Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Psychiatry

versión On-line ISSN 2078-6786

versión impresa ISSN 1608-9685

S. Afr. j. psyc. vol.25 no.1 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v25i0.1392

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Barriers to care among people with schizophrenia attending a tertiary psychiatric hospital in Nigeria

Bawo O. JamesI; Felicia I. ThomasII; Omonefe J. Seb-AkahomenI; Nosa G. IgbinomwanhiaI; Chinwe F. InogboI; Graham ThornicroftIII

IDepartment of Clinical Services, Federal Neuro- Psychiatric Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria

IISynapse Centre for Psychological Medicine, Lagos, Nigeria

IIICentre for Global Mental Health, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neurosciences, Kings College London, England, United Kingdom

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Individuals with schizophrenia in low- and middle-income countries and their caregivers face multiple barriers to care-seeking and continuous engagement with treatment services. Identifying specific barrier patterns would aid targeted interventions aimed at improving treatment access.

AIM: The aim of this study was to determine stigma- and non-stigma-related barriers to care-seeking among persons with schizophrenia in Nigeria.

SETTING: This study was conducted at the Outpatient Clinics of the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria.

METHODS: A cross-sectional study of a dyad of persons with schizophrenia and caregivers (n = 161) attending outpatient services at a neuro-psychiatric hospital in Nigeria. Stigma- and non-stigma-related barriers were assessed using the 30-item Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation (BACE) scale.

RESULTS: Lack of insight, preference for alternative care, illness severity and financial constraints were common barriers to care-seeking among persons with schizophrenia. Females were significantly more likely to report greater overall treatment barrier (p < 0.01) and stigma-related barriers (p < 0.02).

CONCLUSION: This study shows that attitudinal barriers impede care access and engagement among persons with schizophrenia in Nigeria.

Keywords: barriers to care; schizophrenia; stigma; Nigeria; attitudes.

Background

Over 21 million people globally live with schizophrenia, a disabling mental disorder, affecting approximately 4-5 million individuals living in African countries.1 In Nigeria, pathways to care for mental disorders are complex and significantly influenced by stigma, poor understanding about these illnesses, cultural and religious factors, financial constraints, and poor integration of mental healthcare into primary healthcare systems.2,3 Therefore, only a minority of persons with mental illness access appropriate care in a timely manner. Furthermore, constant engagement with appropriate mental healthcare is low, even in tertiary hospital settings that provide the highest level of clinical expertise.4,5

Although some research has been conducted on pathways to care for mental disorders in Nigeria,6,7 there is a lack of evidence for the specific barriers (from the perspective of patients with schizophrenia and their caregivers) that prevent or discourage them from accessing mental health services or continuing with services after initial engagement. In the United Kingdom, stigma-related barriers (relating to employability and parenting roles) were major barriers in a cohort receiving care for mental health disorders. Professionals in mental healthcare also constitute a barrier to care albeit inadvertently. In addition, in developing countries, income-related disparities also serve as major non-stigma barriers to healthcare access.8,9,10

The aim of this study was to determine the barriers to access to mental healthcare among patients with schizophrenia and their caregivers attending a tertiary mental healthcare service in southern Nigeria. We specifically sought to identify barriers to mental healthcare for patients with schizophrenia and their caregivers and explore socio-demographic correlates.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study.

Study location

This study was conducted at the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital, Benin City. This is a tertiary healthcare facility funded by the Federal Government of Nigeria, which provides inpatient and outpatient mental health services, and community extension services.

Study participants

The study participants were adult patients aged 18-64 years with a diagnosis of schizophrenia who had been attending the outpatient clinics for at least 6 months. Secondly, caregivers of adult patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia who had been attending the outpatient clinic for at least 3 months were also interviewed. We excluded dyads who declined consent to participate in the study, patients who could not take a decision to participate in the study or were too ill to be interviewed.

Operational definition of 'caregiver'

For the purpose of this study, a caregiver was defined as a first-degree relative and a non-professional, non-paid person who was mostly involved with the everyday care of a patient. He or she would also be most likely to respond to any request for special assistance at any time, by the patient.11

Sample size

The participants consisted of consecutive sample of 161 patients and 161 caregivers who met the criteria for inclusion in the study, attending the hospital between April and September 2018.

Study instruments

•A semi-structured questionnaire designed by the researchers included information about gender, age, religion, level of formal education, duration of illness, duration of treatment and beliefs about aetiology of schizophrenia.

•The Barriers to Care Evaluation (BACE) version 4: This scale was developed and validated at the Health Services and Population Research Department, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, to assess barriers to mental healthcare for people with mental health problems. Its psychometric properties have been established and it has good reliability and validity.9 It is a 30-item scale that can be self-administered or interviewer-administered. The response to each question is rated on a Likert scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (a lot), with higher scores indicating greater barrier. The overall BACE score (mean of rating for all applicable items) may be used. Three different scores may be given for each barrier:

■ mean of the response scores

■ percentage reporting having experienced the barrier to any degree

■ percentage that rated the barrier as a major barrier (rating of 3).

The BACE treatment stigma subscale score is the mean of stigma-related items (3, 5, 8, 9, 12, 14, 17, 19, 21, 24, 26 and 28). In a similar way, subscale scores for instrumental barriers (items 1, 6, 11, 15, 16, 27, 29 and 30) and attitudinal barriers (items 2, 4, 7, 10, 13, 18, 20, 22, 23 and 25) may be calculated.

Procedure

All the interviewers (three psychiatrists) attended a start-up meeting, during which they were guided on how to complete the BACE questionnaire. The participants were interviewed in the private consulting rooms of the outpatient clinic. The interviews went thus: the semi-structured questionnaire was administered to the caregivers and to the patients, while the BACE questionnaire was administered to the patients alone (although with the caregivers in attendance). The case files of all the patients who participated in the study were tagged to prevent interviewing the same patient more than once.

Data analysis

Data were summarised using means and standard deviations, and displayed in tables. Reliability of the overall and stigma subscale of the BACE was determined using the Cronbach's alpha. The association between continuous variables was determined using t-test. Level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Study protocol was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital, Benin City. Participants were informed about the nature and aim of the study, and verbal informed consent was obtained. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained. Participants were also informed that they were free to opt out of the study at any time if they so desired, with no negative consequences as regards their treatment.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of patients and caregivers

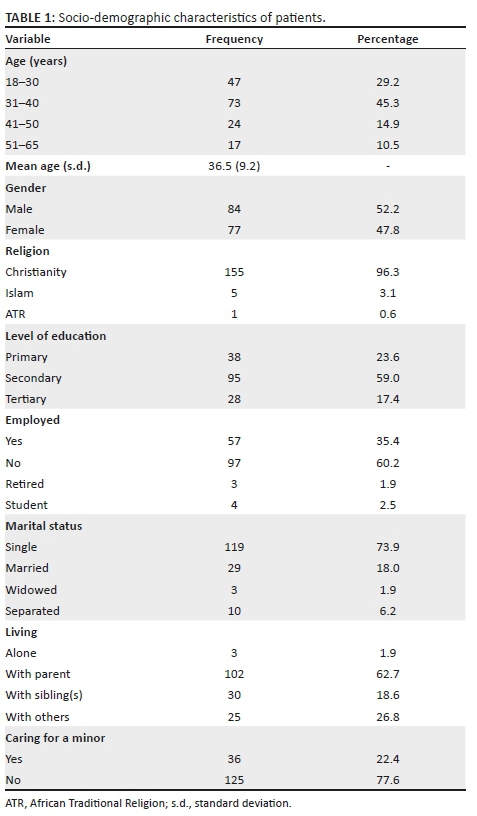

The average age (standard deviartion [s.d.]) of patients in this sample was 36.5 (9.2) years, with most in the 31-40 years' age range.

There were slightly more males (n = 84; 52.2%) and most were Christian (n = 155; 96.3%). Over half had a secondary level of education (n = 95; 59.0%). A majority were single (n = 119; 73.9%), unemployed (n = 97; 60.2%) and living with a family member (n = 132; 81.3%) and not caring for a minor (n = 125; 77.6%) (see Table 1).

Average caregiver age was 52.8 (13.3) years, and most were female (n = 112; 69.6%). A majority were Christians (n = 153; 95%) and employed (n = 122; 75.8%). Slightly under half of caregivers rated their 'ease of bringing their relatives to hospital' as 'difficult/very difficult' (n = 77; 47.9%). Over half of caregivers were parents (n = 85; 52.8%), as shown in Table 2.

Barriers to care

The reliability of the overall BACE scale was 0.80, while that of the 12-item treatment stigma subscale was 0.87. The stigma-related barriers most commonly endorsed (identified as a major barrier) were 'feeling embarrassed or ashamed' (n = 20; 12.4%), 'concern that I might be seen as crazy' (n = 15; 9.3%) and 'concern about what my friends might think, say or do' (n = 12; 7.5%) (see Table 3).

Table 4 shows that common attitudinal barriers endorsed were 'thinking that I do not have a problem' (n = 60; 37.3%), 'preferring to get alternative forms of care' (n = 33; 20.5%) and 'wanting to solve the problem on my own' (n = 23, 14.3%).

Findings highlighted in Table 5 reveal that instrumental barriers commonly endorsed were 'being too unwell to ask for help' (n = 38; 23.6%), 'problems with transport or travelling to appointments' (n = 30; 18.6%) and 'financial constraints and unsure where to get professional help' (n = 28, 17.4%).

Gender differences

There were differences in reported barriers across gender. Female patients were significantly more likely to report barriers overall compared with males (19.91 [11.30] vs. 15.92 [7.55], t = 2.70, p < 0.01). A similar pattern was observed in the stigma subscale (6.65 [6.87] vs. 4.43 [4.97], t = 2.36, p < 0.02). No significant differences were seen when instrumental barriers (p = 0.24) and attitudinal barriers (p = 0.05) were compared.

Discussion

This study showed that barriers to care are still common among persons with schizophrenia receiving care in a low- and middle-income country. Specifically, a lack of insight into the illness continues to hamper constant engagement with available treatment services. The ignorance about the illness and its course is further amplified when participants endorsed seeking alternative forms of care as a barrier to effective treatment. Consequently, we infer that these attitudinal barriers may have resulted in prolonged duration of untreated psychosis. Expectedly, financial difficulties and problems with transport logistics were also identified as major instrumental barriers. In Nigeria, payment for mental healthcare is largely borne by patients or their family members, with a minority having access to limited health insurance. We also report that stigma as a barrier to care had a higher deleterious effect on female patients compared with males.

The validation study of the BACE conducted among service users in the United Kingdom9 identified that stigma-related barriers were major barriers, whereas attitudinal barriers were dominant in the Nigerian sample. A study utilising the BACE to ascertain health-seeking prospects of young adults in the United Kingdom saw a marginal preponderance of attitudinal barriers compared with stigma-related barriers.12 Although earlier reports from Nigeria identify that self-stigma is common among the mentally ill,13,14 it seems that its influence as a treatment or care barrier is mediated by the role of caregivers in treatment-seeking. Thus, a dynamic interaction exists between the individuals recognising symptoms as those of a mental illness, recognising the need for treatment and seeking the support of caregivers to access or pay for care.

The finding that lack of insight was a major barrier to seeking care is consistent with beliefs about the aetiology of mental illness. Individuals in Nigeria are more likely to endorse spiritual or magico-religious aetiologies or the role of psychoactive drugs and therefore seek alternative care options that are consistent with their belief systems as regards the aetiology of their symptoms.15-17 Often, it is the failure of alternative and complementary systems of care that presents the individual or family members with no other choice than to present to orthodox care services. A recent review identified 'lack of knowledge and understanding' as one of the overarching themes that modify pathways to care for persons with mental illness.18

The increased likelihood of females reporting a barrier is consistent with a recent robust evaluation conducted in the United Kingdom.19 Females in low- and middle-income countries need to overcome cultural practices and attitudinal dispositions in society that reduce empowerment and access to available services. More commonly, symptom severity is greater in females before they can get the support from family to access care.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to report on barriers to care utilising the BACE in a low- and middle-income country. Another strength of the study was its ability to show that gender differences play a role in perceptions of the illness, seeking care and attitudes within a defined sub-culture. We therefore postulate that the knowledge of gender differences in attitudes, illness perception and care-seeking would facilitate the design of interventions aimed at overcoming the barriers to seeking care in patients with schizophrenia. A possible limitation is the fact that participants were drawn from a single hospital setting; however, studies have shown that not much difference exists across the country as regards the belief systems about mental illness, early presentation and seeking alternative treatment options.20,21 In addition, the BACE was interviewer-administered, so that problems with literacy and comprehension could be overcome. Also, we noted that the percentage of patients reporting items on the BACE as a major barrier seems low, while percentages reporting items to some degree are fairly high. This might possibly be a limitation of this study that may be accounted for by interviewer bias. Furthermore, the fact that a caregiver had to form part of the study might in itself be seen as an instrumental barrier to care, as some patients may require constant guidance from caregivers, hence the need to accompany them to the hospital for treatment.

Implications for future research and practice

We note that even among individuals already receiving care in mental health services, the level of stigma- and non-stigma-related barriers is high. It is essential therefore to determine how stigma-related factors impede care access among persons at risk, or with mental health problems but yet to access available services. Secondly, research on interventions that reduce stigma as well as incentives that improve treatment access, particularly among the economically disadvantaged, are needed. There is evidence that the poor usually have a poorer uptake of available and effective treatment services.

Lastly, mental health professionals need to be aware that stigma may still impede treatment engagement even among those who routinely access care. Providing information, identifying and eliminating systematic practices or behaviours that promote stigma will benefit barrier elimination.

Conclusion

Persons with schizophrenia receiving tertiary level care in Nigeria report several stigma- and non-stigma related barriers to care. Specifically, a lack of insight, a preference for alternative care, greater illness severity and a lack of money to pay for care were commonly endorsed by participants. These barriers were more prevalent among persons with schizophrenia who were female.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Authors' contributions

B.O.J., F.I.T., O.J.S.-A., N.G.I., C.F.I. and G.T. were involved in the study design. B.O.J., N.G.I., O.J.S.-A. and F.I.T. collected the data. B.O.J. analysed the data. All authors contributed to the writing of the article and accepted the final draft.

Funding

No grants, equipment or drugs or other support was used in the conduct of this work or the writing of the article.

Data availability statement

Data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

1.Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e141. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020141 [ Links ]

2.Ikwuka U, Galbraith N, Nyatanga L. Causal attribution of mental illness in South-Eastern Nigeria. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;60(3):274-279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764013485331 [ Links ]

3.Igbinomwanhia NG, James BO, Omoaregba JO. The attitudes of clergy in Benin City, Nigeria towards persons with mental illness. Afr J Psychiatry. 2013;16(3):196-200. http://doi.org/10.4314/ajpsy.v16i3.26 [ Links ]

4.Thomas FI, Olotu SO, Omoaregba JO. Prevalence, factors and reasons associated with missed first appointments among out-patients with schizophrenia at the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital, Benin City. BJPsych Open. 2018;4(2):49-54. http://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2017.11 [ Links ]

5.Akhigbe S, Morakinyo O, Lawani A, James B, Omoaregba J. Prevalence and Correlates of Missed First Appointments among Outpatients at a Psychiatric Hospital in Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4(5):763-768. http://doi.org/10.4103/2141-9248.141550 [ Links ]

6.Abiodun OA. Pathways to mental health care in Nigeria. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46(8):823-826. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.46.8.823 [ Links ]

7.Gureje O, Acha R, Odejide A. Pathways to psychiatric care in Ibadan, Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med. 1995;3(47):125-129. [ Links ]

8.Knaak S, Mantler E, Szeto A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: Barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthc Manag Forum. 2017;30(2):111-116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0840470416679413 [ Links ]

9.Clement S, Brohan E, Jeffery D, Henderson C, Hatch SL, Thornicroft G. Development and psychometric properties the Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation scale (BACE) related to people with mental ill health. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-36 [ Links ]

10.O'Donnell O. Access to health care in developing countries: Breaking down demand side barriers. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(12):2820-2834. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-311x2007001200003 [ Links ]

11.Lasebikan V, Ayinde O. Family burden in caregivers of schizophrenia patients: Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35(1):60. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.112205 [ Links ]

12.Salaheddin K, Mason B. Identifying barriers to mental health help-seeking among young adults in the UK: A cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(651):e686-e692. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X687313 [ Links ]

13.Adewuya A, Erinfolami A, Erinfolami A, Ola B. Correlates of self-stigma among outpatients with mental illness in Lagos Nigeria. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57(4):418-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764010363522 [ Links ]

14.Mosanya TJ, Adelufosi AO, Adebowale OT, Ogunwale A, Adebayo OK. Self-stigma, quality of life and schizophrenia: An outpatient clinic survey in Nigeria. Int J Soc Psychiatry [serial online]. 2013 [cited 2014 Dec 10];60(4):377-86. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23828766. [ Links ]

15.Gureje O, Nortje G, Makanjuola V, Oladeji BD, Seedat S, Jenkins R. The role of global traditional and complementary systems of medicine in the treatment of mental health disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(2):168-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00013-9 [ Links ]

16.Igberase O, Okogbenin E. Beliefs about the cause of schizophrenia among caregivers in Midwestern Nigeria. Ment Illn. 2017;9(1):6983. https://doi.org/10.4081/mi.2017.6983 [ Links ]

17.Lasebikan VO. Cultural aspects of mental health and mental health service delivery with a focus on Nigeria within a global community. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2016;19(4):323-338. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2016.1180672 [ Links ]

18.Gronholm PC, Thornicroft G, Laurens KR, Evans-Lacko S. Mental health-related stigma and pathways to care for people at risk of psychotic disorders or experiencing first-episode psychosis: A systematic review. Psychol Med. 2017;47(11):1867-1879. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717000344 [ Links ]

19.Dockery L, Jeffery D, Schauman O, et al. Stigma- and non-stigma-related treatment barriers to mental healthcare reported by service users and caregivers. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228(3):612-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.044 [ Links ]

20.Armiyau AY. A review of stigma and mental illness in Nigeria. J Clin Case Reports. 2015;5(1):488. https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7920.1000488 [ Links ]

21.Okpalauwaekwe U, Mela M, Oji C. Knowledge of and Attitude to Mental Illnesses in Nigeria: A Scoping Review. Integr J Glob Heal. 2017;1(1). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Bawo James

bawojames@yahoo.com

Received: 15 Mar. 2019

Accepted: 21 Aug. 2019

Published: 21 Oct. 2019