Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Psychiatry

On-line version ISSN 2078-6786

Print version ISSN 1608-9685

S. Afr. j. psyc. vol.25 n.1 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v25i0.1372

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

First-episode psychosis and substance use in Nelson Mandela Bay: Findings from an acute mental health unit

Yanga ThunganaI, II; Zukiswa ZingelaI, III; Stephan van WykI, III

IDepartment of Psychiatry and Behavioural Sciences, Walter Sisulu University, Mthatha, South Africa

IIAcute Mental Health Care Unit, Dora Nginza Hospital, Bethelsdorp, South Africa

IIINelson Mandela Academic Hospital, Mthatha, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Use of psychoactive substances is a common finding in studies on first-episode psychosis (FEP), and this has prognostic implications. We know very little about psychoactive substance use (SU) among patients with FEP in the Eastern Cape province (EC) of South Africa (SA0).

AIM: The study seeks to determine SU prevalence and associated features among inpatients with non-affective FEP in an acute mental health unit (MHU) in Nelson Mandela Bay, EC.

SETTING: Researchers conducted a retrospective clinical file review of a 12-month admission cohort of patients with FEP, without a concurrent mood episode, to the Dora Nginza Hospital MHU. Information collected included SU history, psychiatric diagnoses, and demographics. Data were then subjected to statistical analysis.

METHODS: Researchers conducted a retrospective clinical file review of a 12-month admission cohort of patients with FEP, without a concurrent mood episode, to the Dora Nginza Hospital MHU. Information collected included SU history, psychiatric diagnoses and demographics. Data were then subjected to statistical analysis.

RESULTS: A total of 117 patients (86 [73.5%] males; 31 [26.5%] females) aged 18-60 years (mean 29 years) met the inclusion criteria. After controlling for missing information, 95 of 117 (81.2%) patients had a history of active or previous SU, 82 of 90 (91.1%) were single and 61 of 92 (66.3%) were unemployed. A significant association was found between SU and unemployment (p < 0.001), as well as male sex (p < 0.001). The most common substances used were cannabis (59.8%), followed by alcohol (57.3%) and stimulants (46.4%).

CONCLUSION: In keeping with national and international literature, the results of this study showed a high prevalence of substance use in South African patients with first-episode psychosis. The high prevalence of lifetime substance use in this cohort compared to previous studies in South Africa requires further investigation and highlights the urgent need for dual diagnosis services in the Eastern Cape province.

Keywords: substance use; first-episode psychosis; dual diagnosis; cannabis use; polysubstance use.

Introduction

The use of psychoactive substances is a common finding among patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP).1,2,3,4 Several studies report that psychoactive substance use (SU) has negative prognostic implications for short- and long-term outcomes of FEP.5,6,7,8,9 Other studies report that FEP associated with SU is more likely to be acute in onset with a shorter period of untreated psychosis, although patients are more likely to be admitted involuntarily at first psychiatric contact.7,10,11 The reported close relationship between SU and emergent psychosis suggests a possible causal link, which has highlighted the importance of early intervention for SU as a way of improving outcomes in FEP.12,13

The prevalence of SU among patients presenting with FEP ranges from 30% to 75% across studies and countries.1,9,14,15,16 The wide variation is possibly because of a combination of methodological inconsistencies, as well as cultural and environmental differences between countries, especially regarding the availability of illicit substances.16 The types of substances used by people with FEP vary across studies, but cannabis and alcohol tend to be the most frequently reported.2,15,17,18

In South Africa, the prevalence of alcohol and other drug use disorders is high, with males having higher rates than females, but the gender gap has been narrowing over the last decade.19,20,21 Alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs - among them cannabis and methamphetamine - are the most commonly used substances, with a varying level of use between men and women.22,23 Studies that were conducted in Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces have documented high co-occurrence of substance use in individuals with mental disorders.24,25,26,27 The findings from other provinces are not easily generalisable to the Eastern Cape province as the samples differ in ethnicity and socio-economics.

Despite the strong association between substance use and FEP, the researchers could not find any published study on the topic specific to the Eastern Cape (EC) province of South Africa (SA).

Study aims

The primary aim was to determine the prevalence of SU among inpatients with non-affective FEP on an acute mental health unit (MHU) in Nelson Mandela Bay (NMB), EC. Secondary aims were to identify the predominant substances, as well as clinical and demographic associations.

Study design

The researchers conducted a retrospective, descriptive study of a 12-month cohort of patients admitted for non-affective FEP to a 35-bed acute MHU in Dora Nginza Hospital (DNH), which is a large regional government hospital in NMB.

Method

Procedure

The first author identified all patients admitted to the MHU between 01 November 2016 and 31 October 2017 and systematically scrutinised all available clinical files. Selection criteria were applied, namely: (1) admission for a first-in-lifetime psychotic episode, (2) ages between 18 and 60 years and (3) the simultaneous absence of an episode of a DSM-5 bipolar or major depressive disorder. Clinical files from the inclusion group were then subjected to a data extraction exercise.

Sample

A total of 1481 patients were admitted to the MHU during the 12-month study period. The multidisciplinary team evaluated all patients. For the study, only individuals with non-affective FEP were included. FEP was defined as individuals with psychosis receiving medical or psychological treatment for the first time and affective symptoms not meeting criteria for a mood disorder using DSM-5 28 diagnostic criteria. A total of 271 patients were identified from the admission register to have FEP. Of those, 154 were excluded because of missing case files, not meeting age criteria, having confirmed previous episodes or affective psychosis. The final sample consisted of 117 patients.

Data collection

To ensure consistency, a single researcher captured all data using an anonymised data sheet. Information gathered from clinical files included SU history, physical and psychiatric diagnoses, education and other relevant demographics. SU was defined as the use of any psychoactive substance, whether by evidence from medical history or drug testing, and irrespective of time frame, quantity or usage pattern. Nicotine, as well as the non-problem use of alcohol, and psychoactive medications (over-the-counter or prescribed) were excluded.

Problem use of alcohol or medication was taken to mean progressive usage escalation, withdrawal symptoms, cravings, deliberate attempts at discontinuation, detrimental effects on health (e.g. alcohol blackouts and delirium tremens) or negative impact on functioning (relationships, work, education and substance-related legal problems). Current SU meant the use of substance within the last 3 months. Both point-of-care urine drug screening tests and laboratory tests were accepted as evidence of current SU. The urine drug test used on the MHU was a 6-drug immunoassay, which tested for cannabis (delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol), amphetamine (AMP), methamphetamine (MAMP), cocaine, methaqualone and opiates.

Data analysis

All data were entered into a single database. Descriptive statistics analysis was performed using frequency tables, proportions, means and standard deviations (s.d.). For inferential statistics, cross-tabulation with the chi-square (X2) or Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables. Stata 13 was used for all the statistical analysis, and Excel 2017 was used for drawing up the graphical representation of the data. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Consent to conduct the study was obtained from Walter Sisulu University - Human Research Committee, Eastern Cape Department of Health and institutional managers at Dora Nginza Hospital.

Results

Demographics

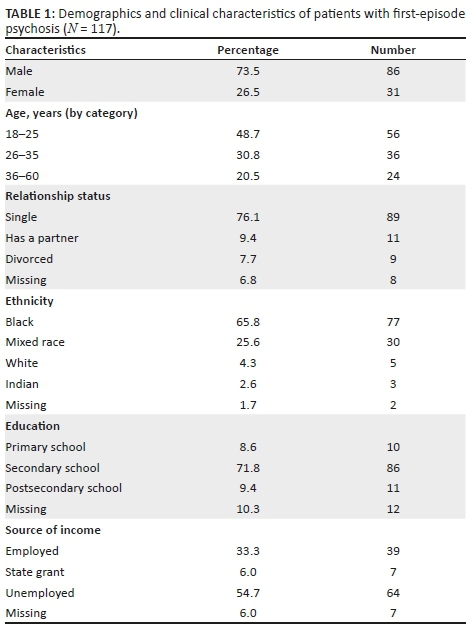

Of the total sample (N = 117), the majority were male (n = 86, 73.5%), black (n = 77, 65.8%), single (n = 89, 76.1%) and unemployed (n = 64, 54.7%). The racial breakdown of the 117 patients in the analysis was similar to that of the catchment population.29 The male to female ratio in the study was 2.8:1 compared to that of the catchment area (1:1.1).29 The age range of the 117 participants was between 18 and 60 years, with a mean of 28.88 years (s.d. 10.63). The majority of participants had some form of high school education (n = 86, 71.8%), but only a few had a higher level of education (n = 11, 9.4%). Most were brought to the hospital by their families, with a large number needing help from the South African Police Services (see Table 1).

Clinical diagnosis

The majority of participants were assessed to have a substance-induced psychotic disorder (n = 51, 43.6%), followed by primary psychotic disorders (n = 30, 25.6%), psychotic disorder because of a general medical condition (n = 24, 20.5%) and a number with an unspecified psychotic disorder (n = 12, 10.3%). The most common general medical conditions were HIV infection (58%) and epilepsy (25%).

Substance use

Of the 117 participants, 116 had documented substance history. Of those with documented substance history, 81.9% (n = 95) had a lifetime history of substance use. Cannabis was the most commonly used substance (n = 70, 59.8%), followed by alcohol (n = 67, 57.3%), stimulants (n = 52, 46.4%), mandrax (n = 14, 12%) and opioid (n = 8, 6.8%) (Figure 1). More participants were still actively using substances (cannabis n = 66, 94.3%, alcohol n = 62, 92.5% and methamphetamines n = 42, 93.3%) with only a few who had discontinued substances (5.7% cannabis, 7.5% alcohol and 6.7% methamphetamines).

There were more males (82.1%) with lifetime use of substances than females (17.9%), and this dissimilarity was significant for all substances combined (p < 0.001). The difference in sex prevalence was also specifically significant for cannabis (males 90% vs. females 10%; p < 0.001), MAMP (males 84.4% vs. females 15.6%; p = 0.04) and for alcohol (males 77.6% vs. females 22.4%; p < 0.001).

The use of cannabis and MAMP was most prevalent among patients aged 25 years or younger (cannabis mean 25 years; 95 % CI 23.89-26.54; p = 0.045 and MAMP mean 24 years; 95% CI 22.5-25.2; p = 0.001). In contrast, problem alcohol use was more prevalent above 25 years (mean age 29 years; 95% CI 26.7-31.6; p = 0.02). Thirty (31.6%) of the 95 patients with a history of SU had used a single substance, compared to 65 (68.4%) patients who had used more than one substance. Thirty individuals (31.6%) had used two substances, and 35 (36.8%) used three or more substances in their lifetime. The most common combinations were: cannabis-alcohol-MAMP (23.1%), cannabis-alcohol (21.5%) and cannabis-MAMP (18.5%). The average use was 2.2 substances per individual (s.d. 1.1).

Urine drug screening was done in only 68 (58.6) of the 116 patients for whom information on SU was recorded. Of the urine screening tests done, positive tests were for cannabis (60.3%), methamphetamine (26.1%), opiates (10.4%) and cocaine (9.2%). All cocaine and opiate users reported active use, and they all tested positive as well.

Significantly, 55 of the 64 (85.9%) patients who were unemployed had a positive substance use history (p < 0.01). There was no significant association between race and substance use (p = 0.12) nor between the level of education and substance use (p = 0.24).

Discussion

Our study showed a very high prevalence of substance use (81.9%) in inpatients with FEP who were admitted to the Dora Nginza Mental Health Unit. There were 117 participants with FEP, and 95 (81.2%) of them had used at least one substance group, currently or in the past. This result is higher than published data on substance use rates (30% - 75%) in FEP.1,14,15,16,30 This could be because of a combination of factors. Firstly, this could be sampling bias because of the inclusion of patients with both current and lifetime history of substance use. Secondly, this could be because of the perceived rising prevalence of substance use in the area. A study conducted in KwaZulu-Natal in patients with psychotic disorders showed that only 10% had no lifetime history of substance.27

In our study, cannabis was the most commonly used substance (59.8%), followed by alcohol (57.3%) and methamphetamines (40.2%). The result is in keeping with many studies which show cannabis and alcohol to be the most commonly used substances in FEP.1,5,14,26 The lifetime history of methamphetamines use was higher in our study than previously published data.15,26,31 This result could be because of the higher prevalence of substance use in this study sample.

On average, those with cannabis use were younger (25 years) than those with alcohol use (29 years). This is comparable to other studies which show that patients using cannabis presented with a psychotic disorder at an earlier age than those with alcohol use history.30,32,33 In our study, 68.4% of those with substance use history had used more than one substance group and most had used three or more substances in a lifetime. Findings of a high prevalence of polysubstance use in FEP have been reported in other studies.2,34

Urine drug testing seemed to have been driven by positive substance use history in this study. For example, 59.8% of participants were found to have a documented use of cannabis, and 58% of the study sample had a cannabis urine drug test. It was 60.3% and 26.1% who had positive results in those tested for cannabis and methamphetamines, respectively. Patients admitted to the MHU spend approximately two to three days in the emergency unit before being transferred to the unit, and this could explain the lower positive rates of methamphetamine tests compared to cannabis tests.

Of the 95 participants who used substances, the majority were male. Furthermore, being a male was strongly associated with substance use (p < 0.001), specifically cannabis use (p < 0.001) and methamphetamine use (p = 0.04). Other studies have also shown a higher proportion of male patients among those who use substances in first-episode psychosis.35,36,37,38

Statistics for EC drug treatment centres show that alcohol is a commonly used substance (45.2%) followed by cannabis (17.6%) and methamphetamine (16.2%), with average ages of 41 years for alcohol, 20 years for cannabis, and 24 years for metamphetamine.39 The difference in the prevalence of substance use in EC drug treatment centres compared to the findings of the current study could be because of the older age of treatment-seeking individuals in other centres compared to our study setting. The EC treatment centre figures were also drawn from an outpatient sample who did not necessarily have any comorbid psychiatric disorder.

In this study, substance use was not significantly associated with ethnicity or with level of education. Previous studies have shown similar results,16 while others have shown that those with substance use, especially cannabis use, have poor academic progress.26 Unemployment was associated with a higher prevalence of substance use (p < 0.001) in this study. The impact of substance use on employment remains unclear with some studies showing negative impact,12,40 while others show a complete absence of impact.41,42

The limitations associated with retrospective chart reviews are well known. This study was limited because of non-standardisation of assessing doctors who might have had varied clinical experience (intern doctors compared to specialist psychiatrists). Data collection was dependent on proper documentation of clinical notes and, as a result, there were missing data that could not be recovered. Additional data on the frequency of use, amount used and age of onset of drug use were not available in this sample.

Conclusion

In keeping with national and international literature, this study showed a high prevalence of substance use in patients with FEP. The most commonly used substances were cannabis, alcohol and stimulants. The study findings highlight the need for mental health services in the EC to focus on dual diagnosis in order to address the challenge of substance abuse and its association with FEP. With the recent constitutional ruling on personal use of cannabis in South Africa, the high prevalence of use and its clinical correlates in association with first-episode psychosis requires further monitoring and evaluation to detect any changes in trends which may affect utilisation of services.43 Preventative strategies focusing on substance use disorder could also assist in addressing the growing burden of mental disorders in this region. Further prospective research is needed to confirm the higher prevalence of substance use reflected in this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Dr N. Mtshengu for assistance with data collection, Miss N. Njokweni for assistance with accessing patient clinical files and Dr Karis Moxley (Department of Psychiatry, Stellenbosch University) for assistance with critical review and language editing.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

Y.T. did the literature review, managed data (collected, analysed and interpreted) and provided the first draft. Z.Z. and S.v.W. supervised the research from initiation to manuscript development and critically revised the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding information

The lead investigator received a grant for the study from Discovery Foundation - Rural Fellowship Award in the individual category.

Data availability statement

Data are available on request from the authors.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

1.Archie S, Rush BR, Akhtar-Danesh N, et al. Substance use and abuse in first-episode psychosis: Prevalence before and after early intervention. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(6):1354-1363. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbm011 [ Links ]

2.Addington J, Addington D. Patterns, predictors and impact of substance use in early psychosis: A longitudinal study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115(4):304-309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00900.x [ Links ]

3.Barnett JH, Werners U, Secher SM, et al. Substance use in a population-based clinic sample of people with first-episode psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190(June):515-520. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024448 [ Links ]

4.Ouellet-Plamondon C, Abdel-Baki A. [Young urban adults suffering from psychosis: The importance of close team work]. Sante Ment Que. 2011;36(2):33-51. https://doi.org/10.7202/1008589ar [ Links ]

5.Mishra a, Sp O, Chapagain M, Tulachan P. Prevalence of substance use in first episode psychosis and its association with socio-demographic variants in Nepalese Patients. J Psychiatr Assoc Nepal. 2014;(1):16-22. https://doi.org/10.3126/jpan.v3i1.11347 [ Links ]

6.Wisdon JP, Manuel JI, Drake RE. Substance use disorder among people with first-episode psychosis: A systematic review of course and treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(9):1007-1012. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.62.9.1007.Substance [ Links ]

7.Wade D, Harrigan S, McGorry PD, Burgess PM, Whelan G. Impact of severity of substance use disorder on symptomatic and functional outcome in young individuals with first-episode psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(5);767-774. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v68n0517 [ Links ]

8.Turkington A, Mulholland CC, Rushe TM, et al. Impact of persistent substance misuse on 1-year outcome in first-episode psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):242-248. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.057471 [ Links ]

9.Lambert M, Conus P, Lubman DI, et al. The impact of substance use disorders on clinical outcome in 643 patients with first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112(2):1411-1418. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00554.x [ Links ]

10.Morgan C, Abdul-Al R, Lappin JM, et al. Clinical and social determinants of duration of untreated psychosis in the ÆSOP first-episode psychosis study. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189(November):446-452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.021303 [ Links ]

11.Dean K, Walsh E, Morgan C, et al. Aggressive behaviour at first contact with services: Findings from the AESOP First Episode Psychosis Study. Psychol Med. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706008920 [ Links ]

12.Bühler B, Hambrecht M, Löffler W, An Der Heiden W, Häfner H. Precipitation and determination of the onset and course of schizophrenia by substance abuse - A retrospective and prospective study of 232 population-based first illness episodes. Schizophr Res. 2002;54(3):243-251. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00249-3 [ Links ]

13.Archie S, Rush BR, Akhtar-Danesh N, et al. Substance use and abuse in first-episode psychosis: Prevalence before and after early intervention. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(6):1354-1363. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbm011 [ Links ]

14.Larsen TK, Melle I, Auestad B, et al. Substance abuse in first-episode non-affective psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2006;88(1-3):55-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2006.07.018 [ Links ]

15.Abdel-Baki A, Ouellet-Plamondon C, Salvat É, Grar K, Potvin S. Symptomatic and functional outcomes of substance use disorder persistence 2 years after admission to a first-episode psychosis program. Psychiatry Res. 2017;247(November 2016):113-119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.11.007 [ Links ]

16.Mazzoncini R, Donoghue K, Hart J, et al. Illicit substance use and its correlates in first episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(5):351-358. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01483.x [ Links ]

17.Green AI, Tohen MF, Hamer RM, et al. First episode schizophrenia-related psychosis and substance use disorders: Acute response to olanzapine and haloperidol. Schizophr Res. 2004;66(2-3):125-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2003.08.001 [ Links ]

18.Barnes TRE, Mutsatsa SH, Hutton SB, Watt HC, Joyce EM. Comorbid substance use and age at onset of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188(3):237-242. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007237 [ Links ]

19.Herman AA, Stein DJ, Seedat S, Heeringa SG, Moomal H, Williams DR. The South African Stress and Health (SASH) study: 12-month and lifetime prevalence of common mental disorders. S Afr Med J. 2009;99(5):339-344. [ Links ]

20.Health SAD of, Council MR, OrcMacro. South Africa demographic and health survey 2003. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2007. [ Links ]

21.Wechsberg WM, Luseno WK, Karg RS, et al. Alcohol, cannabis, and methamphetamine use and other risk behaviours among Black and Coloured South African women: A small randomized trial in the Western Cape. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19(2):130-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.018 [ Links ]

22.Van Heerden MS, Grimsrud AT, Seedat S, Myer L, Williams DR, Stein DJ. Patterns of substance use in South Africa: Results from the South African Stress and Health study. S Afr Med J. 2009;99(5 Pt 2):358-366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.08.021.Secreted [ Links ]

23.Dada S, Burnhams NH, Laubscher R, Parry C, Myers B. Alcohol and other drug use among women seeking substance abuse treatment in the Western Cape, South Africa. S Afr J Sci. 2018;114(9-10):1-7. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2018/4451 [ Links ]

24.Weich L, Pienaar W. Occurrence of comorbid substance use disorders among acute psychiatric inpatients at Stikland Hospital in the Western Cape, South Africa. Afr J Psychiatry. 2009;12(3):213-217. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajpsy.v12i3.48496 [ Links ]

25.Paruk S, Ramlall S, Burns JK. Adolescent onset psychosis: A 2-year retrospective study of adolescents admitted to a general psychiatric unit. S Afr J Psychiatry. 2017;15(4):7. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v15i4.203 [ Links ]

26.Lachman A, Nassen R, Hawkridge S, Emsley RA. A retrospective chart review of the clinical and psychosocial profile of psychotic adolescents with comorbid substance use disorders presenting to acute adolescent psychiatric services at Tygerberg Hospital. S Afr J Psychiatry. 2012. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v18i2.351 [ Links ]

27.Davis GP, Tomita A, Baumgartner JN, et al. Substance use and duration of untreated psychosis in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. S Afr J Psychiatry. 2016;22(1):7. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v22i1.852 [ Links ]

28.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). 5th ed. Arlington, VA: AMA; 2013. [ Links ]

29.Provincial profile: Eastern Cape Community Survey 2016 [homepage on the Internet]. [13 April 2019] Report number 03-01-08. ISBN: 978-0-621-44980-8. Statistics South Africa; p. 155. Available from: www.statssa.gov.za. [ Links ]

30.Van Mastrigt S, Addington J, Addington D. Substance misuse at presentation to an early psychosis program. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(1):69-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-004-0713-0 [ Links ]

31.Sara GE, Large MM, Matheson SL, et al. Stimulant use disorders in people with psychosis: A meta-analysis of rate and factors affecting variation. Aust N Z J Psychiatr. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867414561526 [ Links ]

32.Mauri MC, Volonteri LS, De Gaspari IF, Colasanti A, Brambilla MA, Cerruti L. Substance abuse in first-episode schizophrenic patients: A retrospective study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2(4). https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-0179-2-4 [ Links ]

33.Akvardar Y, Tumuklu M, Akdede BB, Ulas H, Kitis A, Alptekin K. Substance use among patients with schizophrenia in a university hospital. Bull Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;14(4):191-197. [ Links ]

34.Dubertret C, Bidard I, Adès J, Gorwood P. Lifetime positive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia and cannabis abuse are partially explained by comorbid addiction. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):284-290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.006 [ Links ]

35.Sevy S, Robinson DG, Holloway S, et al. Correlates of substance misuse in patients with first-episode schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104(5):367-374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2001.00452.x [ Links ]

36.Rabinowitz J, Bromet EJ, Lavelle J, Carlson G, Kovasznay B, Schwartz JE. Prevalence and severity of substance use disorders and onset of psychosis in first-admission psychotic patients. Psychol Med. 1998;28(6):1411-1419. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291798007399 [ Links ]

37.Arranz B, Safont G, Corripio I, et al. Substance use in patients with first-episode psychosis: Is gender relevant? J Dual Diagn. 2015;11(3-4):153-160. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2015.1113761 [ Links ]

38.Lange EH, Nesvåg R, Ringen PA, et al. One year follow-up of alcohol and illicit substance use in first-episode psychosis: Does gender matter? Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(2):274-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.08.018 [ Links ]

39.Dada S, Burnhams NH, Erasmus J. Research brief: Monitoring alcohol, tobacco and other drug use trends in South Africa (July 1996-June 2017). 2017;20(June):1-24. [ Links ]

40.González-Pinto A, Alberich S, Barbeito S, et al. Cannabis and first-episode psychosis: Different long-term outcomes depending on continued or discontinued use. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):631-639. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp126 [ Links ]

41.Menezes NM, Malla AM, Norman RM, Archie S, Roy P, Zipursky RB. A multi-site Canadian perspective: Examining the functional outcome from first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120(2):138-146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01346.x [ Links ]

42.Sorbara F, Liraud F, Assens F, Abalan F, Verdoux H. Substance use and the course of early psychosis: A 2-year follow-up of first-admitted subjects. Eur Psychiatry. 2003;18(3):133-136. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(03)00027-0 [ Links ]

43.Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development and Others v Prince (Clarke and Others Intervening); National Director of Public Prosecutions and Others v Rubin; National Director of Public Prosecutions and Others v Acton (CCT 108/17) [2018] ZACC 30. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Yanga Thungana

thungana@aol.com

Received: 04 Jan. 2019

Accepted: 21 Aug. 2019

Published: 24 Oct. 2019