, prayers, etc.).

Pastor M estimates that the middle class makes up 20% - 30% of the congregation, 5% by the so-called 'big-earners' and 75% by the working class. He further estimates that young people make up 55% of the congregation (below 40 years), while 45% consists of older people.

Methodology

Data were collected from the congregants of the church over a period of 2 months (March-May 2014). The tool used was a structured questionnaire consisting of both open- and close-ended questions. Some of the questions asked made use of a four-point Likert scale. The decision to use a four-point scale was made based on the fact that a four-point scale 'forces a decision' and because a good questionnaire 'uses mostly closed questions, often with a four-point scale' (Goddard & Melville 2004:48). Moreover, in the pilot study for this research (where a five-point scale that included the category 'neutral' was used), many respondents selected the 'neutral' option. In the researcher's view, this was not helpful in extracting information because the response can be viewed as being ambiguous in nature and lends itself less to interpretation. Again from the researcher's perspective, this was viewed as a 'safe' option for respondents. However, even in spite of attempts to 'force a decision' in the final study, a few respondents still indicated answers that fell between the given categories.

Participating criteria were as follows: church members must be over the age of 18 and have attended services for at least 6 months. Efforts were made to distribute the questionnaire to respondents across a wide range of age groups (18-29, 30-39, 40-49,50-59, and 60 years and above) in order to obtain a representative sample. Respondents who filled in the questionnaires were provided with a covering letter containing information about the study. They were also required to sign this letter to indicate consent. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured, and all participants were made aware that participation was voluntary. Of the 250 questionnaires distributed, 72 were completed and returned.

Analysis of results

Sociolinguistic profile of respondents

The majority of the respondents were women (66.7%), mostly below 40 years (72.1%). Only 2% of the respondents did not go up to matric level, and 67% had completed a post-matric qualification. The kind of jobs held by the respondents can be considered as more of white-collar than blue-collar occupations (e.g. auditing, teaching and marketing). In addition, these professional positions often require post-matric qualifications or on-the-job training. This information suggests that the congregation was well educated and accustomed to a working environment that often requires the use of English, as most workplaces utilise English as a medium of communication.

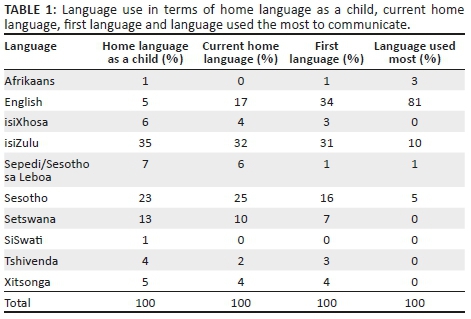

Table 1 presents the home language (defined as the language participants most commonly use in the home environment) respondents spoke as a child, their current home language, their first language (the language that respondents felt that they could best communicate in), as well as the language that they used the most to communicate with others daily.

Overall, the respondents indicated an increase in the current use of English in the home together with an IAL as compared to their home language as a child, hence the 13% increase in the use of English. This may be attributed to increased respondent interaction with various domains that require the use of English, which, in turn affects the language spoken in the home.

Table 1 also shows that English is ahead in terms of individual percentage of first language speakers (34%), followed closely by isiZulu with 31%. English showed a significant increase in comparison to its use as a first language, with 81% of the respondents saying that this is the language they used the most daily. The popular use of English could be attributed to increased contact with the language in educational institutions, workplaces, the need for a lingua franca in the midst of a multilingual and cultural society, as well as media sources. All these translate into a significant preference or need for using English as a language of communication. In addition, with English being the language participants used the most, 65% of the respondents who indicated that they communicate best in an IAL are, in fact, not using them. The dominant use of English among the respondents reflects the general hegemonic position of English in the everyday life of the church's congregation, even when it is not the preferred or most comfortable language of expression.

General attitudes towards English

On a Likert scale, the respondents were asked to indicate their general attitudes towards English (see Table 2).

According to Table 2, most of the respondents agreed that English was used as a lingua franca (Statement 2 with 94%) and that it was a prominent international language of contact (Statement 3 with 92%). As a language of unity, 69% agreed on this characteristic (Statement 7). However, English (Statement 11 with 53%) was not considered a major threat to the IALs. Notwithstanding current views that English 'creates barriers as much as it presents possibilities' (Pennycook 2011:515), the respondents did not regard it as a language of division (Statement 4 with 88%). This may be a case of when the language benefits a group of people, they may not see it as being divisive, particularly if they disregard the fact that there may be those who are not proficient in the language. Statements 5, 6, 8 and 9 also show that respondents perceived English as not being a sign of success and intelligence, nor as the language of successful people. This is in contrast to the general views on English expressed by scholars (Bangeni & Kapp 2007; Da Silva 2008; Prah 2006), who argue that English is a language of upward mobility, success and a good education.

The results indicated that the respondents generally viewed English in a positive light. The strength of English in a multilingual and cultural PCC congregation arguably lies in the fact that it serves as a lingua franca during church services, and that it is useful for international contact. Other reasons espoused for the positive view of English are that the language is seen as promoting national unity, much like the IALs. However, many of the respondents did not think of English as being part of their identity (66%), and rather viewed the IALs as playing this role.

Respondents' views on English as used in Church A

On a Likert scale, the respondents were asked to indicate their general attitudes towards the use of English in the church (see Table 3).

Statement 1 indicates that congregants were open to a common language in the church (70%), although 80% did not agree that only one language should be used (Statement 2). This suggests the participants' recognition of the value of multilingualism: they saw the practicality of having a common language that all can understand, but did not feel that a one-language policy should be rigid should the need for the use of other languages in that domain arise. Statements 3 and 4 required self-reporting and showed that the respondents strongly believed that they had the linguistic ability required to understand the sermon (100% and 97%, respectively). Here, self-reporting could have contributed to such a high percentage, as people would generally not readily admit to not being able to understand or having ability in something, especially in a highly prestigious language such as English. This data may be seen as a limitation and may obscure the reality of what respondents actually understood in the sermon. Considering that it is not necessarily easier to understand the sermon when it is in English (Statement 7 with 52%), the suggestion is that the message is enhanced when different languages are utilised, and that each language adds a layer and texture of meaning.

The respondents strongly expressed that they would not attend a service that was only presented in an IAL if they had the choice to (Statement 5 with 96%). This supports results in Table 1, indicating that they would rather use the language that they communicated in the most (English) than the language they understood the best (IALs). In addition, Statement 6 shows that 55% of the congregants believed that using only an IAL in the service would cause too much division. Their response confirms the firm lingua franca status of English in this church: even though there is an appreciation for the IALs, domain and functionality play a strong role in determining the language use. English played a more prominent role in the general spiritual experience of this congregation and was deemed the most convenient solution to a domain that is diverse in IALs. This is made clearer by Statement 8, where 73% of the respondents agreed that English is the common language that should be used in the church. Again, this entrenches the important instrumental value of English in respondents' eyes.

Respondents' views on reasons for the dominance of English at Church A

Responses to the question 'what do you think is the reason for the predominant use of English in sermons at this Pentecostal charismatic church?' again point to the utilitarian role of English as a common, understandable language that is used to cater to a multilingual, multicultural and multigenerational audience. Comments to this effect were the following:

'Because we have different race groups and different indigenous languages, for better understanding English is predominant so that there is a better understanding among the congregants. English is easily understood even for a Grade 1 learner compared to people having to understand a particular language.' (Participant 1, male, teacher)

'English is an international language and the language is understood by the majority of the congregation. Indigenous languages are too sub-divided and it makes it difficult to cater for all the indigenous languages.' (Participant 48, female, market analyst)

'[This Pentecostal charismatic church] is an international church, which always get[s] visited by people from all nations. English help[s] to reach common ground.' (Participant 32, male, unemployed)

'[It] saves time; no need for an interpreter. We understand, even elderly people educate even those who are not so educated in English.' (Participant 37, female, nurse)

Some congregants linked the use of English in the service to the level of education and class levels of the congregants:

'Most people who attend there are educated and have better understanding of the English language.' (Participant 9, female, business development manager)

'The more free we are, the more access Africans have to what was just [for] whites only previously. Being that the church is predominantly young and middle class, the young middle class communicate in English more.' (Participant 56, female, recruitment consultant)

In addition, another respondent expressed the view that the church caters for people who depend on English to communicate:

'I think there is a number of people who now attend [this Pentecostal charismatic church] who mostly rely on English as a form of communication.' (Participant 15, female, retail assistant)

Finally, another congregant focused on the usefulness of the language to the pastors in particular:

'It would be difficult for the pastor to accommodate all official languages of RSA within his/her sermon.' (Participant 53, male, intern consultant)

As indicated in the above quotes, most of the respondents stated that English is a beneficial, unifying, convenient and all-inclusive language resource. It is also perceived as accommodative, easy for everyone to understand, eliminates the need for an interpreter and removes tribal and cultural barriers.

Furthermore, English is also found to be useful for accommodating international visitors who are diverse in language and race. This suggests that the church has positioned itself to be international in worship rather than being limited to local worshippers. From Ruiz's (1984) 'language-as-resource' perspective, the advantage of easing tensions between minority and majority groups (in terms of first language speaker size) is evident here (in this case, locals and international visitors who are in search of a place of worship). Respondents who use both numerically less dominant languages in Soweto (e.g. Xitsonga [8.9%] and Tshivenda [4.5%]) and more dominant ones like isiZulu and the Sotho-Tswana group of languages (37.1% and 33.5%, respectively) (https://census2011.adrianfrith.com/place/798026) have indicated that English is helpful in solving the 'which-language-to-use?' dilemma. Largely, English has become the middle-ground language of sorts. This is in spite of the fact that only 2.34% of Soweto's population speaks English as a home language. Essentially, English may be a language that belongs to the Outer Circle (according to Kamwangamalu 2007), but it retains its value as a prestigious and useful lingua franca.

Finally, some respondents believe that using English benefits not only the audience, but also the pastor. Although a small number (1.5%), it indicates congregants' consciousness of the challenges that a diverse audience may pose to the pastor. This all-inclusive nature of ELF strengthens its position in the eyes of the respondents as the ideal language to use. The reasons espoused for the dominance of English challenge the idea that the church seems to be mainly for educated, well-off people, but is also for people who are unified in worship and whose aim is to have access to worship in a comfortable, understandable and unifying language, whatever the social status or level of education. This goes against the belief held by many non-members that the church is for well-resourced people who drive fancy cars and speak English. Pastor M disputed this by estimating that the middle class made up 20% - 30% of the congregation, the so-called 'big-earners' 5% and the working class 75%.

Views of respondents on preferred language for sermons

The question 'which language would you prefer the sermon at this church to be in?' was asked to determine whether members of the congregation would consciously choose English and if so, why they did. A majority of respondents (62%) selected English only as the language of choice, while the rest gave a mixture of both English and an IAL as the preferred choice (27%). The clear preference for English is congruent with Statement 8 in Table 3, where 73% of the respondents expressed that English should be the common language in the church. None of the respondents opted for an IAL only as the preferred language. This aligns with Statement 5 in Table 3, where 96% of respondents said that they would not attend a service if that was in an IAL only.

Some of the responses indicating English as the preferred choice were as follows:

'English. I'm able to understand clearly what is being preached as my level of understanding, e.g. Sesotho does not match that of English.' (Participant 25, female, call centre team leader)

'English because I would love for everyone to receive revelation and enlightenment.' (Participant 3, female, recruitment officer)

'English because some of the words in other languages I don't understand them which will make it difficult for me understand the point the pastor/bishop is trying to prove/make.' (Participant 61, male, unemployed)

'English is fine because then if one chooses an African language how many will understand?' (Participant 11, female, unemployed)

'English language. I believe it is the most common language spoken worldwide. If an Indigenous language is used, the question would be which one and it will also divide the church whereby some people will abscond until their language is spoken. So for peace sake and commonality English is the best language to use.' (Participant 1, male, teacher)

On the other hand, those who favoured a mixture of English and IALs said the following:

'A mixture of them ([isi]Zulu, [Se]tswana, Sepedi, English, etc.) to accommodate everybody.' (Participant 49, male, market analyst)

'English and a mixture of African languages. Some concepts are better expressed in certain languages. Limiting the language use to only one takes away from the meaning of the sermon.' (Participant 57, female, lecturer)

'English and isiZulu. We need to preserve our languages.' (Participant 64, male, mechanical engineer manager)

'Switching as is done is ok, the mix of languages helps us to identify and feel a sense of belonging at church.' (Participant 55, male, fleet manager)

The findings suggest that the congregation had a strong preference for English: the majority of those who responded (62%) selected English as the single language of choice. This is despite the fact that the church is dominated by home language speakers of the IALs (see Table 1). The finding is not surprising, considering the educational level of the participants, and consequently their duration of exposure to English in their education. The preference for English might also be motivated by the fact that English is a language of convenience for a congregation with diverse IALs, as it facilitates the understanding of sermons to all congregants. The congregants viewed English as a unifier and cement of the church and a means of retaining congregants of diverse languages. English is believed to be accommodative and provides easy access to the sermon.

Of the respondents, 27% preferred that the sermon should be a mixture of both English and an IAL. Of these, the IALs that were chosen by most respondents came from the Nguni (specifically isiZulu) and Sotho-Tswana (Sesotho, Sepedi and Setswana) language groups. This indicates that within IALs, there are languages that are viewed as being dominant. Soweto's 2011 Census results indicate that 37.1% of the area's population use isiZulu as their home language, while the combined percentage of the Sotho-Tswana language group was spoken by 33.5% of the population (https://census2011.adrianfrith.com/place/798026). Results on respondents' first languages in Table 1 indicate that iZulu stands at 31%, while the combined figure for the Sotho-Tswana language group comes to 24%. Therefore, it can be presumed that a majority of the congregation would be in a position to understand the sermon if the church was to combine the use of these language groups with English (34%). None of the respondents opted for an IAL only as the preferred language for the sermon. These findings support Kamwangamalu's (2006:91) observation that English is gradually replacing the African languages in virtually all spheres, including religion. While English is still a practical choice, the IALs fill other gaps as well that go beyond practicality. It shows the importance of IALs with regard to accommodating the audience, linking them with identity and ease of expression and comprehension.

Language accommodation strategies

There was a significant difference in the results between respondents who indicated a preference for English only (62%) and those who showed a preference for a combination of English and an IAL (27%). Although the number of those who preferred English was higher, the presence of people who would like to see the languages combined was significant enough to take note of. It indicates that there are congregants who may rely on the IALs for a number of factors, such as comprehension, social cohesion and identity.

Although the number of people who indicated preferring a combination of English and an IAL is marginal, it is still important for their needs to be catered for. This can be done by means of providing interpreting services. According to Pastor M, in the early years of the church, English was used as the main language, with interpreting interchangeably taking place into isiZulu, Sesotho and Setswana from month to month. The IALs were consciously chosen based on the popularity of the languages within the demographics of the congregation and not because these were perceived as 'better' than other IALs. When the opportunity arose to have their Sunday services aired by the public broadcaster, the South African Broadcasting Corporation, Pastor M stated that they were requested to use only English 'according to the broadcaster's policy'. This practice of using one language has continued, even though the broadcasting of services has stopped. It could prove beneficial for the church to re-introduce this service during the current Sunday service. Alternatively, they could create a separate service that interprets the sermon into an IAL.

A second alternative to manage the multilingual situation at the church is to continue encouraging the current use of code-switching and code-mixing during the service. As Pastor M explained, because most of the congregants are from a metropolitan or township environment, they are familiar with English and the hybrid township languages spoken in their surroundings. The church used these languages as well as English to relate to the members, which the church believed is beneficial in engaging with people at their level and aided them in understanding the content of the message in a language(s) that they could relate to.

Conclusion

With the language policy and planning perspective as its departure point, this study aimed to establish the experiences of the congregants of a black Pentecostal charismatic church in relation to the use of English as a medium of worship. The findings of this study indicate that English remains a dominant mode of conducting services in this church. However, the findings also indicate that a middle ground can be found by using a combination of English and IAL.

A significant degree of linguistic tolerance and acceptance of diversity in this congregation indicates that it is receptive to people from every demographic. This church's multilingual nature could be best served by introducing language policy measures to accommodate the congregation's language needs. In this regard, the re-introduction of interpreting services and, or code-switching during services may be considered. This approach not only appeals to the languages that the congregation may speak in addition to English, but also allows the audience to be engaged on a social and identity level. This would signal that language is not only a matter of the head, but is also strongly attached to the heart. It is therefore important to use these 'heart languages' to aid both understanding and cohesion to the church body. There is clearly room for integrating selected and applicable IALs in church services and worshipping.

This research has attempted to fill a gap in our understanding of the relationship between language and religion in the multilingual urban context. It has uncovered some of the issues related to the use of English as a medium of communication in a Sowetan PCC. These issues may raise awareness of the impact of the use of English in its services. It may also sensitise church authorities to the merits of overt language policy and planning in order to meet its congregants' language needs.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contribution

T.N.A. conducted the research as part of her master's study at the University of Johannesburg, with A.-M.B. as the supervisor. T.N.A. prepared the first draft of this article with subsequent conceptual and editorial input from A.-M.B., which resulted in the final draft.

References

Adams, E., Allen, D. & Fish, B., 2009, Fruitful practices: What does the research suggest? Seven themes of fruitfulness, viewed 28 August 2014, from www.ijfm.org/PDFs_IJFM/26_2_PDFs/75-81_Seven%20Factors.pdf

Albakry, M.A. & Ofori, D.M., 2011, 'Ghanaian English and code-switching in Catholic churches', World Englishes 30(4), 515-532. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2011.01726.x [ Links ]

Anderson, A. & Pillay, G., 1997, 'The segregated spirit: The Pentecostals', in R. Elphick & R. Davenport (eds.), Christianity in South Africa: A political, social and cultural history, pp. 227-241, David Phillip Publishers, Claremont, CA.

Bamgbose, A., 2000, Language and exclusion: The consequences of language policies in Africa, Lit Verlag, Hamburg.

Bangeni, B. & Kapp, R., 2007, 'Shifting language attitudes in linguistically diverse learning environment in South Africa', Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 28(4), 253-269. https://doi.org/10.2167/jmmd495.0 [ Links ]

Bauerle, P., Dickow, H., Hanf, T. & Møller, V., 2012, Religion and attitudes towards life in South Africa: Pentecostals, charismatics and reborns, Nomos, Baden-Baden.

Brown, R., 2009, 'Like bright sunlight: The benefit of communicating in heart language', International Journal of Frontier Missiology 26(2), 85-88. [ Links ]

Da Silva, A.B., 2008, South African English: A sociolinguistic investigation of an emerging variety, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

Drewes, A.J., 2007, 'Amharic as a language of Islam', Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 70(1), 1-62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0041977X07000018 [ Links ]

Frith, A., n.d., Soweto, viewed 17 April 2018, from https://census2011.adrianfrith.com/place/798026

García-Arenal, M., 2009, 'The Religious identity of the Arabic language and the affair of the lead books of the Sacromonte of Granada', Arabica 56(6), 495-528. https://doi.org/10.1163/057053909X12544602282277 [ Links ]

Garrett, P., 2010, Attitudes to language, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Goddard, W. & Melville, S., 2004, Research methodology: An introduction, Juta & Company Ltd, Landsdowne.

Harries, J., 2008, Overcoming 'dependency' in the African church: The African languages, viewed 11 August 2011, from http://www.jim-mission.org.uk/articles/overcoming-dependency-in-the-african-church.html

Harries, J., 2009, 'The name of God in Africa and related contemporary theological, development and linguistic concerns', Exchange 38(3), 271-291. https://doi.org/10.1163/157254309X449737 [ Links ]

House, J., 2003, 'English as a lingua franca: A threat to multilingualism?', Journal of Sociolinguistics 7(4), 556-578. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2003.00242.x [ Links ]

Jaspal, R. & Coyle, A., 2010, '"Arabic is the language of the Muslims - That's how it was supposed to be": Exploring language and religious identity through reflective accounts from young British-born South Asians', Mental Health, Religion and Culture 13(1), 17-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670903127205 [ Links ]

Kamwangamalu, N.M., 2006, 'Religion, social history and language maintenance: African languages in post-apartheid South Africa' in T. Omoniyi & J. Fishman (eds.), Explorations in the sociology of language and religion, pp. 86-96, John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam.

Kamwangamalu, N.M., 2007, 'One language, multi-layered identities: English in a society in transition, South Africa', World Englishes 26(3), 263-275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2007.00508.x [ Links ]

Luchivia, J.O., 2012, 'Contextualised language choice in the church in Kenya', Doctoral dissertation, Fuller Graduate School, CA. [ Links ]

Myers-Scotton, C., 2006, Multiple voices: An introduction to bilingualism, Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA.

Olájubù, O., 2001, 'The influence of Yorùbá command language on prayer, music and worship in African Christianity', Journal of African Cultural Studies 14(2), 173-180. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696810120107113 [ Links ]

Pennycook, A., 2011, 'Global Englishes', in R. Wodak, B. Johnstone & P. Kerswill (eds.), The SAGE handbook of sociolinguistics, pp. 513-525, SAGE, London.

Prah, K.K., 2006, Challenges to the promotion of indigenous languages in South Africa, The Center for Advanced Studies of African Society, Cape Town.

Ruiz, R., 1984, 'Orientations in language planning', NABE Journal 8(2), 15-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/08855072.1984.10668464 [ Links ]

Salami, O., 2006, 'Creating God in our image: The attributes of God in the Yoruba socio-cultural environment', in T. Omoniyi & J. Fishman (eds.), Explorations in the sociology of language and religion, pp. 97-117, John Benjamins Publishing, Amsterdam.

Sawyer, J.F.A., Simpson, J.M.Y. & Asher, R.A., 2001, Concise encyclopaedia of language and religion, Elsevier Science, UK.

Spolsky, B., 2004, Language policy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Statistics South Africa, 2012, Census 2011 Census in brief, Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

Ugot, M.I. & Offiong, O.A., 2013, 'Language and communication in the Pentecostal church of Nigeria: The Calabar axis', Theory and Practice in Language Studies 3(1), 148-154. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.3.1.148-154 [ Links ]

Venter, D., 1998, 'Silencing Babel? Language preference in voluntary associations - Evidence from multi-cultural congregations', Society in Transition 29(1-2), 22-39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10289852.1998.10520143 [ Links ]

Woods, A., 2004, Medium or message? Language and faith in ethnic churches, Multilingual Matters, Clevedon.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Thabisile Adams

tadams@uj.ac.za

Received: 11 Aug. 2017

Accepted: 08 Oct. 2018

Published: 27 Feb. 2019